The Hiatus

Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan

26 September – 29 October 2007

Q) What do you call a Trabant that’s been driven to the top of a steep hill?

A) A bloody miracle.

The Pamir Highway

Retracing the steps we had taken the day before by Trabant, I was immediately struck by how different it was riding in a normal car. For the first time in two and a half months people weren’t staring at us.

Hey, it’s us.

But nothing.

No waving, no screaming, no kids running alongside our cars, no old men tapping on the chassis and raising querying brows. Even the police weren’t interested in stopping us. Our star had truly fallen. But we used to be famous. Whatever, get to the back of the line. We were just like any other backpackers, except there really weren’t too many other backpackers around.

But as I pushed myself back into the comfortable seats of our shared taxi I was secretly looking forward to being a casual tourist for a few weeks. I could revel in the anonymity. I wouldn’t have to get up at seven. There would be no worrying about the cars, the group, the plan, the money, the breakdowns and the myriad other daily concerns.

I guess Team Europe had the plum deal; we just had to get to Bishkek and sit tight. I didn’t know anything about the city, but it was the Kyrgyz capital and would surely have some welcome diversions. But Team USA would have to deal with the visa issues, and then wrestle the cars over the mountains. In retrospect I would like to have done it, but at that moment, in that comfortable, quiet interior, I was pleased to leave the Trek behind.

***

The Pamir Highway between Khorog and Murghab reminded me of the Turkmen desert, except freezing cold and two miles high. Millions of years ago it would have been a desert at a reasonable level - another chunk of rolling Central Asian plains - but the steady shove of the Indian subcontinent had raised it year by year until that bleak plain sat 4,500m high, incongruous in the mountains.

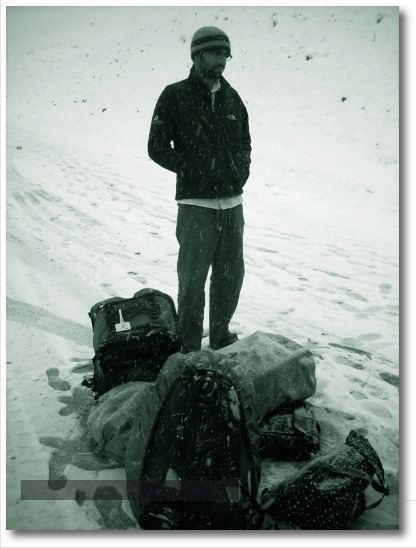

Carlos in our first snow storm

We stopped at thermal springs and dipped in boiling hot, greenish water that smelled of eggs. The flow had been funnelled into a small rest stop with a café and a TV. I imagined the other trekkers would be delighted to find that little oasis in the desert, and maybe spend some time there. But we had just half an hour as our shared taxi was keen to plough on. As was customary in the region, there were seven of us in the five-seater, with two crammed into the boot. Luckily we had sent our bags ahead.

We arrived after dark in Murghab and stayed at the Murghab Hotel, where there was only enough electricity to power two light bulbs. As there was one on in the kitchen, our group could only light one of our two rooms at a time. There was no heating and it was genuinely freezing. Washing my hands under the rusty tap outside felt like thrusting them into a furnace.

At dinner we sat on mats on the floor with an old man and his old son. The father was white haired and Chinese-looking, his eyes seemed almost closed, and he rocked back and forth when he laughed like an old bear. His son was deferential, filling up his father’s cup at every opportunity, and pausing to allow him to speak. The old man dipped hard Chinese bread into his tea. We shared two cups between us - one person would drain their ration then hand it back to the younger old man, who would pour the dregs into a dish, then refill the cup and pass it to the next person. It felt primitive and natural to share the simplest of commodities, hot water and a few tea leaves.

***

The next morning we went to hunt down the bags we had sent ahead and I got to see Murghab in the light. The town was a jagged mix of one-storey buildings connected by dirt tracks with one wide paved road running through it - the Pamir Highway itself. Deceptively large, there were 400 pupils at the local school. The following morning I walked in with one of them and, despite living in one of the most remote and isolated towns in the world, he had the same attitudes you’d expect of any fifteen-year-old. He hated learning the periodic table for chemistry, and didn’t know why he was studying Arabic, English, Russian, Chinese and Tajik.

We hired a 4x4 to take us and all our excess baggage to Osh in Kyrgyzstan, a twelve-hour drive. The scenery was far more spectacular than the previous day, a geologist’s dream. Out of endless desert sprung a huge icy lake of deep aquamarine formed by a meteor in another time. Peaty bogs turned to hard brown tundra and frozen streams irrigated the bleak permafrost. Thick yellow grass met jet-black sands and dense shrubs clung to orange earth. A swarm of sand floated like a heat haze on the horizon and, rising from the opaque mist, the hills escalated in tiered colours. Ochre sands and a kaleidoscope of stones flanked the arrow straight path.

