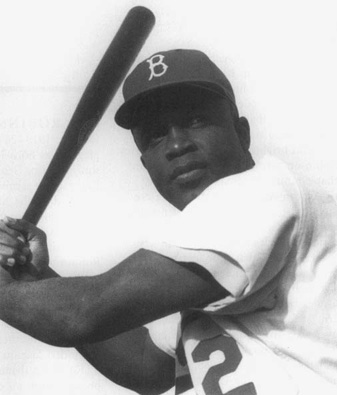

Jackie Robinson at bat for the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1954, seven years after he broke the color line in major league baseball for the first time since 1885. Library of Congress

Robinson dropped out of college during his senior year at UCLA to help support his family. After brief stints as an assistant athletic director at a National Youth Administration camp in California and as a player with two semiprofessional football teams—the Los Angeles Bulldogs and the Honolulu Bears—Robinson was drafted into the U.S. Army in the spring of 1942.

The U.S. Army of the 1940s was a thoroughly segregated institution. Although initially denied entry into the army’s Officers Candidate School because of his race, Robinson, with the assistance of boxer JOE LOUIS, successfully challenged his exclusion and was eventually commissioned a second lieutenant. Robinson spent two years in the service at army bases in Kansas, Texas, and Kentucky. During this time Robinson confronted the army’s discriminatory racial practices; on one occasion he faced court-martial charges for insubordination arising from an incident in which he refused to move to the back of a segregated military bus in Texas. A military jury acquitted Robinson, and shortly thereafter, in November 1944, he received his honorable discharge from the army.

Following his discharge, Robinson—who continued to enjoy a reputation as an extraordinarily gifted athlete—spent the spring and summer of 1945 playing shortstop with the Kansas City Monarchs in the Negro Leagues. Robinson proved to be a highly effective player, batting about .345 for the year. At this time major league baseball did not permit black players to play on either minor league or major league teams, pursuant to an unwritten agreement among the owners that dated back to the nineteenth century. Pressure to integrate baseball, however, had steadily increased. Many critics complained of the hypocrisy of requiring black men to fight and die in a war against European racism but denying them the opportunity to play “the national pastime.” During the early 1940s a few major league teams offered tryouts to black players—Robinson had received a tryout with the Boston Red Sox in 1945—but no team actually signed a black player.

In the meantime, however, Branch Rickey, president of the Brooklyn Dodgers baseball team, had secretly decided to use African Americans on his team. Rickey was convinced of the ability of black ballplayers, their potential gate attraction, and the injustice of their exclusion from major league baseball. Using the ruse that he wanted to develop a new league for black players, Rickey deployed his scouts to scour the Negro Leagues and the Caribbean for the most talented black ballplayers during the spring and summer of 1945. In particular Rickey sought one player who would break the color line and establish a path for several others to follow; he eventually settled on Robinson. Although Robinson was not the best black baseball player, his college education, experience competing in interracial settings at UCLA, and competitive fire attracted Rickey. In August 1945 Rickey offered Robinson a chance to play in the Dodgers organization but cautioned him that he would experience tremendous pressure and abuse. Rickey extracted from Robinson a promise not to respond to the abuse for his first three years.

Robinson spent the 1946 baseball season with the top Dodgers minor league club located in Montreal. After leading the Montreal Royals to the International League championship and winning the league batting championship with a .349 average, he joined the Dodgers the following spring. Several of the Dodgers players objected to Robinson’s presence and circulated a petition in which they threatened not to play with him. Rickey thwarted the boycott efforts by making clear that such players would be traded or released if they refused to play.

Robinson opened the 1947 season as the Dodgers’ starting first baseman, thereby breaking the long-standing ban on black players in the major leagues. During his first year he was subjected to extraordinary verbal and physical abuse from opposing teams and spectators. Pitchers threw the ball at his head, opposing base runners cut him with their spikes, and disgruntled fans sent death threats that triggered an FBI investigation on at least one occasion. Although Robinson possessed a fiery temper and enormous pride, he honored his agreement with Rickey not to retaliate to the constant stream of abuse. At the same time he suffered the indignities of substandard segregated accommodations while traveling with the Dodgers.

Robinson’s aggressive style of play won games for the Dodgers, earning him the loyalty of his teammates and the Brooklyn fans. Despite the enormous pressure that year, he led the Dodgers to their first National League championship in six years and a berth in the World Series. Robinson, who led the league in stolen bases and batted .297, was named rookie of the year. Overnight, he captured the hearts of black America. In time he became one of the biggest gate attractions in baseball since Babe Ruth, bringing thousands of African American spectators to major league games. Five major league teams set new attendance records in 1947. By the end of the season, two other major league teams—the Cleveland Indians and the St. Louis Browns—had added black players to their rosters for brief appearances. By the early 1950s most other major league teams had hired black ballplayers.

In the spring of 1949, having fulfilled his three-year pledge of silence, Robinson began to speak his mind and angrily confronted opposing players who taunted him. He also enjoyed his finest year, leading the Dodgers to another National League pennant and capturing the league batting championship, with a .342 mark, and the most valuable player award. Off the field, Robinson received considerable attention for his testimony in July 1949 before the House Committee on Un-American Activities in opposition to PAUL ROBESON’s statement that African Americans would not fight in a war against the Soviet Union. During the next few years Robinson, unlike many other black ballplayers, became outspoken in his criticism of segregation both inside and outside of baseball.

Robinson ultimately played ten years for the Dodgers, primarily as a second baseman. During this time his team won six National League pennants and the 1955 World Series. Robinson possessed an array of skills, but he was known particularly as an aggressive and daring base runner, stealing home nineteen times in his career and five times in one season. In one of the more memorable moments in World Series history, Robinson stole home against the New York Yankees in the first game of the 1955 series. Robinson’s baserunning exploits helped to revolutionize the game and to pave the way for a new generation of successful base stealers, particularly Maury Wills and Lou Brock. Robinson batted .311 for his career and in 1962 became the first black player to win election to the National Baseball Hall of Fame. On 15 April 1997, the fiftieth anniversary of Robinson’s first major league game, Major League Baseball, in an unprecedented action, retired Robinson’s number 42 in perpetuity.

After the 1956 season, the Dodgers traded Robinson to the New York Giants, their crosstown rivals. Robinson declined to accept the trade and instead announced his retirement from baseball. Thereafter, Robinson worked for seven years as a vice president of the Chock Full O’Nuts food company, handling personnel matters. An important advocate of black-owned businesses in America, Robinson helped establish several of them, including the Freedom National Bank in Harlem. He also used his celebrity status as a spokesman for civil rights issues for the remainder of his life. Robinson served as an active and highly successful fundraiser for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and conducted frequent fund-raising events of his own to support civil rights causes and organizations. He wrote a regular newspaper column throughout the 1960s in which he criticized the persistence of racial injustice in American society, including the refusal of baseball owners to employ blacks in management. Shortly before his death, Robinson wrote in his autobiography I Never Had It Made that he remained “a black man in a white world.” Although a supporter of Richard Nixon in the 1960 presidential campaign, Robinson eventually became involved with the liberal wing of the Republican Party, primarily as a close adviser of New York governor Nelson Rockefeller.

Robinson had married Rachel Isum in 1946, and the couple had three children. Robinson suffered from diabetes and heart disease in his later years and died of a heart attack in Stamford, Connecticut.

Probably no other athlete has had a greater sociological impact on American sport than did Robinson. His success on the baseball field opened the door to black baseball players and thereby transformed the game. He also helped to facilitate the acceptance of black athletes in other professional sports, particularly basketball and football. His influence spread beyond the realm of sport, as he emerged in the late 1940s and 1950s as an important national symbol of the virtue of racial integration in all aspects of American life.

The National Baseball Library and Archive in Cooperstown, N.Y., contains extensive material on Robinson. The Arthur Mann and Branch Rickey papers, both located in the Library of Congress, also contain documentary material on Robinson.

Robinson, Jackie. Baseball Has Done It (1964).

_______, with Alfred Duckett. I Never Had It Made (1972).

_______, with Wendell Smith. Jackie Robinson: My Own Story (1948).

_______, with CARL ROWAN. Wait Till Next Year (1960).

Falkner, David. Great Time Coming: The Life of Jackie Robinson, from Baseball to Birmingham (1995).

Frommer, Harvey. Rickey and Robinson: The Men Who Broke Baseball’s Color Barrier (1982).

