X, LOUIS.

X, LOUIS. X, LOUIS.

X, LOUIS.See Farrakhan, Louis Abdul.

X, MALCOLM.

X, MALCOLM.See Malcolm X.

YORK

YORK(c. 1772-before 1832), explorer, slave, and the first African American to cross the North American continent from coast to coast north of Mexico, is believed to have been born in Caroline County, Virginia, the son of an enslaved African American also named York (later called Old York), owned by John Clark, a member of the Virginia gentry and father of the famous George Rogers Clark and William Clark. York’s mother is unidentified; it is likely that she, too, was a Clark family slave. A slave named Rose is sometimes listed as York’s mother, but sources best identify her as his stepmother. York is believed to have been assigned while a child to William Clark as his servant and companion. Since such relationships were generally between children of about the same age, with the slave sometimes a few years younger, York may have been about two or three years Clark’s junior. As the boys grew older, their roles would have become more sharply defined as master and slave. York would have learned everything necessary to serve properly as the body servant of a young Virginia gentleman. He was essentially following in his father’s footsteps, since Old York was John Clark’s body servant and a trusted slave. York would not have received any formal schooling and was most likely illiterate.

In March 1785 the John Clark family settled in Jefferson County, Kentucky, near Louisville. Once in Kentucky, York would have learned many of the same frontier skills as William Clark did. York probably accompanied Clark during the latter’s service as a lieutenant in the U.S. Army from 1792 to 1796. A letter of 1 June 1795 by Clark mentioning that his “boy” had arrived at Fort Greenville, Ohio, might be the earliest known reference to York (Holmberg, 273, 274n). The first certain record of York is his listing in the July 1799 will of John Clark. By that will York officially became the property of William Clark.

In 1803 Clark accepted Meriwether Lewis’s invitation to join him as coleader of the famous Lewis and Clark expedition (1803–1806) to the Pacific Ocean, and he took his slave with him. Thus, York was one of the earliest members of the Corps of Discovery and part of the important foundation formed in 1803 at the Falls of the Ohio, at Louisville. York was not an official member of the corps; he was carried on the rolls as Clark’s servant and received no pay or land grant for his service. Nonetheless, he was an important member of the expedition, and Clark would have had little hesitation in taking him. Clark had traveled widely as a soldier and a civilian, and York almost certainly traveled with him on some, if not most, of his trips. Thus, York was an experienced traveler by land and water and possessed many of the same abilities the captains required of expedition recruits.

It was a bonus to have York present as a servant to make camp life easier for the captains. And York would have had a definite presence. Expedition-related documents provide a basic physical description of him as a large man (apparently both in height and weight), very strong, agile for his size, and very black. A personality also emerges. York was loyal, caring, and determined, and he had a sense of humor. The expedition journals also give us a basic understanding of York’s experience on the journey. The dangers and hardships of the expedition had a leveling effect on the men of the corps. While York never would have completely escaped his slave status, his participation in the daily experiences and work of the corps resulted in his acceptance as one of the group at a level he never would have enjoyed before the expedition. Additional evidence of this is York’s inclusion in the November 1805 vote of expedition members regarding the location of their winter quarters. The very fact that York’s opinion was sought and recorded with the others’ votes reflects his acceptance and status.

An additional benefit for the corps, and a revelation to York, was realized when the explorers encountered American Indians who had never before seen a black man. Those native people almost always greeted York with awe and respect. In their cultures his uniqueness gave him great spiritual power. They also admired his enormous size, strength, and agility. The Arikara Indians named him “Big Medicine.” York was consequently used to help advance the expedition. For his part, this was a new and enlightening experience. In only a couple of years he had gone from a societal and racial inferior to a position of relative equality in a primarily white group and even to being viewed by many Indians as superior to his white companions.

On 23 September 1806 the explorers arrived in St. Louis on their return from the Pacific Ocean. The men were discharged and other business taken care of before traveling eastward. On 5 November 1806 Lewis, Clark, York, and others arrived in Louisville, where York was reunited with his wife. (Only one other returning member of the expedition was married.) The names of York’s wife and her owner are unknown. When York was married is not known either, though it was before October 1803, when the nucleus of the corps pushed off from the Louisville area. Nor is it known whether they had any children. There are oral traditions among some of the Indian tribes the corps visited that York left behind descendants, and Clark also made a reference in 1832 to stories he had heard that York left descendants among the Indians of the Missouri River.

