On the morning of March 18, 1969, Cambodia was shaken by sixty B-52 carpet bombings, forty-eight in the border region and twelve farther inland. The previous bombings by American tactical aircraft, which had been carried out intermittently since 1965, had failed to rid the Cambodian border region of North Vietnamese and Vietcong bases and safe havens. Communist cross-border raids had been very costly to South Vietnamese and American forces. President Nixon in response ordered the deployment of the long-range B-52s, which carried huge bomb loads, for strikes at areas where the Communist units were thought to be based. While the bombing by tactical aircraft had struck narrowly at suspected targets, the carpet bombing by the B-52s now devastated entire localities. The principal intended target was COSVN, believed to be the mobile command and control headquarters for Communist operations in South Vietnam.

In the first B-52 bombing foray, the pilots reported, from altitudes of about thirty thousand feet, that they had observed explosions which could have been ammunition and fuel depots. When a Daniel Boone reconnaissance team, of two Americans and eleven Vietnamese, landed by helicopter in an area where COSVN was thought to be operating, the team came under heavy fire, indicating that the carpet bombing had been less than totally effective. Five members of the team were killed and the leader wounded. The survivors were picked up by another helicopter in a hasty evacuation. COSVN—possibly consisting, in my view, of not much more than radios and maps in knapsacks carried by sandal-shod bearers moving from straw-thatched hut to hut—continued to be an elusive target.

The B-52 bombings were carried out covertly. The secrecy was such that William Rogers, the secretary of state, was excluded from the “need-to-know list” of American officials. On March 26 the New York Times reported that B-52 raids on Cambodia’s Svay Rieng Province had been under consideration at the request of General Creighton Abrams, who the previous June had replaced Westmoreland. I was then supervising the Indochina coverage as foreign editor of the Times. The short article also stated that there were high State Department officials strongly opposed to the bombing. Among them were members of Henry Kissinger’s own staff: Anthony Lake, who had served in Vietnam, Roger Morris, and William Watts. Eventually, the three resigned in protest. When questioned by a Times reporter, the presidential press secretary, Ronald Zeigler, said he knew of no such Abrams request reaching the president’s desk. In fact, such a proposal had been made by Abrams to the Pentagon, which had then been referred to the White House. The bombings were staged after American intelligence officials thought they had pinpointed the location of COSVN in the Cambodian mid-border region, to the northwest of Saigon, west of An Loc, which had been designated as Base Area 353 and dubbed the Fishhook. Targets were selected on a basis of information received from a Vietcong deserter and aerial photographs.

The Times broke the story of the bombings on May 9, in a front-page article by William Beecher, the military correspondent in the Washington bureau. He reported that “American B-52 bombers in recent weeks have raided several Vietcong and North Vietnamese supply dumps and base camps in Cambodia for the first time, according to Nixon Administration sources, but Cambodia has not made any protest.” Beecher reported that “Cambodian authorities were cooperating with American and South Vietnamese military men at the border, often giving them information on Vietcong and North Vietnamese movements.” Evidently, the Vesuvius compact in some form was still operative, although the bombing had been extended from northeastern Cambodia to inhabited areas in the south in violation of the condition which Sihanouk contended he laid down at his 1968 meeting with Bowles. With an estimated fifty thousand North Vietnamese and their Khmer Rouge allies now in occupation of possibly one-third of Cambodia, Sihanouk, frantically looking westward for help, apparently was amenable to the bombing. Four months after the first B-52 bombing raid, Sihanouk restored diplomatic relations with the United States. In exchange he received a pledge that the United States would “respect Cambodia’s independence and sovereignty within the present territorial borders.” Yet still playing both sides against the middle in his struggle to preserve the integrity of his country, Sihanouk retained covert relations with Hanoi, hoping to limit North Vietnamese infiltration of Cambodian territory.

