6

CONQUEST’S CRIMSON WING

WHEN PORTUGUESE explorer Fernao Peres sailed his small fleet into Canton Harbor in 1517, he saluted the onlookers with a blast from his shipboard cannon. The concussions of the guns “shook the earth,” echoed over the city, alarmed the locals, and drew angry protests from officials. As a Chinese historian later noted, “It had never before occurred to the Chinese that in some part of the earth a demonstration of war implements could also be an expression of respect or courteous recognition.”

The incident embodied both a crucial misunderstanding and a deep historical irony. Gunpowder, invented five centuries earlier by the ancestors of those who crowded the Canton docks, had returned in a new and suddenly menacing form. The blasts of the cannon were emblematic. While the new explosive had seriously disturbed the peace of Europe, its effects around the world would be even more jarring and consequential. In a relatively short time, gunpowder would radically alter relationships between Europeans and peoples in diverse areas of the globe.

Before gunpowder’s invention, conquest required sending contingents of soldiers to exercise power over distant peoples. The conqueror had to transport his troops, sustain them, and inspire them. Disease, injury, fatigue, hunger, disloyalty, and the temptation of booty all limited the effectiveness of men’s muscles as a tool of dominion.

Gunpowder’s destructive energy could be contained in a wooden cask. It needed no sustenance, was immune from illness, never mutinied. The ambitious ruler could transport it great distances at little cost. With the development of corned gunpowder and the improvements to cannon in the fifteenth century, a potent new means of extending political authority lay in the hands of European monarchs.

They faced one serious obstacle: cannon remained unwieldy instruments. The difficulty of moving them blunted gunpowder’s effectiveness. Big guns sank into the mud, broke bridges, taxed the strength of draft animals, slowed armies to a crawl.

The answer lay in a maritime revolution that was taking place in northern and western Europe at almost the same time that gunpowder technology was reaching a new level of effectiveness. The sailing ship was developing into an ideal vessel for transporting and using guns effectively. Just as the adoption of gunpowder had introduced a dramatic shift in mankind’s conception of energy, the new sailing ships overturned ancient notions of sea warfare.

The great sea powers of medieval times—Venice, Genoa, the Ottoman Turks—all relied on the galley as their principal fighting ship. Driven by one or more banks of oars per side, each oar pulled by as many as five rowers, these sleek vessels were fast and maneuverable, the epitome of efficient muscle power. A commander would try to drive the ram that jutted from the prow into an opposing vessel. Or he would close with the enemy, allowing a contingent of soldiers to swarm over the sides and engage in an armed melee. The violence was sharply concentrated. “Battles at sea,” wrote medieval chronicler Jean Froissart, “are more dangerous and fiercer than battles by land, for on the sea there is no recoiling or fleeing.”

Galleys had rudimentary sails, but rowers were essential for acceleration, maneuverability, and propelling the ship in calm conditions. A man pulling an oar generates only one-quarter horsepower of energy. Thus two hundred or more rowers were needed. Captains had to provide food and especially water, but the light ships had little cargo capacity. They could not remain at sea for more than a few days. The vessels needed relatively low sides to accommodate the oars, limiting their seaworthiness in storms. In the Mediterranean, where weather was predictable, tides minimal, and ports common, galleys reigned. Long voyages, large swells, and strong currents all challenged their capabilities.

Sailing ships reversed the advantages and drawbacks of galleys. High-sided and seaworthy, they were relatively difficult to maneuver, unable to accelerate on command, helpless when becalmed. As the dark ages waned, mariners had taken increasing advantage of sailing ships as trading vessels. They improved handling by replacing the steering oar with the sternpost rudder, which dropped straight down at the rear of the ship, and by adding more masts and refining the rigging of sails.

The improved ship offered an ideal platform for moving cannon—the ships’ buoyancy countered the guns’ enormous weight. But strategists quickly realized that sailing vessels could do more than transport ordnance. Ships could maneuver their batteries adroitly, bringing them to bear on a vessel or coastal position. The guns could give ships a new and devastating means of inflicting violence on the enemy.

Wind power meant that sailing ships could be handled by a small crew that was easily sustained. Their range was virtually unlimited. On arriving at their destination, the crew possessed a powerful tool for gaining an advantage over an opponent—they only needed to unpack the potential energy hidden inside their barrels of gunpowder.

THE MAN WHO found himself at the center of this dual energy revolution of sails and guns was the Portuguese captain Vasco da Gama. An intrepid mariner and a tough veteran of wars between his country and the kingdom of Castile, Da Gama was chosen by King Manuel I to command an exploratory journey to the East. He left Portugal in July of 1497 with four small ships, 170 men, and 20 cannon. He sailed down the coast of Africa, rounded the Cape of Good Hope, and continued into the unknown. His epic voyage, far more daring than that of Columbus five years earlier, brought him to the western coast of India in 1498.

