THE HAPU THREAD

In the new light of day, one can only begin to imagine what the devastation must have been like and the effects it would have had upon the remaining population, the river having reclaimed its natural course and flood plains, washing away the debris and the remains of what was once Thebes. The sheer amount of dead, missing, and dying would have been far too much for what little infrastructure remained within this ancient society. The temples and its priests were unable to offer the help or assistance required due to their own desperation and inability to deal with such a catastrophe. This only added to the despair of the people; what was once a thriving community with clear lines of demarcation and structure now lay in tatters and chaos.

One could draw upon a contemporary experience, as many of us witnessed the devastating effects of a tsunami as it struck off the coast of Japan in 2011, the tsunami that hit Thailand in 2001, and the devastating hurricanes that annually hit landfall on America’s east coast. All of these natural catastrophes are being beamed around the planet instantaneously for millions to watch and respond to, with huge acts of generosity and kindness from the safety of our armchairs. As for ancient Thebes, she had only herself to fall back on; there were no international rescue crews dispatched to her aid, there was no United Nations relief, no mobile tents or other modern military equipment to save those who survived and provide the necessary shelter. For us, it is hard to imagine the consequences of not having such a well-equipped accident and emergency body or a FEMA organization that can deal with such global crisis. For the Thebans, they had only themselves.

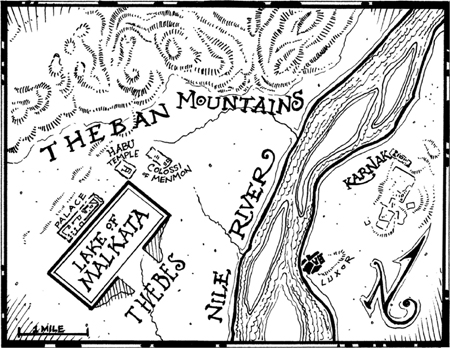

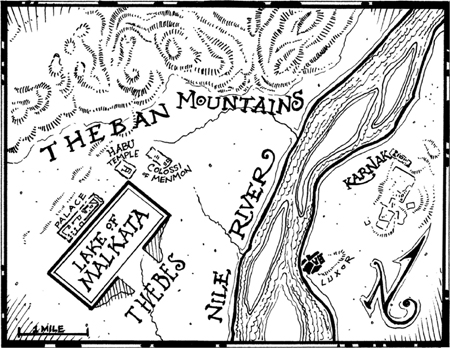

Ancient Thebes and the enormous Sacred Lake built by Amenhotep III.

The heat of the midday Egyptian sun in July usually goes well into the 100s. Combined with the lack of adequate shelter and supplies, those injured or suffering the effects of the flood would have soon become victims of circumstance, and the unbearable heat would have helped add to the death toll. The frail and young would be among the first succumbing to its effects, then after a few short days the water-borne diseases and pestilence would only add to the insurmountable problems that the survivors would have to deal with. Those who were injured would have succumbed to the unsanitary living conditions, increasing their chances of infections to their wounds, and subsequently hampering any healing process, but ultimately bringing death.

The tempest heat of Egypt is also a breeding ground for mosquitoes, flies, and other infection-spreading insects, all of which would have multiplied in the aftermath, feeding upon those who lay decomposing in the sun and the individuals who had no shelter from their now uninhabitable environment. Malaria and other blood-transported diseases rapidly spread among the survivors1, hampering any rescue operations and other associated tasks of survival. Within a short while the temple corridors would be teeming with those unable to deal with their illnesses. For sure I paint a pretty gloomy picture; however, given the state of rudimentary housing and limited infrastructure available to the Theban population at that time, it is reasonable to suggest such horrific and depressing details.

Either funeral pyres or mass graves would have been the only option available to the remaining Thebans.

As for the dead, there would be no time for the obligatory 70 days of laying in a bath of natron or the customary mummification process to be granted to all who had died that day.2 The tombs took far too long to excavate and the workshops that usually dealt with this matter were already full with the injured and dying. Either funeral pyres or mass graves would have been the only option available to the remaining Thebans. Given the option of committing the bodies to the Nile would have been abhorrent to the survivors, and given the nature of their death and the devastation that had been inflicted upon them, this would not have even been considered. The desert floor would prove to be an ideal location, but the ground would have taken days to dig through, and with the rise in epidemics, other diseases, and incessant harassment from the local animal population, the funeral pyres would have been an effective way of disposing the decomposing bodies.

I would like to draw your attention at this point to the “Admonitions of an Egyptian Sage”3 an ancient Egyptian papyrus that possibly dates to around the 18th or 19th Dynasty. Currently there is only one original copy, located in Leiden University, and it is known as Papyrus Leiden 344. It has unfortunately suffered considerable damage during its lifetime, which has left some significant gaping holes within its narrative, but also toward the characters to which it pertains. The original does not mention the name of the Pharaoh or a date, and the final outcome of the story is also unknown due to missing verses. However, the content of the papyrus holds certain key elements that directly pertain to the unfolding events that I have suggested and include the aftermath of such a scenario. Also, there are clear associations with the contents of Spell 1254 from the Book of Going Forth or more commonly known as the Book of the Dead, which have many associations with the biblical Ten Commandments that were handed down to Moses by the writing of God on the Holy Mount. We will deal with these texts later in the book.