Beecher’s exclusive story on the bombings did not at first raise a great furor. It was, however, one of a series of news breaks traceable to government leaks that spurred Kissinger into ordering FBI wiretaps as a means of identifying the sources. Four journalists and thirteen government officials became the targets of the wiretaps. As to just how he obtained his story, Beecher broke a silence of thirty-six years when he spoke to a Harvard seminar in 2006. Reasoning that B-52 bombings had been carried out in Laos and in Vietnam along the Cambodian border, he laid out speculative scenarios for similar attacks against Communist base areas within Cambodia and presented them for comment to White House and State Department officials. He pieced together his story from what they told him and more substantively from what they would not deny. Commenting on Henry Kissinger’s contention that the bombing operation was kept secret to safeguard American lives, Beecher observed during his seminar: “From whom was it secret? Not from the North Vietnamese on whose heads the bombs were falling. Not from officials of the Cambodian and South Vietnamese governments. It was a secret only from the Congress and the American public.”

In January 1970, Sihanouk left Phnom Penh, accompanied by his wife, Monique, for a cure at a clinic on the French Riviera. He went from there on to Moscow to mend relations with the Soviet leaders, disrupted after their earlier snub of him. In his absence, in early March, Lon Nol, the defense chief, acting in tandem with Prince Sirik Matak, issued an ultimatum to the North Vietnamese and Vietcong infiltrators: Leave Cambodia or face attack. He also rallied anti-Vietnamese demonstrations across the country. Demonstrators destroyed the Vietcong and North Vietnamese diplomatic missions in Phnom Penh. Prince Sirik Matak shut down the smuggling from Sihanoukville of food, medicines, and other supplies to Vietnamese Communist units in the border areas, which had been carried on with the connivance of Cambodian army officers. Sihanouk had agreed to this smuggling operation, dubbed by American officers as the “Sihanouk Trail,” in 1966 at the request of Premier Zhou Enlai when the American blockade of the Vietnamese coast and bombing of the Ho Chi Minh Trail were impeding deliveries by the Communists to their units in South Vietnam. Prince Matak then joined with Lon Nol in signing a decree ousting Sihanouk from power. The conspirators, who were in close touch with the sympathetic U.S. Embassy in Phnom Penh, cited Sihanouk’s toleration of the Vietcong and North Vietnamese bases as one of the reasons for the coup.

Sihanouk was at the Moscow airport en route to Peking on March 18 when Soviet premier Alexei Kosygin, who was there to bid him farewell, informed him that he had been deposed by Lon Nol. When the Cambodian leader arrived in Peking, Zhou Enlai was waiting for him with a pledge of Chinese support if he would commit “to fight to the end.” Sihanouk agreed. On March 21, Premier Pham Van Dong of North Vietnam flew to Peking to confer with Sihanouk on the prince’s request. Secretly, they worked out an alliance providing for two thousand so-called advisers to be assigned to train and arm pro-Sihanouk guerrillas and the allied Khmer Rouge, use of Hanoi’s supply network to deliver Chinese arms, and joint Cambodian–North Vietnamese military operations against Lon Nol’s forces. Sihanouk told Wilfred Burchett, the leftist Australian journalist, that Pham Van Dong had given him an assurance that after victory Cambodia would be “independent, neutral and free of any Vietnamese presence.” When Burchett told me later in the year of this compact, I thought back twenty years to the time when the young Sihanouk had told me that if Ho Chi Minh triumphed in Vietnam, the Communists would set up a puppet regime in his capital.

Sihanouk never forgave the Russians for continuing to maintain their embassy in Phnom Penh, where Lon Nol was in control, while refusing to recognize his government in exile in Peking. While living in Peking, Sihanouk conspired with the “Center,” the leadership group of the Khmer Rouge, headed by Pol Pot, to gain its help in returning to power. He lived as a pampered guest in a garden villa of the old French Embassy compound, which had been taken over by the Chinese Foreign Ministry. I last saw him during a visit to Peking in 1971 at a banquet in the Great Hall of the People in honor of the visiting Communist boss of Romania, Nicolae Ceau escu. Sihanouk was chatting with Mao’s wife, Jiang Qing, when the military band struck up his composition Nostalgia for China.

escu. Sihanouk was chatting with Mao’s wife, Jiang Qing, when the military band struck up his composition Nostalgia for China.

