Central Asia

Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan

31 August – 13 September 2007

Q) How do you double the value of a Trabant?

A) Fill up the tank.

Turkmenistan

Reaching Central Asia felt like a major achievement for the Trek and at the same time the beginning of a new challenge. Europe and Turkey had been perfect places to cut our teeth, with good roads and facilities, even though we’d made things as hard as possible by rigidly repeating our mistakes.

The Caucasus was more difficult, there was a marked reduction in the quality of the infrastructure, but to me it still felt pretty European and accessible. But Central Asia was a major step into the unknown, not the sort of place you normally go on your summer holidays. And that was exciting.

These were a different people from the Caucasians we’d left behind, and a different landscape from the rolling greens of Azerbaijan. This was a place of deserts, mountains and nomads that we knew as “the stans” - Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan. Names that hardly roll off the tongue or get much attention back home in Blighty, and before the trip I would have struggled to place any of them on a map. But this was our chance to explore.

Over the last few millennia Central Asia has been overrun by pretty much whoever was dominant in the region - Parthians, Macedonians, Huns, Scythians, Mongols, Seljuk Turks and Ottomans all marched through. The region’s heyday coincided with the rise of the medieval Silk Road when local kings and khans used their military power to control the trade that crossed to and fro between the Mediterranean and China. But these routes dried up when Europeans discovered a sea route around Africa, and trading power shifted to the seafaring nations - the Portuguese, Dutch and British.

Since the late nineteenth century Central Asia had been consumed and hidden by the Russian Bear, a thick cloak thrown over the region so that the West had almost forgotten the centre of its own map.

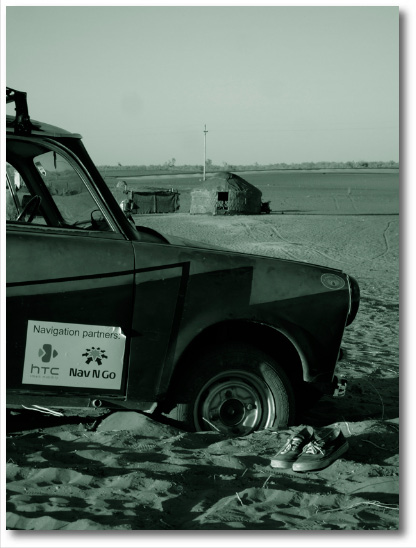

Ziggy and a yurt in Uzbekistan

Turkmenistan, possibly the most secretive and isolated of all the Central Asian countries, was our first stop and nobody really knew what to expect. It sits on the east coast of the Caspian Sea and is divided from Iran to the south by the Kopet Dag Mountains, Kazakhstan to the north by Uzbekistan, and it is almost entirely desert. But other than those scraps of geography all we had really heard was a steady stream of rumours and urban myths about the eccentricities of the former president, Saparmurat Niyazov Turkmenbashi.

Turkmenbashi was the sort of priceless lunatic that only extremist ideologies seem able to turn up. A true Soviet relic, the man made David Ike look like a Cartesian realist and creationism seem the result of rational enquiry. He existed on an entirely different plain of consciousness.

Turkmenistan was the only Soviet satellite that didn’t want independence when the Union collapsed in 1991. Moscow gave the country no choice so Turkmenbashi, then just the humble communist party leader Saparmurat Atayevich Niyazov, waited until a load of Aeroflot planes were refuelling at Ashgabat airport and then declared Turkmenistan a free nation, gaining independence, ultimate power and the country’s first and only airline.

After winning 98 per cent of the vote in the country’s first “democratic elections” he managed to keep Turkmenistan from collapsing into civil war and lawlessness while its Central Asian neighbours did just that. He declared international neutrality, billing the country as the Switzerland of Asia, and set about harvesting the nation’s vast gas deposits.

Alongside these laudable achievements he ruthlessly clamped down on political opposition and fostered one of the more bizarre personality cults in the modern world, setting himself up as a semi-deity and taking the title Turkmenbashi, “Father of All Turkmen”. He renamed some of the days and months after friends and family, he made his book Ruhnama (The Book of the Soul) part of the curriculum, and forced learner drivers and students to pass exams on it. He banned beards and gold teeth, pop stars from lip-synching and newsreaders from wearing make-up. But not everyone’s perfect.

The old mentalist died a year before we arrived, and some of his more eccentric decisions had been reversed, but his legend and the deliberate veil of secrecy around the country added to the intrigue and expectancy.

***

In order to gain permission to cross Turkmenistan with nine people and four cars, we had agreed to be escorted by a properly licensed guide. He was expected to ride with us, so for a while we’d be up to ten, our maximum capacity, and I was interested to see how he would cope with the rigours of trekking: the breakdowns, the late nights, the wrong turns, the backtracking, the committee meetings, the farcical sense of organisation - and Tony’s feet.

In fact, he had a pretty good introduction to life on the Trek. We’d arranged to meet him straight off the boat at the Caspian Sea port of Turkmenbashi (the former-President even took to naming cities after his self-appointed title). We were fully one week late, and the poor chap had been waiting there the whole time. At least he now knew what to expect.

The guards at the border wore thick safari suits despite the heat and looked Chinese - broad Mongol faces, thick black hair, slanted eyes and a chestnut complexion. But our guide, Ilya, looked like a Belgian professor, with mousy blonde hair, milky skin and light blue eyes.

“Do you like camels?” a young looking border guard asked me.

“Um… not really.”

I’d spent three uncomfortable days on the back of one in the Sahara a few years back. They bite, they sneeze, their ungainly gait and ridiculous shape make them a terrible ride.

“They have good milk. You must try it.”

It hadn’t occurred to me to taste their milk.

Processing us at customs took hours, our first introduction to the Turkmen bureaucratic machine that we would get to know well, but it was a relief just to be off the damn boat. We were charged $60 per car as a tax on petrol, something that we argued vehemently against. But we were placated the second we got to the pumps. The government-subsidised petrol in Turkmenistan was cheap. To fill up all three Trabbis, a total of 75 litres, cost $1.50. The attendant also demanded $1.50 to work the pump, but no one argued.

Ashgabat

From Turkmenbashi we drove through the night to reach the capital, Ashgabat, City of Love. The famously barren Karakoum Desert makes up about eighty per cent of Turkmenistan, and the roads through it are long, straight and sleep inducing. The wind had swept the sand into tidy, rippling piles that stretched to the horizon and swathes of salt lay crystallised in the troughs like pockets of snow. We drove through a village of one-storey buildings, where cows and camels strolled vacantly down the streets or stretched out in the shade and scratched their backs on fencing.

“The Great Silk Road”, a sign announced somewhat hopefully from among the peeling, crumbling low rises and dusty, wooden shops. Nearby, women squatted by huge pans over open fires along the road.