The 38-year-old explorer was outclassed in the sophisticated trading world of the Indian Ocean. The gifts he brought to the ruler of the city of Calicut—some hats, six wash basins, two casks of honey—were insulting trifles, “the poorest merchant from Mecca gave more.” No matter. Da Gama had found the route to the East. When he returned to India four years later, this time with ten ships, the casks in his hold contained not honey but gunpowder.

Da Gama had two motives for unleashing violence on his return. First, he had few other assets. Europe was still a backwater compared to the advanced societies of the East. The Indians had little desire for European goods, whereas European demand for spices made pepper the “black gold” of the day. One of the few exports that the Portuguese could offer was violence itself. It proved a formidable commodity. Da Gama’s powerful gunpowder, iron cannon, and solid ships gave him an advantage over the meager guns and light vessels of the Indian Ocean traders.

The second stimulus was an irrational antagonism toward non-Christians, Moslems in particular. In part, this was a holdover from medieval thinking—Da Gama was a member of the military Order of Santiago, a knightly fraternity with roots in the Crusades. In part, the hostility was related to the very real threat that the successors of Mehmed II were presenting to Europe as they encroached on the eastern Mediterranean and moved inexorably through the Balkans. Da Gama’s commercial considerations were reinforced by the goal that one conquistador described as “quenching the fire of the sect of Mahomet.” A sixteenth-century diplomat summed up the mind-set of the conquistador: “Religion supplies the pretext and gold the motive.”

The Indians had long possessed gunpowder technology. As early as the 1300s they had hired Turkish and European technicians to teach the fine points of grinding powder and shooting. Powder production was no problem, as India possessed the most abundant sources of saltpeter in the world. Yet the gun did not attract their focused attention as it did that of Europeans. The Portuguese astounded the natives with their guns, which fired “with a noise like thunder and a ball from one of them, after traversing a league, will break a castle of marble.”

Da Gama wasted no time in putting his gunpowder superiority to use. He blasted stones at the recalcitrant Hindus of Calicut and set up a blockade to enforce his demands. He engaged in savagery that included burning women and children alive and sending a boatload of hacked-off heads and limbs into Calicut as a warning against resistance. Local powers were outraged. They assembled a flotilla of hundreds of ships and sent them out to attack the Christians. The battle that Da Gama was about to fight would offer a graphic illustration of how gunpowder had tipped the scales of power at sea.

THE MARRIAGE OF gunpowder and ships, like many marriages, was both an ideal match and a relationship fraught with problems. Ships were the perfect way to transport and maneuver guns. But gunpowder carried a severe danger of fire and explosion, terrifying prospects on a vessel constructed of wood, pitch, and canvas. Controlling the violent recoil of the guns when they fired presented a particular challenge in the cramped interior of a ship. Aiming cannon on a heaving vessel was a chancy enterprise even for a skillful gunner.

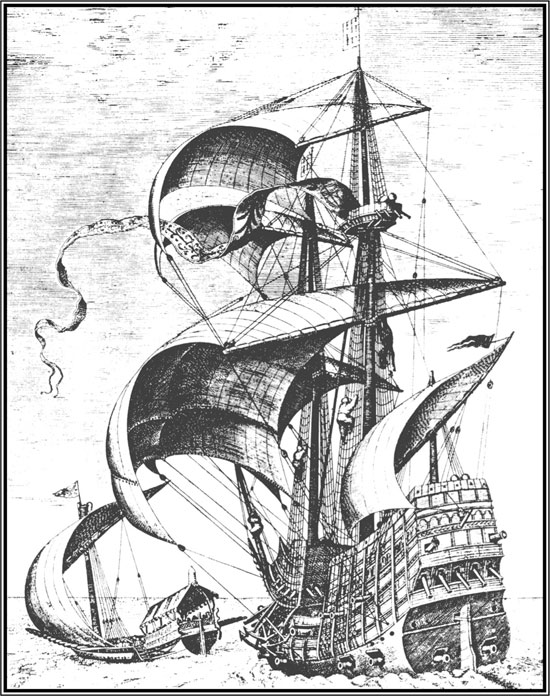

Pieter Brueghel’s depiction of a sixteenth-century war ship

Warriors had loaded guns on ships as far back as 1337, when the English sailing ship All Hallows Cog carried “a certain iron instrument for firing quarrels and lead pellets with powder.” The earliest guns were mostly small pieces of ordnance fired to repel boarders or to harass the enemy at close range. Many were mounted on “castles,” towering structures added to the bow and stern of ships to replicate the defensive advantage of castles on land—a high, protected position from which to fight. With the development of iron bombards, naval guns grew larger and better able to direct potent fire against enemy vessels.

