VANDERZEE, JAMES AUGUSTUS JOSEPH

VANDERZEE, JAMES AUGUSTUS JOSEPH VANDERZEE, JAMES AUGUSTUS JOSEPH

VANDERZEE, JAMES AUGUSTUS JOSEPH(29 June 1886–15 May 1983), photographer and entrepreneur, was born in Lenox, Massachusetts, the second of six children of John VanDerZee and Susan Elizabeth Egberts. Part of a working-class African American community that provided services to wealthy summer residents, the VanDerZees (sometimes written Van Der Zee or Van DerZee) and their large extended family operated a laundry and bakery and worked at local luxury hotels. James played the violin and piano and enjoyed a bucolic childhood riding bicycles, swimming, skiing, and ice fishing with his siblings and cousins. He received his first camera from a mail-order catalogue just before his fourteenth birthday and taught himself how to take and develop photographs using his family as subjects. He left school that same year and began work as a hotel waiter. In 1905 he and his brother Walter moved to New York City.

James was working as an elevator operator when he met a seamstress, Kate Brown. They married when Kate became pregnant, and a daughter, Rachel, was born in 1907. A year later a son, Emile, was born but died within a year. (Rachel died of peritonitis in 1927.) In addition to a series of service jobs, VanDerZee worked sporadically as a musician. In 1911 he landed his first photography-related job at a portrait studio located in the largest department store in Newark, New Jersey. Although he was hired as a darkroom assistant, he quickly advanced to photographer when patrons began asking for “the colored fellow.” The following year VanDerZee’s sister Jennie invited him to set up a small studio in the Toussaint Conservatory of Art, a school she had established in her Harlem brownstone. Convinced that he could make a living as a photographer, VanDerZee wanted to open his own studio, but Kate was opposed to the venture. This fundamental disagreement contributed to the couple’s divorce in 1917.

Self-portrait of the photographer James VanDerZee. © Donna Mussenden VanDerZee

VanDerZee found a better companion and collaborator in Gaynella Greenlee, a woman of German and Spanish descent who, after marrying VanDerZee in 1917, claimed to be a light-skinned African American. That same year the couple opened the Guarantee Photo Studio, later the GGG Photo Studio, on West 135th Street, next door to the Harlem branch of the New York Public Library. This was the first of four studio sites VanDerZee would rent over the next twenty-five years. With his inventive window displays and strong word of mouth within the burgeoning African American community, VanDerZee quickly established himself as Harlem’s preeminent photographer.

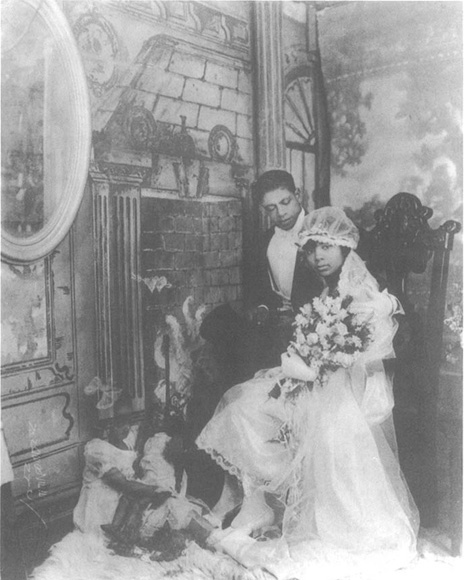

By the early 1920s VanDerZee had developed a distinct style of portrait photography that emphasized narrative, mood, and the uniqueness of each image. Harlem’s African American citizens—couples, families, co-workers, and even family pets—had their portraits taken by VanDerZee. With a nod to Victorian photographers, he employed a range of props, including fashionable clothes and exotic costumes, and elaborate backdrops (many of which he painted himself) featuring landscapes or architectural elements. Although they appear natural and effortless, VanDerZee’s portraits were deliberately constructed compositions, with sitters posed in complex and artful arrangements. “I posed everyone according to their type and personality, and therefore almost every picture was different” (McGhee). VanDerZee made every sitter look and feel like a celebrity, even mimicking popular media images on occasion. In VanDerZee’s photographs, sitters appear sophisticated, urbane, and self-aware, and Harlem emerges as a prosperous, healthy, and diverse community.

