Introduction

Q) Why is the Trabant the quietest car in the world to drive?

A) Because your knees cover your ears.

Why?

Even though he’d pulled us over, the policeman looked more confused than angry. He approached our convoy slowly in the snow, scratching his head and shining his torch along the faded, peeling panelling of the cars. The beam reached my face, making me blink away.

“Where are you from?” he asked in Russian.

“England.”

“Where are you going?”

“Cambodia.”

“Kaamboodyaa?” He rolled the word out, making it sound unfamiliar.

“Cam-bo-dia.”

“Ahhh… Cambodia,” he repeated, understanding the name, but not the answer.

“Why?”

Why? That was difficult.

The policeman shrugged and held up his camera phone, “Photo?”

The Email

I remember getting the email. Autumn 2006. I’d returned home late after a few post-deadline drinks, and sat on my bed with a laptop. The message was from John Lovejoy. The subject line read: “Europe to Cambodia by Trabant.”

Team USA

John Christian Lovejoy was a man of the world. Born in California, but raised at US Army bases in Germany, he had travelled extensively and boasted of friends across the globe. Tall, handsome, with a thick mop of curly hair and an occasional beard, he was a real charmer with a handy knack for getting people onside and a shameless approach to milking acquaintances.

His favourite word was “fuck”. Used mostly for emphasis, it could be a noun, adjective, preposition, verb or anything he desired. As in: “What the fuck? Let’s get the fuck back to that fucking place and get a fucking burger. I mean fuck. With that fucking sauce. Fuck me, man. It’s fucking rad and it’s fucking cheap. It’s like what? Fucking two dollars?”

To maintain some sense of decency I have omitted many of these superfluous curses from his quotes. Sorry, Lovey.

I first met Lovejoy with his friend Anthony Perez in 2002 in the sticky Thai jungle somewhere north of Chang Mai. Along with my travel buddy, Mr Al, I’d headed out on an organised trek into the bush. We’d noticed the two Americans when the group gathered earlier that day, but it took until a rest stop at a waterfall to make conversation. Mr Al and I had brought with us a bottle of the filthy local Mekong whisky; a vicious brown poison that cost next to nothing and doubled up as nail varnish remover. It was disgusting neat and, looking around for some inspiration, I noticed the Americans sipping from a bottle of Coke. From this whisky and Coke a partnership was born, and we bonded over three days of sweaty walks and cool waterfalls.

I was 19 at the time; Lovey, as Lovejoy was known, and Tony were a few years older. The pair knew each other from Washington DC, where they lived and worked, and had an easy rapport.

“You know,” Tony would tell me years later, “Lovey’s the only person I’ve travelled with where I can just go ‘John, I’m going to go and do my own thing for a few weeks now. I’ll catch you later’ and he’ll be absolutely fine with it.”

Tony was half-Mexican, half-Italian but very American. Shorter than Lovey, but compact and dark, he liked to sport a Mohican and a moustache, which made him look a little Mongolian. The four of us got on well and when we waved our goodbyes I jokingly said I’d see them further on down the trail. Three weeks later and I was on the back of a Vietnamese moped, speeding through Ho Chi Minh City trying to flag down a bus to Cambodia. We were close up behind it, my driver honking manically and trying to get the bus to stop, when a rear window slid open and the dark head of Tony Perez popped out.

“Dan?” he said with a smile.

“Tony,” I shouted over the traffic.

“How’s it going?” he asked, cool as you like.

“Yeah great… er… I’m trying to get on that bus.”

He looked around, dragged it out for a second, then grinned: “I’ll get them to stop.”

It turned out that Tony and I were heading the same way. We met Lovey in Phnom Penh, then continued to Siem Riep for a few days at Angkor Wat and the chance to consult a mystical shaman known as Burnhard Yungkermann.

One morning we decided to head into the jungle to visit the old temple of Bang Milia. I was tasked with hiring a moped for Tony, but rather than use a hire company I opted to borrow a scooter from a man in a bar, using Tony’s passport as a deposit. The recklessness of this manoeuvre only became clear the following day when I went to return the scooter but couldn’t find the man with the passport.

“So what did he look like?” Tony asked as we drove around town.

“Well he was a South East Asian chap, quite short, and he was in that bar there - or was it that bar there?”

As I had already booked a flight from Bangkok, I had to get a bus out of Siem Riep that afternoon. Lovey needed to get to Thailand too, so the pair of us set off, leaving Tony clutching a stranger’s scooter, alone, documentless and without any way of leaving the country.

I wouldn’t see him again for five years.

World Cup 2006, Germany

Forward to 2006, and things seemed to be going well. I’d finished university in Brighton, got my basic journalist’s qualification, the NCTJ, and settled into a job on my hometown newspaper, The Surrey Herald.

That summer I arranged to go to Germany with a few friends to follow the World Cup. Mr Al told me that Lovey would be there.

“He’s going to pick us up from the airport,” Mr Al said.

