2

THUNDRING NOYSE

THE ENGLISH KING Edward III, a bold 34-year-old overreacher, traveled to the Continent in the summer of 1346 and mounted a campaign to enforce his claim to the throne of France. He landed on a Normandy beach and inflicted on the French countryside a form of violence known as “havoc”—murder, plunder, rape, war on the cheap. He burned towns within sight of Paris, alarming its citizens.

With his flowing blond hair and beard, his athletic physique, his devotion to pomp and pageantry, his love for the brutal spectacle of jousting, Edward embodied the age of chivalry. He hoped to make the mythical Camelot a reality, to preside over a Round Table as splendid as that of King Arthur. Yet his idealism and nostalgia never clouded his cold-eyed perception of war’s realities. The king had brought with him a new technology that was all the rage across Europe: gunpowder. Though he could hardly have imagined it at the time, this was the very weapon that would one day wipe away the customs of feudal knighthood that he held so dear.

War in the Middle Ages relied on man’s muscles. A battle tested strength against strength—every warrior’s pride was his ability to fight. Edge weapons like swords and spears concentrated muscular energy. Catapults and siege engines accumulated and stored human strength. The crux of battle was the melee, a free-for-all among men-at-arms. The sword, the extension of the arm, was the icon of war. Gunpowder would introduce a new dimension, one independent of human strength.

Gunpowder had been known in Europe for several decades by Edward’s day, but had yet to find a solid place in the warrior’s catalogue of arms. Embraced by brutal enthusiasts like Edward, it would, during the fourteenth century, begin to widen the scope of men’s ability to inflict violence. It would force commanders to rethink military axioms that had stood for centuries and extend the reach and destructive capability of individual soldiers, setting off ripples that would be felt across Europe and around the world.

ONE THING IS certain: Europeans knew of gunpowder by the middle of the thirteenth century; how the technology reached the West has long been subject to dispute. In 1854 an historian asserted authoritatively that the Egyptians had used gunpowder and that Moses had known of it. A leading twentieth-century English expert on artillery listed seventeen arguments to show that “there is no trustworthy evidence to prove that the Chinese invented gunpowder.” Instead, he maintained, they borrowed it from the West.

Three pieces of evidence have convinced scholars that Europe’s knowledge of gunpowder originated in China. The first is precedence. The Chinese had some notion as early as the ninth century that saltpeter, sulfur, and carbon could burn with unprecedented vigor. By 1044 they had recorded formulas for gunpowder. The earliest reference to gunpowder in Europe is from 1267, the first formulas emerged around 1300, the first military use was noted in 1331. There is no evidence of gunpowder nor of any progress toward it in Europe until it had long been known in China.

The second persuasive indicator is gunpowder’s lengthy evolution in China, including centuries of improvements in the refining of saltpeter, elixirs that flared up unexpectedly, and gunpowder formulations too weak to be explosive. This suggests that alchemists and military engineers proceeded slowly toward true gunpowder, then gradually strengthened it. No parallel development is evident in European records. Gunpowder appeared suddenly in Europe, and a little more than half a century later gunners were firing cannon at the walls of castles. This accelerated development indicates that Europeans borrowed a technology that had already been fully worked out in the East. No groping was necessary.

The third piece of evidence, minor but telling, is that early European gunpowder recipes included poisons like sal ammoniac and arsenic, the same ones that the Chinese used. These ingredients did nothing to improve the powder. Their presence in the formulas of both cultures is an unlikely coincidence and suggests that Europeans received the idea directly from China.

The route of this transfer and the exact date that gunpowder arrived in the West are not known and may never be known. Speculation has pointed in several directions. The Mongols were expanding across the entire Eurasian mainland in the thirteenth century. They swept through Persia and captured Baghdad in 1256. While they relied principally on their ferocious cavalry techniques, the Mongols brought Chinese engineers to western Asia and may have used gunpowder weapons against the Arabs. It’s possible that they transferred to Europeans the secrets of the explosive.

