RAILROAD BILL

RAILROAD BILL RAILROAD BILL

RAILROAD BILL(?–7 Mar. 1896), thief and folk hero, was the nickname of a man of such obscure origins that his real name is in question. Most writers have believed him to be Morris Slater, but a rival candidate for the honor is an equally obscure man named Bill McCoy. But in song and story, where he has long had a place, the question is of small interest and Railroad Bill is name enough. A ballad regaling his exploits began circulating among field hands, turpentine camp workers, prisoners, and other groups from the black underclass of the deep South, several years before it first found its way into print in 1911. A version of this blues ballad was first recorded in 1924 by Gid Tanner and Riley Puckett, and THOMAS A. DORSEY, who sang blues under the name Railroad Bill. The ballad got a second wind during the folk music vogue of the 1950s and 1960s, and in 1981 the musical play Railroad Bill by C. R. Portz was produced for the Labor Theater in New York City. It subsequently toured thirty-five cities.

The name Railroad Bill, or often simply “Railroad,” was given to him by trainmen and derived from his penchant for riding the cars as an anonymous nonpaying passenger of the Louisville and Nashville Railroad (L&N). Thus he might appear to be no more than a common tramp or hobo, as the large floating population of migratory workers who more or less surreptitiously rode the cars of all the nation’s railroads were labeled. But Railroad Bill limited his riding to two adjoining South Alabama counties, Escambia and Baldwin. Sometime in the winter of 1895 he began to be noticed by trainmen often enough that he soon acquired some notoriety and a nickname. It did not make him less worthy of remark that he was always armed, with a rifle and one or more pistols. He was, as it turned out, quite prepared to offer resistance to the rough treatment normally meted out to tramps.

An attitude of armed resistance from a black man was bound inevitably to bring him into conflict with the civil authorities, who were in any case inclined to be solicitous of the L&N, the dominant economic power in South Alabama. The conflict began on 6 March 1895, only a month or two after trainmen first became aware of Railroad Bill. L&N employees discovered him asleep on the platform of a water tank in Baldwin County, on the Flomaton to Mobile run, and tried to take him into custody. He drove them off with gunfire and forced them to take shelter in a nearby shack. When a freight train pulled up to take on water he hijacked it and, after firing additional rounds into the shack, forced the engineer to take him farther up the road, whereupon he left the train and disappeared into the woods. After that, pursuit of Railroad Bill was relentless. A month to the day later he was cornered at Bay Minette by a posse led by a railroad detective. A deputy, James H. Stewart, was killed in the ensuing gunfight, but once again the fugitive slipped away. The railroad provided a “special” to transport Sheriff E. S. McMillan from Brewton, the county seat of Escambia, to the scene with a pack of bloodhounds, but a heavy rainfall washed away the scent.

In mid-April a reward was posted by the L&N and the state of Alabama totaling five hundred dollars. The lure of this reward and a rumored sighting of the fugitive led Sheriff McMillan out of his jurisdiction to Bluff Springs, Florida, where he found Railroad Bill and met with death at his hands. The reward climbed to $1,250, and the manhunt intensified. A small army with packs of dogs picked up his scent near Brewton in August, but he dove into Murder Swamp near Castelberry and disappeared. During this period, from March to August, the legend of Railroad Bill took shape among poor blacks in the region. He was viewed as a “conjure man,” one who could change his shape and slip away from pursuers. He was clever and outwitted his enemies; he was a trickster who laid traps for the trapper and a fighter who refused to bend his neck and submit to the oppressor. He demanded respect, and in time some whites grudgingly gave it: Brewton’s Pine Belt News reported after Railroad Bill’s escape into Murder Swamp that he had “outwitted and outgeneraled at least one hundred men armed to the teeth.” During this period a Robin Hood-style Railroad Bill emerged, who, it was said, stole canned goods from boxcars and distributed them to poor illiterate blacks like himself. Carl Carmer, a white writer in the 1930s, claimed that Railroad Bill forced poor blacks at gunpoint to buy the goods from him, but Carmer never explained how it was possible to get money out of people who rarely if ever saw any. Railroad Bill staved off death and capture for an entire year, a virtual impossibility had he not had supporters among the poor black population of the region.

Sightings became infrequent after Murder Swamp, and some concluded Railroad Bill had left the area. The “wanted” poster with its reward was more widely circulated. The result was something like open season on vagrant blacks in the lower South. The Montgomery Advertiser reported that “several were shot in Florida, Georgia, Mississippi and even in Texas,” adding with unconscious grisly humor, “only one was brought here to be identified.” That one arrived at Union Station in a pine box in August, escorted by the two men from Chipley, Florida, who had shot him in hopes of collecting the reward. Doubts about whether he remained in the area were answered on 7 March 1896, exactly a year and a day after the affair at the water tower when determined pursuit began. Railroad Bill was shot without warning, from ambush, by a private citizen seeking the reward, which by now included a lifetime pass on the L&N Railroad. Bill had been sitting on a barrel eating cheese and crackers in a small Atmore, Alabama, grocery. Perhaps he was tired as well as hungry.

Railroad Bill’s real name probably will never be known. At the time of the water tower incident and up to the killing of Deputy Stewart he had only the nickname, but in mid-April the first “wanted” posters went up in Mobile identifying Railroad Bill as Morris Slater, who, though the notice did not state it, had been a worker in a turpentine camp near Bluff Springs, Florida. These camps were often little more than penal colonies. They employed convict labor and were heavily into debt peonage. People were not supposed to leave, but Slater did, after killing the marshal of Bluff Springs. When railroad detectives stumbled on this story their interest was primarily in Slater’s nickname. He had been called “Railroad Time,” and “Railroad” for short, because of his quick efficient work. The detectives quickly concluded, because of the similarities in nicknames, that Slater was their man. The problem, of course, is that the trainmen called their rider Railroad Bill precisely because they had no idea who he was and well before railroad authorities heard about Slater. If the detectives were right, then it follows that the same man independently won strangely similar nicknames in two different settings, once because he was a good worker, and again because he was a freeloader.

No one from the turpentine camp who had known Slater identified the body, but neither the railroad detectives nor the civil authorities involved questioned the identification. The body was taken to Brewton, on its way to Montgomery, where it would go on display for the public’s gratification, but it was also displayed for a time in Brewton and recognized. The Pine Belt News reported that residents recognized the body as that of Bill McCoy, a man who would have been about forty, the approximate age of the corpse, since he had been brought to the area from Coldwater, Florida, as a young man eighteen years earlier. McCoy was remembered as a town troublemaker who two years earlier had threatened T. R. Miller, the richest man in town, when he worked in Miller’s sawmill and lumberyard. He had fled the scene hastily, not to be seen again until his corpse went on display as Railroad Bill. But, apart from the local newspaper stories, no one disputed the Slater identification, and the local Brewton people seem to have concluded that Morris Slater must have been a name used by Bill McCoy after he fled the town. The problem with that conclusion is that when the incident at Miller’s sawmill occurred Morris Slater had already earned the nickname “Railroad Time” in a Florida turpentine camp.

The Brewton newspapers Pine Belt News and Standard Gauge are the best places to follow the story of Railroad Bill.

Penick, James L. “Railroad Bill.” Gulf Coast Historical Review 10 (1994): 85–92.

Wright, A. J., comp. Criminal Activity in the Deep South, 1700–1933 (1989).

—JAMES L. PENICK

RAINES, FRANKLIN DELANO

RAINES, FRANKLIN DELANO(14 Jan. 1949–), corporate executive and government official, was born Franklin Delano Raines in Seattle, Washington, the fourth of seven children of Delno Thomas Raines, a custodian, and Ida Mae Raines, a cleaning woman. He was named after his uncle Frank and his father, but the hospital misspelled his middle name as “Delano.”

The Raines family eventually moved into a house that Delno Raines had built himself over the course of five years. The household was constantly fighting economic challenges. When Raines was a young boy, his father was hospitalized for an illness and lost his job. As a result, the family received welfare for two years. Eventually, Delno Raines got full-time work as a custodian for the city of Seattle. Ida Raines added to their income by working as a cleaning woman for the aircraft company Boeing. But Raines would always remember the lessons of being on the brink of financial ruin. He later recalled that the experience of living with nothing to fall back on made him “quite sensitive to issues of personal and financial security. That probably made me very conservative in my own financial dealings and also made me worry a lot about people” (Stevenson, New York Times, 17 May 1998).