Man had made little impression on that landscape. Just three signs of human existence: the long road, lined by electricity poles and flanked by the fiercely barbed-wire Chinese border. We hugged that border for hours, with its menacing lines of razors. I was surprised to find a lone gate in the fence, near to nothing, with no path leading up to it, but invitingly open.

We stopped at a mountain village for tea and were served by a strikingly good-looking family, high cheek-boned with broad honest faces, the epitome of mountain health. They served deer with hard bread and a sour yoghurt made of yak’s milk. To much amusement Zsofi dropped her purse into the toilet pit just as we were about to leave, and the husband had to fish it out with a pole.

The border was spectacularly located on a high pass, and it must be one of the world’s longest crossings - more than twenty kilometres of no-man’s-land between Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. At Kyrgyz customs Zsofi noticed the guards were tearing pages from the register to use as toilet paper.

The final border post was closed by the time we reached it, but after some negotiation we bribed the guard $10 to let us through. It was such a relief to leave Tajikistan behind; we’d been stuck there too long. None of us knew how long it would take Team USA to escape.

Impressions Of Osh And Bishkek

Osh is Kyrgyzstan’s second city, and famous for its bazaar. Though I’m not a big fan of markets, Carlos loved them, so we had to investigate. My favourite stall sold a single roller blade, four wind-dial telephones, a selection of second-hand electrical sockets, various ratchets, one faucet, two plates, a cashier’s tray, a wing mirror, one large cooking pot and assorted nuts, bolts and screws. This was the man’s entire business.

Cobblers lined a rusting bridge repairing tatty shoes over a dirty river. From the thick crowd an old man held my hand tight. “Manchester United?” he asked.

“Yes.”

“Aha,” he celebrated this victory of communication long and hard before expanding, “Anglia Ruski tree nil”

“Yes, we beat the Russians.”

“Aha,” another victory cry, but he still wouldn’t release my hand, “Chelsea?”

“No, Chelsea are boring, Chelsea eta skoochnaya.”

“Aha,” he loved that one and squeezed my hand tightly. The conversation was typical of my travels. Pretty much everywhere I have been in the world, except the United States, people speak the international language of football.

“Beckham, America?”

Even there, in that strange outpost of civilisation, Beckham’s move to the States was big news.

Many of the city’s buildings still bore communist murals depicting strong-boned, clean-shaven men in factory overalls and bright-eyed, independent women in jeans in front of ploughed field and assembly lines. At least Sovietism was a victory for women’s rights.

A fantastic variety of hats topped the streets. Little skull caps, clinging to the back of the head, sharp cut fedoras in pale blue with embroidered ribbons, the sweeping Pamir hat looking impossibly balanced and ready to topple.

***

In Kyrgyzstan one of our main sponsors, the pharmaceutical giant Richter, had a base. We met some of their representatives in Osh and they helped us out with new visas, and found us a car to Bishkek.

We arrived in the capital after a long and cold crossing over the mountains, where we were snowed in overnight. After so long sleeping rough in Tajikistan we were all looking forward to the accommodation Richter had promised to provide. We had dreams of hot showers, clean sheets and central heating. But when we started pulling into a downtrodden, ill-paved courtyard my heart sank. We got out of the car, and a thick breeze scooped up heaps of dust, sand and litter and swung them into the shawled faces of poor old ladies. This was not what we were hoping for.

Our apartment had the demoralising ambiance of a prison block - even the cockroaches looked embarrassed to be seen there. Then the cherry: no showers. It is hard to overstate my disappointment. It was the simplest of pleasures, but to be clean would have made a world of difference. After speaking to the housekeeper we were told there were public washrooms across the street.

Notes On Showering Etiquette In Central Asia

The showering situation was quite an adventure. The facilities were very much communal, shared between three large apartment blocks. Inside what I shall politely call the gentlemen’s washroom, but may be better termed a small, filthy cesspit, there were three showers, which in my experience were shared between six or seven people.

The routine was this: you jump in the shower for a quick rinse, wait for the naked men surrounding you to start staring, then step out and begin to lather yourself. You will have to wait near a shower for at least five minutes, dripping and soapy like some fluffy yeti, for a gap to appear beneath the crowded nozzles. When you see a space it is imperative to jump in quickly and wash off the suds, before the other nudies get annoyed.

You may then retreat to the relative safety of the dressing area, pleasantly decorated with live moss, where people perpetually leave the door open to the wider world, leaving you horribly at risk of a terrible exposure.

Of course, I always seemed to arrive in the washroom when there was a deep queue for each shower. So I would have to hover, in full naked glory, waiting for my go and wondering where to look. I normally stared at my miniature aeroplane bottle of shampoo, which was about the size of a teabag, its instructions written entirely in Russian, a language so foreign it uses a different alphabet and utterly, utterly indecipherable to me. I knew this ruse was wearing thin, but I had yet to work out the correct posture to adopt when standing in a room full of naked Kyrgyz.

But I tell you this: I saw more cock in those ten days than the preceding ten years. And the Asian penis has been hugely underestimated.

