With the approval of the revised plans for the attack, the movement of over 500,000 troops began. To maintain some semblance of secrecy, movement toward the front of combat units and concentrations of supplies took place primarily at night. In order not to attract German attention a certain level of daytime activity was maintained and increased slightly during the first week of September. While the Germans did anticipate a possible attack against the salient, their intelligence reports estimated that given the character and amount of observed traffic circulation the offensive most likely had been postponed.

The rains came early in September, drenching the men as they marched in pitch-black night toward the front and slept in the woods during the day. The rain continued over the night of September 11–12, filling the trenches at the front with water and mud and further hampering the movement of troops and supplies.

As early as September 8 American intelligence began to detect signs that a German withdrawal might be under way. A prisoner captured on September 8 reported that the narrow-gauge railroads were being removed. On September 11 aerial reconnaissance reported no hostile fire from forward German trenches, raising further suspicions. Alternatively, the radio-intelligence section reported normal German radio traffic throughout the day.

By September 10 the 89th and 90th divisions had narrowed their frontages to allow the additional units to move to the front. The combination of rain together with thousands of men and hundreds of trucks moving toward the front turned every road and path into a quagmire. Once at the front the troops were assigned to waterlogged trenches and prohibited from lighting fires or smoking. Pershing held a final meeting of all corps commanders at Ligny on September 10. Several staff recommended a delay because of the soggy ground conditions, but given the tight timetable required to get the First US Army positioned for the Meuse–Argonne offensive, Pershing rejected the suggestion.

I Corps

The American I Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. Liggett, held the easternmost portion of the line, with its right resting at Pont-à-Mousson. From east to west I Corps had the 82nd Division deployed on both banks of the Moselle, with the 90th, 5th, and 2nd divisions extending to Limey. The 78th Division was assigned as corps reserve. I Corps was directed to capture Thiaucourt and assist IV Corps in capturing the Bois d’Euvezin and Bois du Beau-Vallon.

The 2nd Division was deployed on the extreme left of the corps’ line, with the 5th Division to its right and the 89th Division from IV Corps on the left. The 3rd Brigade, composed of the 9th and 23rd regiments, was designated to lead the assault, followed by the 4th Brigade, made up of the 5th and 6th Marine regiments. The first-day objectives for the division included an initial advance of 3 miles to the first objective line at the Bois de Heiche, where it would reorganize and move almost 2 miles farther to the second objective line along a line crossing the Rupt de Mad, between Thiaucourt and Jaulny, before stopping for the night.

The 82nd Division, positioned on the easternmost flank of the American line, straddling the Moselle River, was expected to “exert pressure on and maintain contact with the enemy” and was not expected to undertake any significant offensive actions. Liggett, commanding I Corps, argued without success that the 82nd should move forward and threaten a concentration of German guns at Vittonville.

The 90th Division occupied a frontage of roughly 3 miles and formed the easternmost attack element of I Corps. The I Corps attack plans designated the 90th Division to advance in line with the 5th and 2nd divisions, while protecting the corps’ right flank. The divisional attack orders prescribed that the two brigades would deploy side by side, and that within each brigade the regiments would also be deployed in line. The entire division was expected to pivot on the right flank, with the 180th Brigade on the right merely holding its ground while the 179th Brigade advanced, keeping contact with the 5th Division on its left. The 179th Brigade was ordered to advance roughly 2 miles to reach the first-day objective.

The 5th Division, positioned between the 2nd Division and 90th Division, held a narrow front just over a mile wide. The division was directed to drive due north, capturing the ruined village of Viéville, which lay just beyond the American lines. The first German position, which included bands of barbed wire and a system of trenches, was located a half-mile beyond Regnéville near the Bois de la Rappe. The second position, almost a mile farther north, was considered the main line of resistance. Stretching through the Bois des Saulx, Grandes Portions, and St Claude, this position was composed of two trenchlines reinforced with concrete strongpoints. The Germans had also constructed deep dugouts in the woods and had deployed artillery north of the woods. Viéville had been reinforced with machine-gun positions in abandoned houses and in the steeple of a church. A German hospital and rest camp was located in the third German line, almost 2 miles beyond Viéville.

General John Lejeune and 2nd Division staff.

The American 1st Division was deployed at the western end of the American line and assigned to protect IV Corps’ left flank during the attack. German positions on Montsec provided a clear view of American deployment.

General John Pershing with Maj. Gen. Wright, commander of the 89th Division.

IV Corps

Commanded by Maj. Gen. Dickman, IV was made up of the 89th, 42nd, and 1st divisions, tied in with the French II Colonial Corps, which was positioned opposite the nose of the salient. The 3rd Division was held as corps reserve. The corps was expected to drive on St Benoît and Vigneulles and assist I Corps in capturing Thiaucourt. If I Corps was delayed then IV Corps was authorized to capture Thiaucourt.

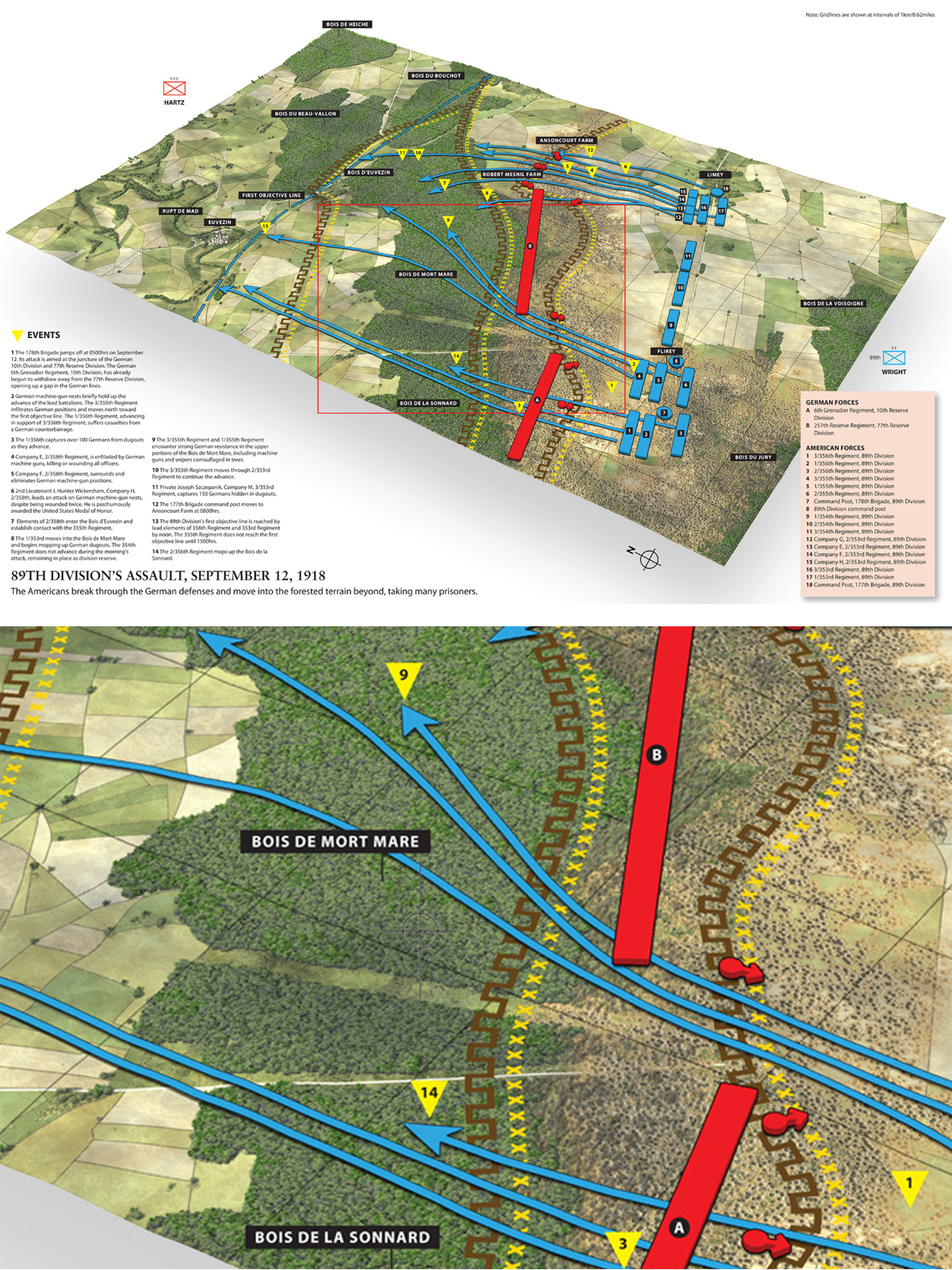

The Bois de Mort Mare and adjacent Bois de la Sonnard extended almost across the entire frontage of the 89th Division. To the east of the forest the Promenade des Moines, a bare ridge, dominated the landscape. The slope to the top of the ridge was covered with trenches and barbed wire. There were two strongpoints: Robert Mesnil Farm and Ansoncourt Farm. Extending northeast of the Bois de Mort Mare were the dense woods of the Bois d’Euvezin and Bois du Beau-Vallon. A narrow-gauge railroad traversed the Bois de Mort Mare.

