THE SENENMUT THREAD

Driving across the Egyptian desert, east of Cairo and the Nile Delta, en route to the Sinai border was all at once beautiful and yet extremely boring. Not in a disinterested sort of way, but something like the feeling you get when driving through Iowa, where the first few miles of flat cornfield are a beautiful thing to behold. But at about mile marker #99, you long to see a hill or a tree or a winding river. The Egyptian desert was a lot like that: flat sandy terrain as far as the eye could see, punctuated by the occasional dune or rocky outcrop. It made us think about how that journey must have been by foot. It took us a little more than two hours to reach the Suez Canal and the Sinai border, just to the north of the Red Sea, but if I had been asked to walk that distance, carrying everything I could take with me in a pack on my back, along with my wife, my parents, my small children, and my goats, sheep, and whatever else I could put my hands on while bugging out, that trip would have been much different and much longer. Then place my little entourage in a massive, clustered line of 599,000 more groups just like mine, and you can exponentially increase the walking time by a factor of impossible to nil. Then add to the equation that we are all slaves or prisoners fleeing our overlords and masters, never quite sure if they will be in hot pursuit or not. Add to that the lack of water and food, the hot sun beating down on us, the fact that none of us, as slaves, have ever been camping or know a damned thing about desert wilderness survival techniques, and you have the makings of an epic...disaster.

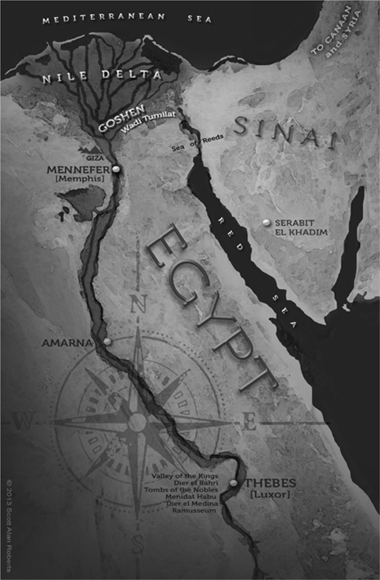

From Cairo to Sinai.

When Moses led those people out of Egypt, he had to have a plan. The biblical passage tells us that it was all divine, with God providing the way, as well as the miraculous defense and divinely provided food from the sky and water from the rock. It would take a heaping serving of faith to swallow that story whole. But that is precisely what the biblical story offers up on a Golden Calf–shaped platter. So if this event truly took place, how are we to understand it in human terms, sans the theophanized manipulation of a divine story that turned into historical legend and finally became the stuff of religious mythology?

What really happened that first Passover morning when Moses told the Hebrews to “Be ready to leave in a moment’s notice”? Planning to hike 20 people across the desert on a foot tour of sites takes weeks of preparation and meticulous planning. All Moses told the Hebrews to do was slather sheep’s blood on their door posts and lintels, and be ready to head out for the Promised Land in the morning. But don’t forget to go to your Egyptian neighbors tonight and tell them you want to “borrow” (wink, wink, nudge, nudge) all their gold. You aren’t coming back, so the word borrow is a bit of a misnomer. And what is a massive population of slaves, adding up to nearly 1.2 million people, doing living mixed in with their Egyptian neighbors? And if they are all slaves, why do some of them have gold? And if this is a slave community in the land of Goshen in the fertile Nile Delta region, how close are the slaves to the non-slaves, if all you have to do is walk next door and ask for a cup of yeast—oh, and all your valuables, too? What power did the slaves have over the common folk of Egypt that they’d just give you everything you asked for?

Ah, it was the plagues. They were living in such fearful awe of you and your leader, Moses, that they’d give you the clothes off their backs if you asked, just to get rid of you and not suffer anymore at the hand of your god.

Although I am being slightly tongue-in-cheek here, doesn’t this make you stop and think about how it all really came down? How were the logistics carried out? Which way did they go and what was the plan when they crossed the border with the pyramids in the rear-view mirror? To some this can sound like an adventure, but to others, this would be a veritable hell.

Imagine that you are so poor that you don’t even amount to impoverished. Your bodies are blackened by the desert sun, and the sweat of your labor stings in the wounds left by the lashes you received by your taskmaster earlier today. The only parts of your body left without color are your mud-covered legs that were sunk into the mud pits while making bricks—thousands and thousands of bricks every day to meet your tally, relentlessly stomping the straw and stubble into the mud to add strength to the final dried product.

Imagine carrying dried brick to the boats or the carts for transport around the country, or imagine being part of a crew that hauls blocks of quarried stones, dragging massive sandstone blocks weighing hundreds of tons. The work is hot, sweaty, and draining. And all you have to look forward to is the next day where it will all be the same, over and over and over again. You are not a human being; you are a slave. The only care you receive is as a commodity, a cog in the great machine that is the building power of Egypt.

WHEN HER STEPSON/NEPHEW, THUTMOSES III, WAS TOO YOUNG TO ASCEND THE THRONE ALONE, HATSHEPSUT BECAME HIS CO-REGENT. BUT WITHIN SIX YEARS, SHE NAMED HERSELF “KING” AND RULED AS THE PHARAOH OF OF EGYPT CLAIMING THAT IT HAD BEEN THE WILL OF HER FATHER THAT SHE SHOULD REIGN.

IT IS SCOTTY’S CONTENTION THAT THIS REMARKABLE WOMAN WAS NONE OTHER THAN THE DAUGHTER OF PHARAOH THUTMOSES I, THE SAME “PHARAOH’S DAUGHTER” MENTIONED IN THE BOOK OF EXODUS, AND THAT IT WAS SHE WHO FOUND THE BABY MOSES IN THE BULRUSHES ON THE NILE’S BANKS.

HATSHEPSUT’S TEMPLE DJESER DJESERU AT DEIR EL BAHRI LUXOR, EGYPT

CARTOU CHE OF THUTMOSES III FROM DEIR EL BAHRI

ALL PHOTOS IN THIS SECTION COURTESY OF THE AUTHORS

SENENMUTWAS A COMMONER WHO BECAME HER DAUGHTER, NEFRURE; GRAND VIZIER OF EGYPT; “MOTHER’S BROTHER”; HEREDITERY CROWN PRINCE OF EGYPT, ALONG WITH 88 OTHER TITLES BESTOWED ON HIM BY HATSHEPSUT. AS HER ROYAL ARCHITECT HE WAS SAID TO HAVE BUILT DJESER DJESERU, HATSHEPSUT’S TEMPLE AT DEIR EL BAHRI, AND LEFT BEHIND AT LEAST TWO UNFINISHED TOMBS OF HIS OWN.

SENENEMUT COMPLETELY DISAPPEARED FROM EGYPTIAN HISTORY WITHOUT A TRACE, LEAVING BEHIND TWO UNUSED, UNFINISHED TOMBS. ALL IMAGES OF BOTH HE AND HATSHEPSUT WERE ERADICATED BY AMENHOTEP II, SON OF THUTMOSES III.