Robinson, Rachel. Jackie Robinson: An Intimate Portrait (1996).

Tygiel, Jules. Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy (1983).

Obituary: New York Times, 25 Oct. 1972.

—DAVISON M. DOUGLAS

ROBINSON, JAMES HERMAN

ROBINSON, JAMES HERMAN(24 Jan. 1907–6 Nov. 1972), minister and founder of Operation Crossroads Africa, was born in Knoxville, Tennessee, one of six children of Henry John Robinson, a slaughterhouse laborer, and Willie Bell Banks, a washerwoman. Robinson grew up in abject poverty in a section of town called the Bottoms, where poor blacks and whites lived. Because of his father’s frequent periods of unemployment and his mother’s failing health, the Robinson family could not escape the reality of poverty and segregation in the Jim Crow South. Those already at the bottom of the economic pile were also denied access to the educational opportunities that might otherwise have helped them to escape poverty. Given the dire circumstances in which the family lived, James had a difficult time accepting the strong religious convictions of his father, who was a member of a sanctified church and spent much of his free time there. As his family’s economic conditions remained unchanged, James began to view religion as a waste of time, and questioned his father’s and his own faith in God.

In 1917 the Robinson family moved to Cleveland, Ohio, to escape poverty and segregation, but the greater opportunities they had anticipated remained elusive. Robinson attended an integrated school for the first time and found the experience unsettling because of the discrimination he faced from white teachers and students. His father did find work, in another slaughterhouse, but the family continued to live in poverty and in overcrowded housing. Because of these economic hardships, Robinson was not encouraged to remain in school. After his mother died, he moved to Youngstown, Ohio, to live with his grandparents, but was forced to return to Cleveland after the death of his grandmother. Henry Robinson, who had since remarried, had little interest in furthering his son’s desire to get an education. James, nevertheless, found various jobs to support himself and, without his father’s knowledge, attended Fairmont Junior High School and East Technical High School.

Even as a child, Robinson understood that racism was nefarious and contradictory to Christian teaching. His thoughts and feelings on this issue intensified after he moved north to the “Promised Land,” because, although there were no “white” and “colored” signs to dictate where and how one lived, invisible racial boundaries continued to restrict his mobility and opportunities. Robinson’s early life had been marked by many negative experiences, but there were also positive ones, most notably at the Cedar Branch Hi-Y Club, a high school chapter of the YMCA. Before coming to Hi-Y, Robinson was discouraged and distraught, but his experiences at the club expanded his worldview through interaction with middle- and upper-middle-class African Americans. He joined the debate club and through its outings he learned more of himself, the state of race relations, and the role and importance of religion. Ernest Escoe, the debate club’s adviser, and Escoe’s wife, Sally, supported Robinson and encouraged him to attend St. James African Methodist Church. It was there that he found his calling in life: “to be a servant of the people” (Road without Turning, 132). Robinson graduated from East Technical High School in 1929 at the age of twenty-two, but money problems continued to hinder him. He would have been homeless if it were not for Percy and Daisy Kelley. Percy, a waiter in a coffee shop, befriended Robinson, and the Kelleys allowed him to share their home.

Robinson continued his education at Western Reserve University in Cleveland, but dropped out due to financial problems. He then approached the minister of Mount Zion Congregational Church with a plan for a sports program to keep young men out of trouble; after Robinson had established several more clubs, a Presbyterian minister noticed his hard work and informed him that the church would fund his education. He enrolled at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, but because the church did not provide enough funding to support him completely, Robinson spent his summers serving as pastor of a church in Beardon, Tennessee, near Knoxville. He described the social and economic conditions in Beardon as worse than the Bottoms, and used the pulpit to speak out against racial injustice and for civil rights. Robinson’s experiences at Beardon, along with those at Lincoln, further expanded his understanding of race relations and the plight of the less fortunate. Because he was older than most of his classmates, Robinson found the practice of freshmen and fraternity hazing immature and self-defeating. Even more perplexing to him was the fact that, although Lincoln was a historically black college, most of the faculty and administration were white. Robinson spoke out against this glaring inequality throughout his time at Lincoln, where he graduated in 1935 at the top of his class.

After graduating from Lincoln, Robinson attended New York City’s Union Theological Seminary (1935–1938), where he was president of his senior class, and director of the Morningside Community Center (1938–1961). In spite of those successes, his time at Union Seminary was troubled. He tried to uphold Christian values while enduring discrimination from his white classmates. But he also found it difficult to befriend other African American students, as he found them aloof and indifferent to the racism and discrimination they faced. Robinson’s seminary experiences encouraged him to propose greater multiracial cooperation within the ministry.

The year 1938 proved to be a turning point in Robinson’s life: he graduated from Union, was ordained as a minister, became head of Church of the Master Presbyterian Church in Harlem, and married Helen Brodie. They had no children. He also worked as a youth director for the NAACP from 1938 to 1940.

For the rest of his career and life, Robinson saw his mission as being a servant of the people. He believed that his ministry and church could improve communities by providing people with the economic and social resources that they need to empower themselves. Believing that interracial cooperation was central to this goal, he recruited mainly white students from colleges in New York City to work on projects near his church in Harlem. These projects were very successful, and in 1948 land was donated in New Hampshire to establish Camp Rabbit Hollow, a rural setting in which black children from Harlem and white college students could interact and work together, fostering mutual understanding, cooperation, and respect.

The success of these interracial programs, and his experiences touring Africa, Asia, and Europe in the 1950s, encouraged Robinson to found Operation Crossroads Africa in 1958. Believing that “men will lose consciousness of their differences and divisions when they interest themselves in the common problems of one another” (Jet obituary, 48), Robinson encouraged American students and other volunteers to work on community development projects in Africa. In its first twenty years, over 5,000 American volunteers of all races traveled to Africa and the Caribbean to help build and repair housing, roads, health clinics, and schools. Civil rights activists figure prominently among Operation Crossroads alumni, including ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON, later chair of the EEOC and a U.S. congresswoman, who helped build a school in Gabon in the early 1960s. That experience, Norton recalled in 1977, “made me think about myself as a black person and as an American more profoundly than at any point since” (Rule, 58).

Robinson continued to focus on African affairs throughout the 1960s. His development efforts gained worldwide admiration and spurred other transnational volunteer programs, including Canadian Crossroads International and the U.S. Peace Corps, which John F. Kennedy founded in 1961. President Kennedy recognized his debt to Robinson by calling Operation Crossroads Africa “the progenitor of the Peace Corps” (Rule, 58). During the 1950s Robinson published four books, Tomorrow Is Today (1954), Adventurous Preaching, Love of This Land, and Christianity and Revolution in Africa (all 1956). Following his divorce from Helen Brodie in 1954, he married Gertrude Cotter in 1958. The couple had no children. In 1962, he resigned from Church of the Master to be a minister-at-large and to direct Operation Crossroads Africa on a full-time basis. That same year, he published Africa at the Crossroads.

James Robinson died in New York City in 1972, having dedicated his life to fostering a better understanding among people throughout the world. His greatest achievement lay in forging links between Africans and African Americans and between Africa and the United States. “The darkest thing about Africa,” Robinson once remarked, “is America’s ignorance of it” (Rule, 58). Since 1958 Operation Crossroads Africa has worked diligently to remove that veil of ignorance.

James Robinson’s papers are housed in the Amistad Research Center at Tulane University in New Orleans.

Robinson, James Herman. Road without Turning: The Story of Reverend James H. Robinson (1950).

_______. Tomorrow Is Today (1954).

Lee, Amy. Throbbing Drums: The Story of James H. Robinson (1968).

Plimpton, Ruth. Operation Crossroads Africa (1962).

Rule, Sheila. “A Peace Corps Precursor Observes 20th Anniversary of its Founding.” New York Times, 4 Dec. 1977, 58.

Obituary: Jet, 30 Nov. 1972.

—CASSANDRA VENEY

ROBINSON, JO ANN

ROBINSON, JO ANN(17 Apr. 1912–29 Aug. 1992), civil rights activist, was born Jo Ann Gibson on a farm in Crawford County, Georgia, the youngest of twelve children of Owen B. Gibson and Dollie Webb. After the death of her father in 1918, her mother struggled to operate the farm. In 1926, however, her mother sold out and moved the family to the nearby city of Macon, to live with a son who was a postman. Jo Ann attended high school in Macon, graduating in 1929 as the valedictorian of her class. She then began teaching in the Macon public schools, continuing to do so while also attending Fort Valley State College. She received a BS degree from Fort Valley in 1936. In 1943 she married Wilbur Robinson, a soldier in the U.S. Army, and in 1944 they had a child. But the child died in infancy, and in 1946 the Robinsons divorced. Robinson then resigned her position with the Macon school system and entered graduate school at Atlanta University, from which she received an MA in 1948. In the school year 1948–1949 she taught English at Mary Allen College in Crockett, Texas, and in the fall of 1949 she joined the faculty of Alabama State College for Negroes in Montgomery.

