THE SENENMUT THREAD

The Hebrews had grown far too numerous. Over the last generation, the lush, fertile Nile Delta had become their permanent home. They had emigrated there seeking refuge from the bitter famine that overtook the Canaanite region, and now these “Asiatics” were here to stay. They were beginning to overpopulate the land that had been given to them by the vizier, Zaphnath Panaaeah, known to their people as Joseph, the younger son of their patriarch, Jacob, known as Israel.

The eastern Nile Delta, where the Hebrews abandoned their nomadic ways, sinking their foreign feet into the most beautiful, lush part of the region known as Goshen, held some of the richest soil in all of Egypt. The pharaoh who had elevated Joseph to power as his vizier is the same pharaoh who had also given this land to the Hebrews. But he was not an Egyptian pharaoh at all. It is more than likely that he was one of the “Shepherd Kings,”1 the heqa khaseshet— the Semitic race of Hyksos peoples2 from Syria and Canaan who had migrated to and infiltrated Egypt in a similar fashion as did the Hebrews. Hyksos is the Greek translation of the Egyptian phrase heqa khaseshet, but there is newer etymology of the word Hyksos (from the Egyptian hekw shasu), meaning “Bedouin-like Shepherd Kings” rendered, simply, “rulers of/from foreign lands.”3

Palm forest in the Nile Delta near Memphis.

Archaeologist Jacquetta Hawkes states of the Hyksos, “It is no longer thought that the Hyksos rulers...represent the invasion of a conquering horde of Asiatics...they were wandering groups of Semites who had long come to Egypt for trade and other peaceful purposes.”4 Their usurpation of the throne of Egypt was a gradual affair as they worked their way into Egyptian politics and governmental affairs over generations. From migrating shepherds to Egyptian kings, the foreign nomadic Bedouins became rulers of the Nile Delta and all of Lower Egypt, while Egyptian pharaohs ruled from Thebes in the south of Upper Egypt.

Eventually the Hyksos went even further than simple migration, and by the 15th Dynasty of the Middle Kingdom (around 1700–1650 BC), they had wrested the ruling power of northern (Lower) Egypt from the Egyptians, and established and held that pharaonic throne until they were ousted at the beginning of the New Kingdom (around 1600–1550 BC) by Ahmose I, who had already been on the Theban throne in the south of (Upper) Egypt for some time before. Ahmose invaded to the north and drove Khamudi, the last of the Hyksos rulers, out of Mennefer and the entire Nile Delta region.

The Nile River flows south to north with tributaries north of current-day Cairo spreading into the Delta “fan” before emptying into the Mediterranean Sea. The terms “Upper” and “Lower” Egypt might seem backward, as Lower Egypt is in the north Delta region, and Upper Egypt is in the southern regions. This is dictated by the northerly flow of the Nile.

According to the biblical account of the Hebrew migration to Egypt under Joseph and the Hyksos pharaoh in Mennefer (Memphis), the Egyptians were none too fond of foreign, shepherding peoples, and Joseph expressly told his brothers to mention to the pharaoh that they were shepherds. This directly supports the fact that the sitting pharaoh at the time of Joseph is none other than a Hyksos ruler, one of the Shepherd Kings, the rulers of/from foreign lands.

The biblical passage of Genesis 46:31–34 gives clues to the nature of the pharaoh and the ruling class in Egypt at the time of the Joseph story, lending plausibility to the notion that the entire account of Joseph’s time in Egypt and the migration of his father’s clan from Canaan took place while a Hyksos ruler sat on the throne of Egypt, placing it sometime during the 15th Dynasty. And it makes perfect, indirect, albeit plausible sense. The pharaoh who favored the shepherding people from Canaan, while the rest of the Egyptians detested them, is the one who grants the family of Jacob/Israel the “finest land in all of Egypt.” After all, they are “his” people.

