The story of Abelard and Heloise is, in the first instance, a story of tragic love, one so firmly established in the canon of such stories that its contours are familiar even to those who may not recognize the names. The stormy, charismatic instructor; his brilliant, unconventional student; the explosion of sexual passion and the radical act of violence that alters their lives forever; the decades of separation and inconsolable longing—who does not know that story in some form? Yet like every story of actual individuals, theirs has more than one dimension. It is also a story of fierce intellectual passion, of the commitment to reason and to the ideals of the philosophical life; a story of the conflicting logics of celebrity and solitude, of the tensions between the public and private person and between public and private ambitions. It is a story, too, of identity formation, of a struggle for a certain kind of self-definition and of the limits beyond which self-definition cannot go. It becomes a story also of making-do, of carrying-on, of the determination to fashion a useful life for oneself under trying and disappointing circumstances; a story of absence and remarkable endurance. To no small degree, it is a story of complex ego projection—of each of the pair onto the other, of both of them onto themselves, and of nearly 900 years of readers and scholars onto Abelard and Heloise together. For some, it is a story of sin and redemption.

To any version of the story, the writings of Abelard and Heloise must be central, and in particular their famous correspondence. More than raw data for the story, these writings are part of the story themselves. Abelard and Heloise were both renowned as creatures of the written word well before they ever met, Abelard as a teacher and philosopher, Heloise as the most learned woman in the France of her time, versed in Hebrew and Greek as well as the Latin classics. The habits of high literacy were woven into the fabric of their lives. A good part of their earliest relationship, they both tell us, revolved around their reading and their writing, and by the time they came to write their extant letters, their writing had assumed an even more urgent role than it had before. The defining events of their lives—their tumultuous love affair and marriage, his brutal castration at the hands of her kinsmen, and their subsequent entrance into religious orders—had taken place perhaps as long as fifteen years earlier; Heloise was now abbess of the convent of the Paraclete on the banks of the Ardusson River in the countryside near Troyes, while Abelard was some 350 miles away, the reformist head of a rebellious monastery in Brittany and, ever the magnet for calamity, under constant threat of assassination. Under the conditions of this complex separation—in space, time, and circumstance—only one way remained open to them as a recompense for other absences: their entire relationship, the obligations each had to the other, to the past they had in common, and to a future each hoped very differently to define, all now had to be matters for the written word. The letters became events in a continuing story, intentional acts of serious consequence with a public as well as a private function. Abelard and Heloise wrote from the justified conviction that their writing mattered, and to more than themselves alone; Heloise in particular often wrote as if the world depended on each sentence. Few works in Latin literature approach the urgency of these letters, their poignancy, or sense of personal drama. Few project more vivid, complex voices. Few works are more scandalous and frank, yet remain as strictly disciplined by a hard intellectual rigor. None was written as part of a more compelling story.

ABELARD IN THE CALAMITIES

Abelard tells his own story in the Calamities. It is in fact the chief source for the events of his life throughout the early 1130s, a vivid memoir of his rise to prominence as the foremost European philosopher of the twelfth century and the most charismatic teacher since the end of the ancient world, and also of the appalling set of adversities he faced.1 The traditional Latin title of the work, Historia Calamitatum, was not assigned by Abelard himself but dates from the fourteenth century, deriving from the phrase “history of my calamities” in the last section as an apt description of its contents. In form, the Calamities is couched as a letter of consolation to an unnamed and almost certainly fictitious friend, who provides a rhetorical pretext for an account of Abelard’s life. Its truer purpose and intended audience, however, may be surmised from the circumstances surrounding its composition. The Calamities was written around 1132 or 1133—the earliest possible date is provided by its reference to the papal charter granted to the nuns of the Paraclete in November, 1131—while Abelard was living in Brittany as abbot of the monastery of St. Gildas of Rhuys under the dangerous conditions the memoir describes. By 1136 at the latest, however, he was reestablished as a teacher in Paris. It is reasonable to see the Calamities, then, as part of a successful campaign of public rehabilitation, with different segments of Abelard’s audience needing assurance on different points of his extremely checkered past. This at least explains much of what may seem inconsistent in the letter, the remarkable range of distinct tones and poses Abelard assumes throughout the work—now repentant and reformed, now unreconstructed and gleefully defiant, now defensive, now triumphant, now maudlin and self-pitying, now just trying to set the record straight—as well as the shifting causes he posits for events, and the shifting moral lessons he would have the reader draw from the example of his life.

The letter presents both an offense and a defense. On the one hand, it offers continual reminders of Abelard’s well-known intellectual powers, his success with students, and the support he could expect to receive in certain secular and ecclesiastical quarters. On the other hand, it rebuts specific charges that had been laid against him. The charge of habitual womanizing in his earlier life Abelard flatly denies; the charge of taking up teaching under possibly inappropriate circumstances as a monk he answers on the simple grounds that he was forced to it, by the insistence of others in one case and by dire poverty in another. For the rest, he defends himself by pointing to the misunderstanding, ignorance, incompetence, or envy and malice of others. The Calamities proceeds episodically, then, from Abelard’s first entrance into the field of philosophy. It recounts his difficult relations with his teachers, William of Champeaux and Anselm of Laon; his establishment as a teacher himself at the cathedral school in Paris; his affair with Heloise, their marriage, and his castration; his troubles at the abbey of St. Denis and his first resumption of teaching as a monk; his condemnation at the Council of Soissons; his further troubles at St. Denis, foundation of the hermitage of the Paraclete, and second resumption of teaching; the continual attacks by “a pair of new apostles,” Norbert of Xanten and Bernard of Clairvaux; his subsequent retreat to St. Gildas; his refoundation of the Paraclete as a convent of nuns under Heloise’s direction and the further attacks on him that it occasioned. By the end of the story, Abelard is in desperate straits, “a vagabond and fugitive on the earth, … tormented without end,” and in constant fear for his life, but nonetheless resigned to the will of God. Throughout all the cycles of these disasters, only in his early relationship with Heloise does Abelard depict himself as significantly at fault.