Almost as soon as she arrived in Montgomery, she became an active member of the Women’s Political Council, which had been formed the preceding spring by female Alabama State College faculty as a black analogue of the all-white League of Women Voters. Robinson became the council’s president in 1952 and registered to vote for the first time on 6 January 1953. As early as October 1952 the council had begun pressing the Montgomery bus company and the Montgomery City Commission to adopt the pattern of bus segregation in use in the Alabama city of Mobile, under which drivers could not unseat black passengers to make room for boarding whites. Robinson became the principal black spokesperson in meetings with city authorities during 1953 and 1954 about racial problems on the city buses. These meetings rectified one significant black complaint, that buses would stop at every corner in white neighborhoods but only at every other corner in black areas. But no progress was made on the problem of the unseating of black passengers.

On 21 May 1954, just after the U.S. Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision forbidding racial segregation in public schools, Robinson sent Mayor William A. Gayle a letter warning him that unless concessions on the bus-seating question were made, Montgomery’s blacks might undertake a boycott of the busses. The arrest and conviction of a black high school student, Claudette Colvin, in March 1955 for failing to obey a driver’s order to yield her seat, further exacerbated the tensions surrounding this issue. Thus, when the black attorney Fred D. Gray called Robinson on the evening of 1 December 1955 to tell her of the arrest of ROSA PARKS under exactly the same circumstances, Robinson was primed for action. Early the next morning she went to her office at Alabama State College and mimeographed a leaflet calling for a one-day boycott of the buses on the day Parks’s trial was to be held, 5 December. She and her council associates spent the rest of the day distributing the leaflets throughout the black sections of the city. The result was that when Montgomery’s black leaders met that evening at the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, at the call of EDGAR D. NIXON, president of the local of the Pullman porters’ union, to discuss the possibility of a boycott, they found themselves faced with a fait accompli because of Robinson’s actions, and so they voted to support the boycott proposal.

The boycott on 5 December proved to be a complete success. When Parks was convicted and fined ten dollars and costs, black leaders at a meeting that afternoon decided to continue the boycott until the bus company adopted the Mobile pattern of segregation. They formed an organization to run the protest, the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA), and chose Robinson’s pastor, the Reverend MARTIN LUTHER KING JR., to head it. During the boycott, which lasted for more than a year, Robinson continued to play a crucial role. She was one of the black negotiators who met with a white mediation committee appointed by the mayor, and she insisted that the two racial delegations be equal in numbers. She was also a member of the Improvement Association’s executive board and its strategy committee. In this role, she was a central figure in persuading these bodies in January 1956 to agree to file suit in federal court challenging the constitutionality of bus segregation, even though doing so meant abandoning the demand for the adoption of the Mobile pattern of seating. Both during and after the boycott, she edited the MIA’s newsletter, which assisted in raising contributions for the organization from throughout the country.

She had promised the president of Alabama State College, H. Councill Trenholm, that she would keep secret her part in initiating the boycott, to protect the college from state legislative reprisal, and her contributions did not become publicly known until 1980, when historical investigation finally revealed them. Nevertheless, she found herself caught up in Governor John M. Patterson’s furious attacks on the college when its students organized sitins at segregated Montgomery facilities in the spring of 1960, and she was compelled to resign from the faculty in May of that year. She taught at Grambling College in Louisiana during the academic year 1960–1961 and then became a public school teacher in Los Angeles, California. She taught in Los Angeles until her retirement in 1976. In 1987 the University of Tennessee Press published her memoir, The Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Women Who Started It.

Robinson, Jo Ann Gibson. The Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Women Who Started It: The Memoir of Jo Ann Gibson Robinson (1987).

King, Martin Luther, Jr. Stride toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story (1958).

Thornton, J. Mills, III. Dividing Lines: Municipal Politics and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Montgomery, Birmingham, and Selma (2002).

—J. MILLS THORNTON III

ROBINSON, JOHN C.

ROBINSON, JOHN C.(26 Nov. 1903–27 Mar. 1954), aviator who promoted flight training for African Americans but gained his greatest fame as a pilot for Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie, was born in Carabelle, Florida. His father’s name is unknown; his mother, Celest Robinson, may have been born in Ethiopia. Raised by his mother and stepfather in Gulfport, Mississippi, Robinson graduated from Tuskegee Institute in Alabama in 1924. For the following six years, he was a truck driver in Gulfport. Then he moved to Chicago, where he and his wife, Earnize Robinson, operated a garage. In 1931 he graduated from the Curtiss-Wright Aeronautical Institute in Chicago. He taught at Curtiss-Wright Institute and organized African American men and women pilots in the Chicago area into the Challenger Air Pilots Association.

Early in 1935 the Tuskegee Institute invited Robinson to organize the first course in aviation entirely for African Americans. By that time, he held a transport flying license and had piled up 1,200 hours of flight time, much of it as an instructor at South Side Chicago airports. At about the same time as the Tuskegee offer, a nephew of Emperor Haile Selassie invited Robinson to come to Ethiopia. Benito Mussolini’s Italian legions were threatening, and Ethiopia needed experienced aviators, even though some press reports at the time said that none of the emperor’s twenty-five airplanes was flyable. Robinson appeared to have selfless motives, in contrast with the many intriguers and opportunists who flocked into Addis Ababa during Ethiopia’s futile attempts to repel the Italians. He “had come to Ethiopia to testify to the solidarity of the colored peoples” (Del Boca, 86).

Soon after arriving, Robinson displayed what would become a familiar penchant for prickly behavior toward others. He clashed with the only other African American pilot on the scene, Col. Hubert Julian, a Harlem native who had renounced his U.S. citizenship to serve in the Ethiopian air force. Julian, known as the “Black Eagle,” apparently lost the contest, because he was banished to a far-off province to drill infantry recruits. That left Robinson, the “Brown Condor,” in charge of the ragtag air force. Now a colonel, he had to deal with an Italian air force that controlled the skies over Ethiopia during the invasion in 1935 and 1936. In an unarmed monoplane, he repeatedly flew courier missions between the front lines and Addis Ababa. Robinson escaped from Ethiopia on 4 May 1936, the day before the country capitulated. Returning to the United States, he toured the country on behalf of United Aid for Ethiopia. That fall, he returned to Tuskegee Institute to teach the aviation course he had given up before he left for Ethiopia.

When World War II ended, Robinson returned to Ethiopia, where Selassie granted him his old rank of colonel. Within a year, however, he was at odds with a group of Swedish technicians who were in Ethiopia to work with equipment sent by Swedish munitions makers. In August 1947 the conflict exploded into violence. Robinson was arrested and jailed for an assault on Swedish Count Carl Gustav von Rosen, who was then commander in chief of the Ethiopian air force. Robinson was found guilty by a jury, lost his appeal, and spent an undetermined amount of time in prison.

In 1951 Ebony magazine reported that Robinson—still the best-known African American in Ethiopia—had become disillusioned by his conviction and was thinking of returning to the United States. “But,” said Ebony’s reporter, “despite Selassie’s apparent indifference to him, he remains something of a national hero to the Ethiopian people.”

Robinson died as a result of severe burns sustained on 13 March 1954, when the training plane he was flying crashed and burned at the Addis Ababa airport, after narrowly missing a nurses’ home. The apparent cause of the accident was engine failure. Also killed in the accident was Bruno Bianci, an Italian engineer.

Although Robinson was a glamorous figure in Ethiopia’s highly publicized resistance to Mussolini, his greatest legacy may have been his attempt to increase African American interest in aviation in the United States. Had he remained in his native country after World War II, he would have witnessed the integration of the armed forces—perhaps by some of the pilots he helped train.

Del Boca, Angelo. The Ethiopian War, 1935–1941 (1965; Eng. trans. 1969).

Gubert, Betty Kaplan. Invisible Wings: An Annotated Bibliography on Blacks in Aviation, 1916–1993 (1994).

