WIGGINS, THOMAS BETHUNE.

WIGGINS, THOMAS BETHUNE.Upon graduation from college, White became an executive with the Standard Life Insurance Company, one of the largest black-owned businesses of its day. Part of Atlanta’s “New Negro” business elite, White was a founder of a real estate and investment company and looked forward to a successful business career. He also participated in civic affairs: in 1916 he was a founding member and secretary of the Atlanta branch of the NAACP. The branch experienced rapid growth, largely because, in 1917, it stopped the school board from eliminating seventh grade in the black public schools. White was an energetic organizer and enthusiastic speaker, qualities that attracted the attention of NAACP field secretary JAMES WELDON JOHNSON. The association’s board of directors, at Johnson’s behest, invited White to join the national staff as assistant secretary. White accepted, and in January 1918 he moved to New York City.

During White’s first eight years with the NAACP, his primary responsibility was to conduct undercover investigations of lynchings and racial violence, primarily in the South. Putting his complexion in service of the cause, he adopted a series of white male incognitos—among the cleverer ones were itinerant patent-medicine salesman, land speculator, and newspaper reporter intent on exposing the libelous tales being spread in the North about white southerners—and fooled mob members and lynching spectators into providing detailed accounts of the recent violence. Upon White returning to New York from his investigative trips, the NAACP would publicize his findings, and White eventually wrote several articles on the racial carnage of the post-World War I era that appeared in the Nation, the New Republic, the New York Herald-Tribune, and other prestigious journals of liberal opinion. By 1924 White had investigated forty-one lynchings and eight race riots. Among the most notorious of these was the 1918 lynching in Valdosta, Georgia, of Mary Turner, who was set ablaze. Turner was nine months pregnant, her womb was slashed open, and her fetus was crushed to death. White also investigated the bloody race riots that left hundreds of African Americans dead in Chicago and in Elaine, Arkansas, during the “red summer” of 1919, and the 1921 riot in Tulsa, Oklahoma, that resulted in the leveling of the black business district and entire residential neighborhoods. White’s investigations also revealed that prominent and respected whites participated in racial violence; the mob that perpetrated a triple lynching in Aiken, South Carolina, in 1926, for example, included local officials and relatives of the governor.

White wrote of his undercover investigations in the July 1928 American Mercury and in Rope and Faggot (1929), a detailed study of the history of lynching and its place in American culture and politics that remains indispensable. His derring-do in narrowly escaping detection and avoiding vigilante punishment was also rendered in verse in LANGSTON HUGHES’S “Ballad of Walter White” (1941).

At the same time that he was exposing lynching, White also emerged as a leading light in the Harlem Renaissance. He authored two novels. The Fire in the Flint (1924) was the second novel to be published by a New Negro, appearing just after JESSIE FAUSET’S There Is Confusion. Set in Georgia after World War I and based on White’s acquaintance with his native state, The Fire in the Flint tells the story of the racial awakening of Kenneth Harper, who pays for his new consciousness when a white mob murders him. The novel was greeted with critical acclaim and was translated into French, German, Japanese, and Russian. His second work of fiction, Flight (1926), set in New Orleans, Atlanta, and New York, is both a work about the Great Migration of blacks to the North and story about “passing.” Flight’s reviews were mixed. White’s response to one of the negative reviews—by the African American poet Frank Home, in Opportunity magazine—is instructive. He complained to the editor about being blindsided and parlayed his dissatisfaction into a debate over his book’s merits that stretched over three issues. To White there was no such thing as bad publicity—in art or in politics. The salient point was to keep a topic—a book or a political cause—firmly in public view, which would eventually create interest and sympathy.

White’s dynamism and energy was central to the New Negro movement. He was a prominent figure in Harlem’s nightlife, chaperoning well-connected and sympathetic whites to clubs and dances. He helped to place the works of Langston Hughes, COUNTÉE CULLEN, and CLAUDE MCKAY with major publishers, and promoted the careers of the singer and actor PAUL ROBESON, the tenor Roland Hayes, and the contralto MARIAN ANDERSON.

When James Weldon Johnson retired from the NAACP in 1929, White, who had been looking to assume more responsibility, succeeded him. As the association’s chief executive, White had a striking influence on the civil rights movement’s agenda and methods. In 1930 he originated and orchestrated the victorious lobbying campaign to defeat President Hoover’s nomination to the Supreme Court of John J. Parker, a North Carolina politician and jurist who had publicly stated his opposition to black suffrage and his hostility to organized labor. During the next two election cycles, the NAACP worked with substantial success to defeat senators with significant black constituencies who had voted to confirm Parker. The NAACP became a recognized force in national politics.

During Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal and Harry Truman’s Fair Deal, White raised both the NAACP’s public profile and its influence on national politics. White’s success owed much to his special knack for organizing the more enlightened of America’s white elites to back the NAACP’s programs. Over the decade of the 1930s, he won the support of the majority of the Senate and House of Representatives for a federal antilynching law; only southern senators’ filibusters prevented its passage. His friendship with Eleanor Roosevelt likewise gave him unparalleled access to the White House. This proved invaluable when he conceived and organized Marian Anderson’s Easter Sunday 1939 concert at the Lincoln Memorial, which was blessed by the president and had as honorary sponsors cabinet members, other New Deal officials, and Supreme Court justices. As NAACP secretary and head of the National Committee against Mob Violence, White convinced President Truman in 1946 to form a presidential civil rights commission, which the following year issued its groundbreaking antisegregationist report, To Secure These Rights. In 1947 he persuaded Truman to address the closing rally of the NAACP’s annual meeting, held at the Washington Monument; it was the first time that a president had spoken at an association event.

As secretary, White oversaw the NAACP’s legal work, which after 1934 included lawsuits seeking equal educational opportunities for African Americans. He was also instrumental in convincing the liberal philanthropists of the American Fund for Public Service to commit one hundred thousand dollars to fund the endeavor, though only a portion was delivered before the fund became insolvent. After 1939 the day-to-day running of the legal campaign against desegregation rested with CHARLES HAMILTON HOUSTON and THURGOOD MARSHALL’S NAACP Legal Defense Fund, but White remained intimately involved in the details of the campaign, which culminated with the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling that declared the doctrine of “separate but equal” unconstitutional.

White had married Gladys Powell, a clerical worker in the NAACP national office, in 1922. They had two children, Jane and Walter Carl Darrow, and divorced in 1948. In 1949 he married Poppy Cannon, a white woman. This interracial union provoked a major controversy within both the NAACP and black America at large, and there was widespread sentiment that White should resign. In response, White, who was always an integrationist, claimed the right to marry whomever he wanted. He weathered the storm with the help of NAACP board member Eleanor Roosevelt, who threatened to resign should White be forced from office. Though White maintained the title of secretary, his powers were reduced, with ROY WILKINS taking over administrative duties. White continued to be the association’s public spokesperson until his death on 21 March 1955. In declining health for several years, he suffered a fatal heart attack in his New York apartment.

Unlike other NAACP leaders such as W. E. B. DU BOIS and Charles Houston, Walter White was neither a great theoretician nor a master of legal theory. His lasting accomplishment lay in his ability to organize support for the NAACP agenda among persons of influence in and out of government and to persuade Americans of all races to support the cause of equal rights for African Americans.

The bulk of Walter White’s papers are in the Papers of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, deposited at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., and the Walter Francis White/Poppy Cannon Papers, deposited at the Beinecke Rare Books and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut.

White, Walter. A Man Called White (1948).

Cannon, Poppy. A Gentle Knight: My Husband Walter White (1956).

Janken, Kenneth Robert. WHITE: The Biography of Walter White, Mr. NAACP (2003).

Obituaries: New York Times, 22 Mar. 1955; Washington Afro-American, 26 Mar. 1955.

—KENNETH R. JANKEN

WIGGINS, THOMAS BETHUNE.

WIGGINS, THOMAS BETHUNE.See Blind Tom.