Very early in his life it was clear that Raines was an achiever and destined for great things. When he was in high school, the Seattle Times called him “Mr. Everything” (Karen Tumulty, Time, 10 Feb. 1997). He was state debate champion, captain of the high school football team, and student president of his high school. His academic excellence (reflected in his 4.0 average) earned Raines a four-year scholarship to Harvard University, which he entered in 1967. He worked toward a BA in Government and impressed many, including Professor Daniel Patrick Moynihan, the future U.S. senator. In 1969 Raines was asked to intern at the White House in the Urban Affairs Department headed by Moynihan. At age twenty Raines was making a presentation to President Nixon.

After graduating in 1971 Raines went to Magdalen College at the University of Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar. After that, in 1974, he entered Harvard Law School, from which he graduated cum laude in 1976. After a seven-month stint at the law firm Preston, Gates, and Ellis, Raines’s impressive résumé earned him a position as assistant director for economics and government in the Office of Management and Budget in President Jimmy Carter’s administration. This was the beginning of a career that would marry his political savvy and his financial acumen. In 1979 he moved to Wall Street and became an investment banker for the prestigious firm Lazard Frères.

Raines worked in the municipal finance department and advised cities and states about their finances and ability to raise money for government projects, such as bridges and buildings. The political skills that he had developed over his career continued to help him in his new position. Raines landed accounts with major cities like Washington, D.C., Chicago, and Detroit. He also worked on statewide accounts for Texas and Iowa, among others. With his help these municipalities, many of which were in dire financial trouble, were able to strengthen their finances. The most dramatic example of his work came in Washington, D.C. He helped reorganize the city’s finances with such success that Wall Street allowed Washington to borrow money for the first time in a century.

Raines’s success was rewarded in 1985 when he was named a partner at Lazard Frères. This appointment had broader implications. He had already been one of a handful of African Americans investment bankers in the clubby world of Wall Street. Now he was the first African American partner at a major investment bank. Raines once reflected about the importance of his achievement in the securities industry by saying, “I felt it was significant because for years, people would be wowed by the fact that you were black and a vice president. Now partner or managing director became the new standard” (Bell, 143).

During this period things were also blossoming in Raines’ personal life. He married Wendy Farrow in 1982, and the couple went on to have three daughters. His commitment to his family persuaded Raines to make a career-altering decision. In 1991, after twelve years of working in municipal finance, he decided to leave Lazard. Tired of the extensive traveling that was necessary in his work with municipalities around the country, a workload that had him on a plane as many as five days a week, he decided that he would quit his lucrative career on Wall Street to spend more time with his family.

Raines, with his impeccable reputation, was not out of work for long. Later that year he was asked to join Fannie Mae, a huge mortgage corporation located only minutes from his house. Fannie Mae, formerly known as the Federal National Mortgage Association, was created in 1938 as a government agency. In the 1960s it was turned into a corporation owned by shareholders. It purchases mortgages from lending institutions and resells them to the secondary market. As vice chairman, Raines had the main responsibility to improve Fannie Mae’s technology. He was also in charge of the firm’s credit policy and legal issues, along with sundry other functions.

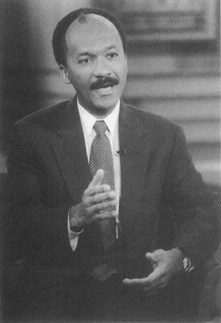

Franklin Raines on Fox TV in April 1998. Getty Images

Raines continued in this position until 1996, when President Bill Clinton called to ask him to head the Office of Management and Budget. He reentered public service and led the country to its first balanced budget since 1969. After years of success in this position, Fannie Mae came calling again, and in January 1999 Raines made history. He became the first African American to lead a Fortune 500 company, and soon other black executives like STANLEY O’NEAL, RICHARD DEAN PARSONS, and KENNETH CHENAULT would also head major corporations.

Fannie Mae is the largest source of private financing for home mortgages. One of Raines’s primary objectives was to increase his company’s business by spurring more home ownership in the minority community. It is an issue close to his heart, because his father could not get a mortgage loan until the house he was building was almost finished. The company itself also is concentrating on creating a talented and diverse workforce. In 2002 Fortune ranked Fannie Mae number one on their “50 Best Companies for Minorities” list (Jonathan Hickman, Fortune, 8 July 2002).

Frank Raines has come a long way from his old neighborhood in Seattle. He has conquered prestigious universities, Wall Street, and government and now heads one of the biggest corporations in the world. In addition to his responsibilities to his shareholders and employees, he also recognizes the responsibility of being a “first.” As he once said, “It’s part of my job to insure that the path I’ve been able to follow can be followed by other black kids. There are a lot of shoulders I get to stand on. I need to provide a hand and shoulders for others to follow” (Stevenson, New York Times, 17 May 1998).

Bell, Gregory S. In the Black: A History of African Americans on Wall Street (2001).

Cose, Ellis. The Envy of the World: On Being a Black Man in America (2002).

Stevenson, Richard W. “A Homecoming at Fannie Mae.” New York Times, 17 May 1998, BUI.

—GREGORY S. BELL

RAINEY, MA

RAINEY, MA(26 Apr. 1886–22 Dec. 1939), vaudeville artiste and “Mother of the Blues,” was born Gertrude Pridgett in Columbus, Georgia, the daughter of Ella Allen, an employee of the Georgia Central Railroad, and Thomas Pridgett, whose occupation is unknown. Around 1900, at the age of fourteen, Pridgett made her debut in the Bunch of Blackberries revue at the Springer Opera House in Columbus, one of the biggest theaters in Georgia and a venue that had been graced by, among others, Lillie Langtry and Oscar Wilde. Within two years she was a regular in minstrel tent shows—troupes of singers, acrobats, dancers, and novelty acts—which traveled throughout the South. At one show in Missouri in 1902 she heard a new musical form, “the blues,” and incorporated it into her act. Although she did not discover or name the blues, as legend would later have it, Gertrude Pridgett was undeniably one of the pioneers of the three-line stanza, twelve-bar style now known as the “classic blues.”

In 1904 the seventeen-year-old Gertrude married William Rainey, a comedian, dancer, and minstrel-show veteran. “Ma” and “Pa” Rainey soon became a fixture on the southern tent-show circuit, and they achieved their greatest success in 1914–1916 as Rainey and Rainey, Assassinators of the Blues, part of the touring Tolliver’s Circus and Musical Extravaganza. Their adopted son, Danny, “the world’s greatest juvenile stepper,” also worked with the show.

The summer tent shows took the Raineys throughout the South, where Ma was popular among both white and black audiences. Winters brought Ma, billed as Madame Gertrude Rainey, to New Orleans, where she performed with several pioneering jazz and blues musicians, including SIDNEY BECHET and KING OLIVER. Around 1914 Ma took a young blues singer from Chattanooga, Tennessee, BESSIE SMITH, under her wing—legend erroneously had it that she kidnapped her—and the two collaborated and remained friends over the next two decades. During these tent-show years, Ma honed a flamboyant stage persona, making her entrance in a bejeweled, floor-length gown and a necklace made of twenty-dollar gold pieces. The blues composer THOMAS A. DORSEY recalled that Ma had the audience in the palm of her hand even before she began to sing, while LANGSTON HUGHES noted that only a testifying Holiness church could match the enthusiasm of a Ma Rainey concert.

Rainey’s voice was earthy and powerful, a rural Georgian contralto with a distinctive moan and lisp. One blues singer also suggested that Ma held a dime under her tongue to prevent a stutter. Far from hindering her performance, these imperfections made Rainey’s vocal style even more appealing to an audience that shared her down-to-earth philosophy, captured in “Down in the Basement”:

Grand Opera and parlor junk

I’ll tell the world it’s all bunk

That’s the kind of stuff I shun

Let’s get dirty and have some fun.

Rainey often sang of pain and love lost or betrayed, but her songs—and her life—also celebrated the bawdy and unabashed pleasures of the flesh. Ma joked with her audiences that she preferred her men “young and tender” (Barlow, 159), but in songs such as “Lawd Send Me a Man Blues,” the preference matters less than the pleasure: “Send me a Zulu, a voodoo, any old man,/I’m not that particular, boys, I’ll take what I can.”

