Tip your head back, close your eyes, and breathe deep the air around you. It is filled with the aromas of your life and environment—sometimes the things we take in so subconsciously—such as the scent of our homes, the leather upholstery in our automobiles, the oven in the kitchen, the soapy smell of the clothes dryer exhaust, and the scent of hewn grass wafting in through open summertime windows blending with the sound of passing garbage trucks, sirens, and children playing in the backyard. Now, imagine your senses being transported to another time and another place, where the air is arid and dry and hot, with only the faintest hint of moisture filling your nostrils as the massive Nile waters roll slowly by, evaporating into the air around you. The scent of water, fish, and papyrus reeds bending in the mild breeze from their place in the marshy patches leading up to the river’s edge fill your nostrils with the sweet, pungent odor of green. In the distance, carrying on the ever-so-faintly incensed air blending into the warm dustiness are the low, melancholic, minor-keyed melodies of the priestly chants, mixed with the sound of the bustling city life echoing off the stone structures. Cheers and joyous shouting are raised into the mix as the Pharaoh rides his chariot along the processional way, throngs of people crowded along the route, in, around, and atop the sphinxes lining the avenue. The smell of kitchen fires, baking bread, and boiling stews of oxen mix with the smells of roasting geese, leeks, garlic, and onion. A cacophony of sensuality greets you. And when you open your eyes to that first, blinding white of the desert sun, the city is bathed in bright light, glistening above the sparkling waters of the river Nile….

Any good story relies not only on its characters, but also on the setting in which they are placed. Likewise, qualitative study on any topic from antiquity needs a good reference point; a stage on which to block the characters who move in and throughout the play. Establishing the life and deeds of such enigmatic figures as Moses, Aaron, and Miriam, and their more-than-probable connection to the royal houses of 18th Dynasty Egypt is possible only by taking an acute, intrinsic look at the stage whereon they acted out their destinies. It is our intention to establish not only the circumstantial evidence that links these biblical protagonists and antagonists to real history, but to remove their Sunday school pageant bathrobe and bedsheet costumes, raising them out of relegated storybook myth and legend to stand openly and unabashedly on the stage of human history within the walls of the temples and palaces of ancient Egypt.

So, before we can even begin exploring the various evidences, ideas, suggestions, and theories that we wish to present, we felt it appropriate to pull back the heavy velvet curtain, walk you to center stage, and begin taping off the players’ marks on the stage floor. As the backdrop unfurls behind you and the flats of history roll into place on stage left and right, use your imagination and let us transport you from whatever chair, sofa, bed, or bench you now find yourself on to the banks of the sun-sparkled waters of the River Nile and one of 18th Dynasty Egypt’s ancient capitals, Thebes, the bustling, magnificent river city of the pharaohs, where the Temple of Luxor was referred to in ancient times as Ipet-resyt, the “Southern Sanctuary.”

Located in middle Egypt, some 400 miles south of modern-day Cairo and 118 miles north of Aswan, sandwiched between the western and the eastern deserts with the Theban mountain range hovering over the western boundary, Thebes embraces the many secrets and epic legends that it has witnessed over the centuries.

The city of Luxor (ancient Thebes), as it appears today, rising around the ancient Temple of Luxor.

Although the city of Thebes was home to the Egyptian monarchy in the New Kingdom, it is difficult to understand how Moses interacted and traveled between the Pharaoh in Thebes and the Hebrews in Goshen, in the northern Nile Delta. According to Genesis 49:9–10, when Joseph, the son of Jacob, was made vizier in Egypt some 400 years prior to the events of the Great Exodus, he relocated his Canaanite family to the Land of Goshen, which has been placed in the delta region of the Nile, to the east of present-day Cairo, in the fertile, marshy expanse of the Wadi Tumilat. And there, throughout the next four centuries, the family of Jacob—about 70 people—grew into the vast number of Hebrews, eventually enslaved by the Pharaoh, who, according to Exodus 1:8, “had no regard for Joseph.”

