Best of the Rhine • Bacharach • Oberwesel • St. Goar • Koblenz

The Rhine Valley is storybook Germany, a fairy-tale world of legends and “robber-baron” castles. Cruise the most turret-studded stretch of the romantic Rhine as you listen for the song of the treacherous Loreley. For hands-on thrills, climb through the Rhineland’s greatest castle, Rheinfels, above the town of St. Goar. Connoisseurs will also enjoy the fine interior of Marksburg Castle near Koblenz. Spend your nights in a castle-crowned village, either Bacharach or St. Goar.

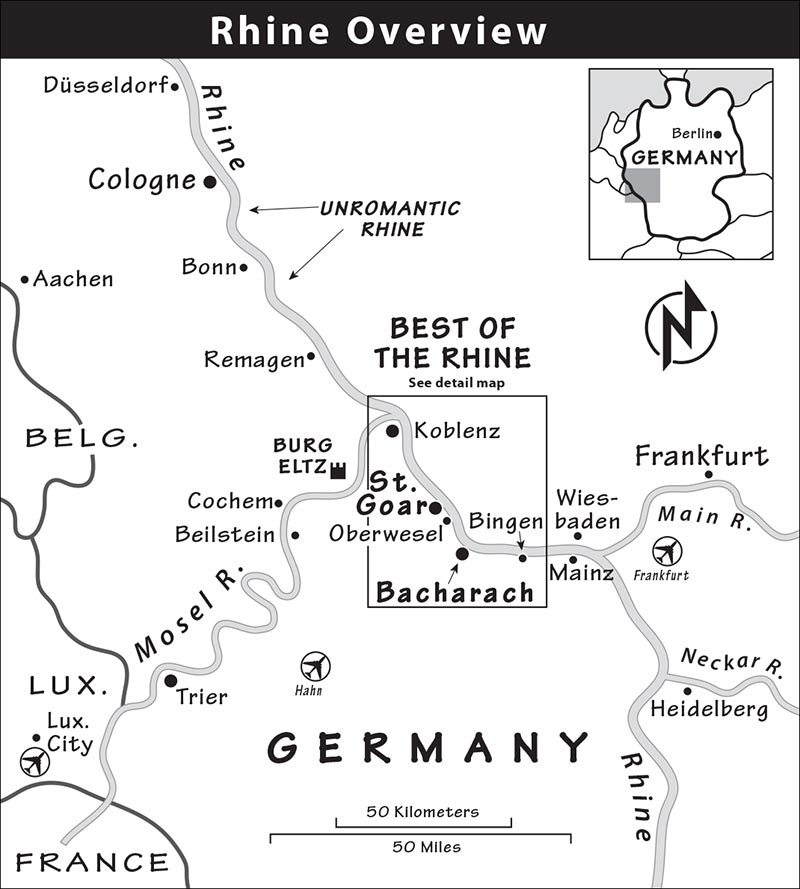

The Rhineland is magical, but doesn’t take much time to see. Both Bacharach and St. Goar are an easy one-hour train ride or drive from Frankfurt Airport, and make a good first or last stop for travelers flying in or out.

The blitziest tour of the area is an hour looking at the castles from your train window—use the narration in this chapter to give it meaning. The nonstop express runs every hour, connecting Koblenz and Mainz in 50 scenic minutes. (Super-express ICE trains between Cologne and Frankfurt bypass the Rhine entirely.) For a better look, cruise in, tour a castle or two, sleep in a medieval town, and take the train out.

Ideally, if you have two nights to spend here, sleep in Bacharach, cruise the best hour of the river (from Bacharach to St. Goar), and tour Rheinfels Castle. If rushed, focus on Rheinfels Castle and cruise less. With more time, add a visit to Koblenz or Oberwesel, or ride the riverside bike path. With another day, mosey through the neighboring Mosel Valley or day-trip to Cologne (both covered in different chapters).

There are countless castles in this region, so you’ll need to be selective in your castle-going. Aside from Rheinfels Castle, my favorites are Burg Eltz (see the next chapter; well preserved with medieval interior, set evocatively in a romantic forest the next valley over), Marksburg Castle (rebuilt medieval interior, with commanding Rhine perch), and Rheinstein Castle (a 19th-century duke’s hunting palace overlooking the Rhine). Marksburg is the easiest to reach by train.

If possible, visit the Rhine between April and October. The low season (winter and spring) is lower here than in some other parts of Germany. Many hotels and restaurants close from November to February or March. Only one riverboat runs, sights close or have short hours, and neither Bacharach nor St. Goar have much in the way of Christmas markets.

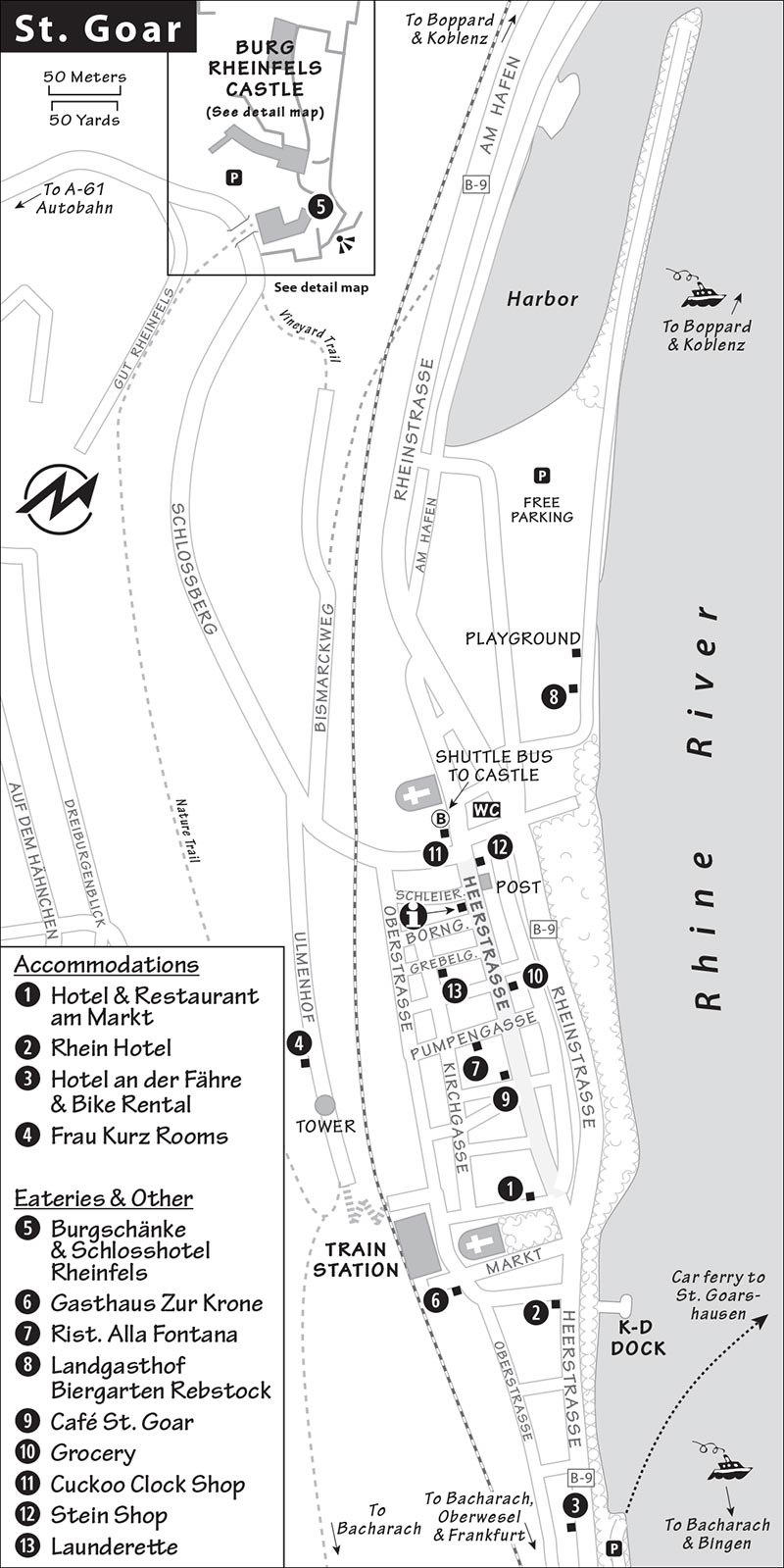

Bacharach and St. Goar, the best towns for an overnight stop, are 10 miles apart, connected by milk-run trains, riverboats, and a riverside bike path. Bacharach is a much more interesting town, but St. Goar has the famous Rheinfels Castle. In general, the Rhine is an easy place for cheap sleeps. B&Bs and Gasthäuser with inexpensive beds abound (and normally discount their prices for longer stays). Rhine-area hostels offer cheap beds to travelers of any age. Finding a room should be easy in high season (except for Sept-Oct wine-fest weekends). Note: Rhine Valley towns often have guesthouses and hotels with similar names—when reserving, double-check that you’re contacting the one in your planned destination.

Ever since Roman times, when this was the empire’s northern boundary, the Rhine has been one of the world’s busiest shipping rivers. Although the name “Rhine” derives from a Celtic word for “raging,” the river you see today has been tamed and put to work. You’ll see a steady flow of barges with 1,000- to 2,000-ton loads. Cars, buses, and trains rush along highways and tracks lining both banks.

Many of the castles were “robber-baron” castles, put there by petty rulers (there were 300 independent little countries in medieval Germany, a region about the size of Montana) to levy tolls on passing river traffic. A robber baron would put his castle on, or even in, the river. Then, often with the help of chains and a tower on the opposite bank, he’d stop each ship and get his toll. There were 10 customs stops in the 60-mile stretch between Mainz and Koblenz alone (no wonder merchants were early proponents of the creation of larger nation-states).

Some castles were built to control and protect settlements, and others were the residences of kings. As times changed, so did the lifestyles of the rich and feudal. Many castles were abandoned for more comfortable mansions in the towns.

Most Rhine castles date from the 11th, 12th, and 13th centuries. When the pope successfully asserted his power over the German emperor in 1076, local princes ran wild over the rule of their emperor. The castles saw military action in the 1300s and 1400s, as emperors began reasserting their control over Germany’s many silly kingdoms.

The castles were also involved in the Reformation wars, in which Europe’s Catholic and Protestant dynasties fought it out using a fragmented Germany as their battleground. The Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648) devastated Germany. The outcome: Each ruler got the freedom to decide if his people would be Catholic or Protestant, and one-third of Germans died. (Production of Gummi Bears ceased entirely.)