Direct contacts between China and Europe, though still limited, were increasing at the same time that knowledge of gunpowder was spreading. Friars visited the Mongol court as early as the 1230s. Merchants and adventurers were also drawn East—Marco Polo did not return from the court of Kublai Khan until 1292, after gunpowder had already arrived, but other Italian merchants had journeyed to the Orient at midcentury.

Speculation has looked to an incendiary weapon known as Greek Fire as a possible precursor of gunpowder. This fiercely burning substance was invented in Byzantium around A.D. 675 by a Jewish architect and Syrian refugee named Kallinikos. Its formula was a closely guarded secret that remains a mystery to this day. Kallinikos most likely distilled petroleum into something like gasoline, which he thickened with resin to create a primitive form of napalm. It’s possible that the incendiary contained saltpeter, which added to the intensity of its burning. In that case, gunpowder could trace a line of descent back to the Greek invention. Definitive evidence is lacking.

It’s likely that the Arabs played some role in the transmission of gunpowder to the West. In the thirteenth century, the followers of Islam had established a cosmopolitan culture stretching from the Iberian peninsula to India with technical achievements surpassing anything in Christendom. Around 1240 the Arabs acquired knowledge of saltpeter (“Chinese snow”) from the East, perhaps through India. They knew of gunpowder soon afterward. They also learned about fireworks (“Chinese flowers”) and rockets (“Chinese arrows”).

Arab warriors had acquired fire lances by 1280. Around that same year, a Syrian named Hasan al-Rammah wrote a book that, as he put it, “treats of machines of fire to be used for amusement or for useful purposes.” He talked of rockets, fireworks, fire lances, and other incendiaries, using terms that suggested he derived his knowledge from Chinese sources. He gave instructions for the purification of saltpeter and recipes for making different types of gunpowder.

The oldest written recipes for gunpowder in Europe were recorded under the name Marcus Graecus or Mark the Greek. The attribution did not refer to an individual but to the editors who over two centuries compiled and emended a how-to manual entitled Book of Fires for the Burning of Enemies. The short work, written in Latin, very likely has Arabic roots—it may have been translated by scholars in Spain. “Fire flying in the air is made from saltpeter and sulfur and vine or willow charcoal,” it states, giving proportions that amount to 69 percent saltpeter, which would have formed a relatively strong and explosive powder. The part of the manuscript dealing with the remarkable powder is a late addition, added between 1280 and 1300.

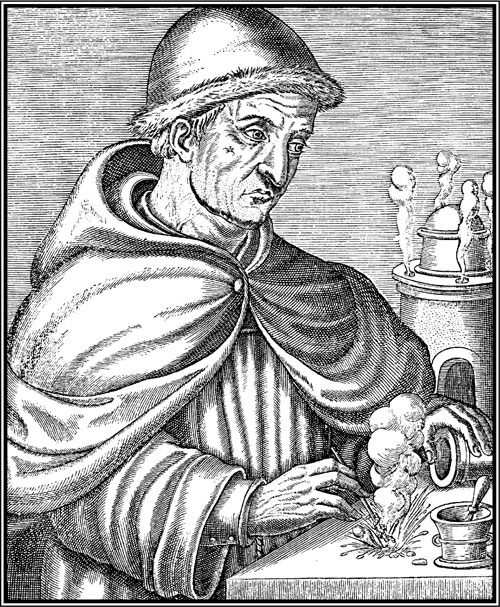

The introduction of gunpowder into Europe has traditionally been associated with two men. The first was Berthold Schwartz, known as Black Berthold or der Schwartzer, perhaps because of his complexion, perhaps to signify his interest in the dark arts. Some said he was a Dane or a Greek; most agreed he was a German; all were sure he was a monk. According to accounts from the fifteenth century, Berthold was an alchemist who heated sulfur and saltpeter in a pot until it exploded. He tried the same experiment using a closed metal vessel and it blew his laboratory apart. “The best approved authors agree that guns were invented in Germanie, by Berthold Swarte,” an historian declared in 1605. The German city of Freiburg claimed Berthold as a native son and town fathers erected a statue of the great inventor.