The big question is: If the Pharaoh and his family primarily lived in Thebes, how could he interact with the representatives of the Hebrews who were living and working 400 miles to the north in Goshen? He could if there is some historical credence to the idea that the royal family moved back and forth between Thebes, the capital, and Memphis, the religious center. Its logistical proximity to Goshen would certainly open the door for two glaring points in the biblical story: 1) The mention that Moses’ birth mother, Jochabed, sent him down the Nile in a basket, eventually ending up in the pools of the royal palace, could not have happened at the palace in Thebes, if, theoretically, the Hebrews were living 400 miles north in Goshen. Distance notwithstanding, keep in mind that the Nile River flows north, toward the Mediterranean Sea, not south toward Thebes/Luxor. The city of Memphis, however, stood in the region just west of Goshen and north of present-day Cairo, and was filled with Nile River canals intersecting all over the place, so the Hebrews were just down the canal, and 2) 80 years later, when Moses and Aaron confronted the Pharaoh demanding the release of the Hebrew slaves, the monarch is said to have angered at their insolence and issued an edict that the Hebrews would have to go find their own straw for their brick-making. This would have been unlikely were he at the royal palace in Thebes while the Hebrews’ brick-making operation was in Goshen, 400 miles to the north. Without the convenience of video conferencing or Moses possessing an iPhone, the Pharaoh would need to be in some close proximity to the slaves’ base of operations. So, the plot thickens. Thebes or Memphis? We’ll examine this in much deeper detail later in these pages.

Thebes was a city of ancient splendor; a beautiful, artistic center that was the jewel of Egyptian royalty and spirituality, whose east bank was the celebration of light, life, and living mortals, while its west bank was an equal celebration of death, eternity, and the immortals. Nowhere does there seem to be a settlement of common slaves near this immaculate city. Thebes was set in a spiritually charged landscape, and the question of communication between Moses, Pharaoh, and the Hebrews is brought to bear by simple logistics on a map of ancient Egypt, and the absence of a major slave population’s expansive settlement in this cultural heart of the kingdom.

1 And afterward Moses and Aaron went in, and told Pharaoh, Thus saith the LORD GOD OF ISRAEL, LET MY PEOPLE GO, THAT THEY MAY HOLD A FEAST UNTO ME IN THE WILDERNESS. 2 And Pharaoh said, Who is the LORD, THAT I SHOULD OBEY HIS VOICE TO LET ISRAEL GO? I KNOW NOT THE LORD, NEITHER WILL I LET ISRAEL GO. 3 And they said, The God of the Hebrews hath met with us: let us go, we pray thee, three days’ journey into the desert, and sacrifice unto the LORD OUR GOD; LEST HE FALL UPON US WITH PESTILENCE, OR WITH THE SWORD. 4 And the king of Egypt said unto them, Wherefore do ye, Moses and Aaron, let the people from their works? get you unto your burdens. 5 And Pharaoh said, Behold, the people of the land now are many, and ye make them rest from their burdens. 6 And Pharaoh commanded the same day the taskmasters of the people, and their officers, saying, 7 Ye shall no more give the people straw to make brick, as heretofore: let them go and gather straw for themselves. 8 And the tale of the bricks, which they did make heretofore, ye shall lay upon them; ye shall not diminish ought thereof: for they be idle; therefore they cry, saying, Let us go and sacrifice to our God. 9 Let there more work be laid upon the men, that they may labour therein; and let them not regard vain words. 10 And the taskmasters of the people went out, and their officers, and they spake to the people, saying, Thus saith Pharaoh, I will not give you straw. 11 Go ye, get you straw where ye can find it: yet not ought of your work shall be diminished. 12 So the people were scattered abroad throughout all the land of Egypt to gather stubble instead of straw.

—Exodus 5:1–12 (Authors’ emphasis)

Was it from the palace at Thebes that Pharaoh Thutmoses I, Amenhotep II, or even Amenhotep III issued angry edicts for the Hebrew babies to be killed or their tally of bricks to be increased and their labors to be harshened by the gathering of their own straw? Or was there a connection to the northern city of Memphis, which lay in close proximity to Goshen? The necessity of these questions weighs heavily on the substance of a latter part of this book, where we examine the physical logistics of a biblically recorded mass migrational exodus of what would had to have been, by the biblical accounting, nearly one-and-a-half million slaves. Overnight.

Perhaps Thebes, being the political, cultural, and spiritual capital of Egypt gave accommodation, diplomatic immunity, and possibly even some sort of governmental housing to the new faces of the Hebrew slave population, Moses and Aaron, as well as the Hebrew “taskmasters” and “officers,” but at this point in these pages, there is a need to engage in less speculation and more digging into the historical efficacy of both places.