Great. I’d met Lovey for a drink in London the year before, but hadn’t seen him properly for years.

***

I arrived at Munich Airport with Mr Al and my old friend Amit. Lovey met us there as arranged, looking healthy and casual in the sunshine. We hugged and made the usual noises as he led us to our transport.

“So what you driving?” I asked.

“A Trabant,” he smiled.

“A what?”

Lovey pointed at this impish, quirky little car with faded blue-grey paint. Tiny but perfectly proportioned, with big round headlights, little wheels and small windows. There was something comic about it - it looked a bit like a clown car - certainly not a vehicle to be taken seriously. I couldn’t help but laugh.

“What is that? Where did you get it?”

“It’s a Trabant. I bought it for $60 in Hungary.”

“It’s ridiculous.”

Lovey gave us a tour - the giant boot, the comically simple dashboard, the unique steering-column-mounted gear stick.

“It goes 80kph,” Lovey said proudly, to emphasise its crapness, “and look, there’s no fuel gauge on the dash. To find out how much gas you have, you pop the hood,” he opened the bonnet, “and dip this ruler into the gas tank.”

He did what he said and then held the ruler up in the sun, a thin high-tide mark rapidly evaporating on the surface.

“Four litres. We should be fine. But it’s a two-stroke, so when you fill it up, you need to add oil to the mix,” he waved a grubby little bottle of oil at me, “then you shake the whole car to mix it together.” He planted his hands on each wing of the car and shook it from side to side. It was so light it looked like he could lift it.

“We can lift it,” he said, laughing. “Wait until you meet OJ. Together we can lift up the back of it and shift it sideways. It helps with parking. It’s made of plastic that’s why it’s so light.”

“What?”

“Plastic,” he tapped the panel, “it’s made of plastic.”

We were all laughing now. So it was half-car, half-lunchbox? No, it probably didn’t even qualify as a car - it had a 600cc engine, just 25bhp. So it was half-lawnmower, half-Tupperware? Ridiculous.

Lovey explained that the Trabant was the East German competitor to the West German Volkswagen. In the 1950s, when it had been designed, there was a steel shortage in the Soviet Union. So the boffins had to find a replacement material to build the panelling for the car. They used Duroplast, a mixture of polymer resin and leftover waste from the Soviet Union’s cotton industry. The Trabant was the first car to be made out of recycled materials, possibly its only redeeming feature.

A small crowd of people had formed nearby to admire the car, which had a cult following in Germany. Some of the tourists were taking photos. We squeezed inside; it was cramped for four tall lads with tents and bags. In the front, my shins were bashing against a shelf that ran under the dash. In the back, Amit and Mr Al had their knees around their ears. We pulled away to the heavy revving of the little engine, basking in the laughter of bystanders. I loved it.

***

We spent the next week driving around in that thing. The Yanks had painted go-faster-stripes along the top and at our campsite, Brady, another American travelling with Lovey, knocked up a symbol, which he sprayed onto the doors. In the motif were the initials “MTP” - Mighty Tony Perez - a dedication to Tony, who was meant to be with us but had broken his ankle coming off a scooter in Cambodia earlier in the year and had to go home.

With Lovey and Brady was another Yank, John Bradford Drury, who knew Lovey and Tony from Washington DC and had been travelling with them. He had been dubbed OJ, or “Other John”, being the second John on their trip. OJ was a giant of a man, a huge, towering, six-foot-three figure with bulging, twitching pectorals and a square jaw. His physique was almost ogre-ish, his muscles had muscles on them, but beneath that powerful exterior was a soft centre: he worked out, moisturised extensively and liked cooking.

I didn’t spend too much time with OJ in Germany. My only real memory of him was one night, sitting around drinking with the group, seeing him alone by the campfire drumming furiously against his thigh with a pair of sticks.

“That’s one weird kid,” Lovey said, looking over. I would get to find out.

After a week in Germany we waved goodbye to Lovey, OJ and Brady and headed home. I occasionally thought of Lovey’s little Trabbi, remembering the night we squeezed six large men in and drove around for an hour, lost in Munich. Or when we had to quickly empty the boot of counterfeit Thai football shirts because we thought we were going to be raided by German police.

Lovey and OJ carried on in the tiny car, eventually nursing it to the palace at Versailles, on the outskirts of Paris, before it broke irreparably and had to be abandoned. They managed six countries in that Trabbi, attracting attention, infamy and laughter everywhere they went, and sowing the seeds for what was to come.

Europe To Cambodia By Trabant

I remember getting the email. The title alone was enough to get me going and although the content was vague, it was enticing: “The route has yet to be chosen, but it would certainly involve parts of Central and Eastern Europe as well as parts of Central Asia, Mongolia and China. The question mark is whether to take the northern route through Ukraine and Russia or the southern route through Turkey, the Caspian Sea and other countries in Central Asia.