The French—who feared a strong Germany and felt the Rhine was the logical border between them and Germany—destroyed most of the castles as a preventive measure (Louis XIV in the 1680s, the Revolutionary army in the 1790s, and Napoleon in 1806). Many were rebuilt in the Neo-Gothic style in the Romantic Age—the late 1800s—and today are enjoyed as restaurants, hotels, hostels, and museums.

The Rhine flows north from Switzerland to Holland, but the scenic stretch from Mainz to Koblenz hoards all the touristic charm. Studded with the crenellated cream of Germany’s castles, it bustles with boats, trains, and highway traffic. Have fun exploring with a mix of big steamers, tiny ferries (Fähre), trains, and bikes.

By Boat: While some travelers do the whole Mainz-Koblenz trip by boat (5.5 hours downstream, 8.5 hours up), I’d just focus on the most scenic hour—from Bacharach to St. Goar. Sit on the boat’s top deck with your handy Rhine map-guide (or the kilometer-keyed tour in this chapter) and enjoy the parade of castles, towns, boats, and vineyards.

Two boat companies take travelers along this stretch of the Rhine. Boats run daily in both directions from early April through October, with only one boat running off-season.

Most travelers sail on the bigger, more expensive, and romantic Köln-Düsseldorfer (K-D) Line (recommended Bacharach-St. Goar trip: €14.80 one-way, €16.80 round-trip, bikes-€2.80/day; discounts: up to 30 percent if over 60, 20 percent with connecting train ticket, 20 percent with rail passes and does not count as a flexipass day; tel. 06741/1634 in St. Goar, tel. 06743/1322 in Bacharach, www.k-d.com). I’ve included an abridged K-D cruise schedule in this chapter. Complete, up-to-date schedules are posted at any Rhineland station, hotel, TI, and www.k-d.com. (Confirm times at your hotel the night before.) Purchase tickets at the dock up to five minutes before departure. The boat is never full. Romantics will enjoy the old-time paddle-wheeler Goethe, which sails each direction once a day (noted on schedule, confirm time locally).

The smaller Bingen-Rüdesheimer Line is slightly cheaper than the K-D, doesn’t offer any rail pass deals, and makes three trips in each direction daily from mid-March through October (Bacharach-St. Goar: €13.40 one-way, €15.40 round-trip, bikes-€2/day, buy tickets at ticket booth or on boat, ticket booth opens just before boat departs, 30 percent discount if over 60; departs Bacharach at 10:10, 12:00, and 15:15; departs St. Goar at 11:00, 14:00, and 16:15; tel. 06721/308-0810, www.bingen-ruedesheimer.de).

By Car: Drivers have these options: 1) skip the boat; 2) take a round-trip cruise from St. Goar or Bacharach; 3) draw pretzels and let the loser drive, prepare the picnic, and meet the boat; 4) rent a bike, bring it on the boat, and bike back; or 5) take the boat one-way and return to your car by train. When exploring by car, don’t hesitate to pop onto one of the many little ferries that shuttle across the bridgeless-around-here river.

By Ferry: As there are no bridges between Koblenz and Mainz, you’ll see car-and-passenger ferries (usually family-run for generations) about every three miles. Bingen-Rüdesheim, Lorch-Niederheimbach, Engelsburg-Kaub, and St. Goar-St. Goarshausen are some of the most useful routes (times vary; St. Goar-St. Goarshausen ferry departs each side every 20 minutes daily until 22:30, less frequently Sun; one-way fares: adult-€1.80, car and driver-€4.50, pay on boat; www.faehre-loreley.de). For a fun little jaunt, take a quick round-trip with some time to explore the other side.

By Bike: Biking is a great way to explore the valley. You can bike either side of the Rhine, but for a designated bike path, stay on the west side, where a 35-mile path runs between Koblenz and Bingen. The eight-mile stretch between St. Goar and Bacharach is smooth and scenic, but mostly along the highway. The bit from Bacharach to Bingen hugs the riverside and is car-free. Some hotels have bikes for guests; Hotel an der Fähre in St. Goar also rents to the public (reserve in advance).

Consider biking one-way and taking the bike back on the riverboat, or designing a circular trip using the fun and frequent shuttle ferries. A good target is Kaub (where a tiny boat shuttles sightseers to the better-from-a-distance castle on the island) or Rheinstein Castle.

By Train: Hourly milk-run trains hit every town along the Rhine (Bacharach-St. Goar in both directions about :50 after the hour, 10 minutes; Mainz-Bacharach, 40 minutes; Mainz-Koblenz, 1 hour). Express trains speed past the small towns, taking only 50 minutes nonstop between Mainz and Koblenz. Tiny stations are unstaffed—buy tickets at machines. Though generally user-friendly, some ticket machines claim to only take exact change; others may not accept US credit cards. When buying a ticket, be sure to select “English” and follow the instructions carefully. The ticket machine may give you the choice of validating your ticket for that day or a day in the near future—but only for some destinations (if you’re not given this option, your ticket will automatically be validated for the day of purchase).

The Rheinland-Pfalz-Ticket day pass covers travel on milk-run trains to anywhere in this chapter—plus the Mosel Valley chapter (and also Remagen, but not Frankfurt, Cologne, or Bonn). It can save heaps of money, particularly on longer day trips or for groups (1 person-€24, up to 4 additional people-€5/each, buy at station ticket machines—may need to select Rhineland-Palatinate, good after 9:00 Mon-Fri and all day Sat-Sun, valid on trains labeled RB, RE, and MRB). For a day trip between Bacharach and Burg Eltz (normally €35 round-trip), even one person saves with a Rheinland-Pfalz-Ticket, and a group of five adults saves €130—look for travel partners at breakfast.

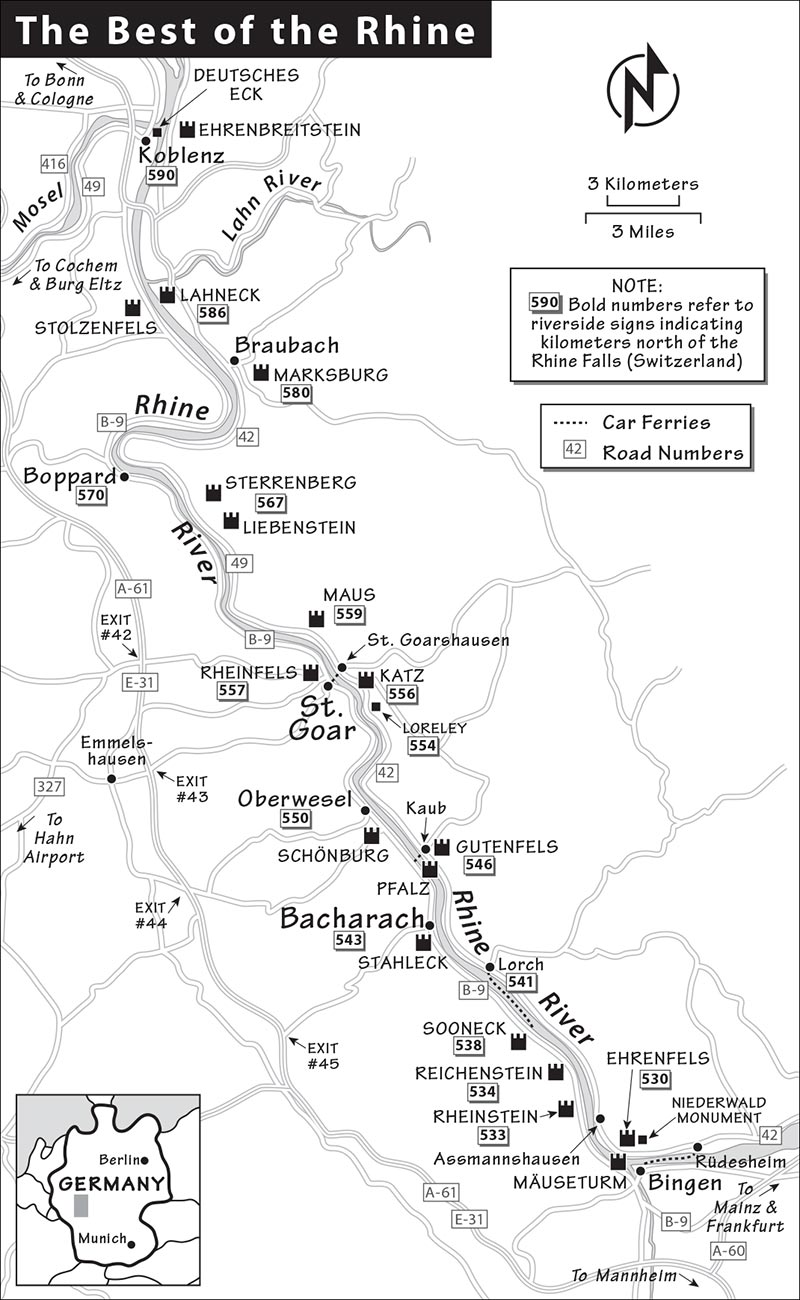

One of Europe’s great train thrills is zipping along the Rhine enjoying this self-guided blitz tour, worth ▲▲▲. Or, even better, do it while relaxing on the deck of a Rhine steamer, surrounded by the wonders of this romantic and historic gorge. This quick and easy tour (you can cut in anywhere) skips most of the syrupy myths filling normal Rhine guides. You can follow along on a train, boat, bike, or car. By train or boat, sit on the left (river) side going south from Koblenz. While nearly all the castles listed are viewed from this side, train travelers need to clear a path to the right window for the times I yell, “Cross over!”

You’ll notice large black-and-white kilometer markers along the riverbank. I erected these years ago to make this tour easier to follow. They tell the distance from the Rhine Falls, where the Rhine leaves Switzerland and becomes navigable. (Today, river-barge pilots also use these markers to navigate.) If you’re doing the tour by train and are stuck on the wrong side, keep an eye out for green-and-white signs that also show these numbers.

We’re tackling just 36 miles (58 km) of the 820-mile-long (1,320-km) Rhine. Your Best of the Rhine Tour starts at Koblenz and heads upstream to Bingen. If you’re going the other direction, it still works. Just hold the book upside-down.

Download my free Best of the Rhine audio tour—it works in either direction.

Download my free Best of the Rhine audio tour—it works in either direction.