Today, the city of Thebes goes by the name of Luxor or Louksour, as the French named it during their occupation, separated by the River Nile as it winds its way northward toward the Mediterranean. The east bank is home to the main city with hotels, restaurants, and other touristic trappings, what one would expect of such a historic center that has catered to numerous visitors throughout the past 2,000 years, but more importantly it is home to Karnak (Ipet-isut), known as the world’s largest open-air museum. Hidden behind its crumbling walls, there are ancient secrets and ceremonial practices that glorified the divine Theban triad only known to the High Priests that walked its glorious halls and who bathed in the coolness of the sacred lake that lies within its heart. It is connected by a Sphinx-lined avenue that was once trodden by the feet of the pharaohs of ancient Egypt. Today, this processional route lies in a sad state of ruin, but still manages to inspire and awaken those emotions of grandeur and pompous ceremony that it once enjoyed. The avenue terminates at the Temple of Luxor (Ipet-resyt), a truly magnificent structure built by various pharaohs that eventually succumbed to the Roman occupation. It once housed a beautiful basilica, which now holds the Mosque of Abu Haggag, allowing this sacred location to continue as a place of worship and pilgrimage.

The Gate of Luxor Temple as it appears today.

Both of the temples would have figured heavily into the Exodus story line yet are remiss from the biblical narrative. It is not inconceivable to suggest or imagine that in the formative years of Moses’ youth he would have walked upon the very stone slabs that so many tourists tread today. The view would not have been that dis-similar within the confines of the pillared halls with the constant sound of wooden hammers against metal while water boys dealt refreshing Nile water to the stone masons as they carefully and gently carved the scenes of the Opet Festival. But at the same time Moses would have enjoyed the company of its incumbent priests with their freshly shaven heads and their flowing white robes, listening intently to their words of wisdom and knowledge as they recited the sacred stories of the Gods to him, and in doing so, preparing Moses for his royal duties that one day he would have to perform.

The West Bank is home to the ancient Theban Necropolis, Land of the Dead, where they rest peacefully within their tombs, emblazoned with sacred texts from the Book of the Dead, while their ka travel freely among the living, visiting their earthly homes and loved ones they left behind, eating and drinking as if life was an eternal pleasure. It is here we find the infamous Valley of the Kings and the sprawling stone mortuary temples of various pharaohs that line the western desert’s edge, now preserved piles of stone, resembling a mere fraction of their original grandeur. The lonely doorways now provide access to empty spaces, but once were beautifully decorated chambers adorned by hand-crafted furniture and colorful fabrics. If one could pause for a moment, it is easy to imagine the sweet smell of burning incense as it passed from chamber to chamber, filling the voids with the aromatic odors of the east, their gentle smoke being highlighted by the shards of penetrating light that break through the small carved windows.

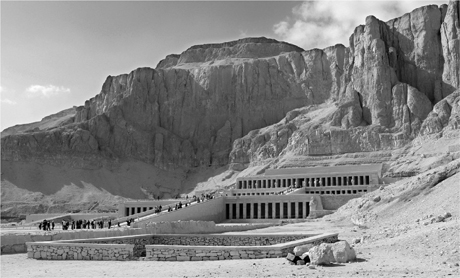

One such temple is the magnificent mortuary temple of Djeser Djeseru in Deir el Bahri, built by Hatshepsut under the hand of appointed chief architect Senenmut. The never-ending cycle of temple life included delivery after delivery making its way through huge sycamore doors with heavy bronze hinges, encrusted with green oxidization. Massive lion-headed bolts were drawn back to allow in the stream of men and their donkey-driven carts carrying the necessary supplies of grain, fruits, and precious oils. Behind them were the livestock, many of which would be required for the daily offerings within the ceremonial rites and rituals that were performed for the deities and the deceased owner of the temple complex.

Hatshepsut’s temple of Djeser Djeseru, built by her Grand Vizier and Royal Architect, Senenmut.

The cottage industry that produced all that was required for the easy running of the temple was constantly busy. The kitchens were always preparing and serving meals to those who had spent the morning laboring in the fields or to the priests who had just finished their first set of daily rituals. But these were nowhere near as tremendous as the feast that was being laid out before the visiting god on his offering table, later to be shared among the temple staff and their families once the deity had satisfied its hunger.

The weavers and their apprentices spun yard after yard of fine cloth and linen in preparation of the ongoing mummification process that took place regularly; the embalming workshops requirement for their supply of sacred linen never abated. It’s not a huge leap to place Moses, Aaron, and Miriam into such a scene.

It is worth mentioning that the name of these temples translates as “House of Millions of Years”; it was the belief of their architects that the dead Pharaoh would travel back and forth from the Underworld to visit his earthly house—hence the name.