31 Then Joseph said to his brothers and to his father’s household, “I will go up and speak to Pharaoh and will say to him, ‘My brothers and my father’s household, who were living in the land of Canaan, have come to me. 32 The men are shepherds; they tend livestock, and they have brought along their flocks and herds and everything they own.’ 33 When Pharaoh calls you in and asks, ‘What is your occupation?’ 34 you should answer, ‘Your servants have tended livestock from our boyhood on, just as our fathers did.’ Then you will be allowed to settle in the region of Goshen, for all shepherds are detestable to the Egyptians.” (Authors’ emphasis)

It is no wonder that the new pharaoh mentioned in Exodus 1:8, Ahmose I (1550–1525 BC), had no regard for Joseph or the Hebrews, as they were sharp reminders of the foreign rule of the despised Shepherd Kings. It is also no wonder that he wanted to cull their population and control their influence by placing them under harsh administration and the imposition of enforced labor. He didn’t want another “shepherding people” to have any possible foothold in the building of a new government or the usurpation of the Egyptian throne. This wasn’t an act of cruelty, it was an act of pharaonic responsibility from the Egyptian perspective. He kept his friends close, and his enemies even closer and more controlled.

8 Then a new king, to whom Joseph meant nothing, came to power in Egypt. 9 “Look,” he said to his people, “the Israelites have become far too numerous for us. 10 Come, we must deal shrewdly with them or they will become even more numerous and, if war breaks out, will join our enemies, fight against us and leave the country.”

—Exodus 1:8–10

The moisture-laden green fields, humid air, and flowing canals whose banks were filled with the bull rushes and palm trees of the Delta were a welcomed respite for the Pharaoh and his family, who relocated there from Thebes during the hot summer months. Their royal residences in Mennefer on the Nile, renamed from the older city of Hutkaptah, were an annual delight in comparison to the burning sun and blowing sand of the dry, arid, sparkling royal city of Thebes. The name Mennefer meant “enduring and beautiful” in the Egyptian tongue, which is why it was not only the capital of Egypt, but also the place where Theban pharaohs enjoyed respite at their summer palace. It was nearly a week’s journey north from Thebes to Mennefer, floating more than 400 miles with the northerly current of the Nile, which dispersed into the Delta and eventually emptied into the Mediterranean Sea. At least the trip to Mennefer was with the current, making the annual commute smooth and swift. Conversely, the journey back south against the river’s flow made their autumnal return to the city seem much longer and much more tedious.

Mennefer, also known as “The Good Place,” which eventually became known by its adulterated Greek name of Memphis, was an old and great city sprawling at the mouth of the Nile Delta, under the protection of its patron god, Ptah. It was originally named Inebou Hedjou, the city of “The White Walls,” built by Pharaoh Menes around 3000 BC along with the great temple of Hutkaptah, the “Enclosure of the Ka of Ptah.” Mennefer’s bustling port of Perunefer was thick with the noise and smells of industry, with workshops, factories, and warehouses lining the riverfront. Mennefer was the main distribution port for food all throughout the kingdom, whose cities, villages, and centers of population clung to the banks of the Nile from Nubia to the Mediterranean. Although stone was ported up from places such as Gebel el Silsila, Mennefer was considered to be the capital of mud brick making; boatloads of sun-dried, Delta mud brick shipped out every day to the numerous building projects up and down the river.

Memphis—the ancient city of Mennefer—as it appears today.

From both his palace in Thebes and his summer palace in Mennefer, Pharaoh Ahmose I (also known as Ahmoses I, Amenes, Aahmes, and Nebpehtyra), reigned from 1550 BC to 1525 BC, according to the Oxford Chronology of Egyptian Kings. Egyptologist and author David Rohl suggested a new chronology that would place Ahmose I’s reign from 1194 BC to 1170 BC,5 but this has been rejected by the majority of Egyptologists even prior to the release of radiocarbon dating released by the journal Science in 2010.6 Ahmose I completed the defeat and expulsion of the Hyksos and re-unified Upper and Lower Egypt, becoming the absolute ruler of Egypt. By ousting the Hyksos, he reestablished Theban rule and reasserted Egyptian power in the formerly subjugated regions of Nubia and Canaan. And he set about sweeping all remnants of the presence of the repugnant Hyksos from Mennefer.