“I have written to the nine of you because I know you all to have the travelling spirit and the desire to do something different. I have travelled with most of you at one point or another and think for the most part each of you know one another, or at least one other person so it would not be completely random. This could be a great opportunity to get away from the hordes and see something we are not pushed to see, that the Lonely Planet hasn’t put on the agenda for us.”

The idea instantly resonated with me and I was excited. I had just turned 24, and forty years of work stretched out in front of me. Surely it was the time for an adventure, when I had no mortgage, no wife or kids, no unleavable job? I had been working hard for a few years, why not take a break?

And I was especially keen to get off the beaten track. When backpacking I’d come to the conclusion that guidebooks, instead of opening places up for exploration, set artificial limits on your experience. People tend to follow the recommendations and stick to the guide, resulting in hundreds of people following the same, weary paths. But this way we would be off the map. I didn’t know of any guidebooks designed for people driving plastic Soviet relics across Eurasia.

I tempered my excitement with the thought that it might be an idea that sounds good at the time, but slowly drifts into nothingness. So I resolved to keep things under my hat - the whole thing could easily fall flat in the next few weeks.

But instead of drifting away, the idea developed, snowballed and gathered momentum as the emails kept coming. Should it be a race, or should the cars support each other? Do we need a theme? Maybe we should do it for charity? Should we stick to Soviet countries? Maybe we should film the whole thing?

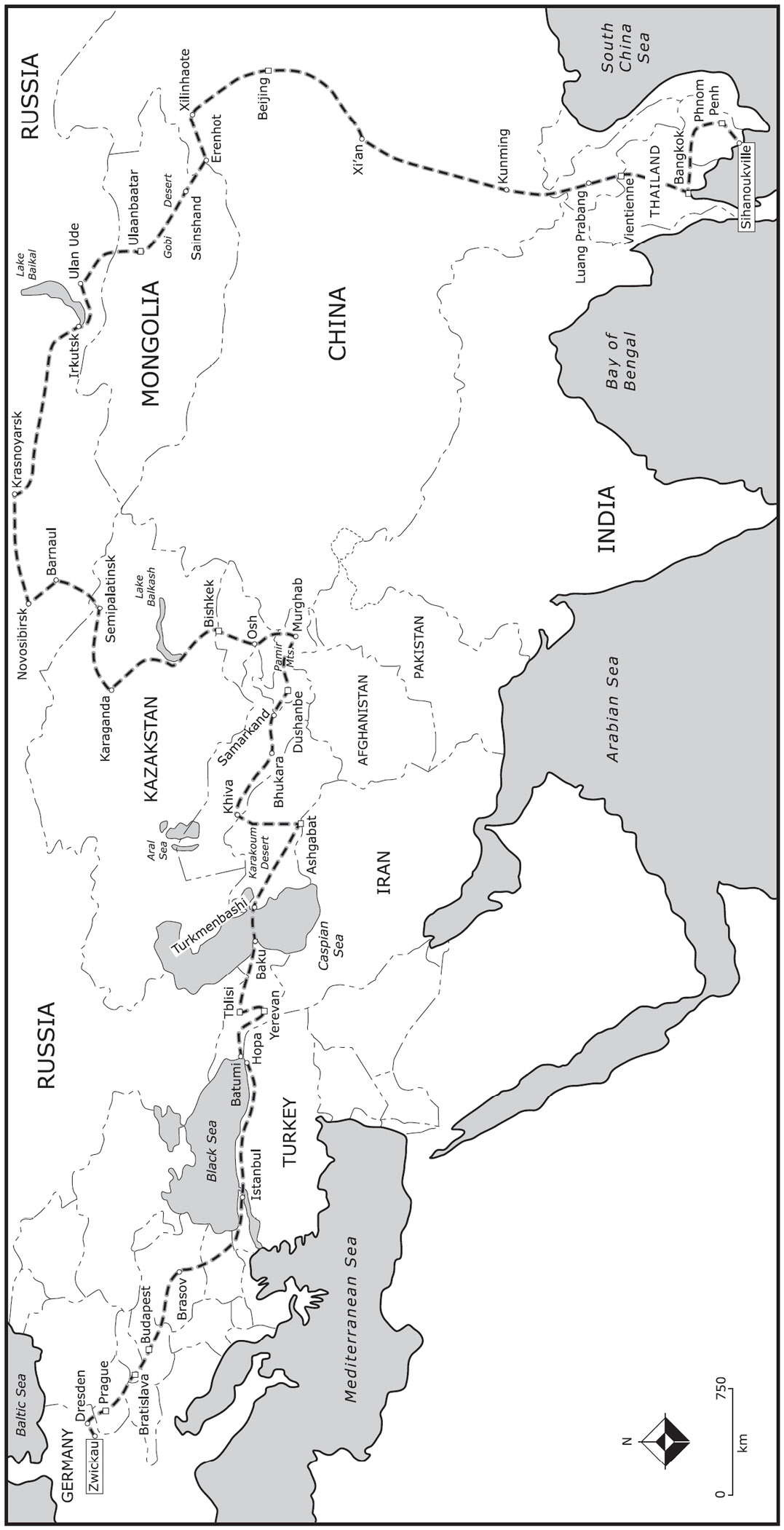

As the plan morphed and developed it crystallised. The Trabants would be driven from the site of the old Trabant factory in Zwickau, Germany, to the home of the charities the group would be raising money for, in Phnom Penh and Sihanoukville, Cambodia.