By World War I, Ma Rainey’s star had eclipsed that of Pa’s. (They separated in the late teens, and Pa died soon after.) In 1923 Rainey began a recording career with Chicago’s Paramount Records, which brought her down-home country blues to a national audience. Over the next five years, she recorded more than a hundred songs with many of the leading instrumentalists of the day, including Lovie Austin, Coleman Hawkins, and Thomas A. Dorsey, who also led Ma’s touring band. In 1924 a young LOUIS ARMSTRONG played cornet on her most famous release, “See See Rider.” Though already a blues standard, Ma’s rendition was the first and, bluesologists contend, the definitive recording of the song.

Her success as a recording artist and the general popularity of the “race records” industry led to a string of headlining tours with the Theater Owners Booking Association (TOBA). Black performers often called the organization “Tough on Black Asses,” because of its low wages and grueling schedule, but Rainey’s sense of fairness may have assuaged any complaints from the touring entourage of singers, dancers, and comedians. Unlike many TOBA head-liners, Ma never skipped town without paying her fellow performers. As a teenager, Lionel Hampton, who knew Ma through his bootlegger uncle in Chicago, “used to dream of joining Ma Rainey’s band because she treated her musicians so wonderfully and always bought them an instrument” (Lieb, 26). Rainey’s TOBA shows were even more popular than her tent shows had been, and her audience spread to midwest-em cities, whose black populations had swelled during the Great Migration. The shift from tents to theaters also provided new outlets for Ma’s showmanship. She now made an even grander entrance, stepping out of the doors of a huge Victrola onto the stage, wearing her trademark spangles and sequins.

Contemporaries often contrasted Ma’s evenhanded temperament with Bessie Smith’s hard-drinking, fiery temper, but Rainey was not unacquainted with the wrong side of the law. Ma’s love of jewelry once led to an arrest onstage in Cleveland, Ohio, when police from Nashville, Tennessee, arrested her for possession of stolen goods. Ma denied knowing that the items were hot, but was detained in Nashville for a week and forced to return the jewelry. More notoriously, Rainey spent a night in jail in Chicago in 1925, when neighbors called the police to complain about a loud and drunken party that she was holding with a group of women. When the police discovered the women in various states of undress, they arrested Ma for “running an indecent party.” Her friend Bessie Smith bailed her out the next day.

That incident and several biographies of Smith have highlighted Rainey’s open bisexuality and the possibility of a lesbian relationship between the two women. To be sure, Ma Rainey’s life and songs rejected the prevailing puritan orthodoxy when it came to sexuality. In “Sissy Blues,” written by Tom Dorsey, she bemoans the loss of her man to his male lover: “My man’s got a sissy, his name is Miss Kate, / He shook that thing like jelly on a plate.” Most famously, in “Prove It on Me Blues,” Rainey declares, “Went out last night with a crowd of my friends, / They must’ve been women, ‘cause I don’t like no men.” Ma’s bold assertion of her preference for women alternated with a coy, but knowing wink to the taboo of that choice: “’Cause they say I do it, ain’t nobody caught me,/Sure got to prove it on me.” Paramount’s advertisement for the record was somewhat less coy, depicting a hefty Ma Rainey in waistcoat, men’s jacket, shirt, tie, and fedora—though still wearing a skirt—towering over two slim, femininely dressed young women while a policeman looks on.

The sexual politics of the lyrics were just one aspect of the song, however. Paramount appeared just as keen to highlight that it was “recorded by the latest electric method,” all the better to hear Ma’s vocals and the “bang-up accompaniment by the Tub Jug Washboard Band.” Indeed, the company saw no problem in promoting some of its most popular gospel spirituals on the same advertisement. Like Ma Rainey herself, the race records industry of the 1920s may have been less squeamish about open declarations of homosexuality than many media giants in the late twentieth century.

Paramount ended Rainey’s recording contract in 1928, shortly after the release of “Prove It on Me Blues,” but not because of any controversy regarding the record itself. The company argued that Ma’s “down home material had gone out of fashion,” though that did not deter the label from signing male country blues performers who accepted lower fees. Ma returned to the southern tent-show circuit with TOBA, but by the early 1930s the Great Depression and the rival attractions of radio and the movies had destroyed the mass audience for the old-time country blues and black vaudeville at which Rainey excelled. Undeterred, though as much through necessity as choice, Ma returned to her southern roots, touring the oil-field towns of East Texas with the Donald MacGregor Carnival. Gone were the gold necklaces, the touring bus, and the grand entrance out of a huge Victrola. Now MacGregor, formerly the “Scottish Giant” in the Ringling Brothers’ circus, stood outside Ma’s tent and barked his introduction of the “Black Nightingale” inside. Rainey’s performances were as entertaining as ever, but the uncertainty and poor wages of the tent-show circuit may have somewhat diminished her trademark good humor and generosity. A young guitarist who toured with her in those years, Aaron “T-Bone” Walker, described Rainey as “mean as hell, but she sang nice blues and never cursed me out” (Lieb, 46–47).

The death of her sister Malissa in 1935 brought Ma Rainey back to Columbus to look after her mother. At some time before that Ma had separated from her second husband, whose name is not known. Although she no longer performed, Rainey opened two theaters in Rome, Georgia, where she died of heart disease in December 1939, aged fifty-three. The obituary in Ma’s local newspaper noted that she was a housekeeper but failed to mention her musical career. In the 1980s, however, both the Blues Foundation Hall of Fame and the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame recognized Ma Rainey’s significance as a consummate performer and as a pioneer of the classic blues.

Barlow, William. “Looking Up at Down”: The Emergence of Blues Culture (1989).

Carby, Hazel. “It Jus’ Be’s Dat Way Sometime: The Sexual Politics of Women’s Blues” in The Jazz Cadence of American Culture, ed. Robert G. O’Meally (1998).

Davis, Angela Y. Blues Legacies and Black Feminism: Gertrude “Ma” Rainey, Bessie Smith, and Billie Holiday (1998).

Lieb, Sandra. Mother of the Blues: A Study of Ma Rainey (1981).

Discography

Complete Recorded Works in Chronological Order, 1923–1927 (vols. 1–4, Document Records DOCD 5581–5584).

Complete Recorded Works: 1928 Sessions (Document Records DOCD 5156).

—STEVEN J. NIVEN

RANDOLPH, A. PHILIP

RANDOLPH, A. PHILIP(15 Apr. 1889–16 May 1979), labor organizer, editor, and activist, was born Asa Philip Randolph in Crescent City, Florida, to Elizabeth Robinson and James Randolph, an African Methodist Episcopal Church preacher. In 1891 the Randolphs moved to Jacksonville, where James had been offered the pastorship of a small church. Both Asa Philip and his older brother, James Jr., were talented students who graduated from Cookman Institute (later Bethune-Cookman College), the first high school for African Americans in Florida.

Randolph left Florida in 1911, moving to New York to pursue a career as an actor. Between 1912 and 1917 he attended City College, where he was first exposed to the ideas of Karl Marx and political radicalism. He joined the Socialist Party in 1916, attracted to the party’s economic analysis of black exploitation in America. Randolph, along with W. E. B. Du Bois, HUBERT HENRY HARRISON, and Chandler Owen, was one of the pioneer black members of the Socialist Party—then led by Eugene Debs. Like a number of his peers, Randolph did not subscribe to a belief in a “special” racialized oppression of blacks that existed independent of class. Rather, he argued at this point that socialism would essentially “answer” the “Negro question.” His faith in the socialist solution can be seen in the title of an essay he wrote on racial violence, “Lynching: Capitalism Its Cause; Socialism Its Cure” (Messenger, September 1921).

In 1916 Randolph and Owen began working to organize the black labor force, founding the short-lived United Brotherhood of Elevator and Switchboard Operators union. Shortly thereafter, they co-edited the Hotel Messenger, the journal of the Headwaiters and Sidewaiters Society. After being fired by the organization, they created The Messenger in 1917—with crucial financial support from Lucille Randolph, a beauty salon owner whom Randolph had married in 1914. The couple had no children. Lucille Randolph’s success as an entrepreneur was a consistent source of stability—despite the fact that her husband’s reputation as a radical scared away some of her clientele. Billing itself as “The Only Radical Negro Magazine,” the boldly iconoclastic Messenger quickly became one of the benchmark publications of the incipient “New Negro” movement. A single issue contained the views of Abram Harris, KELLY MILLER, GEORGE SCHUYLER, ALICE DUNBAR-NELSON, COUNTÉE CULLEN, EMMETT JAY SCOTT, and CHARLES S. JOHNSON.