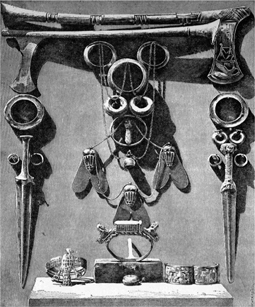

The jewelry and ceremonial axes found in the tomb of Queen Ahotep, mother of Ahmose I. The axe head depicts Ahmose I slaying a Hyksos soldier, and the golden “flies” commemorate his mother’s supportive role against the Hyksos.

So, the Hebrew people, who had come to Egypt several generations past to avoid the harsh famine in Canaan, found a new homeland, given to them by the Hyksos pharaoh. But now they were nothing more than a despised people who bore the guilt of association and benefit at the hands of the invading Hyksos Shepherd Kings. It was not a good time to be living in Egypt for these nomadic emigrants from Syria and Canaan; the new pharaoh, Ahmose I, saw them as a blight and feared that because they had grown so exponentially they would be a force to be reckoned with if not subdued immediately. So in great administrative reorganizations, Ahmose cleansed Egypt of the Hyksos influence and began massive new building campaigns to reconstruct Egypt in a new glory. He reopened the quarries that had lain stagnant for generations and opened up the mining in the Sinai, reestablishing the trade routes throughout Egypt, and improving the grand canal of the Pharaohs stretching east along the Wadi Tumilat down through Lake Timsah and the Great Bitter Lake to the Sea of Reeds, across the northern tip of the Red Sea and into the Sinai desert. Ahmose forcibly breathed the air of Egypt back into the lungs of the Nile Delta. Not only had he driven out the usurpers, but he would be the pharaoh known for building an even greater Egypt than had existed before. But all of this required the living, breathing, pulsing technological machinery of his day: the blood, sweat, and tears of a human workforce.

Not only did Ahmose I incorporate the talents and raw loyalty of his Egyptian craftsmen and workers, but he also found it in the Hebrews and other Asiatic peoples dwelling in the Delta region—a sizeable workforce of which he took great advantage.7 As previously described, there was no love for the Hebrews and other Semitic peoples living in the Delta, and Ahmose I and his successors imposed harsh labor on them, forcing them into servitude, pressing them into work camps in the quarries along the Nile and the copper and turquoise mines in the mountains of the western Sinai wilderness.

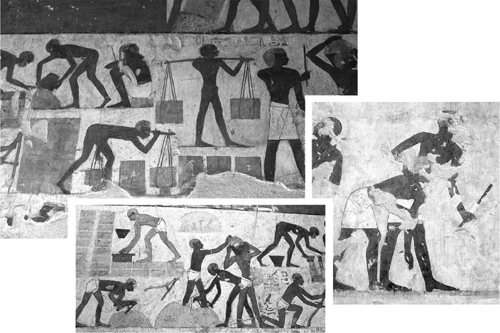

Semitic workers making mud brick from the walls of the Tomb of Rekhmire, Tombs of the Nobles, Luxor, Egypt.

Nearly a century later, Pharaoh Thutmoses III was still utilizing Semitic peoples as a workforce. Rekhmire, vizier to Thutmoses III, and subsequently to his son, Amenhotep II, left behind beautifully detailed paintings on the walls of his tomb among the Tombs of the Nobles in Thebes (current-day Luxor) depicting Semitic workers making mud brick and carving blocks. The accompanying hieroglyphic text reads: “He supplies us with bread, beer, and every good thing,” while the Egyptian task master is saying, “The rod is in my hand; be not idle!”8

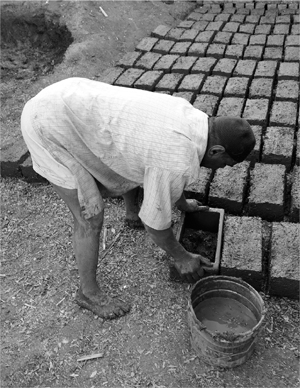

A modern-day mud brick maker in the village of el Kom, outside Luxor, Egypt.