Over the next year and a half Clark traveled between Louisville, St. Louis, and Virginia. York almost certainly went with him as his servant. In June 1808 Clark and his bride, Julia Hancock, moved to St. Louis to establish their permanent residence, bringing with them a number of their slaves, including York. The situation now changed for York. The years of periodic travel had meant separation from his wife, but York also knew he would be returning. Now his visits to her would be periodic and probably short. York went so far as to ask to be hired out or sold to someone in Louisville. Clark refused to grant this request and told him to forget about his wife. York persisted until Clark relented and allowed him to go for a visit, though he was angry enough to threaten to sell York or hire him out to a severe master if he tried to “run off” or failed to “perform his duty as a slave” (Holmberg, 160). A month later Clark noted that because of York’s “notion about freedom and his immense services,” he doubted York would ever be of service to him again (Holmberg, 183).

By spring 1809 York had returned to St. Louis, but only briefly. His attitude was no better, in Clark’s opinion, and punishment failed to improve it. Clark therefore determined to keep York in Louisville. But rather than sell him, Clark hired him out for at least the next six years. In November 1815 York was still a slave, working as the wagon driver in a freight-hauling business that Clark and a nephew started in Louisville. From then until 1832 York disappears from known records.

In 1832 Clark reported to Washington Irving that he had freed York and set him up in a freight-hauling business between Nashville, Tennessee, and Richmond (Kentucky, it is believed), that York had proved a poor businessman, that he had regretted getting his freedom, and that while trying to return to Clark in St. Louis, he had died of cholera in Tennessee. A happier, but unsubstantiated, ending has York returning to the West, where he lived in the Rocky Mountains as a chief among the Crow Indians, but despite some possible slaveholder rationalization, there is no reason to doubt the main points of Clark’s statement. The possibility that York traveled deeper into slave territory upon being freed is indeed unusual. It may be that York’s wife’s owner had moved to Nashville and that York followed her there after being manumitted.

An assessment of his participation in the Lewis and Clark expedition shows that York made definite contributions to its success. His experience undoubtedly altered his perspective on race and his place in society. Even though doing so alienated him from Clark and brought him further hardship and unhappiness, he spoke up for the rights and freedom he believed he had earned by his years of loyal service and his role in the expedition. It is ironic that the very thing that made him a slave and inferior in white society—the color of his skin—marked him as someone to be respected and admired among many of the Indian tribes encountered on one of the most famous journeys in U.S. history.

Betts, Robert B. In Search of York The Slave Who Went to the Pacific with Lewis and Clark, revised with a new epilogue by James J. Holmberg (2000).

Holmberg, James J., ed. Dear Brother: Letters of William Clark to Jonathan Clark (2002).

—JAMES J. HOLMBERG

YOUNG, ANDREW JACKSON, JR.

YOUNG, ANDREW JACKSON, JR.(12 Mar. 1932–), civil rights leader, United Nations ambassador, U.S. congressman, and mayor, was born in New Orleans, Louisiana, the son of Andrew Jackson Young, a dentist, and Daisy Fuller, a teacher. Young received a BS degree in Biology from Howard University in 1951 and a Bachelor of Divinity degree from Hartford Theological Seminary in Connecticut in 1955. In the same year he was ordained as a minister in the United Church of Christ. As a pastor he was sent to such places as Marion, Alabama, and Thomasville and Beachton, Georgia. During this time the civil rights movement was reaching its height under the leadership of MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. and others who followed the nonviolent resistance tactics of Mohandas Gandhi, the pacifist who had led Indian opposition to British colonial rule. By the time of the Montgomery, Alabama, bus boycott in 1955, Young and several of his parishioners had decided to join the movement. Young himself was actively engaged in voter registration drives.

In 1957 Young returned north to serve as associate director of the Department of Youth Work of the National Council of Churches in New York City. The United Church of Christ then solicited him in 1961 to lead a voter registration drive, focusing on southern blacks who were unaware of their voting rights. Around this time he became involved with King’s organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). By 1962 Young had become an administrative assistant to King, and in 1964 he was appointed SCLC’s executive officer. Although Young originally opposed King’s decision to support a strike by sanitation workers in Memphis, Tennessee, he finally joined and was there at the Lorraine Motel when King was assassinated on 4 April 1968.