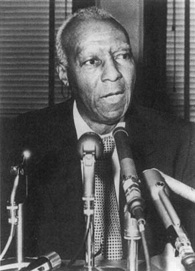

Civil rights leader and editor A. Philip Randolph in 1964. Library of Congress

In the context of the postwar red scare, however, Randolph’s leftist politics brought him to the attention of federal authorities determined to root out radicals, anarchists, and communists but who showed little regard for civil liberties. With the Messenger dubbed “the most dangerous of all Negro publications” by the Bureau of Investigation (later the FBI), Randolph and Owen were arrested under the Espionage Act in 1918 but were eventually acquitted of all charges.

When the Socialist Party split in 1919 over the issue of affiliation with the newly created socialist state in Russia, Randolph and Owen remained in the Socialist Party faction. The left wing of the party broke away, eventually coalescing into the Communist Party, USA (CPUSA). Randolph’s ties to the Socialist Party remained firm, and he ran as the party’s candidate for New York State comptroller in 1920 and as its candidate for secretary of state in 1921. Initial relations with the black CPUSA members were warm, with the communists Lovett Fort-Whiteman and W. A. Domingo writing for the Messenger. By the late 1920s, however, Randolph had become involved in the sometime fractious politics of the black left in the New Negro era.

In the early 1920s Randolph worked for the “Garvey Must Go” campaigns directed by an ad-hoc collection of black leaders opposed to the charismatic—and often belligerent—black nationalist MARCUS GARVEY. Randolph and Garvey had shared a common mentor in the socialist intellectual Hubert Harrison. Randolph claimed, in fact, to have introduced Garvey to the tradition of Harlem street corner oratory. Randolph’s opposition to Garvey appears to have been rooted in his perspective that Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association ignored the “class struggle nature of the Negro problem,” as well as in his belief that Garvey was untrustworthy.

At the same time that W. A. Domingo charged that the Messenger’s attacks on Marcus Garvey had metastasized into a general anti-Caribbean bias, the magazine began devoting much less attention to radical politics in general and Russia specifically. Randolph’s embryonic anticommunism was partially responsible for this shift, but the Messenger had also attempted to broaden its base by appealing to more upwardly mobile black strivers.

With the Messenger in editorial and financial decline, Randolph accepted a position as the head of the newly established Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP) and spearheaded a joint drive for recognition of the union by the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and the Pullman Company. Randolph led the organization to affiliation with the AFL in 1928—a significant accomplishment in the face of the racial discrimination practiced by many of their sibling unions in the AFL. Randolph’s decision to cancel a planned BSCP strike in 1928, however, resulted in a significant loss of confidence in the union and opened him up to criticism from the Communist Party, among others.

The Communist Party-affiliated American Negro Labor Congress, created in 1925, became increasingly critical of Randolph and the BSCP by the end of the decade. At the same time, Randolph’s thinking and writing took a strong and persistent anticommunist turn. In the 1930s the economic upheaval of the Great Depression and the controversial treatment of the wrongfully imprisoned SCOTTSBORO BOYS brought Communists an unprecedented degree of recognition and status within black America. The era’s radicalism found expression in 1935 in the creation of the National Negro Congress (NNC)—an umbrella organization with liberal, radical, and moderate black elements. Randolph was selected as the organization’s first president in 1936. Given his standing as a radical socialist, labor organizer, and civil rights advocate, Randolph was one of the few prominent African Americans with ties to many of the diverse constituencies that made up the NNC.

Global politics shaped the organization from the outset. The NNC had been founded in the midst of the “Popular Front” era and, in many ways, had been facilitated by the shared concern of communists, liberals, socialists, and moderates about the spread of fascism across Europe and the lack of civil rights for blacks in America. However, the Hitler-Stalin Pact of 1939 effectively ended the Popular Front, and tensions within the NNC increased. Randolph resigned in 1940, charging that Communist influence had undercut the NNC’s autonomy and saying famously that “it was hard enough being black without also being red” (press release, 4 May 1940, in NAACP papers, A-444).

World War II brought Randolph a new set of challenges. With America on the verge of the war in 1941, he organized the March on Washington movement, an attempt to bring ten thousand African Americans to Washington to protest discrimination in defense industries. President Franklin Roosevelt, recognizing the possible impact upon morale and public relations and the significance of the black vote in the 1932 and 1936 presidential elections, issued Executive Order 8806, which forbade discrimination in defense industries and created the Fair Employment Practices Commission. In response, the proposed march was cancelled. Randolph, however, remained at the head of the organization until 1946.

In 1948 Randolph, along with BAYARD RUSTIN, with whom he would work closely in later years, organized the League for Nonviolent Civil Disobedience against Military Segregation. The organization’s efforts led to a meeting with President Harry S. Truman in which Randolph predicted that black Americans would not fight any more wars in a Jim Crow army. As with the planned march on Washington, the 1948 efforts influenced Truman’s decision to desegregate the military with Executive Order 9981.

During the 1950s Randolph became more closely aligned with mainstream civil rights organizations like the NAACP—organizations that he had fiercely criticized earlier in his career. He also became more outspokenly anticommunist, traveling internationally with the Socialist Norman Thomas to point out the shortcomings of Soviet Communism. He was elected to the executive council of the newly united AFL-CIO in 1955. The high-water mark of his influence, however, had passed. Randolph did not exert as much influence with the union president George Meany as he had with the AFL president William Green, whom he had known since the BSCP’s affiliation in 1928. In 1959 Randolph assumed the presidency of the Negro American Labor Council (NALC). That same year, Randolph’s address on the subject of racism within the AFLCIO elicited a stern rebuke from Meany. Wedged between the radical younger members of the NALC and his contentious relationship with Meany, Randolph resigned his position in 1964.

Randolph reemerged in the 1960s in connection with the modern civil rights movement; in 1962 Rustin and the seventy-two-year-old Randolph proposed a march on Washington to MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. and the NAACP’s ROY WILKINS. Randolph was the first speaker to address the 200,000 marchers at the Lincoln Memorial on 28 August 1963, stating that “we are not a pressure group, an organization or a group of organizations, we are the advance guard for a massive moral revolution for jobs and freedom.” The march was a decisive factor in the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Randolph presided over the creation of the A. Philip Randolph Institute in 1964 and spearheaded the organization’s efforts to extend a guaranteed income to all citizens of the United States. His anticommunist views led him to support the war in Vietnam—a stance that put him at odds with his onetime ally Martin Luther King, among others. He distrusted the evolving radicalism that characterized the decade, stating that Black Power had overtones of black racism. His public support for the United Federation of Teachers in the Ocean Hill-Brownsville conflict of 1968, in which black community organizations attempted to minimize the authority of the largely white teachers union, further alienated Randolph from the younger generation of Black Power advocates.

By the time of his death in Manhattan in 1979 Randolph had become an icon in the struggle for black equality in the twentieth century. More than any other figure, A. Philip Randolph was responsible for articulating the concerns of black labor—particularly in the context of the civil rights movement. His organizing abilities and strategic acumen were key to the desegregation of defense contracting and the signal legislative achievement of the civil rights era: passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

A. Philip Randolph’s papers are housed in the Library of Congress. Microfilm versions are available at other institutions, including the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture of the New York Public Library.

Anderson, Jervis. A. Philip Randolph (1972).

Kornweibel, Theodore. No Crystal Stair: Black Life and the Messenger, 1917–1928 (1975).

Marable, Manning. “A. Philip Randolph, An Assessment” in From the Grassroots (1980).

Pfeffer, Paula. A. Philip Randolph: Pioneer of the Civil Rights Movement (1990).

Obituary: New York Times, 17 May 1979, Al, B12.

—WILLIAM J. COBB

RANGEL, CHARLES

RANGEL, CHARLES(11 June 1930–), member of the U.S. Congress, was born in Harlem, New York City, the second of three children of Ralph Rangel and Blanche Wharton. When Rangel was still young, his father abandoned them; his mother worked in New York’s garment industry and occasionally did house cleaning to support them. She was active in the International Ladies Garment Workers Union and in Harlem’s civic life. In 1948 Rangel joined the army, serving until 1952; he earned a Purple Heart and a Bronze Star for his service during the Korean War. Discharged as a staff sergeant, Rangel attended New York University on the G.I. Bill and in 1957 earned a BA in Business Administration. In 1960 he earned a law degree from St. John’s University Law School, Brooklyn, and began the practice of law in Harlem, where he also joined the local Democratic Party club. Rangel subsequently worked in a variety of legal positions, including legal assistant to the New York district attorney, counsel to the New York City Housing and Redevelopment Board, and assistant U.S. attorney. In 1964 he married Alma Carter, a social worker, and together they had two children.

