SMITH, JAMES McCUNE

SMITH, JAMES McCUNEBessie Smith: Empress of the Blues (Charly Records CDCD 1030).

The Bessie Smith Story (vols. 1–4, Columbia CL 855–858).

—GLENDA R. CARPIO

SMITH, JAMES McCUNE

SMITH, JAMES McCUNE(18 Apr. 1813–17 Nov. 1865), abolitionist and physician, was born in New York City, the son of slaves. All that is known of his parents is that his mother was, in his words, “a self-emancipated bondwoman.” His own liberty came on 4 July 1827, when the Emancipation Act of the state of New York officially freed its remaining slaves. Smith was fourteen at the time, a student at the Charles C. Andrews African Free School No. 2, and he described that day as a “real full-souled, full-voiced shouting for joy” that brought him from “the gloom of midnight” into “the joyful light of day.” He graduated with honors from the African Free School but was denied admission to Columbia College and Geneva, New York, medical schools because of his race. With assistance from black minister Peter Williams Jr., he entered the University of Glasgow, Scotland, in 1832 and earned his BA (1835), MA (1836), and MD (1837) degrees. He returned to the United States in 1838 as the first professionally trained black physician in the country.

Resettled in New York City, in 1838 or 1839 Smith married Malvina Barnet, with whom he was to have five children, and successfully established himself. He set up practice in Manhattan as a surgeon and general practitioner for both blacks and whites, became the staff physician for the New York Colored Orphan Asylum, and opened a pharmacy on West Broadway, one of the first in the country owned by a black.

Smith’s activities as a radical abolitionist and reformer, however, secured his reputation as one of the leading black intellectuals of the antebellum era. As soon as he returned to the United States, he became an active member of the American Anti-Slavery Society, which sought immediate abolition by convincing slaveholders through moral persuasion to renounce the sin of slavery and emancipate their slaves. By the late 1840s he had abandoned the policies of nonresistance and nonvoting set forth by William Lloyd Garrison and his followers in the society. Instead, Smith favored political abolitionism, which interpreted the U.S. Constitution as an antislavery document and advocated political and ultimately violent intervention to end slavery. In 1846 Smith championed the campaign for unrestricted black suffrage in New York State; that same year he became an associate and good friend of Gerrit Smith, a wealthy white abolitionist and philanthropist, and served as one of three black administrators for his friend’s donation of roughly fifty acres apiece to some three thousand New York blacks on a vast tract of land in the Adirondacks. He became affiliated with the Liberty Party in the late 1840s, which was devoted to immediate and unconditional emancipation, unrestricted suffrage for all men and women, and land reform. In 1855 he helped found the New York City Abolition Society, which was organized, as he put it, “to Abolish Slavery by means of the Constitution; or otherwise,” by which he meant violent intervention in the event that peaceful efforts failed (though there is no indication that he resorted to violence). When the Radical Abolition Party, the successor to the Liberty Party, nominated him for New York secretary of state in 1857, he became the first black in the country to run for a political office.

In his writings, Smith was a central force in helping to shape and give direction to the black abolition movement. He contributed frequently to the Weekly Anglo-African and the Anglo-African Magazine and wrote a semiregu-lar column for Frederick Douglass’ Paper under the pseudonym “Communipaw,” an Indian name that referred to a charmed and honored settlement in Jersey City, New Jersey, where blacks had played an important historic role. He also wrote the introduction to FREDERICK DOUGLASS’s 1855 autobiography, My Bondage and My Freedom, and he often expressed his wish that Douglass relocate his paper from Rochester to New York City. Douglass considered Smith the “foremost” black leader who had influenced his reform vision.

Smith’s writings focused primarily on black education and self-help, citizenship, and the fight against racism; these themes represented for him the most effective means through which to end slavery and effect full legal and civil rights. He was a lifelong opponent of attempts among whites to colonize blacks in Liberia and elsewhere and a harsh critic of black nationalists who, beginning in the 1850s, encouraged emigration to Haiti and West Africa rather than a continuation of the fight for citizenship and equal rights. Although he defended integration, he also encouraged blacks to establish their own presses, initiatives, and organizations. “It is emphatically our battle,” he wrote in 1855. “Others may aid and assist if they will, but the moving power rests with us.” His embrace of black self-reliance in the late 1840s paralleled his departure from the doctrines of Garrison and the American Anti-Slavery Society, which largely ignored black oppression in the North—even among abolitionists—by focusing on the evils of slavery in the South. Black education in particular, he concluded, led directly to self-reliance and moral uplift, and these values in turn provided the most powerful critique against racism. He called the schoolhouse the “great caste abolisher” and vowed to “fling whatever I have into the cause of colored children, that they may be better and more thoroughly taught than their parents are.”

The racist belief in the innate inferiority of blacks was for Smith the single greatest and most insidious obstacle to equality. In 1846 he became despondent over the racial “hate deeper than I had imagined” among the vast majority of whites. Fourteen years later he continued to lament that “our white countrymen do not know us”; “they are strangers to our characters, ignorant of our capacity, oblivious to our history.” He hoped his own distinguished career and writings would serve as both a role model for uneducated blacks and a powerful rebuttal against racist attacks. As a black physician, he was uniquely suited to combat the pseudoscientific theories of innate black inferiority. In two important and brilliantly argued essays—“Civilization” (1844) and “On the Fourteenth Query of Thomas Jefferson’s Notes on Virginia” (1859)—he incorporated his extensive knowledge of biology and anatomy to directly refute scientific arguments of the innate inferiority of blacks.

The driving force behind Smith’s reform vision and sustained hope for equality was his supreme “confidence in God, that firm reliance in the saving power of the Redeemer’s Love.” Much like other radical abolitionists such as Douglass and Gerrit Smith, he viewed the abolition movement and the Civil War in millennialist terms: slavery and black oppression were the most egregious of a plethora of sins ranging from tobacco and alcohol to apathy and laziness that needed to be abolished in order to pave the way for a sacred society governed by “Bible Politics,” as he envisioned God’s eventual reign on earth. He strove to follow his savior’s example by embracing the doctrine of “equal love to all mankind” and at the same time remaining humble before him. He likened himself to “a coral insect . . . loving to work beneath the tide in a superstructure, that some day when the labourer is long dead and forgotten, may rear itself above the waves and afford rest and habitation for the creatures of his Good, Good Father of All.” Following his death in Williamsburg, New York, from heart failure, his writings and memories remained a powerful source of inspiration, a “rest and habitation” to future generations of reformers.

The Gerrit Smith Papers, housed in the George Arents Research Library at Syracuse University and widely distributed on microfilm, include thirty letters from James McCune Smith to Gerrit Smith that contain valuable information. Frederick Douglass’ Paper contains more essays by Smith than any other contemporary publication.

Blight, David W. “In Search of Learning, Liberty, and Self Definition: James McCune Smith and the Ordeal of the Antebellum Black Intellectual,” Afro-Americans in New York Life and History 9, no. 2 (July 1985): 7–25.

Ripley, C. Peter, ed. The Black Abolitionist Papers, vols. 3–5 (1991).

—JOHN STAUFPER

SMITH, TOMMIE

SMITH, TOMMIE(6 June 1944–), Olympic track-and-field gold medalist and world record holder, was born in Clarksville, Texas, to James Richard, a sharecropper, and Dora Smith. Tommie, the seventh of twelve children, grew up on a farm where his family raised hogs and cows and picked cotton. Like many black Texans hoping to escape the misery of the Jim Crow South, the Smiths moved to the San Joaquin Valley of California and settled in Lemoore. There, Smith’s athletic track career began in the fourth grade, when he raced the fastest kid at his school, his older sister, Sallie, and won. He struggled academically but nonetheless decided in the sixth grade that he wanted to be a teacher. Recognizing the lack of attention given to his own learning difficulties, he hoped that he might serve students more effectively.

Smith grew rapidly as he entered his teenage years, and he excelled at a variety of sports. In ninth grade, by which time he was already six feet, two inches tall, he ran the 100-yard dash in only 9.9 seconds; cleared the high jump at 6 feet, 5 inches; and recorded 24 feet, 6 inches in the long jump. He improved his 100-yard-dash time in 1963, when he ran the sprint in 9.5 seconds and the 220-yard dash in 21.1 seconds. Most Valuable Athlete awards in basketball, football, and track and field during his sophomore, junior, and senior years of high school earned Smith an athletic scholarship for the three sports at San Jose State University. Smith majored in social science and teaching at San Jose State and was also enrolled in the Army Reserve Officers Training Corps.