WILDER, DOUGLAS

WILDER, DOUGLAS(17 Jan. 1931–), Governor of Virginia, was born Lawrence Douglas Wilder in Richmond, Virginia, the son of Robert J. Wilder Sr., a door-to-door insurance salesman, church deacon, and strict disciplinarian, and Beulah Richards, an occasional domestic and mother of ten children, including two who died in infancy. Wilder’s paternal grandparents, James and Agnes Wilder, were born in slavery and married on 25 April 1856 in Henrico County, Virginia, north of Richmond. They were later sold separately, and on Sundays, James would travel unsupervised to neighboring Hanover County to visit his wife and children. According to family lore, he was so highly regarded that if he returned late, the overseer would feign punishment by beating on a saddle. Agnes Wilder, a house servant, learned to read while overhearing the lessons of a handicapped child for whom she cared. Less is known of the origins of Wilder’s mother. She was raised by a grandmother and aunt in Richmond after her mother and stepfather died. Her father’s identity is unknown.

Douglas (later called Doug by non-family members) was the next to youngest of the Wilder children and one of only two boys who survived. He was named for FREDERICK DOUGLASS, the fiery abolitionist, and PAUL LAURENCE DUNBAR, the contemplative poet. He grew up in what the family describes as “gentle poverty,” surrounded by sisters and as the apple of his mother’s eye. Clever and high-spirited, the young Douglas shined shoes, hawked newspapers, and teased the family that “some rich people left me here, didn’t they?” “They’re coming back for me, aren’t they?” he would ask (Baker, 8). As a youth in segregated Richmond, Douglas had few associations with whites, other than as an elevator boy in a downtown office building and, while in college, as a waiter at private country clubs and downtown hotels.

Shortly after graduating in 1951 from Virginia Union University with a degree in chemistry, Wilder was drafted into the U.S. Army. While serving in the Seventeenth Infantry Regiment’s first battalion during the Korean War, he and a comrade captured twenty North Koreans holed up in a bunker, an action that won Corporal Wilder a Bronze Star. Back in the United States, Wilder began work as a technician in the state medical examiner’s office. In 1956 he enrolled in the Howard University law school, taking advantage of a state stipend encouraging African Americans to pursue advanced degrees out of state. Wilder married Eunice Montgomery in 1958, and after his graduation in 1959 they returned to Richmond, where his focus was less on dismantling segregation than on establishing a successful law practice. Over time he became known as one of the city’s leading criminal trial attorneys. That record was blemished somewhat by a 1975 reprimand from the Virginia Supreme Court for “inexcusable procrastination” in a car-accident case. Wilder apologized for and did not repeat the mistake.

In 1969 Wilder entered politics by winning a special election to a state senate seat against two white opponents in a majority-white district. Arriving as the first black member since Reconstruction of a body still dominated by rural white conservatives, Wilder made waves with his maiden floor speech denouncing the state song, “Carry Me Back to Ol’ Virginny.” Over the next several years he pursued a legislative agenda that was liberal by Virginia standards. He fought for fair-housing laws, pushed for a national holiday honoring MARTIN LUTHER KING Jr., and opposed the reinstatement of the death penalty. Although he later claimed to have done so primarily as a courtesy, he introduced legislation calling for statehood and voting rights for the District of Columbia, whose residents are largely African American. In 1978 Wilder’s marriage, which produced three children, ended in divorce.

A pivotal moment in Wilder’s rise came in 1982, when a moderate Democratic legislator, Owen B. Pickett, launched his campaign for a U.S. Senate seat by invoking the name and record of Harry Flood Byrd Jr., the retiring senator and the epitome of Old Virginia. Already angry at the treatment of black lawmakers in the 1982 assembly, Wilder threatened to run as an independent if Pickett did not withdraw. Governor Charles S. “Chuck” Robb and other Democratic kingpins calculated the odds of winning without the black vote and advised Pickett to exit. He did. Wilder had demonstrated the power of black voters in Virginia. When he announced his candidacy for lieutenant governor in 1985, the white establishment fretted, but no Democrat was willing to challenge his nomination. Benefiting from lackluster Republican opposition, Wilder ran a lively, shoestring campaign, hoarding his dollars for a final television blitz. He captured almost fifty-two percent of the vote, including support from an estimated forty-four percent of white Democrats who voted.

In the four years leading up to his 1989 race for governor, Wilder honed his trademark blend of contentiousness and charm. He quarreled with former governor Robb over politics and the present governor, Gerald Baliles. As the election approached and his chief rival for the Democratic nomination dropped out of the race, friction gave way to civility. Slight in stature, immaculately dressed, his mustache shaved, and his once bold Afro trimmed to a sedate silver cap, Wilder wooed audiences with an easy, engaging laugh and an increasingly centrist, nonthreatening message. He declined offers from JESSE JACKSON and other nationally prominent black politicians to travel to Virginia to campaign, and he deliberately avoided references to race and the historic nature of his campaign. Wilder drew support from a broad network of social acquaintances, but as in past campaigns, he kept few confidantes, relying on a small circle of advisers whose members fell in and out of grace.

Perhaps the determining event of the governor’s campaign occurred on 5 July 1989, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Webster v. Reproductive Services that states could restrict abortions beyond the limits set in 1973. Wilder deftly framed the issue as a matter of personal freedom. He trusted the women of Virginia to make the proper individual choice, he said. Wilder’s opponent, former Republican Attorney General J. Marshall Coleman, attempted to soften his hard-line, antiabortion message adopted in order to win a three-way contest for the Republican nomination. But in public opinion polls, both campaigns saw women in the vote-rich Washington, D.C., suburbs swing to Wilder.

Entering the final weekend of the campaign, opinion polls showed Wilder leading Coleman by as much as eleven percentage points. As soon as the voting ended on election night, an exit survey taken by Mason-Dixon Opinion Research appeared to confirm that margin. The celebration began. But as the evening wore on, the “landslide” turned into a cliffhanger. Wilder won by 6,741 votes of a record 1,787,131 cast. As in previous American elections involving black candidates, it appeared that many voters simply lied when asked about their vote.

In office Wilder encountered an unexpected $1.4 billion budget shortfall. By his second year, revenues lagged further. Rather than raise taxes, the option adopted by almost every other state during the recession of the early 1990s, Wilder instituted across-the-board spending cuts, laid off state workers, canceled salary increases, and insisted on holding the line on taxes. He pushed also for creation of a “rainy-day fund” to help tide the state over in future economic crises. His managing of the economic crisis was widely applauded, particularly after Virginia was cited twice in a row by Financial World magazine as the nation’s best managed state.

Wilder also won acclaim for the passage of legislation limiting guns sales in Virginia to one per month, thereby halting extensive gun running from Virginia to the northeast, and for extensive appointments of African Americans to prominent government posts. Less lauded was his 1991 bid for the Democratic presidential nomination, a campaign that alienated many Virginia voters before his voluntary withdrawal and during which he engaged in public spats with Robb and other prominent Democrats, including some members of the legislative black caucus. An article in U.S. News & World Report stated that “Virginia’s governor is capable of transcendent, triumphal moments and of astonishing pettiness” (13 May 1991).

Prohibited by the Virginia constitution from seeking more than one consecutive gubernatorial term, Wilder left office in January 1994. That spring he mounted a brief, independent run for Robb’s U.S. Senate seat. Both money and support lagged, and Wilder withdrew. Out of office, he conducted a radio call-in show, held a distinguished professorship at Virginia Commonwealth University, and pursued various personal interests, including plans for the creation of a national slavery museum. If his later career did not match expectations prompted by his 1989 election, he nonetheless retained the distinction at the arrival of the twenty-first century of being the only black man yet elected to the high honor of governor of an American state.

Wilder’s papers are housed at the L. Douglas Wilder Library at Virginia Union University and at the Library of Virginia, both in Richmond, Virginia.

Baker, Don. Wilder: Hold Fast to Dreams (1989).

Edds, Margaret. Claiming the Dream: The Victorious Campaign of Douglas Wilder of Virginia (1990).

Jeffries, Judson L. Virginia’s Native Son: The Election and Administration of Governor L. Douglas Wilder (2002).

Yancey, Dwayne. When Hell Froze Over: The Story of Doug Wilder: A Black Politician’s Rise to Power in the South (1990).

—MARGARET E. EDDS

WILKINS, J. ERNEST, JR.