Crossroads: An Update

We were scattered. The team spread across two countries and three cities in and around Central Asia’s craggy, imposing mountain ranges.

Lovey’s trip to Dushanbe to sort out visas for our American contingent turned into a lengthy mission. The Tajik capital happened to be hosting an international conference and every hotel in the city was booked, forcing Lovey to prostitute himself to find a place to stay. The poor chap spent most of his days queuing and arguing at embassies, walking the same streets between the internet café, consulate and his accommodation.

OJ and Tony P, the other members of Team USA, were in Khorog, high in the Pamir Mountains. By email we had received the disturbing news that both of them were under house arrest, closely monitored by the Tajik police. In Tajikistan it was illegal for foreigners to be out without their passports, which Lovey had in Dushanbe, and the pair were repeatedly arrested during their first few days without documents.

You would think a six-foot-three goliath of a Yank and a moustachioed Mexican with a Mohawk would be able to escape attention in a small Tajik mountain village. Maybe the brightly coloured German cars blew their cover?

All I had to go on were a few emails, but I knew they had been subjected to constant police harassment and were bound to their home-stay, where, thankfully, the owners had taken pity and begun to feed them for free each night. I wasn’t sure what curious cabin fever their enforced proximity had created, but during a Gmail chat both complained to me, quite separately, that the other smelled.

Team Europe - Carlos, Zsofi and I - were settling into our accommodation, which may have been the inspiration for Prisoner Cell Block H, but without the lesbians. Actually we were probably Prisoner Cell Block Q or R, nothing as luxurious as H, where I heard they had their own shower.

Our continuing mission, to get to Cambodia, had taken some violent twists in the preceding weeks and now we were stalled, scattered and in limbo. Between us we needed new visas for the next four countries along our route: Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan and Russia. It being ex-Soviet territory, any brush with authority exposed you to the delightful whimsy of former Soviet bureaucracy, and the visas were a handful, taking a week to secure.

And all the delays added to a new and potentially much greater hurdle. Looming large in the distance was China, an undoubted highlight of the trip, a booming country and culture we were all desperate to taste. But also a system of paperwork and officialdom that made Turkmenistan look like a Parisian hippy community of liberal utopians.

To get the car papers for our expedition in China had taken three months and was costing us $8,000. Our points of entry and exit were fixed, as were the dates, and the Chinese insisted we pay to have a guide with us for the whole month. Hence the ridiculous costs involved.

We were supposed to be entering China from southern Mongolia, thousands of kilometres away, but it was pretty unfeasible that we would get there when our visa started in a fortnight. Infuriating we were already on China’s western frontier - both Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan had open borders with the country. But the Chinese were refusing to let us change our point of entry. This meant we would have to circumnavigate the whole of north-west China, a trip of thousands of kilometres up the length of Kazakhstan, across miles of Siberian wilderness and down through Mongolia, a country with more horses than cars.

Of course, this was our original route, but judging from previous form it would probably take three weeks to a month, and Team USA still had to make it over the Pamirs.

So we had to face up to the very real possibility that we might miss our visa dates and not be allowed into China. What could we do? Apply for a new visa? It would take at least two months to do and no one had the time or money to wait it out.

We therefore began to seriously contemplate an alternative to China. We had only put down a $2,000 deposit on our visas, there was another $6,000 owing, so the way we figured it we had $6,000 to play with to find a way of avoiding the country.

There was a lot of debate, with our three separate groups throwing ideas across the mountains by email. Our “best idea” (and I use that term loosely) was to ship the cars through or around the country. We had to get our atlases out, but one option was to drive to Vladivostok, Russia’s icy eastern port, and get a ferry from there to the northern part of South Korea. We could then drive down the Korean peninsula to the southern port of Pusan where we would get a cargo ship to take us around China - possibly to Singapore. From there we could drive north through Malaysia and Thailand, and east into Cambodia.

Crazy.

The other option was to drive to Ulaanbaatar, the Mongolian capital, and try to get the cars onto a freight train to take them through China, possibly to Bangkok, Thailand, or Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam.

Mental.

Both options meant taking on the challenging drive to the north-east of Asia a month later than originally planned. The weather was closing in, it was already freezing in Bishkek, and it would mean tackling snow and ice, which we hadn’t anticipated. The area was also the most isolated part of the trip, a terrible place to break down, and if we went through Mongolia there would be few roads. We could also end up spending a couple of weeks at sea.

A third option was to try and get the cars shipped straight from Bishkek to Bangkok.

With these hazy, half-formed plans we began to get in touch with shipping companies. Everything was in flux and it was odd thinking that our route and our trek could be changing dramatically. Personally, I was excited. I love change, and I loved the idea that we could tackle the Chinese challenge by doing something completely ridiculous like taking to the sea with the Trabbis.

I wonder what Korea is like in November?