As a memoir and a narrative that seeks to reveal some order in a life, the Calamities is certainly a rich, compelling work. Some of its undoubted power stems from the very narrowness of its focus. Great social, political, and intellectual movements—even those in which Abelard himself played considerable roles—exist only as dim background or at most emerge in the form of personal encounters with individual antagonists or supporters, most of whom remain unnamed. The focus stays on Abelard himself and the particular pattern of his interaction with the world, what he calls “the string of my calamities, which has continued unbroken until the present day.” Yet, for all its personal focus and straightforward narrative vigor, the Calamities has little of the penetrating self-analysis or confidence in life’s direction found in other memoirs—most notably the Confessions of Augustine—which Abelard could have taken up as models if he had wished. Only rarely does he show much critical self-awareness, and readers may be struck by the unattractive figure he often cuts in his own pages. To a certain extent, I think, this is deliberate and in places even overdone, as perhaps it is in his account of the affair with Heloise, where he, Heloise, and Fulbert are temporarily cast as stock characters in a farce: the cunning, cold seducer; the young innocent; and the poor, deluded cuckold, butt of jokes. Here, the motive is in part protective, I suspect—for Abelard to take all the moral burden on himself and shield, to the extent he can, the now widely respected abbess of the Paraclete—and also in part justificatory—to magnify the crime to the proportions of its punishment. But in general it is hard to account for Abelard’s repeated assertions of his brilliance and repeated displays of his supreme self-confidence as anything but ingrained parts of Abelard himself and integral to the fabric of his story.

Vanity and its comeuppance are surely not adequate terms for the pattern Abelard describes. There are gifted individuals in every field who are notoriously aware of their own gifts, individuals of enormous originality, talent, and achievement whose high opinion of themselves is well deserved. They also may be charismatic individuals, who easily inspire fierce loyalty among a following and as fierce an enmity among others. The enmity in fact can be essential to the way such people exist in the world—a way that is not always of their choosing—part of a dynamic of self-realization, in which scenes of confrontation are repeatedly enacted as means by which the self is then repeatedly enforced. The great tragic paradigms of Prometheus or Socrates come to mind, but there is no need to invoke them in order to understand the company Peter Abelard is in; scores of memoirs point to the same dynamic. Arrogance and one-upmanship are endemic human diseases, and so, too, are envy and resentment; and any may be played out against a background of larger, though still shadowy, forces. When the dynamic of self-realization spins out of control, when its stakes become critical, how can one distinguish among these factors and point to one as the single cause? The question is as pertinent to Abelard’s Calamities as it was in the matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer, the great atomic physicist whose fall from public grace became a cause célèbre in the depths of the Cold War.

The Calamities does not work progressively to a single narrative goal but rather in cycles through series of repetitions, small and large. Any resolution the narrative seems to establish quickly proves illusory. “At last I reached Paris,” Abelard says with an air of finality early in the work, but he is forced to leave the city and in fact leaves several times. Later, and again with an air of finality: “So after a few days, I returned to Paris, back to the school which had long been destined for me, which had once been offered to me, and from which I had at first been expelled.” Much of the motion of the first part of the Calamities consists of such inconclusive repetitions—to and from Paris, to and from Brittany, the shuffling of positions in the schools and in the town, virtually identical encounters with teachers and fellow students, the pattern of obstruction and overcoming, of others’ hostility and his own greatness—all driven by envy, ambition, and political machination. The explanations themselves become a kind of mantra: “As my reputation grew, so other men’s envy was kindled against me”; “His naked envy in fact won me wide support”; “But the more openly that man’s malice hounded me, the more it confirmed my own stature”; “Persecution only added to my fame.” Such a series could well go on indefinitely, or at least there is nothing in the nature of events or in the dynamic of self-realization itself to preclude such an extension.

All this appears to change, however, as Abelard approaches the affair with Heloise and the catastrophic event in his life that was, by its nature, irreversible and therefore unrepeatable—his castration. Just at what seems the culmination of his triumph, the narrative focus shifts to include a more general view and a different moral basis for events; at the same time, there is suddenly a new structure and a new meaning posited for the story:

But success always puffs up the fool; worldly ease saps the strength of the mind and soon destroys it through the lures of the flesh. Now I thought I was the only philosopher in the world and had nothing to fear from anyone, and now I began to give free rein to my lust…. As I was weighed down by lechery and pride, the grace of God brought me relief from both … : first from my lechery, by cutting from me the means I used to practice it, and then from the pride born of my learning … by humbling me with the burning of the book of which I was most proud…. I had no dealings with common whores…. So fickle Fortune, as she’s called, found a better way to seduce me and knock me down from my lofty perch—or perhaps it is better to say, for all my pride and blindness to the grace held out before me, God’s mercy brought me low and claimed me for his own.

Abelard’s castration, understandably enough, becomes a crisis, a point around which all of his life can be more neatly organized into a before and after, presented here in the traditional formulas of pride and fall, sin and grace. It also becomes a constant standard of reference throughout the rest of the Calamities, but in an unusual way. The castration is a unique event—in its violence, in its irreversibility, in Abelard’s accepting at least some moral responsibility for it—but set against the calamities to come, it is consistently downplayed, as if negated or denied. Each new calamity, Abelard insists, was certainly far worse: “I set what I had suffered in my body against what I was suffering now…. That other betrayal seemed nothing next to this, far less painful that wound to my body than this to my reputation”; “My earlier troubles seemed nothing to me now”; “I suffer more from the cost to my reputation than the loss to my body.” Even the pain from a fall from his horse, he says, “was far greater and more debilitating.”