SENENMUT LEFT BEHIND NINE STATUES OF HIMSELF HOLDING HATSHEPSUT’S ROYAL DAUGHTER, NEFRURE, IN A LOVING EMBRACE.

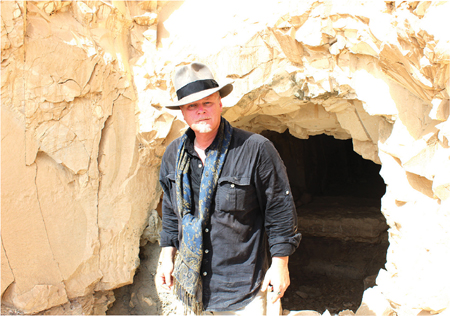

SCOTTY EMERGES FROM A TOMB HIGH IN THE NORTHERN CLIFF FACE ABOVE DEIR EL BAHRI, WHERE, UNTOUCHED FOR NEARLY 3,500 YEARS, ANCIENT PORNOGRAPHIC GRAFFITI DEPICTING SENENMUT AND HATSHEPSUT STILL ADORNS THE WALLS OF THE CHAMBER, WHICH WAS ORIGINALLY USED AS A REST HOUSE BY ANCIENT WORKERS ON THE TEMPLE BELOW.

THE AUTHORS STAND BENEATH THE MUD BRICK ARCH ENTRANCE TO THE TOMB OF MONTUEMHAT, THE FOURTH PROPHET OF AMUN (TT34), WITH DEIR EL BAHRI IN THE BACKGROUND.

THE NORTHERN CLIFF FACE ABOVE DEIR EL BAHRI

TEMPLE OF AMENHOTEP II PHARAOH OF THE EXODUS KARNAK TEMPLE COMPLEX, LUXOR, EGYPT

BACKGROUND: FROM THE WALLS OF DEIR EL BAHRI, HATSHEPSUT’S TEMPLE

ABOUT 30 MILES EAST OF THE RED SEA IN THE HEART OF THE SINAI WILDERNESS LIES THE “MOUNTAIN OF GOD” SPOKEN OF IN THE BOOK OF EXODUS. ATOP ITS PLATEAU ARE THE ANCIENT RUINS OF THE TEMPLE OF HATHOR, THE COW GODDESS OF EGYPT.

IT WAS ON THE DESERT FLOOR BELOW THAT THE CHILDREN OF ISRAEL MADE A GOLDEN CALF TO WORSHIP IN THE ABSENCE OF MOSES, WHO HAD GONE TO THE MOUNTAIN TOP TO CARVE THE TABLETS OF THE LAW ON STELE, WHICH WERE ENGRAVED ON BOTH SIDES.

RUINS OF THE TEMPLE OF HATHOR ATOP SERABIT EL KHADIM

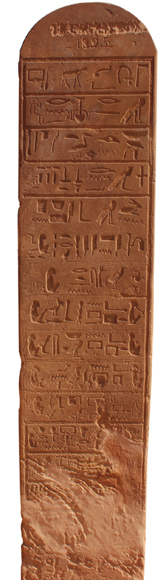

BACKGROUND IMAGE: THE CLIMB UP SERABIT EL KHADIM AND STELE (INSET).

HATHOR ATOP SERABIT EL KHADIM

CAVE OF HATHOR

THE AUTHORS AT THE TEMPLE OF HATHOR

THE AUTHORS “ENGAGED” IN MUD BRICK MAKING

DR. WARD DESCENDING THE “NILEOMETER” AT MEDINAT HABU

BACKGROUND IMAGE: THE WALLS OF THE TOMB OF RAMOSE, TOMBS OF THE NOBLES, LUXOR, EGYPT

FROM THUTMOSES III’S SANCTUARY AT KARNAK, ONE CAN SEE HATSHEPSUT’S DEIR EL BAHRI THREE MILES AWAY, STRAIGHT WEST ACROSS THE NILE, THROUGH THE DOORWAY OF THE SACRED BARQUE SANCTUARY.

AVENUE OF SPHINXES LUXOR TEMPLE

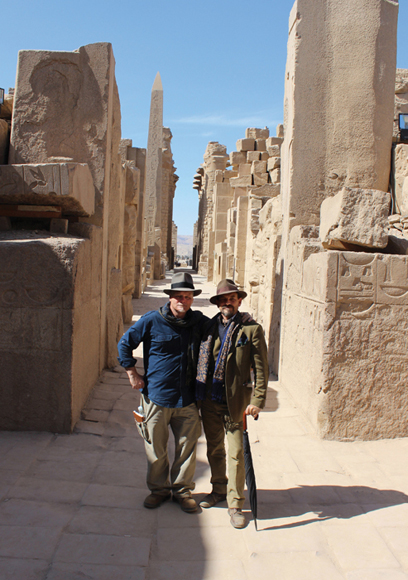

SCOTTY ROBERTS AND DR. JOHN WARD STANDING AT THE ENTRANCE TO THE SIXTH PYLON

And there is despair. There are no songs from home, because this is your home, and has been your peoples’ home for the last 300 years. There is nothing but hope that you will someday be freed, or someday die. That is your existence, which is spoken about in Exodus 1:12–14:

12b ...the Egyptians came to dread the Israelites 13 and worked them ruthlessly. 14 They made their lives bitter with harsh labor in brick and mortar and with all kinds of work in the fields; in all their harsh labor the Egyptians worked them ruthlessly.

According to the biblical account, Moses/Senenmut fled Egypt after killing the task master he witnessed beating a Hebrew. The passage in Exodus 1:15 tells us that “when the pharaoh heard of this, he tried to kill Moses, but Moses fled from pharaoh and went to live in Midian.”

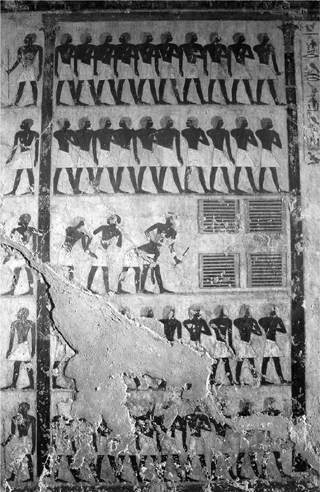

A tally of Semitic slaves and their task masters, also found in Rekhmire’s tomb, Tombs of the Nobles, Luxor.

Is this passage speaking of Hatshepsut? Was it she who wanted to take the life of Moses in exchange for the life of a task master who was one step above the status of a slave? Or was this task master someone of greater status than the Bible tells? Rekhmire, Grand Vizier of Egypt under the reign of Thutmoses III, was someone who held great rank, but was also referred to as a task master who held the rod with which a worker would be beaten if he did not keep up with his tasks. Now, for the record, I am not suggesting that Rekhmere was the task master killed by Moses, as he lived through the end of Thutmoses’ reign and into the reign of his successor, his son Amenhotep II. But I only cite the Grand Vizier as an example of someone who could also be literarily referred to as a taskmaster,1 albeit the one that is at the highest level or nobility over all other officials. What I am suggesting is the possibility that Moses murdered someone who was much higher up in the chain of command, and that could be a reason he was facing pharaonic retribution.