WILKINS, J. ERNEST, JR.(27 Nov. 1923–), mathematician and engineer, was born in Chicago, the son of J. Ernest Wilkins, a prominent lawyer, and Lucile Beatrice Robinson, a school teacher with a master’s degree. Wilkins developed an intense interest in mathematics at an early age, and with the encouragement and support of his parents and a teacher at Parker High School in Chicago, he was able to accelerate his education and finish high school at the age of thirteen. After graduation, he was immediately accepted by the University of Chicago, where he was the youngest student ever admitted by that institution. Within five years, Wilkins received three degrees in Mathematics, a BA in 1940, an MS in 1941, and a PhD in 1942. He was also inducted into Phi Beta Kappa in 1940 and Sigma Xi, the Scientific Research Society, in 1942. While at the university, he was university table tennis champion for three years and won the boys’ state championship in 1938.

After earning his PhD from the University of Chicago, Wilkins received a Rosenwald Fellowship to carry out postdoctoral research at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey. During his stay, from October 1942 to December 1942, he worked on four papers. All were published within one year, with three appearing in the Duke Mathematical Journal and one in Annals of Mathematics.

In January 1943 Wilkins began teaching at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, where he had accepted a position as instructor of freshmen mathematics. However, in March 1944 he was recruited to work in the Metallurgical Laboratory at the University of Chicago as part of the Manhattan Project, the United States’ program to develop an atomic bomb. At the laboratory, he was given the title of “Associate Physicist” rather than “Mathematician,” a designation that allowed him to receive a higher salary. Wilkins worked under Eugene Wigner, who directed the Theoretical Physics Group, which provided the theoretical basis for the design of the Hanford, Washington, fission reactor. Wilkins’s duties consisted of applying his expertise in mathematics to help resolve various issues related to the understanding and design of reactors. During his stay at the Metallurgical Laboratory, Wilkins made several major contributions to the field of nuclear-reactor physics. It was in his Manhattan District reports that the concepts now referred to as the Wilkins effect, and the Wigner-Wilkins and Wilkins spectra for thermal neutrons, were developed and made quantitative.

At the completion of his duties at the Metallurgical Laboratory, Wilkins accepted a position as mathematician in the Scientific Instrument Division of the American Optical Company in Buffalo, New York. There he worked on the design of lenses for microscopes and ophthalmologic instruments. His research on “the resolving power of a coated objective” was published in the Journal of the Optical Society of America (1949, 1950), and was the first of a long series of publications, extending over four decades, on various problems related to apodization—methods that can be used to improve the resolving power of an optical system. In addition to the solution of several specific problems, Wilkins brought to the field of apodization a certain mathematical rigor, whose absence left many earlier results suspect.

On 22 June 1947 Wilkins married Gloria Louise Stewart; they had two children. Gloria Wilkins died in 1980. In May 1950 Wilkins moved to White Plains, New York, to accept the position of senior mathematician at the United Nuclear Corporation. After accepting a series of increasing managerial responsibilities, he became manager of the Research and Development Division, a group of about thirty individuals in mathematics, physics, chemistry, and metallurgy doing contract work for the Atomic Energy Commission in the areas of theoretical reactor physics and shielding. Wilkins developed and applied a variety of mathematical tools to problems in these fields, and some of his methods are now presented in the standard textbooks. In addition, his work with H. Goldstein on the transport of gamma rays through various materials was the standard reference for many years and is still cited in the current literature.

Although Wilkins’s work required him to provide mathematical support to the engineering staff, he discovered that many of them did not approach him for aid until their projects were substantially complete, often resulting in cost overruns. Wilkins concluded that his colleagues might respond better if he were a fellow engineer, and in 1953 he entered the Department of Mechanical Engineering at New York University. He graduated in 1957 with a BME magna cum laude and in 1960 received an MME degree. As he had hoped, his engineering colleagues at United Nuclear Corporation greatly increased their early consultations with him.

In September 1960 Wilkins accepted a position at the General Atomic Company in San Diego, California, as assistant chair of the Theoretical Physics Department. Shortly thereafter, he was promoted to assistant director of the John Jay Hopkins Laboratory, followed by further promotions to director of the Defense Science and Engineering Center and director of Computational Research. His managerial responsibilities included making sure that safety concerns were being treated seriously, insuring the progress of various technical projects, and providing both technical and policy advice to his administrative superiors. Particular programs included work on thermoelectricity, the design of high-temperature gas-cooled nuclear reactors, plasma physics as it relates to fusion reactors, and Project ORION, a program exploring the use of nuclear power to propel rockets.

In March 1970 Wilkins accepted a position at Howard University in Washington, D.C., as Distinguished Professor of Applied Mathematics and Physics. During his stay at Howard he supervised seven MS theses and four PhD dissertations. Wilkins had become a member of the American Nuclear Society in 1955; his increasing participation in the activities of the organization and his international prominence in several areas of mathematics and engineering led to his selection as national president in 1974–1975. In 1976 he was inducted into the National Academy of Engineering. The citation for this honor reads, “Peaceful application of atomic energy through contributions to the design and development of nuclear reactions.”

In September 1976 Wilkins took a sabbatical leave from Howard University to go to the Argonne National Laboratory in Argonne, Illinois. As a visiting scientist, he provided mathematics consultation in reactor physics and engineering. He also continued his own research interests in apodization and “a variational problem in Hilbert space.” Before Wilkins could return to Howard, he received an offer to return to industry as vice president and associate general manager for Science and Engineering at EG and G Idaho, Inc., in Idaho Falls, Idaho. He accepted this responsibility and began work in March 1977, officially resigning from the faculty at Howard in 1978. In 1978 he was promoted to deputy general manager for Science and Engineering, but he continued his position as vice president, with the responsibility of insuring the high quality of work and of representing the company in its dealings with the U.S. Department of Energy and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

In 1984 Wilkins retired from EG and G Idaho and returned to Argonne National Laboratory as a Distinguished Argonne Fellow. That summer he married Maxine G. Malone, who died in 1997; they had no children. At the completion of his stay at Argonne in May 1985, Wilkins went into full retirement. However, he continued to work as a consultant and adviser to a number of technical companies, professional organizations, and universities. It was during this period that Wilkins initiated a new area of research concerned with the real zeros of random polynomials, published in the Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society (1988, 1991).

Wilkins’s retirement ended in 1990 when he accepted the position of Distinguished Professor of Mathematics and Mathematical Physics at Clark Atlanta University in Atlanta. A major factor influencing this decision was the opportunity to collaborate with Albert Turner Bharucha-Reid, an internationally recognized mathematician, on random polynomials. Unfortunately, Bharucha-Reid died before Wilkins arrived at the university, but Wilkins continued his research, publishing over the next decade five fundamental papers on the mean number of real zeros for random hyperbolic, the French mathematician Adrien-Marie Legendre, and trigonometric polynomials. During this period he also supervised eleven MS theses in the Department of Mathematical Sciences. Wilkins retired from Clark Atlanta University in August 2003, and in September he married Vera Wood Anderson in Chicago.

J. Ernest Wilkins Jr.’s distinguished career as a research mathematician and engineer has lasted almost six decades, and his contributions to research and management have been recognized by a large number of honors and awards received throughout his life.

A complete copy of J. Ernest Wilkins Jr.’s curriculum vita, along with other bibliographic materials, is in the Special Collections of the Atlanta University Center of the Woodruff Library in Atlanta.

Donaldson, James. “Black Americans in Mathematics” in A Century of Mathematics in America, Part III (1989): 449–469.

Newell, V. K., ed. Black Mathematicians and Their Works (1980).

“Phi Beta Kappa at 16.” The Crisis, Sept. 1940, 288.

Tubbs, Vincent. “Adjustment of a Genius.” Ebony, Feb. 1958: 60–67.

—RONALD E. MICKENS

WILKINS, ROY

WILKINS, ROY(30 Aug. 1901–8 Sept. 1981), reporter and civil rights leader, was born Roy Ottaway Wilkins in St. Louis, Missouri, the son of William DeWitte Wilkins, a brick kiln worker, and Mayfield Edmundson. Upon his mother’s death in 1905, Wilkins was sent with his brother and sister to St. Paul, Minnesota, to live with their aunt and uncle, Elizabeth and Sam Williams, because his mother worried that her husband could not handle raising their three children and would send them back to Mississippi. The family had fled Mississippi after an incident in which William had beaten a white man over a racial insult.