As the castration—at least in this one way—fades from sight, so too does the moral mechanism of divine punishment and, along with it, the narrative shape it temporarily imposes on the work. Abelard was to be punished for two things, as he saw it, his lechery and his pride, the latter by the burning of his book at the Council of Soissons. By the time he comes to describe the council, though, this perspective has entirely disappeared. He is forced to burn his book in a symbolic repetition of the literally unrepeatable castration, the formidable philosopher unmanned, cut down to the status of a prepubescent child, “the merest schoolboy,” as he says. And behind this rank injustice, he insists, again lay the connivance of political ambition and the envy and incompetence of others. Immediately after the account of his castration, in fact, the whole earlier dynamic of repeated confrontation, repressed for an instant, returns with greater, even accelerating, force. Each new confrontation becomes more charged, each new iteration of calamity more perilous and insidious than the last. The return of such a structure of obsessive repetition means, among other things, that the true narrative crisis of the Calamities is always impending, never past, that no single episode will ever be definitive, but that, whatever conditions prevail at the start of any episode, they will remain recoverable in the next.

In his letters to Heloise written after the Calamities, Abelard insists that his situation at St. Gildas was at a point of crisis, the greatest he had faced. It became another crisis he was able to survive. He returned to Paris, resumed his teaching, and became a fountainhead of logic for yet another generation of students. But the pattern he describes in the Calamities survived as well. Within a few years, some new antagonists arose—“twisted men who twist all things,” he calls them in his Confession of Faith—who were to bring about a new calamity. This time, however, there would be no further episode; Abelard died before he could recover.

In 1140, Abelard was charged with heresy by a no less formidable opponent than Bernard of Clairvaux. Although the charges were to be debated openly at a Church council scheduled for the town of Sens, Bernard met privately with the assembled bishops the evening before the council convened, read out the supposed heresies one by one, and had the bishops condemn them by reciting in unison, “Damnamus—We condemn it”—after each: when Abelard appeared before the council the next day, he would be faced—as he had been nineteen years earlier at Soissons—with a fait accompli. A bitter account of the proceedings by Berengar of Poitiers, one of Abelard’s most partisan adherents, describes the evening meeting as a drunken affair, in which the sodden bishops could only mumble, “’Namus—We’re aswim”—over their cups.2 In the morning, Abelard maneuvered to avoid Bernard’s trap: rather than debate propositions that had already been privately condemned, he abruptly announced an appeal to the pope and left the assembly for Rome.

He got no further south than Burgundy, however, where the abbot of the great monastery of Cluny, Peter the Venerable, persuaded him to stay. An appeal to the pope was no longer possible: Innocent II had condemned Abelard’s teaching within six weeks of the council’s close, excommunicating him and ordering his books to be burned “wherever they might be found.” Peter’s diplomacy arranged for the excommunication to be lifted—the ban on Abelard’s books was never rescinded, though it was widely ignored—and for Abelard to remain under the protection of Cluny. In an exchange of letters with Heloise after Abelard’s death, Peter describes—perhaps with more tact than strict truth—the philosopher’s final years as a model of Christian fortitude. Abelard died on April 21, 1142, and was buried at the Cluniac priory of St. Marcellus near Chalon-sur-Saône. In a striking act of humanity and homage, Peter had the body disinterred and escorted it himself to Heloise at the Paraclete, where Abelard had long desired to rest.

HELOISE

Heloise has no analogous story, offered either by herself or anyone else. Evidence for the details of her external life is in fact so scarce that it is very difficult to imagine a narrative biography that is not merely a pendant to Abelard’s Calamities, subordinating her existence to his in memory as strictly as she herself ever sought to do in life.3 No wonder that even her most fervent admirers have tended to treat her as an emblem of some sort, perhaps an exalted but still a simplified device whose meaning resides elsewhere. To Jean de Meun and François Villon, she was la belle Héloïse, la bonne Héloïse, la très sage Héloïse. To the anonymous poet of the twelfth-century “Metamorphosis of Bishop Golias,” she figured as the bride Philology.4 On bumper stickers of the 1960s, she took on the whole burden of beleaguered womankind—ABELARD NEVER REALLY LOVED HELOISE. Perhaps most notorious—because so perversely well-intentioned—is Henry Adams’ characterization of her in his chapter on Abelard in Mont Saint Michel and Chartres:

The twelfth century, with all its sparkle, would be dull without Abélard and Héloïse. With infinite regret, Héloïse must be left out of the story, because she was not a philosopher or a poet or an artist, but only a Frenchwoman to the last millimetre 5 of her shadow.5

Even in the Calamities her name is mentioned only twice, and with such near-perfect symmetry in the narrative that a reader may suspect a symbolic purpose.6 Both times, she seems merely called into the story to resolve some external impasse to Abelard’s desires and to become the passive object of his interest—his lust in one instance, his charity in the other. But this is not how she remains. When, against all expectations, she opposes Abelard’s wishes and argues vehemently and cogently against his proposal of marriage, the independence she always possessed becomes unmistakable.