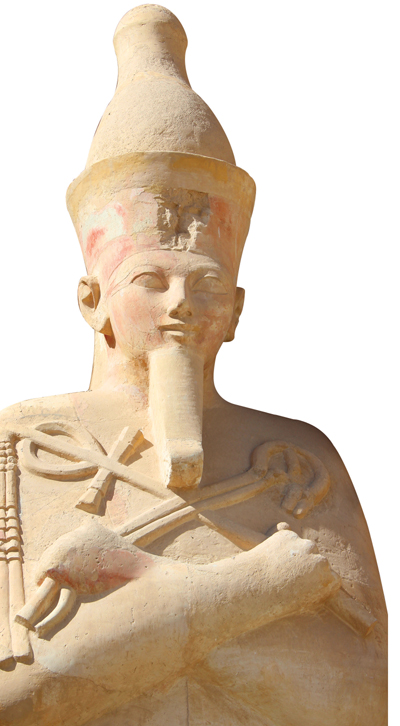

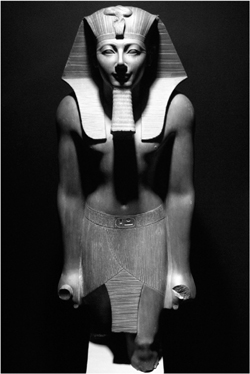

Pharaoh Thutmoses III.

The other reason Pharaoh was going to kill him is because this wasn’t Hatshepsut at all, but the co-regent, deposed pharaoh, Thutmoses III. When Moses/Senenmut murdered the task master, he exploited the Semitic blood of Moses as an example of what the Hebrew slaves were capable of and justified eliminating his political opponent. Again, this is speculative but highly probable under the political circumstances that existed at this time in Egypt.

So, Moses/Senenmut flees into hiding. He ends up in Midian, which still remains a mystery region today, but it is assumed it is in the northeast Sinai, but some have placed it in the Sudan to the south of Egypt. It is here that Moses marries the daughter of the pagan high priest, Jethro, named Tzipporah. He lives as a shepherd for the next four decades. No matter what the facts are behind the murder of the task master, it is clear that Moses/Senenmut is completely content with his decision to never see Egypt again. Yet, Midian seems like such a close place, logistically, to hide out. By car, it is a handful of hours through desert highways. By foot, however, it is weeks of travel along the ancient trade routes.

After 40 years in Midian, the memories of Egypt more than likely faded to a burning picture in Moses’ mind. But Midian was not so backwater that it would not have received news of what was happening in the world. It may not have come often, but it was sure to have reached the tents of the high priest and sheik of Midian, who no doubt conducted trade with traveling merchants and caravans. But Moses, it seems, was oblivious to the politics back in Egypt, for when at the burning bush, he recited to God his excuse that he could return to Egypt on account of the pharaoh seeking to kill him there. God seemingly had to assure Moses that all who were seeking his life were dead and buried.

I am never one to want to explain away the miracles of the Bible. Academia and science would have one believe that those are merely things of a faith-based approach, and they are given no real credence in the search for fact. As a pragmatist and researcher, I want to know if the entire story bears the weight of fact and is sustainable by historical evidence, and that includes the biblical passages that speak to miracles and wondrous deeds of the Divine. But in so doing, to remain an out-of-the-box thinker, I would have to come to a different conclusion regarding the deity in the biblical text. As a pragmatist, if I am going to accept that one deity has miraculous abilities, I would have to acquiesce that other deities in other religions may also have equal abilities, so generally, the scholarly academic will side-step the entire issue and look for more solid answers that fall handily outside the realm of divine magicks. But in this case, I think it is important to take a brief look at Moses’ epiphany at the burning bush in Exodus 3:1–15:

1 Now Moses was tending the flock of Jethro his father-in-law, the priest of Midian, and he led the flock to the far side of the wilderness and came to Horeb, the mountain of God. 2 There the angel of the Lord appeared to him in flames of fire from within a bush. Moses saw that though the bush was on fire it did not burn up. 3 So Moses thought, “I will go over and see this strange sight—why the bush does not burn up.”

4 When the Lord saw that he had gone over to look, God called to him from within the bush, “Moses! Moses!”

5 “Do not come any closer,” God said. “Take off your sandals, for the place where you are standing is holy ground.” 6 Then he said, “I am the God of your father, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac and the God of Jacob.” At this, Moses hid his face, because he was afraid to look at God.

7 The Lord said, “I have indeed seen the misery of my people in Egypt. I have heard them crying out because of their slave drivers, and I am concerned about their suffering. 8 So I have come down to rescue them from the hand of the Egyptians and to bring them up out of that land into a good and spacious land, a land flowing with milk and honey—the home of the Canaanites, Hittites, Amorites, Perizzites, Hivites and Jebusites. 9 And now the cry of the Israelites has reached me, and I have seen the way the Egyptians are oppressing them. 10 So now, go. I am sending you to Pharaoh to bring my people the Israelites out of Egypt.”

11 But Moses said to God, “Who am I that I should go to Pharaoh and bring the Israelites out of Egypt?”

12 And God said, “I will be with you. And this will be the sign to you that it is I who have sent you: When you have brought the people out of Egypt, you will worship God on this mountain.”

13 Moses said to God, “Suppose I go to the Israelites and say to them, ‘The God of your fathers has sent me to you,’ and they ask me, ‘What is his name?’ Then what shall I tell them?”

14 God said to Moses, “I am that I am. This is what you are to say to the Israelites: ‘I am has sent me to you.’”

15 God also said to Moses, “Say to the Israelites, ‘The Lord, the God of your fathers—the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac and the God of Jacob—has sent me to you.’”

Although at first reaction, one might be tempted to ask Moses what brand of peyote they were selling over there in Midian, it is clear that he is recording his own, personal spiritual experience. He is the only one there, and no one else hears or sees what he is experiencing.

Serabit el Khadim, the “Holy Mountain of God” from the book of Exodus.

There are a couple of interesting things to take note of in this passage. Now, as I mentioned previously, I am not one to offhandedly reject the notion of a miracle, nor am I one to dismiss the possibility of the Divine, but those are things that create quagmires all on their own when you engage in historical research.