Megan Has Left The Building

After a week in Bishkek, Megan left us. We knew she was going, so it was no surprise, just a disappointment. We were horribly into the red, and she didn’t even have the original budget, so we always knew she wasn’t going to make it to Cambodia. She had hoped to leave from China, then Mongolia, then maybe Russia or Kazakhstan. But, as our delays increased, her point of departure shifted gradually further west until it settled gently, but uncomfortably, like an unwanted aunt on a sitting room sofa. She flew out of Bishkek early on the morning of 9 October, three months after I first met her.

Carlos, Zsofi and I stayed up late to show her to a taxi. It was a sad farewell, deep into a cold Kyrgyz night, with a few damp eyes. We tried to film the occasion, but the tape ran out at the point of departure. We waved goodbye to the cab, Zsofi continuing a forlorn flapping until the car was well out of view.

The three of us walked back arm in arm, and I felt a keen sense of loss. We hadn’t really spoken much about her going, so despite the forewarning, it still seemed a shock to see her empty bed. Zsofi must have felt the same; she took to sleeping on a mattress on the floor of the room I shared with Carlos.

Megan had been with me since my first day of Trabant Trek, 9 July, when she and Carlos greeted me at Budapest airport. We’d spent a lot of time together. While driving Fez on some endless sandy road I remember hearing her cackle and looking up to see she had taken a picture of my reflection in the rear view mirror. The photograph showed me sitting in the back, topless, in just my pants, wearing sand-smudged glasses and a hat, unconsciously pulling a face as I pored over the words on my laptop. She said it was her abiding image of me because she had seen it so often.

My image of her isn’t a still one, and couldn’t be captured by a camera. She is moving, dancing; performing a jig to conclude a short story or illustrate an episode. Thrusting her hips to a rhythm only she hears, pulling a pout and shifting her head to an imagined beat. Her feet twist, crabbing her sideways, knees bouncing off each other comically before she finishes with a flourish, hand on hip, arms and legs cocked, pulling a ridiculous mockery of a model’s stare.

It makes me laugh every time. Megan Calvert dances her own dance, and made my Trek all the brighter while she did.

Religion, Vodka And Gays

Central Asia is nominally an Islamic region. But despite extremist neighbours like the Iranians and Afghans, rarely did I notice manifestations of the faith. I don’t remember hearing the call to prayer, nor was the veil much in evidence. Perhaps the tall mountains had sheltered the region from the extremism lapping at its borders. Maybe the Soviet approach to Islam, attempting to fuse it with communist ideology, helped water down the religion’s illiberal edges. I don’t know, but although a lot of the people of Bishkek claimed to be Muslim, no rule had been abandoned more whole-heartedly than abstinence. Judging from the huge proliferation of vodka, bandied about like nuclear secrets at an Axis of Evil conference, the culprits for that imported and un-Islamic hedonism were likely to be the Russians.

In newsagents and grocery stores across the region it was quite usual to knock back a shot of vodka when picking up your morning paper. On the counter you might find a stack of grubby shot glasses, next to an open bottle of the local brew, and a plate of some sort of chaser: sliced cucumber, salted tomato, diced apple or whatever was to hand.

These “shop shots” were generally pretty huge, often seventy or eighty millilitres, cost just a few pence, and were indulged in at regular intervals by working men of all persuasions. Religion really was no boundary. I got chatting to a serious, staid-looking man with a long Muslim beard (“We Muslims do not think it right to cut your beard”) and a little Islamic cap on the back of his head - “For Allah”.

“My religion is very important to me,” he said, offering the local blessing by rubbing his hands down his face as if he were washing before going to the mosque. Then he walked into a shop for a shot of vodka.

“Isn’t it Ramadan?” I asked as I followed. I had met a man the other day who turned down water because it was daylight.

“Huh? Bah,” he washed the thought away with the fiery potion.

The effect of regularly quaffing terribly strong booze was tangible. I’m English and even I had noticed the amount of pissed shopkeepers and bus drivers. One morning I went down from our apartment to the little store to buy some eggs for an omelette. It was shortly before 10am and two men in their thirties were in the shop for a quick nip before they headed off to work. A quick nip was a giant glass of vodka, downed in one, followed by a chunk of salted tomato.

Of course, as an intrepid field agent keen to discover all I can about foreign routines, I joined the men for a drink. They laughed a lot, but I knocked back the burning paint stripper without grimacing, shook hands and left.

The result was a merry morning of high-spirited banter and easy laughter. The men seemed to be on to something so I stuck to the drink for the day and ended up in our regular nightclub, Golden Bull, where I happened upon Kyrgyzstan’s number one teen pop star, the nationally renowned singer, model and TV personality, Mikayel.

He was the club’s head of house, working the stage and occasionally showing off some rather impressive dance moves to the delight of the screaming ladies. On our first meeting he had appeared very vain, showing Carlos and me a succession of videos on his mobile phone and offering a running commentary of each: “Oh and this is the one where I do a spin. And this is the one where the girls are screaming. And this is me singing. And this is me on stage…”

It went on and on: “And this is me, and this is me, and this is me…”

I asked if we might take a picture: “Oh yes, but not here, come with me.”