The catch is that Berthold never existed—he was a legendary figure, like Robin Hood. The myth of his life served to bolster the Germans’ claim of having invented the gun. The story also shielded Europeans from the fact that gunpowder, a critical force in their history, had emerged not from their own inventiveness but from the ingenuity of the Oriental mind. In fact, Berthold was an archetype, a stand-in for all the curious and ingenious experimenters willing to risk life and limb to explore and profit from the astounding new mixture.

The other seminal gunpowder figure is Roger Bacon, a real person and one of the most daring intellects of his age. Born around 1214, Bacon came from a wealthy English family and pursued an academic career at Oxford, then lectured at the University of Paris. In 1247, Bacon became intensely interested in the physical world and began to examine natural phenomena in detail. He spent enormous sums on experiments in fields like optics and astronomy, attempting to build on the newly available theories of Aristotle. Often ornery and dogmatic, he crudely criticized other scholars. After becoming a Franciscan friar, he corresponded with Pope Clement IV, for whom he wrote three great works that were intended to sum up all human knowledge about the natural universe.

A late sixteenth-century depiction of the mythical Berthold Schwartz.

The story has long circulated that Bacon left behind a formula for gunpowder. It’s said that he recognized the danger of the invention and so recorded the information only as an anagram, a code that remained unbroken for centuries. This is the stuff of legend and that’s exactly what it turns out to be. The letter containing the alleged formula cannot be definitely attributed to Bacon, and the coded “formula” is open to any number of interpretations.

Bacon does hold the distinction of having set down the first written reference to gunpowder in Europe. It came in the works he prepared for the Pope around 1267—and which Clement died without reading. Bacon wrote of “a child’s toy of sound and fire made in various parts of the world with powder of saltpetre, sulphur and charcoal of hazelwood.” The effect of the device was quite astounding to the medieval mind. “By the flash and combustion of fires,” Bacon wrote, “and by the horror of the sounds, wonders can be wrought and at any distance that we wish—so that a man can hardly protect himself or endure it.”

The potential danger of this new form of energy did not escape him. Since a tiny firecracker “can make such a noise that it seriously distresses the ears of men . . . if an instrument of large size were used, no one could stand the terror of the noise and flash. If the instrument were made of solid material, the violence of the explosion would be greater.” It was a prophetic insight.

EIGHT DECADES later, in the French hinterland north of Paris, an English king was about to put to use the violent explosions that Bacon had foreseen. Edward’s 1,200 men-at-arms and 8,000 longbowmen had been standing all day in the August heat. Many had encased themselves in garments of chain mail and plate steel. They gripped the smooth-worn handles of swords, knives, bludgeons. They waited in a field about twenty miles from the Channel coast—the nearby village of Crécy would give the coming battle its name.

The sky suddenly darkened, thunder rolled across the countryside. A crash startled a flock of crows and sent them wheeling over the sloping field just before a downpour. Anyone seeking a portent could have found it in the flight of black birds. Few persons alive in 1346 took such omens lightly. Death was in the air. Indeed, death was gathering a few hundred yards away: The French king Philip VI was massing thousands of trained killers astride warhorses at the far end of the field. A line of Genoese crossbowmen were preparing weapons that could drive a bolt through a sheet of steel. The sun, slipping from behind a thunderhead, made the polished armor glitter and lit up the elaborate plumes and multicolored banners of the gathering warriors.