Scott, William R. The Sons of Sheba’s Race: African Americans and the Italo-Ethiopian War, 1935–1941 (1993), 69–80.

Obituaries: Chicago Tribune and New York Times, 28 Mar. 1954.

—DAVID R. GRIFFITHS

ROBINSON, RANDALL

ROBINSON, RANDALL(6 July 1941—), lawyer, human rights activist, and founder and president of TransAfrica and TransAfrica Forum, was born in Richmond, Virginia, one of four children of Maxie Cleveland Robinson Sr., a high school history teacher, and Doris Alma Jones, an elementary school teacher. His sister Jewell was the first African American admitted to Goucher College in Maryland, and his brother Max was the first African American to anchor a national news program. Although both his parents attended college, the family experienced poverty early on, like most African American families living in Richmond at the time. Robinson attended public schools and felt the effects of racism and discrimination as he negotiated his way within the confines of a segregated society.

Following graduation from high school in 1959, Robinson attended Norfolk State College in Virginia on a basketball scholarship, but he left the university during his junior year. He married Brenda Randolph, a librarian, in 1965. They had two children, Anike and Jabari, before divorcing in 1982. Robinson served in the army, and, following his discharge, attended Virginia Union University, graduating in 1967. Robinson then entered Harvard University Law School but soon discovered that his life’s work would not include practicing law.

After my first year of law school, I all but knew that I would never practice law . . . . I knew early that I simply couldn’t endure the tedium of practice. I couldn’t make myself enjoy the numbing task of drafting coma-inducing legal briefs and then plodding through the even more deadly labyrinthine and dreary passageways of legal procedure

(Robinson, 1998:68)

Nonetheless, he graduated in 1970. His experiences at Harvard and living in the predominantly African American community of Roxbury had a profound effect on him. As a southerner, he had endured segregation, and knew what to expect from the whites he encountered, but Boston was in the North, and he had anticipated an integrated city. The racial strife that polarized the city in the sixties and seventies and its accompanying violence surprised and perplexed him.

Robinson became increasingly fascinated by Africa as he began to read more about the continent. He became interested in the liberation struggles of Angola, Mozambique, and Guinea-Bissau, and in 1970 he established the Southern Africa Relief Fund to provide military assistance to those who were struggling to end colonial and white minority rule, raising four thousand dollars. In addition, he became interested in U.S. foreign policy in Africa and its relationship to American multinational corporations. Robinson recalls in his autobiography that, “at the age of twenty-nine, I knew only that I wanted to apply my career energies to the empowerment and liberation of the African world” (Robinson, 69). He realized that black people throughout the world were in a similar situation; they suffered from the same legacies of slavery, colonialism, and racism. In Robinson’s view it was essential that the peoples of the black diaspora had a voice in the decisions that affected their daily lives.

Robinson’s sense of mission about the African continent was fulfilled in 1970 when he was given a Ford Foundation grant that allowed him to spend six months in Tanzania. Again he could not escape racism and discrimination, and he achieved a broader understanding of the effects of colonialism. When he attempted to rent a car he was informed by an East Indian clerk that he would have to pay a deposit and that no cars were available. He returned to his hotel room and telephoned the same business. This time, when the clerk heard an American accent, but did not see Robinson’s skin color, he was told that a car was available and that the deposit was much lower. Even in Tanzania, he could not escape his skin color, and he realized the economic impact of the East Indian community brought to that nation by the British, who dominated the private retail sector.

Upon his return to the United States in 1971, he practiced law for the Boston Legal Assistance Project and then worked as community organizer for the Roxbury Multi-Service Center. Robinson’s interest in Africa continued, and he organized the Pan African Liberation Committee to bring attention to American investment on the continent and its role in colonial liberation struggles. He devoted particular attention to the roles of his alma mater, Harvard University, and Gulf Oil in sustaining corrupt regimes in Africa and other parts of the third world. In 1975 Robinson moved to Washington, D.C., serving first as a staff assistant for Congressman William Clay and then as an administrative assistant for Congressman Charles Diggs. While working on Diggs’s staff, he visited South Africa in 1976 and gained a deeper understanding of the pernicious nature of that country’s apartheid system.

Two years later TransAfrica was established under Robinson’s leadership. The organization soon emerged as the leading African American advocacy group on issues affecting people of African descent: white minority rule in southern Africa, ethnic strife and war throughout the African continent, human rights violations, the plight of Haitian refugees, and the lack of economic, social, and political resources available to black people throughout the diaspora. Through Robinson’s leadership, people from various religious, ethnic, social, and economic backgrounds attempted to shape American foreign policy in Africa through a series of protests, marches, and demonstrations. Robinson believed that civil disobedience was important to draw national attention to the conditions of blacks living under apartheid. It was a mechanism to galvanize students, workers, intellectuals, politicians, celebrities, the young and old, blacks, whites, and others around a common issue. His ultimate goal was to convince Congress to pass economic sanctions against South Africa’s apartheid government. Others inspired by TransaAfrica constructed shantytowns on college campuses to protest their universities’ investment in apartheid South Africa. Though TransAfrica’s methods were much more confrontational, Robinson’s anti-apartheid efforts paralleled those of LEON SULLIVAN, who worked closely with American corporations to end investment in South Africa.

Robinson thought that it was important for college students to understand the role that university investments played in maintaining apartheid. He also believed that people should be conscious of how their governments and companies invested their money in South Africa, and he encouraged them to push for divestment. Robinson appeared on national television, before congressional committees, and wherever else he could, to encourage the U.S. government to change its policy toward South Africa by enforcing economic sanctions against the apartheid regime and to call for the end of white minority rule in Namibia. To further debate on such matters, he established the TransAfrica Forum in 1981, an organization that engages in outreach work for the African American community and the broader public by providing seminars and conferences to inform people about the impact of US foreign policy on Africa and its diaspora.

In 1986 Robinson’s hard work with the Congressional Black Caucus and other members of Congress resulted in the passage—over President Ronald Reagan’s veto—of the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act, which served to strengthen existing sanctions and urged a transition to democratic rule in South Africa. (Some Reagan administration officials felt a closer affinity to the anti-communist regime in Pretoria than to Nelson Mandela’s African National Congress, which included communists like Joe Slovo in leadership positions).

Robinson married Hazel Ross, who worked with him at TransAfrica, in 1987. They have one daughter, Khalea.

Although ending white minority rule in southern Africa was at the forefront of Robinson’s work, he continued to push for improved economic conditions in the Caribbean, better treatment of Haitian refugees by the U.S. government, and the removal of dictators in Africa. In addition, he spoke out against the human rights violations committed by Sani Abacha’s dictatorship in Nigeria and democratic failures in other African countries. He also called for reparations for blacks in the United States and was a vocal critic of the African Growth and Opportunity Act, passed by Congress in 2000 in an effort to move Africa-U.S. policy from aid to trade. His books include Defending the Spirit: A Black Life in America (1998), The Debt: What America Owes Blacks (2001), and The Reckoning: What Blacks Owe to Each Other (2002). These works, like Robinson’s life and career in general, have been dedicated to ensuring that American foreign policy makers address the issues, concerns, and needs of the African diaspora.

Robinson, Randall. Defending the Spirit: A Black Life in America (1998).

—CASSANDRA VENEY

ROBINSON, SUGAR RAY

ROBINSON, SUGAR RAY(3 May 1920?-12 Apr. 1988), world boxing champion, was born Walker Smith Jr. in Detroit, Michigan, the third child of Walker Smith, a laborer, and Leila Hurst, a seamstress. Robinson divided his youth between Detroit and Georgia and later moved to New York City. It was in Detroit that he was first exposed to boxing. As he recalls in his biography, Sugar Ray, he carried the bag of the future heavyweight champion of the world, Joe Louis Barrow, soon to be JOE LOUIS, to the local Brewster Street Gymnasium.

Smith adopted the name Ray Robinson quite unintentionally. When his manager, George Gainford, needed a flyweight to fill a slot in a boxing tournament in Kingston, New York, young Walker Smith was available. In order to box, however, he needed an Amateur Athletic Union identity card. The AAU card verified that participating boxers were not professionals. Gainford had a stack of cards and pulled one out with the name “Ray Robinson” on it. The real Ray Robinson no longer boxed for Gainford’s team, but the name stuck. The “Sugar” moniker was added later after Gainford, or perhaps a reporter or bystander (reports vary), declared that Ray was “as sweet as sugar.”

