In the last days of November 1948, I made ready to cover what was to become one of the largest battles in history. It would affect the balance of power in world politics for generations to come. Strangely, perhaps because it was fought on distant hidden fronts, cloaked by Nationalist censorship and obscured by propaganda of the opposing sides, the Battle of the Huai-Hai would attract little notice abroad. During the climactic phase, I was the lone Western reporter with the Communist forces on a remote battlefield of the vast engagement and for a time their prisoner.

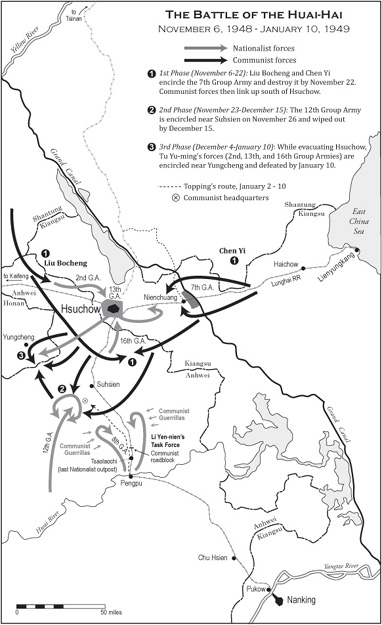

The Battle of the Huai-Hai, upon which the fate of Nanking and Shanghai would turn, pivoted on Hsuchow, a city of 300,000 in population, 175 miles north of Nanking, on the vast Huaipei Plain. The battle, involving more than a million troops, historically took its name from the Huai River, which flowed some 100 miles north of Nanking. Chinese historians would later compare the battle with Gettysburg, the decisive campaign of the American Civil War.

On October 11, Mao Zedong issued to his generals the field order which heralded the start of an offensive on the Nationalist-held Hsuchow salient. “You are to complete the campaign in two months, November and December. Rest and consolidate your forces in January . . . by autumn your main force will probably be fighting to cross the Yangtze to liberate Nanking and Shanghai.” To coordinate the vast operations Mao created a General Front Committee headed by Deng Xiaoping, later to become the paramount leader of China, then serving as trusted political commissar whose role was to ensure the loyalty of the troops. Mao’s field order contained detailed instructions to his commanders for the array of their divisions. To the battle Mao committed his Eastern China Field Army of some 420,000 troops commanded by Chen Yi, who was based in nearby Shantung Province. Chen Yi’s forces had been freed for the Huai-Hai campaign the previous month with his seizure of Tsinan, the capital of Shantung Province. Tsinan fell on September 24 after eight days of continuous fighting when the Nationalist Eighty-fourth Division, under General Wu Hua-wen, guarding the western sector, defected, opening a gap that allowed a tank-led Communist column to penetrate the city walls and overwhelm the 110,000 troops of the defending garrison. Prior to the Communist attack, determining that Tsinan was indefensible, General Barr had advised Chiang Kai-shek without success to withdraw its garrison into Hsuchow.

The other major prong of the Communist offensive was to be the Central Plains Field Army of 130,000 troops, commanded by Liu Bocheng, the famous “One-Eyed Dragon.” For the Battle of the Huai-Hai, the armies of Chen Yi and Liu Bocheng were better armed than in past campaigns, having received Japanese arms made available by the Russians in Manchuria as well as American equipment captured from the Nationalist armies there by Lin Biao. For the first time the Communists deployed a special tank column, which included American-made Sherman tanks captured from the Nationalists and Japanese light tanks turned over to them by the Russians. Initially, while learning to operate the tanks, the Communists pressed captured Japanese and Nationalist tank crews into service.

As the Communist armies trained and grouped for the attack, Chiang Kai-shek met with his generals on November 4 to 6 to plan the defense strategy. His senior military commanders pressed for the withdrawal of troops from the Hsuchow salient to a defense line south of the Huai River. American advisers were of the same view. Chiang initially offered command of his troops for the impending battle to General Pai Chung-hsi, the Central China commander, widely regarded as the ablest of the Nationalist generals. When Pai insisted with other generals on a defense line along the Huai River, Chiang decided that he would direct overall operations himself from the Ministry of National Defense in Nanking. He gave field command to Liu Chih, regarded by many military observers as a very weak general pliant to Chiang’s every wish, and as deputy appointed Tu Yu-ming, one of the generals held responsible for the Nationalist debacle in Manchuria. On November 25, as General Barr received intelligence on the concentrations of the Communist armies, he became alarmed. He urged the Generalissimo to withdraw the Nationalist divisions holding the exposed Hsuchow salient to a new defense line farther south. Chiang demurred and made the fateful decision to confront the Communists armies on the Huaipei Plain. With his unopposed air force and American-equipped and -trained divisions, he gambled that his forces could trap and destroy the advancing Communists columns. To engage the Communist armies, Chiang arrayed more than half a million of his troops in six army groups north of the Huai River, hinging their defense line on the Hsuchow salient.

On November 25, I flew with other foreign correspondents on a Nationalist Air Force C-47 transport to Hsuchow. Our pilot was Lieutenant Joseph Chen, who was to become a Nationalist hero on Taiwan in 1958 when, leading a squadron of U.S.-supplied F-86 Sabres, he would shoot down a Communist MIG with a Sidewinder missile in a dogfight over the Taiwan Straits. Our transport circled over the Huaipei battlefield just after the Communists, employing their classic encirclement tactics, reaped their initial success. Attacking on a broad front, the armies of Chen Yi and Liu Bocheng pinned down the Nationalist divisions, commanded by General Liu Chih, which were strung out in fixed positions to the east and west of Hsuchow. One of Chen Yi’s fast-moving columns then snapped a pincer around the town of Nienchuang, thirty miles east of Hsuchow, which was garrisoned by ten Nationalist divisions of the Seventh Army Group under the command of General Huang Pai-tao. A Nationalist armored column commanded by the Generalissimo’s son, Colonel Chiang Wei-kuo, dispatched from Hsuchow to the relief of besieged Nienchuang, was blocked and immobilized by Chen Yi’s troops twelve miles west of the town. The Communists broke into Nienchuang after two of Huang Pai-tao’s generals defected to the Communists with three divisions. Huang committed suicide, and only about 3,000 of his 90,000 troops managed to break through the Communist encirclement to the protection of the Nationalist armored relief column. From our transport, circling before landing on an airfield within the Hsuchow perimeter, I looked down on the smoking ruins of Nienchuang. Corpses and abandoned equipment lay throughout a network of trenches radiating from the edge of an outer moat. The Communist tank-led assault had penetrated two brick and mud concentric walls and moats in overrunning the town. Sorties flown in support of the defenders by Nationalist bombers and fighters failed to beat back the attackers.