Although it has been well established by Egyptologists throughout the last 200 years that much of the construction work carried out in ancient Egypt was by communities of indigenous workers whose entire lives were dedicated to the glory of their pharaohs,9 in the New Kingdom, we see a shift in workforce to that of pressing the foreign inhabitants of the land into enforced servitude. And it seems apparent that the offspring of those foreign workers were simply born into a veritable slave caste, proliferating the exponential population of the forced laborers. There are also many references to prisoners of war being hauled back to Egypt from foreign campaigns in Nubia, Syria, and Canaan, where soldiers and other inhabitants are brought to Egypt for the express purpose of pressing them into forced slave labor.

The big question is: Are any of these foreign-blooded slaves Hebrews? Are they the descendants of the family of Jacob that were given fertile land in the Delta region under the rule of foreign kings who had usurped the northern throne of Egypt? Although there is no direct evidence of Jacob’s clan and descendants, I think we have, via secondary archaeological evidence, established that this possibility flies off the top of the plausibility scale. And in a nation that didn’t give a lot of attention to the particulars of whom they considered as enemies of the state (other than to mention them by regional affiliation and origins, such as the term Asiatics so profoundly demonstrates), they did not separate them out by family clan names, such as “the children of Jacob/Israel.” And if they ever did, those records are lost to antiquity. But now, it seems highly improbable that any pharaoh or scribe would have called out the Hebrews; the descended family tree of a migrated group of Canaanite tribesmen by their family name of Israel was simply never recorded. And if Joseph and his father’s clan and his brothers were given the land in the Delta, those records, if they ever existed on papyri, are simply lost to the humid, flooding climate of the Nile Delta.

The questions of a Hebrew presence has to solidly rest on whether or not the books of Genesis, Exodus, Levticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy—the writings of Moses known as the Pentateuch, the Jewish Torah—can be accepted as historical documents, or at the very least, while being books of faith, present facts that can be established through plausible secondary archaeology. We have hit hard on this point already, but it is worth reminding ourselves again, right here, that just because an ancient document is “spiritual” or “religious” in nature, that should not preclude its contents from being considered as reliable history. But the proof is in the pudding, as the ubiquitous “they” contend. Establishing historical plausibility is then the primary means in establishing biblical authenticity of record.

American scholars William Albright and John Bright contended that the biblical record is reliable in its historical presentations. When coupled with secondary historical data, it gives us a very authentic picture of Hebrew history. In A History of Israel (1959), John Bright, a student of Albright’s, maintained this biblical authenticity. In the third edition of his book in 1981, he stated emphatically from a faith-based position: “There can really be little doubt that ancestors of Israel had been slaves in Egypt and had escaped in some marvelous way. Almost no one today would question it.”10

So what do you do when faith runs headlong into science? This is the ever-present debate that exists in every field of scientific study. Do we accept carte blanche the teachings in a book of faith? Or must we balance those teachings against what we know by research and scientific study? I think we all know the answer is in the latter. Acceptance by faith is a matter of heart and belief, whereas the examination of fact must be applied. A scholarly seminarian professor friend of mine once said, “Remember, in all of your historical research, you cannot forget to maintain the Bible as your filter.” This is good advice from a seminary professor, but it is clearly a statement of faith. Using the Bible as your only means of filtering historical data can lead to a dangerous end and sometimes to unfounded conclusions—no matter what you wish to be true or what aligns with your religious beliefs.

Scotty on his first ferry across the Nile from the west to east bank of Luxor (ancient Thebes) with Luxor Temple in the background.