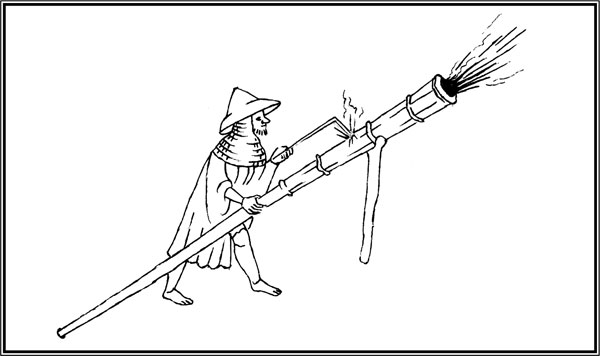

Soldier firing a fifteenth-century hand cannon

The foreboding of the English soldiers must have mixed with a sense of expectation as they waited for the debut of their unprecedented weaponry. The guns at Crécy were small cast bronze or iron tubes strapped to wooden frames. Perhaps they were “ribaudequins,” collections of small guns arranged on a wheelbarrowlike cart that could fire a salvo. Edward did not assign them to soldiers. He needed specialists, men who understood this novel form of energy. Canny and daring, these gunners knew that the soldiers they accompanied looked on them with jaundiced eye. Hatred of innovation was a military reflex. Gunpowder, closely associated with the necromancy of alchemists, was dangerous, unreliable, and perhaps unlucky.

The gunners took hasty precautions at the approach of the thunderstorm to make sure the rain did not dampen their loaded weapons or their supply of “poudre.” As they waited they experienced the gut-churning anxiety that precedes any battle, the more so because they could see that Edward’s army was seriously outnumbered, menaced by the finest heavy cavalry in Europe. They knew that while a noble man-at-arms might be captured for ransom, a gunner or archer was sure to be hacked to death if the battle went against the English.

Though his imagination had been caught by the mystery of gunpowder, Edward remained a sober and skillful tactician. His principal means of contending with the French was an arm that had been thoroughly tested in battle: the longbow. Trained to the weapon from childhood, Edward’s archers were men of tremendous strength and highly specialized skill. Their skeletons today show the signs of the overdeveloped muscles needed to draw a six-foot-long bow to more than 100 pounds of tension, hold it steady, let loose an arrow, repeat the process again and again, ten times a minute. They could hit targets up to 200 yards distant, their arrows slicing through chain mail and even light plate armor. Edward had forbidden all sport except archery in his kingdom; he could form up enough of these skilled bowmen to deliver a withering storm of projectiles.

To the aristocratic continental warrior, archers were cowards, attacking from a distance with their missiles rather than embracing the face-to-face combat that had been an emblem of military honor since the days of the Teutonic tribes. What was worse, they were commoners. The elites of Europe based their ascendency on military prowess, on their extravagantly expensive mounts, suits of armor, and fortified castles. To them, the notion of a plebeian slaying a gentleman was repugnant. It was an attitude they would apply with even more vehemence to those who wielded gunpowder weapons.

Horses could be heard neighing in the distance. The knights screamed insults back and forth. On the French side, the warriors were bragging about which English noblemen they planned to capture—their opponents’ reputations were well known from the international tournaments. King Edward himself would have been the ultimate prize, followed by his sixteen-year-old son Edward, known as the Black Prince from the color of his jousting armor, who was now preparing to lead a unit of the army in his first great test.

As the sun drifted down behind the English line, Philip hesitated. The 53-year-old monarch was thrown nearly into apoplexy by the sight of this swaggering pretender. Yet Philip’s army had barely formed, the Genoese were fatigued from forced marching. He had not had time to set down a clear plan of attack. Disorder reigned.

Philip’s chevaliers would not be stayed. With evening approaching, fearful that the English would escape his clutches in the dark, he gave the order: Attack.

TO MOST OF the men gathered at Crécy, to all men only two generations earlier, the guns that Edward brought to the battle were inconceivable, elements of pure fantasy. It simply defied the imagination to propose that by no other action than the touch of a hot poker a man could blast a ball from the mouth of a tube and hurl it hundreds of yards at blinding speed. Anyone making such a claim would have been labeled a charlatan, a madman, or a sorcerer. Impossible. Nowhere in their writings had the ancients mentioned such a thing; nowhere in his fables and epics had man dreamed it.

Edward’s new weapons were both the simplest tools ever invented and the most technically advanced products of the age. Like the proliferating array of guns that would appear throughout history, they consisted of little more than a tube sealed at one end, like a reed, or canna in Latin, “cannon.” Edward’s gunners placed their powder at the closed end, where a narrow hole let them introduce ignition. They deposited the projectile closer to the open end. At first they had fired an iron arrow or bolt, later they shot a lead or iron ball, or sometimes a stone chiseled into a sphere. The challenge of early guns came when the thrust of a red-hot rod down the touchhole set off the powder inside.