I knew that Turkmenistan was considered a police state, and although I had a rough idea of what that meant, I’d never been to one and couldn’t be sure exactly how it worked. I soon learned that there is little clever about the name, but that it’s pretty self-explanatory: it means there are police everywhere. Every hour on that long drive to the capital we would pass another checkpoint. It was a lottery whether they stopped us or not, but if they did, Ilya would jump out and show our papers.

“Thanks for not asking for money,” Megan shouted at one group as we left, still smarting from the constant “taxes” we had been paying in Azerbaijan. As the early hours floated by I fell asleep in the back of Fez, and when I woke we were at a large, grand hotel in the city. Everyone was raving about the drive into Ashgabat and I was gutted to miss it, but my room had a bathtub, probably my favourite place to unwind. There were no plugs, something I have learned is a feature of former Soviet states, so I blocked up the hole with tissue wrapped in plastic from a bin liner and relaxed in the hot water. A welcome introduction to the capital - this place isn’t so bad after all.

***

“So what do you think of Turkmenbashi?”

I was breakfasting at the hotel, which we were sharing with a group of forty cyclists who were riding from Istanbul to Beijing.

The waitress smiled sweetly, “He was a great leader.”

“There are those who say he was a deranged megalomaniac.”

Anger flickered across her face: “He was a great leader.”

She cleared my breakfast and hurried off.

“Careful there, mate,” came an Australian voice from the next table. He was leathered, tattooed and drinking vodka. It can’t have been later than 10am. “You don’t want to get anyone into trouble. The whole place is bugged. All the hotel rooms, the restaurants, anywhere foreigners go.”

It could be true. Turkmenbashi was famously suspicious, so much so that we were warned not to film or photograph except at certain tourist sites. I shared a vodka with the Aussie while someone did a cash run, and suddenly we were all millionaires - I got a thick wad of 1.13 million manat for my $50 bill.

***

“It reminds me of Vegas,” Megan said as we drove through the Legoland streets of central Ashgabat, “everything here looks like it was meant to.”

I could see her point. It was all well-manicured, perfectly polished, neat and tidy. But nothing in Vegas struck me as pretty and I felt the same sanitised sickness in Ashgabat. It didn’t appear real, not grown organically as the city had developed, but built very deliberately by a man with a strange marble vision. The stunning high-rise office blocks and apartments stood in complete contrast to the rest of the country. It looked as if a demented utopian with a curious lust for marble was left in charge of city planning and accidentally blew the national budget. Which is almost exactly what happened. On close inspection I saw many of the buildings were virtually empty - sterile phallic monuments to one man’s industrial delusions. The giant architecture was out of place and preposterous, deliberate ostentation in a country that looked like it had bigger problems to deal with.

Walking through an Ashgabat bazaar, it was easy to forget where I was. There was such variation in the people it was like strolling through Turkmenistan’s history. Alexander the Great offered me Half the Known World by the Age of 32; there was Genghis Khan in Rape ‘n’ Pillage, first left after Timurlane’s Mass Murder Emporium; Catherine the Great was on the vodka stand and security provided by one Joseph Stalin.

With predecessors like that, it’s no wonder old Turkmenbashi was a little extreme.

I asked Ilya why everyone looked so different and he gave me an answer tinged with Soviet schooling: “During Soviet times there were fifteen republics and you could travel freely between any of them, so people from the whole of the Union came here. My grandparents came from Russia after the earth- quake.”

The earthquake happened in 1948. A nine or ten on the Richter scale, it flattened Ashgabat in a second, killing 110,000. In typical Soviet fashion Stalin claimed just 5,000 had died and sealed off the area for five years so the city could be rebuilt.

“After that seventy per cent of people in Ashgabat were Russian. Now it is two per cent. Most of them went back to Russia in the ’90s,” Ilya added, looking wistful, “I would like to go to Russia too one day.”

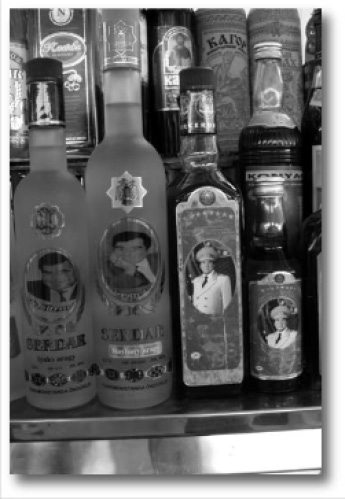

The young Turkmenbashi survived the earthquake, though his whole family didn’t, and sixty years later I could see his image all over the rebuilt city. There were gold statues and busts of him along main roads, he was on factory buildings, bank notes and vodka bottles, in hotel lobbies and police stations, even in people’s homes. The country’s slogan, Halk, Watan Turkmenbashi - people, nation Turkmenbashi - was painted all over the place.

I saw his Ruhnama on shelves in most official buildings. I hadn’t read it myself, but I understood the book was an attempt to invent a history for Turkmenistan. That was the biggest challenge facing Turkmenbashi, trying to create a culture and heritage for his people. To forge a nation, you need a sense of a shared past, some heroes to celebrate, some victories to unite, a sense of commonality. In that respect Turkmenbashi did a good job of holding the country together and keeping it away from the Iranian extremism just over the border. Admittedly he set himself up as a semi-deity, but most leaders tend to have a bit of ego.

Drinking to the personality cult in Turkmenistan

I asked Ilya what he thought: “Niyazov? We loved him. The people here were hungry so they needed a leader. Someone to help them. He did a lot for us. You can enjoy yourself, you can have fun, you can pick up women. But if you have politics, then it’s a problem. Otherwise - no problem.”

I wondered how the people would remember him. Would there be a Khrushchev-style denunciation of the cult of personality? Looking around the place I doubted it. Already I could see the posters of his successor, the neatly named Gurbanguly Berdimuhammedov, hanging on public buildings. Out with one cult, in with another.

Battle Lines

Initially we hadn’t really divided up the cars, thinking anyone could drive any car they fancied. But at a petrol station in Ashgabat I had a row with Lovey that would cement divisions.

The issue was Fez. There was a bit of stigma attached to the little car. It was clearly breaking down the most, the problems had been there since Budapest, but as Megan and Marlena were driving it they were attracting some blame. Someone branded them “The Muppets”, which they found offensive and it created a bit of an us and them mentality. Previously I had flitted between Fez and Ziggy. But since Brady arrived in Baku he had been in Ziggy and I had been riding in Fez and now I was getting some of the flak.

So I asked Lovey if I could drive Ziggy. He said no I couldn’t because I was “careless”. I asked what he meant, and he said I’d slept on the handle that lowers the passenger seat and bent it. He also mentioned an occasion when I had scraped the gears, then claimed the problems with Fez were due to such carelessness.