In Luxor, Egypt, this last January, the authors were at dinner with a Muslim friend (we will call him Sayad to hide his identity). The topic of this book came up for discussion at the table, and we all had a sincere, frank dialog. In the discussion, Sayad, a business owner and overall intelligent man, asked questions and posited theories. But when it came to the bottom line, he raised his hands calmly and said, “The Holy Quran says it is so, and that is then fact.” We respectfully asked him how he would react if he learned that historical data contradicted or even controverted the writings in his holy book. He simply raised his eyebrows and in a sincere, friendly smile repeated his previous statement, to the word. We agreed that we respected his faith and would push the issue no further in that conversation.

But herein lays the problem with matters of faith: When seeking answers to historical mysteries and questions, we are not seeking truth. We are seeking fact. No matter what our faith may tell us, we must defer to available facts and data. This does not mean that there are not more things to discover on any given matter, but that when researching, all biases must be left at the door. For instance, in searching for facts that may establish the biblical record, the faith issue must be checked and balanced against historical data, and if the established, grounded data is in conflict with scripture, it must be concluded that the scripture is either completely wrong, or there are explanations and more data to be found. This is not an abandonment of faith and belief; it is a suspension of religiously held dogma in order to take an objective view of researched, uncovered data.

Conversely, the same must be said for science and academia. Simply because historical data already exists ought not to preclude the filter of religious work, as they represent a body of history all on their own. Any previously held acceptance of archaeological data, if contradicted or even controverted by faith-based data, must be open to the possibility that there may be more to the research than what meets the eye with black-and-white facts. It is the modus operandi of the academic community to label any faith-based argument that cannot be established by cold, hard fact as “wrong.” In a real sense, academicians can be as “religious” as those who operate by faith alone.

Agendas and preciously held belief systems must be left behind when researching for factual data. This does not mean they ought to be abandoned, for many discoveries are driven by the desire to either substantiate or disintegrate theoretical or faith-based claims. The key is to not be beholden to one or the other. A researcher simply has to be a researcher, even when it comes to the story of Moses and the Exodus, a thematical theory based on the books of three of the world’s major religions. The notion is that there is something to those stories as contained in those books—hence the two centuries of repeated quests of discovery into the topic. But neither academia nor faith should drive the search for fact. Academic positioning comes with the evidential proof, whereas faith needs no proof at all to substantiate what it believes.

Scandinavian minimalist Niels Peter Lemche states, “The silence in the Egyptian sources as to the presence of Israel in the country (is) an obstacle to the notion of Israel’s 40 years sojourn.”11

American scholar Bernard Batto said, “The biblical narrative in the books of Genesis through Joshua owes more to the folkloristic tradition of the ancient Near East than to the historical genre.”12

There is always presupposition brought to the table. The biblical scholars presuppose the scriptural tales are real history, while the academics presuppose they simply never really happened, but are part of folkloric tradition.

What we give you in these pages is a mix of the two. We cannot state emphatically that the faith story never happened, but we must adhere to current academic discovery, even if it contradicts issues of faith.

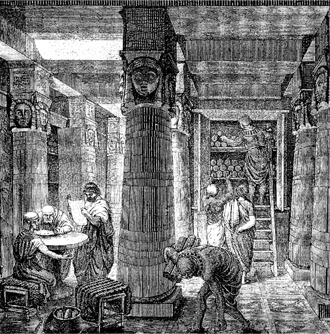

When Alexander the Great died in 323 BC, having “no more worlds to conquer,” he left the world in a very Hellenized state, in which the universal language of commerce was Koine Greek, the same language with which most of the biblical New Testament is written. As legend tells, the Macedonian Pharaoh of Egypt, Ptolemy II (309–246 BC), sponsored the translation of the Jewish Torah and related texts from biblical Hebrew into Greek for inclusion in the Library of Alexandria. The translation took place in several stages over many years, but the result was to give us the Septuagint, the Greek version of the Old Testament that is the basis for the Old Latin, Slavonic, Syriac, Old Armenian, Old Georgian, and Coptic versions of the Christian Old Testament.13 After the Torah, other books were translated throughout the next two to three centuries, but it is not even clear which book was translated when, or where that translation took place. There is even some evidence that some of the books included may have been translated more than once (into distinctly different versions), and then revised again from that point.14