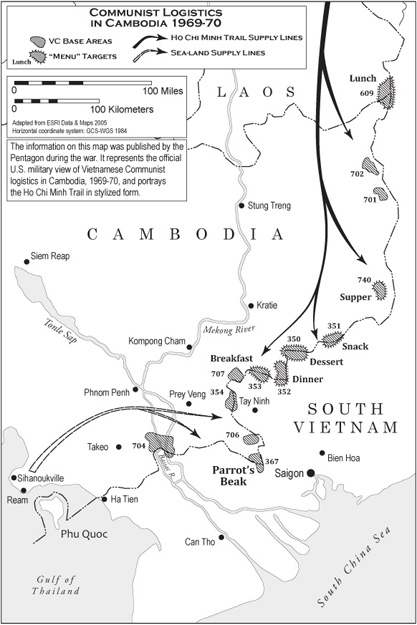

The B-52 bombings begun in March 1969 of suspected North Vietnamese positions in Cambodia continued in what was code-named the “Menu Campaign.” They were directed mainly against targets in the border region but were gradually extended much deeper into Cambodia, largely in the southwest. The Menu Campaign, initiated with the March 18 strike, which was code-named “Breakfast” —and the strikes that followed, “Lunch,” “Supper,” “Dinner,” “Dessert,” and “Snack”—ended in May after Lon Nol assumed power in Phnom Penh. A total of half a million tons of bombs were dropped.

In April 1970, the Nixon administration was confronted with these realities: The bombing campaign had failed to halt North Vietnamese infiltration into Cambodia. The military installations held by Lon Nol, now openly an American-supported ally, had come under attack by powerful North Vietnamese and Khmer Rouge forces. The Communists held five Cambodian provinces in the northeast. The Paris Peace Talks with Hanoi were stalled, and antiwar sentiment in the United States was mounting. At this juncture Nixon decided to invade Cambodia. In a television speech on the evening of April 20 he told the American people, masking the B-52 bombings and the incursions by U.S. Special Forces and those by South Vietnamese troops, that the United States had scrupulously respected Cambodia’s neutrality. But now, an offensive by the Communist forces was threatening to take over the country, and the “will and character” of the United States was being challenged. He portrayed the Communist offensive as a lasting threat to the implementation of his program of “Vietnamization,” under which American troops would be withdrawn in increments from Vietnam as their ground combat duties were handed to South Vietnamese forces. Nixon revealed that a joint American–South Vietnamese thrust into Cambodia was already under way with the aim of clearing out the North Vietnamese sanctuaries and destroying COSVN, which he described as the key control center for the Communist forces in South Vietnam. Once these objectives had been attained, he said, U.S. troops would be withdrawn.

Several hours before Nixon spoke, the invasion had begun with a spearhead of twelve South Vietnamese (ARVN) infantry and armored battalions totaling about 8,700 men crossing the border and attacking Communist border positions along the flanks of the Parrot’s Beak, to the south of Fishhook. Three days later, “Operation Rock Crusher” was launched with eight American and six ARVN battalions crossing into Cambodia. A task force of 10,000 American troops and 5,000 ARVN, including armored units and mechanized infantry, penetrated deep into Svay Rieng Province, which embraced the Parrot’s Beak, linking up with other units that had been lifted in by helicopter. By May 16, a total of 90,000 American and ARVN troops were engaged in search and destroy operations in the dense forests. In support of the ground operations, the allied air forces flew more than 14,000 attack sorties against North Vietnamese and Khmer Rouge troops and supply depots. B-52s based in Guam flew 653 bombing sorties. A U.S.-Vietnamese naval task force swept up the Mekong River opening a supply line to Phnom Penh which was being harassed by the Khmer Rouge.