Da Gama’s crew watched the approaching Moslem fleet from over the rails of thick-sided, high-castled, and heavily gunned ships. The sound of gongs and war drums mounted to a pulsing clamor. His forces outnumbered, Da Gama quickly improvised a new tactic: He gave orders not to come to close quarter and not to board enemy vessels. He would fight a standoff battle. His ad hoc fighting method would mark the beginning of a new era of naval warfare, one in which gunpowder played the principal role.

The Portuguese captain was playing to his strengths. His largest ships each carried thirty-two sizable cannon, guns far more lethal than those of his adversaries. His crews stood ready with bags of pre-measured, corned gunpowder to reload the pieces. The massed Arab boats were an easy target. He brought his ships around so that their sides faced the approaching enemy.

The cacophony of war drums suddenly shrank to insignificance as the great guns roared. Stones tore into the light Moslem ships, often sinking them with a single shot. “It was not possible to miss,” a participant reported.

The Portuguese forces won a decisive victory. Da Gama demanded that the owners of local trading ships purchase licenses, cartazes, if they did not want the same treatment that the Calicut fleet had just received. Forced trade became a standard practice—monopoly rights were granted to charter companies, who used gunpowder to assure their profits. The Europeans benefited from the divisions within the highly competitive trading community of southern Asia. Local potentates, hostile to their neighbors, curried favor with the intruders to gain an advantage. The Portuguese were able to maintain their lucrative monopoly with a force of fewer than 10,000 men.

In 1509 the Sultan of Egypt organized a formidable fleet of galleys in an attempt to reestablish Arab trading rights in the Indian Ocean. In a battle off the Indian port of Diu, Portuguese weaponry again proved its superiority. It was to be the last serious defiance of European hegemony in the region for a century. The next challenge to the Portuguese would come not from an Eastern power but from the encroachment of the Dutch, who could match them gun for gun.

AS WITH ARTILLERY on land, the development of guns at sea required enthusiasts who were willing to bear the expense and supplant traditional methods of fighting. England’s Henry VIII loved guns. He hired continental gun casters to set up operations in England and foreign naval architects to improve his warships.

Coming to the throne in 1509, the 18-year-old Henry took advantage of a simple but crucial innovation: the gun port. Until his time, commanders had positioned their guns on the open top deck to fire over the rails or “gunwales.” The gun port was a hinged door built into the side of the ship that allowed cannon to fire from the lower decks. Their use meant that ships could carry more and heavier guns on decks just above the waterline. When the ship was sailing, the ports, closed and caulked, kept out the sea. During a fight, gunners swung the small doors open and fired out the side of the hull.

Ships changed in other ways. As the tactic of boarding enemy vessels faded, the castles shrank and disappeared. Once gunfire began to dominate, wooden castles offered inviting targets and scant protection. The term “forecastle” for the front part of a ship is the fossil of an obsolete design. Naval architects flattened decks and cleared encumbrances to give room for firing large cannon. They built ships wide at the water line to provide additional stability.

Henry also profited from technical advances that made it feasible to cast iron on a large scale. Much cheaper and more readily available than copper, iron had to be worked at the higher temperatures made possible by the blast furnace, which was then spreading through Europe. Gun casters designed the new cannon with thicker walls than bronze pieces to make up for the greater brittleness of cast iron. When it came to shipboard or coastal defense guns, the extra weight mattered little. Founders working in iron eschewed the ornate decorations that had become a hallmark of bronze guns. The new guns, painted black, were strictly utilitarian. The English began to fit out their warships with iron guns in 1534. They would soon develop a vigorous export trade in the less expensive weapons.

The development of the British navy under Henry VIII threatened the continental powers. The Spanish king Philip II was keeping a desperate hold on rebellious territories in the Netherlands even as he attempted to ward off the English pirates who were harassing the flow of goods from his new American empire. Forty years after the death of Henry, Philip hit on an immoderate solution: to invade England, now ruled by Henry’s daughter Elizabeth I. He appointed the Duke of Medina Sidonia, a circumspect nobleman with little naval experience and grave doubts about the enterprise, as commander of a large fleet of warships.

In 1588 Medina Sidonia brought his “Invincible Armada,” the greatest war fleet ever to set sail, to the English Channel to support the invasion. The English countered with warships that were the product of almost a century of development. The Spanish captains, though their ships were equipped with guns, still clung to the outdated tactic of closing with the enemy in the medieval manner. English commanders, with better guns and more maneuverable ships, fought the type of stand-off battle that Vasco da Gama had originated at the beginning of the century. Gunpowder, not ramming and boarding, decided the issue in favor of the English.

“Experience teacheth how sea-fights in these days come seldome to boarding,” an English commission on reform noted a few years later, “. . . but are chiefly performed by the great artillery breaking down masts, yards, tearing, raking, and bilging the ships.”