King’s death signaled the end of one phase of the civil rights movement, but Young soon became active in the movement’s new focus on electoral politics. In 1970 Young entered the race for the Democratic nomination in Georgia’s Fifth Congressional District, whose boundaries encompassed much of the southern part of metropolitan Atlanta and contained 40 percent of the area’s African American population. Young’s opponents were two white candidates and an African American, Lonnie King, an NAACP activist and a former leader of the Atlanta sit-in movement. Although Young was victorious in the Democratic primary, he lost the general election to the Republican challenger, Fletcher Thompson. Inclement weather on election day and a failure to energize some black voters contributed to Young’s defeat.

Andrew Young during his tenure as Democratic congressman from Georgia, around 1972. Library of Congress

Following that loss, Young became the chairman of Atlanta’s Community Relations Commission (CRC) and fought for a better public transit system and against Atlanta’s growing drug trafficking and drug use problems. These actions increased his visibility and popularity across the fifth district, and in 1972 he again sought a seat in the House. After running a more aggressive campaign, particularly in African American communities, Young received approximately 52 percent of the vote in the general election. By accomplishing this feat, even in a district that was 62 percent white, Young became the first black congressman elected from Georgia since the end of Reconstruction. Indeed, that year Young and BARBARA JORDAN were the first African Americans elected to Congress from any southern state since North Carolina’s GEORGE WHITE in 1898. Young was reelected, by comfortable margins, in 1974 and 1976. During the presidential campaign of 1976, he became a strong supporter of the Democratic candidate, Jimmy Carter, a former Georgia governor.

In 1977, after Carter was elected president, he appointed Young as U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations (UN). As ambassador, Young championed African issues and visited the African continent several times. He also vehemently attacked the South African system of racial apartheid. But, after only two-and-one-half years in office, Young resigned his ambassadorial post in August 1979. This came shortly after a meeting with Zehdi Lahib Terzi, the UN observer for the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO). The PLO, at this time, was considered an international terrorist group by the United States government. By meeting with a PLO representative, Young violated state department rules prohibiting official contact with the Palestinian organization. Following his resignation, Young told the Atlanta Journal that efforts for peace in the Middle East were at a crucial and perhaps pivotal juncture, and that he had met with the PLO because a chance for peace had to be pursued.

After resigning as UN ambassador, Young returned to Atlanta and founded a consulting firm called Law International, Inc. (later GoodWorks International). The company promoted trade, especially with African nations. Seemingly satisfied with his new and financially lucrative career in business, Young, in 1981, became a reluctant candidate for mayor of Atlanta, after being urged to do so by CORETTA SCOTT KING, outgoing mayor Maynard Jackson, and others. During his campaign Young made a special effort to reach out to white businessmen, many of whom had been alienated by the affirmative action policies of the administration of Jackson, Atlanta’s first black mayor. Young received 55 percent of the total vote in the election of 1981 and was reelected by a larger margin in 1985. His administrations were marked by renewed economic growth, including a revitalization of the Underground Atlanta tourist attraction, increased convention trade in the city, and a decrease in overall crime. It also was credited with a major triumph when Atlanta won the right to host the Democratic National Convention in 1988. By 1984 white business leaders were already telling publications like Ebony magazine that the city’s reputation had improved in the boardrooms of corporate America. The Young administration, however, drew broad criticisms for its historic preservation and neighborhood revitalization policies. The city’s Urban Design Commission and neighborhood activists consistently protested proposals to demolish historic buildings and housing in favor of new commercial buildings and highways—and during and after the 1988 Democratic National Convention, the administration was chastised for its rough handling of antiabortion demonstrators.

Young’s mayoral term ended in 1989, but his political aspirations remained strong. The next year he made an unsuccessful run for governor of Georgia against the state’s popular lieutenant governor, Zell Miller. Remaining active in business and civic affairs, Young then led a bid by the city of Atlanta to host the 1996 summer Olympic Games. Atlanta’s success in winning the bid to host the Centennial Games was largely attributed to Young’s popularity and influence among African and other Third World members of the International Olympic Committee (IOC). During the pre-Olympic and Olympic period in Atlanta (a span of more than four years), Young served as cochairman of the Atlanta Organizing Committee.

After the Olympics left Atlanta, Young returned full time to his international consulting firm and continued to serve on several corporate boards, including Delta Airlines, as well as the boards of several academic and humanitarian institutions. In 1999 he returned, in a sense, to his career origins when he was elected president of the National Council of Churches.