Future Expectations, c. 1926. © Donna Mussenden VanDerZee

Another characteristic of VanDerZee’s portrait work was his creative manipulation of prints and negatives, which included retouching, double printing, and hand painting images. In addition to improving sitters’ imperfections, retouching and hand painting added dramatic and narrative details, like tinted roses or a wisp of smoke rising from an abandoned cigarette. VanDerZee often employed double printing—at times using as many as three or four negatives to make a print—to introduce theatrical storytelling elements into his portraits.

Such attention to detail was commercial as well as artistic. VanDerZee never forgot that photography was essentially a commercial venture and that making his patrons happy and his images one of a kind helped business. He regularly took on trade work, creating calendars and advertisements and, in later years, photographing autopsies for insurance companies and identification cards for taxi drivers. But portraits, of both the living and the dead, were VanDerZee’s bread and butter. Funerary photography, a practice begun in the nineteenth century and popular in some communities through the mid-twentieth century, was a major part of his business. VanDerZee’s daily visits to funeral parlors culminated in his book Harlem Book of the Dead (1978). Harlemites of every background hired VanDerZee to document their weddings, baptisms, graduations, and businesses with portraits and on-site photographs. Organizations as diverse as the Monte Carlo Sporting Club, Les Modernes Bridge Club, the New York Black Yankees, the Renaissance Big Five basketball team, MADAME C. J. WALKER’s Beauty Salon, the Dark Tower Literary Salon, and the Black Cross Nurses commissioned VanDerZee portraits. Today these photographs serve as an invaluable and unique visual record of African American life during Harlem’s heyday.

In the 1920s and 1930s and into the 1940s VanDerZee photographed the African American leaders living and working in Harlem, including the entertainment and literary luminaries of the Harlem Renaissance BILL “BOJANGLES” ROBINSON, JELLY ROLL MORTON, and COUNTEÉ CULLEN; the boxing legends JACK JOHNSON and JOE LOUIS; and the political, business, and religious leaders Adam Clayton Powell Sr. and ADAM CLAYTON POWELL JR., A’lelia Walker, FATHER DIVINE, and DADDY GRACE. In a move that anticipated the birth of photojournalism, VanDerZee took to documenting street life and events when he was hired by MARCUS GARVEY to create photographic public relations material for the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) in 1924. VanDerZee produced several thousand prints of UNIA parades, rallies, and the fourth international convention, including many of the most reproduced images of Garvey.

Unlike many of its competitors, VanDerZee’s studio remained profitable throughout the Depression. After World War II, however, business steadily declined, the result of the popularity of portable cameras, changing aesthetic styles, and the broader financial decline of Harlem as middle-class blacks moved away from the area. In 1945 the Van-DerZees purchased the house they had been renting on Lenox Avenue, but by 1948 they had taken out a second mortgage and by the mid-1960s were facing foreclosure. Fighting for his economic survival, VanDerZee worked primarily as a photographic restorer.

The reevaluation of VanDerZee’s place in photographic history began with Harlem on My Mind, a groundbreaking and controversial 1969 exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. After being “discovered” by the photo researcher Reginald McGhee, VanDerZee became the single largest contributor to the exhibition, which drew seventy-seven thousand visitors in its first week. Unfortunately, the exhibition’s success arrived too late to help the cash-strapped couple, and the Van-DerZees were evicted from their Lenox Avenue house the day after the exhibition closed. Gaynella suffered a nervous breakdown as a result and remained an invalid until her death in 1976.

Hoping to resurrect his finances, VanDerZee established the James VanDerZee Institute in June 1969. With McGhee as project director, the institute published several monographs and organized nationwide exhibitions showcasing VanDerZee’s photographs alongside work by young African American photographers. In the early 1970s VanDerZee became a minor celebrity, appearing on television, in film, and as the subject of numerous articles. Meanwhile, he found himself living in a tiny Harlem apartment and relying on his Social Security payments, having received little financial support from the VanDerZee Institute. Several benefactors helped VanDerZee in fund-raising and in his attempts to wrest control of his photographic collection from the VanDerZee Institute, which in 1977 moved to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In 1978 the majority of his photographic materials held by the Metropolitan was transferred to the Studio Museum in Harlem, and in 1981 VanDerZee, who had saved almost every negative he had ever made, sued the museum for ownership of fifty thousand prints and negatives. The dispute was finally settled a year after VanDerZee’s death, when a New York court divided the collection between the VanDerZee estate, the VanDerZee Institute, and the Studio Museum.