Tony and Lovey worked out a route and chose not to go the quickest, straightest or easiest way. Instead they picked out things they wanted to see and places they wanted to go. They would take Trabbis where they had never been before: the Pamir Mountains, the Gobi desert, the Asian jungle.

The cars would go from Germany, south and east through the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria, full of Trabbi enthusiasts and easy repairs, then east through Turkey and the gateway to Asia. From there, north into the Caucasus, crossing Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan before getting a boat across the Caspian Sea into the forgotten world of Central Asia - the police state of Turkmenistan, the beautiful Silk Road cities of Uzbekistan, the stunning mountain passes of Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, and the endless flat of the Kazakh steppe. We would cross the forests of Russian Siberia and Mongolia’s icy plains, then plough south through booming China before hitting the sun-speckled hills of Laos, the welcoming familiarity of Thailand and the jungles of Cambodia.

It would be a 15,000-mile journey through twenty-one countries. They reckoned it would take four months. The trip would be entirely self-funded, the trekkers paying for everything needed to get to across Eurasia. But they would also try to attract sponsorship to raise money for two Cambodian charities dedicated to supporting and educating children living in poverty, Mith Samlanh in Phnom Penh and M’Lop Tapang in Sihanoukville. And it would be filmed, at the very least for posterity, but hopefully we would get a TV network interested in the footage. We needed a website, press coverage, PR stunts, fliers, posters, a media presence, sponsorship, celebrity endorsement, T-shirts, bumper stickers and business cards. Lovey was nothing if not ambitious. He wanted this to be huge.

He called it Trabant Trek.

The Waverer

There were a lot of names on the list of people who were interested. Lovey was never able to tell me how many people he invited, but Tony guessed at about thirty or forty. There was plenty of correspondence between people who were committed in varying degrees and over the next few months the faint-hearted drifted away or pulled out altogether as further arrangements were made and realities dawned.

Lovey was the instigator and the driving force. He’d constantly be sending out fresh thoughts, guiding the development and explaining new opportunities and pitfalls that he’d come across. Sometimes we would get two or three emails a day from him and I admit to dreading opening my inbox for fear of what new horizon had been opened up.

I was sold on the idea of Trabant Trek, but wasn’t sure if it was the right time for me. People were talking about leaving in May or June of the next year, 2007. At that point I would only be 15 or 16 months into my two-year training contract at The Surrey Herald. If I left then, it would be without my senior qualification, and would mean my time at the newspaper was wasted.

But as the New Year turned, fate intervened. Rumours were flying around that my paper was going to be bought out. This led to speculation that trainees like myself wouldn’t be able to finish their course. So I took this to my editor and asked if I could take my exams in May, six months early. After some discussion, he agreed.

I got in touch with Lovey and told him I was in.

***

There was plenty to be done. Ironing out the minutiae of the route, working out what permissions were necessary in which countries, what visas and car papers would be needed, preparing different pitches for potential sponsors and TV companies.

In all honesty I didn’t really do any of this stuff. I sent my passport with a load of visa forms out to DC, where the Americans got them all done together. I sent some money out to help cover start-up costs, and wrote and sent out press releases and sponsorship letters for the UK, with little response.

It was a pitifully poor contribution compared to what Lovey and Tony were putting in, and I felt bad. Often Lovey would send out a long, rambling group email setting out just how much needed to be done, and just how much of it he was doing. This always made me feel guilty. “I think the rest of the group took for granted just how much work Lovey and I put into planning this thing,” Tony said, many months later.

I told myself I had other things on my plate - a full-time job, preparing for exams and gigging with my band Goldroom. Talk of special highway passes to cross the Pamir Mountains in Tajikistan seemed a little removed. It’s hard to get home after a full day and set about chasing sponsors and media. That’s what I told myself, but Lovey and Tony seemed to have no trouble.

Trabant Treffen

By June 2007 I had passed my exams and handed in my notice. The initial plan was for the Trek to set off from the annual Trabant festival in Zwickau, the Trabant Treffen. But as the June date neared, and the to-do-list built up, Lovey decided to push everything back a month.

But we still wanted to go to the Treffen to spread the word about the Trek, as there would be tens of thousands of Trabbi enthusiasts there, and maybe some of them would sponsor us. I agreed to head to Germany with the only other Brit, a pretty blonde called Samantha or Sam, whom Lovey had met on his travels. Lovey flew from DC to Budapest to pick up the Trabbi that had already been bought. There he met up with our Spanish trekker and the pair drove to Germany to collect Sam and me.