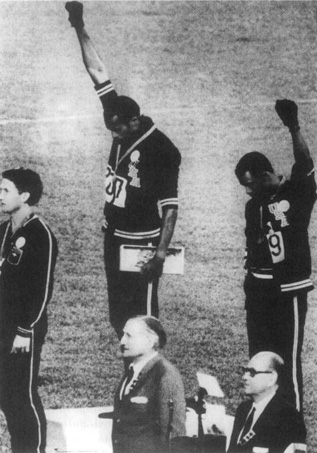

Tommie Smith (center) and John Carlos captured the world’s attention when they raised black-gloved hands and bowed their heads in protest against racism during the 1968 Olympic Games. Library of Congress

After attempting to compete as a three-sport athlete during his freshman year of college, he opted to focus on track and field for Coach Bud Winter. As a sophomore in 1965, Smith ran the 220-yard sprint in 20.0 seconds, tying the world record. Known for his powerful acceleration and for wearing dark sunglasses in his races, Smith soon emerged as a world-class sprinter and as a critical member of “Speed City,” the nickname given to San Jose’s track program. In 1966 Smith cut his 220-yard-dash time to 19.5, establishing a world record. He won the AAU and the NCAA titles in the 200-meter dash in 1967 and repeated his AAU title win the next year. Smith married the heptathlete Denise Paschal in 1967; their son, Kevin, was born in 1968.

That same year, Smith captured the world’s attention by raising his fist in a “black power” salute on the victory podium at the 1968 Mexico City Olympic Games. Smith’s actions took place during a time of turmoil on many college campuses as students protested the Vietnam War and demanded equality for women and racial minorities. African American athletes, both college and professional, became involved in these protests, while critics denounced collegiate athletic programs for exploiting African American athletes. At Smith’s college, San Jose State, the sociology instructor Harry Edwards encouraged black athletes to become politically active on campus and to fight for equality. Edwards established the Olympic Project for Human Rights and encouraged Smith and some of his teammates to consider the power of the platform that sport provided for the civil rights struggle.

In November 1967 Smith attended the Western Regional Black Youth Conference held in Los Angeles. At that conference Edwards organized a meeting of black collegiate athletes to discuss the possibility of boycotting the 1968 Olympic Games. Coming from a world-class sprinter, Smith’s declaration that he would support the boycott garnered significant attention. In an interview published in Life, Smith spoke of the difficulties African American students faced on predominantly white college campuses. Smith also addressed the need for athletic departments to hire black coaches and trainers in a Newsweek cover story, “The Angry Black Athlete.” He began to receive hate mail in response to his statements.

After much deliberation, Smith decided not to boycott the Olympics, but he was still the subject of great media scrutiny at the U.S. Olympic Trials hosted in Los Angeles. Smith qualified in his specialty, the 200 meters. With the threat of the boycott resolved, the International Olympic Committee’s (IOC) president, Avery Brundage, informed the black athletes who made the team that he would not tolerate any trouble. In the qualifying heats of the 200 meters, Smith wore tall black socks as his means of making a statement. He felt pain in his hamstrings but was determined to compete in the finals. On 16 October 1968 Tommie Smith won the gold medal in the 200 meters at the Olympic Games with a world-record time of 19.83 seconds. His San Jose State teammate John Carlos finished third.

Before the medal ceremony, Smith approached Carlos to discuss a nonviolent protest during the award ceremony. Smith wore a black glove on his right hand, with Carlos wearing the left glove. They each wore black socks with no shoes. As the American national anthem began to play, Smith and Carlos bowed their heads and raised their gloved fists in the air. The image was seen around the world, and the response was immediate. Some teammates were very supportive, while other American athletes criticized the use of the award platform as a place of protest. Others thought that sport was not the place for politics. Smith told the media that his raised fist with the black glove represented “black power” in America, and his black scarf represented black pride. His black socks with no shoes represented black poverty in racist America.

The U.S. Olympic Committee (USOC) did not want to make Smith and Carlos into martyrs, but they were pressured by Brundage and the IOC to punish the athletes. Smith and Carlos were suspended from the team, banned from the Olympic Village, and sent home. Brundage and the USOC warned the pair’s teammates that further protests would result in the same punishment. Even so, several black athletes expressed solidarity with Smith and Carlos. The 4 × 400–meter relay team wore black tams on the victory stand but did stand at attention during the national anthem. The long jumpers Bob Beamon and Ralph Boston, who won gold and bronze medals, respectively, wore black socks on the victory stand as a protest. Other teammates were less forgiving. Years later they remained critical, believing that the actions of Smith and Carlos reflected poorly on the entire team and overshadowed the accomplishments of the other members of the 1968 squad.

Following the Olympics, Smith returned to San Jose State for his final semester of college. Along with Carlos, he was both celebrated and denounced on campus for his black power protest; the ROTC even demanded that Smith return his military uniform. Smith graduated with a BA degree and later earned a master’s degree in Sociology from the Goodard-Cambridge Graduate Program for Social Change in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Upon graduation from San Jose State, Smith played football on the taxi squad of the Cincinnati Bengals, earning three hundred dollars a week. He recorded only one reception, for forty-one yards, in a professional game. Cut after the 1971 preseason, Smith played one month for the Hamilton Tiger-Cats of the Canadian Football League. Jack Scott, the radical athletic director at Oberlin College in Ohio, hired Smith in 1972 to coach track and field. Denied tenure at Oberlin in 1978, Smith relocated to California to coach the men’s track-and-field team at Santa Monica College. That same year, he married his second wife, Denise Kyle. They have three children, Danielle, Timothy, and Anthony.

Smith’s achievements on the track have left a lasting imprint on the record books. He is the only man to simultaneously hold eleven world records. His records of 10.1 seconds in the 100 meters, 19.83 seconds in the 200 meters, and 44.5 seconds in the 400 meters still rank high on the all-time lists. His 19.83 seconds in the 200 meters, set at the 1968 Olympic Games, stood until 1979 and was an Olympic record until 1984. He has received numerous honors for his athletic accomplishments, including induction into the National Track and Field Hall of Fame in 1978, the California Black Sports Hall of Fame in 1996, and the San Jose State University Sports Hall of Fame in 1999. Although they were once viewed as controversial and confrontational, the image of Tommie Smith and John Carlos giving the black power salute has come to be celebrated in recent years. San Jose State plans to erect a statue of the salute commemorating the two former student athletes.

Bass, Amy. Not the Triumph, but the Struggle: The 1968 Olympics and the Making of the Black Athlete (2002).

Edwards, Harry. The Revolt of the Black Athlete (1969).

Wiggins, David K. “‘The Year of Awakening’: Black Athletes, Racial Unrest and the Civil Rights Movement of 1968,” International Journal of the History of Sport 9 (1992).

—MAUREEN M. SMITH

SMITH, WILLIE MAE FORD

SMITH, WILLIE MAE FORD(23 June 1904–2 Feb. 1994), gospel singer and evangelist, was born Willie Mae Ford in Rolling Fork, Mississippi, to Clarence Ford, a railroad worker, and Mary Williams, a restaurateur. The seventh of fourteen children, Willie Mae had varying experiences in her early life as the family moved frequently throughout the Midwest. Clarence Ford worked hard to give his children a stable home. He and his wife were devout Christians whose interest in gospel singing extended beyond their music making in the home to area churches in and around Memphis, Tennessee, where the family moved shortly after Willie Mae’s birth.

The vibrant black community and musical environment of Memphis introduced Willie Mae to the two genres that would greatly influence both her musical development and the course of her life—blues and gospel singing. Willie Mae’s experience with the blues, considered by most Protestant blacks to be the “Devil’s music,” came in the form of singing blues songs on the streets of Memphis for money. Not unlike the Reverend Gary Davis and other early blues singers, Willie Mae would later claim that only through salvation in the church was she rescued from this life of sin. She overcame the moral reservations associated with the secular music genre and through the blues influence she developed the robust and resonating quality of her contralto voice. Willie Mae gained further experience in church, singing the long-meter hymns and spirituals that her mother enjoyed. As a small girl she was placed upon a table in the church, from this stage she enthralled her first audiences.