Of the major sights and towns mentioned here, Marksburg and Rheinstein castles and the Loreley Visitors Center are described in more detail under “Sights Along the Rhine” (see next section); the others—Koblenz, St. Goar (and Rheinfels Castle), Obwerwesel, and Bacharach—are covered later in this chapter. For Burg Eltz, see the next chapter.

Km 590—Koblenz: This Rhine blitz starts with Romantic Rhine thrills, at Koblenz. Koblenz isn’t terribly attractive (it was hit hard in World War II), but its place at the historic Deutsches Eck (“German Corner”)—the tip of land where the Mosel River joins the Rhine—gives it a certain patriotic charm. A cable car links the Deutsches Eck with the yellow Ehrenbreitstein Fortress across the river.

Km 586—Lahneck Castle: Above the modern autobahn bridge over the Lahn River, this castle (Burg) was built in 1240 to defend local silver mines. The castle was ruined by the French in 1688 and rebuilt in the 1850s in Neo-Gothic style. Burg Lahneck faces another Romantic rebuild, the yellow Schloss Stolzenfels (€5, out of view above the train, Tue-Sun 10:00-18:00, closed Mon, Sat-Sun only and shorter hours off-season, closed Dec-Jan, a 10-minute climb from tiny parking lot, www.schloss-stolzenfels.de). Note that a Burg is a defensive fortress, while a Schloss is mainly a showy palace.

Km 580—Marksburg Castle: This castle stands bold and white—restored to look like most Rhine castles once did, with their slate stonework covered with stucco to look as if made from a richer stone. You’ll spot Marksburg with the three modern smokestacks behind it (these vent Europe’s biggest car-battery recycling plant just up the valley), just before the town of Spay. This is the best-looking of all the Rhine castles and the only surviving medieval castle on the Rhine. Because of its commanding position, it was never attacked in the Middle Ages (though it was captured by the US Army in March 1945). It’s now a museum with a medieval interior second only to the Mosel Valley’s Burg Eltz.

If you haven’t read the sidebar on river traffic (later in this chapter), now’s a good time.

Km 570—Boppard: Once a Roman town, Boppard has some impressive remains of fourth-century walls. Look for the Roman towers and the substantial chunk of Roman wall near the train station, just above the main square. You’ll notice that a church is a big part of each townscape. Many small towns have two towering churches. Four centuries ago, after enduring a horrific war, each prince or king decided which faith his subjects would follow (more often Protestant to the north and east, Catholic to the south and west). While church attendance in Germany is way down, the towns here, like Germany as a whole, are still divided between Catholic and Protestant.

If you visit Boppard, head to the fascinating Church of St. Severus below the main square. Find the carved Romanesque crazies at the doorway. Inside, to the right of the entrance, you’ll see Christian symbols from Roman times. Also notice the painted arches and vaults (originally, most Romanesque churches were painted this way). Down by the river, look for the high-water (Hochwasser) marks on the arches from various flood years. You’ll find these flood marks throughout the Rhine and Mosel valleys.

Km 567—Sterrenberg Castle and Liebenstein Castle: These neighboring castles, across from the town of Bad Salzig, are known as the “Hostile Brothers”. Notice how they’re isolated from each other by a low-slung wall. The wall was built to improve defenses from both castles, but this is the romantic Rhine so there has to be a legend: Take one wall between castles, add two greedy and jealous brothers and a fair maiden, and create your own legend. $$$ Burg Liebenstein is now a fun, friendly, and reasonably affordable family-run hotel (9 rooms, giant king-and-the-family room, easy parking, tel. 06773/251, www.castle-liebenstein.com, info@burg-liebenstein.de, Nickenig family).

Km 560: While you can see nothing from here, a 19th-century lead mine functioned on both sides of the river, with a shaft actually tunneling completely under the Rhine.

Km 559—Maus Castle: The Maus (mouse) got its name because the next castle was owned by the Katzenelnbogen family. (Katz means “cat.”) In the 1300s, it was considered a state-of-the-art fortification...until 1806, when Napoleon Bonaparte had it blown apart with then-state-of-the-art explosives. It was rebuilt true to its original plans in about 1900. Today, Burg Maus is open for concerts, weddings, and guided tours in German (20-minute walk up, weekends only, reservations required, tel. 06771/2303, www.burg-maus.de).

Km 557—St. Goar and Rheinfels Castle: Cross to the other side of the train. The pleasant town of St. Goar was named for a sixth-century hometown monk. It originated in Celtic times (i.e., really old) as a place where sailors would stop, catch their breath, send home a postcard, and give thanks after surviving the seductive and treacherous Loreley crossing. St. Goar is worth a stop to explore its mighty Rheinfels Castle.

Km 556—Katz Castle: Burg Katz (Katzenelnbogen) faces St. Goar from across the river. Together, Burg Katz (built in 1371) and Rheinfels Castle had a clear view up and down the river, effectively controlling traffic (there was absolutely no duty-free shopping on the medieval Rhine). Katz got Napoleoned in 1806 and rebuilt in about 1900.

In 1995, a wealthy and eccentric Japanese man bought it for about $4 million. His vision: to make the castle—so close to the Loreley that Japanese tourists are wild about—an exotic escape for his countrymen. But the town wouldn’t allow his planned renovation of the historic (and therefore protected) building. Stymied, the frustrated investor abandoned his plans. Today, Burg Katz sits empty...the Japanese ghost castle.

Below the castle, notice the derelict grape terraces—worked since the eighth century, but abandoned in the last generation. Yet Rhine wine remains in demand. The local slate absorbs the heat of the sun and stays warm all night, resulting in sweeter grapes. Wine from the steep side of the Rhine gorge—where grapes are harder to grow and harvest—is tastier and more expensive.

About Km 555: A statue of the Loreley, the beautiful-but-deadly nymph, combs her hair at the end of a long spit—built to give barges protection from vicious ice floes that until recent years raged down the river in the winter. The actual Loreley, a landmark cliff, is just ahead.

Km 554—The Loreley: Steep a big slate rock in centuries of legend and it becomes a tourist attraction—the ultimate Rhinestone. The Loreley (name painted near shoreline), rising 450 feet over the narrowest and deepest point of the Rhine, has long been important. It was a holy site in pre-Roman days. The fine echoes here—thought to be ghostly voices—fertilized legend-tellers’ imaginations.

Because of the reefs just upstream (at km 552), many ships never made it to St. Goar. Sailors (after days on the river) blamed their misfortune on a wunderbare Fräulein, whose long, blond hair almost covered her body. Heinrich Heine’s Song of Loreley (the CliffsNotes version is on local postcards, and you’ll hear it on K-D boats) tells the story of a count sending his men to kill or capture this siren after she distracted his horny son, who forgot to watch where he was sailing and drowned. When the soldiers cornered the nymph in her cave, she called her father (Father Rhine) for help. Huge waves, the likes of which you’ll never see today, rose from the river and carried Loreley to safety. And she has never been seen since.

But alas, when the moon shines brightly and the tour buses are parked, a soft, playful Rhine whine can still be heard from the Loreley. As you pass, listen carefully (“Sailors...sailors...over my bounding mane”). Today a visitors center keeps the story alive; if you visit you can hike to the top of the cliff.

Km 552—The Seven Maidens: Killer reefs, marked by red-and-green buoys, are called the “Seven Maidens.” OK, one more goofy legend: The prince of Schönburg Castle (über Oberwesel—described next) had seven spoiled daughters who always dumped men because of their shortcomings. Fed up, he invited seven of his knights to the castle and demanded that his daughters each choose one to marry. But they complained that each man had too big a nose, was too fat, too stupid, and so on. The rude and teasing girls escaped into a riverboat. Just downstream, God turned them into the seven rocks that form this reef. While this story probably isn’t entirely true, there was a lesson in it for medieval children: Don’t be hard-hearted.

Km 550—Oberwesel: Cross to the other side of the train. The town of Oberwesel, topped by the commanding Schönburg Castle (now a hotel), boasts some of the best medieval wall and tower remains on the Rhine.

Notice how many of the train tunnels along here have entrances designed like medieval turrets—they were actually built in the Romantic 19th century. OK, back to the riverside.

Km 547—Gutenfels Castle and Pfalz Castle, the Classic Rhine View: Burg Gutenfels (now a privately owned hotel) and the shipshape Pfalz Castle (built in the river in the 1300s) worked very effectively to tax medieval river traffic. The town of Kaub grew rich as Pfalz raised its chains when boats came, and lowered them only when the merchants had paid their duty. Those who didn’t pay spent time touring its prison, on a raft at the bottom of its well. In 1504, a pope called for the destruction of Pfalz, but the locals withstood a six-week siege, and the castle still stands. Notice the overhanging outhouse (tiny white room between two wooden ones). Pfalz (also known as Pfalzgrafenstein) is tourable but bare and dull (€2.50 ferry from Kaub, €3 entry, Tue-Sun 10:00-18:00, closed Mon; shorter hours in March; Nov and Jan-Feb Sat-Sun only, closed Dec; last entry one hour before closing, mobile 0172-262-2800, www.burg-pfalzgrafenstein.de).

In Kaub, on the riverfront directly below the castles, a green statue (near the waving flags) honors the German general Gebhard von Blücher. He was Napoleon’s nemesis. In 1813, as Napoleon fought his way back to Paris after his disastrous Russian campaign, he stopped at Mainz—hoping to fend off the Germans and Russians pursuing him by controlling that strategic bridge. Blücher tricked Napoleon. By building the first major pontoon bridge of its kind here at the Pfalz Castle, he crossed the Rhine and outflanked the French. Two years later, Blücher and Wellington teamed up to defeat Napoleon once and for all at Waterloo.

Immediately opposite Kaub (where the ferry lands, marked by blue roadside flags) is a gaping hole in the mountainside. This marks the last working slate mine on the Rhine.

Km 544—“The Raft Busters”: Just before Bacharach, at the top of the island, buoys mark a gang of rocks notorious for busting up rafts. The Black Forest, upstream from here, was once poor, and wood was its best export. Black Foresters would ride log booms down the Rhine to the Ruhr (where their timber fortified coal-mine shafts) or to Holland (where logs were sold to shipbuilders). If they could navigate the sweeping bend just before Bacharach and then survive these “raft busters,” they’d come home reckless and horny—the German folkloric equivalent of American cowboys after payday.

Km 543—Bacharach and Stahleck Castle: Cross to the other side of the train. The town of Bacharach is a great stop. Some of the Rhine’s best wine is from this town, whose name likely derives from “altar to Bacchus” (the Roman god of wine). Local vintners brag that the medieval Pope Pius II ordered Bacharach wine by the cartload. Perched above the town, the 13th-century Burg Stahleck is now a hostel. Return to the riverside.