Attack orders directed a general advance toward Euvezin with the intention of supporting the movement of the 42nd Division on the west and the 1st Division on the east. The 89th Division was ordered to capture Thiaucourt if the 1st Division was delayed.

Major-General Wright assumed command of the division on September 6. Wright affirmed the preliminary staff planning, which focused the main effort of the division to assist 42nd Division on the west. The 178th Brigade was deployed on the left. The 177th Brigade, less the 354th Regiment, which was designated as divisional reserve, was to support the 1st Division on the east. The 178th Brigade planned on advancing through the Bois de la Sonnard and Bois de Mort Mare, using two open corridors, each 200yds wide. The 177th Brigade would bypass the Bois de Mort Mare to the east on the first day and detach units as necessary in order to clear out any lingering resistance in the woods.

The 1st Division occupied the extreme left flank of the American line on the southern face of the salient. The 2nd Brigade (26th and 28th regiments) was deployed on the right, maintaining contact with the 42nd Division while the 1st Brigade (16th and 18th regiments) was placed on the left. The third battalions of each infantry regiment were assigned as either brigade or division reserve. Both brigades occupied a front approximately 2 miles wide and were expected to advance a little over 4 miles, capturing the Quart de Reserve and the town of Nonsard. All front-line infantry was to be accompanied by engineer detachments, equipped with Bangalore torpedoes and special bridging equipment for crossing the Rupt de Mad and Rupt de Madine. Additional specially equipped infantry units were equipped with wire-cutters. The divisional plan included four phases, each governed by a rolling artillery barrage. Each phase had a separate objective that allowed the infantry to reorganize. The barrage was scheduled to pause briefly before continuing. Premature advances beyond each objective would subject the infantry to friendly fire and once the fourth objective was reached the division was expected to consolidate its position for the night. The 1st Division advance was to be supported by 120 75mm guns and 48 155mm or 8in. howitzers. An elaborate schedule for displacing individual batteries forward to maintain the barrage was also prepared. The division was assigned 49 tanks, which were deployed along the left flank, and a detachment of cavalry.

American tanks and crews deployed for the St Mihiel attack. Patton developed a system for identifying companies using symbols such as diamonds or hearts painted on the tanks.

Brigadier-General MacArthur and staff. MacArthur commanded a brigade in the 42nd Division.

The 42nd Division moved to the front during the night of September 10–11, deploying between the 1st Division and 89th Division. The division objective was from the Bois de Dampvitoux, north of St Benoît, through the Bois de Vignette. The division deployed its regiments in line across its frontage. While the division was considered one of the most combat tested in the First US Army, the losses of the Aisne–Marne fighting earlier in the summer had depleted its ranks. Some battalions would begin the attack with replacement men and officers making up more than 50 percent of their strength.

The 26th Division was ordered to advance through the wire toward the devastated Bois Eparges. Neither the German wire nor the Bois Eparges represented a significant barrier to the initial advance of the 26th Division.

General John Pershing, center, reviewing Maj. Gen. Cameron’s 26th Division.

American tanks loaded onto railroad cars for transport to the front.

V Corps

Deployed on the western face at Les Eparges, V Corps positioned the 26th Division, the French 15th Colonial Division, and the 8th Brigade of the 4th Division. The remainder of the 4th Division was assigned as corps reserve. The corps was assigned the task of capturing the Heights of the Meuse, focusing on Les Eparges, Combres, and Amaranthe.

The 26th Division joined Maj. Gen. Cameron’s V Corps on August 28, 1918, settling into position along a 2½-mile front between the French 15th Colonial Division to the north and the 2nd Dismounted Cavalry Division to the south. The 26th Division’s objective was to secure the Heights of the Meuse and pivot to its left, bringing its right flank into line with the American units advancing from the south, and ultimately move toward the Michel Stellung.

Tank support

Patton’s final attack plans directed that his 1st Tank Brigade, with 144 Renault tanks and joined by two groups of French Schneider tanks, would be used to support the 1st Division and 42nd Division. The 327th Tank Battalion, led by Captain Ranulf Compton, would be supported by the French 14th and 17th groups and would support the 42nd Division. Major Sereno Brett’s 326th Tank Battalion would be assigned to the 1st Division. Patton also instituted an identification protocol based on the suites of playing cards. Hearts, diamonds, clubs, and spades were stenciled on white backgrounds on each tank’s turret. A number between one and five was also marked next to the symbol to identify each tank in a platoon.

As the Americans struggled through the rain to reach their jump-off positions or waited with anticipation for the attack to begin, Lt. Gen. Fuchs had already issued orders to the 10th Division and 77th Reserve Division to begin their withdrawal. He directed both divisions to fall back to the artillery protective line by 0300hrs, leaving limited forces behind to delay any American advance.

At 0100hrs, September 12, 1918, in a driving, cold rain, the first American offensive began with the firing of thousands of artillery pieces all along the St Mihiel salient. German artillery returned fire, concentrating on the American front line and strategic targets such as crossroads to the rear of the front lines. Although the German artillery fire was sporadic and largely ineffective, it did catch the ammunition supply train of the 2nd Division and inflicted severe casualties. Reports from along the line remarked that German fire was largely negligible and American counterbattery fire silenced the few German guns that attempted to reply. Colonel “Wild Bill” Donovan, a veteran of fighting along the Ourcq and Vesle rivers, understood the implication, remarking simply, “The Germans are pulling out.”

As the American artillery increased in tempo, so did the flow of men and vehicles toward the front. Tanks intended to support the 5th Division, along with an artillery ammunition train, became entangled in a massive traffic jam. Some units were safely in position by midnight but others struggled through the rain, mud, and chaos toward the front. Men from the 9th Regiment, 2nd Division, waded through thigh-deep water for almost a mile before reaching their positions. Patton’s tanks were detrained and moved slowly toward the front. In the 1st Division sector five tanks accompanied the infantry toward the Rupt de Mad while 44 others deployed on the left, crossing the stream behind American lines and moving to support the attack. American air squadrons waited impatiently throughout the night, watching the rain and listening to the artillery, unsure whether they would be released to fly in the horrible weather.

German reaction

Major-General Otto von Ledebur, Army Detachment C’s Chief of Staff, rushed to his headquarters at Conflans to piece together the details of the American attack. The American barrage had caught the 10th and 77th Reserve divisions in the process of pulling back to the artillery protective line. The German 10th Division had mixed success in withdrawing. Having deployed its artillery in deep echelon, it was able to avoid serious losses, and the bulk of the infantry also escaped the initial barrage. Conversely, the commander of the 77th Reserve Division delayed the withdrawal of his artillery, resulting in the destruction of the bulk of the guns. Ignoring orders to reduce the number of men deployed in forward positions, the 77th Reserve Division was caught with nearly two-thirds of its men in the front lines.

An American ammunition truck being camouflaged. The use of camouflage had become widespread by both the Allies and Germans by 1918. Intricate patterns were used on vehicles, airplanes, and artillery. The Germans also pioneered the use of camouflage on helmets.

Lieutenant-General Fuchs correctly concluded that the strong American artillery barrage heralded an attack against the southern face of the salient. At 0130hrs, without authority from Supreme Headquarters, he directed the 123rd and 31st divisions, deployed in reserve, to concentrate north of Charey and around Gorze. Fearing the worst, he also notified the 88th Division to move to Allamont and the 107th Division to move to Buzy. Fuchs was later given command of the 255th Division deployed along the Moselle.

IV Corps

At 0500hrs the artillery shifted back toward the German front-line positions, and along the southern face of the salient whistles sounded as the Americans rose up and advanced. With their appearance, multicolored flares rose over the German positions.

On the far left of the southern face of the salient, under the unflinching gaze of Montsec, the 1st Division moved out, each front-line platoon accompanied by sections of engineers equipped with wire-cutters or Bangalore tubes to open paths through the German wire. In addition, other engineer details carried bridging equipment to cross the Rupt de Mad. On the division’s extreme left the 18th Regiment deployed two battalions in line and was supported by tanks and a provisional squadron of the 2nd Cavalry. The 16th, 28th, and 26th regiments extended the 1st Division line to the east. Following the barrage the 1st Division paused briefly at its first objective, the southern bank of the Rupt de Mad, before splashing across the creek and moving toward the ruins of Richecourt and past its second objective. Pushing past feeble German resistance in Richecourt, they continued through Lahayville toward the third objective line; as they neared the southern edge of the Quart de Reserve the woods became alive with German machine-gun fire. Supported by tanks, the infantry rushed through the improvised barbed wire, capturing or killing the defenders.

The 1st Division advancing under the shadow of Montsec. Montsec dominated the St Mihiel battlefield, allowing German observers to monitor the movements of American troops along the southern face of the salient.

American infantry and tanks advance near Seicheprey. American troops had been assigned around the Seicheprey area since the spring of 1918. In April 1918 the Germans launched a major raid on 1/102nd Regiment of the American 26th Division, capturing 187 men and killing 81. The raid was a major embarrassment for the Americans, and set back General Pershing’s attempts to organize an independent American army.