The explosion of the charge threw the same devastating pressure wave against the sides and rear of the tube as it did against the projectile itself, threatening to blow the gun to pieces. In essence, a gun was a bomb brought under control. The only material that could withstand the unheard-of stress and heat was metal. In the fourteenth century, metal remained a rare, expensive, and intractable material. Gunners were all too aware that a weakness at the breech (the solid base at the bottom of the bore), or an overload of powder, or a ball that jammed in the tube, could raise the pressure inside the gun beyond the bursting point, setting off an explosion that would spray the gunner himself with fire and jagged metal fragments. For the time being, the limits of metallurgy and scarcity of powder kept the guns small.

By the time Edward III mounted the throne, guns were becoming popular in diverse locations around Europe. The Italians, privy to trends in technology through their extensive trading contacts, adopted gunpowder during the years after 1300. The Signoria of Florence ordered city officials in February 1326 to obtain canones de mettallo and a supply of ammunition for the town’s defense. That same year an English Chancery clerk named Walter of Milemete included the earliest known European picture of a gun in a fawning treatise he called “Of the Majesty, Wisdom and Prudence of Kings.” The illumination, which is not discussed in the text, shows a vase-shaped container on a wooden trestle, a large arrow protruding, an armored man gingerly lighting the touchhole.

The new weapon became increasingly widespread during the 1330s. By the following decade most of the arsenals across Europe, from London to Rouen to Siena, listed some form of gunpowder weaponry. The guns were fired mostly in defense of town walls, but a reference from 1331 describes an attack mounted by two Germanic knights on Cividale, a town in the Friuli hills north of Trieste, using gunpowder weapons of some sort.

A French raiding party sacked and burned Southampton on the English coast in 1338, bringing with them a ribaudequin and forty-eight bolts. Since their supplies included only three pounds of gunpowder, they must have been more interested in showing off their new armament than in doing any serious damage.

Edward III joined this trend with enthusiasm. The London Guildhall boasted half a dozen brass “gonnes,” along with powder and lead shot in 1339. Two years before Crécy, the king lured Peter van Vullaere, formerly master of ribaudequins at Bruges, to cross the Channel and supervise the preparation of English gunpowder weaponry. He hired several “artillers” and “gonners,” to assist him. Among the supplies he sent to France to further his raids were 912 pounds of saltpeter and 846 pounds of sulfur for making gunpowder. Van Vullaere may have overseen the guns at Crécy.

A great deal was riding on Edward’s innovative weaponry. A defeat could result in the capture or death of the monarch, radically altering the fortunes of the nation. With the Black Prince also on the field, the French could erase an entire dynasty with a stroke. Thousands of Genoese mercenaries were now advancing up the slope. Their role was to come within striking distance, a hundred yards or so, and let loose their bolts into the English ranks to soften them up for the impending charge of the French knights. The fate of a kingdom rested on the outcome.

WAR IS A psychological drama as well as a physical contest. The goal of battle is to shock, to shatter the cohesion of groups, to bring individual soldiers up short, to instill fear, sow confusion, undermine morale, sap will. Violence is one means of doing so. Intimidation—through a display of power or a loud noise—is another.

Sound was always an accessory of war—drums, trumpets, bagpipes. Shouting was universal. The crossbowmen at Crécy raised three resounding shouts as they advanced within shooting range. The English met each of these bellows with silence. They simply waited.

We don’t know exactly when Edward chose to fire his guns. One account relates that the English “struck terror into the French Army with five or six pieces of cannon, it being the first time they had seen such thundering machines.” Another states that they fired “to frighten the Genoese.” A third says they “shot forth iron bullets by means of fire. They made a sound like thunder.” The thunder that met the attackers made their bellicose shouts seem feeble by comparison.