Km 541—Lorch: This pathetic stub of a castle is barely visible from the road. Check out the hillside vineyards. These vineyards once blanketed four times as much land as they do today, but modern economics have driven most of them out of business. The vineyards that do survive require government subsidies. Notice the small car ferry, one of several along the bridgeless stretch between Mainz and Koblenz.

Km 538—Sooneck Castle: Cross back to the other side of the train. Built in the 11th century, this castle was twice destroyed by people sick and tired of robber barons.

Km 534—Reichenstein Castle and Km 533—Rheinstein Castle: Stay on the other side of the train to see two of the first castles to be rebuilt in the Romantic era. Both are privately owned, tourable, and connected by a pleasant trail. Go back to the river side.

Km 530—Ehrenfels Castle: Opposite Bingerbrück and the Bingen station, you’ll see the ghostly Ehrenfels Castle (clobbered by the Swedes in 1636 and by the French in 1689). Since it had no view of the river traffic to the north, the owner built the cute little Mäuseturm (mouse tower) on an island (the yellow tower you’ll see near the train station today). Rebuilt in the 1800s in Neo-Gothic style, it’s now used as a Rhine navigation signal station.

Km 528—Niederwald Monument: Across from the Bingen station on a hilltop is the 120-foot-high Niederwald monument, a memorial built with 32 tons of bronze in 1877 to commemorate “the re-establishment of the German Empire.” A lift takes tourists to this statue from the famous and extremely touristy wine town of Rüdesheim.

From here, the Romantic Rhine becomes the industrial Rhine, and our tour is over.

Medieval invaders decided to give Marksburg a miss thanks to its formidable defenses. This best-preserved castle on the Rhine can be toured only with a guide on a 50-minute tour. In summer, tours in English normally run daily at 13:00 and 16:00. Otherwise, you can join a German tour (3/hour in summer, hourly in winter) that’s almost as good—there are no explanations in English in the castle itself, but your ticket includes an English handout. It’s an awesome castle, and between the handout and my commentary below, you’ll feel fully informed, so don’t worry about being on time for the English tours.

Cost and Hours: €7, family card-€16, daily 10:00-17:00, Nov-mid-March 11:00-16:00, last tour departs one hour before closing, tel. 02627/206, www.marksburg.de.

Getting There: Marksburg caps a hill above the village of Braubach, on the east bank of the Rhine. By train, it’s a 10-minute trip from Koblenz to Braubach (1-2/hour); from Bacharach or St. Goar, it can take up to two hours, depending on the length of the layover in Koblenz. The train is quicker than the boat (downstream from Bacharach to Braubach-2 hours, upstream return-3.5 hours; €30.40 one-way, €36.40 round-trip). Consider taking the downstream boat to Braubach, and the train back. If traveling with luggage, store it in the convenient lockers in the underground passage at the Koblenz train station (Braubach has no enclosed station—just platforms—and no lockers).

Once you reach Braubach, walk into the old town (follow Altstadt signs—coming out of tunnel from train platforms, it’s to your right); then follow the Zur Burg signs to the path up to the castle. Allow 25 minutes for the climb up. Scarce taxis charge at least €10 from the train platforms to the castle. A green tourist train circles up to the castle, but there’s no fixed schedule (Easter-mid-Oct Tue-Sun, no trains Mon or off-season, €3 one-way, €5 round-trip, leaves from Barbarastrasse, confirm departure times by calling 06773/587, www.ruckes-reisen.de). Even if you take the tourist train, you’ll still have to climb the last five minutes up to the castle from its parking lot.

Visiting the Castle: Your guided tour starts inside the castle’s first gate.

Inside the First Gate: While the dramatic castles lining the Rhine are generally Romantic rebuilds, Marksburg is the real McCoy—nearly all original construction. It’s littered with bits of its medieval past, like the big stone ball that was swung on a rope to be used as a battering ram. Ahead, notice how the inner gate—originally tall enough for knights on horseback to gallop through—was made smaller to deter enemies on horseback. Climb the Knights’ Stairway, carved out of slate, and pass under the murder hole—handy for pouring boiling pitch on invaders. (Germans still say someone with bad luck “has pitch on his head.”)

Coats of Arms: Colorful coats of arms line the wall just inside the gate. These are from the noble families who have owned the castle since 1283. In that year, financial troubles drove the first family to sell to the powerful and wealthy Katzenelnbogen family (who made the castle into what you see today). When Napoleon took this region in 1803, an Austrian family who sided with the French got the keys. When Prussia took the region in 1866, control passed to a friend of the Prussians who had a passion for medieval things—typical of this Romantic period. Then it was sold to the German Castles Association in 1900. Its offices are in the main palace at the top of the stairs.

Romanesque Palace: White outlines mark where the larger original windows were located, before they were replaced by easier-to-defend smaller ones. On the far right, a bit of the original plaster survives. Slate, which is vulnerable to the elements, needs to be covered—in this case, by plaster. Because this is a protected historic building, restorers can use only the traditional plaster methods...but no one knows how to make plaster that works as well as the 800-year-old surviving bits.

Cannons: The oldest cannon here—from 1500—was back-loaded. This was advantageous because many cartridges could be preloaded. But since the seal was leaky, it wasn’t very powerful. The bigger, more modern cannons—from 1640—were one piece and therefore airtight, but had to be front-loaded. They could easily hit targets across the river from here. Stone balls were rough, so they let the explosive force leak out. The best cannonballs were stones covered in smooth lead—airtight and therefore more powerful and more accurate.

Gothic Garden: Walking along an outer wall, you’ll see 160 plants from the Middle Ages—used for cooking, medicine, and witchcraft. Schierling (hemlock, in the first corner) is the same poison that killed Socrates.

Inland Rampart: This most vulnerable part of the castle had a triangular construction to better deflect attacks. Notice the factory in the valley. In the 14th century, this was a lead, copper, and silver mine. Today’s factory—Europe’s largest car-battery recycling plant—uses the old mine shafts as vents (see the three modern smokestacks).

Wine Cellar: Since Roman times, wine has been the traditional Rhineland drink. Because castle water was impure, wine—less alcoholic than today’s beer—was the way knights got their fluids. The pitchers on the wall were their daily allotment. The bellows were part of the barrel’s filtering system. Stairs lead to the...

Gothic Hall: This hall is set up as a kitchen, with an oven designed to roast an ox whole. The arms holding the pots have notches to control the heat. To this day, when Germans want someone to hurry up, they say, “give it one tooth more.” Medieval windows were made of thin sheets of translucent alabaster or animal skins. A nearby wall is peeled away to show the wattle-and-daub construction (sticks, straw, clay, mud, then plaster) of a castle’s inner walls. The iron plate to the left of the next door enabled servants to stoke the heater without being seen by the noble family.

Bedroom: This was the only heated room in the castle. The canopy kept in heat and kept out critters. In medieval times, it was impolite for a lady to argue with her lord in public. She would wait for him in bed to give him what Germans still call “a curtain lecture.” The deep window seat caught maximum light for needlework and reading. Women would sit here and chat (or “spin a yarn”) while working the spinning wheel.

Hall of the Knights: This was the dining hall. The long table is an unattached plank. After each course, servants could replace it with another pre-set plank. Even today, when a meal is over and Germans are ready for the action to begin, they say, “Let’s lift up the table.” The action back then consisted of traveling minstrels who sang and told of news gleaned from their travels.

Notice the outhouse—made of wood—hanging over thin air. When not in use, its door was locked from the outside (the castle side) to prevent any invaders from entering this weak point in the castle’s defenses.

Chapel: This chapel is still painted in Gothic style with the castle’s namesake, St. Mark, and his lion. Even the chapel was designed with defense in mind. The small doorway kept out heavily armed attackers. The staircase spirals clockwise, favoring the sword-wielding defender (assuming he was right-handed).

Linen Room: About the year 1800, the castle—with diminished military value—housed disabled soldiers. They’d earn a little extra money working raw flax into linen.

Two Thousand Years of Armor: Follow the evolution of armor since Celtic times. Because helmets covered the entire head, soldiers identified themselves as friendly by tipping their visor up with their right hand. This evolved into the military salute that is still used around the world today. Armor and the close-range weapons along the back were made obsolete by the invention of the rifle. Armor was replaced with breastplates—pointed (like the castle itself) to deflect enemy fire. This design was used as late as the start of World War I. A medieval lady’s armor hangs over the door. While popular fiction has men locking up their women before heading off to battle, chastity belts were actually used by women as protection against rape when traveling.

The Keep: This served as an observation tower, a dungeon (with a 22-square-foot cell in the bottom), and a place of last refuge. When all was nearly lost, the defenders would bundle into the keep and burn the wooden bridge, hoping to outwait their enemies.

Horse Stable: The stable shows off bits of medieval crime and punishment. Cheaters were attached to stones or pillories. Shame masks punished gossipmongers. A mask with a heavy ball had its victim crawling around with his nose in the mud. The handcuffs with a neck hole were for the transport of prisoners. The pictures on the wall show various medieval capital punishments. Many times the accused was simply taken into a torture dungeon to see all these tools, and, guilty or not, confessions spilled out of him. On that cheery note, your tour is over.

Easily reached from St. Goar, this lightweight exhibit reflects a little on Loreley, but focuses mainly on the landscape, culture, and people of the Rhine Valley. Though English explanations accompany most of the geological and cultural displays, the information about the famous mythical Mädchen is given in German only. The 3-D movie is essentially a tourist brochure for the region, with scenes of the grape harvest over Bacharach that are as beautiful as the sword-fighting is lame.

Far more exciting than the exhibit is the view from the cliffs themselves. A five-minute walk from the bus stop and visitors center takes you to the impressive viewpoint overlooking the Rhine Valley from atop the famous rock.

Cost and Hours: €2.50, daily April-Oct 10:00-17:00, closed Nov-March, café, tel. 06771/599-093, www.loreley-besucherzentrum.de.

Getting There: For a good hour’s hike, catch the ferry from St. Goar across to the village of St. Goarshausen (€1.80 each way, every 20 minutes daily until 22:30, less frequent on Sun). Then follow green Burg Katz (Katz Castle) signs up Burgstrasse under the train tracks to find steps on the right (Loreley über Burg Katz) leading to Katz Castle (privately owned) and beyond. Traverse the hillside, always bearing right toward the river. You’ll pass through a residential area, hike down a 50-yard path through trees, then cross a wheat field until you reach the Loreley Visitors Center and rock-capping viewpoint.