When Heloise became Abelard’s student, she was already a mature and formidable woman, in her mid- or late twenties at the time and famous throughout France for her learning.7 This is what first brought her to Abelard’s attention and to the notice of Peter the Venerable as far away as Burgundy. Learning was her most salient and stable characteristic and, I think, reveals more of Heloise as an intellectual, moral, and social being than even her love for Abelard can—a scholar “to the last millimetre of her shadow.” To judge from her quotations and allusions, she was especially well versed in the works of Jerome, Augustine, Ovid, Virgil, and the Stoic writers Seneca, Lucan, Persius, and Cicero, though it is unlikely that Heloise would have identified a separate Stoic current in the stream of ancient thought—to her, as to others of her time, they were “philosophers”—but this only makes the Stoic exemplum more potent and pervasive.8 From her reading in general, she derived, as all readers must, a reservoir of precedents and possibilities with which to conceive and represent the world and a notion of a large intellectual culture of which she could see herself a part. From the Stoics in particular, she developed a more specific set of attitudes and ideas and a certain cast of mind that remained with her, at least as far as anyone can see, throughout her life.

There is, first a distinctive style of behavior, or a style at least of the verbal behavior recoverable in the record. Throughout her writing, Heloise tended to cast herself in a series of roles originated by the heroines of her classical reading—Lucan’s Cornelia, Virgil’s Eurydice and Dido, the abandoned women of myth in Ovid’s Heroides, and even Jerome’s Paula—taking their words and gestures for herself.9 It is less learned imitation, though, than performance. From the Stoics of her reading, Heloise took up an appreciation for a kind of self-dramatization, a self displayed in a public theater through physical or verbal gestures that irresistably command attention. What may strike some as stagey or operatic is in fact a mode endorsed by Stoic writers as an appropriate and effective means of moral communication, the establishment of a paradigmatic self. When Heloise takes the veil as a nun at Argenteuil, it is with a solemn theatrical grandeur, underscored by her quotation of Pompey’s wife in Lucan’s Pharsalia, as Abelard reports it in the Calamities:

I remember many people tried to stop her … but they could not. Through her tears and sobs the best she could, she broke into Cornelia’s great lament:

O my husband,

Too great for such a wife, had Fortune power

Even over you? The guilt was mine

For this disastrous marriage. Now claim your due,

And I will freely pay.

And with these words, she rushed to the altar, snatched up the veil which the bishop had just blessed, and bound herself to the convent in the presence of all.

When she offers her argument against marriage, her theatrical posture comes across even in the indirect speech of Abelard’s report, as she begins:

And, she asked, is this how she would be remembered, as the woman who brought my name to ruin and shamed us both? What toll should the world exact from her if she robbed it of its great light? Could I even imagine what would follow this marriage—the censure and abuse, the tears of the philosophers, and the loss to the Church? What a pity it would be for me, whom nature had created for all mankind, now to become the property of a single woman—could I ever submit to this indignity? She rejected this marriage without qualification: it would be infamous and odious to me in every way.

And then, in direct speech:

she brought her case to a close in tears and sighs. “There is only one thing left for us,” she said, “that in our utter ruin the pain to come will be no less than the love that has gone before.”

This, of course, is Abelard’s report some fifteen years after the event. But the tones and rhythms of speech—even the words—are so consistent with the Heloise of the later letters as to make it likely that he is quoting from a letter written at the time, despite his claim that he heard these words from Heloise’s own mouth. In her later letters, Heloise’s performance of a paradigmatic self only reaches greater heights. Listen to part of her own great lament, composed for the Third Letter:

I am the most unhappy of all women,

I am the most unlucky of all women,

to be raised as high above them all because of you

as I am cast down low because of you,

and because of myself as well….

Has there ever been a Fortune of such extremes,

who knows no moderation in good or ill?

She made me blessed beyond others

to leave me broken beyond others,

so when I considered how much I have lost,

the grief that consumed me would be no less

than the loss that had crushed me,

and the pain that was to come would be no less

than the love that had gone before,

and the deepest of all pleasures would now end

in the deepest of all sorrows.

In the tradition of the Latin literary epistle, a letter entails a double addressee, the individual specifically named and the larger audience that will overhear. With Heloise—as with Abelard—the public side of the audience is always in mind, even when she reports what we may think would be her most intimate and private emotions: it is not some shamelessness that drives her to this language, but the controlled theatrical thrust of Stoic self-presentation. In this furious lament, it is not the self-indulgence of a Queen of the Night displayed for all to see, but the virtuosity of a Lucia Popp—but here it is Heloise performing the role of Heloise.

More significant is what Heloise derived about philosophy, for the Roman Stoics less a set of doctrines than a call to a way of life, one to which virtue was central. Heloise speaks of the philosophical life with nearly rapturous enthusiasm: the devotion to virtue, the devotion to reason—here is her passion—that she would share with Abelard. Note the thrilling tones of her words in the Calamities, again consistent with her later letters, as she tries to recall Abelard to what she sees as his mission in life:

If you care nothing for the privilege of a cleric, if you hold God’s reverence in low esteem—if nothing else, at least defend the dignity of a philosopher and control this shamelessness with self-respect.

Heloise had what in her time was a rare sense of the ancient philosophers as imitable paradigms of virtue and proper exemplars of conduct. Their lives are consistently referenced, their virtue, the rigor of their devotion, which make them proper models even for Christian monastics. This was not the notion of philosophy as conceived and conducted in the schools, the aggressive dialectical combat in which Abelard excelled and which he describes early in the Calamities. When he came to found his school at the Paraclete, however, it was on the model of the primitive philosophical community whose outlines Heloise had already sketched. But this notion of philosophy has other implications that Heloise did not hesitate to embrace. In the First Letter, she recounts an argument once put forward by Aspasia, sexual partner—or what the letter elsewhere calls “concubine or whore”—of the ancient Athenian leader Pericles, pointedly calling her “philosopher” twice in two consecutive sentences, using the rare feminine form of the noun. It was unnecessary even to bring Aspasia into the discussion, since in Heloise’s source the argument is introduced by Socrates, who in turn reports Aspasia’s words; but Heloise ignores the middleman and insists on Aspasia as the origin. A woman can be a philosopher, as we see. And a concubine or whore can be a philosopher if she devotes herself to virtue. What kind of virtue can this be?