So, if I may draw your attention to Appendix A and the “Admonitions of an Egyptian Sage,” lines 46 and 47 speak of the Nile overflowing and the land becoming unusable and its fate unsure. If the embankments to the west that protected the agricultural fields during the flood season were in fact broken, as I have suggested, then the land would become unsuitable, and there would be a shortage of harvestable crop and sustainable food supplies for the cattle and other livestock throughout that season. Please remember that the banks of the River Nile to both Upper and Lower Egypt are extremely flat, and in most places lie beneath the flood levels. These embankments, especially on the boundaries of the cities, would have allowed the continued planting and tilling of the arable land, irrigated by the very successful and naturally fed canals, which also acted as routes of transportation, communication, and military applications.

Various archaeological projects throughout the years have carried out investigations to determine the exact location of these ancient canals and how they fed one another, but more importantly how they would have been navigated during the flood season. In addition, further investigations were needed to explore the removal of the buildup of silt and accumulated rubbish, which would have been necessary to aid the continued use of them as a strategic waterway system, serving the entire city and its society.5 Without these canals, the east and west banks would be cut off from one another during the flood season, effectively reducing the capacity to rule and govern the populace. Thebes relied heavily on these canals for the reasons I have presented, and they would have been invaluable during the crisis, helping with the transportation of supplies and ferrying the injured and dead to and from their respective areas. And given the devastation inflicted upon the fleet of cargo ships and other small boats moored at the harbors of Thebes, the canals would have been navigated by much smaller vessels (nothing more than rafts really), but capable of completing the tasks at hand.

Again, I refer to the Admonitions, this time lines 54 to 65, which refer to the river as a place of entombment and that blood is everywhere. I of course relate this to the immediate aftermath of the event where pools of blood began to gather, and the rivers increased in height, washing the floating bodies northward away from Thebes. Look at the similarities between lines 54 through 65 and the biblical narrative of the first plague:

“Admonitions of an Egyptian Sage” lines 54–65:

Verily, the heart is horrified,

For affliction pervades the land,

Blood is everywhere,

And the death-shroud summons,

Though one’s time has not yet come.

Verily, countless corpses are entombed in the river;

The waters are a tomb, and the place of embalming is the river.

Verily, the Nobles are in lamentation, while the paupers are in glee,

And every city says, “Let us drive out the mighty from our midst.”

Verily, the people are like Ibises, for filth pervades the land,

And there are none at all in our time whose garments are white.

Exodus 7:19:

Then the Lord spoke with Moses, “Say to Aaron, ‘Take your rod and stretch out your hand over the waters of Egypt, over their streams, over their rivers, over their ponds, and over all their pools water, that they may become blood. And there shall be blood throughout all the land of Egypt, both in vessels of wood and vessels of stone.’”6

Is it coincidence that the ancient texts and biblical narrative talk of one and the same? The source or origin of the “Admonitions” has been speculated for many years by various academics and educational institutions alike. Some suggest a reference to early dynastic problems within Egypt, and that the inclusion of poetic narrative throughout the ensuing years has led to the final copy that we posses today, painting a more dramatic picture than that which was intended in the beginning. Whatever the origin, there are unmistakable correlations between the scenario of the apocalyptic disaster, the biblical narrative of Exodus, and other historical events that have taken place in Egypt’s vast ancient history.

What could Pharaoh or his political court of nobles have done to prevent such a disaster? Could they have prevented it? Could it have been avoided? These questions can never really be answered, but the effects of such an apocalyptic rage and its subsequent aftermath can be. Given the size and popularity of Thebes during the 18th Dynasty, it is fair to speculate that the population was as diverse as it was in number. Such a terrible set of circumstances would have brought many of the survivors together within specific groups. But most likely, the royal house would have remained singled out among them because of its high-ranking position within the overall community. Would Pharaoh be the vent of the peoples’ anger, as they looked to him as the personification of God on earth—the very same God that was supposed to save them from such terrible evils and prevent chaos from reigning down upon them? Given the amount of protection Pharaoh would have had at any given moment, I doubt that the remnants of the hardcore commoners railed as an angry mob against him or his family; rather, a political or religious banishment may have occurred in such a series of events. However, this does not rule out the possibility of small skirmishes that were directed at the royal house.

The ancient workers’ city was washed away and its heart was hollowed out.

The ancient Egyptian society was not exactly a complex structure; rather, the class system was very much adhered to, each man and woman knowing their place within the community and their responsibilities to the overall religious foundation that oversaw the smooth running of the state. Their children followed in the footsteps of their fathers, entering their respective trades and professions. It was this class system that would have played an important role in the initial days after the disaster. Groups of well-defined class status, religious belief, and skill sets would have begun to emerge within the depressed community, each having their respective leaders. These groups may have been responsible for the historical events that I suggest might have followed this catastrophe, which we will explore later.