In 1966 Rangel’s involvement in Harlem Democratic Party politics paid off, when he was elected to the New York State General Assembly. Rangel’s rise in Harlem politics was promoted by the legendary J. Raymond Jones, the first African American chair of the New York County (Manhattan) Democratic Party Committee. Four years later Rangel defeated another legend in Harlem politics—ADAM CLAYTON POWELL JR.—and was elected to the House of Representatives. Powell, the pastor of one of Harlem’s most influential churches and the first African American elected to the U.S. Congress from New York, for years had been the best-known and most influential black politician in the United States. However, despite his iconic status in Harlem and among African Americans in general, by 1970 he was vulnerable—in 1967 he had been expelled from Congress, and though he was reelected in 1968, his power was greatly diminished. In addition, because of an outstanding civil warrant, Powell could visit Harlem only on Sundays. Rangel seized the opportunity to challenge him, narrowly defeating him in the four-person Democratic primary election. Winning by a mere 150 votes and one percentage point, Rangel was successful mainly as a result of white votes. In a development unrelated to the election, a largely white section of the Upper West Side of Manhattan had been added to Powell’s district. Rangel won in these white areas by fifteen hundred votes. However, like most incumbent members of the House, once elected Rangel was easily returned to office, often running unopposed or winning by margins of victory of 80 percent or more against little-known opponents. The only serious challenge to his reelection occurred in 1994, when Adam Clayton Powell IV, a city councilman and the son of the former congressman, ran against him. Fearing the allure of the Powell name, Rangel raised nearly a million and a half dollars and easily defeated the young Powell.

Rangel came to the House the year several new black members were elected, including Bill Clay of Missouri, Louis Stokes of Ohio, and SHIRLEY CHISHOLM of New York, increasing the size of the black congressional delegation from six to thirteen. Younger and more activist than their senior colleagues, Rangel and these new members decided to form the Congressional Black Caucus. Many white and several of the senior black members of the House, including Robert C. Nix of Pennsylvania and Augustus Hawkins of California, opposed the formation of the caucus, arguing that it was inappropriate for members of Congress to organize on the basis of race. But influenced by the ascendant Black Power philosophy, which called on blacks to establish racially separate organizations, Rangel and his colleagues argued that a caucus of blacks was necessary to advance the interest of blacks in the House, getting good committee assignments, for example, and nationally, through the development and articulation of a black legislative agenda. In 1974 Rangel was elected chair of the caucus, becoming its third chair after Congressmen Charles Diggs and Louis Stokes.

In his first term Rangel was assigned to two relatively minor committees—Public Works and Science and Aeronautics—whose jurisdictions had little to do with issues of concern to Harlem or blacks. However, in his second term he was assigned to the Judiciary Committee, which has jurisdiction over civil rights legislation, and to the Committee on the District of Columbia, which oversees the largely black city of Washington, D.C. Rangel was on the Judiciary Committee in 1974 when, in nationally televised proceedings, it considered articles of impeachment against President Richard Nixon. He spoke and voted in favor of each of the three articles charging Nixon with “high crimes and misdemeanors” that merited impeachment. Nixon resigned shortly after the committee approved the articles. In 1986 Rangel was appointed to the Ways and Means Committee, the oldest, most prestigious, and most powerful House committee, with jurisdiction over taxes, international trade, Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid, and welfare. In 1995 Rangel, the first African American to serve on the committee, became the committee’s ranking Democrat, meaning that he will become its first African American chair if the Democrats win a majority of House seats.

Reflecting the concerns of his district specifically and, to some extent, the concerns of blacks nationwide, Rangel also served on the Select Committee on Crime and the Select Committee on Narcotics Abuse, chairing the latter from 1983 until it was abolished in 1993. More so than many big-city ghettos, Harlem has been plagued by problems of crime and drug trafficking. Rangel used his position of leadership on the Narcotics Committee to press for policies to interdict the flow of drugs into the country and to spend money on rehabilitation as well as incarceration. However, Rangel’s position on narcotics generally has been relatively conservative. For example, he opposed the legalization of marijuana and other drugs and the provision of free needles to addicts to combat AIDS.

Rangel has several important legislative accomplishments to his credit. He was a principal author of federal empowerment zone legislation (1993) and the Targeted Jobs Tax Credit (1978), both designed to attract jobs to low-income areas like Harlem. He also sponsored the Low Income Housing Tax Credit (1986) to encourage home ownership among the poor. And he was a principal author of the Africa Growth and Opportunity Act, legislation designed to encourage trade between the United States and African nations.

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, after more than thirty years in the House, Rangel was one of its most influential and widely respected members. He was also a leading player in national Democratic Party politics and a broker in New York City and New York State politics, successfully maneuvering in 2002 to obtain the Democratic Party nomination for governor for Carl McCall, an African American. He encouraged and helped Hillary Clinton, the wife of the former president, win a seat in the U.S. Senate, representing New York. He was also instrumental in persuading President Bill Clinton to locate his post-presidential office in Harlem. In 2003, as the United States approached war with Iraq, Rangel introduced legislation to reinstate the military draft, arguing that all social classes, rather than mainly the lower-middle class and the poor, should be represented in the military. Like his predecessor, Rangel managed to project his representation of Harlem onto a national platform, where he is recognized as one of the highest ranking and most influential black elected officials in the United States.

Clay, Bill. Just Permanent Interests: Black Americans in Congress, 1870–1991 (1992).

Swain, Carol. Black Faces, Black Interests: The Representation of African Americans in Congress (1993).

—ROBERT C. SMITH

REASON, PATRICK HENRY

REASON, PATRICK HENRY(April? 1816–12 Aug. 1898), printmaker and abolitionist, was born in New York City, the son of Michel Reason, of St. Anne, Guadeloupe, and Elizabeth Melville, of Saint-Dominique. Patrick was baptized as Patrick Rison in the Church of St. Peter on 17 April 1816. While it is not known why the spelling of his name changed, it may have been a homage to the political leader Patrick Henry. While he was still a student at the African Free School in New York, his first engraving was published, the frontispiece to Charles C. Andrews’s The History of the New York African Free-Schools (1830). It carried the byline “Engraved from a drawing by P. Reason, aged thirteen years.” Shortly thereafter, Reason became apprenticed to a white printmaker, Stephen Henry Gimber, and then maintained his own studio at 148 Church Street in New York, where he offered a wide variety of engraving services. Reason was among the earliest and most successful of African American printmakers.

A skilled orator, Reason delivered a speech, “Philosophy of the Fine Arts,” to the Phoenixonian Literary Society in New York on 4 July 1837. (It is unclear whether this association was the same as the Phoenix Society, a benevolent organization that had been founded by the Reverend Peter Williams in 1833.) The Colored American newspaper reported this speech to be “ably written, well delivered, and indicative of talent and research.” In 1838 Reason won first premium (prize) for his India ink drawing exhibited at the Mechanics Institute Fair, and he advertised himself in the Colored American as a “Historical, Portrait and Landscape Engraver, Draughtsman & Lithographer” who could produce “Address, Visiting and Business Cards, Certificates, Jewelry &c., neatly engraved.” He also gave evening instruction in “scientific methods of drawing,” worked for Harpers Publishers preparing map plates, and did government engraving. Reason appeared as a “col’d” (“colored”) engraver in New York City directories from 1846 to 1866.

Perhaps Reason’s best-known works are his copper engravings of chained slaves. The first, featuring a female figure and the caption “Am I Not a Woman and a Sister?” (1835), was a common letterhead of abolitionists from the mid-1830s onward and was reproduced on both British and American antislavery plaques, publications, coins, and medals. (However, while he was a staunch abolitionist, Reason did not initially support women’s rights; he attended the annual meeting of the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1839 and signed a protest against extending the vote to women in the society and against their serving as officers.) A later similar engraving (1839?) depicts a kneeling young male slave wearing tattered clothing, his wrists bound by long, thick manacles. With his head cocked to the side in a forlorn expression, he clasps his hands in prayer. This version, entitled Am I Not a Man and a Brother?, embellished membership certificates of Philadelphia’s Vigilant Committee, a group of young African American activists who aided escaped slaves. The committee’s secretary, Jacob C. White Sr., or its president, Robert Purvis, whose names are on the certificate, may have commissioned the piece. Reason’s source for the imagery may have been Wedgwood relief designs or a seal (1787) bearing the same motto along with a chained kneeling slave in a similar position and attitude, used by the English Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade.