We got the tent up just as the heavens opened in a storm straight out of a Hammer horror film. Forked tongues sliced through the sky, echoed by the steady murmur of rolling thunder. A small sea rained onto the campsite, turning everything to muck. We’d cleverly camped in the bed of a natural gully and as the field saturated a stream formed and began to flow through the tent, washing grass, litter and insects into our new home.

We used beer crates as stools and sat close together, wet and shivering but happy in the gloom. In those cold, damp and close quarters I got to know Carlos Gey, the Spaniard. His surname really was Gey, though he pronounced it “Hay”, which always amused me. Often I just called him “The Gay” or “The Losbian” or “The Spaniard” or, occasionally, “Pedro”, though I don’t think he really liked any of those names.

The oldest of our group, Carlos was a Catalan and had been working in a hostel in Barcelona before we met, though really he was a marine biologist who had spent two years in Alaska counting fish. I never understood that.

Carlos had a perfect grasp of English, which he liked to demonstrate through the use of terrible puns, the sort of bottom scrapers that down-market tabloids would shy away from. These always made Lovey crack up. I never understood that either.

Shorter than me, but taller than Tony, Carlos was tanned and dark, with thick-rimmed glasses. The glasses disguised his most powerful weapon, the eyes. Oh the eyes, the glaring gateway to his Id, capable of firing fiery Exocets of foreboding at friend or foe. The “Spanish Eyes”, as they were quickly dubbed, the brooding, faux sexual look he pulled for cameras (and women), the dark, angry Latino stare he used to show displeasure. It made everyone laugh: “Don’t do the eyes at me. Not the Spanish Eyes. He’s doing the eyes. Someone stop him doing the eyes.”

Despite his smaller stature and girl’s hips he walked a lot faster than me, often with his hands clasped firmly behind his back like Inspector Clouseau. I prefer to saunter around new places, slowly breathing it all in. But once Carlos has chosen his destination he puts his head down and gets there. Often that was exactly what we needed.

“Carlos gets things done,” OJ once said, quite correctly.

The festival was a mud bath, but we made the most of it. Every conceivable Trabant modification was on show, like peacocks flashing their plumage. Stretch Trabbis, jeep Trabbis, lowered Trabbis set on alloys with tinted windows and chrome rims. Some had one-litre engines, some had no engines, others had tents on their roofs, one was turned into a trike, another into a boat, one Trabbi was mounted on a 4x4 chassis, most had four wheels, a few had six wheels. My personal favourite had a garden table and benches mounted on its roof. Six large German men sat atop the moving vehicle spilling frothy lager onto passers-by and jeering in Teutonic unison.

***

A week later I got a phone call from Sam. She was pulling out. Her weekend at the Treffen had been characterised by running arguments with Lovey. She was an accountant by profession and had an orderly mind. But Lovey was light on facts and specifics, as we all were, and it is fair to say that the two didn’t combine well. She expressed the fall-out a little differently and entirely unprintably.

So we were a man - or a lady - down. Sam was the third female to pull out and there was a danger that the Trek was going to become a little cock heavy. We were down to five guys and two girls, though Lovey was still working on a few people, and there was a chance that some folk would travel with us for a few weeks here and there. No official departure date was set, but the call came in to assemble in Budapest in the second week of July. The Hungarian capital would be our base camp. The Trabants were there, and Lovey knew a Trabbi specialist who would be making modifications to the cars and sourcing spare parts.

There was a lot to be done, I was told; we needed to assemble and start doing it. Once everything had been organised we would drive to Germany for the official start of Trabant Trek.

***

Setting off on that sort of journey always gives me butterflies. That feeling of nerves and expectation in the pit of your stomach - who knows what will happen next? There were new people to meet, new friendships to form, and a car to be driven across Eurasia. How do you really prepare yourself for that? I guess you can’t. You just go ahead and do it.

Four months, it’ll take four months. Over by mid-November? I told my friends and family I would be home for Christmas, just to be on the safe side.

On 9 July 2007 I flew out of England.

Trabant Trek Headquarters

Carlos and Megan met me at Budapest airport. I hugged the little Spaniard, who was sporting a new Trabant Trek T-shirt for the occasion, and gave Megan a peck on the cheek. I only knew a little about her, and I’m not sure what I expected, but she wasn’t it.

American and about my age, she was blond, unmade-up, casually dressed and, like Lovey, had spent some time growing up on US military bases. Maybe I had imagined more of a straight-laced, all-American do-gooder, which she certainly wasn’t, and I mean that in a good way. Opinionated, forthright, hands-on, emotional, tough and no shrinking violet, she said what she thought and never hesitated to denounce a plan that she saw as flawed, a trait which occasionally provoked other members of the team. She had a great sense of humour and a natural instinct for physical theatre, often annotating her stories with actions, strange songs and dances. She could throw a tantrum at a border guard in the blink of an eye, and return to normal in a few breaths. But that was all ahead of us.