Militarily, the Cambodian incursion, mounted over seventy-five days before the invasion force retired to Vietnam, was deemed a success to the extent that it attained its immediate objectives. Most large enemy units retreated inland before the onslaught, suffering 11,349 of their combatants killed and 2,328 captured according to the MACV count. The U.S losses were 284 dead, 2,339 wounded, while ARVN casualties were put at 800 dead and 3,410 wounded. Some 600 weapons and other supply depots were taken. COSVN was said to have been forced to displace west of the Mekong, disrupting its command and control of units in South Vietnam.

But it was a short-lived success for Lon Nol, who had been given no advance warning of the invasion. When Henry Kissinger finally sent Alexander Haig, his military aide, to inform him of the overall strategic plan, Lon Nol, the ever emotional general, was reduced to tears and panic upon being told that American troops would be withdrawn in July after completing their sweep of eastern Cambodia. A promise of material aid and air cover was small comfort to Lon Nol, who knew then that his forces would be shortly confronted by the larger Communist units which had retreated inland to escape the bombings. In practical terms, while the American invasion might have secured the western flank of South Vietnam, Lon Nol was being abandoned except for air support, which was of limited value.

Politically, the Cambodian invasion was a disaster for the Nixon administration. There were moves in Congress, affronted by the covert operations, to cut off funding for the Cambodian operations. College campuses exploded with massive antiwar demonstrations. The most violent was at Kent State in Ohio, where Sihanouk had once spoken to a receptive student audience. Students there hurled rocks at National Guardsmen who were using tear gas to contain the campus antiwar rally. The Guardsmen retreated before the barrage to a nearby hill. In the confusion that followed, sixty-one shots were fired into the crowd of students. When the field was cleared, two boys and two girls lay dead on the campus; eight other students were wounded. A photo of Mary Ann Vecchio screaming as she crouched over the body of a student became an icon of the antiwar movement.

It soon became apparent that the ground invasion, although it imposed heavy losses on the North Vietnamese and Khmer Rouge, had failed to effectively root them out. By 1972, an estimated eight thousand Cambodians resentful of American intervention, particularly the bombings, had rallied to the Khmer Rouge, and four North Vietnamese divisions had extended their control from the border region to much of the country. When there was an intensification of attacks on the Lon Nol forces, Nixon ordered a massive resumption of B-52 carpet bombing, which struck deeper into Cambodia and continued until 1973. The final phase of the bombing, aimed at containing a Khmer Rouge advance on Phnom Penh, blasted the densely populated area around the capital. The village of Neak Luong was hit, and more than 125 Cambodians were killed. The bombing of the village was labeled a targeting mistake, and for this error, the air force imposed a fine of seven hundred dollars on the bombardier of the B-52. The bombing ended on August 15, 1973, when Congress cut off funding amid widespread denunciation of Nixon’s concealment of the extent of the bombing and some public calls for his impeachment.

A study conducted by Ben Kiernan and Taylor Owen in 2006 concluded that the United States from October 4, 1965, to August 15, 1973, dropped 2,756,941 tons of bombs in 230,516 sorties on 113,716 Cambodian sites. The tonnage compares with some 2 million tons of bombs dropped by the Allies during all of World War II. The Kiernan-Owen study was based on air force data released by President Bill Clinton when he visited Vietnam in 2000 which detailed the bombings of Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos from 1964 to 1975. Clinton made the data available to assist in the retrieval of buried un-exploded ordinance.

Estimates vary widely on the number of the civilian deaths resulting from the bombings. The Kiernan-Owen study cited the consensus estimate of 50,000 to 150,000 but projected the possibility of higher figures if other data were made available on the extent of the bombings.

In strategic terms, possibly the most deleterious effect of the bombing was the power that accrued to the Khmer Rouge as a consequence of the resentment it engendered among the Cambodian peasants. Many thousands of them rallied to the support of the Khmer Rouge. The population was also resentful of brutal repression under Lon Nol, particularly of the ethnic Vietnamese minority, which caused thousands of deaths. Another factor drawing support for the Khmer Rouge was the alignment of Sihanouk, a popular figure among the peasantry, with Pol Pot. At one point Sihanouk visited the Khmer Rouge in the field during their battle with Lon Nol’s forces.