As a freelance engraver and lithographer, Reason produced portraits and designs for periodicals and frontispieces in slave narratives in the mid-nineteenth century. Typically, his portraits were profile or three-quarters, bust-length images of men with stoic expressions and dressed in coats and ties, set against black backgrounds. Examples appear in Lydia Maria Child’s The Fountain for Every Day in the Year (1836), A Memoir of Granville Sharp (1836) for which Reason based his work on an earlier engraving of the British abolitionist and reformer by T. B. Lord, Narrative of James Williams, an American Slave: Who Was Several Years a Driver on a Cotton Plantation in Alabama (1838), John Wesley’s Thoughts on Slavery Written in 1774 (reprinted in 1839), Liberty Bell (1839, “The Church Shall Make You Free”), and Baptist Memorial (members of the London Emancipation Society, the Reverend Baptist Noel and the Reverend Thomas Baldwin). Three works by Reason appeared in the U.S. Magazine and Democratic Review: portraits of the Ohio antislavery senator Benjamin Tappan, after a painting by Washington Blanchard (June 1840 which later appeared in the Annual Obituary Notices in 1857 and 1858); the lawyer and diplomat George Mifflin Dallas (Feb. 1842); and the mathematician Robert Adrain, after a painting by Ingraham (June 1844).

Reason also completed two portraits of the antislavery lecturer HENRY BIBB, a lithograph (1840) and a copper engraving featured in Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Henry Bibb, an American Slave (1849). While the lithograph depicts Bibb standing rigidly before a draped window, the engraving portrays him casually holding a book in his right hand, posed against a dark background. Among Reason’s other works were an engraving of a mountainous landscape after a drawing by W. H. Bartlett and a copper nameplate for Daniel Webster’s coffin. Additional subjects included the slave James Williams (1838), the abolitionist PETER WILLIAMS JR., New York governor De Witt Clinton, and the physician JAMES MCCUNE SMITH. In 1838 Reason arranged a public meeting to honor Smith on his return from a European trip. In 1840 he worked with Smith at the Albany Convention of Colored Citizens in drafting a letter to the U.S. Senate protesting racist remarks made by Secretary of State John C. Calhoun to the British minister to the United States regarding a slave revolt onboard the Creole.

In the 1840s and 1850s Reason was active in a number of civic groups and fraternal orders. He served as secretary of the New York Society for the Promotion of Education among Colored Children, founded in 1847. As a member of the New York Philomath-ean Society, organized in 1830 for literary improvement and social pleasure, he petitioned the International Order of Odd Fellows for the society to become a lodge of the association. Although the application was refused, the society received a dispensation from Victoria Lodge No. 448 in Liverpool and became Hamilton Lodge No. 710 in 1844. Reason served as grand master and permanent secretary of the group in the 1850s. His speech at the annual meeting in 1856 was declared the finest given up to that time. Reason not only developed the secret ritual of the order but also composed the Ruth degree, the first “degree to be conferred under certain conditions on Females,” and in 1858 he was the first person to receive the honor.

Reason also served as grand secretary of the New York Masons from 1859 to 1860 and as grand master from 1862 to 1868, receiving the Thirty-third Degree of Masonry in 1862. Simultaneously, he was grand master of the Supreme Council for the States, Territories, and Dependencies. The printmaker created original certificates of membership for both the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows and the Masonic Fraternity.

Reason may have taught in the New York schools after 1850. Public School No. 1 was associated with the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, an organization with which Reason had close ties. In 1852 MARTIN R. DELANY described Reason in The Condition, Elevation, Emigration, and Destiny of the Colored People of the United States as “a gentleman of ability and a fine artist” who “stands high as an engraver in the city of New York. Mr. Reason has been in business for years… and has sent out to the world, many beautiful specimens of his skilled hand.” Reason also produced other artistic work. During the New York draft riots of 1863, merchants formed a committee for the relief of African American victims. The Reverend HENRY HIGHLAND GARNET wrote an address to the group that was “elaborately engrossed on parchment and tastefully framed by Patrick Reason, one of their own people.”

In 1862 Reason married Esther Cunningham of Leeds, England; the couple had one son. Invited to work as an engraver with several firms in Cleveland, Reason moved to Ohio in 1869 and for the next fifteen years worked for the Sylvester Hogan jewelry firm. When Reason died in Cleveland, he left behind a large body of work that established him as one of the finest printmakers of the nineteenth century.

Brooks, Charles. The Official History and Manual of the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows in America (1871).

Jones, Steven Loring. “A Keen Sense of the Artistic: African American Material Culture in 19th Century Philadelphia.” International Review of African American Art 12.2 (1995).

Porter, James A. Modern Negro Art (1943).

Obituary: Cleveland Gazette, 20 Aug. 1898.

—THERESA LEININGER-MILLER

REED, ISHMAEL

REED, ISHMAEL(22 Feb. 1938–), writer, was born Ishmael Scott Reed in Chattanooga, Tennessee, to Thelma Coleman, a saleslady. Coleman never married Reed’s natural father, Henry Lenoir, a fund-raiser for the YMCA, but before 1940 she married an autoworker, Bennie Reed, whose surname Ishmael received. (Ishmael has seven siblings and half-siblings.) Coleman moved with her children to Buffalo, New York, in 1942, where Ishmael attended two different high schools before graduating in 1956; he also made his initial forays into journalism by writing a jazz column in a local black newspaper the Empire Star, while still a teenager.

Reed began his college studies in evening courses at the University of Buffalo but ascended to the more rigorous daytime curriculum when an instructor read one of his short stories, in which Reed satirized the Second Coming of Christ by making him an advertising agent who is scorned by the industry because of his unique sales approach. “Something Pure,” as the story was titled, gave an early indication of what would become Reed’s inimitable style. Reed had read Nathanael West in high school, and West’s biting social fiction and floating narrative voice were critical influences. In classes at Buffalo, Reed also absorbed the poetry of William Blake and William Butler Yeats, both of whom developed personal mythologies as an integral part of their work.

Reed’s soaring intellectual life at the university was grounded by the meager prospects of a young, black, male adult of the time. Low on money and discontented with academe’s aloofness to social realities, he abandoned school to return as a correspondent with the Empire Star, moved into a Buffalo housing project in order to better assimilate the concerns of the city’s underprivileged black population, and embarked on what turned out to be a discouraging attempt at activism. In one instance, he knocked on doors and registered voters on behalf of a black councilman who covertly threw the election to win favor for another job. In 1961 Reed tried his hand at moderating a radio program that was subsequently cancelled when he and another Star editor interviewed MALCOLM X, who was at the time the controversial spokesman for the Nation of Islam.

Compounding Reed’s professional frustrations were his new responsibilities as a husband and father. In September 1960 he married Priscilla Rose, with whom he had a daughter, Timothy Brett, in 1962. Shortly after his daughter was born, however, Reed left for New York City and officially separated from his wife in 1963.

Determined to become a full-time writer, Reed immersed himself in the literary and creative cityscape of 1960s New York. He extended his literary talents to poetry through his association with the Umbra Workshop, a collective for black poets, and bolstered his journalistic expertise by working for a New Jersey weekly called the Newark Advance, assuming the editorship in 1965. Revamping the Advance inspired Reed to start his own paper, which he accomplished later that year by cofounding the East Village Other, taking the name from Carl Jung’s theory of “Otherness.” Increasingly enamored of the possibilities of cultural collision, Reed was finally beginning to enjoy an artistic career that had expanded sufficiently to satisfy his interests. This creative growth was especially marked by the release of his first novel, The Freelance Pallbearers (1967), a critically successful debut.