Young’s wife for forty years, Jean (a civil rights and civic activist), died in September 1994. He remarried shortly thereafter. He had fathered three children with Jean.

Unlike many of his contemporaries in the southern civil rights movement, Andrew Young’s most enduring contributions came after the great legal and political battles of the 1960s had been won. Serving as a congressman, a United Nations Ambassador, and a mayor of a large American city, he affected international, national, and local policies for more than twenty-five years. In each of his roles, but particularly as UN Ambassador, he was a principal liaison between the United States and the Third World.

Young, Andrew. An Easy Burden: The Civil Rights Movement and the Transformation of America (1996).

_______ A Way Out of No Way: The Spiritual Memoirs of Andrew Young (1994).

Gardner, Carl. Andrew Young, A Biography (1978).

Garrow, David J. Bearing the Cross: Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, 1955–1968 (1986).

Hornsby, Alton, Jr. A Short History of Black Atlanta (2003).

—ALTON HORNSBY JR.

YOUNG, COLEMAN

YOUNG, COLEMAN(24 May 1918–29 Nov. 1997), mayor, was born in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, the son of William Coleman Young, a barber and a tailor, and Ida Reese Jones Young. After his family moved to Detroit in 1923, Young grew up in the Black Bottom section of town, where his father ran a dry-cleaning and tailoring operation and also worked as a night watchman at the post office. Although Young enjoyed his early years in the then-ethnically diverse neighborhood, his family did not altogether escape discrimination. A gifted student, he was rejected by a Catholic high school because of his race, and after graduating from public Eastern High, he lost out on college financial aid for the same reason. Young became an electrical apprentice at Ford Motor Company, only to see a white man with lower test scores get the job. He then worked on Ford’s assembly line but was fired for fighting a thug from Harry Bennett’s Service Department who had identified Young as a union member.

After his dismissal from Ford, Young went to work for the National Negro Congress, a civil rights organization that focused on labor issues. While with the NNC, he worked at the post office and continued the fight to unionize Ford. When Henry Ford accepted a union contract, Young turned his attention to other issues such as open housing. Fired from his job in the post office for union activity, he was drafted into the army in February 1942. Young initially served in the infantry with the Ninety-second Buffalo Division before transferring to the U.S. Army Air Forces, where he underwent pilot training with the famed Tuskegee airmen. Washed out of the pilot program—an action Young blamed on FBI interference based on his years of unionizing and associating with so-called radicals—he spent the rest of the war fighting for equal accommodations for African American servicemen on a number of military bases.

Discharged from the air forces as a second lieutenant in December 1945, Young returned to Detroit, regained his position at the post office, and resumed his union organizing activities. In January 1947 he married Marion McClellan; the couple had no children before divorcing in 1954. Shortly thereafter he married Nadine Drake; that childless marriage also ended in divorce a few years later. As a member of the United Public Workers, he soon ran afoul of Walter Reuther, whose conservative brand of anticommunist leadership within the United Auto Workers extended to the Congress of Industrial Organizations. Although Young had been elected to an executive post with the Wayne County, Michigan, chapter of the CIO, he lost his position in 1948 on account of Reuther’s political machinations. Following a disastrous run for the state senate as a candidate of Henry Wallace’s Progressive Party that same year, Young drifted through a series of jobs before becoming the executive secretary of the newly formed National Negro Labor Council, which achieved some successes nationwide in increasing the range and number of job opportunities for African Americans. Targeted by the federal government as a subversive group, however, the organization folded under pressure in the spring of 1956. After a few more years of drifting between jobs, Young lost a bid for Detroit’s Common Council in 1960. Encouraged by the election results, he successfully gained a seat at Michigan’s Constitutional Convention. Following the convention Young spent several successful years as an insurance salesman for the Municipal Credit Union League before reentering politics for good in 1964, when he gained election to the Michigan State Senate.

Young remained in the senate until 1973, where he supported open housing and school busing legislation and eventually became Democratic floor leader. In 1973 he ran for mayor of Detroit and, with substantial union support, narrowly won a racially charged contest against former police commissioner John F. Nichols. After the election Young pledged to work together with business and labor to help turn around the badly troubled city, which was then reeling from high unemployment, rampant crime, white flight, the effects of the gasoline embargo, and the loss of its industrial base. Young presided over the 1977 opening of Renaissance Center, a downtown office-retail complex designed to revitalize the city’s riverfront, and was also instrumental in building new manufacturing plants for Chrysler and General Motors. Faced with the city’s possible bankruptcy, he persuaded voters to approve an income tax increase and gained wage and benefit concessions from municipal workers. Having run on a campaign of reforming the Detroit police department (long viewed as a source of oppression among African American residents), he increased the number of blacks and minorities on the force and also disbanded STRESS (Stop the Robberies, Enjoy Safe Streets), a special police decoy unit that was the focus of many complaints of brutality.