Earlier in the morning Patton had reported to IV Corps headquarters from his observation point, a hill northwest of Seicheprey, that only five of his tanks were out of action. In reality Compton’s 325th Battalion had only 25 tanks actively engaged; 23 were out of action because of mechanical failures or from being stuck in mud. Another 19 were assigned either to resupply duties or as part of the battalion reserve.

Skirting the woods where German resistance was too strong, the 1st Division reached its third objective between 0930 and 1000hrs. Light-artillery batteries were pushed forward to cover the next phase of advance by 1100hrs. As the 1st Division approached the third objective line, IV Corps issued orders to secure the first-day objective, enemy positions between La Marce and Nonsard, as soon as possible. At 1100hrs, with renewed artillery support, the support battalions passed through the assault battalions and led the advance through the enemy wire, which proved far less of a barrier than feared. The infantry forded the Rupt de Madine, but the supporting tanks found the steep bank problematic and several became disabled. By 1230hrs, led by a platoon of tanks from Major Brett’s 326th Tank Battalion, the 1st Division had captured Nonsard, securing the first-day objective. Brett’s tanks rooted out the sporadic German defenders, destroying a machine gun hidden in a church steeple with their 37mm guns. The reserve battalions and machine-gun companies were moved forward to defend against the expected German counterattack. The provisional squadron of the 2nd Cavalry was also moved forward to exploit any breakthrough.

Captain Eddie Rickenbacker described the scene from the air as he flew over the southern face of the salient during the morning of September 12:

Closely pressing came our eager doughboys fighting along like Indians. They scurried from cover to cover, always crouching low as they ran. Throwing themselves flat onto the ground, they would get their rifles into action and spray the Boches with more bullets until they withdrew from sight. Then another running advance and another furious pumping of lead from the Yanks.

To the east of the 1st Division the 42nd Division also advanced, with all four regiments in line with one battalion designated as assault, one as support, and one as reserve. The 83rd Brigade, composed of the 166th Ohio and 165th New York regiments, formed on the left while the 84th Brigade with the 167th Alabama and 168th Iowa regiments deployed on the right. Engineering squads were assigned to each assault battalion to open gaps in the wire and facilitate the crossing of streams and trenches by tanks and artillery. Initial orders directed the division to secure the second objective line, running from northeast of Nonsard, south of Lamarche, and north of Thiaucourt, by the end of the first day.

The 42nd Division pushed off at 0500hrs and found the German wire rusted and easily overcome. The division’s 83rd Brigade and the 167th Alabama advanced without serious resistance. The 3/168th Iowa ran into the German 6th Grenadier Regiment of the 10th Division in the Bois de Sonnard. The Iowans were slowed by bands of new barbed wire and strong resistance from German machine guns. The assault battalion took cover and began to suffer from sporadic Minenwerfers, which blew huge craters among the infantry. The American tanks lumbered through the mud and shellholes toward the wood as the Iowa officers cajoled their men to advance quickly and use their bayonets. Captain Dean Gilfillan, commander of Company A, 327th Tank Battalion, led a platoon of tanks toward the wood and knocked out several machine-gun positions. Company M on the far left of the Iowa line lost all its officers while Company K was left with just one lieutenant. On the right, led by the twice-wounded battalion commander, Major Guy Brewer, the 3/168th broke into the woods and rushed at the Germans in the trenches with bayonets. It was over in a matter of minutes and by 0630hrs word was received that the woods were secure. The action cost the 3/168th over 200 casualties while taking over 300 German prisoners from the 6th Grenadier and 47th regiments.

The rest of the 42nd Division continued forward, meeting little resistance. The 3/166th Ohio pushed aside weak resistance at St Baussant, capturing the village with few casualties. Company M was assigned the task of rounding up the Germans hiding throughout the village while the rest of the battalion moved across the Rupt de Mad and toward Maizerais. At the same time the 1/165th New York moved toward the village on the right. The 1/165th advance was stalled by German defense of the stone bridge over the Rupt de Mad. Ordering mortar and 37mm fire to tie down the defenders, Colonel Donovan forded the stream with a platoon and captured 40 men, one mortar, and four machine guns.

American tanks suffered from mechanical breakdowns and the difficulties of moving through water-soaked terrain. This tank is being removed from a ditch.

The FT-17 Renault tank spearheaded the American advance of the 1st and 42nd divisions.

Captain Eddie Rickenbacker was a popular automotive racecar driver before joining the Army and eventually entering the Army Air Service. Already an ace, Rickenbacker would shoot down an enemy aircraft on both September 14 and 15.

By 1100hrs the first objective line had been reached. At noon, orders came to continue the advance and the 42nd moved quickly toward Essey. Elements of both the 1/165th and 3/166th, supported by a section of French Schneider tanks and tanks from the 327th Tank Battalion, advanced against Essey. Patton, who had spent the morning trying to keep in touch with Compton’s 327th Tank Battalion, joined the infantry south of the village. Patton conferred with Brigadier-General Douglas MacArthur on a small hill, watching the German retreat.

By this time several groups of American tanks were approaching the town and Patton directed a platoon into Essey, followed by MacArthur and Donovan’s 1/165th infantry. After securing the village, Donovan sheltered his men in walled gardens to protect them from random artillery rounds. French civilians and groups of Germans bailed out of their dugouts and surrendered to the infantry and supporting tanks. The supporting battalion, 2/165th, began organizing the prisoners and collecting captured material, including several barrels of beer, which Colonel Anderson, commander of the 2/165th, ordered destroyed.

MacArthur and Patton continued their advance toward Pannes, passing the remains of German artillery, men, and horses that had been caught in the American artillery barrage. Patton and several of his tanks pushed through Pannes, heading for Beney. German machine-gun fire riddled the turret of the tank Patton was riding, forcing him to take cover in a nearby shellhole. After unsuccessfully requesting support from the nearby infantry, Patton caught up with the single tank and guided it back to Pannes.

By 1230hrs the remainder of the tank platoon arrived and a coordinated assault was organized. The 3/166th supported Patton’s tanks in a direct approach to Beney while the 3/167th outflanked the village on the right. A platoon of 3/167th accompanied by tanks entered Beney, cleared the town, and continued to the Bois de Beney. The infantry and tanks captured 16 machine guns and a battery of four 77mm guns in Beney. Donovan’s infantry, accompanied by the tanks, moved through Pannes, headed for the second objective line, the Bois de Thiaucourt, to the west of Beney. Supported by Patton’s tanks, the 1/165th drove the Germans from the woods and secured the Bois de Thiaucourt.

In Pannes the American infantry discovered a German quartermaster’s storehouse, yielding a treasure trove of souvenirs including pistols, spurs, hats, helmets, underwear, and musical instruments. The Germans waited for their captors in their dugouts. One German was found with a bottle of schnapps and a glass; he immediately offered his captor a drink, saying, “I don’t drink it myself, but I thought it would be a good thing to offer to an American who would find me.”

The 89th Division, on the far right of IV Corps, was expected to attack in the direction of Euvezin, keeping pace with the 42nd Division on its left and 2nd Division on the right. The 89th Division’s placement opposite the Bois de Mort Mare reflected the overall strategy of the First Army: to direct the veteran divisions across open ground where they could move quickly to exploit German weakness while the less experienced divisions would engage the Germans deployed in the woods. The Bois de Mort Mare, an extension of the Bois de Sonnard that caused the 42nd Division difficulties, masked the entire front of the 89th Division with the exception of two narrow open strips north of Flirey. Division staff decided to have the 177th Brigade flank the wood on the east. The 354th Regiment was detached from the 177th Brigade to form the brigade and divisional reserve.

The 178th Brigade, occupying twice the frontage of the 177th, was deployed on the left and tasked with forcing its way through the wood. At 0500hrs the 3/355th and 3/356th regiments, deployed side by side, moved directly toward the Bois de Mort Mare through a storm of artillery and machine-gun fire. Officers leading from the front were struck down as both regiments approached the southern edge of the wood. Rushing forward, the Americans overran the first German trench, a second trench deep in the wood, and finally a trench along the wood’s northern edge. American casualties were severe, particularly among officers. The 356th Regiment captured over 100 Germans, mostly from the 257th Regiment of the 77th Reserve Division.

Men of the 42nd Division and American tanks moving through Essey. It was near Essey that Brig. Gen. MacArthur and Col. Patton met briefly and chatted while enduring a German artillery barrage.

Men of Iron by Don Troianni. Although German resistance was sporadic, fierce battles took place in the Bois de Mort Mare between American infantry and German defenders.

On the right, the 2/353rd Regiment, 177th Brigade, skirted the Bois de Mort Mare, taking fire from Germans in the wood and from the Ansoncourt Farm at the southern edge of the Bois d’Euvezin. By 0515hrs every officer in Company E was killed or wounded, but despite taking over 200 casualties word was sent back that Ansoncourt Farm had been captured and that the Americans were entering the wood. Infantry from both the 355th and 353rd regiments slowly made their way through the dense underbrush, avoiding the trails and paths, which they suspected were registered by the German machine guns. Outflanking the enemy guns, the Americans methodically cleared the wood, showing little mercy to those gunners who fired until surrounded, but capturing hundreds of the enemy before stopping at the northern edge of the forest. The 2/353rd continued into the Bois du Beau-Vallon, taking another 200 prisoners and 15 machine guns. At the northern edge of Vallon the 3/353rd advanced through the battle-weary 2nd Battalion and took up the advance.