In 1917 the family settled in St. Louis, Missouri. Encouraged by her father, Willie Mae became the leader of a female quartet that included her sisters Mary, Emma, and Geneva. The Ford Sisters patterned themselves after popular male quartets of the day and earned a reputation throughout Missouri and Illinois. The group presented the “new” sound in gospel music—female groups that sang both a cappella and with piano accompaniment. The Ford Sisters reached a high point in their career when they performed at the National Baptist Convention in 1922. The National Baptist Convention was the largest body of black Protestants in America, the concerts that took place at these events influenced the latest trends in black gospel across the country. The Baptist musical tradition was quite conservative compared with those of Pentecostal and Holiness churches, but by 1922 the convention was just beginning to accept the new type of singing. The Ford Sisters’ reception at the convention was lukewarm, and despite efforts to keep the group functioning, domestic responsibilities proved more pressing than their desire to sing. By the mid-1920s the group had disbanded.

Willie Mae had discontinued her education after the eighth grade and was determined to become successful as a singer; therefore, she continued singing when her sisters could not, ultimately becoming a consummate soloist. In time, her reputation for soulful, spirit-filled performances earned her a place of distinction both in the St. Louis area and at the annual National Baptist Convention. There is uncertainty as to the date of her marriage; most sources cite either 1924 or 1929 as the year in which she married James Peter Smith, who owned a small moving company. The union produced two children, Willie James and Jacquelyn, who would often accompany their mother when she performed in and around St. Louis. When the Depression threatened James’s business, Willie Mae began traveling more widely, conducting musical revivals to supplement the family income.

On one of these occasions she met the gospel composer and former blues pianist THOMAS A. DORSEY. Impressed by Smith’s voice, Dorsey invited her to Chicago in 1932 to help organize the National Convention of Gospel Choirs and Conventions (NCGCC), which brought together directors and choirs from Baptist churches throughout the United States. Each year an annual convention was held in a different city, where new compositions were presented that directors could teach to their local choirs. Smith’s participation in the NCGCC placed her at the center of a musical movement that would diversify the marketing of gospel music and expand its audience beyond the traditional venues.

By 1936 her role in Dorsey’s gospel dynasty was secured when he appointed her the principal teacher of singing and the director of the soloist bureau of the convention. Smith’s devotion to the Dorsey convention did not, however, prevent her from performing on her own, and she continued to travel extensively throughout the late 1930s and early 1940s. In 1937 her performance at the National Baptist Convention of an original composition, “If You Just Keep Still,” gained her particular attention. From 1937 onward Smith spent a great deal of time on the road, while her husband raised their two children. She performed frequently in churches in Cincinnati, Buffalo, Detroit, Kansas City, Atlanta, and small towns around the Midwest and the South.

Her performance style changed considerably during the late 1930s and early 1940s when she joined the Church of God Apostolic, one of many Pentecostal denominations emerging during this period. She took on as accompanist a young woman named Bertha, whom she and James adopted. The combination of Smith’s robust voice and Bertha’s piano style was formidable and had a marked influence on the performance style of a number of gospel soloists and groups. Smith began to integrate into her performances elements of the singing styles of Sanctified churches, including rhythmic bounce, expressive timbres in the voice conveyed through melodic embellishments, slides, moans, groans, percussive attacks of words, phrases, and distinctive harmonies.

Central to Smith’s performance was her inclusion of sermonettes, five- to ten-minute sermons delivered before, after, and even during a song. The emotional quality of these sermonettes was intensified by her physical enactment of the text, though this, at times, brought the criticism of ministers and deacons who objected to her movements as undignified. Nevertheless, audiences packed the churches where Smith performed, and her popularity grew.

Although her live performances were highly successful, Smith never achieved the popularity that gospel recordings had helped her counterparts Roberta Martin and MAHALIA JACKSON attain. During the 1940s she concentrated on preaching and singing, openly acknowledging her “calling” to preach the gospel, though a woman preacher was not readily accepted in many black churches. Her career took a turn following the death of her husband in 1950. Soon afterward, Bertha grew disenchanted with traveling and eventually gave up her position as accompanist. Smith was never fully able to establish with other accompanists the musical rapport she had had with Bertha, and she began performing less frequently in order to devote more time to her domestic responsibilities.

“Mother Smith,” as she came to be known in congregational and church circles, began teaching gospel singing after the 1950s and mentored a number of noteworthy vocalists, including the O’Neal Twins, Edna Gallmon Cooke, and Brother Joe May, who reportedly was the first to call her “Mother.” In the 1970s she resurfaced to record several albums on the Savoy label and appear at the Newport Jazz Festival, and was featured in the 1982 film Say Amen, Somebody that solidified her place in gospel history. In 1988 she received the Heritage Award from the National Endowment of the Arts and a year later appeared in Brian Lanker’s book I Dream a World: Portraits of Black Women Who Changed America. On 2 February 1994, at the age of eighty-nine, Willie Mae Ford Smith died of congestive heart failure in a St. Louis nursing home.

Ford’s contribution to the gospel world was multifaceted. She defined the role of the female soloist at a time when gospel music was dominated by male quartets and groups. She effectively translated a blues-derived style into gospel singing and brought the regional traditions of St. Louis to national attention. More important to the gospel genre, perhaps, was her introduction of the sermonette and song format that became popular years later with the singers Shirley Caesar and Dorothy Norwood.

Boyer, Horace Clarence. How Sweet the Sound: The Golden Age of Gospel (1995).

Dargan, Thomas, and Kathy White Bullock. “Willie Mae Ford Smith of St. Louis: A Shaping Influence upon Black Gospel Singing Style,” Black Music Research Journal 9 (Fall 1989): 249–270.

Heilbut, Anthony. The Gospel Sound: Good News and Bad Times (1985).

Discography

Going on with the Spirit (Nashboro 7148).

I Believe I’ll Run On (Nashboro 7124).

The Legends: The O’Neal Twins, Thomas Dorsey, the Barrett Sisters, Sallie Martin, Willie Mae Ford Smith (Savoy SL-14742).

—TAMMY L. KERNODLE

STAGOLEE

STAGOLEE(16 Mar. 1865–11 Mar. 1912), the archetypal “bad man” of song, toast, and legend, was born Lee Shelton somewhere in Texas. Shortly after Shelton murdered William “Billy” Lyons in 1895, blues songs began to appear recounting the event, giving rise to the figure of Stagolee. Little is known about Shelton’s origins and childhood except the name of his father, Nat Shelton. The date of his birth is known only from his prison death certificate. The elegant style of his signature in his arrest records suggests that he had some schooling. Although he became the mythical Stagolee—a “bad mother” who shot somebody just to see him die—Lee Shelton was of ordinary stature. Prison records describe him as being five feet, seven and one-half inches tall. His hair and eyes are described as black, his “complexion” as “mulatto.” Under the column “marks and scars,” the authorities listed the following: “L[eft] eye crossed. 2 scars [on] R[ight] cheek. 2 scars [on] back head .1 scar on L[eft] shoulder blade” (Brown, 38).

The St. Louis Star-Sayings of 29 December 1895 refers to Lee Shelton as “Stag” Lee; the coroner’s report on Lyons calls him “Stack” Lee. The name “Stag” carries connotations of male sexual potency, but it also has associations with “Stagg Town,” which was widely used to refer to a black settlement or district, especially one characterized by poverty, crime, vice, and prostitution. Alternatively, or additionally, Shelton’s nickname may be related to that of the Stack Lee, a riverboat belonging to the Lee Line. Given the reputation of the riverboats for gambling, high living, and prostitution, this too has fitting connotations for Shelton. The trisyllabic versions of his name, spelled variously as Stagolee, Stagger Lee, Stackalee, Stackerlee, and Stack-o-lee, probably derive from the rhythmic requirements of the ragtime and blues in which the story was first couched.