When John Ward and I were in the Sinai in January 2013, we had the privilege and unique experience of visiting a mountain that we both believe is the “Holy Mountain of God” mentioned in the Exodus passages. We drove from Cairo straight east to the northern tip of the Red Sea, driving beneath the Suez Canal and crossing the border into Egyptian Sinai, approximating on paved highway the route the Hebrews took when leaving Egypt (which I believe began in the Delta region from the biblical land of Goshen, the place given to the sons of Jacob/Israel under the watchful eye of Joseph). We then turned south and followed the traditional path of the Hebrews along the eastern coastal road for about an hour and then turned inland to the east for another hour or so. Situated there is a low mountain with a flat plateau on top. At one end of the plateau are the ancient ruins of the Temple/Sanctuary of Hathor, the Egyptian cow goddess of joy, feminine love, and motherhood. We spent the night as guests of Bedouin Sheik Barakat, who put us up in one of his tattered-but-sturdy Bedouin tents, which I suppose was just fine for the climate. We were fed a sumptuous meal, and given pillows and thick camel hair blankets to wrap up in on the cool desert floor. In the morning, we climbed to the top of Serabit el Khadim, a mountain that served as a sanctuary memorial site for the workers in the surrounding copper and turquoise mines. We also met with a guardian of the Egyptian government named Moustafa Rezek. He is a man who has archaeological authority over the entirety of the Sinai and hiked with us up the side of the mountain, taking us to the top.

John Ward and Scotty Roberts with their host, Sheik Barakat, at Serabit el Khadim.

On the way up, the young college-aged lads who worked for Rezek walked alongside me as we neared the top. Their English was a bit rough, but we communicated just fine. We got into small talk, and they humored me by calling me a “great steed” for my tenacity in climbing to the top. (As a side note, these boys could have run up and down that mountain twice before I ever made it to the top—oh, to be young again!) I asked them if they meant “great stud!” They nodded their heads and said, “Yes! Great steed!” So I let it go at that. But what happened next is the important point I want to make here. One of the boys stepped off the path and bent low to pick a handful of some sort of white, thorny-looking plant. He brought it to me and said—without having any idea of what we were writing in this book—“Do you know what this is? It is a plant that is very valuable to us (Bedouins). You know why? You can light it and it never stops burning. Good for long time.”

My mind, as you can probably predict before reading the next line, went directly to the burning bush passage in Exodus: a bush that burns but is not consumed.

Now, as I stated, I am not one to explain away the miracles of one religion or another, but when you can find indirect yet plausible answers to biblical miracles, it just seems to establish plausibility. Although I wouldn’t mind finding proof of the miraculous, this little tidbit of information seemed to not only solidify a small part of the biblical story for me, but it seemed to have a bolstering affect on my faith.

I found myself asking if perhaps what happened to Moses was a spiritual experience that took place at a fire built of this stuff. Sure, it doesn’t explain anything, nor does it add or detract from the biblical narrative, but it certainly made me consider the possibilities.

So, Moses hears God’s voice and he starts to make excuses to this presence in this burning bush disguise. Then, in a bid to find the secret name of God, which is part of many ancient cultures’ spirituality—the gods have secret names, and if you can find out what they are and speak them, you can have some power over that deity—so Moses asks the question, “Who shall I say sent me?” And God answers in a very peculiar way, “Tell them ‘I Am’ sent you. ‘I am That I Am.’”

I was reading a recent article by Egyptologist and author David Rohl. He was writing about the Tower of Babel, and made reference to Moses’ encounter with God in the burning bush. He had some very interesting linguistics on this phrase “I Am That I Am.”

Sumerian literature identifies the god who warns Gilgamesh of the impending flood as Enki... Enki’s Akkadian name was Ea (pronounced Eya). The Hittites referred to him simply as Ya.

If we translate the mysterious “I am who I am” of Exodus 3:14 back into Hebrew we discover perhaps the most remarkable of all biblical plays on words. What Moses heard was “eya(h) asher eya(h)”—the “h”s are silent. This does indeed mean “I am who I am” but it can also be translated as “I am the one who is called Eya.” This gives a whole new meaning to God’s subsequent instruction to Moses. When the exiled prince of Egypt says “Behold, if I go to the Israelites and say to them, ‘The god of your ancestors has sent me to you,’ and they say to me, ‘What is his name?’ what am I to tell them?” the reply from the burning bush is: “This is what you are to say to the Israelites, ‘Eya (not ‘I am’) has sent me to you.’ You are to tell the Israelites, ‘Yahweh, the god of your ancestors, the god of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob has sent me to you.’”

Yahweh was, from that moment, to become the new name of the Mesopotamian deity whose original Semitic name was Eya. The god of the Hebrew ancestors can thus be traced back to a great Sumerian deity...whose most important title was Enki, the “Lord of the Earth.”2

Moses incorporated into his building of the Jewish religion everything he learned in life, from Egyptian to Sumerian. And here we have just learned how it was that he incorporated so much Sumerian literature into building Judaism: It was the same god that he had found in the cuneiform tablets. In a very real sense, God in the form of the burning bush just announced to Moses, “I am that Enki they have spoken of! That god Enki, known as Ea, is really ME! That’s what you tell the Children of Israel.”

I have maintained that when Moses left Egypt, although born of Hebrew blood, he was thoroughly Egyptian. I use the same comparison when I say that although my blood is Welsh/Scot, I am thoroughly American, as my family has lived in this land since my ancestors settled here 300 years ago. Moses brought with him all the wealth of the Egyptian royal educational system, and he combined that with everything he was to learn in Midian during the next 40 years of his life regarding the different cultures of the area and the religions of the Sinatics, the Canaanites, the Syrians, and everyone in between.

Empowered by his faith in God, into the courts of Pharaoh marches Moses and his older brother Aaron. Moses demands that Pharaoh let his people go.

But on the way back to Egypt, we find a very odd passage in Exodus 4:21–26, and there is a lot of debate over what really happened:

21 The Lord said to Moses, “When you return to Egypt, see that you perform before Pharaoh all the wonders I have given you the power to do. But I will harden his heart so that he will not let the people go. 22 Then say to Pharaoh, ‘This is what the Lord says: Israel is my firstborn son, 23 and I told you, “Let my son go, so he may worship me.” But you refused to let him go; so I will kill your firstborn son.’”

24 At a lodging place on the way, the Lord met Moses[b] and was about to kill him. 25 But Zipporah took a flint knife, cut off her son’s foreskin and touched Moses’ feet with it.[c] “Surely you are a bridegroom of blood to me,” she said. 26 So the Lord let him alone. (At that time she said “bridegroom of blood,” referring to circumcision.)

—Exodus 4:21–26 (Authors’ note)

This one might be best left for theological debate, but not anyone I have queried on this passage is sure of its direct meaning. However, the one meaning that keeps rising to the top, and it is very legalistic in nature, is that Moses had been disobedient for not circumcising his son in accordance with the Law. The only problem is that the Law did not yet exist, as it was Moses who was to record it later. So, apparently, according to some theologians, we are to read more into the account than what it actually tells us, and the God of the Old Testament was the kind of God that would bully those he called to follow him. I don’t read anything in the passage where God, in all his glorious conversation with Moses from the burning bush, says anything to him about circumcising his son or Moses’ life would taken. That might sound a bit cynical and harsh, but if you have a better translation of this passage, we’d certainly be open to hearing about it. So we’ll simply leave this one standing as is. It’s a clearly religious issue taking place in the passage, and although it may be pertinent to the biblical story, it has little bearing—at surface value—to the more archaeological questions for which we are seeking answers.