The Freelance Pallbearers grew out of Reed’s attempt to parody Newark politics, but it eventually developed into a satire of the United States as a whole—in particular, the volatile social failures of the 1960s and the country’s problematic participation in the Vietnam War. The novel’s stand-in country for the United States is “HARRY SAM,” which, as one critic points out, is a virtual homonym for “harass ’em,” an attitude that Reed asserts the country takes toward its ideological opponents (Fox, 42). Reed directs his satire toward blacks as well, by drawing as his novel’s protagonist Bukka Doopyduk, a black hospital worker representing African Americans who prefer assimilation over social protest. The title refers to the liberals who, in Reed’s story, permit their leaders to be murdered, yet tardily appear over their corpses to praise their work and carry them away. As Henry Louis Gates Jr. asserts, the novel adopts the self-discovering confessional prose that is the most identifiable convention of African American literature, seen most notably for Reed in RALPH ELLISON’S Invisible Man. Through this voice, The Freelance Pallbearers establishes a fundamental element of Reed’s writing; namely, the interrogation of artistic conventions in western culture, both white and black and everything in between.

Roused by the acclaim he received from The Freelance Pallbearers, Reed soon realized he needed to leave New York. His conscientious lower-class background made him suspicious of fame and the damage it would inflict upon his art. “If I had remained,” he later wrote, “I would have been loved and admired to death” (Reader, xiv). So he left for California and eventually settled in Oakland, accepting a guest lecturing position at the University of California at Berkeley. He has held the post ever since, though not without some friction; after a few years he was encouraged to apply for tenure and was then refused, though he was allowed to continue teaching. Oakland proved to be an even more fertile environment for Reed’s creativity than New York, as it cast him among a community of grassroots activist-intellectuals and cultural personalities, such as Cecil Brown, ANGELA DAVIS, and, for a short while in the 1970s, RICHARD PRYOR. He finally divorced Rose in 1940 and married Carla Bank, a dancer, with whom he had his second daughter, Tennessee.

In 1969 Reed released his second novel, Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down, which he has described as an effort to deconstruct (“break down”) the yellowback serial novels of the Old West and, by inference, the history of America. Yellow Back also expands upon Reed’s increasing fascination with aspects of voodoo as a means of restructuring our perspective of American culture. Most telling, however, are Reed’s emerging ideas concerning the novel and art generally, specifically in regard to its potential utilization by underrepresented communities. One character rages, ‘“No one says a novel has to be one thing. It can be anything it wants to be, a vaudeville show, the six o’clock news, the mumblings of wild men saddled by demons. All art must be for the end of liberating the masses.’”

It logically followed that Reed’s next novel, Mumbo Jumbo (1972), would serve as a manic exploration for an authoritative African American text, an entity that, as Reed’s novel powerfully points out, simply does not exist—but this nonexistence only emphasizes that the monolithic text of whiteness and homogeneous western culture holds no true ballast either. Put differently, Mumbo Jumbo is an articulate defense of the dynamism of American race and culture, with particular attention to the instability of the form of the novel. Calling on his own idiosyncratic background in various media—music, radio, newspapers, magazines, and fiction—Reed infuses his novel with photographs, illustrations, charts, footnotes, copies of handbills, door signs, a bibliography, and more. The term Reed chooses for African American culture is “Jes Grew”—a rubric that lays bare the fallacy that African American traditions simply sprang out of nowhere—and in the novel it assumes the form of an epidemic whose victims uncontrollably execute a ragtime dance step, thereby preventing their assimilation in American society.

Mumbo Jumbo was nominated for a National Book Award, the second such honor of Reed’s career; he had been likewise nominated for his first extensive collection of poetry, Conjure, the year before. Both Conjure and Mumbo Jumbo provide a name for Reed’s engagement with African American religion: “Neo-Hoodoo.” An integral figure in Neo-hoodoo is the trickster figure, whom Reed effectively emulates in his writing. Albeit any summation of Neo-hoodoo risks oversimplification, it can best be understood as a politicized and religious response to Judeo-Christian and Islamic ideologies. Reed’s art attempts to reconfigure the motley aggregate of beliefs that Westerners mistakenly hold as unshakable.

By the mid-1970s Reed was accepting awards from the Guggenheim Foundation (1974) and the National Institute of Arts and Letters (1975), among others. Yet with his fourth and fifth novels, as well as a growing corpus of essays that express his vitriol in a more direct manner, the controversy surrounding his work steadily increased. Reviewing Reed’s fourth novel, The Last Days of Louisiana Red (1974), Barbara Smith wrote in the New Republic that Reed was showing a disturbing reliance on “the tired stereotypes of feminists as man-hating dykes” (23 Nov. 1974). And Reed reports that when he accepted an award for the novel, an “inebriated” Ralph Ellison—a longtime opponent of his work—shouted, “Ishmael Reed, you ain’t nothin’ but a gangster and a con artist” (Reader, xviii). With his fifth novel, Flight to Canada, a satirical rewriting of the slave narrative that is generally considered his most accessible work, Reed enjoyed a more positive response.

While Reed would publish four more novels by 1993—The Terrible Twos (1982), Reckless Eyeballing (1986), The Terrible Threes (1989), and Japanese by Spring (1993)—the emphasis of his writing clearly shifted to essays, poetry, and drama. While all of these writings demonstrate a consummate artistry, they rarely achieved for him the notoriety of his early novels. In a way, Reed suffered the mishap of publishing utterly original work in the first half of his career and then being forced to explain himself in the second half—a task he has undertaken grudgingly.

Nonetheless, perhaps the most consistently positive aspect of his career in letters has been his stewardship for culturally underrepresented writers, as an editor of both magazines and anthologies. Toward this end, Reed cofounded the Yardbird Publishing Company in 1971 and the Before Columbus Foundation in 1976, both of which endeavored to gain notice, if not notoriety, for American writers of all ethnic backgrounds. Recently, Reed has edited collections of Native American literature, Asian American literature, and multicultural poetry. With the emergence of the Internet in western literary discourse, Reed also launched, in the late 1990s, a variety of online magazines, most notably KONCH, a forum for current events, and VINES, a serial collection of student writing. In 2000 Reed culled his best work from fiction, poetry, drama, and nonfiction which he collected in The Reed Reader.

By creating an uninhibited space in his work for play and creativity, a space that invokes seemingly every facet of American life, from religion to pop culture, Reed ranks among the country’s preeminent postmodern writers. But unlike the works of Thomas Pynchon and William Gaddis, to name just two other highly esteemed postmodernists, Reed’s writing is infused with a profound social concern that motivates a relentless indictment of the transgressions of modern America against minorities and the lower classes.

Reed, Ishmael. Conversations with Ishmael Reed, eds. Bruce Dick and Amritjit Singh (1995).

_______. The Reed Reader (2000).

Boyer, Jay. Ishmael Reed (1993).

Fox, Robert Elliot. Conscientious Sorcerers (1987).

Gates, Henry Louis, Jr. “The Blackness of Blackness: A Critique on the Sign and the Signifying Monkey” in The Signifying Monkey (1988).

_______. “Ishmael Reed” in Dictionary of Literary Biography (1984).

McGee, Patrick. Ishmael Reed and the Ends of Race (1997).

—DAVID F. SMYDRA JR.

REID, IRA DE AUGUSTINE

REID, IRA DE AUGUSTINE(2 July 1901–15 Aug. 1968), African American sociologist and educator, was born in Clifton Forge, Virginia, the son of Daniel Augustine Reid, a Baptist minister, and Willie Robertha James. He was raised in comfortable surroundings and was educated in integrated public schools in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, and Germantown, a Philadelphia suburb. Reid’s academic promise was as apparent as his family connections were useful. Recruited by President JOHN HOPE of Morehouse College in Atlanta, Georgia, in 1918 Reid completed the college preparatory course at Morehouse Academy and in 1922 received his BA from Morehouse College.

Reid taught sociology and history and directed the high school at Texas College in Tyler from 1922 to 1923. He took graduate courses in sociology at the University of Chicago the next summer. From 1923 to 1924 he taught social science at Douglas High School, Huntington, West Virginia. Reid then embarked on a model apprenticeship that George Edmund Haynes, cofounder of the National Urban League, had established for social welfare workers and young social scientists as part of the Urban League program. Selected as a National Urban League fellow for the year 1924–1925, Reid earned an MA in Social Economics at the University of Pittsburgh in 1925, and that same year he married Gladys Russell Scott. They adopted one child.