He escorted us to the lobby where there was a giant poster of him, looking sultry, emblazoned with his name.

“We take it here, it is better,” Mikayel said, ushering the bouncers out of the shot.

We took a few snaps and then he insisted on looking through them.

“Oh no, not that one, that one is terrible. No delete it. No not that one. No delete it.”

“Um, ok,” I hesitated, but he watched intently to see that I did as I was told.

“Oh no and not that one. Delete it.”

“Ok.”

“And no delete. Delete… ah, there that one, good. Look at my smile. This one is the best. You may keep this one.”

“Oh, well thank you.”

It turned out that young Mikayel, who was 22, owned a stake in Golden Bull, and took me into his own private VIP suite within the club for a one-on-one interview. But his opening question caught me a little off guard: “So what is your orientation?”

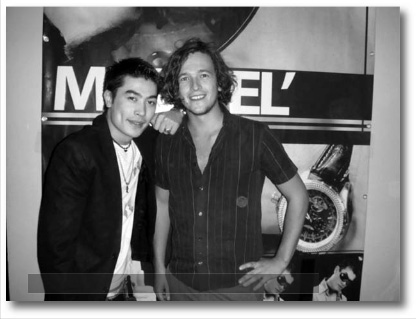

Kyrgyzstan’s favourite pop star, Mikayel, with the author

As far as I could tell we were facing north.

“No, no. Oh…” he flicked a limp hand at me, “tut, it doesn’t matter.”

Um… do you mean sexual orientation?

“Yes,” he crossed one leg tightly over the other and lent an elbow on his knee.

“Well I’m straight,” and as an afterthought, in case I had not properly bridged the language barrier, I added, “I like girls… I’m not gay.”

“Ok, ok.” Bishkek’s biggest celebrity paused to light a cigarette and eyed me. “It is just that you held my hand for so long when we met.”

“Oh, sorry. I am quite friendly…”

“What does that mean?” his eyebrow lifted.

“No, not like that. I mean I’m tactile… I’m just a friendly person.”

I was back-pedalling pathetically. There was a pause and I watched him measure me: “But you have had gay experiences?”

“Excuse me?” I tried to regain the initiative, “are you gay?”

“Oh no,” I saw him try to drop the camp inflections of his accent, “it took me a long time to persuade the media that I am not gay.”

A young boy came in, bowed in deference and carefully presented two vodka shots from a tray. My host did not acknowledge him, the lad was clearly just a serf, but Mikayel lifted his glass and looked me in the eye.

“Come, we drink. To friendship,” then quickly he added, “we only drink half,” he gestured at the midway point of the shot, raised the glass then took a quick sip. I did the same.

“Are you religious?” I asked.

“Oh yes, I am a Muslim. Islam is very important to me.”

We finished the rest of the vodka.

After my homosexual denial he seemed to lose a little interest in our interview. He kept being called out to the bar to fulfil minor obligations, while I stayed in the VIP area steadily drinking the free vodka until it was time to leave.

We met again in the club a few days later and he blanked me. Heart-breaking.

Evicted

We were told our accommodation was student digs, but I saw few students there. The residents seemed to be the down on their luck, fallen-on-hard-times types: old men with crumpled fedoras and un-ironed shirts, a woman in her thirties with a perpetual scowl and a middle-aged lady who refused to meet my eyes and ignored my daily greeting.

The courtyard was a menacing mix of old industrial waste, concrete slabs, metal pipes, bald tyres, threatening drunks and playful children. One night the beggars who lived under a curve in a pair of thick-set pipes set light to a few tyres and sat around the toxic smoke swigging vodka and shivering in their rags.

The next morning I was kicking a football about with a few kids when a man in his early thirties approached and tried to head butt me. I wasn’t sure what he was shouting and hoped he was being playful, but a kid behind him drew his finger across his throat and gestured that I should scarper.

So the following day I was a little relieved to be told by our Richter contacts that we had outstayed our welcome in their free accommodation. They explained that there was a conference taking place for nurses from all over Kyrgyzstan and our rooms had been booked up. We had been there two weeks, it seemed fair enough.

The Richter girls showed us to a pleasant, family-run hostel, full of backpackers, where there were showering facilities and a breakfast option, all for $6 a night.

I was pleased to get away from the seedy side of town, but four days later I returned to pick up some contact lenses that I had forgotten, and our rooms, the ones booked up by the nurses, stood glaringly empty.

Yurt Life

Our move to new accommodation provided a pleasing respite from the perils of over-familiarity. For the first time in months we were surrounded by new, English-speaking faces: Kiwis, Brits, French, Israelis, Hungarians, Spanish, Americans. We’d found the backpacker trail, alive with travellers’ tales: where to go, what to see, who to avoid. A wealth of facts, half-truths, misinformation, opinion and downright exaggeration channelled through the men and women who followed those strangely narrow corridors, as defined by the guidebooks that united us.