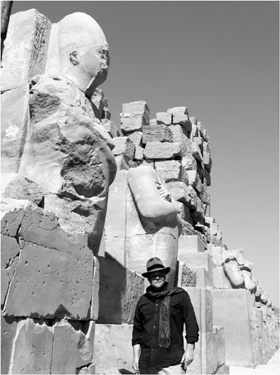

Moses confronts the Pharaoh, who at this time is the son of Thutmoses III, Amenhotep II. It is not clear whether he knows who Moses is (at least the biblical passage says nothing about that), but it is not outside the realm of probability that if he knows anything about Hatshepsut, he also knows of Moses/Senenmut. As a matter of fact, it is he, Amenhotep II, who takes it upon himself to eradicate all the images of both Hatshepsut and Senenmut. Could this be something he does after his encounters with Moses? After the loss of their Hebrew slaves? The timing is right, as Moses returns to Egypt only a year or two after the death of Thutmoses III, and perhaps all the stories of Hatshepsut and Senenmut are still ringing in the ears of Amenhotep II. Perhaps the reappearance of Senenmut as Moses, 40 years later, spurs the young Pharaoh into action against their images on the walls of Karnak and Djeser Djeseru at Deir el Bahri.3

Scotty at Karnak Temple with Amenhotep II, his candidate for Pharaoh of the Exodus.

So, Moses and Aaron have an audience with the Pharaoh, demanding he let the Israelites go free. Amenhotep II of course refuses, and a series of plagues are unleashed on Egypt with each successive plague.

Now, in contrast with John, it is my belief that the entire plague scenario and Exodus took place from the Nile Delta area, and the land of Goshen where the Hebrews lived in a not-too-distant proximity from the northern capitol of Mennfer (Memphis). If the scriptural story bears any sort of linguistic weight, we are told that Moses came to and fro rather freely and rather quickly. If he had to traverse the 400-plus miles between Goshen and Thebes for each successive meeting with Amenhotep II, this process could have taken years. But as it is, the biblical accounting seems to indicate a number of weeks transpired as opposed to months or even years.

The Ten Plagues is one of those stories that so smacks of religious mythology, it gets overlooked in analysis very easily. Some have even tried to maintain that the story is true, but just a situation where Moses relied on natural occurrence rather than divine intervention, but believing that Moses was lucky enough to have a series of strange natural occurrences all happen in a row—as well as some of the explanations concocted to describe these possible natural occurrences—takes more faith to believe than simply adhering to a belief that a Divine Power caused miraculous events to happen out of nothing.

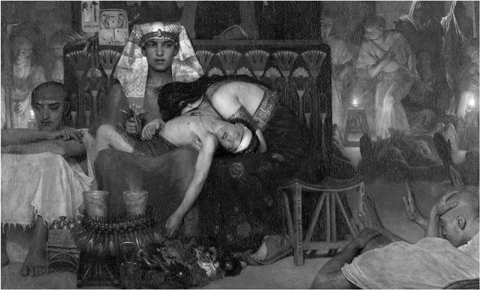

“Every firstborn son in Egypt will die, from the firstborn son of Pharaoh, who sits on the throne, to the firstborn son of the female slave...” Death of the Pharaoh’s Firstborn Son by Lawrence Alma-Tadema, 1872.

The biblical account lists Ten Plagues that befell Egypt as a result of Amenhotep’s refusal to release the Hebrew slaves:

1. Water Turned to Blood (Exodus 7:14–25)

2. Frogs (Exodus 8:1–15)

3. Lice (Exodus 8:16–19)

4. Flies (Exodus 8:30–32)

5. Cattle Disease (Exodus 9:1–7)

7. Hail of Fire (Exodus 9:13–19)

8. Locusts (Exodus 10:1–20)

9. Darkness (Exodus 10:21–29)

10. Death of the Firstborn (Exodus 12:29–33)

There is one odd, little piece of papyrus that has fallen under great scrutiny in regard to its possible linkage to the miraculous events of Exodus, and that is the Ipuwer Papyrus.

This much-disputed artifact is a single papyrus containing an ancient Egyptian poem, called “The Admonitions of Ipuwer”4 or “The Dialogue of Ipuwer and the Lord of All.”5

The papyrus is both unique and under debate because it so closely resembles the events associated with the biblical story of the Ten Plagues—and when anything gets close to looking too biblical, it is going to fall under much more scrutiny. In the story we are told of chaos in Egypt, of the world turning upside down, of warfare, famine, death, and poverty, and of a world where the servants and slaves run free and rebellion ensues.

The date of the poem remains completely unknown, but the one surviving copy that still exists is a copy that dates back to the 13th century BC, no later than the 19th Dynasty. But the poem is thought to be much older.

The papyrus contains some startling similarities to the Exodus account:

Papyrus 2:10—“The river is blood.”

Exodus 7:20—“...all the waters that were in the river were turned to blood.”

Papyrus 4:14, 6:1—“Trees are destroyed. No fruit nor herbs are found.”

Exodus 9:25—“...and the hail smote every herb of the field, and brake every tree of the field.”

Papyrus 2:10—“Forsooth, gates, columns and walls are consumed by fire.”

Exodus 9:23–24—“...the fire ran along the ground....there was hail, and fire mingled with the hail, very grievous.”

Papyrus 9:11—“The land is not light....”

Exodus 10:22—“...and there was a thick darkness in all the land of Egypt.”

Papyrus 4:3, 5:6, 6:12—“Forsooth, the children of princes are dashed against the walls. Forsooth, the children of princes are cast out in the streets.”

Exodus 12:29—“And it came to pass, that at midnight the Lord smote all the firstborn in the land of Egypt, from the firstborn of Pharaoh that sat on his throne unto the firstborn of the captive that was in the dungeon.”

As you can imagine, the Egyptologists and archaeologist had a field day with this papyrus, and the various theories range from the papyrus describing the conditions of the Egyptians while under the northern domination of the Hyksos, to parts of the papyrus thought to be addressing the Pharaoh Khety of the 13th Dynasty, and the admonitions contained therein as addressing the god Atum, not a singular human king.

The likelihood that this particular document is an actual accounting of the plagues that would have befallen Egypt under the reign of Amenhotep II in the year 1446 BC is probably unlikely, and the biblical account is more than likely the only surviving account of what happened, so it has to remain in the realm of “biblical myth” as opposed to verifiable fact.

There is no direct evidence, and scarcely any secondary archaeological evidence for the Ten Plagues as they occurred in the biblical tale. This is one that has to remain in the realm of faith, for the present.

The Ipuwer Papyrus, by the way, has been much vaunted by the UFO community in that they take certain events listed in the document—rings of fire that appear in the sky—and attribute them to their own brand of ufological mythology. So, if you are a believer in scripture and/or a believer in UFO phenomena, this is your document. But there is no evidence that it is anything other than a legendary poem out of antiquity.