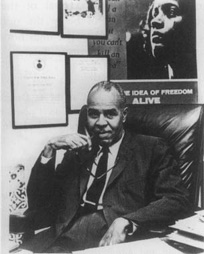

Roy Wilkins in the national headquarters of the NAACP in New York City in 1963. Library of Congress

Wilkins grew up in a middle-class household in a relatively integrated neighborhood. A porter who oversaw operations in the personal car of the chief of the Northern Pacific Railroad, Sam Williams taught Wilkins the virtue of education. Stressing the importance of faith, Sam and Elizabeth also regularly took Wilkins to the local African Methodist Episcopal Church. He developed an interest in writing in high school and then went on to the University of Minnesota, where he became the first black reporter for the school’s newspaper. Wilkins also served as editor of the Saint Paul Appeal, a weekly African American paper, and was an active member of the city’s NAACP branch.

After graduating from college with honors in 1923, Wilkins became a reporter with the Kansas City Call. He covered the NAACP’s Midwestern Race Relations Conference and was deeply inspired by JAMES WELDON JOHNSON’S message stressing the need for African Americans to fight for constitutional rights. Wilkins was outraged over the widespread racism in Kansas City in housing, public accommodations, education, law enforcement, and employment, but his middle-class values of thrift and hard work also led him to look disdainfully at blacks who behaved in ways that affirmed negative white stereotypes. “A lot of the things we suffered came as wrapped, perfumed presents from ourselves,” he later wrote (Wilkins, 73). Wilkins soon became secretary of the Kansas City branch of the NAACP, and in 1929 he married Aminda Badeau, a social worker who came from a prominent St. Louis family. The couple had no children.

Wilkins’s writing and NAACP work soon caught the attention of WALTER WHITE, the executive secretary of the national organization, and in 1931 White persuaded Wilkins to move to New York to become his chief aide. His duties included writing, lecturing, raising money, and speaking out against racial injustice. When Will Rogers used a racial epithet four times in a radio broadcast, for example, Wilkins organized a nationwide effort to bombard the National Broadcasting Company with telegrams of protest. In 1932 he traveled to Mississippi to do an undercover investigation of the low pay and horrible working conditions suffered by African Americans working for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Wilkins’s findings encouraged Senator Robert Wagner of New York to hold hearings on the conditions, and as a result the workers received modest pay increases. In 1934 Wilkins became editor of the Crisis, the NAACP’s magazine, and brought changes to the periodical that boosted its financial position and broadened its coverage. W. E. B. DU BOIS, the magazine’s former editor, looked upon Wilkins and his changes with disdain, and the two would later clash over Du Bois’s growing radicalism. Throughout the 1930s and 1940s Wilkins also battled Communists within the NAACP. Holding a strong faith in America’s democratic promise, he disagreed profoundly with their philosophy and viewed them as politically harmful to the struggle for racial equality.

Upon Walter White’s death in 1955, Wilkins was unanimously selected as the new executive secretary of the NAACP, a post he would hold for twenty-two years. Wilkins strongly believed that working through the courts for legal changes and lobbying presidents and lawmakers in Congress for civil rights legislation offered the best way to effect lasting, significant improvements for African Americans. He regularly testified before Congress on behalf of legislation, met with every president from Harry Truman through Jimmy Carter, rallied NAACP branches and other progressive organizations to support various civil rights initiatives, and appeared before Democratic and Republican conventions to urge both parties to take strong stands for racial equality. Wilkins’s efforts helped produce such landmark federal laws as the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which outlawed segregation in public accommodations and employment discrimination; the Voting Rights Act of 1965; and the Fair Housing Act of 1968. Like many other civil rights leaders, Wilkins found President Lyndon Johnson to be a valuable ally. Conversely, he regularly criticized Dwight Eisenhower and John F. Kennedy for doing too little.

As direct-action protests became more prominent in the 1950s and early 1960s, Wilkins steadfastly held to his legalistic approach. He was initially skeptical about seminal protests, such as the Montgomery bus boycott and the 1963 March on Washington, though he ultimately supported them. Similarly, Wilkins and BAYARD RUSTIN urged the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) to accept President Johnson’s compromise offer of two at-large seats at the 1964 Democratic convention if they would moderate their demands for broader representation. The MFDP’s FANNIE LOU HAMER and ROBERT P. MOSES refused to compromise, however.

Fearing that civil rights protests might turn to violence and play into the hands of the Republican presidential candidate Barry Goldwater, a staunch conservative who had opposed the 1964 Civil Rights Act, Wilkins also organized an effort among several black leaders that summer to call for a moratorium on civil rights demonstrations until after the presidential election. Wilkins often criticized MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. and groups such as CORE and SNCC, because he doubted that direct action would lead to meaningful change. “When the headlines are gone, the issues still have to be settled in court,” he observed (Branch, 557). Wilkins’s views also reflected his personal jealousy over the growing popularity of such groups and King. “The other organizations,” he angrily commented, “furnish the noise and get the publicity while the NAACP furnishes the manpower and pays the bills” (Branch, 831). Wilkins especially feared that King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference would erode the NAACP’s financial and political strength in the South. Thus, though the two leaders often worked together, they maintained an uneasy relationship throughout the 1960s. King believed the NAACP was often too timid, while Wilkins saw King as a self-promoter. Wilkins distanced himself and the NAACP from King as the SCLC leader grew more critical of the Vietnam War.

Wilkins came under sharp attack from more radical African Americans in the mid- to late 1960s for his unwavering faith in integration, willingness to work with white allies, and confidence in American institutions. Critics also alleged that the NAACP was too timid and had no program to help African Americans economically. Wilkins bristled at these charges and fired back that Black Power was “the father of hatred and the mother of violence” (Fairclough, 320). Younger African Americans sympathetic to Black Power, Wilkins insisted, were “unfair, ungrateful, and forgetful” regarding NAACP accomplishments (New York Times, 9 Sept. 1981). One radical group, the Revolutionary Action Movement, even hatched plans to assassinate Wilkins in 1967, though no attempt on his life was carried out, because police raided the group’s headquarters and broke up the plot.

At the same time he faced these conflicts with external rivals, Wilkins battled critics within the NAACP. A group of junior NAACP board members known as the Young Turks challenged Wilkins’s positions on economic issues, race riots, and the NAACP’s endorsement of Johnson in the 1964 presidential election. Supporting Johnson contradicted the organization’s longstanding policy of nonpartisanship, but Wilkins saw the right-wing Republican Goldwater as a threat to recent civil rights advances. Critics also believed that Wilkins wielded too much power within the organization. The Young Turks endorsed structural changes that would give more power to local branches and would strip some authority from the national leadership. They first made their case at the NAACP’s annual convention in 1965, when they came within one vote of removing Wilkins from the leadership post. The feud lasted for three years. By 1968, however, Wilkins had firmly consolidated his power and put down the rebellion. His means included co-opting some of the Turks’ agenda and, at the 1968 NAACP convention in Atlantic City, calling in law enforcement officials to keep order, turning off microphones and lights when some of the Turks attempted to speak, and tabling the dissenters’ proposals quickly, with little or no debate.

Wilkins continued to advocate for laws and programs to improve black life in education, housing, employment, health care, and other areas throughout the 1970s. He sharply criticized Republican presidents Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford over school desegregation, busing, and voting rights, but failing health slowed his activities somewhat. In 1969 he had suffered a second bout with cancer. Ill health forced him to retire from the NAACP in 1977, when he was replaced by Benjamin Hooks. Four years later, Wilkins died from kidney failure at New York University Medical Center. Upon hearing of Wilkins’s death, JESSE JACKSON observed that he was “a man of integrity, intelligence, and courage who, with his broad shoulders, bore more than his share of responsibility for our and the nation’s advancement” (New York Times, 9 Sept. 1981).

Roy Wilkins’s papers are housed at the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Wilkins, Roy, with Tom Mathews. Standing Fast: The Autobiography of Roy Wilkins (1982).

Branch, Taylor. Parting the Waters: America in the King Years, 1954–1963 (1988).

Eick, Gretchen Cassel. Dissent in Wichita: The Civil Rights Movement in the Midwest, 1954–72 (2001).