Astound. Astonish. Stun. Detonate. All of these words derive from a root meaning thunder. On firing, Edward’s guns shot out great tongues of flame followed by roiling clouds of white smoke, an impressive and unique sight to the French knights and their allies. More astounding, more stunning, was the powerful sound of the detonations. If, as one chronicler noted, it scared the horses, it most certainly startled the men as well. It was thunder brought to earth, sound hurled forth as a weapon. Like the crash of thunder from a nearby lightning strike, cannon fire from close range is heard not just with the ears but with the gut, the bones, the nerves. It is feeling more than sound, a sudden expansion of air that delivers a physical blow.

Writers who described early guns almost invariably compared their sound to that of thunder. “As Nature hath long time had her Thunder and Lightning so Art hath now hers,” one observer noted. Shakespeare called them “mortal engines, whose rude throats th’immortal Joves’ dread clamours counterfeit.” Early names for guns referred to their booming sound. In Italian they were schioppi, or “thunderers.” The Dutch had their donrebusse, “thunder gun,” in the 1350s. In English this became the blunderbuss.

The term “gun” had a different origin. The word most likely derived from the Norse woman’s name “Gunnildr,” familiarly shortened to “Gunna.” “Gonne” first shows up in a 1339 document written in Latin. Geoffrey Chaucer, who served in Edward III’s royal administration, initiated the vernacular use of the word in 1384:

As swifte as pelet out of gonne

- When fire is in the poudre ronne.

EARLY GUNPOWDER was weak, and the light guns were unreliable and inefficient—they could shoot only small bits of metal and their accuracy was atrocious. Reloading was cumbersome and time-consuming. All of these factors made the effect of their missiles almost inconsequential. The guns at Crécy struck few men from their horses.

So what led rulers like Edward III to invest scarce resources in the manufacture of guns and the grinding of powder? What induced them to pursue the new technology with such unquenchable enthusiasm? Surely guns possessed a mystique that went far beyond their military effectiveness.

Their diabolical associations were potent. A reputation as a friend of the devil was a valuable asset on the battlefield. The men at Crécy believed wholeheartedly in all the lurid imagery of Christian metaphysics. Hell was a real place, choked by burning brimstone. Demons strode the earth. The guns’ sulfurous exhalations, hideous roars, and stark flashes of light were all trademarks of Satan.

In the secular realm, gunpowder weapons were power made manifest. The man who could field guns, like he who rode the most expensive horse, was a man to be reckoned with. The accouterments of war carried their own prestige, and the medieval mind was deeply taken by regalia. Gunpowder added to the dramatic elements of battle—first as a minor stage effect, later as a dominant theme.

So Edward, in spite of debts that had already bankrupted him, purchased his guns and his powder. Battles, of course, are ultimately won not by show but by violence. Edward’s use of well-positioned archers and armored men fighting afoot from a strong defensive position proved insightful. If the guns gave the Genoese a serious start, the hail of arrows from the English longbows sliced into their ranks with devastating effect. The whizzing arrows cut into horseflesh and occasionally found a gap in a knight’s armor. The disciplined English line withstood repeated attacks. In charge after charge, the standard-bearers of French chivalry were butchered. Philip barely escaped the field with his life. As darkness descended, his Bohemian ally, King John the Blind, was led into the fray by companions—he wanted to die fighting. He did.

THE GUNPOWDER that Edward brought to the field at Crécy was a precious and poorly understood commodity. The men who assembled its materials were the brothers of bakers and brewers: They devised their methods through intuition and knew that minor variations in procedures could significantly alter the outcome. The craft attracted adherents across Europe: alchemists, blacksmiths, enterprising peasants, men fascinated by the unknown or intrigued by the commercial potential, daredevils, visionaries, madmen. Some found in the profession not fortune but disfiguring burns and death—the grinding of gunpowder was ever a perilous craft.

Sulfur, familiar from Biblical times, was the simplest ingredient, easily purified and ground to a fine powder. Charcoal, long used for cooking and metal work, was also easy to obtain. The species of the tree from which it was made mattered most. Charcoal for gunpowder needed both a delicate structure that made it easy to pulverize and a minimum of ash content. Willow was a common source. Alder, chinaberry, and hazelwood also worked, as did grape vines. Old linen sheets heated in a closed vessel were used. In China, adding charred grasshoppers was believed to give powder liveliness.