King Ptolemy once gathered 72 Elders. He placed them in 72 chambers, each of them in a separate one, without revealing to them why they were summoned. He entered each one’s room and said: ‘Write for me the Torah of Moshe, your teacher.’ God put it in the heart of each one to translate identically as all the others did.15

One of the problems encountered with the Septuagint is that the quality and style of the different translators varied considerably from book to book, sometime offering up a literal translation, then sometimes jumping from paraphrasing to outright interpretative.16 This has caused many scholars to see the Septuagint as a work of not simply re-recording ancient Hebrew scripture, but of “rewriting” certain texts to support the national identity of Israel and appeal to the faithful adherents of Judaism.

It is from this Greek translation of the Old Testament that we have most of our current English version. Hebrew manuscripts still exist, but not in their original form. And it is this repeated translation of the Old Testament that has left us with questions as to authenticity and veracity to the original documents—if they existed at all.

An artist’s rendition of how the Library of Alexandria would have appeared in the time of Ptolemy II.

And, by the way, the legend doesn’t deal with the Septuagint itself, as we have copies of this document and many other forms. The legend is focused on whether or not it was Ptolemy II’s invite, or the 72 rabbis simply came begging on the doorstep of the Library of Alexandria, and were granted permission.

The skeptical/atheistic community’s periodical Free Inquiry takes the stance that none of it every really happened at all, and it was completely fabricated.17

So, in reality we have no real substantive proof of what Moses penned in his original books. Further, we have no hard evidence as to whether Moses even lived. According to the “true scientists,” we need to approach the notion of there being an historical Moses and an equally historical event known as the Great Exodus as if he never really existed in the first place. The absence of any direct evidence of existence, they will tell you, is the absence of existence. The biblical record is not direct historical evidence as it is a book of faith, and absent any historical record, there is, they conclude, no Moses. He is a figment of Jewish fiction, an element of Canaanite folklore. But, then again, so are Joseph, Jacob, the Hebrews, and all of the fanciful notions of Egyptian bondage, miraculous deliverance, and the conquest of the land of Canaan.

A sample of name erasure from a lintel above a spios on the banks of the Nile at the West Bank of the Quarries of Gebel el Silsila.

But all of this presupposes that the Bible and the writings traditionally held to be those of Moses have no real historical value. And as a result, you should, if you are a critical thinker of any sort, continually ask yourself why academia and science so discount the biblical record as having no historical value and no archaeological merit.

Nelson Glueck, a noted 20th-century Jewish archeologist whose work in biblical archaeology led to the discovery of more than 1,500 ancient sites, put it this way: “It may be stated categorically that no archeological discovery has ever controverted a single biblical reference. Scores of archeological findings have been made which confirm in clear outline or in exact detail historical statements in the Bible.”18

Not surprisingly—as some think of the biblical record as being inaccurate and rife with faith stories alone—when stacked up against non-biblical accounts of historical events, the scriptural narratives reveal unflinching veracity.19

Here is something to consider: Perhaps Moses, in accordance with our contention that he was thoroughly Egyptian, despite being born of Hebrew blood, simply wrote the book of Exodus in a very Egyptian style. He didn’t omit the names of the pharaohs because he was creating some sort of fiction, he left them out as to not give them life. In the ancient Egyptian way of thinking, the Life Eternal and the Resurrection in the Afterlife was achieved through the recording of the name for all eternity to witness. By deliberately leaving their names out of the book, perhaps Moses, in his own way, was writing them out of history.