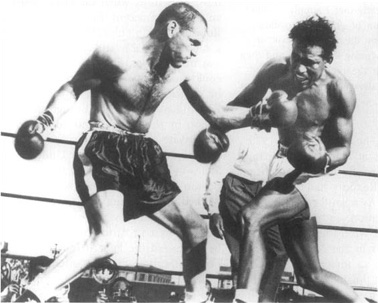

Sugar Ray Robinson boxing Bobo Olson in 1956 and regaining the middleweight championship of the world. Corbis

Robinson turned professional on 4 October 1940, after great success as an amateur, including winning the Golden Gloves featherweight title. He was also briefly married at this time to a woman named Marjorie. That marriage was annulled after a short period, though they had a son together named Ronnie. Robinson had two other marriages. The second, in 1943, was to Edna Mae Holly. They had a son named Ray Robinson Jr., born on 13 November 1949. Ray Sr.’s final marriage was to Millie Bruce.

In 1943 Robinson joined the U.S. Army, where he spent most of his time fighting in boxing exhibitions and renewed his relationship with Joe Louis. The two men were arrested on one occasion at a military camp in Alabama for refusing to use a segregated waiting area, but were later released.

Robinson held the world welterweight title from 1946 to 1951 and was then middleweight champion five times between 1951 and 1960. At his peak his record was 128–1–2 with 84 knockouts. He never took a ten-count in his 202 fights, though he once suffered a TKO. In Robinson’s day a boxer typically fought only eighty to one hundred bouts; today’s boxers fight far fewer contests. Such a punishing schedule and his advancing years finally took their toll; thirteen of his nineteen defeats occurred between 1960 and 1965, when he was in his forties and well past his prime.

One of the most poignant bouts in Robinson’s career was his June 24, 1947, fight with Jimmy Doyle in Cleveland, Ohio. A week before the fight Robinson dreamed that he had killed Doyle in the ring. He told his manager, “the kid dropped dead at my feet, George.” Robinson informed all who listened that he did not want to fight, fearing that the premonition would come true. In the end it did. Robinson knocked Doyle out in the eighth round of this fight, and Doyle never awakened.

Robinson’s most notable bouts were those against Jake LaMotta in the mid 1940s and early 1950s, when they battled each other a total of six times. Those fights and LaMotta’s life were intertwined with Robinson’s. With the exception of their first encounter, Robinson won all of these bouts, including his first world middleweight title on February 14, 1951. LaMotta’s life was memorialized in the Academy Award-winning motion picture Raging Bull.

Perhaps Robinson’s greatest boxing accomplishment was his success at a wide range of fighting weights. As an amateur he had been a featherweight, a division restricted to those weighing between 122 and 130 pounds, and began his professional career as a lightweight, where the fighting limit was 140 pounds. His first world championship victory came at the welterweight division (140–147 pounds) in December 1946, when he defeated Tommy Bell after fifteen bruising rounds in New York. In 1950 Robinson moved up to the middleweight division, where a fighter can weigh up to 160 pounds. It was at that weight that he defeated Jake LaMotta to win the world championship in 1951. In the late 1950s he even contemplated a bout with the then heavyweight champion of the world, Floyd Patterson. Though that bout never took place, press reports claimed that Robinson was offered one million dollars to take on a boxer who outweighed him by dozens of pounds.

Robinson did, however, challenge light heavyweight champion Joey Maxim. That bout was held in Madison Square Garden on 25 June 1952, which turned out to be one the hottest nights in fifty-three years. The temperature at ringside was 104 degrees. Although most of the scorers had Robinson ahead on points at the end of the bout, he lost when he passed out from exhaustion in the thirteenth round. In the tenth round the referee had to be relieved of his duties, as he was also on the verge of passing out from the heat.

Six months after the Maxim fight, Robinson announced his retirement and his intention of becoming a full-time entertainer. He developed a stage show that included tap dancing, singing, and telling jokes. He performed at venues including the French Casino in New York City as well as clubs on the French Riviera. For a variety of reasons, including the need for cash, Robinson reentered the ring three years later.

Beyond the ring and his boxing records, Robinson was responsible for a number of firsts. One of his little-mentioned contributions to sports is that Robinson was the first to have an official “entourage,” the precursor of the modern athlete’s posse. He first heard the word as he was disembarking from the cruise ship Liberté on a trip to France. When one of the porters asked whose trunks and suitcases were being unloaded, he was told that it was for Robinson’s “entourage.” Robinson used that term from then on. Perhaps because so many other boxers, notably Joe Louis, suffered financially at the hands of unscrupulous managers and agents, Robinson was deeply involved in the management of his boxing career, as well as his investments outside of the ring. Those outside investments included the ownership of a bar, a dry cleaning store, a barbershop, and a lingerie store in Harlem. He often negotiated his own boxing deals and was known for pulling out of agreements when he did not feel that promoters were adhering to the negotiated terms.

Robinson’s final moment of glory in the ring came on 10 December 1965. That night he formally retired from boxing before a crowd of 12,146 fans at Madison Square Garden. Four of his key lifetime opponents entered the ring before him. As Robinson entered to a standing ovation, he was lifted by his competitors and former challengers, Carmen Basilio, Gene Fullmer, Randy Turpin, and Carl “Bobo” Olson. Jake LaMotta, Robinson’s best-known opponent, was not invited, as he had thrown a fight in that very venue in 1957. Robinson closed out that evening with a speech where he said, “I’m not going to say goodbye. As they say in France, it’s a tout à l’heure—I’ll see you later.”

Following his second retirement from the ring, Robinson focused again on his entertainment career. He appeared in a number of motion pictures, notably The Detective (1968), starring Frank Sinatra, and Candy (1968), with Richard Burton and Marlon Brando. He was a regular on television, appearing on The Flip Wilson Show, among other variety programs, and on Mission Impossible, The Mod Squad, and Fantasy Island. He also focused much of his time and efforts on his Sugar Ray Youth Foundation, founded in 1969 and based in Los Angeles, California, and which provided the means for tens of thousands of children to participate in sports and other programs. One of its most distinguished alums was the Olympian and 100 meter dash world record holder FLORENCE GRIFFITH-JOYNER.

In his final years Robinson suffered from Alzheimer’s disease and curtailed almost all of his public appearances. His third wife, Millie, was constantly by his side at this stage. He died as a consequence of diabetes and Alzheimer’s in Culver City, California. The mourners at his funeral included boxers Archie Moore and Mike Tyson, as well as Elizabeth Taylor and Red Buttons. The Reverend JESSE JACKSON delivered the eulogy. Robinson is buried, in the company of numerous other celebrities, at Inglewood Cemetery in Ingle-wood, California.

Sugar Ray Robinson is best known as the greatest boxer, pound for pound, of all time, according to Ring magazine. During his life his presence extended beyond his boxing skills to showmanship, class, and grace. In 1999 the Associated Press named him both the greatest welterweight and greatest middleweight boxer of all time and ultimately named him the fighter of the century, just ahead of MUHAMMAD ALI.

Robinson, Sugar Ray, with Dave Anderson. Sugar Ray (1970).

Mylar, Thomas. Sugar Ray Robinson (1996).

Schoor, Gene. Sugar Ray Robinson (1951).

Obituary: New York Times, 13. Apr. 1989.

—KENNETH L. SHROPSHIRE

ROPER, MOSES

ROPER, MOSES(1815–?), fugitive slave, antislavery agitator, memoirist, and farmer, was born in Caswell County, North Carolina, the son of a white planter, Henry H. Roper, and his mixed-race (African and Indian) house slave, Nancy. Moses Roper’s light complexion and striking resemblance to his father proved embarrassing to the family. The animosity of the wife of his father, coupled with the death of Moses’s legal owner, probably a man named John Farley, led to Henry Roper’s decision to trade mother and son to a nearby plantation when Moses was six years of age. Soon after, he was sold to a “Negro Trader” and shipped south. He never saw his mother again. Over the next twelve years he was sold repeatedly in North and South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida.

Moses Roper’s white skin had an impact on his value on the slave market. Unable to secure a buyer, various slave traders found it necessary to hire the young boy out. Before the age of eleven, he worked first as a waiter and then as a tailor’s apprentice. When he was eleven, Roper was sold to a Dr. Jones, a planter from Georgia, beginning a remarkable period during which, by his own accounting, he was sold at least thirteen times. It was his last owner, John Gooch, a cotton planter from Kershaw (“Cashaw” in Roper’s narrative) County, South Carolina, who proved the worst. Gooch was a brutal man who flogged Roper unmercifully for minor offenses. Roper claimed that when Gooch was away on business, his wife stood in, whipping him with impunity. After repeated torture, the fourteen-year-old Roper could take no more and attempted to escape. He was soon captured near the Gooch plantation and harshly flogged. But this began a period during which Roper ran away whenever the opportunity presented itself. Once he made it as far as Charlotte, North Carolina, before being captured and returned to Gooch, who always stood ready to make his slave pay for the transgression.