Reelected four times, Young enjoyed a particularly good relationship with President Jimmy Carter. Among the first to endorse Carter’s presidential campaign in 1976, Young served as vice chairman of the Democratic National Committee between 1977 and 1981 and from 1981 until 1983 headed the United States Conference of Mayors. He fared less well under Carter’s Republican successors, however, and also had to deal with long-running feuds with the local press as well as nearby suburban governments. Despite his long-held emphasis on racial cooperation, the blunt-spoken Young—who for years had a sign on his desk that read “Head Motherf**ker in Charge”—never gained the trust of many white voters, who deplored his confrontational style and his frequent overseas vacations. In addition to being the subject of federal criminal investigations, none of which resulted in any charges, Young was the target of a paternity suit by former city employee Annivory Calvert, with whom he had a son.

In declining health, Young chose not to run for reelection in 1993. He died in a Detroit hospital. Despite having to face a host of problems with resources that were limited at best, Young proved himself game in his efforts to preserve and revitalize one of America’s major metropolitan centers.

Young’s papers are divided between the Walter Reuther Library at Wayne State University and the African American Museum in Detroit.

Young, Coleman, with Lonnie Wheeler. Hard Stuff: The Autobiography of Coleman Young (1994).

Rich, Wilbur C. Coleman Young and Detroit Politics: From Social Activist to Power Broker (1989).

Obituaries: Detroit Free Press, 5 Dec. 1997; New York Times, 30 Nov. 1997.

—EDWARD L. LACH JR.

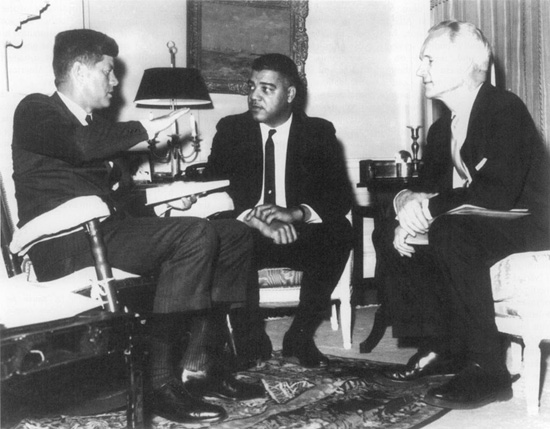

Whitney Moore Young, Jr. (center), executive director of the National Urban League, meeting with President John F. Kennedy and Henry Steeger at the White House in 1962. Library of Congress

YOUNG, WHITNEY MOORE, JR.

YOUNG, WHITNEY MOORE, JR.(31 July 1921–11 Mar. 1971), social worker and civil rights activist, was born in Lincoln Ridge, Kentucky, the son of Whitney Moore Young Sr., president of Lincoln Institute, a private African American college, and Laura Ray, a schoolteacher. Raised within the community of the private academy and its biracial faculty, Whitney Young Jr. and his two sisters were sheltered from harsh confrontations with racial discrimination in their early lives, but they attended segregated public elementary schools for African American children and completed high school at Lincoln Institute. In 1937 Young, planning to become a doctor, entered Kentucky State Industrial College at Frankfort, where he received a BS in 1941. After graduation he became an assistant principal and athletic coach at Julius Rosenwald High School in Madison, Kentucky.

After joining the U.S. Army in 1942, Young studied engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). In 1944 he married Margaret Buckner, a teacher whom he had met while they were both students at Kentucky State; they had two children. Sent to Europe later in 1944, Young rose from private to first sergeant in the all-black 369th Anti-Aircraft Artillery Group. His experience in a segregated army on the eve of President Harry Truman’s desegregation order drew Young to the challenges of racial diplomacy. In 1946, after his discharge from the army, he entered graduate study in social work at the University of Minnesota. His field placement in graduate school was with the Minneapolis chapter of the National Urban League, which sought increased employment opportunities for African American workers. In 1948 Young completed his master’s degree in Social Work and became industrial relations secretary of the St. Paul, Minnesota, chapter of the Urban League. In 1950 he became the director of the Urban League chapter in Omaha, Nebraska. He increased both the Omaha chapter’s membership and its operating budget. He became skilled at working with the city’s business and political leaders to increase employment opportunities for African Americans. In Omaha he also taught in the University of Nebraska’s School of Social Work.