Fairclough, Adam. To Redeem the Soul of America: The Southern Christian Leadership Conference and Martin Luther King, Jr. (1987).

Obituary: New York Times, 9 Sept. 1981.

—TIMOTHY N. THURBER

WILLIAMS, BERT

WILLIAMS, BERT(12 Nov. 1874–4 Mar. 1922), and GEORGE WALKER (1873–6 Jan. 1911), stage entertainers, were born, respectively, Egbert Austin Williams in Nassau, the Bahamas, and George Williams Walker in Lawrence, Kansas. Williams was the son of Frederick Williams Jr., a waiter, and Julia Monceur. Walker was the son of “Nash” Walker, a policeman; his mother’s name is unknown. Williams moved with his family to Riverside, California, in 1885 and attended Riverside High School. Walker began performing “darkey” material for traveling medicine shows during his boyhood and left Kansas with Dr. Waite’s medicine show. In 1893 Williams and Walker met in San Francisco, where they first worked together in Martin and Selig’s Minstrels.

To compete in the crowded field of mostly white blackface performers, “Walker and Williams,” as they were originally known, subtitled their act “The Two Real Coons.” Walker developed a fast-talking, city hustler persona, straight man to Williams’s slow-witted, woeful bumbler. Williams, who was light-skinned, used blackface makeup on stage, noting that “it was not until I was able to see myself as another person that my sense of humor developed.” An unlikely engagement in the unsuccessful Victor Herbert operetta The Gold Bug brought Williams and Walker to New York in 1896, but the duo won critical acclaim and rose quickly through the ranks of vaudeville, eventually playing Koster and Bial’s famed New York theater. During this run they added a sensational cakewalk dance finale to the act, cinching popular success. Walker performed exceptionally graceful and complex dance variations, while Williams clowned through an inept parody of Walker’s steps. Aida Reed Overton, who later become a noteworthy dancer and choreographer in her own right, was hired as Walker’s cakewalk partner in 1897 and became his wife in 1899. They had no children. The act brought the cakewalk to the height of its popularity, and Williams and Walker subsequently toured the eastern seaboard and performed a week at the Empire Theatre in London in April 1897.

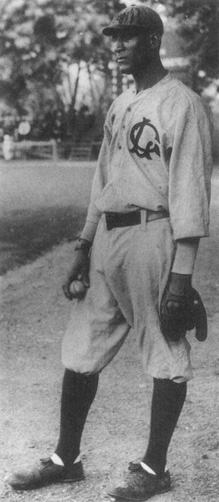

Bert Williams and George Walker performed in WILL MARION COOK’s musical In Dahomey on the lawn of Buckingham Palace in 1902. Museum of London

Vaudeville typically used stereotyped ethnic characterizations as humor, and Williams and Walker developed a “coon” act without peer in the industry. For the 1898 season, the African American composer WILL MARION COOK and the noted poet PAUL LAURENCE DUNBAR created Senegambian Carnival for the duo, the first in a series of entertainments featuring African Americans that eventually played New York. A Lucky Coon (1898), The Policy Players (1899), and Sons of Ham (1900) were basically vaudeville acts connected by Williams and Walker’s patter. In 1901 they began recording their ragtime stage hits for the Victor label. Their popularity spread, and the 18 February 1903 Broadway premiere of In Dahomey was considered the first fully realized musical comedy performed by an all-black company. In 1900 Williams had married Charlotte Louise Johnson; they had no children.

Williams and Walker led the In Dahomey cast of fifty as Shylock Homestead and Rareback Pinkerton, two confidence men out to defraud a party of would-be African colonizers. Its three acts included a number of dances, vocal choruses, specialty acts, and a grand cakewalk sequence. Critics cited Williams’s performance of “I’m a Jonah Man,” a hard-luck song by Alex Rogers, as a high point of the hit show. In Dahomey toured England and Scotland, with a command performance at Buckingham Palace arranged for the ninth birthday of King Edward VII’s grandson David. The cakewalk became the rage of fashionable English society, and company members worked as private dance instructors both abroad and when they returned home.

Williams composed more than seventy songs in his lifetime. “Nobody,” the most famous of these, was introduced to the popular stage in 1905:

When life seems full of clouds and rain, And I am filled with naught but pain, Who soothes my thumping, bumping brain? Nobody!

The sense of pathos lurking behind Williams’s plaintive delivery was not lost on his audience. Walker gained fame performing boastful, danceable struts, such as the 1906 “It’s Hard to Find a King Like Me” and his signature song, “Bon Bon Buddie, the Chocolate Drop,” introduced in 1907. During this period Williams and Walker signed their substantial music publishing rights with the black-owned Attucks Music Publishing Company.

Walker, who was more business-minded than Williams, controlled production details of the 1906 Abyssinia and the 1907 Bandanna Land. Walker demanded that these “all-Negro” productions play only in first-class theaters. His hard business tactics worked, and Williams and Walker played several theaters that had previously barred black performers. In 1908, at the height of their success, the duo were founding members of The Frogs, a charitable and social organization of black theatrical celebrities. Other members included composers Bob Cole and J. Rosamond Johnson, bandleader JAMES REESE EUROPE, and writer/directors Alex Rogers and Jesse Shipp.

During the tour of Bandanna Land, Walker succumbed to general paresis, an advanced stage of syphilis. He retired from the stage in February 1909. Aida Walker took over his songs and dances, and the book scenes were rewritten for Williams to play alone. Walker died in Islip, New York.

Williams continued doing blackface and attempted to produce the 1909 Mr. Lode of Koal without Walker. His attention to business details languished, and the show failed. Williams’s performances, however, received significant critical praise, and he gained stature as “an artist of pantomime” and “a comic genius.” In 1910 he joined Florenz Ziegfeld’s Follies. He told the New York Age (1 Dec. 1910) that “the colored show business—that is colored musical shows—is at the low ebb just now. I reached the conclusion last spring that I could best represent my race by doing pioneer work. It was far better to have joined a large white show than to have starred in a colored show, considering conditions.”

Williams was aware of the potential for racial backlash from his white audience and insisted on a contract clause stating that he would at no time appear on stage with any of the scantily clad women in the Follies chorus. His celebrity advanced, and he became the star attraction of the Follies for some eight seasons, leaving the show twice, in 1913 and 1918, to spend time with his family and to headline in vaudeville. His overwhelming success prompted educator BOOKER T. WASHINGTON to quip, “Bert Williams has done more for the race than I have. He has smiled his way into people’s hearts. I have been obliged to fight my way.”

An Actor’s Equity strike troubled Ziegfeld’s 1919 edition of the Follies, and Williams, who had never been asked or allowed to join the union because of his African ancestry, left the show. In 1920 he and Eddie Cantor headlined Rufus and George Lemaire’s short-lived Broadway Brevities. In 1921 the Shuberts financed a musical, Under the Bamboo Tree, to star Williams with an otherwise all-white cast. The show opened in Cincinnati, Ohio, but in February 1922 Williams succumbed to pneumonia, complicated by heart problems, and died the next month in New York City.

Although Williams’s stage career solidified the stereotype of the “shiftless darkey,” his unique talent at pantomime and the hard work he put into it was indisputable. In his famous poker game sketch, filmed in the 1916 short A Natural Born Gambler, Williams enacted a four-handed imaginary game without benefit of props or partners. His cache of comic stories, popularized in his solo vaudeville and Ziegfeld Follies appearances, were drawn largely from African American folk humor, which Williams and Alex Rogers duly noted and collected for their shows. Williams collected an extensive library and wrote frequently for the black press and theatrical publications.

The commercial success of Williams and Walker proved that large audiences would pay to see black performers. Tall and light-skinned Williams, in blackface and ill-fitting tatters, contrasted perfectly with short, dark-skinned, dandyish Walker. Their cakewalks revived widespread interest in African American dance styles. Their successful business operations, responsible for a “$2,300 a week” payroll in 1908, encouraged black participation in mainstream show business. The Chicago Defender (11 Mar. 1922) called them “the greatest Negro team of actors who ever lived and the most popular pair of comedy stars America has produced.”

Allen, Woll. Black Musical Theatre—From Coontown to Dreamgirls (1989).

Charters, Ann. Nobody: The Story of Bert Williams (1970).

JOHNSON, JAMES WELDON. Black Manhattan (1930).