If you’re not up for a hike, catch bus #535 from just left of the St. Goarshausen ferry ramp (€2.90 each way, departs almost hourly, Easter-Oct Mon-Fri 8:45-18:45, Sat-Sun from 9:45).

To return to St. Goarshausen and the St. Goar ferry, you can take the bus (last departure 19:00), retrace your steps along the Burg Katz trail, or hike a steep 15 minutes directly down to the river, where the riverfront road takes you back to St. Goarshausen.

Next to the Loreley Visitors Center is the Loreley-Bob, a summer luge course (Sommerrodelbahn), with wheeled carts that seat one or two riders and whisk you down a stainless-steel track. It’s a fun diversion, especially if you don’t plan to visit the Tegelberg luge near Neuschwanstein or the scenic Biberwier luge in Austria.

Cost and Hours: €3/ride, €13 shareable 6-ride card; daily 10:00-17:00, closed mid-Nov-mid-March, may close in bad weather—call ahead, no children under age 3, ages 3-8 may ride with an adult, tel. 06771/959-4833 or 06651/9800, www.loreleybob.de.

This castle seems to rule its chunk of the Rhine from a commanding position. While its 13th-century exterior is medieval as can be, the interior is mostly a 19th-century duke’s hunting palace. Visitors wander freely (with an English flier) among trophies, armor, and Romantic Age decor.

Cost and Hours: €5.50; mid-March-Oct Mon 10:00-17:30, Tue-Sun 9:30-18:00; Nov-mid-March Sat-Sun only 12:00-16:00; tel. 06721/6348, www.burg-rheinstein.de.

Getting There: This castle (at km 533 marker, 2 km upstream from Trechtingshausen on the main B-9 highway) is easy by car (small, free parking lot on B-9, steep 5-minute hike from there), or bike (35 minutes upstream from Bacharach, stick to the great riverside path, after km 534 marker look for small Burg Rheinstein sign and Rösler-Linie dock). It’s less convenient by boat (no K-D stop nearby) or train (nearest stop in Trechtingshausen, a 30-minute walk away).

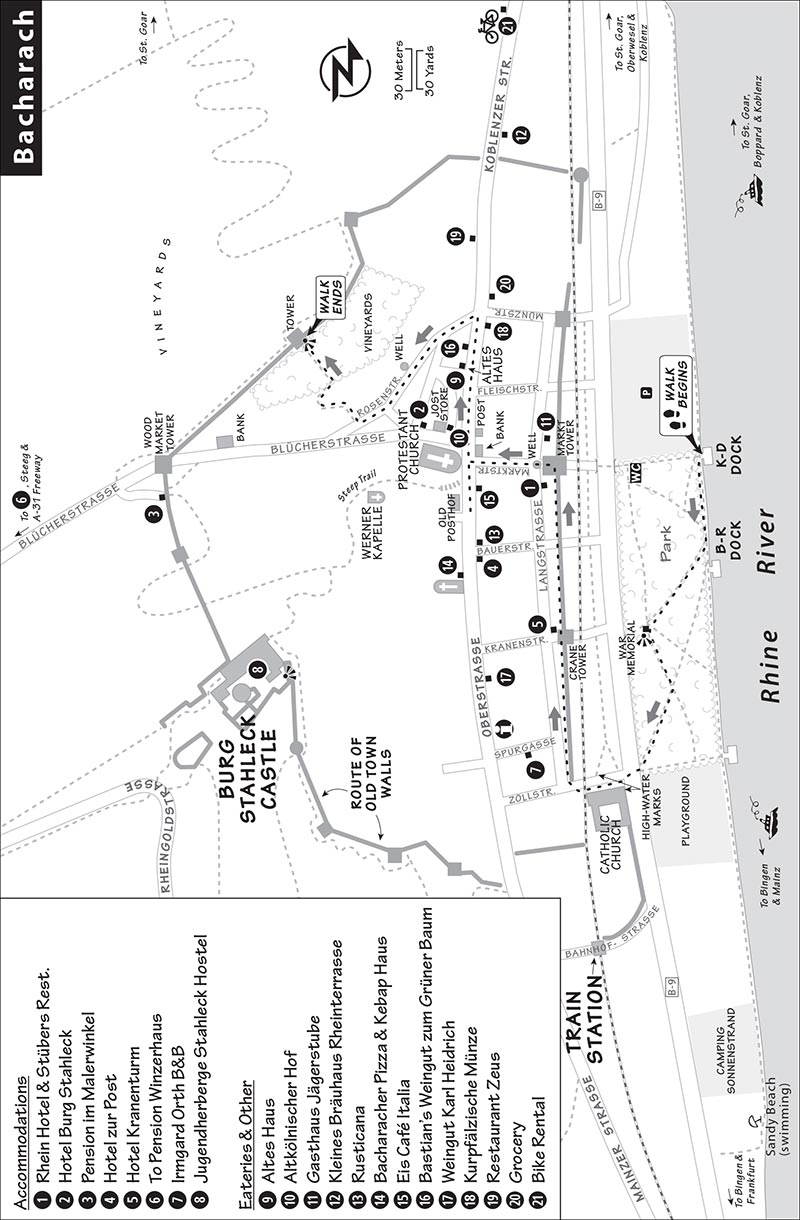

Once prosperous from the wine and wood trade, charming Bacharach (BAHKH-ah-rahkh, with a guttural kh sound) is now just a pleasant half-timbered village of 2,000 people working hard to keep its tourists happy. Businesses that have been “in the family” for eons are dealing with succession challenges, as the allure of big-city jobs and a more cosmopolitan life lure away the town’s younger generation. But Bacharach retains its time-capsule quaintness.

Bacharach cuddles, long and narrow, along the Rhine. The village is easily strollable—you can walk from one end of town to the other along its main drag, Oberstrasse, in about 10 minutes. Bacharach widens at its stream, where more houses trickle up its small valley (along Blücherstrasse) away from the Rhine. The hillsides above town are occupied by vineyards, scant remains of the former town walls, and a castle-turned-hostel.

The bright and well-stocked TI, on the main street a block-and-a-half from the train station, will store bags and bikes for day-trippers (April-Oct Mon-Fri 9:00-17:00, Sat-Sun 10:00-15:00; Nov-March Mon-Fri 9:00-13:00, closed Sat-Sun; from the train station, exit right and walk down the main street with the castle high on your left—the TI will be on your right at Oberstrasse 10; tel. 06743/919-303, www.bacharach.de or www.rhein-nahe-touristik.de, Herr Kuhn and his team).

Carry Cash: Although more places are accepting credit cards, come prepared to pay cash for most things in the Rhine Valley.

Shopping: The Jost German gift store, across the main square from the church, carries most everything a souvenir shopper could want—from beer steins to cuckoo clocks—and can ship purchases to the US (RS% with €10 minimum purchase: 10 percent with cash, 5 percent with credit card; open daily 9:00-18:00, closed Nov-Feb; Blücherstrasse 4, tel. 06743/909-7214).

Laundry: The Sonnenstrand campground may let you use their facilities even if you’re not staying there, but priority goes to those who are. Call ahead (tel. 06743/1752).

Picnics: You can pick up picnic supplies at Tomi’s, a basic grocery store (Mon-Fri 8:00-12:30 & 14:00-18:00, Sat 8:00-12:30, closed Sun, Koblenzer Strasse 2). For a gourmet picnic, call the recommended Rhein Hotel to reserve a “picnic bag” complete with wine, cheese, small dishes, and a hiking map (€15/person, arrange a day in advance, tel. 06743/1243).

Bike Rental: Some hotels loan bikes to guests. For bike rental in town, head to Rent-a-Bike Weber (€10/day, Koblenzer Strasse 35, tel. 06743-1898, mobile 0175-168073, heidi100450@aol.com).

Parking: It’s simple to park along the highway next to the train tracks or, better, in the big public lot by the boat dock (€4 from 9:00 to 18:00, pay with coins at Parkscheinautomat, display ticket on dash, free overnight).

Local Guides: Thomas Gundlach happily gives 1.5-hour town walks to individuals or small groups for €35. History buffs will enjoy his “war tour,” which focuses on the town’s survival from 1864 through World War II. He also offers 4- to 10-hour hiking or biking tours for the more ambitious (mobile 0179-353-6004, thomas_gundlach@gmx.de). Also good is Birgit Wessels (€45/1.5-hour walk, tel. 06743/937-514, wessels.birgit@t-online.de). The TI offers 1.5-hour tours in English with various themes, including a night tour (prices vary, gather a group). Or take my self-guided town walk or walk the walls—both are described next.

Taxi: Call Dirk Büttner at 06743/1653.

• Start this self-guided walk at the Köln-Düsseldorfer ferry dock (next to a fine picnic park).

Riverfront: View the town from the parking lot—a modern landfill. The Rhine used to lap against Bacharach’s town wall, just over the present-day highway. Every few years the river floods, covering the highway with several feet of water. Flat land like this is rare in the Rhine Valley, where towns are often shaped like the letter “T,” stretching thin along the riverfront and up a crease in the hills beyond.

Reefs farther upstream forced boats to unload upriver and reload here. Consequently, in the Middle Ages, Bacharach was the biggest wine-trading town on the Rhine. A riverfront crane hoisted huge kegs of prestigious “Bacharach” wine (which, in practice, was from anywhere in the region). Today, the economy is based on tourism.

Look above town. The castle on the hill is now a hostel. Two of the town’s original 16 towers are visible from here (up to five if you look really hard). The bluff on the right, with the yellow flag, is the Heinrich Heine Viewpoint (the end-point of a popular hike). Old-timers remember when, rather than the flag marking the town as a World Heritage site, a swastika sculpture 30 feet wide and tall stood there. Realizing that it could be an enticing target for Allied planes in the last months of World War II, locals tore it down even before Hitler fell.

Nearby, a stone column in the park describes the Bingen to Koblenz stretch of the Rhine gorge.

• Before entering the town, walk upstream through the...

Riverside Park: The park was originally laid out in 1910 in the English style: Notice how the trees were planted to frame fine town views, highlighting the most picturesque bits of architecture. Erected in 2016, a Picasso-esque sculpture by Bacharach artist Liesel Metten—of three figures sharing a bottle of wine (a Riesling, perhaps?)—celebrates three men who brought fame to the area through poetry and prose: Victor Hugo, Clemens Brentano, and Heinrich Heine. Other new elements of the park are designed to bring people to the riverside and combat flooding.