As we previously mentioned within the Introduction, ancient Egypt is as familiar as the dark side of the moon, and rightly so in many aspects. Archaeologically speaking there is an immense wealth of material pertaining to ancient Egypt and its people. Universities, libraries, and museums across the world have amassed huge collections of Egyptian artifacts that span thousands of years, not to mention the Grand Egyptian Museum. In pop-culture terms, other than the famous tomb of Tutankhamun, the Sphinx, and the Pyramids, not much is really well-known or talked about. The silver screen has portrayed ancient Egypt in many guises, from the mid-20th-century old black and white films of Boris Karloff as The Mummy to the action-packed adventures of Indiana Jones and his conquests across the world of antiquity. And let’s not forget the recent adventures of The Mummy trilogy, in which we see significantly important ancient names such as “Imhotep” come to life in front of us, performing rites and ceremonies that quite possibly bear some resemblance to the ancient events.

Ever since the first early European travelers began to navigate the Nile, tales of Egypt’s rich history began to filter their way back to mainland Europe, conjuring images related to the age-old stories such as Arabian Nights, Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, and of course the biblical narrative. Napoleon’s somewhat forced occupation of Egypt during the later parts of the 18th century led to the great scientific exploration of ancient Egypt’s history. His team of scholars, draughtsman, and engineers scoured the Egyptian countryside, recording and documenting all that lay in their paths. We have so much to thank Napoleon and his scientific team for; if they had not been so disciplined in their work, we would not know as much as we do today. It was his team’s discovery of the famous Rosetta Stone that eventually led to the decipherment of the ancient and lost hieroglyphic language by Jean-Francois Champollion in 1822, showing the academic world that the ancient text was a mixture of phonetic and ideographic signs.

As Egypt’s population grew, so did its cultivation of land and the subsequent reclamation of its ancient sites to make way for the necessary housing and industry that was growing within her. Many of Egypt’s glorious sites were being lost to the internal growth that flourished with its fame on the international stage. Egypt had always played a strategic part in colonial military maneuvers, but once more it was her history that brought with it European wealth and a necessity to renew its aging and somewhat-dilapidated cities.

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries the great discoveries began to make headline news around the world, and treasures beyond the imagination began to appear: golden chariots, death masks made from encrusted jewels and precious metals, everyday household objects that were familiar to the crowds, entire chambers full of immeasurable wealth that far outweighed anything Europe’s aging monarchies had to offer or could match in such splendor and opulence. It was during this time that Egyptomania gripped the public’s imagination, but behind the scenes, there was also a flurry of activity among the eminent archaeologists and Egyptologists as they raced to uncover artifacts and evidence that substantiated the biblical stories, searching for those all-important clues in the dusty ancient tombs as Egypt’s glorious past was being sold at a rapid rate to the highest bidder.

Huge caches of artifacts in wooden crates were being loaded upon steam-driven ships at Port Said and Alexandria to be transported back to Europe and beyond by unscrupulous middle men who acted as agents for the universities and aristocratic houses, all gripped by the Egyptomania bug, hoping to find a lost treasure hidden in the sands of Egypt or find a clue as to the whereabouts of the stolen Ark of the Covenant by Pharaoh Sheshonq.

Many a myth and legend were being analyzed to find the scantiest truth and locate those clues in the temples and tombs of the ancients, hopefully hidden within the colored reliefs and hieroglyphic writings. It was a time when Egypt was truly plundered by the Europeans. Of course Luxor was by no means an exception; it was here that many a young aristocratic man or woman came to take part in the illegal excavations, hoping to find an artifact that would secure his or her financial freedom. The West bank was a flurry of activity. No matter where you looked, there was an excavation of one kind or another taking place with the solemn tunes of the workers singing as they dug, removing centuries of sand and debris that had accumulated.

So, what was ancient Thebes like for Moses when he lived there during his first 40 years as the adopted son of a royal princess? He was an Egyptian prince in all but name. Did he have all the freedoms and associated attributes that were customary to a royal prince of that time?

As the authors have two opposing theories, the landscape of the Theban necropolis looks different to both of us. John’s theory is attached to the prolific building of megalithic structures that took place during the reign of Pharaoh Amenhotep III, which changed the entire landscape forever. Scotty’s theory belongs to that of a time when Pharaoh Hatshepsut walked among the living gods. Her grand temple clung to the Theban Mountain, its terraces adorned with huge statues proclaiming her rightful status as Pharaoh, remembering that she was indeed a female and not a male heir. However, these two periods of Egyptian history separated by less than a mere hundred years were considerably different in their settings. Military conquests, internal conflicts, and expeditions that flooded the land of Egypt with exotic goods, some of which had never been seen before, were all playing their parts in the development of these two opposing periods. The sheer wealth of Egypt was beginning to show through its Pharaohs’ ambitious building programs, all of which were dedicated to glorifying and praising the gods for their protection and blessing that they had bestowed upon the people of Egypt.