I disagreed and pointed out that Fez had been driven the most – from Budapest to Germany and back twice - while the other cars were stationary, and Carlos drove it around Budapest for a month before we even set off. As Tony had agreed, it was natural that there was more wear and tear. But Lovey made it clear it was the fault of Megan, Marlena and me: “It’s carelessness. You’re just careless with it.”

I should have pointed out that carelessness is losing your wallet, credit card, camera and $300 of group money in the first few weeks of the trip. But of course I didn’t think of it at the time, and only dwelt on what would surely have been the most stunning and witty riposte in the history of disagreement while stewing for some hours after the incident.

I asked Lovey if he would drive Fez and he made it very clear he was going to drive Ziggy from then on. And there it was: battle lines.

Megan and I couldn’t help but feel smug when, two days later, he wrecked the oil pan on the Mercedes by ploughing over some loose stones. Careless, careless.

J Love was good company half the time, but sometimes he could be very difficult. “He’s spent all day storming around like a four-year-old toddler,” admitted Brady, exhausted from spending a day in the car with him.

The two had been riding together since Brady arrived, and I called them the Brady Bunch. One night I found them wrapped up watching Brokeback Mountain in the car, it was quite romantic and I was very jealous.

So now it was mostly Megan, Marlena and me in Fez, Lovey and Brady in Ziggy, Tony and Zsofi in Dante, and Carlos and OJ in Gunther. The fixed divisions were a little weird, but they certainly made me more protective of my car as I became keen to look after old Fez better and check him out more regularly.

Megan and Marlena were good company, always laughing about something, and the three of us got on well, and I felt protective of them. It was nice to feel like someone had your back.

The Darvaza Gas Crater

I was keen to explore Ashgabat, but there wasn’t much time, and Tony told me there was something much better to see. He said there was a crater in the desert filled with fire, which he said burned constantly, day and night. Our guide had never been, but we knew it was near the town of Darvaza out in the middle of the desert.

So again we headed into the vast, barren emptiness - yellow, black and grey sands, bearded with dry brown shrubs that spiked bare feet. The road began as an artery but gradually became a vein before squeezing into a capillary and fizzling out into the dunes. It was a long, hot drive but as the sky darkened, a dim and distant halo developed like a Polaroid in the dusk. It was far from the road, the Trabbis would never make it, but we stumbled upon some tents and the semi-nomads there agreed to take us. We piled into the back of an old Soviet truck, and even that thing struggled in the dunes, but the guy kept letting air out of the tyres to increase the traction, and eventually we cleared the steeper mounds.

In the waving sands I lost all sense of perspective, and despite seeing the glow on the horizon, I couldn’t work out how big the crater would be. It had been quite a journey out into the nothingness, but when we arrived there was a collective sigh of relief, then whoops of amazement when the scale of the crater became clear.

A huge oval hole brimming with fire, it must have been 100m across and 50m deep. Buttresses of sharp rock ribbed up the sides of the pit, awash with yellow and orange flames. Plumes of bright fire shot from jets in the centre of the crater, dampening down momentarily, then erupting high into the air. The whole thing glowed like amber melting in a campfire.

Dante’s inferno, the fires of hell, Mordor - I half expected Frodo to turn up and hurl the ring in - a truly magnificent sight. I stood at the crater’s edge and felt the bright warmth on my skin, then a gust of wind threw the full force of the heat at me, making my eyelids prickle and forcing me to leap away, shielding my face. It was impossibly hot.

I asked the truck driver who had dropped us off where the fire had come from. He didn’t know, but said it had been there for the 21 years of his life. Maybe forever. Was it some natural phenomena? If it had existed for centuries, here in of all places the land of Zoroaster, then surely temples would be all around. Fire worshippers would have had a field day. I could imagine the offerings being thrown into the flaming crater. It would be a wonder with a global reputation.

No, it must be a modern creation. Ilya agreed. “I think maybe there was an explosion here and many people died,” he told me cryptically, digging deep in his vodka-sodden mind, but he couldn’t expand or follow the thought any further.

I wandered around the crater looking for signs and found a bundle of twisted and broken metal pipes leading from the ground out into the crater, where they had snapped off and burned. It looked like a gas pipe, which made sense. Perhaps the Soviets or Russians were drilling, maybe there was an accident, an explosion. The crater caught fire and rather than explain what had happened they simply closed off the area and left it to burn out. But the fire didn’t burn out, and it will burn on, until it has sucked all the gas from its reserves below the surface.

The flames threw yellowish light onto a tall dune next to the crater. At the top someone had piled rocks in a sort of monument, the ghostly column flickering like a strobe above us as we laid out mats and slept in the fire’s warm breeze. It was Marlena’s birthday and she stayed up late drinking a merry amount with Megan and Tony. Zsofi, Lovey and Brady stayed up too, experimenting with filming the flames, but I was exhausted and drifted easily into a comfortable doze in the blinking light.

Our guide had met us in a smart shirt, with suit trousers and shiny shoes. But his dress had slowly disintegrated and as we broke camp the next morning I noticed that he was a bit of a wreck. His shirt was unbuttoned and hanging open, his chest exposed, trousers replaced with cargo pants, his hair scuffed up, eyes wild and nails dirty.

The Trabant Trek effect.

A Country You Cannot Leave

The oil pan on the Mercedes smashed again while we were heading from the fire crater to the border. It was terrible timing. Our visas had just a day left on them, and Turkmenistan is not a good place to overstay your welcome. Luckily I had struck up a conversation with a man at a nearby bazaar. He randomly gave me a tape of local music, and later happened to pass us sitting on the side of the road. He invited us back to his house for dinner and a place to stay, at considerable risk to himself. Foreigners are supposed to be registered every night in Turkmenistan. We ate in the Turkmen style, sharing a few big bowls between everyone, and drank in Russian style, knocking back shot after shot of vodka with fizzy pop chasers.

***

“I like you, Dan, I think you might be Russian,” Ilya told me the next morning. A curious assessment based, as far as I could tell, on my ability to drink silly amounts of vodka, go to sleep at the table, wear a skirt and fall over in the shower, gashing my back to the extent that I needed medical attention and three injections.

Megan: “Oh god, you’re still bleeding.”

A new word entered my dictionary. Subcutaneous - as in “it’s a subcutaneous injection” - an injection under the skin, but not into the muscle. I had one of those and two intramuscular (they do go into the muscle). I’m not sure what they were, tetanus maybe, but the next day I developed a fever, cold sweats and diarrhoea. I was lucky that Marlena is a trained nurse, and she and Megan regularly cleaned the wound and changed the bandage. An infection in that environment could have been nasty.

The lads managed to get the Mercedes repaired and we got to the border just before it closed, only to be told that it wasn’t the correct point of departure. We were meant to be at a crossing 100km away. Despite our protestations, they wouldn’t let us out of the country.