In Gould’s St. Louis Directory for 1894, “Stack L. Shelton” is listed as a waiter living at 1314 Morgan Street. In 1897 he appears as “a driver,” living in a somewhat better neighborhood on North Twelfth Street. Some years later, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch called him “formerly a Negro politician” and said he was the “proprietor of a lid club for his race” (17 Mar. 1911). A “lid club” was an establishment that “kept a lid” on such criminal activities as gambling, while serving as a front for other illegal activities, including prostitution. At least until 1911, Shelton ran the Modern Horseshoe Club on Morgan Street, in the city’s red-light district. There is no reason to doubt that he ran the club as a gambling saloon, and its name certainly suits his profession as a driver. As a carriage driver, or “hack-driver,” Lee Shelton would have been able to direct both black and white male visitors to St. Louis to their choice of bordello. The most prestigious underworld nightclubs in “Deep Morgan” were the Chauffeurs Club, the Deluxe Club, the Jazzland Club, the Cardinal’s Nest, and the Modern Horseshoe. By the 1920s these were also the best blues clubs in the city. It is no wonder, then, that “Stagolee” is a blues song, since Lee Shelton was himself the owner of a famous blues café.

On Christmas night 1895, according to eyewitnesses, the extravagantly dressed Shelton entered the Bill Curtis Saloon on the corner of Morgan and Thirteenth Streets and asked, “Who’s treating?” Someone pointed out Billy Lyons, and the two drank and laughed together until an argument began, during which Shelton grabbed Lyons’s derby hat and broke the form. Lyons in turn grabbed Shelton’s hat—identified in many of the songs as a Stetson, the very symbol of masculinity. Shelton demanded his hat back, and Lyons refused. Shelton pulled his .44 revolver and hit Lyons on the head with it. According to an eyewitness, George McFaro, Lyons then pulled out a knife and taunted Shelton, “You cockeyed son of a bitch, I’m going to make you kill me.” Shelton backed off, took aim, and shot. He walked over to the dying Lyons, said, “Nigger, I told you to give me my hat,” snatched his hat, and walked out (Brown, 21–24).

The St. Louis Star-Sayings suggests that the killing may have been “the result of a vendetta” (29 Dec. 1895). Five years earlier a stepbrother of Lyons had killed a friend of Shelton’s. Further motivation may have arisen from the rivalry of various politically motivated “social clubs” organized ostensibly for the moral uplift of young black men. Shelton was leader of the recently formed Four Hundred Club, with Democratic Party ties, and Lyons had connections with a group led by Henry Bridgewater, a prominent black Republican and saloon owner. Motive, however, is not a problematic theme of the Stagolee blues; indeed, most versions focus on the mere taking of his hat as the catalyst that provokes Stag’s deadly reaction. Even the suggestion of the bluesman Mississippi John Hurt that it was a magic hat goes beyond the necessities of the mythical narration. The archetype of “badness” needs no deeper rationale.

Shelton was arrested at three o’clock on the morning of the 26th. By Friday, 27 December, he had hired a white lawyer, Nat Dryden, one of the best lawyers in St. Louis (although an alcoholic and an opium addict), and the first lawyer in Missouri to gain the conviction of a white man for murdering a black. At an inquest that day, Judge David Murphy signed a warrant against Shelton for first-degree murder. After being bound over to a grand jury on 3 January 1896, Shelton was released on a four-thousand-dollar bond, a considerable sum in 1896. The trial began on 15 July, during which Dryden argued that Shelton shot Lyons in self-defense. Three days later, after twenty-two hours of deliberation, the jury was unable to agree on a verdict. Shelton was again released on bond and apparently returned to running the Modern Horseshoe.

Nat Dryden died after a drinking binge in August 1897, before a second trial was held. There are no records of that second trial, but on 7 October 1897 Shelton began a twenty-five year sentence at the Missouri State Penitentiary. He was paroled on Thanksgiving Day 1909, but two years later he was in trouble again, “accused of robbing the home of William Akins, another Negro, last January, beating Akins on the head with a revolver and breaking his skull” (St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 17 Mar. 1911). Shelton was sentenced to five years and returned to prison on 7 May 1911. When he reentered prison, he was suffering from tuberculosis and his weight dropped to 102 pounds. Under pressure from other Democrats, Governor Herbert S. Hadley granted the weakened Shelton another parole; however, the Missouri attorney general objected, and Shelton died in the prison hospital on 11 March 1912.

But well before he died, Stagolee himself may have heard the song that gave rise to his mythic status. One version was collected in Memphis in 1903, and in 1911 hoboes were singing a version in Georgia. A circus performer heard it in the Indian Territory in 1913, at about the same time a white youngster hunting with his father heard Negroes singing it in Virginia’s Dismal Swamp. Indeed, the rapid spread of these songs exemplifies the workings of the oral tradition, and different details—the name of Shelton’s wife or girlfriend (Lilly or Nellie), the name of the judge, even the name of a bartender who witnessed the shooting—survive in different renditions. In evidence of its widespread popularity among black and white audiences, several jazz and dance orchestras, including Fred Waring’s Pennsylvanians, recorded versions in the early 1920s. In its opening stanzas, Mississippi John Hurt’s 1928 classic blues rendition captures perfectly the tone of the implacable heartlessness of its hero:

Police officer, how can it be?

You can arrest everybody but cruel Stagolee.

That bad man! O, cruel Stagolee.

Billy de Lyons told Stagolee, “Please don’t take my life,

I got two little babes and a darlin’ lovin’ wife.”

That bad man! O, cruel Stagolee.

“What I care about your two little babes, your darlin’ lovin’ wife?

You done stole my Stetson hat, I’m bound to take your life.”

That bad man! O, cruel Stagolee.

“Stagolee” became a staple of the blues repertoire and has been recorded by over two hundred musicians in styles ranging from blues to jazz, R&B, and rock and roll, including versions by MA RAINEY (1925), DUKE ELLINGTON (1927), CAB CALLOWAY (1931), BIG BILL BROONZY (1946), SIDNEY BECHET (1946), Lloyd Price (1959), JAMES BROWN (1967), the Clash (1979), and Bob Dylan (1993). In the Jim Crow atmosphere of the early twentieth century, Stagolee became a trope for the resentment felt by people marginalized by the dominant white society. For over a century, Stagolee has remained a symbol of rebellion—oppositional, subversive, underground, and largely invisible—as part of the unofficial subculture of prostitutes, gamblers, criminals, and other “undesirables” (Brown, 120). The tale is variously told, but the character of Stagolee continues to exemplify what it is to be “bad,” whether “bad” is meant as a compliment or an insult.

Barlow, William. Looking Up at Down: The Emergence of Blues Culture (1989).

Brown, Cecil. Stagolee Shot Billy (2003).

—CECIL BROWN

—JOHN K. BOLLARD

STAUPERS, MABEL DOYLE KEATON

STAUPERS, MABEL DOYLE KEATON(27 Feb. 1890–30 Sept. 1989), National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses executive officer, was born Mabel Doyle in Barbados, British West Indies, to Thomas and Pauline Doyle. In 1903 her family settled in Harlem, where her father became a brake inspector for the New York Central Railroad. Staupers attended public schools in New York and graduated from Freedmen’s Hospital School of Nursing (now the Howard University College of Nursing) in Washington, D.C., in 1917. After graduation, she began her professional career as a private-duty nurse in New York, but she soon went to work as a nurse administrator in Philadelphia. In 1922 she returned to Harlem and began an illustrious career as a nurse and an administrator.

The Great Migration of African Americans from the rural South resulted in an increase of over 66 percent in Harlem’s black population between 1910 and 1920. The attendant social problems of such rapid population change—inadequate housing, unemployment, and insufficient public health services—made Harlem a center for reform-related activism. Staupers, on behalf of the New York Tuberculosis and Health Association, undertook to survey the Harlem community to determine its public health needs. As a consequence of her final report, the Harlem Committee of the New York Tuberculosis and Health Association was created. Staupers served as its executive secretary for twelve years, during which time the Harlem Committee helped to create the city’s first hospital for black tuberculosis patients and initiated a public health library and a variety of programs for children, adults, physicians, nurses, and social workers. By the late 1920s the committee had duplicated many of these programs and their publications in Spanish. Staupers’s work with the Harlem Committee undoubtedly established her as an important person in the area of public health, but it was through her role as executive secretary and president of the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses that she achieved a national reputation. The NACGN was founded in 1908 in New York City, and Staupers joined in 1916 while she was still a nursing student. During its early years the organization’s leaders worked to improve and standardize nursing instruction and to raise the status of black nurses. After Staupers became executive secretary in 1934, the organization expanded, growing in membership from 175 to 821 by 1939. The NACGN was especially effective in its efforts to integrate the nursing profession, to improve black public health, and to cultivate leadership ability among black nurses while creating leadership roles for them. To reach these goals, Staupers and Estelle Massey Riddle Osborne, the NACGN’s first president, gained financial support from the Rosenwald Foundation, the General Education Board, and other sympathetic people and organizations. These funds enabled nurses to conduct regional and national conferences, to publish and circulate papers and reports, and to serve as a liaison between black nurses and the agencies and institutions that trained, employed, and promoted them.