We circled over Hsuchow to learn whether the airfield was secure before landing there. The city was laid out in a hilly region on the shores of the large Dragon Cloud Lake. Strategically located, it had been the site of many great battles fought during its 2,500-year history. It was a city revered for its rich cultural heritage dating from the Han dynasty (202 B.C.–A.D. 220). But savoring its culture by visiting the nearby imperial Han tombs was not our interest when we landed in the Communist-besieged city whose defense perimeter was being raked with artillery fire. The city was totally disheveled, its rows of dilapidated two-story buildings jammed with refugees, the hospitals filled with untended wounded, the airfield crowded with panicky civilians mobbing and bribing pilots to be given seats on outgoing transports.

At the Nationalist headquarters, our party of correspondents was loaded into a truck and driven over the rutted roads to the perimeter as artillery shells fired by Nationalist batteries whined overhead, targeted on the Communist forces in the outskirts. We were taken to a perimeter village where a Communist thrust had been repulsed nearby during the night. The bodies of some twenty Communist soldiers lay in a field. The bodies, lashed behind ponies and the bumpers of trucks, had been dragged in from the outlying Nationalist entrenchments. In their yellow padded tunics and leg wrappings, the dead men, their features gray and frozen, looked no different from the Nationalist soldiers gathered about us. Some of them had been shot in the back of their heads. When Henry Lieberman, the correspondent for the Times, asked about these executions, a Nationalist officer only shrugged. There were no adequate medical facilities for the Nationalist wounded, certainly not for Communists found on the battlefield.

The next day, we left Hsuchow bound for Shanghai on one of General Claire Chennault’s Civil Air Transport planes that was loaded with wounded Nationalist soldiers.* As we were leaving Hsuchow, as I would be told subsequently, Chen Yi’s columns were racing southwest from conquered Nienchuang to join with the troops of Liu Bocheng in executing an encirclement of the Nationalist Twelfth Army Group, commanded by General Huang Wei. The Nationalist group, composed of eleven divisions and a mechanized column, totaling about 110,000 men, had been ordered up from Hankow in the southwest to cover the withdrawal of the Hsuchow garrison. Chiang Kaishek, recognizing belatedly the untenable position of the Hsuchow garrison, had ordered its retreat to the cover of the Huai River line, the strategy proposed to him initially by his general staff and American advisers, which he had earlier rejected. Anticipating the maneuver, the Communists threw a blocking force of about 250,000 troops across the line of retreat to the south. Chiang then ordered the Hsuchow garrison to break out and go to the relief of Huang Wei’s Twelfth Army Group, which had been encircled sixty-five miles to the southwest. Short of food and munitions, which were being supplied by air, the Twelfth Army Group was being decimated by a ring of Communist artillery. Responding to Chiang’s order, the Sixteenth Army Group, which had been holding the southern sector of the Hsuchow perimeter, moved out on November 27 but was quickly enveloped by the Communists and surrendered after six of its regiments defected. In the engagement some 30,000 troops of the Sixteenth Army Group were killed or captured. The commander, General Sun Yuan-liang, escaped dressed as a beggar.

The following day, with his forces disintegrating, the Nationalist commander in chief, General Liu Chih, flew out of Hsuchow to the safety of Pengpu, a rail town on the southern bank of the Huai River. This was only four days after he told me and other correspondents in our briefing in Hsuchow that he would never surrender the city. He took with him the Generalissimo’s son, who turned over the command of the Armored Corps to his deputy. Two days after their flight, Liu Chih’s deputy, General Tu Yu-ming, carried through the evacuation of Hsuchow. Huge gasoline and munitions dumps around the city were blown up, sending up clouds of smoke hundreds of feet into the air. Outside the city, Tu formed up the remnants of the Hsuchow force, which included the Armored Corps and the Thirteenth and Second Army groups, into a column of some 250,000, including about 130,000 combat effectives. The column then moved south slowly, weighed down by heavy equipment. It was made up of the combat effectives, thousands of lightly armed service troops, as well as families of army officers, local officials, and students. The troops, buffeted by the sharp, cold winds of the approaching winter, marched across the desolate plain alongside American six-by-six wheeled trucks, halting at times to fight off repeated Communist guerrilla attacks on their flanks.

Having taken Hsuchow on December 1, the Communist armies of Liu Bocheng and Chen Yi pursued and struck the flanks of the retreating Hsuchow garrison, bringing it to a halt sixty miles from the city. In desperation, Tu Yu-ming, the Nationalist commander, circled the huge column into a defense perimeter northwest of the town of Yungcheng, about a hundred miles north of Pengpu, the safe haven on the Huai River to which he had hoped to escape. Trucks were emplaced along the outer rim of the perimeter, and the troops dug trenches behind them in the ice-crusted soil. The Armored Corps and artillery were sited at the center of the perimeter to lay down protective fire. Within the perimeter, pelted by freezing rain and snow, the civilians who had accompanied the column huddled in improvised shelters in an abandoned village. In desperation, Tu Yu-ming radioed the Generalissimo begging for a relief column that would enable his troops to break out of the encirclement.