In Europe, the difficulty of collecting saltpeter long remained a bottleneck in gunpowder production. The continent lacked the hot climate that encouraged rapid decomposition and the extended dry period that allowed nitrates to leach to the surface. Gunpowder fabricators had to seek out saltpeter wherever they could find it.

Medieval Europe was much more rank than our sterilized twenty-first century. Peasants—the vast majority of the population—shared dirt-floor hovels with farm animals. Food scraps and dog shit were ground into the reeds that served as carpeting. Night soil and manure were the only fertilizers, open sewers the norm in towns. It was from this stinking fundament of the human environment that gunpowder makers derived their most precious ingredient.

Observers saw sal petrae, “salt of stones,” forming in white crusts on stone walls. An early monk described it as a “wonder salt” with an infernal spirit concealed in icelike crystals. A writer in 1556 said that saltpeter could be “made from a dry, slightly fatty earth, which, if it be retained for a while in the mouth, has an acrid and salty taste.” Saltpeter had long been used as a preservative to help meat retain its redness. Physicians prescribed it for ailments like asthma and arthritis. In fact, it can be toxic in large quantities, causing anemia, headache, and kidney damage. It was at times touted as an aphrodisiac, though persistent rumors have also insisted that the overseers of army barracks and boys’ schools snuck it into the food to quell the carnal appetites of their charges.

The salt formed on the walls and floors of privies and stables, and in “Vaults, Tombs, or desolate caves, where rain can not come in.” But the natural supply was meager. Every kingdom was hard pressed to produce enough of the crucial substance. Powdermen scoured the land looking for old manure piles and cesspools, middens, and pissoirs. Collectors armed with royal warrants scraped saltpeter from barnyards and dovecotes. Their intrusions annoyed residents who, having seen their yards dug up and structures demolished, were required to provide lodging for the petermen and fuel for boiling down the smelly liquid leached from the ordure.

In 1670 a gentleman named Henry Stubbes mentioned a cave in the Apennine “in which Millions of Owles did lodge themselves, their dung had been accumulating there for many centuries of years.” Mining the guano for its saltpeter produced an “inestimable summe of money.” Around the same time, the bodies of soldiers hastily buried in caves after a battle near Moscow proved a rich source of saltpeter, which was fashioned into new powder to facilitate the deaths of other men, a macabre kind of recycling.

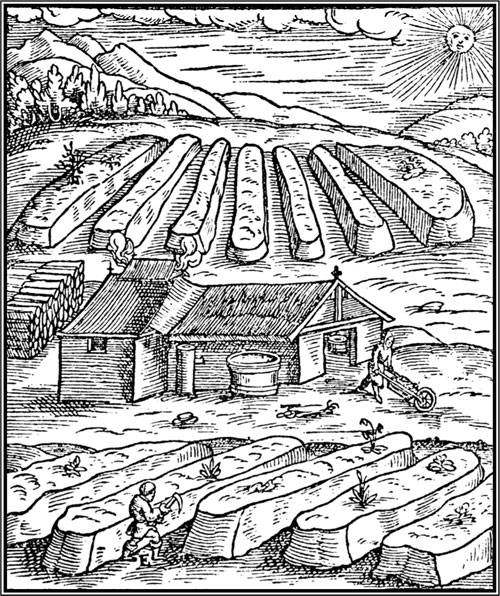

Having observed where they could find saltpeter in nature, craftsmen of the late fourteenth century began to create the same conditions artificially. These attempts to hasten the decay of organic materials and prevent the runoff of the nitrate salts developed into saltpeter plantations, which were an elaboration on the simple compost heap. The first record of one is in 1388 Frankfurt. By the following decade, artificially produced saltpeter was fueling a more abundant supply of gunpowder.

A 1598 depiction of a saltpeter “plantation” and refinery.