The surge of popular support for the Khmer Rouge opened the way for their victory march on Phnom Penh. Lon Nol, suffering from one of his nervous breakdowns, fled the Cambodian capital on April 1, 1975, to exile in Hawaii, leaving Prince Matak to face the incoming Khmer Rouge, who promptly executed him. U.S. ambassador John Gunther Dean decamped with his staff on April 12 aboard marine helicopters to a navy ship standing by in the Gulf of Thailand. Most foreign correspondents also left the city. Wes Gallagher, the vice president of the AP, ordered all members of his bureau to leave what had been one of the most dangerous assignments during the Indochina wars. Thirty-four correspondents had been killed in Cambodia or were missing. Twenty-five were lost in 1970 alone. In the spring of that year, after Lon Nol ousted Prince Sihanouk in his March coup, a bevy of correspondents descended on Phnom Penh. Venturing out of the capital, many were ambushed, presumably by Vietcong, North Vietnamese, or Khmer Rouge units. Some of those who were captured were released, but others were executed. Between April 5 and April 16, ten journalists who headed out to Parrot’s Beak to cover the American invasion did not return. Among them were two Americans, Sean Flynn, the son of the movie actor Errol Flynn, working as a photographer for Time magazine, and Dana Stone, of CBS News. In the worst debacle, American and Japanese members of CBS and NBC television crews died in May when, disregarding a Cambodian Army warning, they drove from Phnom Penh down a highway into a Communist ambush. Those not killed immediately apparently were executed the following day.

Sydney Schanberg of the New York Times was among the few correspondents who stayed on for the Khmer Rouge occupation of the Cambodian capital. Prior to taking up his post as bureau chief in Phnom Penh, we had cautioned him in New York not to take undue risks. “No story is worth a man’s life,” he was told by James Greenfield, the foreign editor. Nevertheless, after some hesitation, on the eve of the evacuation of the American Embassy staff, Schanberg decided to remain in Phnom Penh. What happened to him and his Cambodian assistant, Dith Pran, would become an epic chronicle in the history of American journalism.

The Khmer Rouge entered Phnom Penh on April 17 and were welcomed by flag-waving citizens who evidently thought that Pol Pot would be a gentler master than Lon Nol. The Western press corps was no less sanguine. Typical of press reaction, four days before the Khmer Rouge took Phnom Penh, Sydney Schanberg reported: “It is difficult to imagine how their lives could be anything but better with the Americans gone.” The Times carried Schanberg’s dispatch under the headline “Indochina without Americans: For Most, a Better Life.” Schanberg added, however, in the same piece: “This is not to say that the Communist-backed government, which will replace the American clients, can be expected to be benevolent.”

On the first day of the Khmer Rouge occupation, Schanberg was given a better sense of what could be expected. Years later I asked him for an hour-by-hour account of what happened to him and Dith Pran, his Cambodian assistant and photographer, on that day. This is what he told me:

5 A.M.—As I started to file the final page of my story for the paper of April 17, the teletype connection to Hong Kong broke and could not be restored. So Pran and I left the telegraph office and started driving cautiously around the city to see what was happening. Through the night, bitter fighting had raged on the edges of the city, setting whole neighborhoods on fire. Several mortar rounds fell not far from the telegraph office.

5:30 A.M.—Khmer Rouge guerrilla troops in black-pajama dress are entering the capital from all sides, by land, river boat and bridge. Government soldiers are throwing off their uniforms and hurriedly putting on civies. We retreat to the Hotel Le Phnom, where most of the press always stayed. Only about a dozen foreign journalists have remained in the capital.