The dark, sad-looking monument—its “eternal” flame long snuffed out—is a war memorial. The German psyche is permanently scarred by war memories. Today, many Germans would rather avoid monuments like this, which recall the dark periods before Germany became a nation of pacifists. The military Maltese cross—flanked by classic German helmets—has a W at its center, for Kaiser Wilhelm. On the opposite side, each panel honors sons of Bacharach who died for the Kaiser: in 1864 against Denmark, in 1866 against Austria, in 1870 against France, in 1914 during World War I. Review the family names below: You may later recognize them on today’s restaurants and hotels.

• Look upstream from here to see (in the distance) the...

Trailer Park and Campground: In Germany, trailer vacationers and campers are two distinct subcultures. Folks who travel in motorhomes, like many retirees in the US, are a nomadic bunch, cruising around the countryside and paying a few euros a night to park. Campers, on the other hand, tend to set up camp in one place—complete with comfortable lounge chairs and TVs—and stay put for weeks, even months. They often come back to the same spot year after year, treating it like their own private estate. These camping devotees have made a science out of relaxing. Tourists are welcome to pop in for a drink or meal at the campground café (see “Activities in Bacharach,” later).

• Continue to where the park meets the playground, and then cross the highway to the fortified riverside wall of the Catholic church, decorated with...

High-Water Marks: These recall various floods. Before the 1910 reclamation project, the river extended out to here, and boats would tie up at mooring rings that used to be in this wall.

• From the church, go under the 1858 train tracks (and past more high-water marks) and hook right up the stairs at the yellow floodwater yardstick to reach the town wall. Atop the wall, turn left and walk under the long arcade. After 30 yards, on your left, notice a...

Well: Rebuilt as it appeared in the 17th century, this is one of seven such wells that brought water to the townsfolk until 1900. Each neighborhood’s well also provided a social gathering place and the communal laundry. Walk 50 yards past the well along the wall to an alcove in the medieval tower with a view of the war memorial in the park. You’re under the crane tower (Kranenturm). After barrels of wine were moved overland from Bingen, avoiding dangerous stretches of river, the precious cargo could be lowered by cranes from here into ships to continue more safely down the river. The Rhine has long been a major shipping route through Germany. In modern times, it’s a bottleneck in Germany’s train system. The train company gives hotels and residents along the tracks money for soundproof windows.

• Continue walking along the town wall. Pass the recommended Rhein Hotel just before the...

Markt Tower: This marks one of the town’s 15 original 14th-century gates and is a reminder that in that century there was a big wine market here.

• Descend the stairs closest to the Rhein Hotel, pass another well, and follow Marktstrasse away from the river toward the town center, the two-tone church, and the town’s...

Main Intersection: From here, Bacharach’s main street (Oberstrasse) goes right to the half-timbered red-and-white Altes Haus (which we’ll visit later) and left 400 yards to the train station. Spin around to enjoy the higgledy-piggledy building styles. The town has a case of the doldrums: The younger generation is moving to the big cities and many long-established family businesses have no one to take over for their aging owners. In the winter the town is particularly dead.

• To the left (south) of the church, a golden horn hangs over the old...

Posthof: Throughout Europe, the postal horn is the symbol of the postal service. In olden days, when the postman blew this, traffic stopped and the mail sped through. This post station dates from 1724, when stagecoaches ran from Cologne to Frankfurt and would change horses here, Pony Express-style. Notice the cornerstones at the Posthof entrance, protecting the venerable building from reckless carriage wheels. If it’s open, inside the old oak doors (on the left) is the actual door to the post office that served Bacharach for 200 years. Find the mark on the wall labeled Rheinhöhe 30/1-4/2 1850. This recalls a historic flood caused by an ice jam at the Loreley just downstream. Notice also the fascist eagle in the alcove on the right (from 1936; a swastika once filled its center). The courtyard was once a carriage house and inn that accommodated Bacharach’s first VIP visitors.

Two hundred years ago, Bacharach’s main drag was the only road along the Rhine. Napoleon widened it to fit his cannon wagons. The steps alongside the church lead to the ruins of the 15th-century Werner Chapel and the castle.

• Return to the church, passing the recommended Italian ice-cream café (Eis Café Italia), where friendly Mimo serves his special invention: Riesling wine-flavored gelato.

Protestant Church: Inside the church (daily 10:00-18:00, closed Nov-March, English info on a stand near door), you’ll find grotesque capitals, brightly painted in medieval style, and a mix of round Romanesque and pointed Gothic arches. The church was fancier before the Reformation wars, when it (and the region) was Catholic. Bacharach lies on the religious border of Germany and, like the country as a whole, is split between Catholics and Protestants. To the left of the altar, some medieval (pre-Reformation) frescoes survive where an older Romanesque arch was cut by a pointed Gothic one.

If you’re considering bombing the town, take note: A blue-and-white plaque just outside the church’s door warns that, according to the Hague Convention, this historic building shouldn’t be targeted in times of war.

• Continue down Oberstrasse to the...

Altes Haus: Dating from 1389, this is the oldest house in town. Notice the 14th-century building style—the first floor is made of stone, while upper floors are half-timbered (in the ornate style common in the Rhine Valley). Some of its windows still look medieval, with small, flattened circles as panes (small because that’s all that the glass-blowing technology of the time would allow), pieced together with molten lead (like medieval stained glass in churches). Frau Weber welcomes visitors to enjoy the fascinating ground floor of the recommended Altes Haus restaurant, with its evocative old photos and etchings (consider eating here later).

• Keep going down Oberstrasse to the...

Old Mint (Münze): The old mint is marked by a crude coin in its sign. As a practicality, any great trading town needed coinage, and since 1356, Bacharach minted theirs here. Now, it’s a restaurant and bar, Kurpfälzische Münze, with occasional live music. Across from the mint, the recommended Bastian family’s wine garden is another lively place in the evening (see “Nightlife in Bacharach” and “Wine Tasting,” later). Above you in the vineyards stands a lonely white-and-red tower—your final destination.

• At the next street, look right and see the mint tower, painted in the medieval style, and then turn left. Wander 30 yards up Rosenstrasse to the well. Notice the sundial and the wall painting of 1632 Bacharach with its walls intact. Study the fine slate roof over the well: The town’s roof tiles were quarried and split right here in the Rhineland. Continue another 30 yards up Rosenstrasse to find the tiny-stepped lane on the right leading up into the vineyard and to the...

Tall Tower: The slate steps lead to a small path through the vineyard that deposits you at a viewpoint atop the stubby remains of the medieval wall and a tower. The town’s towers jutted out from the wall and had only three sides, with the “open” side facing the town. Towers were covered with stucco to make them look more impressive, as if they were made of a finer white stone. If this tower’s open, hike up to climb the stairs for the best view. (The top floor has been closed to give nesting falcons some privacy.)

Romantic Rhine View: Looking south, a grand medieval town spreads before you. For 300 years (1300-1600), Bacharach was big (population 4,000), rich, and politically powerful.

From this perch, you can see the ruins of a 15th-century chapel and six surviving city towers. Visually trace the wall to the Stahleck Castle. The castle was actually the capital of Germany for a couple of years in the 1200s. When Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa went away to fight the Crusades, he left his brother (who lived here) in charge of his vast realm. Bacharach was home to one of the seven electors who voted for the Holy Roman Emperor in 1275. To protect their own power, these prince electors did their best to choose the weakest guy on the ballot. The elector from Bacharach helped select a two-bit prince named Rudolf von Habsburg (from a no-name castle in Switzerland). However, the underestimated Rudolf brutally silenced the robber barons along the Rhine and established the mightiest dynasty in European history. His family line, the Habsburgs, ruled much of Central and Eastern Europe from Vienna until 1918.

Plagues, fires, and the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648) finally did in Bacharach. The town has slumbered for several centuries. Today, the castle houses commoners—40,000 overnights annually by hostelers.

In the mid-19th century, painters such as J. M. W. Turner and writers such as Victor Hugo were charmed by the Rhineland’s romantic mix of past glory, present poverty, and rich legend. They put this part of the Rhine on the old Grand Tour map as the “Romantic Rhine.” Hugo pondered the chapel ruins that you see under the castle: In his 1842 travel book, Excursions Along the Banks of the Rhine, he wrote, “No doors, no roof or windows, a magnificent skeleton puts its silhouette against the sky. Above it, the ivy-covered castle ruins provide a fitting crown. This is Bacharach, land of fairy tales, covered with legends and sagas.” If you’re enjoying the Romantic Rhine, thank Victor Hugo and company.

• Our walk is done. To get back into town, just retrace your steps. Or, to extend this walk, take the level path away from the river that leads along the once-mighty wall up the valley to the next tower, the...

Wood Market Tower: Timber was gathered here in Bacharach and lashed together into vast log booms known as “Holland rafts” (as big as a soccer field) that were floated downstream. Two weeks later the lumber would reach Amsterdam, where it was in high demand as foundation posts for buildings and for the great Dutch shipbuilders. Notice the four stones above the arch on the uphill side of the tower—these guided the gate as it was hoisted up and down.

• From here, cross the street and go downhill into the parking lot. Pass the recommended Pension im Malerwinkel on your right, being careful not to damage the old arch with your head. Follow the creek past a delightful little series of half-timbered homes and cheery gardens known as “Painters’ Corner” (Malerwinkel). Resist looking into some weirdo’s peep show (on the right) and continue downhill back to the village center.

A steep and rocky but clearly marked walking path follows the remains of Bacharach’s old town walls and makes for a good hour’s workout. There are benches along the way where you can pause and take in views of the Rhine and Bacharach’s slate roofs. The TI has maps that show the entire route. The path starts near the train station, climbs up to the hostel in what was Stahleck Castle (serves lunch from 12:00-13:30), descends into the side valley, and then continues up the other side to the tower in the vineyards before returning to town. To start the walk at the train station, find the house at Oberstrasse 2 and climb up the stairway to its left. Then follow the Stadtmauer-Rundweg signs. Good bilingual signposts tell the history of each of the towers along the wall—some are intact, one is a private residence, and others are now only stubs.

This campground, a 10-minute walk upstream from Bacharach, has a sandy beach with water as still as a lake, and welcomes non-campers (especially if you buy a drink at their café). On hot summer days you can enjoy a dip in the Rhine at the beach at your own risk (free, no lifeguard—beware of strong current). This is a chance to see Euro-style camping, which comes with a sense of community. Campers are mostly Dutch, English, Belgian, and German, with lots of kids (and a playground). The $ terrace café overlooking the campsites and the river is the social center and works well for a drink or meal (inside or outside with river view, daily 17:00-21:00, closed Nov-March, tel. 06743/1752, www.camping-rhein.de).