If we amalgamate the two opposing eras within the Egyptian history and present that collective map to you, it should makes things a lot easier. No matter what era in which we place Moses, be that the time of Pharaoh Ramesses II (which the authors agree is nearly two centuries too late on the time line) or Amenhotep III, he still would have stood in the halls of Karnak, or at the foot of the terraced Temple of Hatshepsut, as well as her small temple dedicated to Amun at Medinat Habu. And he most certainly would have known of the kings’ burials in the Valley of the Kings. It is plausible that he once stood on the Giza plateau and gazed at the wonder of his adopted ancestors’ building achievements, the great pyramids, and placed an offering at the paws of the Great Sphinx. It was at Saqqara that his possible adopted uncle, Crown Prince Thutmoses, participated in the sacred Apis Bull ritual with Pharaoh Amenhotep III. It would be wonderful to think that Moses once stood shoulder to shoulder with his uncle at that ceremony and possibly participated as a royal family member with all its rights, then destroying a similar effigy of the deity upon the fires at the foot of the Holy Mountain approximately 40 years later.

During that period there were no luxuries such as concrete and steel bridges that afforded one a safe crossing of the River Nile, nor had the motor boat been introduced with its petrol-driven outboards. One would have to pay the ferryman his due or live and work on one side of the river, only crossing when truly necessary, taking great care as not to wander too close to the Nile’s edge, for lurking just beneath its murky waters, the Nile crocodile patiently waited for its next victim. It was not until the opening of the Aswan Dam in 1971 that the crocodiles eventually vanished from the Egyptian Nile riverbanks. Ceremonial practices took place along the Nile’s edge to appease the Nile crocodile personified as the great God Sobek, the crocodile-headed deity that many a temple has been erected for in Egypt. It was considered a great honor to die in the crushing jaws of Sobek. However, it was probably not that honorable for the victim. During this period of history, the Nile was pivotal to the very existence of Thebes, its life-giving waters feeding the canals, which in turn irrigated the vast agricultural land that stretched along the flat lands. When the Nile flooded, it deposited its mineral-rich black sediment, giving Egypt one of its nicknames: the black lands. It was the ancient Greek historian Herodotus who stated that Egypt is the gift of the Nile, a sentiment that could not be closer to the truth.

Standing on the east banks of the River Nile during the New Kingdom (14th–19th Dynasties, 1550–1069 BC), looking toward the west bank, one would be greeted by a secondary island directly in front of where one is standing. This island gave its name to the village in which John lives today, Gezeirat, meaning “islands” in Arabic. Beyond this island, one would have been confronted by a series of complex canals fed directly by the Nile, denoted by their flag poles and landing stations, so they could still be navigated and used during the Nile inundation while the surrounding agricultural fields were covered by the rising flood waters of the Akhet season. These canals lead in straight lines to the various temples and shrines that dwelled on the west bank. The canals were not only transportation routes but also fed the agricultural fields during the low season, filling the temple granaries each consecutive year with the harvest known as the Shemu season. Everything was monitored and measured precisely, and the Nileometers would provide the temple priests with the correct height of the Nile, allowing them to calculate how much land had been irrigated and thus how much land and crop would be subsequently harvested. This was all necessary in order to avoid a famine. The slightest mishap or miscalculation would bring chaos, which was personified as the God Seth. Everyone who was not of the higher class or royal household was either employed in the fields, temples, quarries, or any one of the many associated infrastructures that went into the continuity of life, and all were working for the common good of the populace, in a divine collective worship for the living God, the Pharaoh.

In terms of our interests, the important palace pertaining to our discussions was located at the end of the southern canal system, the palace of Pharaoh Amenhotep III, commonly known as the House of Rejoicing, home to not only one of the Pharaoh’s private harems, but also the official living quarters of the royal family. In the 10th regal year of Pharaoh Amenhotep’s reign he arranged a diplomatic marriage with Gilukhepa, the daughter of Shutturna II of Mitanni. Historical records have shown that she arrived in Thebes with the entire splendor acquainted with a pharaoh’s wife, but also with 317 attendants in tow. Today, however, very little remains. Low-lying mud brick walls protrude out of the desert floor, a stark reminder of what was once probably one of the most splendid palaces in Egypt and home to some of ancient Egypt’s most glorious historical figures: Pharaoh Akhenaten, Pharaoh Amenhotep III, Queen Tiye (daughter of the great noble Yuya and his ennobled wife Queen Tuya), and the Crown Prince Thutmoses, not to mention all the other countless siblings and servants from Pharaoh’s extensive harem.