Rowland, Mabel. Bert Williams: Son of Laughter (1923).

Sampson, Henry T. Blacks in Blackface: A Source Book on Early Black Musical Shows (1980).

Smith, Eric Ledell. Bert Williams: A Biography of the Pioneer Black Comedian (1992).

Obituaries: New York Times, 8 Jan. 1911 (Walker) and 5 Mar. 1922 (Williams).

—THOMAS F. DEFRANTZ

WILLIAMS, CATHAY

WILLIAMS, CATHAY(Sept. 1844–?), cook, laundress, and Buffalo Soldier, was born into slavery in Independence, Missouri. Nothing is known of her parents, except that her father was reported to be a free black man. At some point in her early childhood, she went with her master’s family to a farm near Jefferson City, where she toiled as a house servant until the start of the Civil War.

Probably in the summer of 1861, when she was nearly seventeen years old, Williams fled the plantation and joined the large group of escaped and newly freed slaves seeking the protection of Union troops occupying Jefferson City. Within months she was pressed into service as a laundress and cook for a Union regiment, possibly the Eighth Indiana Infantry. She maintained that position for nearly two years, accompanying the troops on campaigns in Missouri and Arkansas. In the summer of 1863 Williams found employment as a government cook in Federal-controlled Little Rock. Within a year she was a regimental laundress and cook again, purportedly working throughout the Red River campaign in Louisiana before being sent east, where she said she obtained employment as “cook and washer woman” for the staff of General Philip Sheridan during the second Shenandoah Valley Campaign in Virginia. By January 1865 Williams was back with her old regiment, traveling with them to Savannah, Georgia, until the end of the war.

After the cessation of hostilities, Williams managed to return to Missouri to reunite with her family. In November 1866, in the company of a male cousin and a “particular friend,” she disguised herself as a man and enlisted in the U.S. Army in St. Louis under the alias of William Cathey. Her reasons for doing so have never been clearly delineated. She may have viewed the military as an opportunity for a decent livelihood and a semblance of respect, since as a black woman in postwar Missouri her economic prospects were dim. Her years with the Union army undoubtedly made the military seem a familiar place in which to stake her future. Or perhaps her motivation was a strong desire to accompany her cousin and her friend.

Army regulations of the time forbade the enlistment or commissioning of women as soldiers, but since recruiters did not seek proof of identity and because army surgeons often failed to fully examine enlistees, it was not very difficult for women to infiltrate the military. During the Civil War, for example, hundreds of women pretended to be men and served in both the Union and Confederate armies. Williams, however, holds the distinction of being the only known female Buffalo Soldier, and the only documented African American woman to serve in the U.S. Regulars in the nineteenth century. At least three black women served as soldiers in the Civil War: Lizzie Hoffman and another unidentified woman in the U.S. Colored Troops, and Maria Lewis, passing as a white man, in a New York cavalry regiment.

Williams, using the name William Cathey, informed the recruiting officer that she was twenty-two years old and a cook by occupation. Her enlistment papers reveal that she was illiterate at the time of her induction. The recruiting officer described Private William Cathey as five feet, nine inches tall, with black eyes, black hair, and black complexion. She was one of the tallest soldiers in her company. An army surgeon reportedly examined her upon enlistment and determined that she was fit for duty. The exam was obviously a farce or incomplete, as neither the surgeon nor the recruiter realized that she was a woman. Assigned to Company A of the segregated Thirty-eighth U.S. Infantry, Private Cathey did not have an illustrious or exciting army career. She was an average soldier, never singled out for praise or punishment, and, apparently, neither distinguished nor disgraced herself. Opinions held of Private Cathey by her fellow soldiers and officers are unknown.

From her enlistment until February 1867, Williams was stationed at Jefferson Barracks, except for one visit to a St. Louis hospital for treatment of an undocumented illness. By April 1867 Private Cathey and her company had marched to Fort Riley, Kansas, where she and fifteen others were described as “ill in quarters” for two weeks. In June 1867 her company arrived at Fort Harker, Kansas, and the following month they arrived at Fort Union, New Mexico, after a march of 536 miles. By October the company was encamped at Fort Cummings, New Mexico. It appears that Private Cathey withstood the marches as well as any man in her unit, and although she participated in her share of soldierly obligations, the company never engaged the enemy or saw any direct combat while she was a member. In January 1868 her health began to deteriorate, and she was hospitalized for rheumatism that month and again in March. In June the company marched for Fort Bayard, New Mexico, where she was admitted into the hospital in July and diagnosed with neuralgia, a catch-all term for any acute pain of the nervous system. She did not report back to duty for a month.

On 14 October 1868 Private Cathey and two others in Company A were discharged from the Thirty-eighth Infantry on a surgeon’s certificate of medical disability. She had served her country for just less than two years. Although Cathey’s discharge papers do not indicate that the surgeon was aware of her true sex, Williams later related that she grew tired of being a soldier and eventually confessed her true identity to obtain release from the military. Indeed, none of the records of the Thirty-eighth Infantry—including carded medical records, enlistment papers, and the muster rolls and returns of Company A, Thirty-eighth U.S. Infantry—reveal any awareness of a woman in the ranks.

Upon resuming civilian life, she traveled to Fort Union and worked as a cook until some time in 1870, when she moved to Pueblo, Colorado, and worked as a laundress for two years. She next moved to Las Animas County, Colorado, staying for a year, again working as a laundress. She finally settled, more or less permanently, in Trinidad, Colorado, making her living as a laundress, seamstress, and nurse. In 1875 Williams told her life story to a St. Louis journalist traveling in Colorado, who described her as “tall and powerfully built, black as night, muscular looking.” The full newspaper article published the following year remains the only written story of her life told in her own voice. In the mid-1880s Williams moved to Raton, New Mexico, where she may have operated a boarding house. By 1889 she was back in Trinidad, hospitalized for nearly a year and a half with an undisclosed illness.

Williams was probably indigent when she left the hospital, so in June 1891 she petitioned for an “invalid pension” based upon her military service. Her sworn application gave her age as forty-one, and she declared that she was the same William Cathey who served as a private in the Thirty-eighth Infantry. She produced her original discharge certificate as proof. She claimed she was suffering deafness, contracted in the army; she referred to her rheumatism; and she declared she was eligible for the government pension because she could no longer sustain herself by manual labor. A supplemental declaration, filed the following month, contended that she had contracted smallpox at St. Louis in 1868, and, while still recovering, swam the Rio Grande on the way to New Mexico. She believed that the combined effects of smallpox and exposure led to her deafness. All of her pension papers were signed by her, as she had learned to read and to write since her time in the army more than two decades earlier.

On 8 September 1891 a medical doctor in Trinidad, commissioned by the Pension Bureau, examined Williams. Charged with providing a thorough examination of the patient and a complete description of her physical condition, the doctor described her as five feet, seven inches tall, 160 pounds, and “stout.” He reported that she was not deaf and he could find no evidence of rheumatism. Most horrifying, the doctor reported that all her toes on both feet had been amputated, and she could walk only with the aid of a crutch, but he provided no explanation of the cause of amputation. Other than the loss of her toes, the doctor stated she was in good general health and gave his opinion as “nil” on a disability rating. In February 1892 the Pension Bureau rejected her claim for an invalid pension, and Williams never received any government assistance. The bureau rejected her claim on medical grounds, but it never questioned her identity. No one appeared to doubt that William Cathey of the Thirty-eight Infantry and Cathay Williams of Trinidad were the same person.

Nothing definite is known of Williams after her pension case closed, although it is believed that she died before 1900. Where and how she lived, the date and place of her death, and her final resting place are undetermined.

Records pertaining to Cathay Williams’s military service as Private William Cathey can be found at the National Archives in Washington, D.C., in Record Group 94; and her pension application file (SO 1032593), in Record Group 15.

Tucker, Phillip Thomas. Cathy Williams: From Slave to Female Buffalo Soldier (2002).

“Cathay Williams Story.” St. Louis Daily Times, 2 Jan. 1876.

—DE ANNE BLANTON

WILLIAMS, DANIEL HALE

WILLIAMS, DANIEL HALE(18 Jan. 1856–4 Aug. 1931), surgeon and hospital administrator, was born in Hollidaysburg, south central Pennsylvania, the son of Daniel Williams Jr. and Sarah Price. His parents were black, but Daniel himself, in adult life, could easily be mistaken for being white, with his light complexion, red hair, and blue eyes.