The only listings with parking are Pension im Malerwinkel, Pension Winzerhaus, and the hostel. For the others, you can drive in to unload your bags and then park in the public lot (see “Helpful Hints,” earlier). If you’ll arrive after 20:00, let your hotel know in advance (many hotels with restaurants stay open late, but none have 24-hour reception desks).

$$ Rhein Hotel, overlooking the river with 14 spacious and comfortable rooms, is classy, well-run, and decorated with modern flair. This place has been in the Stüber family for six generations and is decorated with works of art by the current owner’s siblings. The large family room downstairs is über stylish, while the quaint “hiker room” on the top floor features terrific views of both the town and river. You can sip local wines in the renovated room where owner Andreas was born (river- and train-side rooms come with quadruple-paned windows and air-con, in-room sauna, packages available including big three-course dinner, ask about “picnic bags” when you check in, free loaner bikes, directly inland from the K-D boat dock at Langstrasse 50, tel. 06743/1243, www.rhein-hotel-bacharach.de, info@rhein-hotel-bacharach.de). Their recommended Stübers Restaurant is considered the best in town.

$$ Hotel Burg Stahleck, above a cozy café in the town center, rents five big, bright rooms, more chic than shabby. Birgit treats guests to homemade cakes at breakfast (family rooms, view room, free parking, cheaper rooms in guesthouse around the corner, Blücherstrasse 6, tel. 06743/1388, www.urlaub-bacharach.de, info@urlaub-bacharach.de).

$ Pension im Malerwinkel sits like a grand gingerbread house that straddles the town wall in a quiet little neighborhood so charming it’s called “Painters’ Corner” (Malerwinkel). The Vollmer family’s super-quiet 20-room place is a short stroll from the town center. Here guests can sit in a picturesque garden on a brook and enjoy views of the vineyards (cash only, family rooms, elevator, no train noise, bike rentals, easy parking; from Oberstrasse, turn left at the church, walkers can follow the path to the left just before the town gate but drivers must pass through the gate to find the hotel parking lot, Blücherstrasse 41; tel. 06743/1239, www.im-malerwinkel.de, pension@im-malerwinkel.de, Armin and Daniela).

$ Hotel zur Post, refreshingly clean and quiet, is conveniently located right in the town center with no train noise. Its 12 rooms are a good value. Run by friendly and efficient Ute, the hotel offers more solid comfort than old-fashioned character, though the lovely wood-paneled breakfast room has a rustic feel (family room, Oberstrasse 38, tel. 06743/1277, www.hotel-zur-post-bacharach.de, h.zurpost@t-online.de).

$ Hotel Kranenturm, part of the medieval town wall, has 16 rooms with rustic castle ambience and Privatzimmer funkiness right downtown. The rooms in its former Kranenturm (crane tower) have the best views. While just 15 feet from the train tracks, a combination of medieval sturdiness and triple-paned windows makes the riverside rooms sleepable (RS%, family rooms, Rhine views come with train noise—earplugs on request, back rooms are quieter, closed Jan-Feb, Langstrasse 30, tel. 06743/1308, mobile 0176-8056-3863, www.kranenturm.com, hotel.kranenturm@gmail.com).

$ Pension Winzerhaus, a 10-room place run by friendly Sybille and Stefan, is just outside the town walls, directly under the vineyards. The rooms are simple, clean, and modern, and parking is a breeze (cash only, family room, laundry service, parking, nondrivers may be able to arrange a pickup at the train station—ask in advance, Blücherstrasse 60, tel. 06743/1294, www.pension-winzerhaus.de, winzerhaus@gmx.de).

¢ Irmgard Orth B&B rents three bright rooms, two of which share a small bathroom on the hall. Charming Irmgard speaks almost no English, but is exuberantly cheery and serves homemade honey with breakfast (cash only, Spurgasse 2, tel. 06743/1553—speak slowly; she prefers email: orth.irmgard@gmail.com).

¢ Jugendherberge Stahleck hostel is a 12th-century castle on the hilltop—350 steps above Bacharach—with a royal Rhine view. Open to travelers of any age, this gem has 36 rooms, eight with private showers and WCs. The hostel offers hearty all-you-can-eat buffet dinners (18:00-19:30 nightly); in summer, its bistro serves drinks and snacks until 22:00. If you arrive at the train station with luggage, it’s a minimum €10 taxi ride to the hostel—call 06743/1653 (pay Wi-Fi, reception open 7:00-20:00—call if arriving later, tel. 06743/1266, www.diejugendherbergen.de, bacharach@diejugendherbergen.de, Samuel). If driving, don’t go in the driveway; park on the street and walk 200 yards.

Bacharach has several reasonably priced, atmospheric restaurants offering fine indoor and outdoor dining. Most places don’t take credit cards.

The recommended Rhein Hotel’s $$$ Stübers Restaurant is Bacharach’s best top-end choice. Andreas Stüber, his family’s sixth-generation chef, creates regional plates prepared with a slow-food ethic. The menu changes with the season and is served at river- and track-side seating or indoors with a spacious wood-and-white-tablecloth elegance. Consider the William Turner pâté starter plate, named after the British painter who liked Bacharach. Book in advance for the special Tuesday slow-food menu (discount for hotel guests, always good vegetarian and vegan options, daily 17:00-21:30 plus Sun 11:30-14:15, closed mid-Dec-Feb, call or email to reserve on weekends or for an outdoor table when balmy, family-friendly with a play area, Langstrasse 50, tel. 06743/1243, info@rhein-hotel-bacharach.de). Their Posten Riesling is well worth the splurge and pairs well with both the food and the atmosphere.

$$$ Altes Haus, the oldest building in town (see the “Bacharach Town Walk,” earlier), serves classic German dishes within Bacharach’s most romantic atmosphere. Find the cozy little dining room with photos of the opera singer who sang about Bacharach, adding to its fame (Thu-Tue 12:00-14:30 & 18:00-21:30, Mon dinner only, limited menu and closes at 18:00 on weekends, closed Wed and Dec-Easter, dead center by the Protestant church, tel. 06743/1209).

$$$ Altkölnischer Hof is a family-run place with outdoor seating right on the main square, serving Rhine specialties that burst with flavor. This restored 18th-century banquet hall feels formal and sophisticated inside, with high ceilings and oil paintings depicting the building’s history. Reserve an outdoor table for a more relaxed meal, especially on weekends when locals pack the place (Tue-Sun 12:00-14:30 & 17:30-21:00, closed Mon and Nov-Easter, Blücherstrasse 2, tel. 06743/947-780, www.altkoelnischer-hof.de).

$$ Gasthaus Jägerstube is every local’s nontouristy, good-value hangout. It’s a no-frills place run by a former East German family determined to keep Bacharach’s working class well-fed and watered. Next to the WC is a rare “party cash box.” Regulars drop money into their personal slot throughout the year, Frau Tischmeier banks it, and by year’s end...there’s plenty in the little savings account for a community party (Wed-Mon March-Nov 11:00-22:00, food served until 21:30; Dec-Feb from 15:00, food served until 20:30; closed Tue year-round; Marktstrasse 3, tel. 06743/1492, Tischmeier family).

$$ Kleines Brauhaus Rheinterrasse is a funky microbrewery serving hearty meals, fresh-baked bread, and homemade beer under a 1958 circus carousel that overlooks the town and river. Sweet Annette cooks while Armin brews, and the kids run free in this family-friendly place. For a sweet finish, try the “beer-liquor,” which tastes like Christmas. Don’t leave without putting €0.20 in the merry-go-round-in-a-box in front of the Rhine Theater next door (Tue-Sun 13:00-22:00, closed Mon, at the downstream end of town, Koblenzer Strasse 14, tel. 06743/919-179). The little flea market in the attached shed seems to fit right in.

$$ Rusticana, draped in greenery, is an inviting place serving homestyle German food and apple strudel that even the locals swear by. Sit on the delightful patio or at cozy tables inside (daily 11:00-20:00, credit cards accepted, Oberstrasse 40, tel. 06743/1741).

$ Bacharacher Pizza and Kebap Haus, on the main drag, is the town favorite for döner kebabs, cheap pizzas, and salads. Imam charges the same to eat in or take out (daily 11:00-22:00, Oberstrasse 43, tel. 06743/3127).

Camping Sonnenstrand, a 10-minute walk from town, has a café (dinner only) with great river views inside and out (see “Activities in Bacharach,” earlier).

Gelato: Right on the main street, Eis Café Italia is run by friendly Mimo Calabrese, who brought gelato to town in 1976. He’s known for his refreshing, not-too-sweet Riesling-flavored gelato. He also makes one with rose petals from a nearby farm. Eat in or take it on your evening stroll (no tastes offered, homemade, Waldmeister flavor is made with forest herbs—top secret, daily 13:00-19:00, closed mid-Oct-March, Oberstrasse 48).

Bacharach is proud of its wine. Two places in town—Bastian’s rowdy and rustic Grüner Baum, and the more sophisticated Weingut Karl Heidrich—offer visitors an inexpensive tasting memory. Each creates carousels of local wines that small groups of travelers (who don’t mind sharing a glass) can sample and compare. Both places offer light plates of food if you’d like a rustic meal.

At $$ Bastian’s Weingut zum Grüner Baum, pay €29.50 for a wine carousel of 12 glasses—nine different white wines, two reds, and one lonely rosé—and a basket of bread. Your mission: Meet up here after dinner with others who have this book. Spin the Lazy Susan, share a common cup, and discuss the taste. The Bastian family insists: “After each wine, you must talk to each other” (daily 12:00-22:00, Nov-Dec closed Mon-Wed, closed Jan-Feb, just past Altes Haus, tel. 06743/1208). To make a meal of a carousel, consider the Käseschmaus (seven different cheeses—including Spundekäse, the local soft cheese—with bread and butter). Along with their characteristic interior, they have three nice terraces (front for shade, back for sun, and a courtyard).

$$ Weingut Karl Heidrich is a fun family-run wine shop and Stube in the town center, where Markus and daughters Magdalena and Katharina proudly share their family’s centuries-old wine tradition, explaining its fine points to travelers. They offer a variety of €14.50 carousels with six wines, English descriptions, and bread—ideal for the more sophisticated wine taster—plus light meals and a meat-and-cheese plate (Thu-Mon 12:00-22:00, kitchen closes at 21:00, closed Tue-Wed and Nov-mid-April, Oberstrasse 16, will ship to the US, tel. 06743/93060, info@weingut-karl-heidrich.de). With advance notice, they’ll host a wine tasting and hike for groups (€185/up to 15 people).