Heloise developed from her reading an idea of the quality of the virtue that must be central to the philosophical life: it is an inner disposition divorced from outer circumstance. Throughout her writing, she consistently emphasizes the distinction between the external realm of happenings and the inner realm of intentions and motives that alone constitute an ethical condition and merit reward or punishment. The idea is not only Stoic, of course, but Heloise puts a distinct Stoic cast on all her considerations of ethical issues, and especially on the principle that ethical character does not inhere in actions but intentions, not on external circumstances but on internal disposition. Thinking of what responsibility she might have had for Abelard’s castration, she says:

I am entirely guilty; as you know,

I am entirely innocent.

For blame does not reside in the action itself

but in the disposition of the agent,

and justice does not weigh what is done

but what is in the heart

—that is, distinguishing between responsibility as a cause in the event and guilt through one’s consent to the outcome. This distinction becomes a central element in Abelard’s own ethical writings, in which he develops the doctrine of consent at length and with considerable philosophical rigor, apparently in response to Heloise’s concerns.10 And she also speaks with nothing but disdain for “those outward deeds that hypocrites do with greater zeal than any of the righteous.”

Her contempt for hypocrisy and regard only for an inner disposition seem to present a problem in the Third Letter, in which Heloise accuses herself of hypocrisy, outwardly a dutiful nun but inwardly devoted not to God but to Abelard, outwardly following the strictures of sexual restraint but inwardly only too aware of her intense sexual longings, unable to repent of what she cannot regret. But insofar as her letters are public acts, outward declarations of her inner disposition, she is no hypocrite. Heloise never retracted what she wrote in any of her letters. There is no hint of a conversion of her devotion from Abelard to God. If she remained silent about her suffering after the Third Letter, it was because it was Abelard’s order. She continued at the Paraclete doing her work for the reason she had first become a nun: because it was Abelard’s order. For over twenty years after Abelard’s death until her own death in 1163 or 1164, she remained faithful to her true vocation, the abbess of Abelard’s foundation, leading and helping others to lead the philosophical life.

THE LETTER COLLECTION

The Calamities and seven letters exchanged between Abelard and Heloise constitute a letter collection, compiled most probably at the Paraclete or at one of its daughter houses.11 The collection does not include all their correspondence, even all their correspondence with each other, but follows a specific sequence, opening with the Calamities, which both triggers the subsequent exchange and, in retrospect, provides its narrative context. In some ways, the long Seventh Letter, in which Abelard suggests a formal rule for the Paraclete, appears to form a logical end to the sequence, although there are signs at the end of the letter that an editor or compiler intended a connection with a further letter preserved only apart from the collection. The Sixth and Seventh Letters were written as a complementary pair, but there is no indication that any other letter was composed with any putative purpose of the collection as a whole in mind: the letters are what they appear to be, the sequential written responses of Abelard and Heloise to each other.

Still, the collection has an overall shape. After the Calamities, the first four letters are relatively short, relatively personal, and have an integral drama of their own, in which Abelard and Heloise reflect on their relationship, read their common history in very different ways, and seek to define two very different futures. Abelard’s castration and their entrance into monastic life had marked a new dispensation for them both, but while Abelard identified the new dispensation with divine grace and consistently pressed Heloise to be reconciled to it, Heloise saw in it little more than the exhausting prospect of a world turned upside down, of justice outraged and certainty denied, where every proper pattern might be broken, every normal sequence painfully reversed. By the beginning of the Fifth Letter, they are at an impasse, and the character of the correspondence changes. The longer Fifth, Sixth, and Seventh Letters may better be described as letter-treatises in which their personal concerns are displaced onto the institutional structures of their collaborative work at the Paraclete, and which seek in theoretical and practical terms to reconfigure the role of women in religious life.

While the authenticity of the letters has been challenged in different quarters, there remain no solid grounds for doubting that the letters are essentially the writings of Abelard and Heloise, as they appear to be.12 There are signs, however, that the texts have been retouched, either by the compiler of the collection or by reader-copyists of unknown date, who have left comments and additions that have been incorporated into the common text. In the Calamities and the earlier letters, the signs are few and very minor; in the letter-treatises, however, which engage controversial issues of wide concern to monastic life, the interpolation of later material becomes significantly more frequent and extensive. I have suggested in the translation passages that are most likely to have been added by later hands than those of Abelard and Heloise. For this, I have used continuity of argument and rhetorical structure as a criterion throughout: passages that are demonstrably out of place have been bracketed as suspect.

THE PROSE OF ABELARD AND HELOISE

Neither Abelard nor Heloise was a conversational writer, though Abelard could mimic the rhythms of conversation when he wished. Both were trained in the sophisticated modes of the learned Latin of the time and proficient in meeting its most literate expectations. Their prose has a distinctly oratorical cast, sharply conscious of the audience, large or small, for whom they were fashioning their appeals. We can see this most readily in the casual ease with which Abelard assumes the posture of a lectern speaker in, for example, the polished speech he puts into the mouth of the bishop of Chartres at the Council of Soissons in his Calamities, in his sudden address in the Sixth Letter to a male audience that cannot actually have been present—“Let me ask my brothers and my fellow monks, who every day gape after meat…”—or in a dozen other moments in the Sixth and Seventh Letters when he exhorts, admonishes, and instructs the nuns of the Paraclete. But this same oratorical cast and awareness of a public is present throughout the letters, even when they seem most private and most intimately reflective.