An important goal for Staupers and other black nursing leaders was the complete integration of the American Nurses Association, for without full membership in the ANA no nurse could consider herself fully credentialed. Reaching this goal was no small accomplishment. ANA membership was gained either through state associations or through alumnae associations, yet most black nurses lived and worked in states that would not allow them to join, and the only black institution that had affiliate status with the ANA was Freedmen’s Hospital Nursing School.

Staupers and her colleagues undertook a variety of steps to open the ANA to black nurses. In 1938, for example, she helped create the NACGN Advisory Council, composed of representatives of the major nursing and public health organizations and a variety of private philanthropic agencies and public institutions. This council became a vehicle for pressuring the white national organizations to open their doors to black members. Estelle Osborne recommended that in the South, where state laws precluded the formal association of black and white nurses, the ANA should recognize the black organization as an ANA affiliate. In the North a different strategy was required. Large numbers of black nurses in the North had graduated from southern schools and had migrated from states that excluded them from membership in the state affiliate. At the least, an “individual membership” category was necessary. Staupers began the effort to establish this new category in New York, with the hope that if the New York State affiliate opened its membership to black nurses, other northern states would follow suit. But before the ANA was integrated, World War II began, and the campaign to integrate nursing spread to a new front.

Although the war created an increased need for nurses, neither the army nor the navy accepted black nurses. The armed forces took their nurses from among American Red Cross Nursing Service applicants, so Staupers encouraged black nurses to submit Red Cross applications. She also coordinated a campaign to pressure the military to change its policy. When the War Department decided in 1941 to accept a maximum of fifty-six black nurses at segregated military camps, Staupers coordinated a massive protest movement. By 1944 there were almost three hundred black army nurses, but the army still had a quota, and the navy still had no black nurses. Staupers wrote letters to military leaders on behalf of the NACGN, and she sent news releases to black newspapers publicizing the government’s discriminatory policy. She lobbied the surgeon general of the army and worked to persuade members of Congress to pass bills explicitly prohibiting racial discrimination “in the selection, induction, voluntary recruitment, and commissioning of nurses” in the armed forces.

In the fall of 1944 Staupers met with President Franklin D. Roosevelt to detail the problems arising from the quota on black nurses in the army, the segregation of the camps in which they worked, and their work assignments, which were usually limited to caring for German prisoners of war. When the surgeon general of the army announced in early 1945 that a special draft for nurses might be necessary, Staupers was present and asked why they did not accept the black nurses who were willing to serve. She also helped coordinate a successful letter-writing and telegram campaign protesting proposed amendments to the Selective Service Act that would have allowed the drafting of nurses. Within two months Staupers’s efforts had paid off. The army eliminated its quota for black nurses, and shortly thereafter the navy announced a “color-blind” recruitment policy.

During the war Staupers and members of the NACGN Advisory Council continued to put pressure on the ANA, and in 1942, following the example of the American Red Cross and the National League of Nursing Education, the ANA began to admit black nurses through their membership in the NACGN. Emboldened by the 1945 change in military policy, in January 1946 Staupers asked the ANA to directly admit black nurses from any state that denied them membership on the basis of race. The ANA agreed in September to admit qualified black nurses to the organization and its state affiliates. Although this process was not complete until 1948, Staupers considered her work done and stepped down as executive secretary of the NACGN.

The historian Darlene Clark Hine has written that it is likely that “the complete integration of black women into American nursing on all levels” would not have occurred without the work of Mabel Staupers” (Hine, 186). And, indeed, Staupers seemed indefatigable. Her work during the 1920s and early 1930s was critical to the creation of public health policies and programs in New York City. The historian Susan L. Smith notes that Staupers also was instrumental in establishing and organizing National Negro Health Week. She was a master coalition builder, linking black nurses and their organizations to other nursing groups and to philanthropic, government, civic, and social leaders throughout the country. She became the NACGN’s last president in 1949 and led the process of folding the goals and objectives of the NACGN into the ANA.

Although the NACGN ceased to exist in 1951, Staupers continued to encourage black nurses to protect the gains they had made and to submit histories of black nurses to the Schomburg Collection for Research in Black Culture of the New York Public Library. Ten years later she would publish her own history of the NACGN, No Time for Prejudice: The Story of the Integration of Negroes in Nursing in the United States (1961). In one of her final acts as president of the NACGN, Staupers encouraged her members to participate in the profession in ways to make real the new policy of integration. On 15 March 1951 the headquarters of the NCAGN closed; the ANA was finally a fully integrated professional organization for nurses. She died in Washington, D.C.

Although the NAACP awarded Staupers its prestigious Spingarn Medal in 1951 for her work in integrating the nursing profession, she did not “retire” from the profession after finishing her work as president of the NACGN. Almost immediately, she became a member of the Board of Directors for the ANA. Staupers remained active in the national black nursing sorority, Chi Eta Phi, and she received many honors for her life’s work from universities, church groups, nursing organizations, and civic associations.

Information on Staupers can be gleaned from the Mabel Keaton Staupers Papers in the Howard University-Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Washington, D.C., and from the Mabel Keaton Staupers Papers, housed at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture of the New York Public Library.

Hine, Darlene Clark. Black Women in White: Racial Conflict and Cooperation in the Nursing Profession, 1890–1950 (1989).

Shaw, Stephanie J. What a Woman Ought to Be and to Do: Black Professional Women Workers during the Jim Crow Era (1996).

Smith, Susan L. Sick and Tired of Being Sick and Tired: Black Women’s Health Activism in America, 1890–1950 (1995).

Obituary: New York Times, 6 Oct. 1989.

—STEPHANIE J. SHAW

STEWARD, AUSTIN

STEWARD, AUSTIN(1793–1865), antislavery reformer, was born in Virginia, the son of Robert Steward and Susan (maiden name unknown), slaves. About 1800 a well-to-do planter, William Helm, purchased the family. Escaping business reverses and debts, Helm moved to Sodus Bay on New York’s Lake Ontario frontier and shortly thereafter, in 1803, to Bath, New York, taking young Austin with him. Hired out for wages, Steward entered the employ of a Mr. Tower in Lyons, New York, where he worked until 1812. Escaping, he went to Canandaigua, where he worked for local farmers and attended an academy in Farmington. While thus employed, Steward learned of New York’s 1785 law banning the sale of slaves brought into the state subsequent to that date. Drawing upon the state’s 1799 gradual emancipation statute as well as an 1800 court decision, Fisher v. Fisher, which ruled that hiring out a slave constituted an intentional and fraudulent violation of the 1785 law, he openly asserted his freedom and continued to hire his labor in his own name, despite challenges from Helm.

Sometime between 1817 and 1820 Steward moved to Rochester. In 1825 he married a Miss B. of Rochester, the youngest daughter of a close friend, who bore him eight children, and, overcoming white opposition, he ran a successful grocery business. During these prosperous years, Steward became an activist on behalf of other northern blacks, both de jure and de facto free, who were subject to prejudice and treated as second-class citizens. From 1827 to 1829 he was an agent for Freedom’s Journal and the Rights of All, both black newspapers. In 1830 he served as vice president of the first Annual Convention for the Improvement of Colored People, held in Philadelphia.

Steward and his family moved to Upper Canada (now western Ontario) in 1831, where they joined a group of African Americans who had fled Cincinnati after the race riots of 1829. There they had established, under the leadership of their agent Israel Lewis, an organized black community called Wilberforce. Steward invested the savings from his grocery in the project and undertook a major role in its proceedings, replacing Lewis as its principal leader until the community collapsed six years later. His career there, however, was beset with ill fortune. He soon fought with Lewis over the handling of the community’s finances and other matters until in 1836 Lewis was dropped as the community’s principal agent. The brothers Benjamin Paul and Nathaniel Paul, who replaced him, proved equally unsatisfactory, the latter, who was sent to England to raise funds, never rendering a satisfactory account of his mission. By 1837 Wilberforce, wracked by internal dissension, had virtually ceased to exist, and Steward, his savings gone and his reform efforts blasted, returned to Rochester with his family.