The vodka-soaked stories that accompanied our evenings were probably as close to a recreation of the old Silk Road as we would get. Israelis and French coming from China warned of pickpockets on the Xinjiang bus. Kiwis heading south to Pakistan informed us that the Khunjerab Pass would be closing in a few weeks, sealing the border for the winter. We came from the west with dark warnings of Turkmen bureaucracy and the importance of avoiding the Baku-Turkmenbashi ferry.

It must have been that way throughout Marco Polo’s time, but instead of carrying grubby backpacks the men had laden camels. Instead of gossiping into the night at hostels and guesthouses, the traders would have rested up at caravanserai, posted at intervals a day’s walk apart along many of the routes. I imagine the same spirit of banter and adventure, nurtured by the local beverage, with a few delicacies from home.

After an evening’s exuberance during the Rugby World Cup semi-final, when I made enemies of a room full of Frenchman, alienated my companions with terrifying football chants, fell in a concrete flood ditch, inexplicably broke a bathroom mirror and then accidentally left the only pub in Bishkek that shows English sport without paying the bill, I awoke with a hangover.

The Israelis made me a hot concoction of ginger, honey and lemon as a cure, a Kiwi offered me Berrocca and the Hawaiian insisted I could drink it off. With such meetings of minds does the world’s knowledge spread. Or maybe it’s the internet. Either way, the relief of new conversation helped us through our third week in Bishkek.

Initially I was sceptical about our new home. It was a yurt: a circular tent, with curved wooden props and a skin made of hides. In the top was a round hole that acted as a skylight during the day and a chimney during the evening. The hole also released any stored warmth and encouraged a stiff chill that developed as the night progressed until the small hours felt like a recurrence of the Karoo Ice Age.

Perhaps I had a romanticised notion of yurt life. Something involving nomads wandering the steppe, and pitching camp where the prey died, cooking tough mutton over the fire inside a hide covered shelter. In the morning they would wrap up and stroll down to an icy stream to fill a skin with water, then stoke the fire for a brew.

But our yurt had been set up in a back garden in one of Bishkek’s less desirable neighbourhoods. It was not a large garden, it was very obvious we were in an enclosed space, and there was a dormitory next to us where the less adventurous or more wise were staying. The nights were accompanied by the steady chorus of hounds, who only gave up at about the time that the cockerels kicked off.

I took to sleeping in a thick Russian military jacket that I’d bought in the bazaar so I could overcome the yurt’s chill, but enjoyed our new friends and the joys of access to a kitchen with a kettle.

After three months of early starts on the Trek, I fell into a strange, dreamy pattern in the unformed malaise of Bishkek. We were killing time, treading water, and for the first time since the long, lazy summer of my first year at university I had nothing to do. I was dossing. With nothing to get up for there was little to go to bed for, and I slept badly in our thin shelter, then lay in late. My day involved going into town to find a bite to eat and browse the web for news from home. Then I would find somewhere else to eat.

“Hey, I think I lost weight,” Carlos told me, plucking at the sagging waistline of his jeans.

“I think I found it,” I replied looking at my own taught paunch. Must do some exercise, I thought, for the millionth time in Bishkek.

In the evenings I might visit Metro. The bar was a tiny microcosm of the West, almost like the set of Cheers had been displaced to the heart of Asia. You could order a burger or a burrito with your Bud. Sports channels churned out American football and baseball. I couldn’t help but overhear snippets of conversation. A burly-looking American with a crew cut: “I can’t imagine anything worse than being sent to an Afghan prison. I’ve seen Afghan jails and they are frightening. Must be the worst place on earth…”

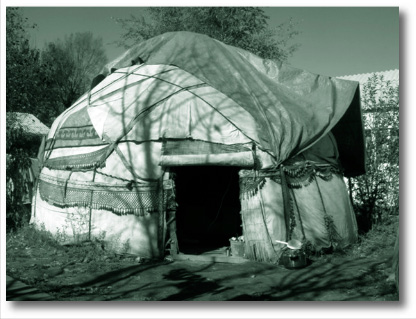

Our yurt, home for two weeks

A nerdy-looking NGO type: “…you know they’re looking for a new macro consultant at DPNG. They need someone to work in their democratisation department…”

It was a strange group of contractors, the military and charity workers, eating pizza in their little oasis.

Although not entirely frustrated by that general torpor, I was affected. I had less energy, spontaneity was dying out, a numbness had taken hold.

I managed to find a shipping company who could take the Trabants from Bishkek straight to Bangkok. They said it would take just a couple of weeks, and cost a little over $6,000. To Carlos and me, the option held a lot of appeal. It had begun to get seriously cold in Bishkek, and heading north into Siberia seemed foolhardy, if not dangerous. But no decisions could be made until Team USA had arrived. So we sat tight and waited

The Reunion

BANGKOK. It hovered in my mind like a giant, flashing out-card. We ship the Trabbis from Bishkek, straight to the Thai capital. It would take two to three weeks. While the Trabbis are en route, we meander through China, taking in a few sights, then collect the cars and continue the short trip to Cambodia.