There is, however, an interesting theory regarding the pharaoh who presided during the period of the Ten Plagues, and this is put forward in The Secret of Qumran by R.P. BenDedek.6

It is BenDedek’s contention that the pharaoh of the Exodus is not really the pharaoh at all, but the representative of the pharaoh, as in his Grand Vizier who is the Pharaoh pro tempore in his absence. He places the Plagues and the Exodus under the reign of Amenhotep II, but contends that Amenhotep II was away campaigning at war during the time of the Plagues and the release of the Hebrew slaves. And when he returns his wrath falls squarely on the shoulders of his old Grand Vizier, Rekhmire.7, 8

The cornerstone to this theory rests on a literal interpretation of “The Song of Moses and Miriam” found in Exodus 15:1–21. If the individual lines are taken literally, the song tells of how the Pharaoh and his chariots were all buried in the closing walls of the parted Red Sea, and how they all drowned. The problem is that if Amenhotep II is the pharaoh of the Exodus, he lived past the date of the Exodus and ruled for another 29 years.

Shirat HaYam, The Song of the Sea

Also known as, The Song of Moses and Miriam

1 Then Moses and the Israelites sang this song to the Lord:

“I will sing to the Lord, for he is highly exalted. Both horse and driver he has hurled into the sea.

2 “The Lord is my strength and my defense; he has become my salvation. He is my God, and I will praise him, my father’s God, and I will exalt him.

3 The Lord is a warrior; the Lord is his name.

4 Pharaoh’s chariots and his army he has hurled into the sea. The best of Pharaoh’s officers are drowned in the Red Sea.[b]

5 The deep waters have covered them; they sank to the depths like a stone.

6 Your right hand, Lord, was majestic in power. Your right hand, Lord, shattered the enemy.

7 “In the greatness of your majesty you threw down those who opposed you. You unleashed your burning anger; it consumed them like stubble.

8 By the blast of your nostrils the waters piled up. The surging waters stood up like a wall; the deep waters congealed in the heart of the sea.

9 The enemy boasted, ‘I will pursue, I will overtake them. I will divide the spoils; I will gorge myself on them. I will draw my sword and my hand will destroy them.’

10 But you blew with your breath, and the sea covered them. They sank like lead in the mighty waters.

11 Who among the gods is like you, Lord? Who is like you—majestic in holiness, awesome in glory, working wonders?

12 “You stretch out your right hand, and the earth swallows your enemies.

13 In your unfailing love you will lead the people you have redeemed. In your strength you will guide them to your holy dwelling.

14 The nations will hear and tremble; anguish will grip the people of Philistia.

15 The chiefs of Edom will be terrified, the leaders of Moab will be seized with trembling, the people of Canaan will melt away;

16 terror and dread will fall on them. By the power of your arm they will be as still as a stone—until your people pass by, Lord, until the people you bought pass by.

17 You will bring them in and plant them on the mountain of your inheritance—the place, Lord, you made for your dwelling, the sanctuary, Lord, your hands established.

18 “The Lord reigns for ever and ever.”

19 When Pharaoh’s horses, chariots and horsemen went into the sea, the Lord brought the waters of the sea back over them, but the Israelites walked through the sea on dry ground.

20 Then Miriam the prophet, Aaron’s sister, took a timbrel in her hand, and all the women followed her, with timbrels and dancing.

21 Miriam sang to them: “Sing to the Lord, for he is highly exalted. Both horse and driver he has hurled into the sea.”

BenDedek speaks a bit conspiratorially when he suggests that a dating system known as “The King’s Calendar” is really an obfuscated calendar meant to conceal the true history of Israel:

The King’s Calendar position is not that of such people, but rather that the Biblical Records are in fact reliable historical records. They do nevertheless contain errors, and more importantly as the King’s Calendar research demonstrates, contain a chronology that was designed to conceal the exact and true chronological history of Israel. In demonstrating that the Exodus occurred in the 18th Egyptian Dynasty (15th century BCE), the King’s Calendar computer generated mathematical calendar indicates that the Mosaic Exodus occurred in 1449 BCE, with the Israelites crossing over into Canaan in 1412 BCE.

Traditional dating for the 18th Egyptian Dynasty, (although academics have yet to agree with each other), definitely indicates that the Pharaoh of the Exodus was either Thutmoses III or Amenhotep II. The King’s Calendar demonstrates that it was Pharaoh Amenhotep II.

As he did not die in any crossing of the Red Sea (a challenge itself to Biblical Infallibility), some explanation must be found for the Israelite rejoicing at Pharaoh’s demise in the Red Sea. But does the Bible actually say that Pharaoh drowned in the Red Sea?9

The main premise of this theory is that Pharaoh Amenhotep II, out on campaign, leaves Grand Vizier Rekhmire in charge, who has the power to be Pharaoh in Amenhotep’s absence, much like Joseph wielded the power of the Pharaoh when he was the Grand Vizier of Egypt.10 Rekhmire had been the Grand Vizier and in service to the father of Amenhotep—Thutmoses II—for 54 years, and was well-established as a councilor to the pharaohs. Of course Amenhotep, the young, boisterous, egotistical, wrathful Pharaoh that he was know to be, would just as soon clean out the cupboards and build everything new in his own image and under his own hand. So Rekhmire, whether a victim of the close personal wrath of Amenhotep, or as the “Pharaoh” sent by Amenhotep to pursue the fleeing slaves, found a bitter end to his otherwise glorious and lengthy career. His death is a mystery, but it is suspected that he fell out of favor for some disgrace and this precipitated an “unnatural” demise at the hands of Pharaoh Amenhotep II. Perhaps it was the loss of the entire Hebrew slave population that is at the core. According to this theory, Grand Vizier Rekhmire is actually the Pharaoh of the Exodus who was not really the Pharaoh. It seems that Amenhotep II had no idea the Hebrews had left, and had to be informed. A few biblical passages in Exodus 14:5–12 illustrate this point:

5 When the king of Egypt was told that the people had fled, Pharaoh and his officials changed their minds about them and said, “What have we done? We have let the Israelites go and have lost their services!” 6 So he had his chariot made ready and took his army with him. 7 He took six hundred of the best chariots, along with all the other chariots of Egypt, with officers over all of them. 8 The Lord hardened the heart of Pharaoh king of Egypt, so that he pursued the Israelites, who were marching out boldly. 9 The Egyptians—all Pharaoh’s horses and chariots, horsemen[a] and troops—pursued the Israelites and overtook them as they camped by the sea near Pi Hahiroth, opposite Baal Zephon.

10 As Pharaoh approached, the Israelites looked up, and there were the Egyptians, marching after them. They were terrified and cried out to the Lord. 11 They said to Moses, “Was it because there were no graves in Egypt that you brought us to the desert to die? What have you done to us by bringing us out of Egypt? 12 Didn’t we say to you in Egypt, ‘Leave us alone; let us serve the Egyptians’? It would have been better for us to serve the Egyptians than to die in the desert!”