Speech like this must depend on the dynamics of the living voice, its energies, stress, rhythm, pace, and pauses, but here those dynamics can only be intimated by what is on the page. The prose of both Abelard and Heloise, however, is conspicuous for a tendency toward certain patterns, favored forms of repetition—of sounds, words, or concepts—that help define what is called their style and can help make their voices vivid. Chief among these, for Abelard and Heloise both, is the tendency toward formal balance, which operates in the conceptual, syntactic, and sensory dimensions of their language. In the first paragraph of the Calamities, the conceptual balance of opposing terms is most evident:

The force of example often does more than words to stir our human passions or to still them. With this in mind, I have decided to follow up the words of consolation I offered you while we were together and write an account of my own experience of calamities to console you while we are apart. I expect you will see that your trials are only slight next to mine, or even nothing at all, and then you will find them easier to bear.

“Example” is opposed to “words,” “stirring passions” opposed to “stilling” them, and further oppositions follow: together/apart, your trials/mine, slight/nothing at all—the regular pulse of these oppositions creates the basic rhythm of the lines. In other places, syntactic balance, especially the use of correlative clauses (tam … quam and tanto … quanto clauses in Latin), often forms the primary structure of a sentence; there is an example early in the Calamities—“the more progress I made in my studies, the more passionately I devoted myself to them”—and it becomes very common throughout the letters, rising in frequency with the formality of the prose. The tendency toward balanced repetition extends also to the sensory aspects of language. Both Abelard and Heloise wrote highly rhythmical prose, marked with formalized stress cadences and phrases paired for a balanced syllable count; both also could be free with anaphora, alliteration, assonance, and even rhyme in the medieval tradition of rhymed prose. The full use of these sonic resources can create patterns of a very striking kind.

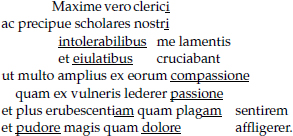

For Abelard in the Calamities, the full application is reserved for moments of special intensity. We need look only at the first sentences of his castration lament to get a sense of the possibilities; it will be best to set out the Latin in a form that highlights its verbal structure:

Mane autem facto, tota ad me civitas congregata,

quanta stuperet admiratione,

quanta se affligeret lamentatione,

quanto me clamore vexarent,

quanto planctu perturbarent,

difficile immo impossibile exprimi.

By the next morning, the entire city had converged outside my door, shocked and appalled, moaning and howling and wailing such earsplitting cries that it is hard—no, impossible—to describe it.

After the light alliteration of civitas congregata there follow four syntactically parallel phrases marked with anaphora of quanta and quanto; with the full and unstressed rhymes of stuperet and affligeret, admiratione and lamentatione, and vexarent and perturbarent; and with the paired number of syllables in the parallel phrases clamore vexarent and planctu perturbarent. The sentence ends by moving away from this block of parallels, but not before it asserts another set of opposing terms, difficile and impossibile, “hard” and “impossible.” Abelard, however, is just warming up; unfazed by what he has just called the impossibility of verbal description, he continues with more rhymes, part-rhymes, and paired phrases and words:

The clerics were the worst and my students worst among them, crucifying me with their screams and laments until I suffered more from their pity than my pain, more from chagrin than the injury itself, and more from the scandal than the scar.

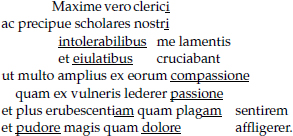

His third sentence is a grand flourish of anaphora, alliteration, assonance, and rhyme:

I thought of the glory I once enjoyed and the simple, vicious act that brought it low, the judgment of a God who struck where I most had sinned, the vindication by broken faith when I had broken faith, the exultation of my enemies over this so fitting reward, the lasting grief this wound would bring to my parents and my friends, the way my particular shame would spread throughout the universe of men. No road was now left open to me, no face I could show to the world, when every finger would point, every tongue would mock the monstrous spectacle I would become.

This sort and degree of artifice, particularly in the set of circumstances it describes, has chilled many readers for both aesthetic and psychological reasons. The novelist George Moore—no conversational writer himself—dismissed the whole passage as an interpolation in “the strained, rhetorical style of a student in rhetoric bidden to write a theme on the feelings of a man gelt in the dead of night by ruffians that a bribed servant let into the house,”13 and others have had similar reactions to what they see as its emotional inauthenticity. But the passage, we remember, was written more than a dozen years after the event, time enough for even such a powerful irritation to have developed a thick protective coating of pearl: the same artifice that signals strong emotion also signals a conscious attempt to regulate that emotion.

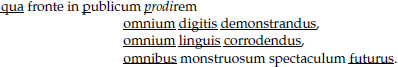

For Heloise, the techniques of sentence balance are similar but more concentrated and consistent, and with a much stronger tendency to shape phrases and sentences according to their rhythms and their sounds as well as their syntax. This patterning becomes basic to her prose. Some of her most famous utterances are in fact formed around rhymes, as this from the First Letter:

If great Augustus, ruler of the world, ever thought to honor me by making me his wife and granted me dominion over the earth, it would be dearer to me and more honorable to be called not his royal consort but your whore.

But she does not wait for the highest moments; the principle of sonic balance is evident even in her lists, as it is in the Third Letter:

[There I see] a woman before a man, a wife before a husband, a handmaid before her lord, a nun before a monk, a humble deaconess before a priest, and an abbess before an abbot.

In a shorter sentence or phrase, she often borrows word placement strategies from Latin hexameter poetry, as she does in this simple statement from the First Letter:

Solent etenim dolenti nonnullam afferre consolationem qui condolent.

A community of grief can bring some comfort to one in need of it.

Solent is first echoed in dolenti, and then both are echoed in consolationem and condolent and also amplified as if by the prefix con-. (There is an etymological relationship between dolenti and condolent but only a sonic one between solent and consolationem: Heloise does not shrink from a pun.) The sound play here reinforces another symmetry: the two finite (and rhyming) verbs solent and condolent frame the phrase with the infinitive verb afferre set between them and also between the noun consolationem and its adjective nonnullam.