When foreigners overstay their visa in Turkmenistan a committee is formed to discuss what to do with them and reissue the paperwork. This hideous bureaucracy was a parting gift from the Soviets, along with a fierce drinking culture and a penchant for ruthless dictators. We would have to wait for the committee’s decision.

Because our papers had all expired Ilya warned us that it was dangerous to head into the nearby town, which, like the rest of the country, was swarming with police.

So we had no choice but to wait it out there on the Turkmen-Uzbek border, a strip of dusty soil crowded with queuing trans-nationals and hawkers flogging knock-off electronics. Not the best place to recover from a gouge in your back and the shits.

Marlena, who had already been with us a few weeks longer than expected, decided she wasn’t going to get drawn into our border saga, and opted to head back to Ashgabat and try to get a flight home. Even that wasn’t simple, and the poor girl ended up stranded in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, for two days waiting for her embassy to rescue her. It was sad to see her go, especially for Megan as the pair shared a real rapport. But she needed to get home to her studies and she’d pushed it long enough. We weren’t really in the right place for any kind of leaving bash, she just gave us a wave, jumped in a taxi, and that was that.

The rest of us sat in that checkpoint sandstorm for three days while a constant stream of Uzbeks and Turkmen examined the cars, tapped at the chassis, demanded to see the engines and tried to buy things from us. Every day we thought we’d get out of there, but always Ilya would turn up to tell us there had been another delay. The incessant attention became wearing and I stopped responding when the thousandth person asked what my name was.

Despite Ilya’s warnings about going into town, no one could stand the border crossing any longer. Three days of sitting in sand was too much, so we headed out to find a café to relax, eat and contact our embassies about the problems we were having getting out of Turkmenistan and the exorbitant fees the travel agency and the government were demanding to process our paperwork.

Anyway the traffic cops who lined the streets didn’t have cars or radios, just whistles, and we soon learned to speed up and look the other way when we heard them - how could they catch us? It became a cat and mouse game around the city, avoiding eye contact with the police when they attempted to flag us down.

Maybe the game antagonised them. We can’t be sure.

Things seemed to be going fine; people were unwinding, we had a beer and some good food. Then the police turned up, called us out of the restaurant and said they were arresting us for having dirty cars. The Trabbis had gone 6,000km through dense forests, high mountains, choking cities and dusty deserts without a wash and they’d picked up a little muck. It appeared that this was a serious offence in Turkmenistan where automobile care was clearly more important than running water or an ATM.

The cops wanted us to go to an expensive carwash, but OJ negotiated and we managed to get a local to wash our cars with a bucket for a dollar each. We had so little money left that Ilya paid.

We pulled up in an empty car park overlooked by a block of flats. Within minutes there were Turkmen swarming over us. All ages of them, kids on their way home from school, teenage girls, giggly and practising English, old men wanting to know the cost of the Trabbis, young men wanting to see our mobile phones. Two police cars watched over it all. Things got so crazy that a man with a wheelbarrow turned up to sell watermelons to the crowd.

“Do these people have nothing better to do?” TP asked. Perhaps not. But I guess we were quite a sight for the locals. The attention really seemed to rile the police. The poor chaps wanted to throw the book at us for having dirty cars and ended up policing a mass public demonstration. They became enraged and demanded we form a column and follow them. Some kind of police chief turned up and Ilya, who I think had been threatened, started to get angry and nervous.

There was a lot of discussion and then they led us out of the town and told us never to return. We were banished.

The KGB Are Here

The police took us to a closed, out-of-town bazaar, the nearest Turkmenistan has come to a mall. It was a couple of acres of empty stands and trucks swarming with mosquitoes and conditioned by a dusty breeze. The police were determined to lock us in. This caused some consternation, particularly among the Americans who refused at first to even enter the place. Carlos and I weren’t as bothered - it seemed a good spot for a kick about.

“They want to help you - you cannot stay on the street, it is not safe. They think it is better for you to stay here,” Ilya explained, but no one really believed him as we’d been living on the streets for days now. No, it was clear that we’d been locked up.

Thankfully there was a bar full of truckers on site. Ilya was straight in there buying the vodka, so Megan, Carlos and I joined him. It gave me an opportunity to chat to a few people about life in Turkmenistan.

“A few years ago there were people who wanted a revolution,” a truck driver told me, “and there were a lot of important people who said a lot of stupid things on TV. But we knew they were not stupid, we knew these people so we believe what they say.

“But about two years ago they all die. They don’t just get killed in one day - it is many things, injections and things over a long time. But they all go.

“I should not be talking to you, it may be dangerous for me,” the man said, reproaching himself for letting the vodka loosen his tongue. “Many people disappear, yes, many people.”

I asked him whether he knew anyone who had disappeared.

“Yes, a friend of a girl I used to work with. He was a political activist who wanted revolution. One day he was just disappeared. Yes, many people disappear. But this is the way it is. It is like this since Stalin, it has always been the way. I hope I am still alive in the morning.

“People have many thoughts of revolution. But with so many police everywhere, always watching, there is no chance of revolution. People think of it but there is no way.”

Carlos and I stayed in the café for a few hours to learn Russian swear-words from farmers. When I wobbled out of the place after one too many toasts I found Ilya walking through the darkness.

“Two men from the KGB are here.”

Words to send a chill down anyone’s spine. Why?

“It’s complicated, things are very strange. It is a long story. Over there are many drug makers,” he gestured towards the far wall of the compound, “so the KGB are here to protect you.”

I said that I wanted to meet them, so he took me over. The officers were typical Turkmen opposites. One was a tall, dark haired man in his thirties with an intelligent face. His assistant was squat and plump with a broad hazelnut head, wearing what looked like a GAP outfit - fitted stripy jumper, dark jeans and loafers. They seemed friendly enough. But it was an odd feeling being watched. I couldn’t get used to it. I asked Ilya whether they were there every night. “No, they are only here now to look after you. If anything strange happens you must find them.”

I wondered what he meant by anything strange, but he waved me away and talked with them in Russian.

Later we wandered back up to the café and Ilya opened up a little. The KGB is now known as the KMB - the Committee of National Defence. Different name, same job. Are they here to protect us or watch us? “Yes they protect you, but it is also desirable for them to watch you.”

Are we in trouble?

“Not you. But maybe me. This could be a problem for me. Maybe I disappear now,” he smirked. “Until a few months ago this whole province was closed off. You needed a special permit to go here, it took two weeks to get one even for me. It is because it is on the border with Uzbekistan. But the new president he makes it free to go anywhere.”

I asked one of the KGB why the area was closed off when Turkmenistan had good relations with Uzbekistan and had declared neutrality. “It is the border,” he explained, “you must be careful.”

“Yes, we keep a pretty close eye on the Welsh,” I told him, and he laughed.

Half an hour later I heard shouting from near the gate to the compound. I faked taking a pee and went to investigate. I saw Ilya getting dragged away by an official. He returned ten minutes later with a thick set Turkmen.

