Epilogue

“Come to Cambodia, he said. We’ll have a good time, he said. We’ll be home for Christmas, he said.”

A favourite ditty of The Mighty Tony Perez.

Sihanoukville

If I lived in a place like Sihanoukville, I’d be smiling too. It was pretty much paradise and the locals’ natural expression was a wide, toothy grin.

But we were firmly in tourist land. Where people used to help us out of genuine kindness and hospitality, now they just saw dollar signs. It was an unwelcome but understandable shift.

There were plenty of Westerners out there, searching for the dream. I met a couple of English guys who were running a beach bar called Zion’s Den. The premises were empty when they found it, so they just moved in and bought some booze from the supermarket to flog. They lived and slept there, “Like squatter’s rights,” they said.

They were all wasted most of the time, and in fact the sanest member of staff seemed to be the dog, Zion, a beautiful little Andrex puppy who could attract the coos of the most hardened traveller.

“Did you find the dog on the beach?” I asked innocently.

“Nah, man. We got her free with some acid.”

Fair enough.

We Trekkers had become a family, but a terribly dysfunctional family. I hadn’t exchanged more than a couple of words with Lovey since our falling out. While on the road, you couldn’t really afford to fall out with anyone; you knew you were with them for the long haul. But the end of the Trek had severed those bonds. The incident didn’t affect my relationship with Tony or OJ. In fact, sitting on the beach, talking about old times, we realised we’d never had an argument.

There was a lot of sitting around on the beach. We were minor celebrities; most people had seen the cars parked up outside Monkey Republic and wondered who they belonged to. And we had a story that was far better than most of the other travellers, so at least our answers to the Sacred Three Questions of Backpacking were vaguely interesting.

“Where You From?”

England.

“Where’ve You Been?”

We drove here from Germany.

“And Where You Going… what? You drove here from Germany?”

That normally wiped the complacency off the face of the half-hearted, unoriginal plebeian who claimed to give a toss about my itinerary.

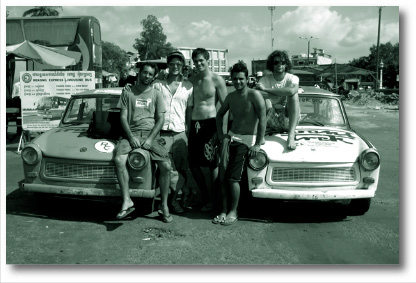

The last five trekkers who made it to Cambodia, (l-r) Carlos, Dan, OJ, Tony and Lovey

Most people expressed genuine amazement when we showed them the route map on a flier, and it did give me a sense of pride. I’d tell a few stories - stuck in the Gobi, trying to cross the Pamirs, Turkmenistan - and it was clear that what we did was pretty far from most people’s ideas of travelling. It had been funny to follow the slow shift in people’s reactions from “you’ll never make it” via “I can’t believe you’ve made it this far” to “I can’t believe you did it”.

We did a rough estimate and reckon we broke down more than 300 times - an average of twice a day, for six months. A stunning achievement, and I genuinely think it helped me to become a more patient person (either that or brain dead to delays).

I told our story to a British guy at Zion’s Den. “Travelling overland like that must give you a real sense of distance,” he said, “You know, you can step on a plane and be here in fourteen hours. But driving here. Then you really get to understand the scale of things.”

I hadn’t really thought about it before, but he was absolutely right. Going overland you get a feel for the size and shape of Eurasia, its bumps, dips, puddles and curves. But, oddly, the landmass felt far smaller to me than it did when we set off. I could look over large sections of the map and recognise the pitfalls, potential hazards, things that might slow you down and places you could race through. Having crossed deserts, mountains and forests, cities, seas and tundra, nowhere felt remote anymore.

“Slovenia? Hop in I’ll give you a ride. It’s only a week in that direction.”

And I used to bitch about picking my mates up from across town.

Although the world had shrunk since I set off on the Trek, the trip also gave me a feel for how people travelled before cars. I know what it’s like to spend a week trying to cross a mountain range, or pack the wagon with the knowledge that there won’t be any supplies en route for a few days. I know the awkwardness of stumbling about in the dark in a tiny hamlet trying to beg a place to stay and something to eat, or waving down passers-by to ask for a lift into town.

I had often wondered whether the world was being homogenised by the forces of progress and globalisation. But on my journey I realised that people are probably as polarised as ever. The differences between the way of life I’m used to and some of the ones we experienced are huge, so much so that the Tajikistan I visited was probably more different to me than to Marco Polo when he arrived 700 years before. The bustling, congested streets of London couldn’t be further from the rutted donkey trails of the Tajiks. My mod-con-filled home, my electronic gadgets and my way of urban living would be bewilderingly unrecognisable to some of the old men we met living with their entire family in Mongol gers.

People always ask me what the best parts of the Trek were. There were many, some man-made like Budapest or Beijing, some natural like the Pamirs or Gobi. But for me, the main highlight was the hospitality of strangers. It sounds corny, but I was genuinely struck by how many people went out of their way to help us. People who gave us a tow, helped find a part, gave us a push start, provided food or a bed, acted as translator, forgave our misdemeanours or pointed us in the right direction. They must number in their hundreds, the people whose acts of genuine and selfless kindness made the whole Trek work.

Tim Slessor, who in the 1950s was part of the first expedition ever to drive from London to Singapore, pointed out to me that he drove back again after- wards. Not a chance. Although I can honestly say I never felt like quitting, and I’d do it all again, road trips are off my agenda for a while.

We Trekkers gradually returned to our lives. Carlos headed to North America before returning to Barcelona, via a weekend in London. Tony, OJ and Lovey relaxed in South East Asia for another few months.

I was determined to sit still for a while, and stayed in Cambodia for four weeks. I got back to England on 5 February 2008, seven months after setting off.

Home for Christmas? I was only six weeks late.

The cars would never make it home. None of us know what has happened to Dante, though I wouldn’t be too surprised to find him fixed up and trawling the roads of northern Laos. Fez didn’t make it much further. The Americans dumped him near the Cambodian border after a failed attempt to get back to Bangkok a few weeks after I left. OJ saw a Cambodian farmer eyeing up the little East German, and thinks he may well have been converted into a plough.

A few weeks after Fez’s demise, Ziggy blew two tyres on the way to the beach. Tony and OJ didn’t have the tools to repair the car and were forced to abandon him on the side of the road. The pair had to fly home before they could rescue old Ziggy, so they left the keys with a friend in Sihanoukville. But by the time the rescue party had arrived Ziggy had already been raided by bandits, the engine stolen and spirited away. Who would steal a Trabant engine? I guess it is a mark of how far the Trabbis were from home - far enough to escape their woeful reputation. Tony tells me Ziggy was towed to a secret location to await our return.

Though the paintwork will fade, the plastic wont rust, and it’s entirely conceivable that Fez, Dante and Ziggy will hang out in South East Asia for years to come, curious locals wondering where the odd little cars have come from. But who would ever guess what those Trabants had been through for their retirement in the sun?