Upon arrival from Hsuchow at Shanghai’s Longhua Military Airport, I became witness to another sort of mass flight. In anticipation of an imminent Communist assault on the coastal metropolis, a civilian exodus had begun. Chinese who could afford the huge ticket prices were flying out on foreign-owned commercial airliners. Along the wharves of the Whampoa River opposite the towering buildings of the Bund, housing the great trading companies, foreign banks, and the swank Cathay Hotel, all manner of small ships were taking on passengers bound for Taiwan, Hong Kong, and the southern ports. The U.S. Navy transport Banfield was lying nearby with several hundred marines aboard to aid Americans if evacuation was ordered. But at that moment most of the 100,000 foreign residents seemed somewhat less inclined than the Chinese to leave Shanghai, reluctant to forsake the easy life they had enjoyed there. At the Shanghai Club, which boasted the longest bar in the world, and at the American and Diamond bars, I spoke to British, French, and American residents, many of them women, who were ignoring warnings of their consulates to leave if they had no compelling reason to stay on. British traders, like those of Jardine Matheson, were least ready to abandon their lucrative business. The American-owned Shanghai Evening Post and Mercury carried a speech by the British consul general, Robert Urquhart, in which he told businesspeople meeting at the Country Club on Bubbling Well Road: “Shanghai is home to us as a community, not merely a trading post, and we are not going to up and leave our community home at the first signs of an approaching storm. Does anyone suggest that if there is a change of government here, the new one will be so unreasonable that they will make civilized life and normal trading impossible? I have great confidence that the government of China will not fall into the hands of any but responsible men, who will have the interests of their country at heart. And we foreigners ask for nothing more.”

The British consul general was thus keeping the colonial “stiff upper lip” despite daily signs that the metropolis of 6 million was becoming unmanageable. Overrun with desperate, starving refugees, the streets were in chaos despite the presence of thousands of troops striving to enforce martial law. The economy was disintegrating. On November 1, General Chiang Ching-kuo, one of the Generalissimo’s sons, who had been put in charge of maintaining order, had resigned his post, declaring indignantly that the city had fallen into the toils of “unscrupulous merchants, bureaucrats, politicians and racketeers.” In August, in events leading up to his resignation, Chiang had issued draconian economic reform decrees to curb currency speculation, hoarding, and black marketing. He had sternly enforced the regulations, executing some of the offenders on the streets as crowds looked on. But when his measures began to restrict the speculative business life of the city, Chiang encountered opposition from local titans. The general had the support of K. C. Wu, the ebullient, courageous mayor of Shanghai. But he ran afoul of Tu Yueh-sheng, the notorious leader of the underworld, a member of the Green Gang secret society, who was known to have political ties to Chiang Kai-shek. The irrepressible Chiang Ching-kuo also crossed his stepmother, Madame Chiang Kai-sheck. His agents discovered a huge hoard of prohibited goods in the warehouses of the Yangtze Development Corporation, controlled by H. H. Kung, the banker husband of Madame Chiang’s elder sister. Chiang’s agents raided the warehouses and threatened to arrest David Kung, the banker’s son, who was in charge of the cache. Madame Chiang flew to Shanghai, and soon after, David Kung left for the United States, fleeing any reprisal in the scandal. Restraints on prices and wages were scrapped under the pressure of the local overlords the day before Chiang Ching-kuo resigned. The value of the currency plummeted thereafter. In a stunt to stabilize the currency, the Bank of China proclaimed it would sell 40 grams of gold to each applicant at the fixed price of 3,800 yuan an ounce. Some 30,000 people, frantic to exchange their paper currency before it became worthless, rushed to line up before the bank. Ten suffocated in the mad crush. The exchange offer turned out to be only a token gesture, since the bank’s gold reserves had already been earmarked for transfer to Taiwan on Chiang Kaishek’s personal order.

In Shanghai, I filed my Hsuchow dispatches at the AP office and billeted at the Foreign Correspondents Club. The club occupied the top three floors of the Broadway Mansions, a high-rise hotel linked to the Bund by a bridge over Soochow Creek, a polluted waterway to the Whampoa River crowded with native sampans. Many of the club bedrooms were standing empty, since correspondents had begun to evacuate the city, not willing to risk being trapped in a Communist takeover. I met there with Fred Hampson, the indomitable AP bureau chief for China, who had decided to remain in Shanghai through what seemed to be the inevitable Communist occupation. Over drinks in the empty bar, I found Hampson preoccupied by how he could post a correspondent with the advancing Communist armies. At the time, there were no independent Western correspondents reporting from the Communist side. As he spoke of his frustration, Hampson dangled before me the irresistible bait of fame. I left him wondering how I could become that famous correspondent.

On my return to Nanking, I went to Harold Milks with a plan that I began to concoct on the plane, which I thought would get me back to the front and posted with the Communist forces. Tu Yu-ming’s encircled Hsuchow garrison column seemed destined for annihilation, and I foresaw a quick advance thereafter by the Communists on Pengpu, the principal town on the Huai River. I knew that there was in Pengpu an Italian Jesuit mission. My plan was to enter the mission, wait there until the Communists occupied the town, then emerge and ask the Communists to allow me to cover their advance on to Nanking and Shanghai. I envisioned myself as the sole Western reporter covering the advancing Communist troops, filing dispatches over their broadcast radio for pickup by the AP monitor in San Francisco. I also thought of seeking an interview with Mao Zedong. Recalling the friendly reception given me by the Communist leadership in Yenan in 1946, I thought I would find the Communists amenable. Milks, a seasoned midwestern newsman, listened with a trace of skepticism but nevertheless agreed. I confided also in Audrey’s father, Chester Ronning, who provided me with sage survival advice and a sack of Chinese silver dollars, acceptable currency in the Communist-held areas.