Following behind the assault battalion, the 1/353rd cleared German resistance in the Bois de Mort Mare, capturing Germans who were surprised that they had been surrounded. Private Joseph Szczepanik, advancing alone, gathered 150 German prisoners from their dugouts before being wounded. Both woods were secured by 0800hrs.

Advancing north from the wood, both brigades re-established contact and moved to the heights north of Euvezin, where they halted to reorganize. At 1100hrs the 3/353rd reached the first objective line, south of Bouillonville, and waited while the 1/355, moving up to replace the 3/355th as assault battalion, moved up on their left. The 3/356th failed to keep pace, delayed by thick woods and prolonged German resistance, and would not reach the front until 1500hrs.

COMBINED-ARMS ATTACK ON BENEY, SEPTEMBER 12, 1918 (pp. 50–51)

Lieutenant-Colonel Patton accompanied elements of the 326th and 327th tank battalions in their advance on September 12. In the late morning Patton directed tank operations against Essey and Pannes in conjunction with infantry elements of the 42nd Division. After securing Pannes, Patton rode on the rear deck of an American tank as it moved toward Beney. German machine-gun fire drove him off to find cover with infantry of the 167th Regiment. Failing to convince the infantry commander to accompany his lone tank in an attack on Beney, Patton was forced to order the tank to return to his position. At 1230hrs four additional tanks arrived and Patton convinced the infantry commander to accompany them in a coordinated attack. The attack stalled short of the town when the infantry moved into the Bois de Thiaucourt. Patton ordered the tanks to follow. At 1400hrs two additonal tanks joined Patton’s force and with another platoon from the 167th Regiment the American tanks and infantry captured Beney in the late afternoon.

Patton (1) is shown standing next to the FT-17 Renault tank (2), gesturing toward Beney. Men from an infantry platoon from the 167th Infantry Regiment mill around the tank platoon, wearing raincoats to protect them from the rain (3). The soldier in the foreground is armed with a Winchester shotgun (4). The Winchester Model 97, with pump action, fired a 12-gauge shell from a six-round magazine. The effectiveness of the shotgun in clearing German trenches and defensive positions resulted in the German government lodging a formal protest with the American government in September 1918, claiming that the weapon violated the terms of the Hague Convention, a forerunner to the Geneva Convention. The protest was rejected.

The repair of roads was critical to assuring that supplies and supporting artillery could move forward to support the American advance.

The 89th Division commander, Maj. Gen. Wright, who had moved his headquarters to Flirey at 1000hrs, set about moving the divisional artillery beyond the Bois de Mort Mare. Engineers were ordered to improve the road north from Flirey and a regiment of artillery was deployed north of the Bois de Mort Mare by mid-afternoon. At the same time, Wright received revised orders from I Corps directing his division to continue its advance to the army objective. The revised objective line extended from the center of the Bois de Dampvitoux, 2½ miles north of Beney, to Xammes. To occupy this line the 89th Division would have to wheel left to the northeast, using Xammes as the pivot.

While waiting for the 178th Brigade to come up, the 3/353rd sent out patrols, which immediately drew scattered machine-gun and artillery fire. Brushing aside the German defenders, the 3/356th entered the town, finding hundreds of German 10th Division support personnel waiting patiently to surrender to someone. Sergeant Harry Adams followed a German soldier to a dugout built into a hillside. After firing his last two bullets from his pistol into the door he demanded that they surrender. Waving his now-empty pistol menacingly, Adams herded a lieutenant-colonel and over 300 prisoners to the rear.

I Corps

Liggett’s I Corps objective was high ground north of Thiaucourt, strategically located on the railroad from Onville. Liggett designated the veteran 2nd Division as the point of the spear.

The 2nd Division was required to move through three woods: Bois la Haie l’Evêque, the Bois du Four, and the Bois de Heiche. Thiaucourt, located along the Rupt de Mad, was the largest town in the salient after St Mihiel. The division deployed on a 1½-mile-wide frontage, with the 3rd Brigade (9th and 23rd regiments) taking the forward position, followed by the 4th Brigade (5th and 6th Marine regiments). Opposing them was the German 419th Regiment of the 77th Reserve Division. The 419th Regiment deployed its 2nd and 3rd battalions in the forward edge of the Bois la Haie l’Evêque and the Bois du Four. The German artillery’s protective line was located at the back edge of the woods, supported by a Landsturm battalion and a pioneer company. The 1/419th was in the divisional reserve, south of Thiaucourt.

A German battery of 120mm and 210mm artillery captured at Thiaucourt’s railroad station.

German narrow-gauge train captured by the 2nd Division on September 12. The Germans had developed an extensive system of regular- and narrow-gauge railroads in the St Mihiel salient, used primarily for the movement of matériel and supplies.

The 2nd Division had received a steady supply of replacements, increasing divisional strength to 28,600, about 1,400 over its nominal strength. The experience of the 3/6th Marines was typical. On the day before the attack the battalion received 250 replacements, which were distributed throughout the companies. The men were given two extra bandoliers of rifle ammunition, extra Chauchat ammunition, and rifle grenades. Some 20 percent of each company was sent into reserve. The 3/6th was assigned a Stokes mortar platoon, a 15-man 37mm gun section, 40 pioneers for wire-cutting, and eight engineers to ensure coordination with the tanks.

Army orders established the 2nd Division’s first-objective line as the Bois de Heiche. The 3/9th and 2/23rd were positioned to lead the 3rd Brigade advance, supported by a machine-gun barrage to be delivered by the 4th and 6th Machine-gun battalions. A gas-and-flame company and three companies of tanks were also attached to the 3rd Brigade.

Responding to orders for the Gorze Group to deepen its outpost zone while withdrawing the main line of resistance to the artillery’s protective line, Major Nauman, commander of the 419th Regiment, issued new orders at 1830hrs on September 11. The outposts were to remain in place with machine guns but the bulk of the front-line battalions were to withdraw. These movements were well under way when the American barrage began at 0100hrs. The 2nd and 3rd battalions disintegrated under the barrage. The regimental commander and staff disappeared some time during the evening and the 1st Battalion, split into companies, made a feeble stand before collapsing under the weight of the American attack. Only 300 men of the 419th Regiment could be located on September 13.

At 0500hrs each forward company advanced in four waves, each separated by 50yds. The first two waves deployed into a thin skirmish line, with 5–10yds between each man, and the last two lines were in small columns, accompanied by the machine guns, mortars, and 37mm guns. The companies were separated by 200yd intervals and the battalions by 500yd gaps. German resistance was negligible and the 3rd Brigade moved quickly to occupy the German artillery protective line along the northern edge of Bois du Four by 0700hrs. Without pausing, the American line continued into Bois de Heiche, occupying the northern edge by 0900hrs. German defenders in the Bois la Haie l’Evêque established a loose defensive line that held up the Americans momentarily before retreating in the face of concentrated rifle fire.

American artillery pummeled the German lines while the 3rd Brigade reorganized. The 9th Regiment, which had widened its frontage during the initial advance, moved the 2/9th and 1/9th to forward positions. The 2/23rd remained the assault battalion on the left. At 1100hrs the advance continued and the German 257th Reserve Infantry Regiment attempted to make a stand on a ridge south of Thiaucourt. The German line was swept away as the 23rd Regiment passed through Thiaucourt at about noon and the 3rd Brigade reached the first-day objective by 1300hrs. The 2nd Division gathered over 3,000 prisoners, 92 guns loaded on a train, a hospital train, an ammunition train, and empty freight cars.

To the east of the 2nd Division, the 5th Division was given the objective of capturing the Bois de la Rappe. The plan then called for support battalions to advance another 2 miles, through the Bois Gérard and the heights northeast of Viéville. The 332nd Regiment, rated third class by American intelligence, faced the 5th Division. The German first line, composed of a single trench protected by bands of barbed wire, ran through open country west of the Bois de la Rappe. Beyond the first line the Bois des Saulx, Grandes Portions, and Bois St Claude formed the second combat position. The second position included two trenchlines with concrete strongpoints and reinforced dugouts.

The advance began at 0530hrs with the 10th Brigade (6th and 11th regiments) moving quickly through the wire, which they found rusted and in poor condition. A steady stream of German prisoners, including the commander of the 332nd Regiment, made their way to the rear in the wake of the American advance. Opposition stiffened briefly at the Bois des Saulx and St Claude, but by 0700hrs the 11th Infantry Regiment swept into Viéville just behind the creeping barrage. At 0930hrs the 10th Brigade drove through the Bois Gérard and occupied its first objective line. As the Americans mopped up the woods they found a large German hospital and a well-developed recreation camp, complete with a rustic beer garden and huts wired with electric lights. Working directly behind the 5th Division infantry, the 7th Engineers began clearing and rebuilding the road network to allow supplies to flow to the front. Rolling kitchens and medical facilities were also moved forward and ambulance dressing stations were established at various points along the front line. The 2/60th and 2/61st from the 9th Brigade were ordered forward to support the 10th Brigade, and the advance continued toward the first-day objective. In accordance with the corps plans, the line of advance shifted to the northeast, and by 1330hrs the army objective had been secured and the troops began to dig in.