The process was not difficult—anyone with a covered pit or cellar and a supply of manure could get into the business. A saltpeter recipe from 1561 suggests mixing human feces, urine, “namely of those persons whiche drink either wyne or strong bear,” dung “of horses which be fed on ootes,” and lime obtained from old mortar or plaster. The knee-deep pile was to be kept sheltered from rain and turned regularly for a year. Saltpeter would then emerge “like snow.” The prescription for the piss of boozers was not fanciful—the metabolization of alcohol produces urine rich in ammonium, a food that nitrate microbes thrive on.

Gunpowder makers had to process a hundred pounds of scrapings to yield a half pound of good saltpeter. Workers leached water through the foul mass to dissolve the nitrates, then crystallized them out of the resulting solution. Here they ran into a problem. The best form of saltpeter for making gunpowder was potassium nitrate, but most of the nitrate salts produced in nature were those of calcium. Calcium nitrate served well for fashioning the explosive, but it had a quality that created difficulties later—it absorbed water from the air, eventually rendering powder damp and unusable. The gunpowder that European craftsmen made in the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries included a large proportion of calcium nitrate and the problem of spoilage by damp was widespread.

The plantation production of saltpeter, known as “petering,” became a cottage industry in some countries of Europe, a part-time occupation for anyone who could tolerate the stench. Plantations made larger quantities of powder available and played a role in the spreading use of gunpowder weapons in the fifteenth century.

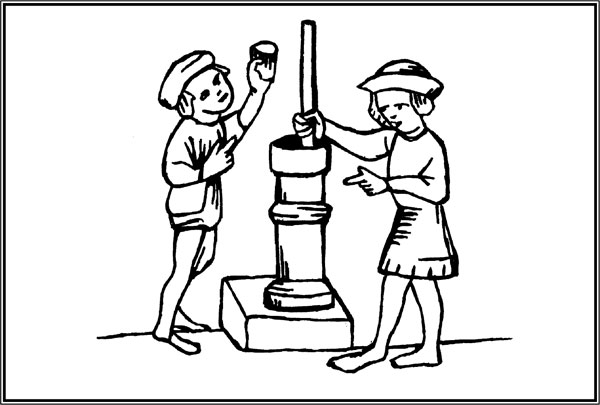

The powdermaker, once he had assembled the three ingredients, had to grind them together in a mortar. The proportions were important, but recipes of the time already approximated what are now known to be the ideal percentages: 75 percent saltpeter, 15 percent charcoal, 10 percent sulfur. “There is a certaine proportion of Perfection, of these three Components,” an early observer noted, “And that in such sort, as if you adde more or lesse Petre, the Violence shall abate.”

Intimately mixing the ingredients could take a day or more of relentless pounding. In the process, these three harmless, naturally occurring substances combined physically, not chemically—each retained its nature and could be separated out. Yet the common ingredients took on a new life, an edgy and esoteric relationship with fire, an ability to explode with the greatest violence.

EDWARD III paced the battlefield at Crécy the morning after the fight, surveying the carnage. A French herald accompanied him to help identify the dead. King John of Bohemia. The Count of Lorraine. The Count of Flanders. Barons, earls, noblemen of the highest rank, knights by the hundreds. Certainly the fight had been, as one chronicler noted, “very perilous, murderous, without pity, cruel and very horrible.” The result was a shock to the French—even the fiercest pitched battles in medieval times had rarely seen such slaughter.

Fourteenth-century craftsmen grinding gunpowder

Gunpowder had played mainly a psychological role in the fight, frightening enemy soldiers and horses, boosting English morale, adding to the confusion in the French ranks. It had yet to establish a dominant position in war, but Edward and the rulers of his generation had glimpsed the possibilities in this novel and unique form of concentrated energy.

The war Edward had started was far from over. It would go on beyond his lifetime, beyond the lifetimes of his children’s children. Northwestern Europe, during the protracted struggle of the Hundred Years’ War, would be a sorry place, wracked by spasms of violence even as the Black Death robbed the continent of 40 percent of its population. During the desperate competition over who would rule France, a steady parade of kings would probe the possibilities of gunpowder.