Nice and easy, and within a month we could be on a Cambodian beach, sitting on the bonnets of our cars, warmed by the thick orange sun, sipping Buckets of Joy and telling tales of faraway places. We’d be local celebrities, and could relax, knowing we had accomplished our mission, raised a few thousand dollars, and were the first people to get three old Trabants across half the world to Cambodia.

A blissful time, running through old stories with the boys and laughing at the days when we were stuck in bleak, miserable Bishkek. Maybe spend a fortnight on the beach? I’d be home for Christmas. $6,300. That was the price of the shipping, a little more than the money we would save by skipping China and that country’s exorbitant car visas. Such a pleasant daydream.

The other option? The long northern route through Siberia, fraught with risk and danger. We drive up the length of Kazakhstan, then veer east for a thousand miles into the Siberian wilderness, before dropping south into Mongolia and Ulaanbaatar, the world’s coldest capital city.

It was the route we always planned to take, but we were six weeks late. We had imagined Siberia in autumn. We would get Siberia in winter. A time when the temperature dips below - 20c, when snow covers the half-paved roads and icy winds slash across the land.

Then the solace of Mongolia? To quote the guidebook’s advice: “We would not recommend driving in Mongolia. What appear on maps as roads are often little more than goat paths and the country has virtually no road signs.”

Perfect.

And the icing on the cake. From Ulaanbaatar we would have to ship the cars to Bangkok anyway. We just get there a month later, a month colder and a month poorer.

So there was no contest right? Right?

***

On Thursday 18 October, Team USA arrived in Bishkek. Carlos, Zsofi and I waited at a junction to greet them and guide them in. We caught sight of Dante first, with OJ at the wheel, trying to drive and change gears with one hand and operate a video camera with the other. Dante’s passenger door was still sealed shut, so I jumped in through the window and gave the big Slav a hug.

It was great to see the Yanks. It had taken them more than three weeks to cross the mountains, and now we were all together we could work out what was going on. We went straight to dinner, but it was immediately obvious that there were differences of opinion over what to do next. The boys looked knackered, Lovey seemed sullen and wasn’t eating - never a good sign.

“If we ship to Bangkok from here then that is the end of Trabant Trek,” he said.

The End of Trabant Trek.

I wonder how many times I heard that phrase. How many more times would it be uttered? “I think about fifty,” Carlos predicted.

But Lovey had a point. It was just a few days’ drive from Bangkok to Phnom Penh. Maybe give it a week to get down to the coast. Just one more week of driving.

“We’re only half way,” Lovey followed up, “so we drove half way to Cambodia and then shipped the cars the rest? That defeats the point.”

OJ chipped in: “But we’re going to ship anyway. Even if we go north to Ulaanbaatar we’re still shipping through China, so what’s the difference?”

OJ was not a big fan of going north.

Lovey: “Yes but if we ship from Mongolia then at least we have driven as far as we possibly can along the route. Then we ship because we have no choice.”

The discussion continued in this fashion as we headed back to our homestay, and a few more people revealed their positions. Tony P said he would not be shipping south no matter what and declared that he would head north on his own, without the cars if necessary.

OJ expressed concerns over the timescale. He had promised his girlfriend he would be home by the end of November and was determined not to let her down. The end of November seemed a pretty ridiculous promise to me, but I didn’t want to say. Surely she would understand? But OJ was adamant. Would it be possible to head north, ship the cars, and drive from Bangkok to Cambodia in six weeks? We worked through the route and the timing, went over the calculations, and guessed we would get to Bangkok by 5 December if we were optimistic, 15 December if we were realistic.

“So I can’t go north,” OJ said.

If we went south we would lose Tony. If we went north we would lose OJ.

Then a phone call and another bombshell. Zsofi’s father, who had lent her the money for the Trek, had heard about our situation and was withdrawing her funding. He thought Siberia would be too cold and dangerous, and shipping the cars was just ridiculous. She had about a month’s money left.

“For me this is the end of Trabant Trek,” she told us.

The End of Trabant Trek. Forty-nine to go.

Lovey said that if we were to ship the cars south he would probably go north; maybe take one Trabbi with Tony. He wasn’t definite, he wanted to be diplomatic, but he was very much in the northern camp.

Carlos was more drawn to the southern option: “Siberia is cold,” he said, “I don’t really see the point. I told my friend about all this and he said, ‘Hey, if you ship from Bishkek, you are not failures. You will have driven to Kyrgyzstan in Trabants man. And raised ten thousand dollars. That’s amazing.’”

These discussions went back and forth all night, and I fell asleep to the sound of a drunken Tony and Lovey going over the same points again and again.