The Temple of Thutmoses III standing before the Tombs of the Nobles and the Theban Mountains.

The palace was extreme in every way for its day; excavations began in 1888 with initial minor exploration of the site carried out by Georges Daressy. Later, it was carefully excavated by the British Egyptologists Percy E. Newberry and Robb de Peyster Tytus, and again in the 1970s by Barry Kemp and David O’Connor. In the 1980s, a Japanese team uncovered dramatic ceilings that were painted with bright colorful scenes of wildfowl and nature; the floors and doors were ornately decorated as well. The steps were covered with images of bound enemies of Egypt, commonly known then as the “nine bows,” so that as Pharaoh walked upon them, he was symbolically crushing them beneath his feet. Sprawling across the desert’s edge, the palace was immense, with chamber after chamber and associated stores and servants’ quarters. It was bounded to its eastern edge by the great lake of Birket Habu (Lake Malkata). The whole area would have been electric. No matter where you gazed, there would be something to see: the royal princesses and their female courtiers, playing and frolicking by the water’s edge of the great lake while mocking the ever-watchful army officers; the chariots of Pharaoh’s private guard racing along the canal’s edge, checking on the sentries; the Pharaoh accompanied by his royal entourage as he harpooned Nile perch while his male courtiers jostled for that small gesture of appreciation from their living God; the queen and her royal fan-bearers fanning her gently as she reclined majestically upon the Gleaming Aten; and the Royal Princes, as they raced their horses around the tracks of the desert floor.

It would have been during this triumphant and splendid period that Moses could have witnessed the building of the House of Millions of Years for Pharaoh Amenhotep III, his adopted grandfather, built and designed for him by the great architect Amenhotep, son of Hapu.

Now, if we were to stand on the roof of the House of Rejoicing, we would be able to enjoy one of the most spectacular views that ancient history could ever afford us. Looking directly eastward we would be able to make out the great Temples of Karnak and Luxor on the east bank with their associated canals and sphinx-lined avenues. Turning toward the north, we would view the small shrine to Queen Hatshepsut and Crown Prince Thutmoses, lying within the grounds of the mound of creation where the Ogdoad first appeared and created man from clay and fornicated with them to produce the children of gods. To the northeast we can clearly make out the tremendous Temple of Pharaoh Amenhotep III with the colossi statues standing guard over its entrance and its walls towering toward the heavens, permitting only the rays of Ra to enter its colonnaded halls.

Then a little further to the northwest we can make out the stepped temple of Queen Hatshepsut as it climbs the sides of the Theban Mountain, with its ornate pillared terraces and its central polished limestone stairway, ascending to its inner Holiest of Holies. To our left, there is the Theban mountain range as it rises out of the desert floor, sporadically intersected by small apertures, which would provide access to the private tombs of the nobles, the viziers of past pharaohs, and the higher classes of the Egyptian elite, retelling the glorious stories of their owners on the walls in colorful relief and painted scenes of everyday life. Nestled to the southwest and hidden behind the escarpment, the Valley of the Queens, where the royal burials of the harems are located, is a much smaller affair than that of the Valley of the Kings. No matter where we look, we see structure soaring toward the heavens, some colorful and some not, some shining so brightly in the outstretched arms of the sun God Ra that it is difficult to gaze upon them.

If we turn further to our left and toward the south, we can see the Theban mountain range as it continues southward like a chain of mountain ridges with the open desert at its feet, making out the odd band of caravan travelers as they meander along the trade routes that connect Thebes with the southern nome of modern day Armant, where hopefully they can sell their wares.

To the southeast, at the far end of Lake Malkata’s embankments, the ramped station stands next to the lake’s great feeding canal. This station with its steep ramp and miniature obelisks was built to receive Pharaoh Amenhotep III during his Sed festival, a jubilee to celebrate his first 30 years as the living God over Egypt.

Now that you have a better understanding of the layout of ancient Thebes, it should not be too difficult to imagine Moses as the royal prince riding his chariot pulled by majestic horses alongside the canal from the banks of the River Nile to his adopted grandparents’ palace, racing Thutmoses along the way, passing the fields of farmers, and hurtling past the ceremonial procession of priests making their way to one of the Houses of Millions of Years, carrying with them to the tabernacle the visiting god in his or her barque shrine, a small golden box with its ornately carved scenes and sacred texts, Nephthys and Isis at either end, their wings outstretched in a protective manner, while the shimmering box lay atop a small golden replica boat suspended by golden poles that rest upon the priests’ shoulders bearing down the considerable amount of gold leaf that had been applied to all its surfaces.