In 1978 VanDerZee married Donna Mussenden, a gallery director thirty years his junior who physically and spiritually rejuvenated the ninety-two-year-old photographer. Encouraged by Mussenden, VanDerZee returned to portrait photography, and in the early 1980s photographed such prominent African Americans as BILL COSBY, MILES DAVIS, EUBIE BLAKE, MUHAMMAD ALI, OSSIE DAVIS, RUBY DEE, JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT, and ROMARE BEARDEN.

James VanDerZee died in 1983, just shy of his ninety-seventh birthday, on the same day he received an honorary doctorate from Howard University. Although he was omitted from Beaumont Newhall’s 1982 seminal volume The History of Photography, VanDerZee was honored in 2002 by the U.S. Postal Service with a postage stamp.

VanDerZee’s photographs chronicle African American life between the wars. His images of such landmarks as the Hotel Theresa and the Manhattan Temple Bible Club Lunchroom and of the ordinary drugstores, beauty salons, pool halls, synagogues, and churches of Harlem record the unprecedented migration of black Americans from the South to the North and from rural to urban living. His portraits offer a human-scale account of the New Negro and the Harlem Renaissance and of race pride and self-determination. Documenting the vitality and diversity of African American life, VanDerZee’s photographs countered existing popular images of African Americans, which historically rendered black Americans invisible or degenerate. Here, instead, are images testifying to the artistic, commercial, and political richness of the African American community.

Haskins, James. Van DerZee: The Picture Takin’ Man (1991).

McGhee, Reginald. The World of James Van DerZee: A Visual Record of Black Americans (1969).

Willis, Deborah. VanDerZee: Photographer 1886–1983 (1993).

Obituary: New York Times, 16 May 1983.

—LISA E. RIVO

VARICK, JAMES

VARICK, JAMES(1750–22 July 1827), Methodist leader, clergyman, and race advocate, was born near Newburgh in Orange County, New York, the son of Richard Varick. The name of his mother, who was a slave, is unknown. The family later relocated to New York City. With few educational opportunities for African American children growing up in New York City at the time, Varick by some means acquired very solid learning. Around 1790 Varick married Aurelia Jones; they had three girls and four boys. While he worked as a shoemaker and tobacco cutter and conducted school in his home and Church, the ministry was clearly his first love. Having embraced Christianity in the historic John Street Methodist Church, Varick served as an exhorter and later received a preacher’s license. Racial proscription in the Methodist Episcopal Church during the latter part of the 1700s and early 1800s prevented Varick, ordained a deacon in 1806, from receiving full elder’s orders until 1822.

Varick emerged as a major religious leader in New York. The Methodist Episcopal Church, like other mainly white denominations in postrevolutionary America, gradually but clearly abandoned a previous stance toward African American members that was more firmly antislavery and less discriminatory than was to be the case in later years. As a result, a number of black Methodists withdrew from white-controlled congregations to form separate racial churches, some of which eventually united to form independent black denominations by the 1820s. As early as 1796 Varick led a number of African Americans out of the John Street Church and formed a separate black congregation, which in 1800 entered its first building and in 1801 incorporated as the African Methodist Episcopal Church in New York. It was commonly known as Zion Church. Because of legal maneuvering involving the incorporation agreement and the persistent efforts of white ministers to have access to the Zion pulpit, the congregation continued to struggle to attain true autonomy within the Methodist Episcopal Church. Efforts to effect some type of self-governing status under the general rubric of the predominantly white denomination ultimately failed. The Methodist Episcopal Church officials in the New York area were unwilling to depart from normal denominational polity and governance, insisting that the leadership of the church should be selected by the general body.