In 1833 Roper’s life changed for the better when Gooch sold him to a northern Florida slave trader whose economic travails soon led to bankruptcy. To pay his debts, the trader sold Roper to a local planter with a reputation for extreme brutality. Rather than endure that abuse, Roper once again took to the roads and swamps, eventually making his way to Savannah, Georgia, where he convinced a sea captain to take him on as a steward. After a period of extreme anxiety for Roper, the ship set sail for New York.

Roper took advantage of an escape network along the eastern seaboard that historian David Cecelski has characterized as the “maritime underground railroad.” Coastal geography as well as demography made this region of the slaveholding South more porous than most. In North Carolina alone, blacks composed 45 percent of the population of the tidewater counties. Black watermen worked as stevedores, stewards, and pilots. Many lived and worked as squatters and swampers. Their world was the “underside of slavery,” where the institution was anything but stable. Their actions betrayed the “complex, tumultuous, and dissident undercurrent to coastal life in the slavery era” (Cecelski, “Shores of Freedom,” 176). Runaway slaves like Roper found a ready-made network of allies willing to assist them on their way northward. Roper estimated that he had traveled nearly five hundred miles to get to Savannah from Florida along the tangle of rivers and creeks that crisscross the region.

In August 1834 Roper arrived in New York City. His euphoria was short-lived, however, when he was informed that he could easily be recaptured. He continued up the Hudson River towards Poughkeepsie, New York, battling both a racist crew who claimed to know his true identity and a cholera outbreak that nearly killed him. Roper eventually journeyed into Vermont, securing work as a farmhand. Soon after his arrival, he was informed that he was being “advertised” in area newspapers. He fled Vermont for New Hampshire and after a short while went to that hotbed of abolitionist agitation, Boston, Massachusetts, where he made contact with local abolitionists, including William Lloyd Garrison. Roper’s name appears as one of the signatories of the constitution of the American Anti-Slavery Society. But even in Boston, life for a fugitive slave was precarious. After several weeks of working for a Brookline shopkeeper, Roper was told by two of his black neighbors that a “gentleman” had been inquiring for a person matching his description. He left Boston, hiding first in the Green Mountains and then making his way to New York City, where he was able to secure passage on a ship, the Napoleon, bound for England.

Roper arrived in Liverpool, England, in November 1835, armed with letters of recommendation to noted British abolitionists John Morrison, John Scoble, and George Thompson, who quickly embraced the young fugitive and pressed him into service as an antislavery lecturer. When Roper expressed an interest in getting an education, his patrons convinced Dr. Francis Cox to assume the financial burden for sending him to boarding school, first at Hackney and then at Wallingford. Roper also attended University College in London for a short while in 1836. All the while he continued lecturing to reform audiences across the country, becoming one of the first former slaves to play such a role.

In 1837 Roper published in London a narrative of his life as a slave, A Narrative of the Adventures and Escape of Moses Roper from American Slavery; it was published in the United States one year later. The publication was accompanied by an extensive lecture tour. In 1839 he married Ann Stephen Price, an Englishwoman from Bristol who assisted him in carrying on the antislavery work. In 1844, after nine years of lecturing, Roper estimated that he had given two thousand lectures. He informed the British Anti-Slavery Society that he was going to retire and asked that they assist him in putting together the funds to purchase a farm in the British colony on the Cape of Good Hope in southern Africa. There he hoped to put the agricultural knowledge that he had gleaned during his labors as a slave to better use. Roper never made it to Africa, but he did secure the capital to purchase a farm in western Canada. He returned to England twice, in 1846 to supervise another edition of his narrative, and in 1854 to lecture. Unfortunately, historians have been unable to determine how Roper spent the remainder of his life.

Given the intense suffering of Roper’s early years, his is a remarkable tale of resilience that ultimately illuminates the network that was the “maritime underground railroad.” If Roper is a minor character in the history of American slavery and abolitionism, it is important to note that he was also a key transatlantic connection in the early stages of an international movement to abolish slavery.

Roper, Moses. A Narrative of the Adventures and Escape of Moses Roper from American Slavery (1838; repr. in William L. Andrews, ed. North Carolina Slave Narratives [2003], 21–76).

Cecelski, David S. “The Shores of Freedom: The Maritime Underground Railroad in North Carolina, 1800–1861.” North Carolina Historical Review 71 (Apr. 1994).

_______. The Waterman’s Song: Slavery and Freedom in Maritime North Carolina (2001).

Ripley, C. Peter, et al., eds. The Black Abolitionist Papers. Vol. 1, The British Isles, 1830–1865 (1985).

—MARK ANDREW HUDDLE

ROSE, EDWARD

ROSE, EDWARD(?–1833?), mountain man and Indian interpreter, may have been born in Kentucky, near Louisville, most likely of African, Indian, and white ancestry. The year and date of his birth remain unknown, as do the names and occupations of his parents. It is possible that Rose was born a slave. The details of Rose’s life have been gleaned from the narratives and records of others, including Washington Irving, who claimed that after leaving home as a teenager, Rose became a kind of roving bandit, “one of the gangs of pirates who infested the islands of the Mississippi, plundering boats as they went up and down the river . . . waylaying travelers as they returned by land from New Orleans . . . plundering them of their money and effects, and often perpetuating the most atrocious murders” (Astoria, ch. 24). It appears that Rose left New Orleans after the police broke up his gang, eventually settling in St. Louis, where, in the spring of 1806, the local newspaper described him as big, strong, and hot-tempered, with a swarthy, fierce-looking face.

That same year Rose traveled up the Osage River with a group of hunters, after which he must have returned to St. Louis, because in the spring of 1807 he left from there with Manuel Lisa’s fur-trading expedition up the Missouri River, the first major expedition organized after Lewis and Clark’s return to St. Louis. Led by Lisa, a St. Louis businessman, the party traveled north, up the Missouri River through present-day North and South Dakota, and then southwest, along the Yellowstone River to the mouth of the Bighorn River, where they established the first trading post on the upper river, Fort Manuel (also called Fort Lisa), in what became Montana. After trading jewelry, tobacco, liquor, weapons, and blankets for pelts with the local Crow Indians (Absaroke or Sparrowhawk people), Lisa and his men returned to St. Louis. Rose, however, chose to remain behind. Living with the Crow in what is now southern Montana and northern Wyoming, Rose learned their culture and language. Because of his appearance, Rose was known as Nez Coupe (“Scarred Nose”) and later, after a particularly fierce battle, as Five Scalps.

It has been suggested that during this time Rose partnered with the French frontiersman and husband of Sacagawea, Toussaint Charbonneau, in escorting Arapaho women captured by Snake Indians to European trappers willing to pay for Indian women. In any event, in the spring of 1809 Rose joined an expedition organized for the purpose of escorting Sheheke (also known, by whites, as Big White), the principal chief of Matootonha, a lower Mandan village, through hostile territory back to his tribe. In 1806 Sheheke, along with his wife and children, had accompanied Lewis and Clark to St. Louis and Washington, D.C., via Monticello, where they met Thomas Jefferson. The first attempt to return Sheheke in 1807, led by Nathaniel Pryor, had failed because of resistance from the Sioux and Arikara. Two years later, with a contract for seven thousand dollars paid to the Missouri Fur Company by the U.S. government, twenty men, including Rose, spent three months traveling with the chief and his family northwest, up the Missouri River to Matootonch, in present-day North Dakota. On the way back to St. Louis, Rose elected to rejoin the Crow.

In 1811 Rose was hired by the “Asto-rians”—John Jacob Astor’s Pacific Fur Company—as a guide for the first expedition to the Pacific Ocean since Lewis and Clark had returned six years earlier. Led by Wilson Price Hunt, a merchant from New Jersey with no experience as a hunter or trapper, the party included sixty-four men and eighty-four horses. Rose joined the party on the plains near the Arikara villages just north of the present-day border between North and South Dakota and guided the expedition through Crow territory. Suspicious of his loyalty to the Crow, Hunt never trusted Rose. Predisposed to believe reports that Rose was organizing a mutiny, Hunt fired him as soon as the party reached the Black Hills of South Dakota, an error in judgment that contributed to many of the expedition’s failures. Immediately after dispatching Rose, in an indication of what lay ahead, Hunt and his group became lost as they tried to pass through mountains. A few days later Rose returned with several Crow and helped the party find a pass.