In longer sequences, she uses anaphora and rhyme freely and often employs them to extend a pattern beyond a single sentence, building at times to rhetorical crescendo. From the First Letter:

You alone, after God, are the founder of this place, you alone the builder of this oratory, you alone the architect of this congregation.

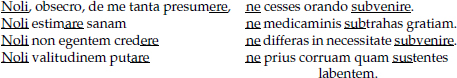

From the Third:

Do not presume so much, I beg of you: you may forget to help me with your prayers. Do not ever suppose that I am healed: you may withdraw the grace of your healing. Do not believe that I am not in need: you may put off your help when I most need it. Do not imagine that I am strong: I may collapse before you stop my fall.

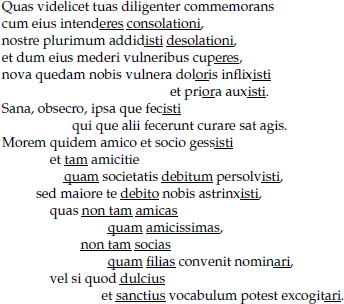

And again from the First:

But as you told of them in such detail, while your mind was on his consolation, you have worsened our own desolation; while you were treating his wounds, you have inflicted new wounds upon us and have made our old wounds bleed. I beg of you, heal these wounds you have made, who are so careful to tend the wounds made by others. You have done what you ought for a friend and comrade and have paid your debt to friendship and comradeship. But you are bound to us by a greater debt, for we are not your friends but your most loving friends, not your comrades but your daughters—yes, it is right to call us that, or even use a name more sacred and more sweet if one can be imagined.

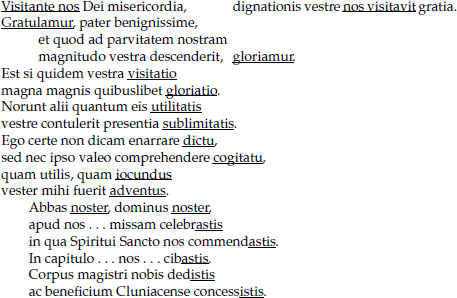

The rhythm of verbal correspondences becomes perhaps most spectacular in her most formal address, the rhymed prose of her letter to Peter the Venerable:

To us, the coming of your worthiness was the coming of God’s mercy. We are grateful, kindest father, and we glory that your greatness has descended upon us, for we are small. Indeed, your coming would be cause for glory to anyone, however great. Others know what good they may derive from the good of your high presence. I myself do not have the words to say, or even the intellect to comprehend, all the good your visit brought to us, all the personal pleasure to me. My abbot and my lord: You celebrated Mass in our presence…. You commended us to the Holy Spirit in that Mass. You feasted us in our chapter…. You restored to us the body of our master and extended to us the kindness of Cluny.

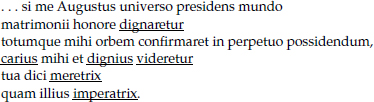

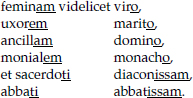

But it is in the short salutation to the First Letter that the rhythms are used to their greatest and most concentrated effect:

Domino suo |

immo patri |

coniugi suo |

immo fratri |

ancilla sua |

immo filia |

ipsius uxor |

immo soror |

Abaëlardo |

Heloïsa. |

To her lord, no, her father; to her husband, no, her brother. From his handmaid, no, his daughter; his wife, no, his sister. To Abelard from Heloise.

The apparently simple task of a salutation, to identify the sender and recipient, is revealed as a complex problem in this case: what are these two to one another? With extraordinary compression, Heloise recapitulates the categories of her history with Abelard—lovers, spouses, nun and monk, communicant and priest—alternating between the terms of their personal and ecclesiastical relationships. But as the terms proliferate, each becomes inadequate and the aggregate itself collapses of its own weight: what remains as adequate is what also remains beyond types: their proper names, individual and unique. Along with the dense, implicit argument is an equally dense set of verbal repetitions and recurring sounds, shifting patterns of rhyme and part-rhyme, carefully controlled emphasis and acceleration through the sequence of terms, with a necessary catch or pause before the final pair of words, all held in place by a near-perfect syllabic alternation of five beats to four.

William Gass, one of our finest writers and theorists of prose, once noted:

Language without rhythm, without physicality, without the undertow of that sea which once covered everything and from which the land first arose like a cautious toe—levelless language, in short, voiceless type, pissless prose—can never be artistically complete. Sentences which run on without a body have no soul. They will be felt, however conceptually well connected, however well designed by the higher bureaus of the mind, to go through our understanding like the sharp cold blade of a skate over ice.14

His point was to stress the irrational, the subliminal emotional force of such writing, and the force of such prose as Heloise wrote cannot easily be denied. But there is another, and for the moment a more important, consideration—the intellectual discipline, the emotional measure, the sheer psychological poise required to do such writing in the face of its shattering subject. For Heloise as well as Abelard, the cost of this poise, no doubt, was enormous, but it is a cost that must be borne by all those who, as Abelard and Heloise certainly did, elect to continue living their lives.