Varick also helped to organize the John Wesley Church in New Haven, Connecticut, which later connected with Zion and other bodies to form an independent black denomination. The African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church (AMEZ) emerged between 1820 and 1824 under the leadership of Varick and others. Unwilling to remain under the governance of the Methodist Episcopal Church, Varick and his colleagues equally objected to joining the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME), formed in 1816 and headed by Bishop RICHARD ALLEN of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Apparently, they found Allen’s methods too autocratic and were alienated by the AME’s attempt to “invade” Zion’s domain by establishing congregations and seeking to win over churches to the AME in the New York City area. Varick was elected and consecrated the connection’s first superintendent in 1822; he was reelected in 1824 and held the post until his death in 1827. The connection did not affix “Zion” as a part of its official church tide until 1848, a move to distinguish it from its major competitor, the older AME. Denominating their chief officer as “superintendent” (although later they employed the terms “bishop” and “superintendent” interchangeably) and having him stand for election every four years, Varick and these Zionites clearly sought to differentiate themselves from the governance of both the Methodist Episcopal and the African Methodist Episcopal churches, including the goal of making provision for greater rights for the laity. Zionites in later decades, under attack from other Methodist bodies for not having an “authentic” episcopacy, began to use the term “bishop” more frequently and, perhaps for this and other reasons, eventually began electing these officers for life terms in 1880.

Varick tirelessly labored on behalf of racial freedom and advancement. In 1808 he delivered the thanksgiving sermon in a celebration in the Zion Church marking the federal government’s prohibition of the importation of slaves. He also played a prominent role in William Hamilton’s New York African Society for Mutual Relief, organized in 1808. Quite possibly Varick played a role in establishing the first African American masonic lodge in New York State, the Lodge of Freemasonry, or African Lodge, begun in 1812. The Methodist leader also served as one of the first vice presidents of the New York African Bible Society, founded in 1817 and later affiliated with the American Bible Society. Varick joined a group of religious and business leaders in supporting a petition to secure voting rights for blacks at the state constitutional convention held in 1821. The group’s effort met with some success. After much discussion the convention approved a limited extension of suffrage conditioned by property ownership, the payment of taxes, and age.

He fought strenuously against the effort of the American Colonization Society (formed in 1816–1817) to repatriate blacks in Africa, joining with others to establish the African Wilberforce Benevolent Society of New York and other organizations to secure racial justice. Varick, along with black leaders such as PETER WILLIAMS JR. and Richard Allen, was instrumental in helping JOHN BROWN RUSSWURM and SAMUEL CORNISH publish in March 1827 the first black newspaper, Freedom’s Journal, which operated for one year out of the Zion Church. Bishop Varick died in New York several months after the emergence of this newspaper and eighteen days after Independence Day 1827, the deadline set by the state of New York for all of its enslaved residents to attain their freedom. While he has been neglected in scholarly circles, Varick stands in history as one of the major leaders of American religion and independent black Christianity, as well as a testimony to the key role that African American church leaders played in effecting political and economic freedom for the entire race.

Walls. William J. The African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church: Reality of the Black Church (1974).

—SANDY DWAYNE MARTIN

VAUGHAN, SARAH

VAUGHAN, SARAH(27 Mar. 1924–3 Apr. 1990), jazz singer, was born Sarah Lois Vaughan in Newark, New Jersey, to Asbury Vaughan, a carpenter, and Ada Vaughan, a laundress. Her father, who played guitar for pleasure, and her mother, who sang in the choir of the local Mount Zion Baptist Church, gave their only daughter piano lessons from the age of seven. Before her teens Vaughan was playing organ in church and singing in the choir. In 1942, on a dare from a friend, she took the subway into Harlem and entered the Apollo Theatre’s legendary Wednesday-night amateur contest. She won the ten-dollar first prize and a week-long spot there as an opening act.

That engagement launched a singer who would soon develop a voice of operatic splendor and an imagination to match. Embraced early on by the pioneers of bebop, “The Divine One,” as she was called, absorbed their innovations and applied them lavishly to the Great American Songbook. Gunther Schuller, the Pulitzer Prize-winning classical conductor and scholar, called Vaughan the greatest vocal artist of the twentieth century: “Hers is a perfect instrument, attached to a musician of superb instincts” (Liska, 19). Unlike her peer Carmen McRae, Vaughan was no probing interpreter of words. She communicated drama through sound, wallowing in a seemingly endless range of textures. In one drawn-out note she could change timbres repeatedly, from dulcet to husky, or make a feathery leap from bass to soprano.

