The story of Moses is very personal to me, having followed me on hound’s feet since the days of my youth, resurfacing over and over again in various ways throughout my life.

When I was a mere lad of 11 years old, I wrote a report on the Pharaoh of the Exodus, roughly 200 words long. It was this little project that allowed me to meet the man who would inspire me on to archaeological and historical critical thinking, Dr. Charles Aling, who became the president of the seminary I attended a decade later, and, for the last 25 years, has been the chair of history at Northwestern College in St. Paul, Minnesota.

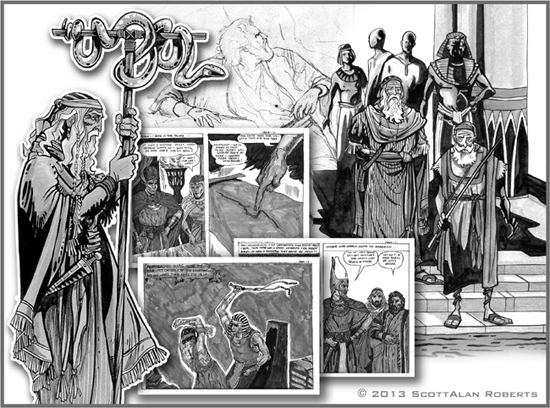

When I was 13 years old, I created an elaborate “Moses and the Exodus” comic book, rendered in colored markers, garnering me the attention of a Christian high school to which I was given a three-year scholarship as a result. The three little insets in the following image show that artwork from my early years, as well as other renderings of Moses for other publishing projects that spilled into my adult life.

In my seminary days, while pursuing my master’s, my interest in Moses and the Exodus continued when I wrote a paper on the patriarch and the educational system he would have encountered in 18th Dynasty Egypt.

A smattering of my “Moses” artwork projects starting from eighth grade to my adult years.

In that paper I also, for the first time, explored the various dating systems incorporated by academics who, throughout the years, have striven to identify and understand the historical context of the Great Exodus of the Bible. It was an exercise in an ongoing personal study for me that has been peripherally invasive throughout my entire life.

The Bible stories once held a significant place in my spiritual life, and I adhered to them by faith as being God-breathed, factual accounts, decisive cogs in the greater machinery of the religious history of my personal spiritual journey. But the gears of that old machine became worn and rusty, lacking the fine oil of fluidity and efficacy. And soon those threads seemed to stretch the boundaries of credulity as my life drifted further from the theologies and politics of my particular denominational religion.

And so I put them all—the Sunday school tales, religious legends, and liturgical mythologies—on the back burner of faith, and there they remained until I once again was driven to apply critical thinking to the stories that seemed too legendary and mythic to be the accounts of real people. I found an inextricable drawback to those things that I had spent years discrediting as actual events and real people. I wanted to know more about them. So I started studying.

And all of that has culminated in the books I have been writing for the last few years: The Rise and Fall of the Nephilim (an attempt to find sense in the varied religious mythologies), followed up by The Secret History of the Reptilians, which was my way to think through the Serpent and his religious/historical context. Both books bordered on the not-so-biblical as I used them to answer the call of intrigue into alternative theologies and history.

Although I have not come completely full circle, I have found that there is so much more to what I was taught in the hallowed halls of religious academia. I still struggle with letting go the bonds of what used to be a mandated blind faith, wanting to find substance—which, to me, is the only way one can reach beyond dogma and denominational theology to find the Source of fact and, yes, even Truth.

I needed—and still need—to find a truth that is not simply in the eye of the beholder or an empty exercise engaged for an hour on Sunday morning, but that envelops reason and critical thinking, standing on its own merits as opposed to someone standing at a pulpit or lectern telling me it is so.

My recent expedition to Egypt with John was a necessary thing for me. I needed to get my feet in the sand, so to speak, and wrap my head around the enormity of the history, and make a pilgrimage to the places where Moses was said to have trod. I walked the temple floors he walked, and climbed the same mountain he climbed—and in some sense, came away knowing something different than I did before. I saw things Moses saw, and, in some respect, heard his voice and felt some of his presence in ways that can’t be shared between the covers of this book.

I left Egypt a very changed man.

I am convinced that Moses existed, and I am convinced that he is identifiable in the Egyptian record. And that is what I am going to share with you now.

John has a completely different view when it comes to the facts presented in this book, and without putting words into his mouth, I would say that he has, as have I, walked away with a greater understanding of this perplexing, enigmatic character so buried in biblical legend.

And in so saying, I would add that not only has the research and writing of this book been an act of discovery, but it has also in a very elemental way given my faith the substance it had lost long ago.

—Scotty Roberts

April 30, 2013