Reestablishing himself in the grocery business, Steward prospered for a season, but the aftershocks of the 1837 panic and a disastrous fire finally destroyed the enterprise. Steward moved back to Canandaigua about 1842, where he taught school and continued his anti-slavery work as an agent for the National Anti-Slavery Standard. Although he gradually faded into obscurity, he was active for a while in the emerging political antislavery movement. He served as president of the New York Convention of Colored Men in 1840, 1841, and 1845 and lobbied for black male suffrage on equal terms as white suffrage.

Steward, like most other black activists, remained on the periphery of the antislavery movement, whose inner circles kept even noted abolitionist FREDERICK DOUGLASS at a distance. Moreover, by the 1840s Steward, tainted by his association with the failed Canadian settlement and lacking a personal following, was pushed from the black national convention limelight by younger, more aggressive black leaders such as HENRY HIGHLAND GARNET, JAMES MCCUNE SMITH, and Charles B. Ray.

Steward is best remembered for his autobiography, Twenty-Two Years a Slave and Forty Years a Freeman, published in 1857. It provides only a sketchy outline of his life and addresses his understanding of the evils of slavery, but it testifies primarily to the vicissitudes that African Americans experienced even in the North in its depiction of the struggle of one exceptional black man against social and economic discrimination and exclusion from the full political and legal privileges that white citizens enjoyed.

Steward pressed to achieve full citizenship for himself and others like him. For example, he attempted, unsuccessfully, to enlist in the Steuben County militia during the War of 1812, embraced the popular temperance reform of the 1830s, and served a term as clerk of Biddulph Township during his years in Canada. In the end, however, he always remained a marginal figure. His autobiography was his most effective undertaking; his strongest message was a plea to “those who have the power” to “have the magnanimity to strike off the chains from the enslaved, and bid him stand up, a Freeman and a Brother!” He died in Rochester, New York.

Steward, Austin. Twenty-Two Years a Slave and Forty Years a Freeman (1857), reprinted with an introduction by Graham Russell Hodges (2002); reprinted with an introduction by Jane H. Pease and William H. Pease (1969).

Pease, Jane H., and William H. Pease. Black Utopia: Negro Communal Experiments in America (1963).

_______. They Who Would Be Free: Blacks’ Search for Freedom, 1830–1861 (1974; repr. 1990).

Ripley, C. Peter, ed. The Black Abolitionist Papers, vol. 3 (5 vols., 1985–1992).

Winks, Robin. The Blacks in Canada (1971).

—WILLIAM H. PEASE

—JANE H. PEASE

STEWARD, THEOPHILUS GOULD

STEWARD, THEOPHILUS GOULD(17 Apr. 1843–11 Jan. 1924), author, clergyman, and educator, was born in Gouldtown, New Jersey, the son of James Steward, a mechanic who had fled to Gouldtown as an indentured child servant, and Rebecca Gould, a descendant of the seventeenth-century proprietor of West Jersey, John Fenwick. His family’s interest in history and literature supplemented his elementary school education in Bridgeton, and his mother encouraged him to challenge “established truths.” He began preaching in 1862, was licensed to preach by the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church in 1863, and was appointed to serve a congregation in South Camden, New Jersey, in 1864.

In May 1865 Steward accompanied AME bishop DANIEL ALEXANDER PAYNE and others on a mission to South Carolina, where they reestablished the denomination, which had been banned from the state after the DENMARK VESEY slave rebellion conspiracy of 1822. From 1865 to 1868 Steward nurtured new AME congregations in South Carolina. In 1866 he married Elizabeth Gadsden; before her death in 1893, they had eight children.

From 1868 to 1871 Steward was the pastor of the AME congregation in Macon, Georgia, which was later renamed Steward Chapel AME Church in his honor. From his base in Macon, Steward actively participated in the business and politics of Reconstruction. He worked as a cashier for the Freedmen’s Bank in Macon and speculated in cotton futures. He helped to write the platform of Georgia’s Republican Party in 1868 and served as an election registrar in Stewart County, Georgia. He organized a successful protest by freed slaves in Americus, Georgia, against compulsory labor contracts and attacked the practice of limiting jury service to white males.

Leaving Georgia in 1871, Steward spent the next twenty years as the pastor of AME congregations in Brooklyn, New York; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Wilmington, Delaware; and Washington, D.C. In 1873 he undertook a mission to Haiti, establishing an AME congregation in Port-au-Prince, and in 1877 he completed his first book, Memoirs of Mrs. Rebecca Steward (1877). From 1878 to 1880 he studied at Philadelphia’s Protestant Episcopal Church Divinity School.

In the subsequent decade, Steward published two theological works, Genesis Re-read (1885) and The End of the World (1888). In these two books, he undertook Christian reinterpretations of the first and the last things—the doctrines of creation and of the eschaton. Genesis Re-read offered a liberal evangelical’s assimilation of Darwinian evolutionary theory into Christian doctrine by arguing that evolution took place within a divine plan. The End of the World contested Anglo-Saxon triumphalism by contending that a final clash of nations would purge Christianity of its bondage to racism and give birth to “new nations,” borne out of darkness to walk “in the light of the one great God, with whom there are no superior races and no inferior races.”

Defeated in a bid for the presidency of the AME denomination’s Wilberforce University in 1884 and at odds with its bishops because of repeated challenges to their authority, Steward won an appointment as chaplain to the Twenty-fifth U.S. Colored Infantry Regiment in 1891. His wife died in 1893, and three years later, in 1896, he married Susan Maria Smith McKinney, a widow and physician; they had no children. After service at Fort Missoula, Montana, and Chickamauga, Georgia, Steward and his regiment were sent to Cuba in 1898 at the beginning of the Spanish-American War. On his return to Brooklyn later that year, he addressed a celebration of the war’s conclusion.

Steward wrote a novel, A Charleston Love Story, in 1899, but his main interest was military history. In addition to two pamphlets, Active Service; or, Gospel Work among the U.S. Soldiers (1897) and How the Black St. Domingo Legion Saved the Patriot Army in the Siege of Savannah in 1779 (1899), he published The Colored Regulars in the U.S. Army (1899), a vindication of the service of African American soldiers in the Spanish-American War.

Sent to the Philippines in 1900, Steward was stationed in Manila, where he served as superintendent of schools for Luzon province. In 1902 he was transferred back to the United States with the Twenty-fifth Infantry Regiment and stationed at Fort Niobrara, Nebraska, and Fort Brown near Brownsville, Texas. In August 1906 white residents reported that soldiers from Steward’s regiment had briefly roamed through Brownsville’s streets, freely shooting up its cafes and dance halls, killing a civilian and injuring a police officer. The soldiers maintained their innocence and implicated no one, but President Theodore Roosevelt dismissed them from service without honor and barred them from future government service. Steward, who had retired from the army in 1907, did not join in the African American community’s outcry against Roosevelt’s arbitrary action. But in his autobiography he wrote, “I have yet to find one officer who was connected with that regiment who expresses the belief that our men were guilty.”

In 1907 Theophilus and Susan Steward moved to Ohio, where he became vice president, chaplain, and professor of French, history, and logic and she became the college physician at Wilberforce University. Active in fundraising efforts for Wilberforce, Theophilus Steward advocated military training for African American men as preparatory to their struggle for freedom. In 1911 the Stewards were the AME delegates to London’s Universal Races Congress.

An active contributor to such newspapers as the Cleveland Gazette and the Indianapolis Freeman, Steward returned to familiar territory in his last books: family history in Gouldtown, a Very Remarkable Settlement of Ancient Date (1913), and military history in The Haitian Revolution, 1791 to 1804 (1914). He published his autobiography, From 1864 to 1914: Fifty Years in the Gospel Ministry, in 1921.

Steward’s papers are at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture of the New York Public Library.

Miller, Albert George. Elevating the Race: Theophilus G. Steward, Black Theology, and the Making of an African American Civil Religion, 1865–1924 (2003).

Seraile, William. Voice of Dissent: Theophilus Gould Steward (1843–1924) and Black America (1991).

—RALPH E. LUKER

STEWART, MARIA W.