Bacharach goes to bed early, so your options are limited for a little after-dinner action. But a handful of local bars/restaurants and two wine places (listed in “Wine Tasting,” earlier) are welcoming and can be fun in the late hours.

$$ Kurpfälzische Münze (Old Mint) has live music some nights, ranging from jazz and blues to rock to salsa, and pairs local wines with meat-and-cheese plates and other local specialties (daily 12:00-24:00, Nov-March from 18:00). Gasthaus Jägerstube (described earlier) is a good pick for those who want to mix with a small local crowd. $$ Restaurant Zeus’s delicious Greek fare, long hours, and outdoor seating add a spark to the city center after dark (daily 17:30-24:00, cash only, Koblenzer Strasse 11, tel. 06743/909-7171). For something a bit off the beaten path try Jugendherberge Stahleck—Bacharach’s hostel—where the bistro serves munchies and drinks with priceless views until 22:00 in summer (listed earlier, under “Sleeping in Bacharach”).

Milk-run trains stop at Rhine towns each hour starting as early as 6:00, connecting at Mainz and Koblenz to trains farther afield. Trains between St. Goar and Bacharach depart at about :50 after the hour in each direction (buy tickets from the machine in the unstaffed stations, carry cash since some machines won’t accept US credit cards).

The durations listed below are calculated from Bacharach; for St. Goar, the difference is only 10 minutes. From Bacharach (or St. Goar), to go anywhere distant, you’ll need to change trains in Koblenz for points north, or in Mainz for points south. Milk-run connections to these towns depart hourly, at about :50 past the hour for northbound trains, and at about :05 past the hour for southbound trains (with a few more on the half hour). Train info: www.bahn.com.

From Bacharach by Train to: St. Goar (hourly, 10 minutes), Moselkern near Burg Eltz (hourly, 1.5 hours, change in Koblenz), Cochem (hourly, 2 hours, change in Koblenz), Trier (hourly, 3 hours, change in Koblenz), Cologne (hourly, 2 hours with change in Koblenz, 2.5 hours direct), Frankfurt Airport (hourly, 1 hour, change in Mainz or Bingen), Frankfurt (hourly, 1.5 hours, change in Mainz or Bingen), Rothenburg ob der Tauber (every 2 hours, 4.5 hours, 3-4 changes), Munich (hourly, 5 hours, 2 changes), Berlin (every 2 hours with a transfer in Frankfurt, 5.5 hours; more with 2-3 changes), Amsterdam (hourly, 5-7 hours, change in Cologne, sometimes 1-2 more changes).

This area is a logical first (or last) stop in Germany. If you’re using Frankfurt Airport, here are some tips.

Frankfurt Airport to the Rhine: Driving from Frankfurt to the Rhine or Mosel takes about an hour (follow blue autobahn signs from airport—major cities are signposted).

The Rhine to Frankfurt: From St. Goar or Bacharach, follow the river to Bingen, then autobahn signs to Mainz, then Frankfurt. From there, head for the airport (Flughafen) or downtown (signs to Messe, then Hauptbahnhof, to find the parking under Frankfurt’s main train station—see “Arrival in Frankfurt—By Car” on here).

Oberwesel (OH-behr-vay-zehl), with more commerce than St. Goar and Bacharach combined, is just four miles from Bacharach. Oberwesel was a Celtic town in 400 BC, then a Roman military station. It’s worth a quick visit, with a charming main square, a fun-to-walk medieval wall, and the best collection of historic Rhine artifacts I’ve found within the Rhine Valley. From the river, you’ll notice its ship’s masts rising from terra firma—a memorial to the generations of riverboat captains and sailors for whom this town is famous. Like most towns on the Rhine, Oberwesel is capped by a castle (Schönburg, now a restaurant, hotel, and youth hostel with a small museum). The other town landmark is its 130-foot-tall crenellated Ochsenturm (Oxen Tower), standing high and solitary overlooking the river.

Oberwesel is an easy stop by boat, train, bike, or car from Bacharach. There’s free parking by the river (as is often the case in small towns, you must display a plastic clock—see here).

Exploring Oberwesel is a breeze when you follow my self-guided walk. Start out by picking up a map from the TI on the main square (closed Sun, 10-minute walk from the train station at Rathausstrasse 3—from the station turn right and follow Liebfrauenstrasse to Marktplatz, tel. 06744/710-624, www.oberwesel.de). Maps are also available at the Kulturhaus and Stadtmuseum Oberwesel, and posted around town—just snap a photo of one to use as a guide.

I’ve laced together Oberwesel’s sights with this self-guided walk. Allow at least an hour without stops. Here’s an overview: Starting at the Marktplatz, you’ll visit the museum and hike the lower wall to the Ochsenturm at the far end of town, then climb to the top of the town and walk the upper wall, passing through the Stadtmauergarten and Klostergarten (former monastery) before returning to the Marktplatz, where you can get a bite to eat at one of several cafés.

• Begin at the Marktplatz in front of the TI.

Marktplatz: For centuries this has been Oberwesel’s social and commercial center. That tradition continues today in the Marktplatz’s tourist-friendly cafés and wine bars. If you’re here in the summer, you can’t miss the oversized wine glass declaring that Oberwesel is a winegrowers’ town. Around harvest time, the city hosts a huge wine festival and elects a “Wine Witch.” Why? It’s pure marketing. After World War II, the Rhine’s wine producers were desperate to sell their wine, so they hosted big parties and elected a representative. All the other towns picked wine queens, but Oberwesel went with a witch instead.

• Continue along the main drag, passing several cafés, until you see the entrance (marked Eingang) for the museum on the left.

Kulturhaus and Stadtmuseum Oberwesel: This is the region’s best museum on local history and traditions, with lots of artifacts and interesting exhibits. The ground floor retraces the history of Oberwesel, from the Romans to the 19th-century Romantics. Upstairs you’ll learn how salmon were once fished here, and timber traders lashed together huge rafts of wood and floated them to the Netherlands to sell. You’ll see dramatic photos of the river when it was jammed with ice, and review wine witches from the past few decades (€3, Tue-Fri 10:00-17:00, Sat-Sun from 14:00, closed Mon; Nov-March Tue-Fri until 14:00, closed Sat-Mon; borrow the English descriptions, Rathausstrasse 23, tel. 06744/7147-26, www.kulturhaus-oberwesel.de).

• Return to the Marktplatz, turn toward the river and walk to the...

Town Wall: The walls in front of you are some of the best-preserved walls in the Middle Rhine Valley, thanks to the work of a group of local citizen volunteers.

• Turn right on Rheinstrasse, climb the narrow steps on the left to the top of the wall, and start walking downstream (left), toward the leaning tower.

Hospitalgassenturm (Hospital Tower) and Vineyards: This tower was initially constructed to rest on the wall. But it was too heavy. In an attempt to “fix it,” they straightened out the top.

Notice the vineyards along the banks of the Rhine. They’ve been part of the landscape here for centuries. Recently, many vintners have been letting the vineyards go untended, as they are just too expensive to keep up. The hope is that a younger generation will bring new energy to the Rhineland’s vineyards. But the future of these fabled vineyards remains uncertain.

• Continue walking until you come to the...

Werner-Kapelle (Hospital Chapel): This chapel was built into the wall in the 13th century and remains part of the hospital district to this day. The sick lay in bed here with their eyes on the cross, confident that a better life awaited them in heaven. Today this chapel serves the adjacent, more modern hospital (free, daily 9:00-17:00).

• Continue walking along the wall to reach the next tower. Climb up if you’d like.

Steingassenturm: This tower is named for the first paved road in town, just ahead. Inside the tower, notice the little holes about six feet up. This is where they placed the scaffolding during construction. If you climb to the top, consider how many Romantic painters and poets in centuries past enjoyed this same view.

As Victor Hugo wrote, “This is the warlike Oberwesel whose old walls are riddled with the havoc of shot and shells. Upon them you easily recognize the trace of the huge cannon balls of the bishops of Treves, the Biscayans of Louis XIV, and the revolutionary grape shot of France. At the present day Oberwesel resembles an old veteran soldier turned winemaker, and what excellent wine he produces.”

• Carry on toward the two towers in the distance. Just before the break in the wall, stop to take in the view.

View of the Katzenturm (Cat Tower) and Ochsenturm (Oxen Tower): These were among the 16 towers that once protected Oberwesel. The farthest tower, Ochsenturm, was built in the 14th century as a lookout and signal tower, but its eight-sided design and crenellated top were also a status symbol for the archbishop, declaring his power to all who passed here along the Rhine. The tower still impresses passersby today.

Take a moment here, with all the ships and trains going by, to think about transportation on the Rhine across the centuries. The Rhine has been a major transportation route since Roman times, when the river marked the northern end of the empire. The Rhineland’s many castles and fortifications, like the one above Oberwesel, testify to its strategic importance in the Middle Ages. The stretch from Koblenz to Bingen was home to no fewer than 16 greedy dukes and lords—robber barons running two-bit dukedoms, living in hilltop castles and collecting tolls from merchant vessels passing by in the river below.

Between you and the river are: a bike lane (once a towpath for mighty horses pulling boats upstream), a train line (one of the first in Germany), and the modern road (built in the 1950s). Until modern times there was just one small road through Oberwesel—the one you walked along to get to the center of town.

Have you heard the trains passing by? Increasing rail traffic has made nearly constant train noise quite an issue for Rhinelanders. It’s estimated that, on average, a train barrels down each side of the Rhine every three minutes. That’s 500 trains a day. Landowners complain that it’s nearly impossible to sell a piece of property along this stretch due to the train noise.

• A set of stairs takes you down to street level. Notice the white church on the hilltop to your left—that’s where you’re headed, to continue this walk with a visit to the upper town walls. To get there, walk straight ahead along Niederbachstrasse. Go under the arch and make an immediate left to walk through the Kölnischer Torturm (Cologne Gate Tower). Follow Kölnische Turmgasse two blocks to find a staircase to your right, leading up to the church. Ascend the stairs and stop at the top to enjoy the view.

St. Martin’s Church: Built in the 14th century, this is one of two major churches in town and is known to townspeople as the “white church.” Although it looks like sandstone, it’s actually made of more readily available slate. Notice the picturesque little church-caretaker’s house to the left, then ascend the small set of stairs to the church.

• Walk around the left side of the church and peek inside. Then continue around the back of the building through the gate to the gardens overlooking the Rhine.