Washington Irving’s description of Rose in his 1836 book Astoria; or, Anecdotes of an Enterprise Beyond the Rocky Mountains must have been typical of attitudes toward Rose, whom Washington describes as “one of those anomalous beings found on the frontier, who seem to have neither kin nor country . . . and was, withal, a dogged, sullen, silent fellow, with a sinister aspect, and more of the savage than the civilized man in his appearance” (Astoria, ch. 22) “This fellow it appears,” Washington continues, “was one of those desperadoes of the frontiers, outlawed by their crimes, who combine the vices of civilized and savage life, and are ten times more barbarous than the Indians with whom they consort” (Astoria, ch. 24).

A year later, in 1812, Manuel Lisa found Rose living with the Ankaras and hired him as a scout. Rose, however, never it made it to their meeting place in New Orleans, having attached himself to an Omaha Indian woman, with whom he remained in her tribe until he was arrested for drinking and fighting and taken to St. Louis. Records show that Rose was released in 1813 by Superintendent of Indian Affairs William Clark, in exchange for Rose’s promise to stay out of Indian territory.

Historians are unsure of Rose’s activities in the following decade, until 10 March 1823, when he left St. Louis with one hundred men on the ill-fated trapping expedition of William Henry Ashley and Andrew Henry, owners of the Rocky Mountain Fur Company. From the outset Ashley dismissed Rose’s counsel against bartering for horses with the Arikara and against mooring company boats on the same side of the river as the tribe. More disastrously, Ashley ignored Rose’s warning of an impeding Arikara attack, and when the ambush came, the company’s losses were heavy. Attacks on the traders continued until Colonel Henry Leavenworth arrived from Fort Atkinson with two hundred fur traders, frontiersmen, and Lakota and Tankton warriors organized into a frontier militia known as the Missouri Legion. Rose was made an ensign, and the militia attacked the Arikara villages in August 1823. In his official report submitted to General Henry Atkinson and dated 20 October 1823, Leaven-worth singled out Rose: “I had not found anyone willing to go into those villages, except a man by the name of Rose . . . . He appeared to be a brave and enterprising man, and was well acquainted with those Indians. . . . He was with General Ashley when he was attacked. The Indians at that time called to him to take care of himself, before they fired upon General Ashley’s party” (quoted in Burton, 11).

Trying to salvage the expedition, Ashley assembled a small party of men, described by Harrison Clifford Dale in the Ashley-Smith Explorations (1941) as “the most significant group of continental explorers ever brought together.” This group included Rose and other such noted frontiersmen as James Clyman, David Jackson, William Sublette, Jim Bridger, Hugh Glass, and Thomas Fitzpatrick. Led by Jedediah Smith, the party traveled up the Grand River and through the Black Hills to the Rockies. From Clyman’s diary we learn that Rose’s familiarity with the Indian language and customs saved the party from disaster.

Rose served with Smith for the next two years, leaving in May 1825 to join a large treaty-making expedition up the Missouri under the command of General Atkinson and Major Benjamin O’Fallon. Forty men on horseback, under the command of a Lieutenant Armstrong, went with Rose by land; the rest traveled up the river in nine boats. The Yellowstone expedition, as it came to be known, succeeded in signing peace treaties with all the tribes of the river except the Blackfoot. Reports of the expedition by several authors delight in recounting Rose’s mythmaking adventures. A clerk whose expedition journal was published in 1929 in the North Dakota Historical Society Quarterly documented one oft-repeated tale of Rose’s heroics and skill: “Thursday 30 June. Rose, an interpreter, one of the party, we understand, covered himself with bushes and crawled into the gang of 11 Bulls [buffalo] and shot down 6 on the same ground before the others ran off.”

Much of the information we know about Rose comes from a biographical sketch of him that Captain Ruben Holmes, a member of the Atkinson-O’Fallon expedition, published in the St. Louis Beacon in 1828 (reprinted in the St. Louis Reveille in 1848). In “The Five Scalps” (1848), Holmes describes Rose’s confrontation with a band of six hundred hostile Crow warriors: “One foot was on the pile of muskets, to prevent the Indians from taking any from it . . . his eye gleamed with triumphant satisfaction. There was an expression about his mouth, slightly curved and compressed, and a little smiling at the curves, indicative of a delirium of delight—his eye, his mouth, the position of his head, and scars on his forehead and nose all united in forming a general expression, that, of itself, seemed to paralyze the nerves of every Indian before him.”

Rose apparently rejoined the Crow after the 1825 expedition, and nine years later he rode alongside them in their battles with the Blackfoot. “The old Negro,” Zenas Leonard wrote in his autobiography, Adventures of Zenas Leonard, Fur Trader (1839), “told them that if the red man was afraid to go among his enemy, he would show them that a black man was not.” Rose was one of first black frontiersmen to earn a wide reputation, preceding JIM BECKWOURTH, who was born around 1800, by a generation. Indeed, Beckwourth, who in his autobiography, The Life and Times of James P. Beckwourth (1856), called Rose “one of the best interpreters ever known in the whole Indian country,” may have claimed some of the older man’s exploits for himself.

When and how Rose—whom Harold Felton describes as “a mountain man’s mountain man, a trail blazer’s trail blazer” (vii)—died remains unknown. Legend has it that Rose, Hugh Glass, and a third mountain man named Menard were killed and scalped on the frozen Yellowstone River in the winter of 1832–1833 by a band of Arikaras hostile to the Crow. A site called Rose’s Grave is located at the junction of the Milk and Missouri rivers, on the Milk River near the Yellowstone River.

Burton, Art T. Black, Buckskin, and Blue: African American Scouts and Soldiers on the Western Frontier (1999).

Felton, Harold W. Edward Rose: Negro Trail Blazer (1967).

Irving, Washington. Astoria; or, Anecdotes of an Enterprise Beyond the Rocky Mountains (1836).

—LISA E. RIVO

ROSS, DIANA

ROSS, DIANA(26 Mar. 1944–), singer and actress, was born in Detroit, Michigan, the second of six children of Fred Ross, a college-educated factory worker, and Ernestine Moten. Although Fred and Ernestine had intended to name their daughter Diane, a clerical oversight at the hospital altered the name to Diana. She was known as Diane to family and close friends, and the use of this familiar name has remained an indicator throughout her life of those among her inner circle. The family lived in a black middle-class neighborhood where, as she ironed her family’s laundry, she could see from her window fifteen-year-old Smokey Robinson singing with his friends on his front porch (Taraborrelli, 36). When Ross turned fourteen the family moved to the Brewster projects, a low-income development that had not yet warranted the stigmatizing nomenclature of “ghetto” or “slum.” The Rosses had an affordable three-bedroom home and attended Olivet Baptist Church, where Ross sang in the junior choir with her siblings, while her parents sang in the adult choir.

Ross attended Cass Technical High School, an esteemed public school, where she registered high marks in cosmetology and dress design; upon graduating in 1962 she was voted the best dressed in her class. In high school many of Ross’s peers had begun singing at parties and on street corners. One of these groups, the Primes, would eventually become the Temptations—but in the meantime their manager wanted a sister group to complement their local performances. The manager began with his girlfriend’s husky-voiced sister, Florence Ballard, as the centerpiece; recruited two of her friends, Mary Wilson and Betty McGlown; and searched exhaustively for the final voice. Primes singer Paul Williams finally suggested Ross, and the Primettes—undaunted by McGlown’s leaving the group to get married—quickly established themselves on the Detroit scene, earning fifteen dollars a week in local clubs and signing a deal with LuPine records, with whom they recorded two singles that were never released. But BERRY GORDY JR. at Motown Records, heeding the advice of his young star in the making, Smokey Robinson, was ready on 15 January 1961 to sign the four women. (They had recruited Barbara Martin to replace McGlown.) Gordy renamed the group the Supremes and began processing them through the Motown Artists Development Department, where they were schooled in style, public speaking, and overall deportment.