Amenhotep II was also concerned that the Exodus may have been procured by the use of the magick arts, as indicated in Josephus Antiquities 2:15:3.

“But the Egyptians soon repented that the Hebrews were gone; and the king also was mightily concerned that this had been procured by the magic arts of Moses. So they resolved to go after them.”

But also according to Josephus, the Hebrews—nearly 1.2 million in number fleeing Egypt—were pursued by Pharaoh’s army that was “600 chariots, 50,000 horsemen and 250,000 foot soldiers all armed.” So roughly 300,600 soldiers strong was Pharaoh’s army that pursued the escaping Hebrews.

That is quite a horde. And they all supposedly bottlenecked at the Red Sea. It seems to me that these biblical and ancient historical documents have a way with distorting numbers. But that is not to say that the event did not take place.

There is no historical data to lend any archaeological or historical veracity to this biblical account, other than the pages of scripture itself. What we do know is that the Hebrews did not cross at the wide expanse of the Red Sea, but rather at a place referred to as the yam suph, most probably identified with the Lake Timsah region, a few miles to the north end of the Red Sea. A mistranslation in the Septuagint renders yam suph as the Red Sea, when in reality it says the Reed Sea or Sea of Reeds.11 This is a region just north of the Red Sea where the waters flow into salt lakes, but it is very shallow and could actually be crossed on foot.

If you are open to miracles, then anything is possible. The Hebrews would have come to the lake or to the larger expanse of the Red Sea and God would have parted the waters and closed them up on the pursuing Egyptian army of 300,600 soldiers, because the passage says they all were drowned in the closing of the sea.

However, there are other possibilities, in that the Sea of Reeds was passable by foot, and it has been an observable event that sometimes in the spring and summer, strong winds can dry portions of the shallow lake, and you walk across on the dried-out bottom of the lake. The biblical passage tells us that Moses stretched his staff over the waters and that a strong east wind blew all night and parted the waters. Read this dramatic passage from Exodus 14:10–31:

10 As Pharaoh approached, the Israelites looked up, and there were the Egyptians, marching after them. They were terrified and cried out to the Lord. 11 They said to Moses, “Was it because there were no graves in Egypt that you brought us to the desert to die? What have you done to us by bringing us out of Egypt? 12 Didn’t we say to you in Egypt, ‘Leave us alone; let us serve the Egyptians’? It would have been better for us to serve the Egyptians than to die in the desert!”

13 Moses answered the people, “Do not be afraid. Stand firm and you will see the deliverance the Lord will bring you today. The Egyptians you see today you will never see again. 14 The Lord will fight for you; you need only to be still.”

15 Then the Lord said to Moses, “Why are you crying out to me? Tell the Israelites to move on. 16 Raise your staff and stretch out your hand over the sea to divide the water so that the Israelites can go through the sea on dry ground. 17 I will harden the hearts of the Egyptians so that they will go in after them. And I will gain glory through Pharaoh and all his army, through his chariots and his horsemen. 18 The Egyptians will know that I am the Lord when I gain glory through Pharaoh, his chariots and his horsemen.”

19 Then the angel of God, who had been traveling in front of Israel’s army, withdrew and went behind them. The pillar of cloud also moved from in front and stood behind them, 20 coming between the armies of Egypt and Israel. Throughout the night the cloud brought darkness to the one side and light to the other side; so neither went near the other all night long.

21 Then Moses stretched out his hand over the sea, and all that night the Lord drove the sea back with a strong east wind and turned it into dry land. The waters were divided, 22 and the Israelites went through the sea on dry ground, with a wall of water on their right and on their left.

23 The Egyptians pursued them, and all Pharaoh’s horses and chariots and horsemen followed them into the sea. 24 During the last watch of the night the Lord looked down from the pillar of fire and cloud at the Egyptian army and threw it into confusion. 25 He jammed the wheels of their chariots so that they had difficulty driving. And the Egyptians said, “Let’s get away from the Israelites! The Lord is fighting for them against Egypt.”

26 Then the Lord said to Moses, “Stretch out your hand over the sea so that the waters may flow back over the Egyptians and their chariots and horsemen.” 27 Moses stretched out his hand over the sea, and at daybreak the sea went back to its place. The Egyptians were fleeing toward it, and the Lord swept them into the sea. 28 The water flowed back and covered the chariots and horsemen—the entire army of Pharaoh that had followed the Israelites into the sea. Not one of them survived.

29 But the Israelites went through the sea on dry ground, with a wall of water on their right and on their left. 30 That day the Lord saved Israel from the hands of the Egyptians, and Israel saw the Egyptians lying dead on the shore. 31 And when the Israelites saw the mighty hand of the Lord displayed against the Egyptians, the people feared the Lord and put their trust in him and in Moses his servant.

Our ultimate goal here is to attempt to find plausible historical evidence for these events. When we are in the palaces of Egypt, this is much easier, as we can focus on people and places. But when you get to deciphering things that are miraculous events that might be able to be explained by natural occurrences, you might end up with plausibility, but what does that do to the faith element of the tale?

To suggest that 1.2 million fleeing slaves plus another 300,600 Egyptian soldiers with 600 chariots and 50,000 horses all entered the Sea of Reeds in one single night, you are stretching not only the bounds of the imagination, but also the limits of physics.

After the successful crossing of the Sea of Reeds, the Hebrews head south to avoid the Philistines to the north. The easiest passage would be to turn north and walk across the northern Negev, right into what is southern Israel today. But instead, they turn south and march down the eastern shore of the Red Sea. Of course, it has been established that there existed at this time a line of Egyptian forts along the Negev at the north of the Sinai peninsula. Turning north would have run the Hebrews directly into several defensive stations of the Egyptian army who were probably already on the alert for them. So the Hebrews turn south and veer inland at what is now the approximate area of the seaside town of Abu Zenima, and travel about 25 miles to a mountain known as Serabit el Khadim. Atop this mountain lay the ruins of the Temple Sanctuary of Hathor, the cow goddess of Egypt, bringer of joy and motherly love.

Sir Flinders Petrie was a British Egyptologist and pioneer of systematic methodology in archaeology and the preservation of historical artifacts. He was also the first chair of Egyptology in Great Britain, and personally excavated and catalogued many of the most important archaeological sites in Egypt. It was his contention that Serabit el Khadim was the Holy Mountain of God mentioned throughout the biblical Exodus account. But he encountered resistance when he suggested that Moses went there to visit the priests who lived there rather than encounter the presence of God. So Serabit el Khadim was scratched off the list as a candidate for the biblical Mt. Sinai by many late-19th- and early-20th-century archaeologists and historians.

The long escarpment atop Serabit el Khadim, where the processional route would lead to the outer gate of the Temple of Hathor seen in the distance.