In 1954 Young became dean of the School of Social Work at Atlanta University. As an administrator, he doubled the school’s budget, raised faculty salaries, and insisted on professional development. In these early years after the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, Young played a significant advisory role within the leadership of Atlanta’s African American community. He was active in the Greater Atlanta Council on Human Relations and a member of the executive committee of the Atlanta branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). He also helped to organize Atlanta’s Committee for Cooperative Action, a group of business and professional people who sought to coordinate the social and political action of varied black interest groups and organized patrols in African American communities threatened by white violence. He took a leave of absence from his position at Atlanta University in the 1960–1961 academic year to be a visiting Rockefeller Foundation scholar at Harvard University.

In January 1961 the National Urban League announced Whitney Young’s appointment to succeed Lester B. Granger as its executive director. Beginning his new work in fall 1961, Young came to the leadership of the Urban League just after the first wave of sit-in demonstrations and freedom rides had drawn national attention to new forms of civil rights activism in the South. Among the major organizations identified with the civil rights movement, the Urban League was the most conservative and the least inclined to favor public demonstrations for social change. Young was resolved to move it into a firmer alliance with the other major civil rights organizations without threatening the confidence of the Urban League’s powerful inside contacts. In 1963 he led it into joining the March on Washington and the Council for United Civil Rights Leadership, a consortium initiated by Kennedy administration officials and white philanthropists to facilitate fundraising and joint planning.

In his ten years as executive director of the Urban League, Young increased the number of its local chapters from sixty to ninety-eight, its staff from 500 to 1,200, and its funding by corporations, foundations, and federal grants. After the assassination of President John Kennedy, Young developed even stronger ties with President Lyndon Johnson’s administration. Perhaps Young’s most important influence lay in his call for a “Domestic Marshall Plan,” outlined in his book To Be Equal (1964), which influenced President Johnson’s War on Poverty programs.

By the mid-1960s, however, the civil rights coalition had begun to fray. In June 1966 Young and ROY WILKINS of the NAACP refused to sign a manifesto drafted by other civil rights leaders or to join them when they continued the march of JAMES MEREDITH from Memphis, Tennessee, to Jackson, Mississippi. Young continued to shun the black power rhetoric popular with new leaders of the Congress of Racial Equality and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. Simultaneously, in consideration of the vital alliance with the Johnson administration, he was publicly critical of MARTIN LUTHER KING JR.’s condemnation of the U.S. pursuit of the war in Vietnam. At the administration’s request, he twice visited South Vietnam to review American forces and observe elections there. Before Young left office in 1969, Lyndon Johnson awarded him the Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian citation.

After Richard Nixon’s inauguration in 1969, however, Young modified his earlier positions, condemning the war in Vietnam and responding to the Black Power movement and urban violence by concentrating Urban League resources on young people in the urban black underclass. He continued to have significant influence, serving on the boards of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, MIT, and the Rockefeller Foundation and as president of the National Conference on Social Welfare (1967) and of the National Association of Social Workers (1969–1971). Subsequently, Young’s successors as executive director of the Urban League, Arthur Fletcher, VERNON JORDAN, and John Jacob, maintained his legacy of commitment to the goals of the civil rights movement by sustained engagement with centers of American economic and political power.

In March 1971, while Young was at a conference on relations between Africa and the United States in Lagos, Nigeria, he suffered either a brain hemorrhage or a heart attack and drowned while swimming in the Atlantic Ocean. Former Attorney General Ramsey Clark and others who were swimming with him pulled Young’s body from the water, but their efforts to revive him were to no avail.

The Whitney M. Young Jr. Papers are in the Rare Book and Manuscript Library of Columbia University; the National Urban League Papers are at the Library of Congress.

Moore, Jesse Thomas, Jr. A Search for Equality: The National Urban League, 1910–1961 (1981).

Parris, Guichard, and Lester Brooks. Blacks in the City: A History of the National Urban League (1971).

Weiss, Nancy J. Whitney M. Young Jr. and the Struggle for Civil Rights (1990).

Obituary: New York Times, 12 Mar. 1971.

—RALPH E. LUKER