After hearing her sing at the Apollo, crooner Billy Eckstine, a reigning black heartthrob of the day, took her to meet his boss, the pianist and bandleader Earl “Fatha” Hines. Soon Vaughan was sharing the bandstand with Eckstine, as well as bebop pioneers CHARLIE PARKER and DIZZY GILLESPIE, who were in Hines’s band. “I thought Bird and Diz were the end,” said Vaughan. “Horns always influenced me more than voices” (Gold, 13). But she borrowed a lot from Eckstine, whose voluptuous swoops and overripe vibrato turned up in Vaughan’s singing.

Sarah Vaughan, jazz singer and musician who was awarded the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1989. Library of Congress

In the summer of 1944 Eckstine left Hines to form a groundbreaking bebop orchestra and took Vaughan with him. She made her first recording, “I’ll Wait and Pray,” with the band on 5 December 1944. Thereafter she recorded for several small bop labels. But it was clear to George Treadwell, a handsome trumpeter with whom she shared a bill in 1946, that Vaughan’s voice had commercial potential. After a brief courtship, they wed on 17 September of that year. Treadwell became her manager, investing thousands of dollars on a makeover for his wife, including a nose job, teeth straightening, and gowns.

Also in 1946, a glamorized Vaughan joined a new label, Musicraft. In 1947 her luscious cover version of Doris Day’s hit “It’s Magic” climbed to number eleven. The next year she covered NAT KING COLE’s “Nature Boy,” reaching number nine. Every year from 1947 through 1952 she won Down Beat’s poll as best female jazz singer; through 1959 she had twenty-six Top Forty singles.

Vaughan’s straddling of jukebox pop and modern jazz tended to frustrate both worlds. She went on the defense. “I’m not a jazz singer, I’m a singer,” she said, while naming a wide range of favorite colleagues, from MAHALIA JACKSON to Polly Bergen (Liska, 21). In a fruitful relationship with Columbia from 1949 to 1953, Vaughan recorded show tunes, saccharin torch songs like “My Tormented Heart,” and a now-classic LP with MILES DAVIS.

In 1954 she signed a dual contract with a pop label, Mercury, and its jazz subsidiary, EmArcy. Among the jazz milestones she created is Sarah Vaughan, a 1954 small-group album that teamed her with a bebop wunderkind, trumpeter Clifford Brown. Vaughan gained a new trademark in 1958 when she recorded “Misty,” the Erroll Garner-Johnny Burke ballad, with a twinkly, sugar-dusted arrangement credited to QUINCY JONES. Her commercial stature rose as she recorded a series of kitschy hits, notably “Broken-Hearted Melody” (1959), a country-pop ditty with a heavy backbeat and a male chorus singing “doomp-do-doomp” behind her. “God, I hated it,” she said later. “It’s the corniest thing I ever did” (Liska, 21). Yet it reached number seven and lifted her into a glamorous rank of white supper clubs. Vaughan even appeared in a 1960 gangster film, Murder Inc.

Also in 1960 Vaughan accepted a lucrative offer from Roulette, a gangster-run rock and jazz label. Through 1963 she created some of her best-loved work at Roulette: late-night jazz with guitar and bass (After Hours and Sarah + 2) and sessions with the Benny Carter and COUNT BASIE orchestras. But she also made a series of string-laden ballad discs, and jazz purists continued to attack her. The grumbling rose during her second stint at Mercury, from 1963 to 1967. Vaughan later claimed that she quit the label, citing various grievances: she hated the pop material, the records were not promoted, and she was not getting royalties. She did not record again until 1971.

Vaughan’s luck with men was not much better. Having divorced Treadwell in 1956—she claimed that all he had done for her had been for himself—Vaughan had taken on a new husband-manager in 1959: Clyde “C. B.” Atkins, a former professional football player who now owned a Chicago taxi fleet. In 1961 the couple adopted a child, Deborah (now Paris Vaughan, an actress). Divorcing the violent Atkins in the 1960s, Vaughan found he had left her in heavy debt to the Internal Revenue Service. From 1970 through 1977 she had a more pleasant relationship with Marshall Fisher, a restaurateur who became her manager. But when asked in an interview about the men in her life, an angry Vaughan threatened to “throw up” (O’Connor, 96).