As I began to account at the beginning of this chapter, John and I climbed to the top of Serabit el Khadim and we walked the escarpment surrounded by the haze of Sinatic mountain peeks all around us. The sun was shining but there was the continual rising mist of dust and blowing sand that cast the entire mountaintop in filtered light, even at midday. The place had a calm, almost melancholic enchantment with a decidedly ethereal feel. Above all else it was incredibly quiet as we cleared a small hillock and saw the ruins of Hathor’s Temple at the far end of the escarpment. The ruins were magnificent in their decay. Obvious signs of earthquake were all around the debris. The mountain was obviously not always this quiet.

Though John and I bring differing views of who Moses was and when the events of the Exodus took place, we both agree that lonely, desolate, remote mountaintop was the place where Moses climbed to visit the priests of Hathor, and ritually cleansed himself as he had done here at other times in his former life as a Prince of Egypt. It was here on this mountaintop that he carved the small stele of the tablets of the Law and carried them back down to the waiting horde of Hebrews camped in the basin and wadis below, who had built a representation of the god who had just a week earlier delivered them from the hands of the Egyptian soldiers—Hathor, the Egyptian god of joy, feminine love, and motherhood. Here in this mountainous region of the Sinai desert wilderness, surrounded by copper and turquoise mines, she was also known as Patron God of Miners.

Moses was apoplectic when he learned that the people who he had just led out of Egypt in the name of Yahweh, the new god who revealed himself to Moses through the fires of the burning bush that was not consumed, were so soon reverted back to their Egyptian ways and their Egyptian understanding of God. As a result, Moses dealt with them harshly in Exodus 32:15–35.

15 Moses turned and went down the mountain with the two tablets of the covenant law in his hands. They were inscribed on both sides, front and back. 16 The tablets were the work of God; the writing was the writing of God, engraved on the tablets.

17 When Joshua heard the noise of the people shouting, he said to Moses, “There is the sound of war in the camp.”

18 Moses replied:

“It is not the sound of victory,

it is not the sound of defeat;

it is the sound of singing that I hear.”

19 When Moses approached the camp and saw the calf and the dancing, his anger burned and he threw the tablets out of his hands, breaking them to pieces at the foot of the mountain. 20 And he took the calf the people had made and burned it in the fire; then he ground it to powder, scattered it on the water and made the Israelites drink it.

21 He said to Aaron, “What did these people do to you, that you led them into such great sin?”

22 “Do not be angry, my lord,” Aaron answered. “You know how prone these people are to evil. 23 They said to me, ‘Make us gods who will go before us. As for this fellow Moses who brought us up out of Egypt, we don’t know what has happened to him.’ 24 So I told them, ‘Whoever has any gold jewelry, take it off.’ Then they gave me the gold, and I threw it into the fire, and out came this calf!”

25 Moses saw that the people were running wild and that Aaron had let them get out of control and so become a laughingstock to their enemies. 26 So he stood at the entrance to the camp and said, “Whoever is for the Lord, come to me.” And all the Levites rallied to him.

27 Then he said to them, “This is what the Lord, the God of Israel, says: ‘Each man strap a sword to his side. Go back and forth through the camp from one end to the other, each killing his brother and friend and neighbor.’” 28 The Levites did as Moses commanded, and that day about three thousand of the people died. 29 Then Moses said, “You have been set apart to the Lord today, for you were against your own sons and brothers, and he has blessed you this day.”

30 The next day Moses said to the people, “You have committed a great sin. But now I will go up to the Lord; perhaps I can make atonement for your sin.”

31 So Moses went back to the Lord and said, “Oh, what a great sin these people have committed! They have made themselves gods of gold. 32 But now, please forgive their sin—but if not, then blot me out of the book you have written.”

33 The Lord replied to Moses, “Whoever has sinned against me I will blot out of my book. 34 Now go, lead the people to the place I spoke of, and my angel will go before you. However, when the time comes for me to punish, I will punish them for their sin.”

35 And the Lord struck the people with a plague because of what they did with the calf Aaron had made.

And this is the cyclical story that continues to repeat and repeat and repeat all through the next 40 years as the Hebrews wander the desert wilderness of the Sinai. And it is not until the entire generation dies off that they are allowed to enter the Land of Promise.

I have often wondered how a Semitic slave people, whom we have learned through our various synagogue and church teachings were a people of God, could so soon and so quickly turn to idol worship after having experienced such wondrous acts of their God. They saw the devastation that the Plagues took on the Egyptians—yet not on them. They slathered and swiped their doorposts and lintels with sheep’s blood to stave off the Plague against the first born, and they saw miraculous deliverance. They found themselves trapped up against the waters of the sea, with Pharaoh’s armies closing down on them, yet were once again delivered by the miraculous hand of the Divine who sent a cloudy pillar of fog and fire, and the opened the waters of the sea so they could cross on dry ground. They experienced the wonders of their God, right before their very eyes! And yet, just a few short weeks later, while Moses was at the top of the mountain, they needed a physical representation of that God, saying, “We don’t know what’s happened to this man, Moses, who led us out of Egypt. Where did he go?” And Aaron, Moses’ brother, told them to turn over all the gold they had plundered from the Egyptians and he cast a Golden Calf, and sculpted it with engravers’ tools. The people all responded, “These are your gods, O Israel, who brought you up from Egypt!”

How could they so readily abandon this god of Moses? The answer is that, perhaps, they didn’t. They were simply a product of their environment. They were not a people of Jehovah, they were the descendants of a Canaanite family that had, throughout the past 400 years, been thoroughly assimilated into Egyptian culture. Even as slaves, they were completely “Egyptianized.” And the building of the Golden Calf is simply a clue as to who these people really were, and how Egyptian they had become as a people group.

Perhaps Moses/Senenmut was a man bent on nation-building. He had fled Egypt 40 years earlier, the facts of which are lost in antiquity, save for the account in the biblical passages—and we already know how those texts can lose historical reliability in light of their editing and faith-based presentation. Again, this is not to say that the biblical passages are false or manufactured, but they have obviously shown us that a keen eye to the historical details was deemed as unnecessary to their overall theme of bolstering the faithful and building a history for the nation of Israel. Perhaps Moses did indeed murder an Egyptian taskmaster, precipitating his flight from the “wrath of the Pharaoh” who sought to take his life. But as mentioned earlier, there is probably much more to this scenario than the biblical account mentions. Senenmut, Royal Architect under Pharaoh Hatshepsut, most certainly had continual contact with the builders, workers, overseers, and task masters associated with his projects. Was there some devastatingly heinous encounter he had with one of the overseers? Was this something that launched a political move from Thutmoses III? Could this be the source of Senenmut’s disappearance from Egyptian history?

And only after 40 years hiding in the Sinatic wilderness, did Senenmut return, when his old rival, Thutmoses III, had died and left his son, Amenhotep II on the throne? And perhaps this very act of Senenmut’s return and the Great Exodus was the very sparking point of Amehotep’s ragefull eradication of not only Hatshepsut, but her Grand Vizier, Hereditary Crown Prince Senenmut, from the walls of Egypt’s temples and monuments.