One of the fundamental aims of this translation is to respond as far as possible to the voices of Abelard and Heloise (and the other named and unnamed writers in this volume) as they shift from author to author and from circumstance to circumstance. For this, it uses a relatively formal and rhythmical English prose, although both the formality and the rhythms become lighter when the Latin text demands it. Any attempt at rhymed prose in English would of course be disastrous here, but I have tried to reflect some local effects through less assertive means—assonance, alliteration, and, very often, rhythmical correspondence. When the degree of verbal patterning in the Latin becomes especially intense—at strategic passages for Abelard but more commonly for Heloise—I have adopted the additional measure of setting out the translation in patterns perceptible to the eye, using line breaks and indentations to accommodate the pace, relative emphasis, recurring rhythms, and fabrics of verbal correspondence established in the Latin text. The introduction of these patterns in the English, of course, reflects no change in the visual arrangement of the Latin, which retains the familiar format of ordinary prose. The prose of Abelard and Heloise, however, was of an extraordinary character, and in our time it still may exert extraordinary force.

The translations are based on the following Latin texts and editions, except where indicated in the notes.

The Calamities of Peter Abelard: J. T. Muckle, “Abelard’s Letter of Consolation to a Friend (Historia Calamitatum),” Mediaeval Studies 12 (1950), 163–213.

The First–Fourth Letters: J. T. Muckle, “The Personal Letters Between Abelard and Heloise,” Mediaeval Studies 15 (1953), 47–94.

The Fifth–Sixth Letters: J. T. Muckle, “The Letter of Heloise on Religious Life and Abelard’s First Reply,” Mediaeval Studies 17 (1955), 240–81.

The Seventh Letter: T. P. McLaughlin, “Abelard’s Rule for Religious Women,” Mediaeval Studies 18 (1956), 241–92.

The Questions of Heloise: Introductory Letter: J.-P. Migne, Patrologia Latina, vol. 178, 677–78.

Abelard’s Confession of Faith: J.-P. Migne, Patrologia Latina, vol. 178, 375.

The Letters of Heloise and Peter the Venerable: Giles Constable, The Letters of Peter the Venerable (Cambridge, MA, 1967), Letters 115, 167, and 168.

“Lament of the Virgins of Israel for the Daughter of Jephtha”: J.-P. Migne, Patrologia Latina, vol. 178, 1819–20.

“Lament of David for Saul and Jonathan”: Oxford Book of Medieval Latin Verse, ed. F. J. E. Raby (Oxford, 1959), 246–50.

“How Great the Sabbath: Hymn for Saturday Vespers”: Oxford Book of Medieval Latin Verse, ed. F. J. E. Raby (Oxford, 1959), 243–44.

“Adorn the Chamber, Zion: Hymn for the Feast of the Presentation”: Oxford Book of Medieval Latin Verse, ed. F. J. E. Raby (Oxford, 1959), 244–45.

“After the Virgin’s Highest Honor: Hymn for the Night Office and Vespers”: J.-P. Migne, Patrologia Latina, vol. 178, 1812.

“Open Wide Your Eyes”: Ulrich Ernst, “Ein unbeachteres ‘Carmen figuratum’ des Petrus Abelardus,” Mittellateinishes Jahrbuch 21 (1986), 125–46.

“To Astralabe, My Son”: J. M. A. Rubingh-Bosscher, Peter Abelard, Carmen ad Astralabium: A Critical Edition (Groningen, 1987).

The Letters of Two Lovers: Ewald Könsgen, Epistolae duorum amantium. Briefe Abaelards und Heloises? Mittellateinisches Studien und Texte 8 (Leiden, 1974).

All biblical passages are quoted in, or adapted from, the Douay-Rheims translation, as revised by Richard Challoner (1749–1752), and their citation corresponds to that version.

______________________

1 Clanchy 1997 provides a fine, full biography of Abelard; Marenbon 1997, 7–35, an excellent biographical sketch.

2 For the plausibility of Berengar’s account, despite its satiric intent, see Clanchy 1997, 309.

3 McLeod 1971 does what she can with limited material, and her account remains the fullest biography of Heloise to date.

4 For the representation of Heloise in this poem, see Dronke 1976, 16–18.

5 Adams 1986, 270.

6 That is, Heloisa 2,031 words from the beginning of the work and 2,231 from the end; elsewhere she is “she,” “the girl,” or something similar.

7 For her birth around 1090 or slightly before, see Clanchy 1997, 173–74, in preference to the traditional date of 1100 or 1101 accepted by McLeod 1971, 8; Marenbon 1997, 14; and many others.

8 Ebbesen 2004, 125, says of the Stoic strain in medieval thought, “Stoicism was nowhere and everywhere in the Middle Ages—but it was everywhere in a more important sense than the one in which it was nowhere.”

9 A point well stressed by Newman 1992, 150–51.

10 Abelard’s ethical writings were composed in the mid- or late 1130s and so postdate the letters of Heloise by a few years, but the questions they address had plainly been a subject of discussion between them for some time: “as you know, I am entirely innocent,” Heloise writes in the First Letter. Ultimately, however, the issue of priority is of less moment than the fact that Heloise was an active participant in the ongoing philosophical endeavors of her time.

11 Some versions of the collection do not recognize all of the long Seventh Letter, sometimes called “The Rule for Religious Women,” which is preserved in several manuscripts as the last of the letters. In scholarly editions of Abelard’s correspondence, the Calamities is labeled Epistle I, so that what is presented in this volume as the First Letter is there labeled Epistle II, and so on. I have followed the numbering of the latest complete editions of the letters by J. T. Muckle and T. P. McLaughlin, which also seems both the most sensible and the clearest for a reader. For the genesis of the collection, see Luscombe 1988a.

The entire collection was first translated into English by Joseph Berington in 1787 and again by C. K. Scott Moncrieff in 1926. The well-known translation by Betty Radice (1974; revised by Michael Clanchy 2003) redacts and summarizes much of the difficult Sixth Letter. Several English translations of the Calamities alone have been published under various titles, most recently by Muckle 1964.

12 For a concise history of the question and a fair assessment of the arguments, see Marenbon 1997, 82–93.

13 Moore 1926, xv.

14 Gass 1985, 122.