6 A.M.—We listen to the radio as we pack our belongings and canned goods for a likely move to the French Embassy, which has been agreed upon as a sanctuary for foreigners. The victors have taken over the Government radio station and are telling Cambodians to lay down their arms because Angka (“The Organization”) is their new Government. Leaving our suitcases where we can get them in a hurry, we go for a walk not far from the hotel to get a sense of whether there is major risk. We meet a few of the insurgents and converse with them through Pran without incident. But they are cold and distant. They tell us of the strict rules of behavior and suggest we should follow those rules. In the central part of the city, many Cambodians are hailing the Khmer Rouge conquerors showering them with flowers. Some people are hanging out of their windows shouting peace slogans. But there are harsher reports from other parts of town and rumors of a forced evacuation.

12 P.M.—Around noon, Pran, John Swain of the London Times, our Cambodian driver and I believing mistakenly it’s safe enough . . . we make a foray to the main civilian hospital, Preah Keth Mealea, to assess the casualty situation there. The place is a charnel house. Only a few nurses were brave enough to report for duty—no doctors. Supplies have run out and there are lots of dead bodies. Many of the wounded are bedded out on the stone floors and blood drips down the staircases. We take some pictures but it’s hard to look at it and we go down stairs, get in the car and head for the hospital’s main gate. Our car is blocked. A Khmer Rouge squad is coming through the gate driving a captured armored personnel carrier. Pran at once tells us to do whatever our captors ask. He had recognized instantly their lack of inhibition about blowing us away. I remember thinking desperately, but without saying it: “For God’s sake, Pran, stop arguing or they’ll kill you.” The Khmer Rouge push us into the armored vehicle through the hinged back door and Pran followed. I was able then to ask him what he was arguing about. He explained that the Khmer Rouge had told him and the driver to take off since they wanted only “the big people.” The driver went off but Pran kept insisting to the Khmer Rouge that he had to stay with us and they finally let him get into the armored vehicle with us. From inside the vehicle, Pran kept telling the Khmer Rouge we were Frenchmen who were there to tell the world about their victory, a refrain he repeated over and over for the next several hours. As we drove on, the Khmer Rouge stopped to pick up two captured men in civilian dress. Pran recognized both of them as officers in the small Cambodian Navy. One of them began to pray, putting the ivory Buddha he wore as a pendant in his mouth. The other officer handed me his wallet and asked me to hide it and thus hide his identity, assuming apparently that I as a foreigner had some magic. I took it and hid it under the sandbags on the floor. When we arrived at our destination—a Mekong River bank in the northern part of the city—the metal rear door was swung open and we were ordered out. Two soldiers stood on the bank, pointing their AK-47 rifles at us from their hips. I and I’m sure everyone in the vehicle thought we were going to be mowed down immediately and rolled into the river. But Pran leapt out of the vehicle and starting arguing for us again—and kept importuning the Khmer Rouge pretty much non-stop for the next three hours as we waited in the sun with our hands behind our heads, the guns pointing at us. And then, Pran quieted down. There was a command and the guns were lowered— and we were, in short, released. Some of our belongings were returned.

It was 3:30 P.M. As the three of us were leaving the riverbank I looked back and saw the two Cambodian officers sitting on the ground under guard, looking pale. One of them was still praying. To watch that was to see the dark bottom of helplessness.

4:30 P.M.—We got back to the hotel. A jeep was parked outside with two Khmer Rouge holding weapons topped by grenade launchers. An International Red Cross worker came out of the front door. He told us the Khmer Rouge had given an order that everyone had to be out of the hotel in 30 minutes. I asked him when exactly did they give that order. He said: “Twenty-five minutes ago.” We grabbed our suitcases and began walking up the boulevard toward the French Embassy. The street was filled with Cambodians being herded out of the city. Sandals fell off their feet as they fled littering the ground. The Embassy’s swinging gates were locked because throngs of Cambodians were trying to get in. We climbed over the seven-foot wall. The French told us Cambodians had to sleep outside, not in the Embassy building. I waited until dark and then brought Pran inside. A few days later, after our efforts to forge a British passport for Pran had failed, the Khmer Rouge ordered all Cambodians to leave the Embassy and join the agrarian revolution in the countryside. To avoid the crush, Pran and some friends left a day before the deadline and began walking up Highway Five. And his four-and-a-half years in hell began.