“We have to move,” he told me, seeming shaken and avoiding eye contact, “you are honoured guests. It is not right for you to stay here in this bazaar.”

I couldn’t help but laugh - honoured guests who’d been banished from the city and imprisoned in a mosquito-infested sandpit with the KGB for company.

“These people are from immigration,” he gestured at a dark car, “they say it is not right that foreigners are camped here, just five kilometres from the border.”

We had spent the previous three nights camping literally on the Uzbek border.

“You must stay in a hotel.”

It was ridiculous. The street cops had put us there, the KGB had decided just to watch us, and now the border police wanted to haul us back into the city.

“It is illegal for foreigners to stay outside. They must be registered at a hotel. This is the law,” Ilya added with a shrug.

We had no choice. We drove back in a surreal convoy with police, immigration and KGB vehicles to a hotel that was actually a worse place to sleep than the bazaar. We crammed in, four to a room, and I spent the whole night knocking mosquitoes and bed bugs away, and trying to avoid lying on the gash in my back. I rose early just to get out of the filthy pit and again waited for the Turkmen to let me leave their country.

But more delays, more paperwork, more problems with our guide. When I met Ilya in the morning he already had a beer in his hand and was talking about being robbed by the police. He said they had beaten him.

In a different country our guide may have been tempted to abandon us in the face of this fierce stream of misfortune. But we were Ilya’s problem and his responsibility, and he knew he would be punished if he did not keep us out of trouble and get us out of the country. But he seemed resigned to punishment.

By the time we got our new visas the border had closed, so we spent yet another night camping on a sandy crossroads.

“I’m sick of this shit. I promise you now I am never coming back to this country,” was OJ’s analysis. Turkmenistan had divided opinions. Certainly OJ and Lovey hated the place, and even the normally unflappable Tony had let his exasperation show. But I felt a little more reserved. We were the ones who overstayed our visas, and although it wasn’t our fault that the Mercedes broke, we had to deal with the consequences - five days of bureaucracy. We knew when we entered the country that we weren’t meant to go anywhere without a guide and the correct papers, and that we should be registered at a hotel in every city. We were told that not cleaning our cars would attract unwanted attention. But we just ploughed on, convinced of our inalienable right to freedoms that in Turkmenistan have yet to be won. Turkmenistan operated a different system, and I was pleased to get an understanding of it, if only to more greatly respect the liberties I took for granted back home.

***

I got up full of hope that we’d make it out of the country, five days later than we’d planned. But within minutes of breaking camp and pulling away, the gearbox broke on Fez. It was embarrassing being towed up to the border, but Tony put a positive spin on it: “People have crossed borders by foot, on planes, by boat and on trains. But how many people can say they’ve been dragged across a border?”

Thanks, TP.

We got there at lunchtime, so of course the border was closed. We were sitting there in a totalitarian, isolationist, pariah state, hidden away in Central Asia, impervious to all Western influences but one - the all-pervading power of euro-cheese. Even there, on the Turkmen-Uzbek border, they played Steps. Could the agony get any worse?

We were all hot, thirsty and frustrated, so Tony and Zsofi headed up the road in Dante to find water. But the hours ticked by and they didn’t return. They had been arrested in town for not having any papers. It’s quite easy to get arrested in Turkmenistan. There was plenty of groaning, but Ilya went to negotiate and we got them back just as the border was closing. We were fined $150 for something as we left the country. But we had literally nothing, so Ilya had to pay.

It felt like escaping from a prisoner of war camp - Carlos and I whooped and high-fived when we saw the “Welcome to Uzbekistan” sign. Through some strange quirk of fate I entered the country shoeless and topless, walking behind the rest of the cars. I genuinely felt like I was in a prisoner exchange, crossing the 500m of no-man’s-land between the countries.

The Uzbek guards kindly stayed open late to process us, and then let us out into the night. We were still towing Fez.

Uzbekistan

With Marlena gone it was just Megan and me in Fez, and we got on well. She was no girly girl, very hands on with the car, push starting it, filling the oil, defiantly driving around despite the jeers of men who found it hilarious that there was a woman behind the wheel. She was a great communicator, always expressing what was on her mind through a combination of word, song and charades. Often I heard her singing strange ditties to stray animals.

Trapped in a five-foot by six-foot plastic lunch box for three months, you get to know someone. Not that I could tell you too much about her history, her family, her past. Her parents were teachers with the military, she had lived on military bases in Turkey, Korea and Europe. She had a brother and a sister, both older. She was freeloading at her sister’s and did a mundane office job before hitting the Trek.

But once you’re Trekking these details seem pretty irrelevant. More importantly, I could tell you that she was always keen to fix a flat, get dirty filling up the car and insisted on carrying her own stuff. She hid food in restaurants to take out to stray dogs. The sight of a camel, yak or bison would make her laugh out loud. She sang to animals. She didn’t like sleeping in tents, could drive long into the night and rose before most. She wasn’t squeamish and knew how to dress a wound. She could be confrontational.

She could be pessimistic, and tended to fear the worst. If something went wrong, which was roughly every other hour, she could quickly freak out - “aagh, it’s the end of the world” - and rather than try and deal with the issue, she tended to rip holes in everyone else’s suggestions. She really wanted to be taken seriously by the boys, but her nay saying approach meant she often got ignored - which pissed her off (“I suggested that, like, twenty minutes ago”). But generally she was good, easy company, we laughed a lot and looked out for each other. She changed the bandage on my back and kindly told me when I smelt. I provided her with countless hours of wit and diversion, which she seemed to enjoy the most while listening to her headphones on full volume.

Of course, we could wind each other up, but there was a refreshing spirit of camaraderie in Fez as we escaped the terrors of Turkmenistan.

Khiva: Sanitising The Slave Trade

Whenever we entered a new city it was Trabant Trek custom to drive around in laps, hopelessly lost, rapidly stressing out as various wants failed to be sated. Some of us needed internet, others food, for some the priority was a bed, others were gagging for a bar. This city centre dance did serve to help orientate us, but also ensured we arrived in frustrated mood, having spent an hour pissing about in headless chicken mode.

Having already passed one Khivan junior school three times to the sound of loud shouting, we should have known that parking outside would attract a lot of attention. As a sortie headed out to find accommodation, those who remained with the cars were swamped by kids in uniform. Initially they circled us guardedly, but soon the braver souls piped up with Asia’s favourite question: “Where you from?”

This question must have been ingrained in the locals from an early age, and it was the only English that older folk seemed to know. For some of us it took on an almost shamanistic quality, having an instant irritating effect. I could be sitting, working, reading, writing, talking, even sleeping, and someone would approach, tap me on the shoulder and insist, “Where you from?”

“England.”

“Oh.”