***

Bangkok. In a month we could be sipping piña coladas on the beach. But it did seem too easy. Maybe it was a cop out. Surely we should drive as far as the cars, the governments, our tempers and our budgets would allow before resorting to shipping.

The more I thought about it, the more I thought I would regret not pushing on. This was an adventure and I wasn’t ready to give up. If we could find a way around China, then I would head north.

Birthday Boy

19 October was my birthday. Twenty-five. I woke up early, ate a healthy breakfast of fresh grapefruit and muesli, drank decaffeinated coffee without sugar, flossed, went for a jog, showered, removed hair from the plug hole, got a smart, respectable new look, put on clean, ironed clothes, applied for a mortgage, got a small business starter loan, and began the quest for a wife.

None of that is true, but I suppose some people think it should be. I imagine my grandfather would tell me that he had already founded and sold two newspapers by the time he was my age. My mother was raising her first child.

But times change, and my fellow trekkers, who were mostly older, seemed to have just as few tangible links to responsible society as I did. Once I entered the cycle of job, home, family and bills it seemed there would be little opportunity for gallivanting across the world until I retired from it all, in what forty years? I didn’t see the need to rush into the rat race, and I was strangely happy to celebrate my birthday in Bishkek, a city I hadn’t even heard of a few months before.

We spent the afternoon doing a clear out of the cars - stripping them and cleaning them up, redistributing the weight more evenly and trying to get organised.

They were in a pretty sorry state. Few of the doors locked or even closed, most of the tyres were old, bubbled and bald. Fez’s brakes were dodgy, we were still waiting for the front right wheel bearing to come apart irreparably, and we weren’t sure how good the new weld on the rear left control arm was. Somewhere on the drive in Kyrgyzstan, OJ drove Dante into a cow. The bovine was alright, but the cow was a little shaken up, and the front of Dante was cracked.

A new issue had reared its head. Tony called it the “sticky throttle”, and explained that the accelerator had a tendency to get stuck down. “It’s fine on the highways,” he added, “not so good in the cities.”

We drank beer and I was presented with a card and cake, which was rather touching. Then we went to a restaurant for dinner, the six trekkers plus a bunch of new friends from the hostel, before heading to Metro and on to Golden Bull, via a tense standoff with some taxi drivers following an incident related to the etiquette of urinating in bushes. When I got back I heard that OJ was locked in the toilet, asleep in his own sick. Carlos rescued him.

***

Being away from the cars for so long had given me a chance to walk. It sounds strange, but I hadn’t really walked anywhere in months. A few nights after my birthday I did the stroll from the centre of town back to the hostel. It was about three in the morning, and Bishkek was quiet. I felt calm in the ghostly silence of a sleeping city and the simple stroll gave my mind the chance to relax and wander.

Man was born to walk. As the only mammal to spend its days on two feet, it is something that defines us, that makes us human. It was the great evolutionary leap from the trees and onto our hind legs, freeing up our hands and allowing us to use tools, to build, to stroll about the savannah with a spear.

It was a mild night and I paced out a steady rhythm that my heart and lungs soon fell into time with, sending me into a meditation.

I must walk more, I thought.

I’ll file that one with “learn to dance” and “take more exercise”.

I’m only 25. Plenty of time.

The Plan: A Conclusion

The next day we got an email from the Chinese saying that they had managed to push back our visa dates by a fortnight. We stared long and hard at the route and eventually decided that we might just be able to make it to the agreed border point in time. It would be close, but it was possible.

So all the plans for shipping were abandoned, all those weeks of uncertainty brought to an abrupt halt. Living in such shifting sands, I suspect someone of a more structured persuasion would go slowly mental. But we Trekkers were used to it.

OJ agreed to come north with us; he still hoped to get home in a month, but had been persuaded to stick with us and see how it went.

Zsofi decided to go against her father’s warning and stick with us too. She had enough money to get to China, but she said she would no longer be contributing towards the $6,000 for car permits in the country. This caused a little consternation, as it meant more costs for the rest of us, but we didn’t argue.

A guy called Horst Meinecke had been following the blogs, and he’d lived in Mongolia for three years, so he sent me an email full of advice including this promising snippet: “… there will be hardly anyone to render assistance. No tow trucks, mechanics, spare parts, or people around. People die that way in Mongolia. We always had an emergency bottle of vodka in the glove compartment of our Mitsubishi Pajero, but in a serious situation, that would tide you over only for a few hours, but at least you fall asleep for the last time happy.”

How reassuring.

We got prepared for the freezing conditions ahead by stocking up on jackets, thermals and blankets at the market. We bought gloves and quilts and thick socks, even some wool to insulate the cars with. We managed to barter some new tools and a power pack from a Swiss couple in exchange for some old guidebooks. On a rare warm day in Bishkek we completely stripped and cleaned out the cars, then repacked them with the new insulation.

A month behind schedule, and down to three cars and six trekkers, we were getting on the road again. We were heading north, onto the vast, icy Siberian plateau. We were taking the Northern Route.