Infantry of the 5th Division advancing through barbed wire. American planners were concerned about the impact of large areas of German barbed wire on the initial American advance. Despite its appearance, much of the German wire turned out to be rusted and poorly maintained.

Advancing American troops found extensive German rest camps throughout the St Mihiel salient.

Deployed near the easternmost end of the American line along the southern face of the salient, the 90th Division had the shortest distance to move. The division was ordered to attack with the 180th Brigade on the right, making a limited advance, while the 179th Brigade on the left was expected to keep pace with the advance of the 5th Division. In the 179th Brigade sector the 357th Regiment, placed on the left, assigned the 1/357th as the assault battalion, the 2/357th as support, and placed the 3/357th in brigade reserve. The regiment was directed to move through the Bois de la Rappe and Bois St Claude and support the 5th Division’s capture of Viéville. The 358th Regiment, on the right, was assigned enough frontage to deploy the 3/358th and 2/358th as assault battalions with the 1/358th in support. The 358th’s objective was the Bois de Frière.

In the 180th Brigade sector the 3/359th Regiment was expected to maintain contact with the 3/358th and capture the Quart de Reserve, a 320yd2 square of shattered trees. The 2/359th would support the attack on the Quart de Reserve while the 1/360th and 3/160th, on the far right of the divisional sector, were to remain in place facing the Bois-le-Prêtre.

As the 0500hrs jump-off time approached, the assault battalions noticed that the supporting barrage along their front was relatively thin. Prior to the attack, patrols and working parties had attempted to cut lanes through the barbed wire but had been stymied by a lack of wire-cutters. Frustrated by their inability to secure the cutters through the Army’s supply system, divisional staff created a minor scandal when they attempted to purchase the wire-cutters in open markets in Toul and Nancy. By the time of the assault 400 heavy-duty wire-cutters had been procured for each brigade.

Arrayed opposite the 90th Division was the German 255th Division, rated as fourth class by American intelligence, but still able to put up stiff resistance to the American attack. On the left the 1/357th surged forward, crossing a mile of open country, through the wire and German machine-gun fire, and penetrating the Bois de la Rappe. Between the Bois de la Rappe and the Forêt des Venchères, across the road between Viéville and Vilcey-sur-Trey, was a ravine, later named Gas Alley. Machine-gun emplacements covered the steep slope leading from the road up to the edge of the Forêt des Venchères. The 1/357th struggled up the slope, swept by machine-gun fire. Officer casualties were severe but the battalion’s assault brought them into the German position. Moving up in support, the 2/357th also suffered from enemy fire and found itself engaged in mopping up strongpoints bypassed by the 1/357th. The 2/357th also supported the advance of the 3/358th on their right, which was struggling to capture the Bois de Frière.

Even before the attack began, the 3/358th suffered from German artillery fire as it moved toward its jump-off positions. Major Terry Allen was wounded by shrapnel and taken to an aid station. After regaining consciousness Allen refused treatment and returned to the front, assembling ragtag groups of stragglers along the way. Allen and his men then surprised several German strongpoints bypassed by the 3/358th in its initial assault, the men fighting in close quarters with their fists after exhausting all their ammunition. Allen was wounded again in the hand-to-hand combat, losing several teeth in the process, and was later evacuated.

The 3/358th suffered from difficult terrain and German defenses. With only five out of the 12 officers in the battalion still in action, the advance bogged down. Elements of the 1/358th, coming up in support, became intermingled with the 3/358th as they struggled up the wooded valley. Captain George Danenhour, commanding Company B, and Captain Sim Souther, commanding Company M, decided to capture Vilcey-sur-Trey before nightfall, but their attack faltered several hundred yards short of the town.

Movement of supplies to the front along overcrowded roads created logistical problems throughout the St Mihiel offensive.

FIGHTING IN THE BOIS DE FRIÈRE, SEPTEMBER 12, 1918 (pp. 62–63)

The 3/358th Infantry, 90th Division, was designated the assault unit for the American attack on the morning of September 12. As they were moving forward toward their jump-off positions before dawn, the unit was caught by German counterbattery fire. Major Allen, battalion commander, was wounded and evacuated while unconscious to an aid station in the rear. Regaining his senses, Allen removed his medical tag and sought to rejoin his unit, which had already advanced through the Bois de Frière. Allen gathered a group of men separated from their units and led them forward. They discovered a group of Germans bypassed by the first wave of American troops emerging from their dugout. Allen led his men in desperate hand-to-hand combat with the Germans. After emptying his pistol and despite his wounds, Allen fought with his fists, losing several teeth and suffering another serious wound.

Allen and his men are shown engaging the Germans in the trench. On the morning of September 12, American troops wore raincoats to protect against the rain. Allen (1) is using his .45-caliber pistol (2), which was standard issue for American officers. American tactical doctrine required the assault battalions to advance as quickly as possible toward their first objective line. Follow-on battalions were given the task of mopping up German strongpoints bypassed by the leading troops. The American early morning artillery barrage drove many German units into the protection of their dugouts (3) and many were passed over by the first wave of American troops. During the St Mihiel offensive several American support units engaged in desperate battles to clean out small groups of Germans scattered throughout the woods.

Allen would rise to command the American 1st Infantry Division in North Africa and Sicily in World War II. Criticized for lax discipline, Allen was relieved of his command by General Dwight Eisnhower. Allen was then assigned to command the 104th Infantry Division and he led them through the Battle of the Bulge and Germany’s surrender in May 1945.

While the 3/358th was delayed in its advance, to their right the 2/358th was also hampered by German wire and machine guns. During the initial advance the battalion commander and two company commanders were wounded, leaving Captain John Simpson, of Company G, to assume command of the battalion. By 0715hrs several platoons of Company F had secured the objective line and gathered over 150 prisoners. German snipers covering the forest paths were neutralized by American “squirrel hunters” from Oklahoma and Texas; Corporal Wilbur Light won the Distinguished Service Cross for shooting six snipers out of their perches. It wasn’t until 1400hrs that the remainder of the battalion came forward. The 3/358th was then ordered to secure La Poêle, a German strongpoint, and settle in for the night.

In the 180th Brigade sector 3/359th was required to slide westwards to its jump-off position. Orders were received late and not all officers were immediately informed of the move, resulting in delays in distributing ammunition and food. Combined with the darkness and rain, this resulted in several platoons being late in settling into their initial positions. The Germans defended the Quart de Reserve tenaciously. With the support of the 2/359th and despite heavy casualties, particularly among officers, companies K, L, and M occupied the Rhenane trench by 1300hrs, where they consolidated their positions. The 2/359th spent the remainder of the day securing its position and eliminating pockets of German resistance.

The role of the 82nd Division was to act as the hinge on which the I and IV Corps door would swing. While it was not expected to engage in a wholesale advance, its position was complicated. The division straddled the Moselle River, facing the German 255th Division on the west back of the Moselle together with the 84th Landwehr Brigade and 31st Landwehr Brigade. The division was expected to exert pressure on the enemy through aggressive patrols. On September 12 strong patrols were sent out to probe the German lines. A force from the 327th Regiment engaged the Germans at Bel Air Farm on the east bank and retired under strong pressure from the enemy. On the west bank of the Moselle three platoons from Company F, 328th Regiment, approached the town of Norroy, penetrating the German defenses before withdrawing. Patrols from the 325th Regiment reached Eply while probes from the 326th Regiment attacked German positions west of the Bois de la Voivrotte.