Also in 1925 Reid was appointed industrial secretary of the New York Urban League, a position he held until 1928. In this role he worked with CHARLES S. JOHNSON, director of research and investigations of the National Urban League, helping the league position itself as a source of information about the economic conditions of African Americans as well as an agency for social reform. Reid surveyed the living conditions of low-income Harlem African American families, conducted a study that was published as The Negro Population of Albany, New York (1928), and served as Johnson’s research assistant in a National Urban League survey of blacks in the trade unions.

Reid also served as Johnson’s assistant in collecting data for the National Interracial Conference of 1928 held in Washington, D.C. This conference represented a popular front of “new middle-class” social welfare activists and social scientists, white and black, who were professionally concerned with the race problem in the United States. The conference produced the landmark Negro in American Civilization: A Study of Negro Life and Race Relations in the Light of Social Research (1930). It was a volume that witnessed the emergence of a liberal consensus on race that would be reaffirmed by Gunnar Myrdal in 1944 in An American Dilemma and certified by the U.S. Supreme Court a decade later.

Reid’s three-year tenure as industrial secretary completed another phase of his apprenticeship. In 1928 he succeeded Johnson as director of research for the national body, a position he held until 1934. As part of the league’s procedure for establishing local branches, Reid’s work included surveying seven black communities, which resulted in two important reports, Social Conditions of the Negro in the Hill District of Pittsburgh (1930) and The Negro Community of Baltimore—Its Social and Economic Conditions (1935). Drawing on earlier Urban League research, Reid also published one of the first reliable studies of blacks in the workforce, Negro Membership in American Labor Unions (1930).

Reid was enrolled as a graduate student in sociology at Columbia University throughout the period 1928–1934. While employed by the Urban League he began the research on West Indian immigration on which his PhD dissertation would be based.

In 1934 Hope, then president of Atlanta University, encouraged W. E. B. DU BOIS, chair of the Department of Sociology, to hire Reid. Du Bois complied happily. Reid, he remarked in 1937, “is the best trained young Negro in sociology today.” Six feet four inches tall, confident, well dressed, and witty, Reid was an impressive figure. His biting intelligence was acknowledged—if not always appreciated—and his urbane manner made him an effective interracial diplomat in an era when black equality was an implausible hypothesis for most white Americans.

Reid worked closely with Du Bois at Atlanta University until the latter’s forced retirement in June 1944, at which time he ascended to chair of the Department of Sociology, serving from 1944 to 1946. Having served under Du Bois as managing editor of Phylon: The Atlanta University Review of Race and Culture since 1940, the year of its founding, Reid also succeeded his senior colleague as editor in chief of the journal (1944–1948).

From 1934 until his departure from Atlanta University in 1946, Reid’s work as a social scientist also had important policy implications. Under the auspices of the Office of the Adviser on Negro Affairs, Department of the Interior, Reid directed a 1936 survey of The Urban Negro Worker in the United States, 1925–1936 (vol. 1, 1938), an undertaking financed by the Works Progress Administration. Three years later The Negro Immigrant: His Background, Characteristics and Social Adjustment, 1899–1937 (1939) was published; it was based on the dissertation that had earned him a PhD in Sociology from Columbia University that same year. In 1940 Reid published In a Minor Key: Negro Youth in Story and Fact, the first volume of the American Youth Commission’s study of black youths. This was a cooperative endeavor of anthropologists, psychiatrists, and sociologists to study the impact of economic crisis and minority-group status on the development of youngsters in black communities. From the standpoint of the history and politics of the social sciences, the project—funded by the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial—reflected the Social Science Research Council’s endorsement of a “culture and personality” paradigm that would support liberal policy initiatives.

While at Atlanta Reid also drafted “The Negro in the American Economic System” (1940), a research memorandum used by Myrdal in An American Dilemma four years later. In 1941, in collaboration with sociologist Arthur Raper of the Commission on Interracial Cooperation, Reid published Sharecroppers All, a pioneering study of the political economy of the South. The text reflects the emerging characterization of the depression South by social scientists and New Dealers as the country’s number one economic problem; it signaled their growing impatience at the public costs of the region’s class and race relations and dysfunctional labor market.

After Du Bois’s retirement from Atlanta University, Reid grew restless there. As a result of his desire for more congenial academic surroundings, on the one hand, and the cracks emerging in the walls of segregation, on the other, Reid became one of the first black scholars to obtain a full-time position at a northern white university (New York University, 1945).

This was again an exemplary chapter in his life. Under the racial regime of “separate-but-equal,” job opportunities for black scholars, however well trained and qualified, were restricted to historically black institutions in the South. However, in the early 1940s, as tactical Trojan horses in a foundation-sponsored campaign to desegregate the ranks of the professoriat, a handful of accomplished black academics—among them anthropologist Allison Davis and historian JOHN HOPE FRANKLIN—were installed at northern institutions. Reid became visiting professor of sociology at the New York University School of Education (1945–1947) and, sponsored by the American Friends Service Committee, was visiting professor of sociology at Haverford College, Haverford, Pennsylvania (1946–1947). In 1948 Reid became professor of sociology and chair of the Haverford Department of Sociology and Anthropology, a position he held until his retirement in 1966.

Reid and his wife joined the Society of Friends in 1950, and over the next fifteen years he was involved increasingly in the educational activities of the American Friends Service Committee. Though Reid’s scholarly output decreased during this period, his important earlier contributions were gradually acknowledged. He was named assistant editor of the American Sociological Review (1947–1950). Ironically, with the coming of the McCarthy era, Reid was honored for professional contributions that now earned him public suspicion. His passport was suspended from 1952 to 1953 by State Department functionaries for suspected communist sympathies. When he firmly challenged this action, the passport was soon returned. Reid served as vice president and president of the Eastern Sociological Society from 1953 to 1954 and from 1954 to 1955, respectively. He was elected second vice president of the American Sociological Association itself from 1954 to 1955.

After the milestone 1954 Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education, Reid was invited to edit “Racial Desegregation and Integration,” a special issue of the Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science (304 [Mar. 1956]). This was another indication of his new visibility within the social science fraternity.

Reid’s wife died in 1956. Two years later he married Anna “Anne” Margaret Cooke of Gary, Indiana.

Late in his career Reid enjoyed a wider public. Among other activities, he served on the Pennsylvania Governor’s Commission on Higher Education and was a participant in the 1960 White House Conference on Children and Youth. In 1962 Reid was visiting director, Department of Extra-mural Studies, University College, Ibadan, Nigeria. From 1962 to 1963 he was Danforth Foundation Distinguished Visiting Professor, International Christian University, Tokyo, Japan. Reid retired as professor of sociology at Haverford College on 30 June 1966. He died in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania.

In addition to his personal achievements, Ira Reid is an important representative of the first numerically significant cohort of professional black social scientists in the United States.

No comprehensive collection of Reid manuscript materials exists. However, information about Reid, the various projects and organizations with which he was associated, as well as relevant memoranda and correspondence may be found in the John Hope Presidential Papers and the Phylon Records, Editorial Correspondence (1940–1948), Special Collections/Archives, Robert W. Woodruff Library, Atlanta University; and in the Charles S. Johnson Papers and the Julius Rosenwald Fund Archives (1917–1948), Special Collections, Fisk University Library, Nashville, Tenn. See also the Ira De A. Reid File, Office of College Relations, Haverford College, and Ira De A. Reid File, Quaker Collection, Haverford College Library, Haverford, PA; Ira De Augustine Reid Papers, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Rare Books, Manuscripts, and Archives Section, of the New York Public Library.

“Ira De A. Reid” in Black Sociologists: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives, eds. James E. Blackwell and Morris Janowitz (1974), 154–155.

Ives, Kenneth, et al. Black Quakers: Brief Biographies (1986).

Obituaries: New York Times, 17 Aug. 1968; Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, 19 Sept. 1968.

—PAUL JEFFERSON

REMOND, CHARLES LENOX

REMOND, CHARLES LENOX(1 Feb. 1810–22 Dec. 1873), abolitionist and civil rights orator, was born in Salem, Massachusetts, the son of John Remond and Nancy Lenox, prominent members of the African American community of that town. His father, a native of Curaçao, was a successful hairdresser, caterer, and merchant. Charles attended Salem’s free African school for a time and was instructed by a private tutor in the Remond household. His parents exposed him to antislavery ideas, and abolitionists were frequent guests in their home. He crossed the paths of a number of fugitive slaves while growing up and by the age of seventeen considered himself an abolitionist. He had also developed considerable oratorical talent.