Hardly an immediate success, the Supremes floundered for three years, one album, and eight mediocre singles, in addition to weathering the first of many personnel changes. Ballard briefly departed in 1962 to tour with the Marvelettes, and Martin quit in order to have a baby. Ross sang lead only about half the time, and, at that point, the Supremes were attempting to succeed as a trio that sang songs with four-part harmonies. They toured briefly in 1962 under the auspices of a Motown revue, but it was not until another tour in June 1964, when Motown released “Where Did Our Love Go?,” that the Supremes had their first number-one hit. Written by Lamont Dozier and Brian and Eddie Holland—three of Motown’s premier writers and producers—the single was the first of a string of hits that helped define the Motown sound as a successful crossover hybrid of gospel, rock and roll, rhythm and blues, and pop.

The Supremes made numerous television appearances, most often on the Ed Sullivan Show, where their glamorous evening gowns and dashing wigs projected an image of black womanhood rarely seen by white Americans. During the mid-1960s the Supremes could boast a yearly income of $250,000 each. Ross literally took center stage by this point, singing lead and prompting Gordy to change the group’s name to “Diana Ross and the Supremes.” By 1969 they had hit number one with eleven singles, registering about half a dozen in the pop music canon: “Baby Love” (1964), “Come See about Me” (1964), “Stop! In the Name of Love” (1965), “I Hear a Symphony” (1965), and “You Can’t Hurry Love” (1966). They finished the decade with their twelfth hit, the ironically titled “Someday We’ll Be Together”—almost nine years to the day after signing with Motown, on 14 January 1970. Ross left to pursue a solo career. The Supremes continued shuffling personnel for another seven years before disbanding in 1977, never again hitting number one.

Ross continued manufacturing hit after hit for Motown, starting with 1970’s “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough.” She would eventually score seven more number-one hits as a solo artist, first with Motown and then with RCA, with whom she signed in 1981 for twenty million dollars. But the most dynamic element of her career to develop in the 1970s was her acting. She landed the lead in the BILLIE HOLIDAY biopic Lady Sings the Blues (1972) and was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Actress. Her next project, the Motown-backed vehicle Mahogany (1975), attempted to capitalize on her superstar status. The film’s production was notoriously troubled, as rumors surfaced about Ross’s demanding personality and Gordy’s curious decision to direct the film himself. Mahogany garnered hardly any positive reviews, but Ross did gain another number-one hit from the soundtrack, “The Theme from Mahogany (Do You Know Where You’re Going To?).”

In 1978 she again compelled her critics to claim that she was overbearing—and her supporters to praise her business acumen—by purchasing the movie rights to the Broadway smash The Wiz and reworking the story so that she could play the lead of Dorothy. The ensemble cast of MICHAEL JACKSON, RICHARD PRYOR, and LENA HORNE was not nearly enough to salvage this African American retelling of The Wizard of Oz from more sternly negative reviews.

The 1970s were also tumultuous personally for Ross. In 1970 she married Robert Silberstein, a music manager, with whom she had three children (though the first, she later admitted, was fathered by Gordy). They divorced in 1975; two years later, Ross married an international businessman named Arne Naess Jr., with whom she had two more children, but they divorced in 2000. Musically, she seemed to fall into a rut, always staying even with the latest trend, as with her tepid disco tracks, rather than innovating, as she had with the Supremes earlier in her career. In 1989 she returned to Motown as both a performer and a director of the company. She continued releasing albums but seemed to drift further and further from mainstream pop success. Ross wrote her autobiography, Secrets of a Sparrow, in 1993.

Ross, Diana. Secrets of a Sparrow (1993).

Haskins, James. Diana Ross (1985).

Itkowitz, Leonore K. Diana Ross (1974). Taraborrelli, J. Randy. Call Her Miss Ross (1989).

—DAVID F. SMYDRA JR.

ROWAN, CARL THOMAS

ROWAN, CARL THOMAS(11 Aug. 1925–23 Sept. 2000), journalist, diplomat, and United States Information Agency director, was born in Ravenscroft, Tennessee. He was one of three children of Thomas David Rowan, a lumberyard worker with a fifth-grade education who had served in World War I, and Johnnie Bradford, a domestic worker with an eleventh grade education. When Rowan was an infant, his family left the dying coal-mining town of his birth to go to McMinnville, Tennessee, lured by its lumberyards, nurseries, and livery stables. But there, in the midst of the Great Depression, they remained mired in poverty. The elder Rowan sometimes found jobs stacking lumber at twenty-five cents an hour and, according to his son, probably never made more than three hundred dollars in a single year. Meanwhile his mother worked as a domestic, cleaning houses and doing the laundry of local white families.

The family lived in an old frame house along the Louisville and Nashville Railroad tracks; Carl and his siblings slept on a pallet on a wooden floor. In his 1991 autobiography, Breaking Barriers, Rowan recalled a traumatic incident in 1933 when he, at age eight, awakened to his sister’s screams after she had been bitten on the ear by a rat. “We had no electricity, no running water, and, for most of the time, no toothbrushes,” Rowan wrote in Breaking Barriers. “Toilet paper was a luxury we did not know when secondhand newspapers were good enough for our outhouse” (Breaking Barriers, 10). He also recalled staving off hunger by hunting for rabbit. “I survived the Depression eating fried rabbit, rabbits and dumplings, broiled rabbit, rabbit stew and a host of similar dishes made possible because Two-Shot Rowan so often came home with a rabbit or two draining blood down his pants leg,” he said, referring to his father (Breaking Barriers, 11).

Rowan credited his mother, who often praised his abilities, and Bessie Taylor Gwynn, a teacher in his segregated high school, for rescuing him from a life of poverty. They instilled in him a love of academics, and because blacks were not allowed to use the local library, Gwynn smuggled books out of the white library for Carl. “This frail looking woman, who could make sense of the writings of Shakespeare, Milton, Voltaire, and bring to life BOOKER T. WASHINGTON and W. E. B. DU BOIS, was a towering presence in our classrooms,” he once wrote. During forty-seven years of teaching, Gwynn also taught Rowan’s mother and siblings. Rowan praised her for immersing him in a “wonderful world of similes, metaphors, alliteration, hyperbole, and even onomatopoeia. She acquainted me with dactylic verse, with the meter and scan of ballads, and set me to believing that I could write sonnets as good as any ever penned by Shakespeare, or iambic pentameter that would put Alexander Pope to shame (Breaking Barriers, 31–32). Gwynn insisted that Rowan keep up with world affairs, so he became a delivery boy for the Chattanooga Times, which afforded him the opportunity to read the newspaper each day. “Tf you don’t read, you can’t write, and if you can’t write, you can stop dreaming,’ Miss Bessie told me. So I read whatever she told me to read and tried to remember what she insisted that I store away.”

Carl Rowan with President Johnson in 1964, after Rowan’s appointment as director of the United States Information Agency. © Bettmann/CORBIS

While a student at Tennessee State University, an historically black college in Nashville, Rowan, at age nineteen, became one of the first twenty African Americans commissioned as officers in the United States Navy during World War II. Rowan was the only African American in a unit of 335 sailors. With the assistance of the GI Bill, he went on to earn a college degree in Mathematics from Oberlin College in Ohio and a master’s degree in Journalism from the University of Minnesota. In 1950 he married Vivien Murphy, the college-educated daughter of a Norfolk Navy Yard worker. The couple had three children: Carl Jr., Jeffrey, and Barbara.

Rowan began his journalism career in 1948 as a copy editor at the Minneapolis Tribune, and in 1950 the paper hired him as one of only a handful of black, general assignment reporters in the country. While African Americans had worked on mainstream newspapers as far back as the Civil War, black reporters were still a rarity in the early 1950s. His first major assignment was a series of articles on African American life in the Deep South, for which he traveled six thousand miles in six weeks. Flying out of Nashville, he said, “I was shocked in 1951 to see signs on two airport chairs proclaiming: FOR COLORED PASSENGERS NOLY. I was even more shocked to see four airport toilets marked WHITE MEN, COLORED MEN, then WHITE LADIES, and the last inviting COLORED WOMEN.” For his series he garnered an award for best newspaper reporting by the Sidney Hillman Foundation, and the Minneapolis Junior Chamber of Commerce named him Outstanding Young Man of 1951. He also secured a book contract for his first book, South of Freedom (1953). He went on to cover the Supreme Court’s historic school desegregation ruling, Brown v. Board of Education (1954) and some of the other major civil rights battles of the fifties, including the Montgomery bus boycott, which formed the basis for his third book, Go South to Sorrow.