V Corps

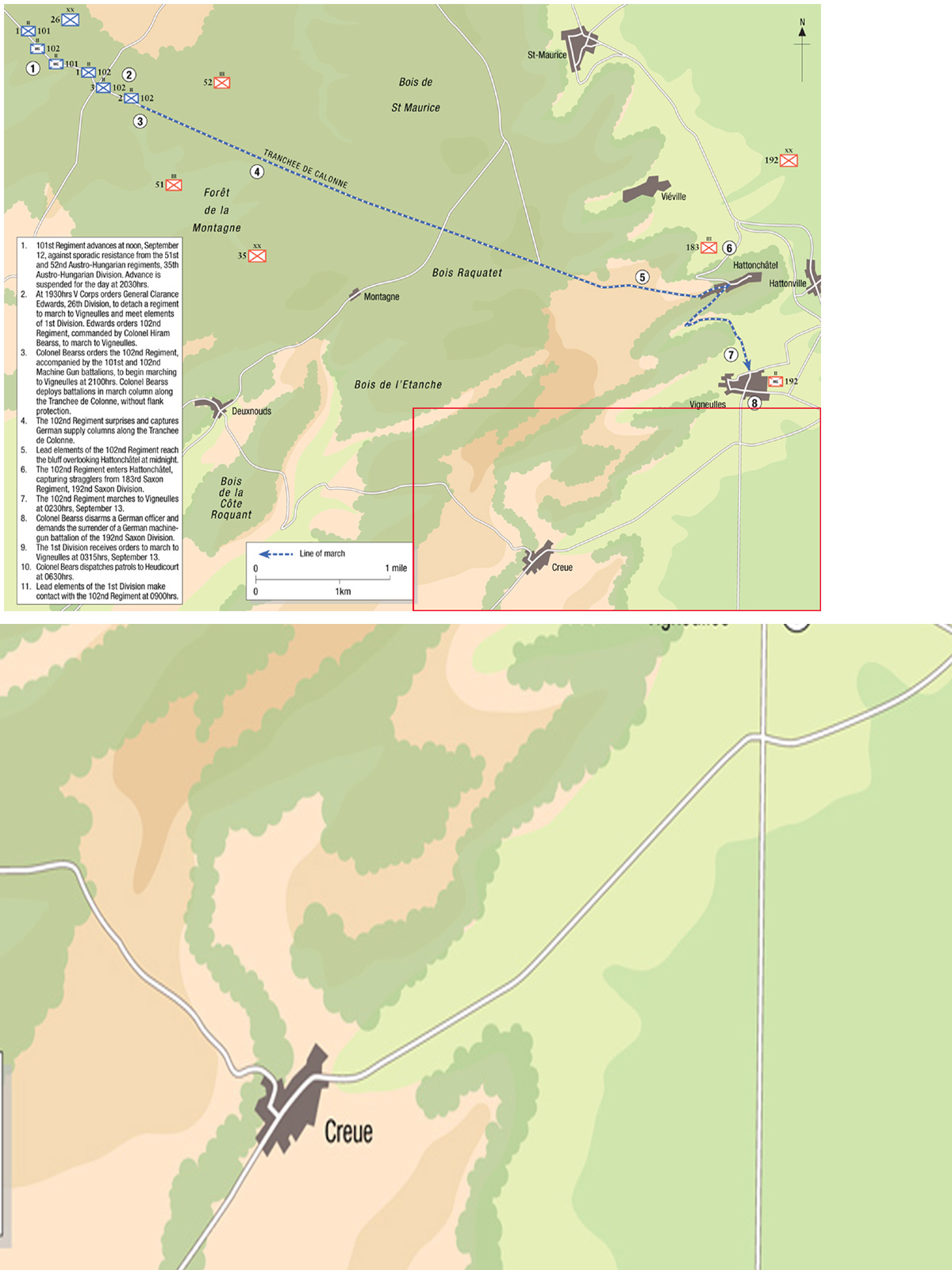

On the western face of the salient Maj. Gen. Cameron’s V Corps, led by the 26th (Yankee) Division, waited while I and IV Corps attacked the southern face. In order to further confuse the Germans, the corps was not scheduled to attack until 0800hrs. The 26th Division faced hundreds of yards of barbed wire followed by a dense system of trenches. The 51st Brigade held the right of the divisional sector. The 101st Regiment was assigned to lead the assault, followed by the 102nd Regiment in support. On the left the 52nd Brigade was formed by the 103rd Regiment and 104th Regiment abreast. The first-day objective was a ridge southeast of the Dompierre–Longeau Ferme road. Facing the 26th Division was the understrength and unmotivated 13th Landwehr Division.

Following the preliminary barrage, the men of the 26th Division moved with high anticipation into the attack. To their surprise resistance was minimal and the division was able to advance over a half-mile without serious opposition. On the far left of the 52nd Brigade sector the 104th Regiment advanced quickly, overcoming isolated pockets of resistance. To its right the 103rd Regiment encountered German machine guns in the Bois St Rémy. Flanking the German strongpoints, the 103rd Regiment shot down the gunners and continued its advance, capturing an entire enemy battalion.

On the right the 101st Regiment, deployed with two battalions in line, found itself struggling through a belt of wire measuring 90ft deep. Advancing cautiously on either side of the Grande Tranchée de Colonne, through a half-mile of shattered woods, the regiment approached the Vaux–St Rémy road and slammed into a strong line of well-constructed trenches augmented by concrete strongpoints. German artillery fire, which up to this point had been ineffective, began to fall among the American infantry. Recoiling briefly, the American infantry began to work its way around the strongpoints. Around noon the support battalions of the 102nd Regiment and 101st Machine-gun Battalion were ordered forward. After a quick reconnaissance by the 26th Division Chief of Staff, the 1/102nd was ordered to advance through the 101st and continue the attack. Colonel Hiram Bearss, commander of the 102nd Regiment, directed the 1/102nd to move forward at 1600hrs. Several men infiltrated the German line, surprising and capturing enemy machine-gun positions from the rear and unhinging the German defensive position. The 1/102nd quickly cleared the German defenses.

On the left, the 104th Regiment reported they had lost contact with the French 15th Colonial Division. The French had captured St Rémy at 2330hrs but their attack bogged down as German resistance stiffened around Amaranthe Hill. Although the 104th Regiment reported sporadic German rifle fire there was no serious danger to the open flank and the American advance continued. The V Corps staff noted the failure of the French to keep up with the 26th Division and reassigned responsibility for a portion of the front from the 15th Colonial Division to the 26th Division. The 103rd and 104th regiments continued forward into the Bois-le-Chanot. A battery of 155mm guns was captured by the 104th and both regiments extended skirmish lines south toward Dommartin. Furious German machine-gun fire greeted the Americans as they worked their way up the slope toward the town. The Americans retreated back to the woods and began digging in for the night.

A German prisoner receiving medical treatment from medics of the 26th Division. Heavy rain during the night of September 11 and into the early hours of September 12 resulted in most American infantry wearing raincoats over their uniforms.

Narrow-gauge railroad and German defenses captured near St Rémy. The Americans quickly made use of captured German railroad equipment and tracks to supplement the movement of supplies and reinforcements to frontline units.

German prisoners taken by the 26th Division in Dommartin. The poor quality and low morale of most German units in the St Mihiel salient resulted in frequent wholesale surrender.

As the 26th Division was consolidating its positions Maj. Gen. Edwards was conferring with French 2nd Dismounted Cavalry Division commander, General Hennocque, on what steps to take next. Hennocque, whose forces had kept pace with the Americans on the right, proposed a shift to the left and an advance north toward St Maurice. Edwards agreed and directed his staff to begin preparations for the movement. On the heels of this decision V Corps commander Maj. Gen. Cameron, acting on a directive from Pershing, ordered Edwards to drive southeast to Vigneulles where they would link up with troops from the 1st Division and close the salient. Playing on longstanding tension between the National Guard officers and men of the 26th Division and the regular army leadership, Cameron told Edwards, “This is your chance, old man. Go do it … try and beat the 1st Division in the race and clean up.”

War in the air

While the doughboys were shivering in mud-choked trenches enduring a night of driving rain, Colonel Billy Mitchell’s airmen waited in their hangars and briefing rooms for permission to fly. Major Joseph McNarney, commander of the IV Corps Observation Group, assembled his squadron commanders. He outlined their mission for the next day and reminded them that aviation would be “a very essential part of the attack and whatever the weather the missions were to be performed as long as it was physically possible for planes to take off.”

Mitchell had positioned his pursuit squadrons around the flanks of the salient along with his reconnaissance groups. The pursuit squadrons were expected to protect the observation planes and to maintain control of the air. Mitchell’s plan was to coordinate observation, pursuit, and bombing missions to both support the advance of the American infantry and disrupt the German retreat. Low clouds, driving rain, and high winds conspired to unravel Mitchell’s overall plan of attack. Most squadrons delayed their missions in the hope that the weather would improve. With the poor flying conditions the planes would have to fly low and it was still doubtful whether they would be able to see anything of value, considering the poor weather. Similarly, American balloons proved useless in the rain and wind. Those balloons that did rise reported poor visibility and their missions were canceled.

The French Nieuport 28, flown by American pursuit squadrons. This late variant of Nieuport’s biplanes was used mainly by American pilots, notably Eddie Rickenbacker, the French having switched over to Spads.

In the early morning gloom several aircraft did get aloft and witnessed the American advance and German retreat. Observer planes reported that the Vigneulles–St Benoît road was full of men, artillery, and wagons, all in retreat. Throughout the morning small flights of observers, pursuers, and bombers managed to lift off. Once airborne, the planes experienced further frustrations in communication with ground forces. The 8th Aero Squadron found it impossible to communicate effectively with 1st Division or brigade staff. A lack of radios among ground units limited messages to handwritten notes placed in cylinders that were dropped at headquarters.

Overall, more than 50 sorties were flown by I Corps Observation Group on the first day of the offensive. On the western face of the salient V Corps Observation Group also flew some successful missions, with pilots from the 99th Aero Squadron reporting that the infantry of the 26th Division was advancing rapidly and that several villages were on fire.

The critical responsibility for penetrating the German rear areas and monitoring enemy troop movements was assigned to the First Army Observation Group. The 91st Aero Squadron, a veteran unit, which had been flying in the St Mihiel region since the spring of 1918, shouldered the bulk of the work. Although frustrated by the same weather conditions that plagued the other groups, one observer team penetrated over 50 miles into the rear of the German position and reported clear evidence of a general retreat.

German reaction

Confusion was the watchword in Army Detachment C’s headquarters as information about the American attacks dribbled in. At 0700hrs it was clear that a general offensive was under way. Encouraging news filtered in at 0800hrs that a feeble attack by the French in the sector held by the 5th Landwehr Division had been repulsed. At 0930hrs the first indications that the 77th Reserve Division was in trouble reached Fuchs, with reports that retreating units had been observed in the 77th Reserve sector. In response he assigned men from the 31st and 123rd divisions to move up in support of the 77th Reserve Division and the 10th Division. The 255th Division reported that it was holding in the face of American attacks but that it had lost contact with the 77th Reserve Division on its right.