On December 12, 1949, Milks drove me in his jeep to Pukow, the terminus on the Yangtze River of the rail link to Pengpu and Hsuchow. Troop trains were arriving from the north packed with wounded soldiers and thousands of refugees. The trains were so overcrowded that some refugees came into the station clinging to the iron cowcatchers at the front of the steaming locomotives. Despite the freezing December wind, women dressed in ragged tunics over trousers, with babies on backs, sat on top of the train, beside their men folk clutching bundles of their remaining worldly possessions. One old bearded man hanging out of a vestibule was holding a straw cage filled with quacking white ducks.

Grinning soldiers in a crowded boxcar of one of the few trains going north, responding to my entreaties voiced in my poorly accented Chinese, hauled me aboard, and I found a place among them propped up against a sack of rice. The rice sacks, the soldiers told me with provocative leers, were stashed along the sides of the boxcar to afford some protection from the gunfire of Communist guerrillas who waited in ambush along the tracks. As the train jolted out of Pukow and rattled north, I peered out through a door left ajar and saw bodies of men, women, and children, looking like crumpled rag dolls, lying at the side of the tracks. Hands made numb by the intense cold, unable to hold on as they rode atop the moving trains coming from the north, they had toppled down. In the evening I gladly accepted a bowl of cold rice sprinkled with piquant sauce offered to me by a young officer. Wrapping myself in a blanket, I spent the night half awake, suffering the stench of unwashed bodies lying close together, staring into the darkness as the train jostled from stop to stop past flood-lit army blockhouses, and beginning to wonder if I had been too adventurous.

At dawn we were in Pengpu, a rude market town with a population of about 250,000 which traded the grain crops and livestock of Anhwei Province. Hoisting up my duffel, I jumped out of the boxcar into a frantic mob struggling to get on the train, which was to return south. Women were carrying or pushing frightened children into the boxcars or climbing up the side of the train to tie them to whatever metal protrusion they found on top. I followed the soldiers, who opened a path through the crowds with swinging rifle butts, to the small dingy station. There I found a rickshaw pulled by a young coolie who took me at a trot over muddied streets to the walled compound of the Sacred Heart Jesuit Mission, a cluster of about twenty buildings around a redbrick Gothic church. As I paid the rickshaw puller, I asked him if he feared the coming of the Communists. “No.” he replied. “It will be better. When the fighting stops, the rice will be cheaper.”

Welcomed by a priest into the Catholic mission, I was received by Bishop Cipriano Cassini, a kind, portly Italian in his fifties with a trim gray beard who wore a black skullcap and a large crucifix over a long black gown that swept the stone floor. His mission operated schools for the education of some ten thousand Chinese boys, a nunnery, an orphanage for abandoned infant girls, and a hospital. Cassini, who had come to China sixteen years earlier, had been appointed bishop by the Vatican in 1936. He spoke Italian, French, Chinese, and a few words of English, and we carried on our conversation in fragments of several languages. Over strong black coffee, he listened sympathetically to my plan and told me: “You are welcome to share our bread and shelter.” He readily agreed to allow me to stay in the mission, not manifesting any concern that harboring an American might someday invite Communist retaliation.

In the afternoon, I called on General Liu Chih, the Nationalist commander in chief, who had fled Hsuchow on November 28. I found him in a villa vacated by a wealthy rice merchant. The general, fleshy in a plain uniform, flashed a gold-toothed smile as he welcomed me into his map room, heated by a coal brazier. “We are closing a trap on Chen Yi and Liu Bo-cheng,” he said, pointing to his situation wall map. He had sent his Sixth Army Group, commanded by General Li Yen-nien, and the Eighth Army Group, under General Liu Ju-ming, a total force of eleven divisions, north from the Huai River line with orders to smash the Communist columns against the anvil, as his interpreter described it, of the encircled Nationalist Twelfth Army Group, commanded by General Huang Wei. The Twelfth was trapped forty-five miles northwest of Pengpu. I left Liu Chih’s headquarters less than convinced.

Two days later, on December 15, his troops decimated by Communist artillery, and after one of his twelve infantry divisions had defected, General Huang surrendered the remnants of his Twelfth Army Group. His forces compressed into a four-mile-square area, he had held out for almost three weeks. He was taken prisoner with his deputy commander, Wu Shao-chou. The next day, Liu Chih’s Sixth and Eighth armies, which had advanced only seventeen miles, came under attack by Liu Bocheng’s columns and turned back to Pengpu harassed by local Communist militia. Standing on the banks on the Huai River, I watched their tanks and truck convoys rattle back over the railway bridge, followed by long lines of weary infantry. One of the last trains arriving from the north brought a company of light tanks on flat cars which were sent south to a new defense line that was being prepared.

On December 16, I was told at the garrison headquarters that Tu Yuming’s Hsuchow column was still holding out, awaiting help from the south. The following day, the Communist radio carried a message from Mao Zedong addressed to Tu Yu-ming: “You are at the end of your rope. For more than ten days, you have been surrounded ring on ring and received blow upon blow, and your position has shrunk greatly. You have such a tiny place and so many people crowded together that a single shell from us can kill many of you. Your wounded soldiers and the families who have followed the Army are complaining to high heaven. Your soldiers and many of your officers have no stomach for more fighting. Hold dear the lives of your subordinates and families and find a way out for them as soon as possible. Stop sending them to a senseless death.” Tu Yu-ming did not reply.