Williams’s father did well in real estate but died when Daniel was eleven, and the family’s financial situation became difficult. When Williams was seventeen, he and a sister, Sally, moved to Janesville, Wisconsin. Here Williams found work at Harry Anderson’s Tonsorial Parlor and Bathing Rooms. Anderson took the two of them into his home as family and continued to aid Williams financially until Williams obtained his MD.

Medicine had not been Williams’s first choice of a career; he had worked in a law office after high school but had found it too quarrelsome. In 1878 Janesville’s most prominent physician, Henry Palmer, took Williams on as an apprentice. Williams entered the Chicago Medical College in the fall of 1880 and graduated in 1883. He opened an office on Chicago’s South Side and treated both black and white patients.

Late in 1890 the Reverend Louis Reynolds, a pastor on the West Side, asked Williams for advice about his sister, Emma, who had been turned down at several nursing schools because of her color. As a result Williams decided to start an interracial hospital and a nursing school for black women. He drew on black and white individuals and groups for financial support. Several wealthy businessmen, such as meat-packer Philip D. Armour and publisher Herman H. Kohlsaat, made major contributions to the purchase of a three-story building at Dearborn and Twenty-ninth Street and its remodeling into a hospital with twelve beds. Provident Hospital and Training School Association was officially incorporated on 23 January 1891 and opened for service on 4 May of that year. The Training School received 175 applicants for its first class, and Williams selected seven for the eighteen-month course.

Provident had both white and black patients and staff members, although the lack of suitably qualified black physicians led to some problems. Williams appointed black physicians and surgeons who had obtained their medical degrees from schools such as the Rush Medical College and his own alma mater and who, in addition, had suitable experience. However, he had to deal diplomatically with some leaders of the black community who were pushing the appointment of young George Cleveland Hall, who had a degree from an eclectic school and only two years of experience (mostly in Chicago’s red light district). Hall (and his equally aggressive wife) never forgave Williams for this early judgment to oppose Hall’s appointment.

The hospital soon became overcrowded, but many donations—again including major contributions from Armour and Kohlsaat—resulted in the construction of a new sixty-five-bed hospital at Dearborn and Thirty-sixth streets. The new Provident opened in late 1896.

In 1893 a longtime Chicago friend of Williams, Judge Walter Q. Gresham, recently named secretary of state by President Grover Cleveland, urged Williams to seek the position of surgeon in chief at Freedmen’s Hospital in Washington, D.C. This, Gresham pointed out, would bring Williams onto the national scene. Williams, believing that Provident was in good hands, finally agreed to Gresham’s suggestion and in 1894 was appointed to Freedmen’s where his predecessor, Charles B. Purvis, unhappy at being replaced and often with the aid of Hall, made life as difficult as possible for Williams.

Williams, nevertheless, accomplished much at Freedmen’s. He reorganized the staff interracially, created an advisory board of prominent physicians for both professional and political help, and founded a successful nursing school. Williams also began an internship program, improved relationships with the Howard University Medical School, and helped establish an interracial local medical society.

Williams also worked hard on the national scene and became one of the founders of the National Medical Association in 1895. Because at the time the American Medical Association did not accept black physicians, such a national organization was a necessary part of the educational and professional growth for black healthcare givers. In 1895 Williams turned down the presidency but did become vice president of the organization.

With the election in 1896 of a new U.S. president, the control of Freedmen’s became involved in partisan congressional hearings. These were sufficiently upsetting for Williams, but then William A. Warfield, one of Williams’s first interns at Freedmen’s, accused his chief, before the hospital’s board of visitors, of stealing hospital supplies. Although the congressional hearings came to no conclusion and the board of visitors exonerated Williams, he had become soured on Washington and resigned early in 1898.

In April 1898 Williams married Alice Johnson in Washington, D.C. The couple moved to Chicago, and Williams returned to his old office. There the Halls continued to undermine the Williamses’ professional and social lives. Hall finally forced Williams to resign from Provident in 1912 because the latter had become an associate attending surgeon at St. Luke’s Hospital and was, therefore, “disloyal” to Provident. That this was a trumped-up charge was apparent from the fact that, since 1900, Williams had regularly had patients in up to five other hospitals at the same time.

National recognition, however, counterbalanced such sniping; in 1913 Williams was nominated to be a charter member of the American College of Surgeons, the first black surgeon to be honored in this manner. At the board of regents meeting to act on this, a surgeon from Tennessee objected because of the social implications in the South. After vigorous discussion, during which it was pointed out that “if you met him [Williams] on the street you would hardly realize that he is a Negro,” Williams was accepted.

As a surgeon, Williams is best known for his stitching of a stab wound to the pericardium of Jim Cornish, an expressman, on 9 July 1893. After Williams had realized that conservative care would not be sufficient for Cornish, he searched the medical literature for reports of surgery in this area. Finding none, he nevertheless decided to perform surgery. Cornish lived for fifty years after the operation. While strictly speaking not an operation on the heart itself, this was the first successful suturing of the pericardium on record.

Perhaps more important surgically was Williams’s successful suturing of a heavily bleeding spleen in July 1902, one of the earliest such operations in the United States. Williams also operated on many ovarian cysts, a condition that had not been believed to occur in black women. In 1901 he reported on his 357 such operations, almost equally divided between black and white patients.

Well aware of the lack of training opportunities available to black surgeons in the South, Williams readily accepted an invitation near the end of the century to be a visiting professor of clinical surgery at the Meharry Medical College in Nashville, Tennessee. He spent five or ten days there without pay each year for over a decade. He began operating in a crowded basement room, but by 1910 growing financial support for the college programs resulted in a separate hospital building with forty beds. Williams also operated and lectured at other schools and hospitals in the South.

In 1920 Williams built a summer home near Idlewild, Michigan, to which he and his wife moved. There Alice died of Parkinson’s disease a few years later, and Williams then succumbed to diabetes and a stroke.

Williams became known for his long and successful efforts for medical care and professional training for blacks, although much of his work was multiracial. His logically developed and pioneering surgery, especially on the pericardium and the spleen, increased the possibilities and scope of surgical action.

Beatty, William K. “Daniel Hale Williams: Innovative Surgeon, Educator, and Hospital Administrator,” Chest 60 (1971): 175–82.

Buckler, Helen. Daniel Hale Williams: Negro Surgeon (1954; repr. 1966).

—WILLIAM K. BEATTY

WILLIAMS, GEORGE WASHINGTON

WILLIAMS, GEORGE WASHINGTON(16 Oct. 1849–2 Aug. 1891), soldier, clergyman, legislator, and historian, was born in Bedford Springs, Pennsylvania, the son of Thomas Williams, a free black laborer, and Ellen Rouse. His father became a boatman and, eventually, a minister and barber, and the younger Williams drifted with his family from town to town in western Pennsylvania until the beginning of the Civil War. With no formal education, he lied about his age, adopted the name of an uncle, and enlisted in the United States Colored Troops in 1864. He served in operations against Petersburg and Richmond, sustaining multiple wounds during several battles. After the war’s end Williams was stationed in Texas, but crossed the border to fight with the Mexican republican forces that overthrew the emperor Maximilian. He returned to the U.S. Army in 1867, serving with the Tenth Cavalry, an all-black unit, at Fort Arbuckle, Indian Territory. Williams was discharged for disability the following year after being shot through the left lung under circumstances that were never fully explained.

For a few months in 1869 Williams was enrolled at Howard University in Washington, D.C. But with an urgent desire to become a Baptist minister, he sought admission to the Newton Theological Institution in Massachusetts. Semiliterate and placed in the English “remedial” course at the outset, Williams underwent a remarkable transformation. He became a prize student as well as a polished writer and public speaker and completed the three-year theological curriculum in two years. In 1874, following graduation and marriage to Sarah Sterret of Chicago, Williams was installed as pastor of one of the leading African American churches of Boston, the Twelfth Baptist. A year later he went with his wife and young son (their only child) to Washington, D.C. There he edited the Commoner, a weekly newspaper supported by FREDERICK DOUGLASS and other leading citizens and intended to be, in Williams’s words, “to the colored people of the country a guide, teacher, defender, and mirror.” It folded after about six months of publication.