STEWART, MARIA W.(1803–Dec. 1879), political activist, lecturer, evangelical writer, and autobiographer, was born Maria Miller in Hartford, Connecticut, where she was orphaned by age five. Nothing is known about her parents. As a five-year-old girl, she was “bound out,” or indentured, to a clergy family for ten years. She then moved to Boston, Massachusetts, where she supported herself as a domestic for the next ten years. Maria enjoyed no formal education but struggled through her youth and young adulthood to become literate and to gain an education. Until she was twenty years old, she attended Sabbath school classes, where she learned to read the Bible, and this served as a staple in her pursuit of learning.

Miller married James W. Stewart on 10 August 1826 in the Reverend Thomas Paul’s African Baptist Church in Boston. In addition to taking his last name, Maria adopted Stewart’s middle initial “W.” The couple become involved in Boston’s small, but growing black middle-class community, and like many of their entrepreneurial neighbors, they enjoyed financial security. James Stewart was a successful and independent shipping outfitter, whose business was situated in prime wharf space. Considerably older than Maria, he was, according to her witnessed claim for his service pension, “a tolerably stout well built man; a light, bright mulatto” (Richardson, 117). There was even a suggestion that his business peers thought him to be white until he married Maria, after which time he was listed as a black businessman.

Nevertheless, the Stewarts were not content with their own success and earnestly took up the cause of slaves and poor blacks. The political writer and activist DAVID WALKER, cofounder of the Massachusetts General Colored Association, one of the first avowedly black political organizations in the country, had a profound impact on the couple and on Maria especially. Walker’s 1829 work, Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World, one of the most influential black political documents of the nineteenth century, exposed the inhuman treatment of African Americans in general and slaves in particular, and responded directly to the racist sentiments espoused by Thomas Jefferson in his 1826 Notes on the State of Virginia, which stated in part that blacks were descended “from the tribes of Monkeys or Orang-Outanges.”

As owner of a “slop shop,” or used-clothing shop, Walker was able to distribute his pamphlet to every port along the Eastern Seaboard, the Caribbean, and other international ports in which the sailors docked, by planting his pamphlet in the pockets of clothing that he sold to mariners. Walker befriended James and Maria and used James’s contacts, as the only black businessman in his trade, to distribute his pamphlet more widely, which he did by hiding the text in the folds of sails and in ship fittings.

Walker died in 1830, apparently of consumption, although rumors still persist that he was poisoned. James W. Stewart had died a year earlier. The two deaths were tremendously difficult for Maria Stewart and were exacerbated by the probate court’s rejection of her husband’s last will and testament. As a result, she lost all rights and property interest in her husband’s estate and was left widowed and poor. This period of turmoil and grief pressed Stewart to reconsider her faith, and by 1831 she had publicly professed her faith in Christ.

This epiphany marked a new, active, and strident commitment to political action. She became a “warrior” and an advocate for “oppressed Africa.” Her essay “Religion and the Pure Principles of Morality, the Sure Foundation on Which We Must Build” (1831) became the first political manifesto authored and published by an African American woman. While she does not advocate violence in the demand for freedom, in the manner of her political mentor, Walker, she militantly advocates that blacks improve their skills, sharpen their minds, and heighten their expectations. Issues of freedom, liberty, and civil rights are central to the text’s message, as is her insistence that her vehemence is holy. Her religious conversion catalyzed her political life and propelled her into the public arena.

Appearing with most of Stewart’s writings, and, in fact, integral to these texts, are religious prayers and meditations on key issues in her life—gender, gaining education, race, and political concerns. God became, in Stewart’s estimation, an intercessor for the race. A biblical sense of morality, time, and prophetic resolution drives her texts. This is made especially clear in her call to women to educate themselves and their children. Stewart was not suggesting that African American women pursue literacy as a middle-class nicety but that education was a political necessity. The race would benefit from schools, libraries, and innovation offered to its women. Stewart was to speak forthrightly about women’s influence over husbands and children and the attendant obligation to be moral and progressive in their politics well before Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s 1848 Seneca Falls meeting where interested social reformers met, initiating the Women’s Right’s movement.

Nevertheless, Stewart’s “holy zeal” carried her beyond the political arena with which her Boston friends were comfortable. She demanded of men and women a responsibility for the health, morality, and economic and political fortunes of the race that they could not meet. As her friends fell away, she recognized that her time in the public stream had come to an end. In her final address before friends and political acquaintances, she asked, “What if I am a woman?” (Richardson, 68), going to the heart of public disenchantment with her stridency. Stewart recognized that her zeal transgressed the norms for female, especially black female, behavior. Yet, she wrote, “brilliant wit will shine, come from whence it will; and genius and talent will not hide the brightness of its luster” (Richardson, 70). Her enthusiasm for the progress of African Americans was a call that could not be dampened by waning public opinion.

This same address, “Mrs. Stewart’s Farewell Address to Her Friends in the City of Boston” (21 September 1833), served as a eulogy to her fiery public career. Stewart continued her activism in New York and Washington, D.C. In New York she attended the 1837 Women’s Anti-Slavery Convention and was a member of a black women’s literary society. In the District of Columbia, in the early 1870s, she served as matron of the Freedmen’s Hospital and Asylum, a refuge for Civil War veterans, freed slaves, and their families. The Hospital and Asylum housed and trained the physically and mentally ill, the homeless, and those displaced by the significant cultural, economic, and social shifts brought on by the end of the war and Reconstruction.

In 1879 Stewart published Meditations by Mrs. Maria W. Stewart, which includes autobiographical information about her experiences during the Civil War. She died later that year while occupying the matron’s position at the hospital and was buried on 17 December 1879, exactly fifty years after her husband, James, in Graceland Cemetery, Washington, D.C. Eulogized in The People’s Advocate, a black newspaper circulated in Washington, D.C., she was remembered for her missionary work throughout Baltimore and Washington and for her generosity toward those in straitened circumstances.

Stewart was the first American woman to address a race- and sex-mixed audience publicly during an era when women’s public speech was usually restricted to female audiences and African Americans generally did not address whites on political or moral issues. Her deep commitment to moral and religious purity and to the abolition of slavery led her to strident public advocacy in a manner uncommon for women of her day.

Hinks, Peter, ed. David Walker’s Appeal, to the Coloured Citizens of the World, but in Particular, and Very Expressly, to Those of the United States of America (2000).

Logan, Shirley Wilson. With Pen and Voice: A Critical Anthology of Nineteenth-Century African American Women (1995).

Richardson, Marilyn, ed. Maria W. Stewart, America’s First Black Woman Political Writer (1987).

Obituary: The People’s Advocate, 28 Feb. 1880.

—MARTHA L. WHARTON

STILL, WILLIAM

STILL, WILLIAM(7 Oct. 1821–14 July 1902), abolitionist and businessman, was born near Medford in Burlington County, New Jersey, the youngest of the eighteen children of Levin Still, a farmer, and Charity (maiden name unknown). Still’s father, a Maryland slave, purchased his own freedom and changed his name from Steel to Still. His mother escaped from slavery and changed her given name from Cidney to Charity. With a minimum of formal schooling, William studied on his own, reading whatever was available to him. He left home at age twenty to work at odd jobs and as a farmhand. In 1844 he moved to Philadelphia, where he found employment as a handyman, and in 1847 he married Letitia George. They had four children.

In 1847 the Pennsylvania Society for the Abolition of Slavery hired Still as a clerk, and he soon began assisting fugitives from slavery who passed through the city. After the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, the society revived its Vigilance Committee to aid and support fugitive slaves and made Still chairman. One of the fugitives he helped was Peter Still, his own brother who had been left in slavery when his mother escaped. Finding Peter after a forty-year separation inspired Still to keep careful records of the former slaves, and those records later provided source material for his book on the Underground Railroad.

While with the Vigilance Committee, Still helped hundreds of fugitive slaves, and several times he nearly went to prison for his efforts. In 1855, when former slaves in Canada were being maligned in the press, he and his brother traveled there to investigate for themselves. His reports were much more positive and optimistic than the others and helped counteract rumors that former slaves were lazy and lawless. Five years later he cited cases of successful former slaves in Canada in a newspaper article that argued for freeing all the slaves.

Although Still had not approved of John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry, afterward Brown’s wife stayed with the Stills for a time, as did several of Brown’s accomplices. Still’s work in the antislavery office ended in 1861, but he remained active in the society, which turned to working for African American civil rights. He served as the society’s vice president for eight years and as president from 1896 to 1901.