On the morning of December 18, in the Sacred Heart Church, I watched more than a hundred Chinese children chanting hymns, kneeling to be baptized. Above them, in the sandbagged steeple, soldiers at the lookout post listened to the rites conducted by a Chinese Catholic nun. That afternoon, the people of Pengpu, observing that demolition charges were being placed under the 1,823-foot, nine-span bridge across the Huai River, gathered before the garrison headquarters to protest its destruction. The bridge, erected forty years earlier, had served to transform Pengpu from a mud village into a bustling commercial center by attracting trade from the countryside. When a garrison spokesman emerged to tell the townspeople that the bridge might have to be blown to hinder a Communist crossing, there were shouted protests. I heard one man call out that the bridge belonged neither to the Nationalists or the Communists but to the people. They knew how difficult it would be to repair the structure. They spoke of that day in January 1938 during the war with Japan when Chinese troops blew up the bridge to impede the advance of Japanese troops. It took the Japanese eight months to repair the bridge. The Pengpu garrison did not blow up the bridge, but the troops began on December 27 removing sections of the bridge for shipment south to Pukow, making it impassable to truck and rail traffic.

On Christmas Eve, I spoke to Harold Milks on the single telephone line out of Pengpu, dictated my dispatch, and told him if the Communists did not come soon, I would try to reach their lines by crossing to the other side of the Huai River. That night, Milks sent a brief dispatch describing me as “the loneliest Associated Press staff member in the whole world this Christmas eve.” By wondrous chance, Audrey read the dispatch in Vancouver, where she was attending the University of British Columbia. Strolling with a friend along a Vancouver avenue, she saw a rain-sodden newspaper lying on the sidewalk with a large headline about the China Civil War. Picking it up, she spotted the box, written by Milks, at the bottom of the front page describing my lonely Christmas vigil in Pengpu.

In fact, I was not all that lonely. That afternoon at the railway station I ran into three newly arrived British newsmen. They were Patrick O’ Donovan of the Observer, Bill Sydney of the Daily Express, and Lachie MacDonald of the Daily Mail. To welcome them suitably I shopped at a Chinese provision store and was delighted to find a bottle of Johnny Walker Black Label Scotch, for which I paid the equivalent of twenty dollars. In a bedroom of the mission, portraits of the saints looking down on us, I doled out the scotch into tea mugs. With cheers we downed the precious drink and then in unison spat on the flagstones. I had been taken. The bottle had been filled with stale tea and resealed. We managed, nevertheless, a Christmas drink with a bottle of Italian red wine contributed by an obliging priest. I accompanied O’Donovan, a burley Irish Catholic man, to midnight Christmas mass, during which he knelt in prayer beside Chinese worshipers and received the sacrament from the bishop. The unheated church was draped in festive red cloth and crowded with about two hundred worshipers, mostly Chinese, who came carrying bedding, since they intended to stay the night. The town was under curfew, and edgy sentries were patrolling the snow-covered streets. Before the altar an Italian priest set up a large book of Christmas music, verses rendered in Chinese characters, and led the congregation in singing “Adeste Fideles.” Christmas dawned to the sound of random shooting in the town.

On Christmas Day, Liu Chih sent a message urging us to leave Pengpu aboard his train. The Huai River line was not to be defended, and he was moving his headquarters south. My companions of the night decided to depart with him, and I went to the railway station to say good-bye. I watched them leave on an armored train with tank turrets affixed atop the cars, the locomotive pushing an open steel-plated car manned by machine gunners. I then felt very alone.

Growing impatient, I decided on New Year’s Day to cross the Huai River and hike north to the Communist outposts. After being told twice by the garrison commander that I could not cross the river, I managed to negotiate a pass from a Nationalist officer who was beyond caring about the activities of a crazy American. A priest found two railway workers, eager to return to their homes north of the river, who agreed to carry my baggage. Dressed in a U.S. Army pile jacket and a brown wool hat, I set out 0n the morning of January 2 followed by the railway men bearing my duffel between them on a yo-stick, the quintessential bamboo pole. At the railroad bridge, an army lieutenant checked my papers, looked me over curiously, and then escorted us on the pedestrian walk across the span to the last outpost at Tsaolaochi, ten miles north of Pengpu. Beyond, he warned, lay no-man’s-land, ruled by bandits who preyed on travelers. Unarmed, we would be vulnerable until we reached the first Communist outpost. North of that outpost, the Communists were in control of all the Huaipei Plain except for the flaming perimeter held by the Hsuchow column, ninety miles to the northwest of Tsaolaochi.

As we began walking along the abandoned Pukow Railroad, Nationalist Air Force planes droned overhead on the way to drop supplies to Tu Yuming’s troops or strike at the encircling Communists. About five miles out of Tsaolaochi, we saw a barrier across the road controlled by men with guns. A peasant coming from the barrier mumbled something about “bad men.” Bandits, I thought apprehensively. The armed men had seen us, and so it was too late to turn back. There were four of them in peasant dress. A sharp-faced man, oddly wearing a crumpled gray fedora, pointed an American Thompson submachine gun at me. When I asked him in Chinese, “Who are you?” he shouted back, “Who are you?” and thrust his gun at me. “I am an American correspondent,” I said. He did not seem to understand and angrily shouted again: “Who are you?” He slipped the safety catch on the Tommy gun, and, as if in a trance, I watched his fingers wrap around the trigger. One of my baggage carriers cried out, “He is an American correspondent.” The sharp-faced one lowered the gun and searched us for weapons. Suddenly, two soldiers in uniform stood up about 150 yards from the barrier. They had been covering the roadblock with a machine gun. We were in the hands of Communist militia. I showed a letter written in Chinese to one of the uniformed militiamen. It identified me and asked clearance to proceed to the headquarters of Mao Zedong for an interview. I also showed him a photograph taken of me posing with Liu Shaoqi, Zhu De, and other Communist leaders at the dinner in Yenan. The militiaman, a broad-faced peasant with a pistol strapped around his waist, looked blankly at the photo and the letter and shrugged.