The pair had come to collect me in one of the Trabbis, the same one Carlos and Lovey had driven to Zwickau for the festival the month before. In the short time that it had been sitting in the car park it had somehow managed to discharge its battery. So, appropriately, my first job on the Trek was to flag someone down and ask for a jump-start. This was a role I would become accustomed to.

I was taken back to the home of the delightful Angyal sisters, Zoe and Melody. They were friends of Lovey, who once worked in Budapest, and ever since opening their door to Carlos a month before they’d had played host to a Trabbi invasion.

“So how many other people are coming? It would be nice to know when someone else is going to be staying here,” Melody said, to no one in particular, by way of a welcome. Tony gave me a hug, asking “What’s up, Danno?” which was a relief as he had every right to thump me for leaving him passport-less in Cambodia five years before.

Also at the house was our Hungarian trekker, Zsofi Somlai. Pretty, well-kept and brunette, she’d spent a year in the States so spoke faultless American. At 21, she was the youngest of the group, and had never travelled for more than a few weeks before, but you wouldn’t have guessed it from her confidence and organisation in those early Budapest days. It was her home town, she was a part-time tour guide and always seemed to know what was going on. Zsofi was still studying at the time, but was so enamoured by the trip she was ready to take four months off. She told me that her friends and family thought she was crazy to be heading across the world in Trabants with virtual strangers. And when put like that, I guess she was. But she could be determined and single-minded and had her heart set on the Trek.

Over the next few days we gradually turned the place into Trabant Trek Headquarters, known locally as TTHQ. Boys were stationed downstairs in the dungeon, an unfinished apartment with the grimy ambience of a squat party. We slept on mattresses pushed together on the floor between various pieces of upended furniture.

The ladies were nesting in the loft, normally used as a storeroom. They bedded down among dusty vases, dodgy TVs and old rollerblades.

From that luxurious base we plotted global dominance, assembling resources and contacts ahead of our departure, scheduled for 17 July - or the 18th or perhaps the 19th. Nobody was really sure, the dates kept shifting and swirling. Do you need any sense of organisation to travel the world? I was soon to find out.

Picking Up The Rest Of The Fleet

We woke up at Zsofi’s apartment in the centre of Budapest. Megan, Tony, Carlos, Zsofi and I were a little the worse for wear after an exuberant evening, but we immediately dared the midday sun to pick up the last two Trabbis and the Mercedes that would act as our support vehicle. All of the cars had been bought and modified by Gabor, a Trabant specialist who ran a garage in the city. He wasn’t around, but said we could go and collect them from outside his place. Despite our physical condition, we were all excited to get a look at the cars we’d be spending the rest of the year in.

On arrival things seemed bad. The lock was jammed on one Trabbi, so Carlos had to break in through the boot. He smashed off the parcel shelf and slid his scrawny Spanish butt over the backseat, only to find the little tyke had a flat battery.

There was no trouble getting into the other Trabbi, although it too had a dead battery, and once we jump-started it and tried to drive off we found the rear wheel had completely seized and we could only drag it along the road.

There was a brief interlude where it seemed things had truly fallen apart. Dehydrated and sweating in the heat, we cursed and considered the possibility that Trabant Trek might amount to little more than a four-foot skid mark made by that jammed rear tyre. Apparently a man known only as The Bear had been working on the cars with Gabor. Zsofi got in touch with him and he claimed the wheel seizure was no big deal - the car had just been sitting still too long.

“These are Trabants, these things happen,” was the gist of the phone call.

We had little choice but to leave the seized Trabbi for The Bear.

In his younger days Tony had spent a couple of years training to be a mechanic. Although he now managed a bar and restaurant, this qualified him as the official team mechanic, a vital role if we were to coax the old cars across two continents.

“Well we’ve got the worst cars in the world, so it only seems right that we have the worst mechanic in the world,” Tony told me comfortingly.

On further inspection by The Mighty Tony P, the prognosis was raised to “good”. It seemed the Merc had a fairly new engine, and new wiring, and the Trabbi ran fine. Tony fixed the broken door and later that night we found a couple of headrests in a pile of discarded junk.

“This car will get us to Cambodia, I have no doubt” was Tony’s analysis as he stooped over the engine. Time would tell.

***

The year 2007 was the fiftieth anniversary of the first Trabant, the P50. Plenty of newspapers ran features on the car, with fond accolades such as “the rattle-trap cars that have become perhaps the most enduring symbols of the former East Germany” (New York Times) and my personal favourite, the headline from The Times (London): “Party time as world’s worst car celebrates 50th birthday.” The story went on to describe the Trabant as “the smoke-spewing communist car whose coughing two-stroke engine has been compared to a death rattle.”

We’ll take three.