After thirteen days in the French Embassy compound, Schanberg and other foreigners were hauled in a Khmer Rouge truck convoy to the Thai border. On arrival in Bangkok, after recovering from the trauma of his experience, Schanberg went to the Times office and wrote a series of stories on what he had witnessed, which were published on May 19 on more than two pages of the Times.

With the occupation of Phnom Penh, Pol Pot, head of the Center, the leadership group of the Khmer Rouge, proclaimed the establishment of Democratic Kampuchea and took the title of premier. Immediately, he set about creating what he envisioned as a racially pure Khmer, classless, essentially agrarian society “cleansed of all foreign influence.” To consolidate his absolute power, Pol Pot ordered the evacuation of the cities, which he viewed as potential centers of opposition. Their inhabitants were force-marched into the countryside, where they were herded into prison camps or into labor gangs. Schools, hospitals, factories, and monasteries in the urban areas were shut down. Executions ensued immediately of Cambodians who had served as officers in Lon Nol’s army or as officials in his civilian administration. An estimated 20 percent of the population, about 1.57 million people, died in the holocaust at the hands of the Khmer Rouge in the years 1975 to January 1979 through execution, starvation, unattended illnesses, overwork, or other mistreatment. The Vietnamese and Chinese resident minorities were prime targets of Pol Pot’s execution squads. The holocaust ended when a Communist Vietnamese army battling through Cambodia seized Phnom Penh in January 1979. The Khmer Rouge had been scuffling with the Vietnamese for years over rival claims to the Mekong Delta. Pol Pot fled by helicopter to a retreat in the jungle of northern Cambodia, bordering on Thailand, where he died in a hut in 1998 and was cremated on a funeral pyre of discarded tires and other junk.

Prior to Pol Pot’s death, Sihanouk was witness to much of the carnage instigated by the dictator. Returning to Phnom Penh from Peking after the Khmer Rouge occupation of the Cambodian capital, he was installed by Pol Pot as a powerless head of state. But in the next year, on April 4, 1976, he was deposed, later denounced as a traitor to the revolution, and spent some time under house arrest. When the Vietnamese invaded Cambodia in December 1978, Pol Pot rehabilitated Sihanouk politically and dispatched him to New York to appeal to the United Nations for help. Sihanouk failed, and the Vietnamese occupied Cambodia for the next ten years. In 1993, Sihanouk was restored in Phnom Penh as king but later, in ill health, retired to self-imposed exile in Peking. He abdicated the throne in October 2004 in favor of his son, Norodom Sihamoni.

The Vietnamese seizure of Cambodia provided Dith Pran, who had saved Schanberg’s life, with the opportunity for escape. During the Pol Pot repression, posing as a simple peasant, he had suffered beatings and starvation. Visiting his hometown after the Vietnamese invasion, he found that more than fifty members of his family had been slaughtered. Covered with graves, its wells filled with bones and skulls, the village land had become known as the “killing fields.” Later, Pran was able to send a message to Schanberg through Eastern European journalists who were visiting the village where Pran was working under the Vietnamese as an administrative chief. In July 1979, Pran covertly made his way to the Thai border and crossed over to a refugee camp, where he contacted Schanberg through an American relief officer. Schanberg had been making ceaseless efforts to find Pran. When he was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in International Reporting in 1976 for “his coverage of the Communist takeover in Cambodia, carried out at great risk,” he accepted the prize on behalf of Dith Pran and himself. Within a week after learning that Pran had reached Thailand, Schanberg found him in the refugee camp and brought him to New York. In Schanberg’s book The Death and Life of Dith Pran, written in 1980, and in the 1984 film The Killing Fields, Dith Pran was lauded as a heroic, selfless holocaust survivor. From the time of his arrival in New York in 1980, where he worked as a photographer for the New York Times, until his death in a New Jersey hospital of pancreatic cancer on March 30, 2008, Dith Pran remained a passionate advocate and worker for human rights. In my many encounters with him at the Times, although he was treated as a hero, I found him to be the most modest of men.