The reality on the ground was much more serious. The 77th Reserve Division had disintegrated and its neighbor the 10th Division was straining under the pressure. Unable to reach army headquarters, Gorze Group commander General Hartz ordered a counterattack by the 31st and 123rd divisions on his own initiative. The 31st Division was directed to attack through Thiaucourt and the 123rd near Viéville. Some time later communication with Conflans was restored and Hartz updated Fuchs on the deteriorating situation.

Once Fuchs and his staff overcame their initial shock at the news from the Gorze Group they began to develop a plan to restore the German front line. The 88th Division, provisionally assigned to the Combres Group, was reassigned to Hartz.

Any hope of salvaging the situation was further diminished at 1015hrs as preliminary reports suggested that the Americans had broken through the 77th Reserve Division, followed at 1050hrs with an official report from the Gorze Group that the 77th Reserve Division had been swept away and that the enemy was nearing Thiaucourt and Tautecourt Farm. Gorze also reported that there had been no signs of the expected counterattacks from the 31st and 123rd divisions. Fuchs concluded that the 10th Division’s left flank had been driven back and that the Americans, nearing Thiaucourt, were threatening not only to punch a hole in the Michel Stellung but endangering the retreat of the Mihiel Group at the front of the salient.

Most troubling was news from the 35th Austrian and 13th Landwehr divisions that a strong American attack had been launched from the western face of the salient. At 1100hrs Fuchs issued orders for the Mihiel Group to begin their withdrawal, the Loki movement, at once. At 1110hrs General Fritz von Below, commander of the Combres Group, reported that there was heavy fighting along the Combres Heights and that St Rémy had been captured. Recognizing the American strategy of pinching off the salient with the attack from the west, Fuchs told Below that the Heights must be held.

The town of St Benoît, in which the Mihiel Group’s headquarters was located, was the key to maintaining a corridor of retreat for the Group. The 65th Landwehr Regiment, 5th Landwehr Division, was directed to reinforce the defenses at St Benoît and shortly after noon the Mihiel Group began their retreat. The 5th Landwehr Division was ordered, in conjunction with the 192nd Saxon Division to its west, to maintain their forward battalions until 2000hrs and to remain in contact with American forces through aggressive patrols until the morning of September 13.

With the successful advance of the morning encouraging optimism in First Army command, I Corps ordered the 1st Division to resume its attack, with the goal of the first day-two objective line. At 1335hrs the provisional squadron of the 2nd Cavalry Regiment was dispatched to Nonsard. The cavalry was ordered to proceed along the Nonsard–Vigneulles road in the hope that they could take advantage of the disorganized German retreat. Starting out at 1720hrs three troops of cavalry quickly encountered determined German resistance where the roads passed into the Bois de Nonsard. Although they were able to capture several prisoners, the cavalry was unable to advance.

Throughout the afternoon the 75mm batteries were moved forward to support the next phase of advance. At 1745hrs the 1st Division moved north from Nonsard, securing the Decauville Road through the Bois de Vigneulles and Bois de Nonsard by 1945hrs. At 2200hrs elements of the 28th Regiment continued to move cautiously through the Bois de Vigneulles toward the main German line of retreat, the Vigneulles–St Benoît road. The 18th Regiment penetrated the Bois de la Belle Ozière to the west and patrols were dispatched toward Heudicourt.

The 1st Division moving in a long column through the rolling plains of the St Mihiel salient. The terrain of the salient was characterized by open fields punctuated by large woodlands.

Movement through the dense woods, infested with bands of Germans – some intent on surrendering, others putting up stiff resistance – was slow. Entire German companies were surrounded and captured, while the staff of a German battalion wandered into American lines searching for a predetermined rendezvous point.

Two battalions of the 42nd Division were temporarily reassigned to the 1st Division to reinforce its right flank. They were directed to be in Lamarche by 0400hrs. In addition, 6th Brigade, 3rd Division, was ordered to move forward as a 1st Division reserve.

During the afternoon of September 12 the 83rd Brigade, 42nd Division, established its headquarters in Essey. The 165th Regiment set up its headquarters in Pannes, extending patrols from the 1/165th into the southern portions of the Bois de Thiaucourt. The 2/165th was deployed in support and the 3/165th around Pannes. The 84th Brigade moved up to the east, the 168th settling in on the right of the 165th, along the southern edge of the Bois de Thiaucourt, while the 168th extended the line a half-mile northeast of Pannes. With that the 42nd Division settled down for the night.

More tanks from the 327th Tank Battalion gathered at Pannes through the course of the afternoon. The tanks were burning fuel at a much higher rate than predicted, primarily because of the mud and difficult terrain. By mid-afternoon the fuel situation was eased somewhat by a small amount moved forward on sleds pulled behind the supply tanks. An attempt to move gasoline supply trucks to Essey along the Flirey–Essey road was stopped by military police in Flirey, who refused to allow the trucks to move to Essey until the afternoon of September 13. Patton, satisfied that the 327th had achieved its objectives, started out in search of the 326th Tank Battalion in the 1st Division sector. In Nonsard he found Major Brett despondent about the small number of serviceable tanks remaining in the battalion but, more importantly, about being out of gasoline. After consoling Brett, Patton started for the rear to find more fuel.

The 89th Division Chief of Staff, Colonel C. E. Kilbourne, directed the 1/355th and 3/356th, already moving to join the 177th Brigade south of Bouillonville, to continue their advance toward the Bois de Dampvitoux. The 1/355th received the orders first and led the advance, the 3/356th on its left and the 3/353rd on its right. Moving through and beyond Bouillonville and finding no organized German opposition, the 1/355 reached its objective east of Bois de Dampvitoux at 1800hrs, while the 3/356th occupied the wood at 2000hrs and the 3/353rd moved into Xammes at midnight.

The 3rd Brigade, 2nd Division, having reached its first-day objective line at 1300hrs, paused to consolidate its positions. The 2/9th and 1/9th, deployed on the right of the brigade, had also reached the final army objective. On the left the 2/23rd pushed patrols out toward Jaulny and Xammes and by 1400hrs it had also reached the final army objective line. The 6th Marine Regiment, in support of the 23rd Regiment, maintained contact with the 89th Division on the left.

The 5th Division, having secured the army objective line at 1330hrs, sent strong patrols toward the Hindenburg Line. The division had lost contact with the 90th Division on its right, which had created a large gap. The 3/11th filled the gap, facing west. The 6th Regiment dispatched a patrol toward Rembercourt, scooping up prisoners. Later in the afternoon word was received that the 2nd Division forward elements were at Jaulny and the 5th Division realigned their left flank to conform to the 2nd Division movement. German resistance to 5th Division patrols became stronger later in the afternoon. In the early evening German reinforcements arrived between Rembercourt and La Souleuvre Ferme. The 174th Regiment, 31st Division, attacked the 6th Regiment in the Bois de Bonvaux while the 106th Regiment, 123rd Division, attacked the 11th Regiment. The German 123rd Division replaced the remnants of the 77th Reserve Division, which had lost over 1,100 men to the 5th Division.

By 1400hrs the 90th Division had fought its way to the first-day objective. In the process it had captured over 500 prisoners. While the infantry battalions began to consolidate their positions, patrols were pushed out over a mile toward the German Michel Stellung, resulting in more desultory fighting. A patrol from Company A, 357th Regiment, penetrated the German defensive lines, attacking and capturing a German battery but finding itself surrounded. The patrol fought their way back to the main line, losing only one prisoner. Machine-gun battalions were moved forward to buttress the line of defense. Although the advance on September 12 had succeeded in routing the German defenses, American commanders now feared a determined German counterattack during the night.

American tanks crossing a hastily repaired bridge. American engineering units were engaged throughout the offensive repairing bridges and roads in order to maintain American momentum and allow artillery and other support units to move forward.

Three American tanks disabled because of mechanical breakdowns. Between mechanical problems and higher-than-expected fuel consumption, American tanks saw limited action late in the day on September 12.

German prisoners were frequently used to carry American wounded from the battlefield to aid stations.

While American reconnaissance flights observed German supply wagons clogging the roads leading north and east out of the salient they also noted the movement of German infantry toward American positions, with IV Corps Observation Group reporting “between two and three thousand enemy troops on Chambley–Dampvitoux road entering Dampvitoux.” An hour later another pilot reported large numbers of enemy moving toward Thiaucourt from Waville.

Even as orders to begin the Loki movement directed an immediate retreat, Lieutenant-General Leuthold, the Mihiel Group commander, noted that the 5th Landwehr and 192nd Saxon divisions had repelled attacks from the II French Colonial Corps along the nose of the salient. The Loki movement limited a general retirement to the Schroeter zone and Leuthold issued orders in accordance with that plan. Unfortunately for Army Detachment C, the American advance had already penetrated the Schroeter zone early in the afternoon. At 1400hrs the 5th Landwehr Divison reported that Pannes and Nonsard had been captured, at which time the Mihiel Group staff determined that the “order issued by army headquarters at noon to hold the Schroeter zone had become obsolete.” Fuchs, who had also hoped to reconstitute his line in the Schroeter zone in order to save large stocks of supplies, bowed to the reality of the American penetration and directed Leuthold to retire to the Michel Stellung.