Then just stares. No follow up. For me the silence used to be vaguely awkward, although the locals always seemed happy enough to stare, but by Khiva I had begun to enjoy the empty pause, imagining my would-be interrogator might feel some discomfort. I hoped that every second that ticked by they were realising the futility of their question. What were they hoping to get from that single use of dodgy English? Did they really need to wake me up?

Now I know why all those beer-bellied builders get a British Bulldog tattooed on their arm. It is so, when they are on holiday in the Costa del Sol, drinking Stella with their shirt off, the answer to the question on everyone’s lips is emblazoned garishly across their upper arm.

I considered my first tattoo: Britannia, riding a bulldog, draped in a Union Jack, underlined with the words “English, so sod off.”

As I said, arriving in a new city could be frustrating.

After the advance party had found a place to stay, we pulled the cars inside the ancient city walls and found a welcomingly clean guesthouse. I shared a room with Megan and in the morning we were served an eclectic breakfast - honeyed figs, sweet oat biscuits, a fried egg, strips of tomato wrapped in baked eggplant, cheese, sausage and sweet, watery tea.

Having spent so long in enforced company, I was keen to do some exploring on my own. But for some reason I felt unable to explain this to Megan and so resorted to giving her the slip, a cowardly manoeuvre I felt bad about. And Megan, not being the type to shy away from confrontation, brought it up later that day.

“You ditched me.”

“Uuh… yeah… sorry, I just sort of wandered off…”

“You ditched me.”

Khiva is a strange place. There has been a city there for millennia, but its golden age was that of the Silk Road and the slave trade. When, in turn, the road and the trade dried up, the city fell off the map - a Russian protectorate, slowly dying in the desert. But the Soviets decided to make the best of the place and embarked on a huge programme of restoration. This meant forcing out many of the inhabitants of the old walled city, sending them to live in new Soviet concrete apartments, and rebuilding their former homes. The result is a sort of living outdoor museum. Everywhere is the sound of workmen scrubbing the place up, plastering, tiling and hammering exposed beams protruding, petrified and ancient, from the sides of narrow, cool alleys. Gaggles of old French tourists, the first we’d seen in a long time, added to the exhibition ambience.

People do live there, but it felt like a mock up. The town didn’t seem like a home, there was none of the detritus of thousands of years of existence. Most signs of the past had been lost in the restored buildings. And such empty streets - Khiva was a ghost town. I wanted to feel the vibrations of its history, but instead felt the sun dazzling off the newly buffed city walls.

There were some signs of life. Baked clay ovens stood outside a few homes, looking like giant termite nests, with gaping sooty holes in the top. But only the riveted cart tracks in the stone paving betrayed centuries of use.

As a prototype for future restoration projects, I wasn’t convinced. Would Stonehenge bear the same ethereal magic if it was scrubbed up and polished, its fallen stones righted, its altar restored? I doubt it. Part of the beauty of visiting these places is seeing what hand time has dealt them. Their decrepitude tells its own story.

***

Just like cities in the West, Khiva has its own financial district. Not quite a Wall Street or Canary Wharf, actually it’s a bunch of men sitting around the bazaar looking bored and fanning themselves with huge stacks of cash. Currency is an issue in Uzbekistan. With the highest denomination of bill being worth about 40p, you have little choice but to wheel around barrows of the stuff, and when I asked to change a $50 bill a local had to run out back and chop down a small forest to make the notes.

Strolling among the stands of walnuts, raisins, almonds, mink hats, wolf- skin waistcoats and surprisingly large amounts of toiletries, it was difficult to imagine the place filled with the slaves who made the city rich. The entrance to the bazaar is the East Gate, or Executioners Gate, a long dark passage with grated alcoves on each side where the Persian, Turcoman and Russian slaves would sit and starve until they were bought. A Russian would cost you four good camels, a Persian just a donkey. The rare visitors who made it to Khiva and back described seeing thousands of slaves manacled together in the market. Those who tried to escape would be nailed to the East Gate by their ears and left to bake in the extreme Uzbek sun. Lovejoy?

A Frightening Example Of The Trabant Trek Approach In The Qizilqum Desert

TP, OJ and Carlos spent much of the second day in Khiva working on Fez. The car still had a problem with the front right wheel, what would become known to all of us as “the bearing issue”, and, as we prepared to leave, TP didn’t seem too convinced that the situation had been resolved.

“There is a chance that the wheel will come off while you’re driving, so watch out for that,” he said, which is possibly some of the least reassuring advice a mechanic has ever given. I pressed him on what I should be looking out for and he shrugged: “Strange noises… if it comes off you’ll know.”

I’m not too good at identifying “strange noises” in cars, particularly in rattling old Trabbis on terrible roads, and I wasn’t entirely comfortable with the thought of the wheel falling off. Wouldn’t this have some influence on my control of the vehicle? Was that dangerous? TP seemed happy enough, he was always my yardstick on mechanical matters, and so I put the thought out of my mind.

We left Khiva in similar fashion to our arrival, with two hours of driving around in circles trying to find the right road. You’d have thought the road to the capital, Bukhara, would be well signposted. Maybe it was, but I’m not sure we found it. The road we took was vaguely well paved but entirely unlit as we followed it into the night. Somewhere along the way the decision was made to stop and sleep.

***

I woke up in the desert. As far as the eye could see it was rolling dunes and tufts of dense weed. Definitely the desert. We had approached this leg as we did most, making a rough stab at the distance by looking at the sketchy diagram in the guidebook, then going for it. We estimated it was about 400km, maybe a seven-hour drive? But we didn’t realise we would be crossing a desert, and the feeble Trabbi headlamps hadn’t illuminated this important fact during our rough night time excursion. So I was a little surprised to be out among the dunes, but in good spirits as we slowly pulled ourselves together and headed off.

We drove for hours in that vast, lifeless emptiness without seeing much, and then around noon, someone ran out of petrol. This was a bad sign. Once one car had run out you could be sure the others weren’t far behind. But no one had thought to fill the spare tanks, assuming there would be somewhere to buy gas along the way. There wasn’t. And so we were stranded about 250km into a 400km-wide stretch of the blazingly hot, frighteningly empty and practically uninhabited Qizilqum Desert.

This sort of situation is beyond the realms of naivety and far into the now well-trodden frontiers of our stupidity. Who goes into the desert without enough petrol to get out again? And without any food or more than a few gulps of water between eight people? It is genuinely mind-boggling, and the pull-quotes write themselves:

“They didn’t respect the desert.”

“They were under-prepared.”

“They were thick as pig shit.”

All true.

Fez had the most fuel left, so Megan and I volunteered to take all the spare petrol cans and head off in search of fuel. To add to the fun we only had a handful of Uzbek money, and a few dollars. To increase our range some excess petrol was decanted from Dante into Fez and we set off, leaving the rest of the group standing around in the middle of nowhere.