As the days passed, the dead and dying would become one as the Underworld surfaced within Thebes. As the last of their personal reserves dwindled away, people would begin searching for other supplies, unable to feed themselves or the injured who had survived the disaster. Eventually, due to personal responsibilities, the fit would be unable to offer support or medical assistance to those who were wounded, and the sick would eventually join those who lost their lives in the initial wave of destruction. Law and order would have broken down; vigilante groups would soon form, protecting what little reserves of supplies they had left. Marauding gangs of thieves and looters would take over the land, stealing and pillaging what they could find among the remains. It would be fair to say that the neighboring cities would have offered assistance to Thebes. The established trade routes would have made easy pickings for those who hid and ambushed the support and aid that filtered along its dusty paths. The Medjay army and the judicial court system would be unable to cope with the increased criminal activity, forcing the law-enforcement bodies to carry out lethal punishment to those found breaking the law. Line 42 of the Admonitions speaks of the archers being ordered and that evil has spread everywhere.

The empty graneries stand behind the colossal ruins of the Ramesseum in Luxor.

The priests would have been an easy target, with their granary stores and other associated food stock piles; even though both Ipet-resyt (Luxor) and Ipet-isut (Karnak) had been decimated by the flood, there would have been areas unaffected by the waters. The towering massive stone buildings would have supported the community after the crisis; a hierarchy would have developed within the sacred walls, and people would have sought them out for shelter. Another option would have been the tombs secreted in the Theban Mountains, offering a respite from the harsh rays of Ra, but most importantly they were secure and could be defended in times of need.

The army and the Pharaoh’s own Medjay would be unable to police or contain the civil unrest as the days of horror turned into weeks of pain and misery. Neighboring cities such as Dendera, Hierakonpolis, and Medamud would have been overwhelmed by the survivors as they expanded their search for food and shelter. The displacement would have been nothing less than an Exodus to a certain extent (excuse the pun here). But again, I draw upon historical comparable material, where history shows us that people will do almost anything to safeguard their families and provide the basic form of necessities to aid their survival. In times of need, mass migration in any given direction in search of shelter and food is usually the result of a breakdown within the society in which they usually reside. These migrations only add to the turmoil and place extreme stresses upon neighboring communities and their own resources. Unable to cope with the amount of people, these smaller districts ultimately end up joining the migration in search for further food and sustainable resources.

Livestock that survived would be scrambling for the little vegetation that endured the waters. Although the diminished livestock would now be limited to the higher grounds that skirted the desert’s edge, foraging for what little it could find, it, too, would become susceptible to the contaminated water supply, bringing about certain bovine diseases that could be transmitted from beast to man. Blow flies, ticks, mange, and other ailments that afflicted livestock would be heightened by their situation, compounded and worsened to the extreme. Flies and mosquitoes would transport chronic gastrointestinal illness and blood-borne diseases that would rapidly spread among those foraging for the meager pickings. Soon, Thebes would become an open-air cemetery, the land of the dead, in more than just words and metaphor. Of course, the most important commodity, water, would be the hardest to come by. The amount of pollution in the pools and waterways that ran through the remains of Thebes would have been so badly contaminated that it would have been deadly to drink due to the microscopic evils that would wreak havoc once ingested, and most certainly bring death upon its drinkers.

We must pause for a moment and ask ourselves how the royal palace kept its occupants hydrated during such a time. One could suggest that the waters up-river were clean and free of the debris and aftermath that contaminated the waters below. It might also be plausible that an ongoing supply of fresh drinking water was ferried into Thebes via the river by smaller vessels and by land across the higher desert ground.

As we have discussed, the breakdown in the class structure would have led to immeasurable chaos running through what was left. But what about the aristocratic families and their inability (through upbringing) to cope with such a calamity? Having lived such a pampered life, surrounded by servants and serfs alike, it is difficult to ascertain whether they would have survived the first couple of weeks having to fend for themselves. Their splendid villas perched high up on the desert plain, with their ornamental gardens, planted orchards, and central ponds, would have been one of the first vestiges of those who sought shelter and security. Their homes overrun with commoners, I find it hard to accept that they would have opened their doors freely and willingly. I would suggest that most would have sought the safety of the royal palace and that of the Medjay. However, even the royal palace could not retain the sufficient supplies and provisions to sustain such a large amount of people behind its closed and reinforced doors. Again, we can read certain verses within “Admonitions” that pertain directly to this predicament, in which it states that the nobles who once slept in beds now slept upon the floor and those who had no beds now slept within the mansions. An ironic rags to riches tale, to say the least.

Though the first couple of weeks after the catastrophe would have formed specific groups, which probably facilitated the overall survival of their members, Thebes still fell quickly into lawlessness and chaos. Further into the book I discuss the emergence of the four main groups, which I believe are the basis for the biblical Exodus story.