Escorted by a half dozen militia riflemen, I was taken with the railroad men on a long march to a village where the militia headquarters was located. It was the area in which Nationalist general Liu Chih’s Sixth and Eighth Army groups had come under attack by the militia during their futile effort to reach the encircled Twelfth Army Group. Decomposed bodies of soldiers still lay in the fields or in slit trenches and foxholes picked at by village dogs and flocks of cawing ravens. Peasants were fashioning mud bricks to rebuild walls and thatch roofs on houses smashed by artillery fire. Trees, once carefully husbanded near each cluster of huts, had been cut down during the fighting to clear fields of fire. We passed scores of wounded Nationalist soldiers, whom the Communists had released farther north, limping back to their homes in the south.

At the headquarters, the militia chief told me of their victory. Proudly, he thumped his chest with the flat of his hand as he also trumpeted that the peasants of the region now owned the land and the landlords had been dealt with. He spoke of the coming of Communist comrades many months before the Battle of the Huai-Hai. The village, like others on the Huaipei Plain, had slumbered without a dream of change until Communist cadres coming from North China and Shantung Province suddenly appeared. In teams made up of about a half dozen cadres, some of them students, they visited the villages, where they entered into discussions with the peasants about their grievances. Nothing was said about Marxist-Leninist ideology. The cadres heard complaints about corrupt officials and the local landlord gentry who owned about one-fourth of the land. Laws restricting rents to 37.5 percent of the crop tilled by tenants were not being respected, and there were landlords who charged as much as 60 or 70 percent. Some of the gentry, called “Big Trees” by the Communists, behaved as petty despots, their men beating peasants who failed to pay their rents or the usurious interest charged on loans. It was not uncommon for a landlord to take the daughter of a peasant who failed to pay his rent as a slave maid or a concubine. Village officials deferred to the landlord “Big Trees,” and there were no restraints imposed by the provincial government as long as taxes were paid. Bolstered by the presence of the newly arrived Communist cadres, the peasants organized violent demonstrations against the ruling gentry. In the village where the Communist militia headquarters was now located, a landlord who owned more than 50 acres was denounced, humiliated at a trial, and stripped of his holdings. At a neighboring village, a landlord accused of killing one of his tenants was stoned to death. The middle peasants who tilled their own soil were left undisturbed, but all large landholdings were seized and distributed by the cadres to poor families, each adult receiving about one-third of an acre. Several weeks after the arrival of the party cadres, the first Communist army units came into the villages. The soldiers paid for their food, unlike the Nationalist troops, who angered the peasants by requisitioning supplies. Peasants were formed into so-called self-defense units. In the fall of 1948, when Chen Yi and Liu Bocheng’s columns entered the region to make ready for the Huai-Hai campaign, hundreds of villagers were ready to carry supplies and dig trenches across roads to slow the movement of Nationalist troops. When I asked the local militia leader how his men had been able to do battle against tanks and artillery of Liu Chih’s Sixth and Eighth army groups, he said: “These are our fields.”

What had transpired in the militia leader’s village illustrated how the Communists gained mass peasant support in many regions of the country. The indifference of the Chiang Kai-shek government to the plight of the poorer peasants provided fertile ground for Communist inroads. In June 1946 the Nationalist government had reintroduced a land tax, which was so indiscriminately administered that it aroused anger and despair among the poorer peasants. To support its military operations, the government also increased requisitions of grain despite warnings by provincial authorities that peasants in desperation were being driven to uprisings, banditry, and flight to the towns and cities. Belatedly, only when the Communists were on the brink of victory did the Nationalist government begin to seriously consider land redistribution programs designed to attract peasant support, but only token efforts were made.

During the Civil War the Communist land reform policies fluctuated with the tides of battle and were not implemented in either a uniform or orderly manner, particularly in the treatment of the landlords and the middle peasants. In travels to regions other than the Huaipei Plain, I spoke to Chinese who had experienced rampant terror, especially in Hopei and Shantung provinces after the issuance of the May 1946 decree by the Communist Politburo on land redistribution. Hundreds of thousands of landlords and at times also middle peasants were denounced, deprived of their land and goods, and many were stoned or beaten to death in the mass “speak bitterness” struggle sessions. The peasants were incited by party cadres of “leftist tendency” who did not heed the more moderate policies instituted later, which granted landlords not convicted of “crimes against the people” the right to retain land on the scale of the average holdings and guaranteed protection to middle peasants who tilled their own fields. In instances in which Nationalist troops reoccupied areas where the Communists had carried out land redistribution, the returning landlord “Big Trees” often wreaked the most brutal vengeance on peasants who had supported the Communists.

In later years, recalling the passion of the militia leader in the Huaipei village, I wondered whether the peasants who had rallied to the Communists felt cheated when Mao collectivized their independent landholdings in 1952 and in 1958 herded them into giant People’s Communes. Two years after Mao’s death in 1976, the communes were completely dismantled. Under Deng Xiaoping, who had become China’s paramount leader, peasants were given plots of land on thirty-year leases to farm in a relatively free market economy. Millions of peasants were lifted out of absolute poverty. But then the Huaipei militia leader would be shocked to know that, following Deng Xiaoping’s reforms in the early years of the twenty-first century, Communist police would be beating and incarcerating peasants who were taking part in thousands of rural demonstrations protesting their exploitation by corrupt local officials, arbitrary seizure by developers of their allocated land, and industrial pollution of their environment.

My first night in the “Liberated Areas” was spent at the militia headquarters in a mud-walled shed, where I stretched out on sacks of kaoliang (sorghum) grain. With rats scampering about, I pulled my wool knit hat down over my chin and during the night endured several rodents treading across my covered face. I was glad to see the morning and the militiaman who brought a feast of fresh hen’s eggs, steaming hot brown kaoliang bread, and tea.