All of our Trabbis were from the 1980s. One was a Kombi model from 1987 with a big boot, like an estate car. The others were limousine-style 601 models, from 1985 and 1986. Although the cars were only twenty years old, the design was exactly the same as the original 1963 model. Very little had been changed or added over the years, and so, although the parts weren’t frighteningly old, the design and technology were. The engines were simple things - air-cooled, two-cylinder, two-strokes - which, we reasoned, was good because there wasn’t too much to go wrong, and they weren’t too difficult to fix.

But spare parts would be pretty much unattainable once we were out of Eastern Europe. This was where the Mercedes support vehicle came in; it was a big old station wagon with a huge boot and a hydraulic suspension. We planned to fill the thing with enough spares for three cars for four months on the road - we pretty much wanted to take an entire spare Trabant in the back of it. A spare engine, spare gearboxes, clutch plates, A-arms, transaxles, carburettors, bulbs, engine mounts, fan belts, spark plugs, exhausts, batteries, bearings and anything else that could go wrong. The larger, more powerful Mercedes would bear the brunt of this extra weight.

We also needed to take enough two-stroke oil with us for all three Trabbis for the entire trip, as we weren’t sure whether it would be available on the road.

Lovey and Tony calculated that to be about 120 litres. So we had two giant barrels of oil along for the ride too. We were able to fit these in the Kombi by removing its rear seats, and to save more space in the Trabbis Tony bolted spare wheels onto the car’s wings, giving them a rugged, rally look.

To prepare them for the terrain ahead, Gabor made a few alterations to the Trabants. He reinforced the leaf springs that acted as suspension, and made thick, removable metal plates that bolted on under the Trabbis’ engines to protect them. The Trabbis themselves cost us between £150 and £350 each. The metal plates were £250 a piece.

The Mercedes was our biggest expense, tipping the scales at a hefty £1,500. But for that price we couldn’t find anything else with enough space in it to do the trick. Strange to think we could probably have bought a dozen Trabbis instead.

Although the Trabants could be taken up towards 100kph, Gabor said we should avoid it. If the cars were to make it, he said we should consider 80kph our maximum speed, and on bumpier, rougher roads, we should take that right down to 30 or 40kph.

This was difficult, especially early on, when we were on decent European roads. Sticking to 80kph on the German autobahn, where there is no speed limit and BMWs doing 160kph overtake you, is a challenge. But then, when it takes 21 seconds to get from 0-95kph you are pretty much resigned to going at a gentle pace.

An unspoken decision was made to do everything in kilometres, and most of the speeds and distances in this book reflect that. Only the Brits and Americans really use miles, most of the distances on road signs across the world are in kilometres, as were the Trabants’ speedometers and odometers. So we got into it, and it became second nature to only think of things in kilometres. And besides 70kph sounds quicker than 50mph, and managing 450 kilometres in a day sounds better than 280 miles. (In case you’re struggling, there is 1.6km to a mile.)

That night it was Tony’s birthday, 23 he claimed, though that statistic didn’t bear close scrutiny. We went to Zsofi’s folks’ house for a party. I think her parents were keen to check out what type of hoodlums were taking their daughter away. I made a fool of myself during a brief altercation with a mosquito net, but other than that we came through the event unscathed.

***

OJ arrived the next day. The more I got to know him the more I liked him. He’d initially seemed a little aloof, but over the next few weeks that fell away and I grew a genuine respect and affection for the Oj. Sometimes we called him by his middle name, Bradford, and often we called him The Slav, as he claimed to have Slavic ancestry. Smart, educated and good-looking, he liked to cook and had a passion for languages, things we knew would help. He also had the Strength of a Thousand Men special ability, which would surely come in handy.

They were strange days. We were treading water really and the period was characterised by an utter lack of organisation. Megan set about trying to find hostels along the way that might put us up for free. Carlos looked for people who could do the same thing on websites like Sofa Surfers and Hospitality Club. Zsofi worked on sponsors and Tony tinkered with the cars while OJ learned Russian. It was swelteringly hot, and we all invested a lot of time in staying cool.

To the mix were added Justin Rome and Marlena Witczak. The pair were friends of Lovey and had been travelling around in Europe that summer so decided to come and meet us. Marlena was Polish, but had an American passport and was studying in Boston. She was great fun, always laughing and giggling and never taking things too seriously. She got on well with everyone, and formed a close friendship with Megan. We were all keen that she come along with us, and she wavered for a bit but eventually agreed to tag along, taking the place of Sam and bringing our numbers back up to eight - five chaps and three ladies. Four Americans, a Hungarian, a Spaniard, a Pole and a Brit. An eclectic mix of nationalities and near strangers.

Lovey arrived on 20 July, adding even more hair to the trip. Tony and Megan had already been in Budapest for a fortnight, I’d been there slightly less, and I guess we were hoping that Lovey would provide the answers and the impetus we needed to get things moving.