Vaughan’s career gained new life when she signed with Mainstream, a jazz label run by Bob Shad, her producer at EmArcy. She made more blatant pop albums, along with Live in Japan, a double LP of Vaughan singing the standards she loved with a first-rate trio, and Sarah Vaughan with Michel Legrand, a sumptuous orchestral collaboration with the celebrated French composer-arranger. For the rest of her life Vaughan was a touring machine, second only to ELLA FITZGERALD as a living legend of vocal jazz. No longer did she record fluff. From 1977 through 1982 she made a series of uncompromising jazz albums for the Pablo label. These included Send in the Clowns (1982), Vaughan’s third LP with the Count Basie Orchestra. The title song, from Stephen Sondheim’s A Little Night Music, was her key showstopper of later years. Singing the lament of an actress who has triumphed onstage but not in love, the shy and private Vaughan gave a rare flash of autobiography. She delivered the song as a slow, emotional aria, lingering on the words, “Sure of my lines / No one is there.” Returning to Columbia, she recorded the Grammy Award-winning Gershwin Live (1982), a symphonic program she performed for years.

By now Vaughan had ended another marriage, to trumpeter Waymon Reed. Though sixteen years her junior, he died of cancer in 1983. Vaughan herself had smoked, drunk, and snorted cocaine for decades, with little audible damage. Her 1987 album, Brazilian Romance, proved this. But in 1989, soon after she won a Grammy for lifetime achievement, Vaughan was diagnosed with lung cancer. That October she returned to the Blue Note jazz club, her New York headquarters of the 1980s, for what would be her final performances. On 3 April 1990, one week after turning sixty-six, she died at her home in Hidden Hills, a Los Angeles suburb.

All of Vaughan’s Mercury recordings are available in four box sets; her Roulette sides are gathered in The Complete Roulette Sarah Vaughan Studio Sessions (Mosaic). In 1991 the Public Broadcasting System aired a television documentary on Vaughan, The Divine One, as part of its American Masters series. In 2002 singer Dianne Reeves won a Grammy for her tribute album to Vaughan, The Calling. Reeves explained: “I’d never heard a voice like that, that was so rich and deep and beautiful, just sang all over the place. I thought, ‘You mean, there are those kinds of possibilities?’” (Interview with author, 2000).

Dahl, Linda. Stormy Weather: The Music and Lives of a Century of Jazzwomen (Limelight Editions, 1996).

Gardner, Barbara. Down Beat, 2 Mar. 1961.

Gavin, James. Liner note essay for The Complete Roulette Sarah Vaughan Studio Sessions (Mosaic Records 8-CD set)

Gold, Don. Down Beat, 30 May 1957.

Liska, A. James. Down Beat, May 1982.

Mackin, Tom. “Newark’s Divine Sarah.” Newark Sunday News, 10 Nov. 1968.

O’Connor, Rory. New York Woman, Apr. 1988.

“Queen for a Year.” Metronome, Feb. 1951.

Obituary: New York Times, 5 Apr. 1990.

—JAMES GAVIN

VESEY, DENMARK

VESEY, DENMARK(c. 1767–2 July 1822), mariner, carpenter, abolitionist, was born either in Africa or the Caribbean and probably grew up as a slave on the Danish colony of St. Thomas, which is now a part of the U.S. Virgin Islands. When Denmark was about fourteen years old, the slave trader Captain Joseph Vesey purchased him to sell on the slave market in Saint Domingue (Haiti). The identity of Denmark Vesey’s parents and his name at birth are unknown, but Joseph Vesey gave him the name “Telemaque.” He became “Denmark Vesey” in 1800, after he purchased his freedom from lottery winnings. Vesey’s family life is difficult to reconstruct. He had at least three wives and several children, including three boys—Sandy, Polydore, and Robert—and a girl, Charlotte. His first and second wives, Beck and Polly, and their children lived as slaves. His third wife, Susan, was a free woman of color.