We marched north all the next day but stopped, at my request, at the village of Chungchou, where there was a Farmer’s Bank, where I exchanged one of the silver dollars given to me by Ronning for 200 yuan of the Communist-issued currency. At sundown we came into a village where I was greeted by the commander of a unit of General Liu Bocheng’s columns. It was my first contact on the Huaipei Plain with a regular army unit. The commander, who wore no badge of rank or unit identification, was a lean, powerfully built man with a friendly, compassionate manner about him. “We will escort you to Suhsien,” he said. “You will go by horse tomorrow.” He released the railway men who had accompanied me, telling them they could go wherever they liked.

The next morning, on horses led by one mounted rifleman and with another militiaman leading a horse laden with my baggage, we rode out of the village, passing through a cluster of boys with shaven heads staring wide-eyed at the first “foreign devil” they had ever seen. The commander waved good-bye. I would see him again and come to like him more than anyone else I met on the plain. We rode well away from the railroad so as not to risk being strafed. Nationalist fighters and bombers passed overhead on the way to or returning from the encirclement of Tu Yu-ming’s Hsuchow column, seventy miles to the northwest. Each village seemed like the other as our horses picked their way across the monotonous plain, following paths through the fields and along the banks of irrigation ditches. At a village in which we stopped for the night, I shared a hut with my escort and soldiers who played cards and sang at fireside. One of the songs referred to Chiang Kai-shek as “a running dog of the Americans,” and with a grin, one of the soldiers asked in a friendly fashion: “Why is Truman helping Chiang?” I simply smiled and shook my head. In the morning I was awaken by soldiers drilling outside the hut and singing: “On to Nanking and strike down Chiang Kai-shek.” Speaking later to the soldiers in the campsite, I listened to them repeating the litany of political commissars who promised liberation of their families from ruthless landlords and corrupt Kuomintang village officials. I never heard any references to Marxist-Leninist ideology. At one meeting the common soldiers were being briefed by an officer on the strategy of the campaign. It was this sort of indoctrination by many thousands of political commissars which cemented the loyalty of the sons of peasants serving in the Communist armies. Nothing like it, as far as I knew, was done in the Nationalist forces.

We rode on the next day, and our journey took us through the eastern edge of the battlefield where General Huang Wei’s Twelfth Army Group had been destroyed three weeks earlier. The battlefield was deserted and silent, except for the cawing of ravens perched on human body parts. The fields had been cratered by artillery fire. Demolished American-made vehicles, stripped of parts, lay half buried. Huang and thousands of his troops had been marched off to prisoner encampments in long lines. I saw no one mourning or caring for the fallen, their bodies lying in fields illuminated by the golden glow of a setting sun. The shrunken face of one of the dead sprawled beside the road, his body sniffed at by village dogs, haunted me for years. My escort told me that Liu Bocheng and Chen Yi’s conquering divisions had marched north to join the encirclement of Tu Yu-ming’s forces.

At dusk on January 5, we reached what was apparently the main field Communist headquarters, about ten miles southwest of Suhsien. Artillery fire could be heard from the nearby battlefield where the Hsuchow column was dug in encircled by some 300,000 Communist troops. I was taken first by my escort to a hut where I waited until a man named Wu, addressed as “Deputy Commissar” but dressed like the soldiers in a plain uniform without insignia, arrived and questioned me in Chinese. He was obviously a sophisticated, well-educated man but hard-faced and suspicious. When I tried to engage him with pleasantries, he would tell me nothing about himself except that he was from Hopei Province. “I cannot take responsibility,” Wu said, “for allowing you to pass into the Liberated Area. Your case must be referred to my superiors.” He left with my letter requesting that I be permitted to proceed to Mao’s headquarters for an interview with the Communist leader. I was escorted to another peasant hut with a grain shed, in which I slept restively that night listening to the thud of nearby artillery fire. At dawn, I found myself under the guard of three soldiers, all armed with American carbines. They permitted me to walk out into bright sunshine. Out of a clear sky, a Nationalist fighter swooped down on a strafing run, its machine gun fire stitching across a nearby field. It did not occur to me to duck for cover, nor did it excite my guards, who presented me with a breakfast of duck eggs. All through that day, and into the night, I heard the heavy thudding of artillery fire. Then, at dawn, the guns fell silent. When I tried to leave the hut to learn what was transpiring, one of the guards blocked my way.

In the late morning, Wu entered the hut where I had spent the night and told me firmly: “In regard to your mission we ask you to return. This area is a war zone and it is not convenient for you to proceed.” I interjected: “But if it is a question of danger, I don’t care.” Wu snapped back: “You don’t care, but we do care about you passing through here.” Shaken, I turned and walked into the grain shed and in frustration beat my fist against the sacks of grain stalks. When composed, I returned to face Wu. I asked if I could proceed via Shantung to Tsingtao, where U.S. Marines were based. He declined. When I asked for an explanation in writing, he shook his head and said: “It is enough that you have asked and we have refused.” He said he did not know whether my request for an interview with Mao had been referred directly to the Communist leader. Stung by Wu’s hardness, I said bitterly: “You know I came here to tell your side of the story.” Wu’s features relaxed. “You cannot help us,” he said softly and then shaking his head impatiently added firmly: “The horses are outside the door.”

In front of the hut there was an escort officer and two soldiers already mounted. Wu returned my typewriter and camera, taken from me when I arrived. As I mounted my horse, Wu came up beside me, put his hand on the saddle, and said gently, speaking in English to me for the first time. “I hope to see you again. Peaceful journey. Good-bye.”