About that time the headquarters of the Mihiel Group was transferred from St Benoît to Lachaussee. The veteran 10th Division, pressed back by the American 42nd and 89th divisions, protected the Mihiel Group’s retreat. The German 88th Division was moving rapidly from Conflans to relieve the 5th Landwehr Division. German headquarters noted that American tanks and infantry were reported to be advancing from Nonsard toward Heudicourt. They concluded that the reserve battalion of the 65th Landwehr Regiment, which was marching to Heudicourt, would be sufficient to drive the Americans back toward Nonsard.

Despite losing large numbers of artillery pieces during the initial American attack, German reinforcements were deployed on September 13. Thiaucourt was subjected to repeated German artillery attacks.

Although surprised by the American attack, the Germans were able to destroy some strategic assests, such as this railroad bridge.

After a morning of rapid advance, with the American divisions threatening to cut off the Mihiel Group, I Corps and IV Corps were vulnerable to a German counterattack. American corps and divisional plans included provisions to guard against the prospect of a German reaction. As soon as the first line of resistance was broken American artillery was sent forward to support the next phase of advance or repel a German counterattack. Through the morning of September 12 the American rate of advance had exceeded the most optimistic assumptions, resulting in uncoordinated movements. Muddy ground and destroyed roads also conspired to frustrate the movement of artillery and other support units.

In a communiqué sent at 0530hrs Fuchs stressed that “there was no mistaking the danger to the Mihiel Group from a further advance of the enemy from Beney in the direction of St Benoît.” In order to blunt the American advance the 5th Landwehr Division launched a probe with the reserve battalions of the 25th and 36th Landwehr regiments from Heudicourt, with the intention of driving the American line between Pannes and Beney back toward Bouillonville. The advance of the two battalions against the flank of the American 1st Division made no impression, but was a reminder to the Americans that the Germans still had some fight left in them. Fuchs had more confidence in the anticipated counterattacks from the 31st and 123rd divisions. Poor communications, congested roads, and crumbling morale conspired to frustrate the German plan. Owing to the haphazard arrival of both divisions, neither attack materialized as intended. The 31st Division joined the remnants of the left wing of the 10th Division around Xammes and then extended its line westward to Jaulny. The 123rd Division deployed farther west, linking up with the 255th Division, and prepared to attack toward Viéville.

Rather than launch a coordinated counterattack, both divisions directed limited attacks late in the afternoon. The 1/9th, 2nd Division, occupied the ground south of Jaulny in the late afternoon and pushed out patrols into the town, capturing over 100 Germans before retiring. At 1700hrs the Germans subjected the 1/9th to machine-gun and artillery fire, causing it to pull back. As the Germans advanced out of Jaulny, American machine-gun fire, coupled with an artillery barrage, broke up the attack and by 1900hrs the front was quiet. Single regimental attacks from both the 123rd and 31st divisions struck forward elements of the 5th Division late in the afternoon without effect. Although Fuchs was unable to retake lost ground or seriously threaten the American advance, he had plugged the hole created by the disintegration of the 77th Reserve Division and continued to hold a line of retreat through Heudicourt, Vigneulles, St Benoît, and Dampvitoux. The 88th Division, which had originally been dispatched to replace the 5th Landwehr Division, was redirected to the Lahayville sector to reinforce the remnants of the 10th Division and protect the right flank of the Gorze Group.

The Combres Group resisted any deep penetrations of its zone throughout most of the day. The Austrian 35th Division retired in good order to its artillery line and the 13th Landwehr Division blunted the advance of the 15th Colonial Division, which in turn slowed the advance of the 26th Division. Austrian 35th Division commander Major-General Podhoransky was confident enough in the strength of this position that he did not authorize a further retirement until 1600hrs. At 1700hrs the Combres Group commander, General Below, ordered the full retreat of the 35th Division and 13th Landwehr Divison to the Michel Stellung.

Despite increased German aggressiveness late in the day, Pershing and his staff were convinced that they were in full retreat. In their assessment the Americans recognized that a window of opportunity had opened. In order to escape the closing jaws of the American attack the Germans needed to withdraw the bulk of their forces during the night. The deeper-than-anticipated penetrations of the American forces offered the possibility that those jaws could be snapped shut before the Germans could escape. Late in the afternoon Pershing abandoned the carefully prepared plans and timetables, which were now obsolete, and began to improvise. At 1700hrs Pershing called V Corps commander Maj.-Gen. Cameron and directed him to detach at least one regiment and march southeast toward Vigneulles. At the same time Pershing ordered Maj. Gen. Dickman to throw the 1st Division at Vigneulles from the south.

The 26th Division commander, Maj. Gen. Edwards, received Pershing’s order at 1930hrs and immediately set the advance in motion. Until Pershing called, Edwards had been reorienting his division to the northeast to assist the 15th Colonial Division in clearing the Heights of the Meuse. Edwards notified 51st Brigade commander Brigadier-General George Shelton just after 2000hrs of the change of plans and Shelton designated the 1/102nd to lead the advance. Following the lead battalion, the 102nd and 101st machine-gun battalions would march in support, followed in turn by the 2/102nd and 3/102nd. Shelton considered assigning a field-artillery regiment to the column, but the difficulty of moving guns in darkness over unknown terrain made him decide to send the infantry without artillery support.

Shelton’s plan, submitted to 1/102nd staff at 2100hrs, proposed marching down the Grande Tranchée roadway, built by Louis XVI to provide improved access to his chateau at Hattonchâtel, through the woods to Vigneulles. The 1/102nd commander, Col. Bearss, a cigar-smoking Marine officer, assembled his officers and announced that this was a race against the 1st Division. He also told them he planned to march directly down the road, without throwing out flanking parties to protect his column from ambush. Bearss believed the Germans to be on the run and unable to offer organized resistance. Darkness would work in his favor, sheltering his men as they worked their way down the Grande Tranchée to Vigneulles.

During the night march to Vigneulles, Col. Bearss and the 102nd Regiment surprised a column of German trucks parked along the road and took them prisoner.

Edwards directed his other brigade, led by Brigadier-General Eli Cole, to advance by roads east of Bearss’ brigade to St Maurice. The orders to Cole were late and by the time his battalion and company commanders were informed it was after 0400hrs. St Maurice was alight with burning ammunition and supplies when the first American patrols arrived around dawn to find the Germans gone.

The 1/102nd marched steadily along the Grande Tranchée, which had been used by the Germans as a main supply artery and kept in good shape. To ensure surprise Bearss ordered his men to empty their rifles and fix bayonets. Any opposition was to be met with cold steel. Throughout the march the Americans heard movement along either side of the road, which they suspected was the sound of groups of Germans trying to escape. Coming up on a line of trucks along the side of the road, Bearss’ men surprised the sleeping drivers and took them prisoner. Farther on, the Americans captured several staff officers and their car and then surprised another group, who were loading trucks with ammunition. A few shots scattered the German crews and the march continued. Just after midnight the column found Hattonchâtel in flames and to the east the Woëvre Plain alight with burning villages and supply dumps. Collecting German stragglers along the way, the 1/102nd continued toward Vigneulles. At 0230hrs on September 13 the Americans entered Vigneulles and quickly spread out.

As they moved to secure the town a German column appeared, marching from the opposite direction. Without hesitating, Bearss approached the head of the column and demanded their surrender. When the German commanding officer hesitated, Bearss laid him out with a right to the jaw and the men in the column threw up their hands. As they were corralling the prisoners a German wagon train, carrying a machine-gun battalion, appeared and suffered the same fate.

As the town was mopped up, reinforced patrols were sent south to Heudicourt and southwest to Creue, where additional prisoners were taken. Having won the race, Bearss was content to wait for the 1st Division to show up.

Unavoidable delays in transmitting orders from corps to division and then to brigade and regiment resulted in the 1st Division beginning its advance 45 minutes after Bearss had occupied Vigneulles. Starting out in pouring rain at 0315hrs, men from the 28th Regiment captured several German prisoners before running into two doughboys coming from the direction of Vigneulles. After some initial confusion, word went out to First Army command that Vigneulles was in American hands.

Throughout the night a jittery American staff at both army and corps levels fretted over the expected German counterattack. During the night several Germans from the 31st Division were captured and confirmed the deployment in the Michel Stellung.

Rumors of a German counterattack consumed the I Corps staff around midnight. A wireless message from the 2nd Division requesting immediate artillery support for the 26th Regiment, which was said to be under attack, resulted in the release of a brigade of the 78th Division to support the 2nd Division and a furious artillery barrage along the 26th Regiment’s front. General Lejeune, 2nd Division commander, was puzzled by the message. As far as he knew the division was not under attack and passed that information back to corps staff. Because of broken communications wires and German jamming of the wireless radios, Lejeune’s message was never received. The 2nd Division Chief of Staff responded later in the morning, “What goddamned fool sent the report about counterattack and falling back? If I can find the son-of-a-bitch I’m going to shoot him… The 2nd Division is to hold the Army objective as laid down and defined. That ends it.”