The West beckoned, and Williams moved in 1876 to Cincinnati, where he served as pastor of the Union Baptist Church through the end of the next year. Also engaged as a columnist for a leading daily newspaper, the Cincinnati Commercial, he contributed sometimes autobiographical pieces on cultural, racial, religious, and military themes. He spent what spare time he had studying law in the office of Judge Alphonso Taft, father of William Howard Taft. Even before passing the bar in 1881, Williams had become deeply immersed in Republican politics—as a captivating orator, holder of patronage positions, and, in 1877, an unsuccessful legislative candidate. In 1879 the voters of Cincinnati elected him to the Ohio House of Representatives, making Williams the first African American to sit in the state legislature. He served one term, during which he was the center of several controversies, ranging from the refusal of a Columbus restaurant catering to legislators to serve him to a furor in the African American community over his support for the proposed closing of a black cemetery as a health hazard. Williams’s effort to repeal a law against interracial marriage failed; he also supported a bill restricting liquor sales.

By this time Williams had developed an interest in history. In 1876 he delivered an Independence Day Centennial oration titled “The American Negro from 1776 to 1876.” While in the legislature, Williams made regular use of the Ohio State Library to collect historical information. After completing his stint as a lawmaker in 1881, he devoted his full attention to writing History of the Negro Race in America from 1619 to 1880: Negroes as Slaves, as Soldiers, and as Citizens. Based on extensive archival research, interviews, and Williams’s pioneering use of newspapers, and published in two volumes by G. P. Putnam’s Sons in 1882–1883, the work was the earliest extended, scholarly history of African Americans. Comprehensive in scope, it touched on biblical ethnology and African civilization and government but gave particular attention to blacks who served in America’s wars. Widely noticed in the press, Williams’s History of the Negro Race in America was, for the most part, well received as the first serious work of historical scholarship by an African American. Williams followed it in 1887 with another major historical work, A History of the Negro Troops in the War of the Rebellion, 1861–1865. Drawing on his own experiences (but also on the wartime records then being published for the first time), Williams wrote bitterly of the treatment of black soldiers by white northerners as well as by Confederates. Despite disadvantages, their conduct, in his opinion, was heroic, and he concluded that no troops “could be more determined or daring.” Though not as widely heralded as his earlier volumes, A History of the Negro Troops in the War of the Rebellion was generally well reviewed by the white and black press. Williams also planned a two-volume history of Reconstruction in the former Confederacy, but he never went beyond incorporating some of the materials he had collected for the project into his lectures in the United States and Europe. In his writings and lectures, Williams expressed an optimism based on faith in a divine power that preordained events and enlisted adherents to assist in evangelizing the rest of the world’s peoples.

Williams had begun to lecture extensively early in the 1880s, and by the end of 1883 had returned to Boston, where he practiced law. He later resided in Worcester and continued his research at the American Antiquarian Society. In March 1885 lame-duck president Chester Arthur appointed Williams minister to Haiti. He was confirmed by the U.S. Senate and sworn in during the final hours of the outgoing Republican administration, but before Williams could assume the post, Democrat Grover Cleveland appointed someone else to it.

Ever restless and aggressively ambitious, Williams turned his sights toward Africa, already an occasional subject of his writing and public speaking. He attended an antislavery conference in Brussels in 1889 as a reporter for S. S. McClure’s syndicate and there met Leopold II, king of the Belgians. In the following year, without the blessing of the king but with the patronage of Collis P. Huntington, an American railroad magnate who had invested in several African projects, he visited the Congo. After an extensive tour of the country, which took him from Boma on the Atlantic coast to the headwaters of the Congo River at Stanley Falls, he had a clear impression of what the country was like and why. Having witnessed the brutal conduct and inhumane policies of the Belgians, Williams decided to speak out. He published for circulation throughout Europe and the United States An Open Letter to His Serene Majesty, Leopold II, King of the Belgians, thus becoming a pioneering opponent of Leopold’s policies and anticipating later criticisms of Europe’s colonial ventures in Africa. Among the barrage of charges against the king was that his title to the Congo was, at best, “badly clouded” because his treaties with the local chiefs were “tainted by frauds of the grossest character.” He held the king responsible for “deceit, fraud, robberies, arson, murder, slave-raiding, and general policy of cruelty” in the Congo. “All the crimes perpetrated in the Congo have been done in your name,” he concluded, “and you must answer at the bar of Public Sentiment for the misgovernment of a people, whose lives and fortunes were entrusted to you by the august Conference of Berlin, 1884–1885.” While the attack inspired denunciations of Williams in Belgium, it was little noted in the United States, though Williams had already written a report on the Congo for President Benjamin Harrison at the latter’s request. A closer scrutiny of conditions in the Congo would come only after such “credible” persons as Roger Casement of the British foreign office and Mark Twain made charges against Leopold that echoed those of Williams.

Following his exploration of the Congo and southern Africa, Williams fell ill in Cairo, Egypt, after giving a lecture before the local geographical society (he had not been in robust health since being wounded in the army). Separated but not divorced from his wife, he subsequently went to London with his English “fiancée,” Alice Fryer, intending to write a lengthy work on colonialism in Africa. There, tuberculosis and pleurisy overtook him, and he died in Blackpool. In the United States, his death was noted in the national media as well as in the black press.

To the end, George Washington Williams remained a difficult person to understand fully. To many on both sides of the racial divide he possessed a curious combination of rare genius, remarkable resourcefulness, and an incomparable talent for self-aggrandizement. Although Williams was justifiably chided during his lifetime for making inflated claims about his background, W. E. B. Du Bois did not hesitate to pronounce him, long after his death, “the greatest historian of the race.”

There are numerous Williams letters in collections of other people’s correspondence, including the George F. Hoar Papers at the Massachusetts Historical Society in Boston and the Collis P. Huntington Papers at the George Arents Library at Syracuse University.

Franklin, John Hope. George Washington Williams: A Biography (1985).

—JOHN HOPE FRANKLIN

WILLIAMS, JOHN ALFRED

WILLIAMS, JOHN ALFRED(5 Dec. 1925–), novelist, journalist, and teacher, was born in Jackson, Mississippi, to John Henry Williams and Ola Mae, whose maiden name is unknown. Soon after his birth, the family returned to Syracuse, New York, where his father was a laborer and his mother a domestic. Williams attended Central High School in Syracuse, leaving in 1943 to enter the U.S. Navy. After service in the Pacific theater during World War II, he returned to Syracuse, completed high school, and, in 1947, married Carolyn Clopton; the couple had two sons, Gregory and Dennis. Williams entered Syracuse University and graduated in 1950 with a bachelor’s degree in Journalism and English. He did graduate work in 1951–1952 before financial circumstances forced him to withdraw; he and Clopton also divorced in 1952.

Williams held several paid writing positions in the 1950s: he was a public relations writer in Syracuse, publicity director for Comet Press Books, editor of Negro Market Newsletter, a publisher’s assistant, and European correspondent for both Ebony and Jet magazines. He incorporated these experiences into his first novel, The Angry Ones (1960), which draws mainly on his employment at Comet Press.

Williams’s second novel, Night Song (1962), marks the start of his deep exploration of African American music, especially jazz. An account of the life of Richie “Eagle” Stokes, a fictitious saxophonist who closely resembles CHARLIE PARKER, the novel describes the opportunities and limitations that an artistically talented black man must confront in his attempt to forge meaningful art in racist America. On the strength of it, Williams was informed that he would be selected to receive the Prix de Rome from the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

After receiving the informal letter of congratulations that promised him the prize, the author had an interview with the director of the academy, supposedly a mere formality. Instead, after the interview, the director informed Williams that the award had been rescinded. (Williams fictionalized the events in The Man Who Cried I Am [1967] and recounted them in “We Regret to Inform You That,” an essay reprinted in his collection Flashbacks [1973].) The director offered no explanation, though Williams speculated that his impending marriage to Lorrain Isaac, a white Jewish woman, was the cause. At this writing, Williams remains the only candidate to ever have had the prize retracted. Williams later married Isaac in 1965, and the couple had a son, Adam.