As we rode out of the village, there was no sound of gunfire, only an eerie stillness. I said to the escort officer: “Are the Hsuchow troops finished?” “Yes,” he replied. “Just about finished.” It was January 7. In the next days as we rode back toward the Nationalist lines, the escort officer told me what had taken place within the encirclement and was later detailed on the Communist radio. Tu Yu-ming did not reply to Mao’s December 17 message, in which Mao guaranteed life and safety to all if he would surrender. Thereafter, conditions in the Nationalist camp steadily worsened. Airdrops by Nationalist transports made from above two thousand feet could not meet the needs of the thousands of trapped military and civilians. Two-thirds of what was parachuted drifted into the hands of the Communists. Horses were slaughtered for food. Soldiers scrounged for bark and roots in the fields. Lacking fuel for fires, women and children froze to death in crowded huts. Communist loudspeakers along the perimeter offered food and safety to the Nationalist soldiers if they would surrender. Panic spread among the Nationalist troops when word circulated that Chiang Kai-shek might order the bombing of the Armored Corps so the tanks would not fall into Communist hands. Just before the final artillery barrage opened on January 6, the loudspeakers boomed out: “There is no escape.” The Second Army Group was the first to surrender, then the Thirteenth, and finally the Armored Corps. By January 10, the Communists had rounded up the last of the fleeing Nationalist soldiers. The Battle of the Huai-Hai ended with the capture of Tu Yu-ming, the commander of the encircled Hsuchow column, who attempted to escape in the uniform of an ordinary Communist soldier. His deputy, Li Mi, managed to escape. I later came upon him in Burma, where he was involved in a secret American Central Intelligence Agency operation. Tu Yu-ming survived as a prisoner and after the Civil War was granted comfortable retirement by the Communists, as were many other Nationalist officers. Lieutenant Colonel Chen, who piloted the plane that took me to besieged Hsuchow, was permitted to return from Taiwan and resettle in Peking. I encountered him by chance in 2003 at his well-furnished apartment, brought there for drinks by our friend, his American daughter, Rose Chen. “You must be one of the American correspondents I took to Hsuchow,” he exclaimed when I entered his Peking apartment, and we embraced.

On the journey back to Pengpu with my soldier escort, we followed the same line of villages. In every village the nights were alive with high-spirited soldiers singing patriotic songs. All seemed to have been briefed on the general strategy of the campaign and the impending assault across the Yangtze. The October 10 statement of Mao Zedong that it would take one more year to completely defeat the Nationalists was widely quoted. In one village, soldiers intensely curious about American technology crowded around when I demonstrated my typewriter and camera. One of them asked about automat restaurants in the United States. “Twenty years after all China is Communist, we shall have automat restaurants,” he said. (It was this quote in the stories I wrote about my trek across the Huaipei Plain upon my return to Nanking that seemed to evoke the most interest in the United States.) Thinking of that soldier as I write: If he survived, what fun it would have been to observe his reactions to the present-day skyscrapers of Shanghai.

That first night on my return journey I lay awake in my hut, tossing about, unable to sleep, dejected by the rebuff at the Communist headquarters. Staring into the darkness, the spell of my trek across the Huaipei Plain fading, I began to accept that my venture had been out of time and place. The era of easy mixing of Americans with the Communists such as in Yenan during the days of the Dixie Mission and the Marshall negotiations in Chungking was ended. There would be no more jovial dinners with exchanges of toasts or friendly ideological debates. We were beyond that crossroads. Mao Zedong was bent on his revolutionary course, and he would not be diverted by American influence, or for that matter, by the Russians. When will we talk to each other again? I wondered.

We made seventeen miles the next day, and we were back at the headquarters of the sympathetic commander of one of Liu Bocheng’s units. Sitting before a campfire, the commander asked me about the two-party system and the status of blacks in the United States. He told me he had been with the Communist forces since 1936 and had seen his wife and family only once since then. In the morning before I left, the commander wrote on the flyleaf of my diary in fine Chinese characters. “We would like to fight to the end with our American friends for democracy, freedom and happiness.” He signed his name Tian Wuzhang without indicating his rank. Another day’s journey and we were within five miles of the Huai River Bridge. My escort found two peasants to help with my baggage, and waved good-bye. I approached the Nationalist outpost at the bridge holding up a white handkerchief, and they took me in. I stayed the night in the Jesuit mission, said goodbye to the bishop in sadness, knowing that the Communists in occupation of Pengpu would never tolerate the mission for very long, particularly Jesuit schooling of the children. At the railway station, I forced my way into a boxcar packed with refugees and Nationalist soldiers who had discarded their weapons. On January 12 I was back in Nanking, where for the first time I was able to file to the AP my account of the final phase of the Battle of the Huai-Hai and my journey across the Huaipei Plain. I also reported from Nanking that Nationalist troops had evacuated Pengpu on January 16 after blowing up its railroad bridge, so treasured by the people of Pengpu, and looting the shops. A new defense line was established thirty miles north of Nanking.*

For the Communists, the Huai-Hai campaign lasted sixty-five days in a deployment of swift movement and entrapment of segments of the Nationalist armies. They had suffered 30,000 killed in combat. But in what was the most decisive battle of the Civil War, the Communists had achieved total victory over a Nationalist force of roughly their own size but better equipped and in complete control of the air. They succeeded in eliminating fifty-six Nationalist divisions, including some of Chiang Kai-shek’s best American-equipped and -trained troops and the Armored Corps, altogether comprising 555,000 men. The Communists took 327,000 prisoners. At least four and a half Nationalist divisions defected to them. The military equipment captured, much of it American, was beyond counting. The battle was the final blow that shattered the Nationalist Army. As I had observed in Manchuria, the Nationalist disaster on the Huaipei Plain stemmed directly from Chiang Kai-shek’s strategic miscalculations. Rejecting all advice, he had elected to stand before the vulnerable Hsuchow salient, exposing his armies to piecemeal destruction. In selecting his field commanders, Chiang appointed generals personally loyal to him, rather than the most competent. Defeat became inevitable even before the first shots were fired on the battlefields. The way was now open, as Mao had predicted on October 11, for an attack across the Yangtze on Nanking, Chiang’s capital, and Shanghai. It was the turning point of the Civil War.