Still’s book, The Underground Railroad (1872), was unique. The only work on that subject written by an African American, it was also the only day-by-day record of the workings of a vigilance committee. While he gave credit to “the grand little army of abolitionists,” he put the spotlight on the fugitives themselves, saying “the race had no more eloquent advocates than its own self-emancipated champions.” Besides recording their courageous deeds, Still hoped that the book would demonstrate the intellectual ability of his race. Along with the records of slave escapes he included excerpts from newspapers, legal documents, correspondence of abolitionists and former slaves, and some biographical sketches. He published the book himself and sent out agents to sell it. The book went into three editions and was exhibited at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition in 1876.

Although he had not suffered personally under slavery, Still faced discrimination throughout his life and was determined to work for improved race relations. His concern about civil rights in the North led him in 1859 to write a letter to the press, which started a campaign to end racial discrimination on Philadelphia streetcars, where African Americans were permitted only on the unsheltered platforms. Eight years later the campaign met success when the Pennsylvania legislature enacted a law making such discrimination illegal. In 1861 he helped organize and finance the Pennsylvania Civil, Social, and Statistical Association to collect data about the freed slaves and to press for universal suffrage.

Still was a skilled businessman as well as an effective antislavery agent. He began purchasing real estate while working for the antislavery society. After leaving that position he opened a store where he sold new and used stoves and coal. In 1861 he opened a coal yard, a highly successful business that led to his being named to the Philadelphia Board of Trade. In 1864 he was appointed post sutler at Camp William Penn, where black soldiers were stationed.

Still’s independent nature was illustrated in 1874 when he repudiated the Republican candidate for mayor of Philadelphia and supported instead a reform candidate. He explained his position at a public meeting and later in a pamphlet entitled An Address on Voting and Laboring (1874). He was also a lifelong temperance advocate, and as a member of the Presbyterian Church he established a Mission Sabbath School. His other civic activities included membership in the Freedmen’s Aid Commission, organizing around 1880 one of the first YMCAs for black youth, and helping to manage homes for the aged and for destitute black children and an orphan asylum for children of black soldiers and sailors. Poor health forced him to retire from his business affairs six years before his death at his home in Philadelphia.

Part of William Still’s journal of the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee, along with some personal correspondence, is in the Historical Society of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

Still, William. A Brief Narrative of the Struggle for the Rights of the Colored People of Philadelphia in the City Railway Cars (1867).

Gara, Larry. “William Still and the Underground Railroad,” Pennsylvania History 28 (Ian. 1961): 33–44.

Norwood, Alberta S. “Negro Welfare Work in Philadelphia Especially as Illustrated by the Career of William Still,…” M.A. thesis, Univ. of Penn., 1931.

Obituary: Philadelphia Public Ledger, 15 July 1902.

—LARRY GARA

STILL, WILLIAM GRANT

STILL, WILLIAM GRANT(11 May 1895–3 Dec. 1978), composer, orchestrator, arranger, and musician, once called the “Dean of Afro-American Composers,” was born in Woodville, Mississippi, the son of William Grant Still, a music teacher and bandmaster, and Carrie Lena Fambro, a schoolteacher. His father died during Still’s infancy. Still and his mother moved to Little Rock, Arkansas, where she taught school and in 1909 or 1910 married Charles Shepperson, a railway postal clerk, who strongly supported his stepson’s musical interests. Still graduated from high school at sixteen, valedictorian of his class, and went to Wilberforce University.

Still’s mother had wanted him to become a doctor, but music became his primary interest. He taught himself to play the oboe and clarinet, formed a string quartet in which he played violin, arranged music for his college band, and began composing; a concert of his music was presented at the school. In 1915, just a few months shy of graduation, Still dropped out of Wilberforce in order to become a professional musician, playing in various dance bands, including one led by W. C. HANDY, “the Father of the Blues.” That year he married Grace Bundy, with whom he had four children. They divorced in the late 1920s.

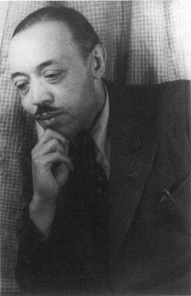

William Grant Still, trained at both Oberlin Conservatory and the New England Conservatory in Boston, composed jazz, popular music, opera, and classical works with African American themes. Library of Congress/Carl Van Vechten

A small legacy from his father, which Still inherited on his twenty-first birthday, allowed him to resume his musical studies in 1917, this time at Oberlin College’s conservatory. World War I interrupted Still’s studies, and he spent it in the segregated U.S. Navy as a mess attendant and as a violinist in an officers’ mess. After being discharged in 1919, Still returned to the world of popular music. He had a strong commitment to serious music and received further formal training during a short stay in 1922 at the New England Conservatory. From 1923 to 1925 he studied, as a private scholarship pupil, with the noted French “ultra-modernist” composer Edgard Varèse, whose influence can be heard in the dissonant passages found in Still’s early serious work.

Still managed to make his way both in the world of popular entertainment and as a serious composer. He worked successfully into the 1940s in the entertainment world as a musician, arranger, orchestrator, and conductor. As an arranger and orchestrator, he worked on a variety of Broadway shows, including the fifth edition of Earl Carroll’s Vanities. He also worked with a wide variety of entertainers, including Paul Whiteman, Sophie Tucker, and Artie Shaw. Still arranged Shaw’s “Frenesí,” which became one of the best-selling “singles” of all time. He also conducted on the radio for all three networks and was active in early television.

Despite his many commercial activities, Still also produced more serious efforts. Initially these works, such as From the Land of Dreams (written in 1924 and first performed a year later) and Darker America (also written in 1924 and first performed two years later), were described by critics as being “decidedly in the ultra-modern idiom.” He soon moved into a simpler harmonic milieu, often drawing on jazz themes, as in From the Black Belt (written in 1926 and first performed in 1927), a seven movement suite for orchestra.

Still’s most successful and best-known work, Afro-American Symphony (completed in 1930 and first performed a year later), draws heavily on the blues idiom; Still said he wanted “to demonstrate how the blues, so often considered a lowly expression, could be elevated to the highest musical level.” To some extent the symphony is “programmatic,” since after its completion Still added verses by black poet PAUL LAURENCE DUNBAR that precede each movement. Still believed that his symphony was probably the first to make use of the banjo. The work was well received and has continued to be played in the United States and overseas.

Still was a prodigious worker. His oeuvre includes symphonies, folk suites, tone poems, works for band, organ, piano, and violin, and operas, most of which focus on racial themes. His first opera, Blue Steel (completed in 1935), addresses the conflict between African voodooism and modern American values; its main protagonist is a black worker in Birmingham, Alabama. Still’s first staged opera, Troubled Island (completed in 1938), which premiered at the New York City Opera in March 1949, centers around the character of Jean Jacques Dessalines, the first emperor of Haiti. The libretto, begun by the black poet LANGSTON HUGHES and completed by Verna Arvey, depicts the Haitian leader’s stirring rise and tragic fall. Still married Arvey in 1939; the couple had two children. Arvey was to provide libretti for a number of Still’s operas and choral works.

Among Still’s other notable works are And They Lynched Him on a Tree (1940), a plea for brotherhood and tolerance presented by an orchestra, a white chorus, a black chorus, a narrator, and a soloist; Festive Overture (1944), a rousing piece based on “American themes”; Lenox Avenue, a ballet, with scenario by Arvey, commissioned by CBS and first performed on radio in 1937; Highway 1, USA (1962), a short opera, with libretto by Arvey, dealing with an incident in the life of an American family and set just off the highway in a gas station.

Still received many awards. Recognition had come relatively early to him—in 1928 the Harmon Foundation honored him with its second annual award, given to the person judged that year to have made the “most significant contribution to Negro culture in America.” He won successive Guggenheim Fellowships in 1934 and 1935 and was awarded a Rosenwald Fellowship in 1939.

Still’s early compositions were in an avant-garde idiom, but he soon turned to more conventional melodic and harmonic methods, in what he later described as “an attempt to elevate the folk idiom into symphonic form.” This transition may have made his serious work more accessible, but for much of his career he sustained himself and his family by pursuing more commercially successful endeavors.

Still dismissed the black militants who criticized his serious music as “Eur-American music,” insisting that his goal had been “to elevate Negro musical idioms to a position of dignity and effectiveness in the fields of symphonic and operatic music.” And at a 1969 Indiana University seminar on black music he asserted, “I made this decision of my own free will . . . . I have stuck to this decision, and I’ve not been sorry.”