It was quite a relief to be on the road with just Fez and making our own decisions without the committee meetings. Not that there were too many decisions: just follow this long, straight road until you find fuel. But the sensation slowly turned to trepidation as we watched the kilometres tick by on the odometer, our own feeble fuel supply running down with few signs of life.

We passed a petrol station that looked like it had been abandoned for some time, then found a man at a truck stop who waved us a long way down the road when we asked for benzene. We banged on the window of another abandoned petrol station, to no avail, but this time I noticed a man nearby riding a donkey. Now I know donkeys don’t need petrol to run, but things were getting desperate.

“Shall I ask him?”

Megan laughed, “Why not?”

He was a scruffy little man, so small his donkey looked like a stallion. It wore a saddle made of blankets, with no stirrups, and the man guided it by poking it in the rump with a sharp stick. We got chatting with the wee chap, who seemed as surprised to see us as we were to see him, and he even let me have a ride on his donkey, who we learned was called Pedro. We raised the benzene situation and were pretty stunned when he gestured that he could help, saddled up and trotted off into the desert. He disappeared behind some dunes, and Megan and I looked at each other.

“Is he coming back?”

After a while the huddled little shape reappeared, this time carrying a couple of Coke bottles. They were full of petrol. Amazing. Out there in the Uzbek desert, Pedro the Donkey and Petrol Man. What a double act.

We bought both bottles at an extortionate price, exchanged a lot of back slapping, hugging and posing for photos, then headed off, with another 20km added to our range.

This pattern continued for the next two hours. We would get worryingly close to running out of fuel, eventually stumble across someone who could sell us a Coke bottle full, then limp on into the desert until we found another stop. It was edge of the seat stuff, as running out of fuel out there would not have been pretty.

Gradually the desert gave way to irrigation and foliage, then low-rise homes and shops - a great relief. When we finally reached Bukhara we spent the last of our money on a well-deserved plate of food, then Megan got a cab into the city to find a cash point and fill the tanks. I slept in the sun for an hour, then we made the two-and-a-half-hour drive back into the desert. The round trip was a little like running out of fuel in London and sending someone to Manchester to get some. Other than having to smuggle the illegal plastic petrol containers through a police checkpoint outside the city, and a scary moment when the guard lent into the car to light a cigarette literally inches from our fuming gas cans, all went well.

Shortly before nightfall, and seven hours after leaving them, we found the group, limping along the highway towing the Mercedes. Tony ran out of Dante cheering and hugged us. It felt good. The Muppets had become the cavalry. The others had found twenty litres between them and begun to slowly crawl towards the city, but they wouldn’t have made it without us.

Tony: “We thought we’d lost you. We thought you must have broken down somewhere and were just sitting it out. Aaah, man, it’s good to see you guys.”

We’d come bearing significant luxuries - hard bread, stale biscuits and warm water, and we all sat around eating, drinking and celebrating. Another scrape with catastrophe under our belts.

Bukhara

We arrived late in Bukhara and managed to find a place to stay, but pretty much everything else was closed and OJ was hungry. You wouldn’t like OJ when he’s hungry.

As I have mentioned, OJ is a big man with a big appetite. The sort of man who snacks on a king-size Snickers with a 1.5 litre bottle of Coke, burps and is hungry again. I would go so far as to say that OJ’s food fetish began to wear me down. I like to eat - my belly is testament to that - but I’m not especially into food or cooking. OJ could spend an entire evening meal talking about the stuff: the best paella he ever had, the traditional method for making chapattis in India, the various pros and cons of long grained rice versus its short grained cousin. Lovey and Tony loved these conversations too, sometimes comparing burrito places in DC or launching into long diatribes about mayonnaise. This used to bore me senseless.

That night OJ charged around the city looking for food, frightening anyone who witnessed him. After finding nothing but frustration, and slightly scared that OJ might start eating small children, we ended up cooking noodles in the kitchen of the guesthouse.

Since the vehicular segregation in Turkmenistan, partnerships had formed across the group - Tony and Zsofi, Lovey and Brady, OJ and Carlos, and now Megan and me.

The confirmation of our new alliance came in Bukhara. She found the guesthouse that could take us all in, and so got first dibs on the best room. It had a double bed, air con, en suite, TV, fresh, clean sheets, and I was invited to share in the luxury.

It was probably the nicest place we had stayed in months. I enjoyed it so much I even did my washing in the shower, a rare occurrence. In that situation I guess there was a chance of romance blossoming. It didn’t, though that didn’t stop the rumours. Why let the truth hinder the gossip? Instead we were accomplices, sharing each other’s grievances and the inevitable bitching. It was a good friendship.

I had a brief look around Bukhara, but wasn’t especially impressed. In fact, I remember it best for the guesthouse. Time was still against us, so we only lingered a couple of nights before continuing east, towards one of the highlights of Central Asia - to Samarkand.

Maps? Where We’re Going We Don’t Need Maps

Did I mention that we didn’t have any maps? We didn’t have any maps. It’s true. We bought maps for all of the 21 countries we were planning to cross. But OJ left them on the shelf of his apartment in Washington DC. So, for six weeks and 8,000km we had been asking directions.

“Samarkand,” I’d shout out of the window at terrified pedestrians.

We’d pull over in Uzbek towns and ask for directions to the Tajik capital of Dushanbe, which is a little like pulling over in Surbiton and asking a passer-by if he knows the way to Aberdeen.

Initially the locals would gaff off in their local tongue, but when they realised our incomprehension they would join us in pointing and gesticulating. In Europe people tend to point in short sharp motions, angular juts and thrusts. In Central Asia the movements are more curved, a right hand turn becoming one half of a breaststroke. We were often lost, especially in cities, and adopted a pragmatic approach to traffic laws, performing U-turns, illegal lefts and pulling over in terribly unsafe places.

I wasn’t entirely truthful; we did have some maps: the little diagrams in our guidebooks. But they were clearly not designed for road travel, bearing few road names, a strange sense of distance and marking junctions haphazardly.

I don’t know how many hours our lack of maps cost us, probably in the hundreds. But in a strange way it was liberating - blundering from one place to the next relying on our own initiative and the courtesy of strangers.

“Excuse me. Can you point me in the direction of Cambodia?”

To Samarkand

London is big on stone, but in Samarkand the thing is tiles - clay baked aquatic colours pieced together in delicate mosaics that shimmer across the buildings in the yellow wash Uzbek sun. If ever you need someone to retile your bathroom, I would recommend an Uzbek.

People have lived and traded around Samarkand since before Christ, and even Alexander the Great was struck with wonder at the ancient city. But Ghengis Khan sacked and levelled the place, leaving it a shell until another famous Mongol leader made it his capital.