There were plenty of meetings and discussions, but they could go on for hours and we weren’t always pulling in the same direction. It was pretty much the antithesis of a military operation. Lovey was the best informed, but he had a penchant for drama. He rarely mentioned things, instead he announced them, and sometimes I felt uncomfortable getting involved in the decision-making, especially when I’d done none of the planning and wasn’t really up to speed on a lot of the details.

There was so much going on, things became what the Americans called a “cluster-fuck”. I was never sure of what that meant, but the term was bandied about aplenty and seemed to sum up the general vibe.

Trabant Trek was a cluster-fuck.

Dante, Fez And Ziggy

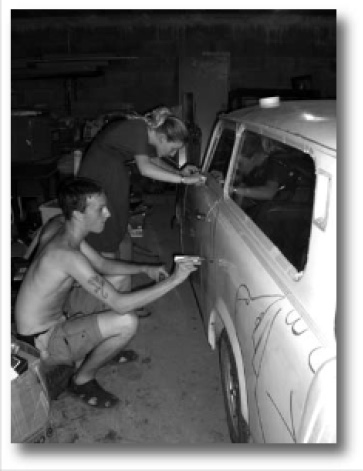

We always planned to paint the cars, and Montana Colours in Barcelona had kindly donated forty cans of spray. But none of us really knew how they worked. Luckily, living with us at the Angyal house was a graffiti artist named Johnny who agreed to bring his crew in and do the job. So Johnny and his mates, Nandi and Luca, showed us a few sketches, discussed a few designs and then went at the cars. We plied them with beer and they worked into the early hours on the street, listening to hip-hop and smoking.

The results were fantastic. Suddenly the cars, which had previously been dowdy, Soviet murky-grey or blue, were vibrant and alive. Three distinct designs, but clearly part of the same team.

One was a deep sky blue with a rising sun coming from the front wheel arches, its orange and yellow rays streaming down the side of the car. This was the same car that Carlos had taken to Zwickau and back, then driven around in Budapest for a month. He felt a real kinship with the thing and named it Fez.

The Kombi model was mostly black, with psychedelic, abstract, eye-like shapes swimming in a fiery finish. Tony took to it straight away. “I think it looks like little devils burning in hell,” he said, and named it Dante. Each to their own.

The last car had a clean, geometric design with plates of brown and cream colour divided by sharp, jagged bolts of gold. As the car in the best condition, Lovey had always had his eye on it. It was named Ziggy.

The Mercedes, which we didn’t bother painting and always looked rather clapped out, had a variety of names, mostly insulting, but Gunter and the Merkin seemed to stick. A merkin is a pubic wig.

Painting the cars was a seminal moment, it forged them into a unit and with their names each seemed to develop a distinct personality. Fez was unreliable and childish but fun, normally inhabited by Megan and Marlena. Dante was slow and heavy and constant, carrying Zsofi and Tony and his assorted tools. Ziggy was quick and messy and always keen to lead the way, particularly with Lovey behind the wheel. Gunter was a disaster on wheels and driven in a rota, except by Zsofi, who refused to go near it. All four of the cars were a little sporadic. There were plenty of dead batteries and jump-starts and getting into one was always a bit of a lottery. But we were getting to know them and it was all good preparation for the months ahead.

Z-Plates

The next day we got a new recruit. The TV deal that Lovey had been working on came to fruition and the production company sent a cameraman to join us. His name was Istvan, he was Hungarian and he spoke next to no English. Quite how they thought he would cope was beyond me, but from day one it seemed like it was going to be hard work. We re-christened the poor bloke Melvin and tried to work around him. We were also lent three mini cams to use in the cars for our own personal filming.

There was still a long list of things to do, but time was bearing down on us. We had already received a lot of our visas, so we had set dates to be in certain countries, and needed to head off soon. Unfortunately we made the mistake of putting export plates, or Z-plates, on Dante, Ziggy and the Mercedes. This allowed us to take them out of Hungary and not bring them back again. But it was a one-way deal - once the cars had left the country, they could not return - and seeing as we were planning to drive to Germany for the official start of the Trek, then head through Hungary on the way back, this was a problem.

After a lot of debate we realised there was nothing we could do, it was just a cock-up. So only one Trabbi, Fez, could make the journey to Germany for the start of the Trek. Lovey, Tony and Zsofi wanted to stay behind to finish various jobs. So Carlos, OJ, Justin, Istvan, Megan, Marlena and I would go to Germany in Fez and Istvan’s car.

***

The group was gelling well. A few people had bickered with Megan over her occasional negativity, I had attracted some flak for overindulging in the vino, and Lovey’s attitude of infallibility had drawn the odd murmur of discontent. But, although I can’t speak for everyone, I thought it was a good bunch. Lovey had chosen well.

We didn’t pack the cars properly when setting off. We knew we’d be back at TTHQ in a week so we just threw in overnight bags. It would be a little excursion ahead of the big event, a dummy run to iron out the issues, and the first real test for Trabant Trek.