A Barque Shrine carried on the shoulders of priests, from the walls of the Ramesseum, Luxor, Egypt.

Thebes would have been a tremendous sight, seeing the never-ending activity both on the east and west banks, fueled by the never-ending merchant ships that navigated the River Nile or the desert caravans that entered Thebes from both the eastern and western deserts via the heavily trodden trade routes.

These trade routes and the Nile River were the lifeblood of Thebes, and without them Thebes would be no more than a small farming community, part of a larger principality that made up the kingdom of Egypt. It was these very routes that the quarried stone blocks would have been transported along, hundreds if not thousands of workers pulling a hand-woven rope of twine, all working as one cohesive unit to maneuver the blocks along these tracks. The mighty wooden sledges would be carrying the megalithic blocks of basalt, granite, limestone, sandstone, and other quarried stones that made up the funerary equipment and architectural details of the temples.

Seeing one of these stone caravans emerge out of the eastern desert from the quarries of Wadi Hammamat would have been a sight that one can hardly imagine. The oxen in rows of 10 deep, harnessed to huge ropes and tackle, and behind them row after row of men, with their backs bent as they pulled heavy upon the ropes that lay across them like a spider’s web, while men and women carrying pots of grease and oil would splash the path ahead and under the wooden sledge as it slowly moved along the cleaned stoney ground, bearing the immense weight of the stone on its wooden raft. The dust rising from such a train would be seen for miles and the sounds could be heard across the desert floor to the outskirts of the Theban capital. Families began to line the streets to get a glimpse of their loved ones, throwing palm leaves and lotus petals at their feet, praying to the gods for the safe arrival.

The eastern trade route would have been the choice for the Exodus, providing them with a clearly marked route that eventually would have brought them to the shores of the Red Sea, or they could have branched off and taken the northern route that hugged the eastern mountain range and eventually ended up emerging by the mouth of the Suez Canal. Either way, they would have ended their journey on the main land at the same spot. (This is worth remembering for future discussion within the later chapters.)

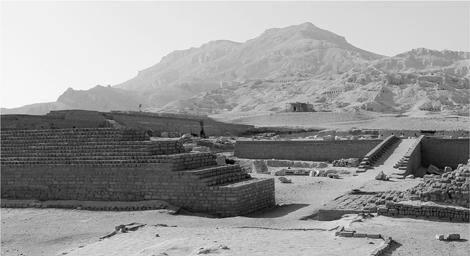

One of the main archaeological problems that today’s scholars face is the lack of archaeological material that pertains to the existence or location of the Theban acropolis, its town, its villages, and its suburbs. After years of excavations and clearing of accumulated debris, there is still no evidence to suggest sprawling cities, except for the worker’s village in Deir el Medina, which lies at the foot of the Theban Mountains. Many archaeological investigations have been carried out here throughout the years, with mountains of material recorded and documented, but alas it does not shed light on the whereabouts of the main Theban city itself. The same can be said of the small settlements that have been located on the northeastern side of Karnak Temple on the east bank.

The reason we bring this up now is to add this question mark to the Theban map that we have tried to emulate for you. The missing component raises important questions when dealing with the Exodus and alternative suggestions that we will explore later. But for now, it should be noted that, even though we have all this splendid architecture and grand landscapes, the actual towns and streets could have been located either on the west bank or the east bank, nestling between the various temple complexes. This has always been the suggested answer, and through the subsequent centuries these dwellings have merely succumbed to their natural fate of destruction caused by environmental erosion, and their remains reclaimed and reused in other building projects as time moved on.

The Theban necropolis was not inhabited by a mass population, but was, rather, a royal and ceremonial center with its associated workers and priests. The annual flood waters that rose with the inundation of the Nile must be taken into consideration when discussing the habitation of the common people; the low-lying lands that surround the temple complexes were indeed flooded during these high seasons. When Vivant Denon wrote his journal while accompanying the French scientific exploration team during the later part of the 18th century, he commented on the lay of the land, which he looked upon when he first arrived at Luxor. His maps clearly show a series of raised hills on two of which the temples of Luxor and Karnak were built. The west bank rises slowly toward the Theban Mountains, thereby protecting the temples and shrines that hug the western desert’s edge. Could it be inconceivable to suggest that the same practice was employed for the smaller and common dwellings, building them upon artificial platforms of debris and accumulated silt and other organic material? Later during the mid-19th century, an English artist by the name of David Roberts painted a picture of the colossi of Memnon, which were surrounded by water at the time. This would suggest that the protective levies that retained the rising waters behind them had indeed been eroded, allowing the swollen river to gain further access across the low-lying lands. Could this erosion be the reason why we do not see any evidence of common habitation today? It is merely a theory but plausible at the same time.