Fourteenth-century Samarkand was the centre of an empire that sent hordes pillaging their way across India, the Caucasus, the Middle East, and deep into Eastern Europe, destroying what they couldn’t steal. The man in charge was Timur the Lame, Timurlane, a petty chief from a small Mongol settlement 50km from Samarkand. His reputation is as hero to his people and villain to his enemies, and history has struggled to judge him. He marked the cities he sacked with huge pyramids of human skulls - 80,000 counted in a heap in Baghdad alone - and historians estimate the numbers he slaughtered in the tens of millions. But he was a lover and collector of fine art, and a keen chess player who invented his own more complex version of the game, with twice as many pieces and a larger board.

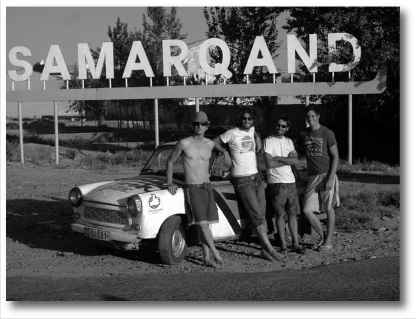

Brady, Lovey Carlos and OJ arrive in Samarkand

His victories stretched from Poland to Delhi, and although he sacked much of what he conquered, he took artists, scholars, philosophers and craftsmen back to Samarkand, which became a glorious hub of creativity, propped up by Timur’s ruthlessness.

The travellers and traders who returned from the empire’s capital spoke of a vast and beautiful city and it became romanticised in Western imaginations. To Poe, Marlowe and Keats this was a city that encapsulated the majesty and mystery of the East.

Even now the city’s skyline is dominated by the imposing turquoise dome of the Bibi Khanum Mosque, built using the riches looted from India in the winter of 1398 when Timur sacked Delhi and beheaded 100,000 prisoners. Ninety elephants were needed to bring the haul back to Samarkand.

The mosque’s dome towers over the modern buildings that surround it, as if it were built by a race of giants or aliens. Arriving at its gargantuan arch it is easy to imagine how dumbstruck a foreign traveller would have been in the fourteenth century. There would have been few other monuments of such height and scale in the known world, apart perhaps from the Aya Sophia in Istanbul.

Yet the building’s ambition was also its undoing. The great dome of the mosque was too big, and within years of completion great cracks had appeared in it and the building quickly became unsafe. The dome is a nice analogy for the end of the great empire - it reached its zenith, and the fulfilment of its own opulent glory was also its death sentence. Timurlane’s empire, like his architecture, became too big, too overstretched and ultimately crumbled from within.

The best story is every guide’s favourite. An inscription on Timurlane’s mausoleum warned that anyone who disturbed the great Khan’s grave would unleash war on the land. In 1941 Soviet archaeologists opened up the cracked jade tomb that had sat in the Samarkand necropolis for five hundred and fifty years. Inside they found the perfectly preserved body of a short man, with Mongol features, who was lame on his right side. Flecks of muscle still clung to his body, and a dark moustache still whisped across his lips. Within a few days Hitler launched Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of Russia. True story.

It is a credit to the Soviets that the buildings have been so meticulously restored. By the end of the nineteenth century they were little more than crumbling ruins. Many of the domes had collapsed, the minarets fallen in on themselves, tiles and mosaics carried away. But the Soviets went about the renovation with vigour and their work is magnificent. Once again the buildings gleam with the reflection of bright mosaics, particularly the necropolis, which has stood for millennia, stretching back to before Timur’s time. Even Genghis Khan’s troops refused to touch it.

The restoration of Samarkand was so stunning it forced me to reassess my thoughts on Khiva. If Khiva had looked as ruined as pre-restoration Samarkand, would I have gone there at all?

I wish I had stayed longer. But as ever we were at the whim of immigration officials, who seemed determined not to issue us with decent length visas. So after just one night we left for the short trip to the Tajik border.

Chaos Theory

Chaos Theory: A water vole farts in the Thames, and tsunamis strike the coast of Fiji. Or something like that. A small opportunity missed or a detail overlooked had consequences stretching far into our trip.

Our water vole was the Baku-Turkmenbashi ferry. If that had taken the twelve hours it was meant to, rather than the four days it did, we would have got to Turkmenistan earlier and had time to make repairs and get out of the country without overstaying our visas. That would have saved us five days and a few hundred dollars. The delay impacted on our Uzbek visas, leaving us just six days in the country. You could spend six days in Samarkand alone. In the end we probably stayed a night too long in Bukhara, maybe even Khiva - we should have pushed on to the wonders of Samarkand earlier. Tashkent, Central Asia’s main city, got missed out altogether.

Perhaps if we’d not bargained so hard at the Baku port we would have got onto the earlier ferry. It left twelve hours before ours and may have ended up saving us a week. But I guess there is no planning for these circumstances. We arrived in Turkmenistan on 31 August. By 15 September we had covered just a couple of thousand kilometres. Constantly, whenever we hit the road, something went wrong. A car would break down, mostly Gunther, but Fez had trouble too. It seemed that we could only drive for an hour before a major stoppage and I don’t remember doing a decent ten-hour journey in the right direction. We ran out of gas, we ran out of water, we took a wrong turn, we broke down, we found a spot for a swim.

We left Uzbekistan on the last day of our visas, having barely spent any time in the country, and were now probably running about a week behind our loose schedule, despite all our efforts to catch up.

There were certain personal restraints on time. OJ and Tony P had promised loved ones that they would be home by the end of November and Zsofi needed to get back to Budapest around the same time so she could study for exams. Time is also money, and Megan was running out. For these reasons it was important not to get too bogged down.

But there were also official factors. We had our visas for Russia, which would be expensive and time consuming to replace. And we were well into the two-month process of applying for our China visas. So we had pretty set windows to get through Russia and China, and we were falling behind. We needed to make some time up, get some miles under our belt and claw back at our schedule.

In front of us stood the greatest physical barrier we had yet faced – the great jagged wall of mountains that is home to the Tajiks, rough, mountain tribes living in the least developed country in the region. For most of the 1970s and 1980s the country was a staging-post for Russia’s activity in Afghanistan, and just ten years before it was gripped in a bloody civil war. The long, porous boundary with Afghanistan was home to rebels, smugglers and warlords, the infrastructure in the mountains was harshly underdeveloped and opportunities for help, mechanical or medical, would be few and far between.

The route we hoped to take through the country was over one of the world’s great mountain ranges, one that no Trabant had ever tackled – the Pamirs. Nobody had any idea how the Trabbis would cope with the steep gradients we expected to encounter, or the extreme elevations, with some passes over 4,000m high.

Despite the challenges that loomed in the mountains on our horizon, spirits were high. It had been refreshing to do some genuine sightseeing in Uzbekistan, and there was a welcome lack of paperwork at border control as we entered Tajikistan.

Our new visas gave us a fortnight in the country, but we hoped to be through it in nine or ten days. Our optimism couldn’t have been more misplaced.