Not suitable for sale in Haiti, Telemaque became Captain Vesey’s slave and “cabin boy” and moved with him to Charleston, South Carolina, in 1783. In Charleston Vesey labored as an urban slave for nearly seventeen years. As a chandler’s man and a multilingual laborer who could read and write in English and French, Denmark Vesey conducted business for his owner’s trade company. He was part of a large, diverse, and stratified urban black community that outnumbered the local white population. The occupations of black Charlestonians, a mixture of slave and free persons, varied; the population included artisans, domestics, agriculturalists, and other skilled and unskilled laborers. African Americans took advantage of the city’s illicit trade network as they struggled to make a living in a challenging environment, where they faced white oppression and intraracial economic competition.

In 1799, at age thirty-three, Vesey purchased his freedom, joining just over 3,100 other people of color who made up Charleston’s community of free blacks. State regulations made life for free persons of color semiautonomous at best. Free blacks had white patrons and paid annual “freedom” taxes, which left them vulnerable to white control as they labored in a city determined to limit their earning potential, social standing, and political power. South Carolina slaveholders hired out laborers for the Charleston market, thus creating economic tensions among free and enslaved black laborers. Divisions mounted as distinctions were drawn between blacks and those who were of mixed race. In this complex society Vesey apprenticed under established craftsmen and became a well-known and respected carpenter. Marginalized from the free community of light-skinned blacks, Vesey readily identified with rural and urban slaves who lived an arduous life that he remembered all too well.

At the turn of the century Vesey joined a growing number of southern blacks and converted to Christianity. After a short-term membership in a segregated congregation of the Second Presbyterian Church, he became a Methodist. Inspired by RICHARD ALLEN’s movement in Philadelphia, Charleston’s black Methodist population, which outnumbered whites of the same faith, established their own church. By 1818 the African Methodist Church had become the centerpiece for black religious congregation and supported political and economic activism. Influenced by Old Testament teachings, Vesey grew increasingly critical of slavery and commonly spoke against the institution. He compared the African American plight to that of the Israelites and joined America’s rising antislavery fervor by arguing that white slaveholders denied blacks rights that were sanctioned by God. These debates inspired a grand scheme of resistance to South Carolina’s aged slavery institution.

It is not known how long Vesey planned his resistance movement. Some modern scholars and primary-source accounts maintain that his plot was detailed, well organized, and that Vesey discussed the plan at length with a small group of trusted lieutenants. His accused co-conspirators, Peter Poyas, Rolla Bennett, Monday Gell, and Jack Pritchard, were all members of the African Methodist Church. The movement sought the assassination of South Carolina’s governor and Charleston’s mayor, and the rebels planned to take the militia arsenal, burn the city, and slaughter white citizens. They believed that blacks from the countryside and city would join the uprising as it grew, culminating in a mass exodus to Haiti, where President Jean-Pierre Boyer had encouraged free-black American immigration. A series of confessions exposed the conspiracy and led to the arrest of 128 black men. Thirty-five of those arrested were hanged, and forty were transported for their roles as co-conspirators in the revolt. Based on confessions and testimonies, South Carolina’s courts named Vesey the chief organizer of the revolt and sentenced him to execution. He was hanged on 2 July 1822.

Vesey became a martyr for the American antislavery movement and a symbol for black resistance following his alleged role as mastermind of the 1822 insurrection. His life, the revolt, and his death have raised questions about nineteenth-century race relations and black resistance. Historians still debate whether the 1822 events in Charleston represented a failed, however expertly designed, uprising or whether the alleged Vesey rebellion occurred only in the minds of whites, and was fueled by rumors and deep-rooted white fears of slave resistance. The question remains, Was Denmark Vesey falsely accused because he was a literate and outspoken free black who used his thorough knowledge of Christianity to challenge American slavery? Or did he take this spirit of protest a step further, to plan what would have been, prior to NAT TURNER’s rebillion in 1830, the largest slave revolt in U.S. history?

Egerton, Douglas R. He Shall Go Out Free: The Lives of Denmark Vesey (1999).

Lofton, John. Denmark Vesey’s Revolt: The Slave Plot That Lit a Fuse to Fort Sumter (1983).

Pearson, Edward A. Designs against Charleston: The Trial Record of the Denmark Vesey Slave Conspiracy of 1822 (1999).

Robertson, David. Denmark Vesey: The Buried Story of America’s Largest Slave Rebellion and the Man Who Led It (1999).

—TIWANNA M. SIMPSON