Another theory or suggestion is that the commoners were possibly nomadic in their living styles, migrating back and forth as the river rose and sank with its annual seasons. This would provide us with the necessary answers as to why there are no remains today, but again, we do not have any evidence to support this theory. When we gaze upon the relief scenes that adorn the temples and tombs throughout Egypt, we do not see tents or nomadic dwellers; what we see are small pillared courtyards with a surrounding structure that housed not only the owners but their servants and stores as well. The courtyard almost always had a central water feature with a small garden and a plantation of trees at the entrance outside. There are various examples of this design not only in relief, but also in scale models that were buried with their owners in the tombs of the nobles in Thebes, therefore suggesting that this type of housing actually existed not only in the afterlife, but quite possibly during their lifetimes. But where? In an unpublished account, John describes some of his findings as he explored the limestone quarries:

The Colossi of Memnon by David Roberts, 1848.

In the ancient limestone quarries of Pharaoh Hatshepsut that lie to the north of the Valley of the Kings, there is plentiful evidence to suggest that they were inhabited after they became sources of usable limestone as building material. Their ceilings still bear the red painted lines with pictorial markings measuring the widths of the strata in readiness for extraction. On the walls in some of the galleries that are quarried caverns, we have observed early Christian graffiti in the form of white painted crosses, but again no Hebrew symbolism. In one of these galleries, I have recorded and documented the use of fired brick and mud brick used together to form inner walls that would or could have been used as a basic form of habitation. It is worth mentioning that these quarries lie on the main trade route out of Thebes on the west bank leading to the Farshout and Asyut regions of Egypt. From an historical point of view, these areas were close to the temple complexes of Abydos and Dendera. There is no evidence to suggest that these quarries were used as places of refuge or habitation during the Pharaonic period, but during the Graeco-Roman period instead. However, they do provide us with a great example of how existing sites were reused for shelter and security.

Over the many years that I have researched ancient symbolism in Egypt, I have been fortunate to explore most of the Theban area and this includes the mountainous terrain and the trade routes and valleys that dwell within the Theban Mountains that contain a wealth of archaeological material, including inscriptions of dedications, adorations, mere name graffiti, and pictorial drawings; however I have yet to come across any symbols or associated inscriptions that pertain to a Hebrew connotation/relation. With all the various temples and shrines, canals, the great lake, and not to mention the thousands of tombs, the workforce that would have been needed to facilitate all these grand building programmes over the centuries would have been immense. But alas we do not have the common graves of workers of the time, we do not have their individual dwellings outside of the workers village; they just do not exist. Well not yet, anyway. Maybe yet to be discovered buried beneath meters of sand and debris, like Luxor temple was before the sands of time were removed.

Luxor Temple, before it was excavated, was buried almost up to the height of the inner courtyards. If one looks carefully today, one can still make out the post holes on the exterior and interior walls that once held the floor and ceiling timbers of the Christians and later Muslims that built their houses abutting the grand temple walls. The mosque that we mentioned earlier is located above the temple itself, sitting upon the pillars that stand in the first courtyard. With a doorway that now leads to nowhere, as the debris has now been removed one can freely walk through the inner courtyard at its original ground level.

What if the houses and mass burials of the common folk lie undisturbed beneath the modern city of Luxor today? It’s a maybe, a possibility. However, during the years of construction, no other remains have been discovered as yet.

Most of Egypt has a plethora of ancient sites that provide us with a wealth of material that deals primarily with the religious aspects of its society and the royal households, but no Pharaonic villages or cities have yet been discovered. There are plenty of examples, however, of Graeco-Roman architecture, so this does beg the questions: Where did they live? Where did the Hebrews, the so-called slaves of Egypt, live? When all is said and done, it is worth asking, when thinking about the great Exodus: Where did they all come from? This leads to the next question: Where did they all live? And where did the Hebrews spend their days in bondage? Was it in Goshen, or were they spread throughout the entire land of Egypt?

But before we dig in, let’s take a look at the continuing, sometimes-not-so-friendly dialogue between faith and academia….