THE RIPPLES SET off by gunpowder’s inception in medieval China continued to wash around the globe, affecting diverse societies in diverse ways. Like the Europeans, the Ottoman Turks saw in the explosive a tool that could help them realize their imperial aspirations. Mehmed II, known after his victory at Constantinople as “The Conqueror,” had been inspired by the success of his monster guns. During the second half of the 1400s he marched through the Balkans, capturing Serbia, Bosnia, and Albania and sending dismay through Christian kingdoms. Europeans, divided and with limited means for confronting the Turks’ deadly cavalry, feared the worst.

Mehmed approached the forbidding problem of transporting his super-cannon by casting them on the spot, as he had done at Constantinople. For the siege of Rhodes in 1480, he hired gunners to make sixteen pieces, each 18 feet long and more than 2 feet in diameter. The Ottomans became famous for their giant bombards; a seventeenth-century European commentator marveled, “the Turks have such huge guns that they can tear down battlements only by their noise.”

The guns’ success seduced the Turks down the path of a dead-end technology. The gargantuan artillery pieces, as European powers had learned, were too slow and too heavy. Western armies were moving toward smaller, lighter guns fueled by fast-burning corned powder. The Ottomans, failing to grasp the advantage of the new guns, slipped behind in the arms race. Their momentum carried them to the gates of Vienna in 1529, but there they stalled.

In Japan, Lord Tokitaka had seen a Portuguese visitor fire an arquebus to knock a duck from the sky during the 1540s. He was so impressed that he handed over a small fortune in gold to buy the firearm. He ordered his expert swordsmith to copy the weapon. Gunpowder found fertile soil in Japan. The ceaseless wars among feudal lords encouraged craftsmen to continually improve the handheld firearm. They added an adjustable trigger pull and a lacquered box that protected the match and priming powder from rain. By the 1570s, these weapons had become an important part of Japanese arsenals. Lord Oda employed 10,000 arquebusiers who laid down a disciplined volley fire on the forces of a rival lord.

Yet with the arrival of the seventeenth century, the Japanese began to distance themselves from gunpowder. The government ordered both powdermakers and gunsmiths to clear their activities through a national commissioner of guns. Rather than advance the weapons’ effectiveness, the shoguns stifled it. Over the next two centuries the use of powder dwindled until it virtually disappeared.

This long period of retrogression remains a curious eddy in the flow of history, one that raises fascinating questions about the idea of progress itself. To the Western mind, technical advances moved in one direction. The discovery of gunpowder was a momentous and irreversible milestone on the path of history, its increasingly effective use a foregone conclusion. European historians offered gunpowder as proof that Europe was immune from ever again being overtaken by the barbarism that had defeated the powderless Romans and Greeks. Gunpowder was civilization. For the Japanese, aesthetics, tradition, and politics trumped the advantages of gunpowder for more than two centuries. The Japanese would not turn to gunpowder again until well into the 1800s.

When Europeans arrived in the Americas, they came to a land where gunpowder was utterly unknown. Hernán Cortés described himself as “the instrument selected by Providence to scatter terror among the barbarian monarchs of the Western World and lay their empires to dust.” The band of about 650 mariners and soldiers that he led from Cuba to the coast of Mexico in 1519 included thirteen arquebusiers. He also brought along ten heavy cannon and a supply of gunpowder. He put in charge of his artillery a man named Mesa, who had served as an engineer in the Italian wars. Mesa made effective use of his cannon when the Spaniards landed at Veracruz and the Aztec ruler Montezuma sent five emissaries to size them up. According to the Aztecs, Cortés had them bound and fired the “great Lombard gun” as a display. The shock of the sound, the Indians said, caused them to faint dead away. The emissaries took the alarming news to the capital. The very noise of the weapon weakened one, they reported. Showers of sparks belched from its mouth, along with fetid smoke.

The flash and roar of the cannon astounded the Indians, just as they had shocked early European troops. Again the guns’ theatrical role supplemented their destructive power. In his 1521 siege of the Mexican island capital Tenochtitlán, Cortés fired bombards from brigantines, demolishing the city building by building over a period of three months. The guns contributed to the demise of the Aztecs and helped bring about European domination of the New World.

At the end of the seventeenth century, the people of West Africa were being ravaged by the terrors of the Atlantic slave trade. One of the questions that mystified them was how the European traders—the red-skinned followers of Mwene Puto, Lord of the Dead—went about transforming human bodies into the trade goods that they brought back on their ships. The natives imagined that the white men, taking advantage of the fires of Hell that flared in the Land of the Dead, burned their black captives and ground their scorched bones into a powder. Packed in iron tubes, the black dust transformed itself again into fire and spewed pain and death whenever the violent and unpredictable people desired.

After textiles and liquor, gunpowder was the commodity most frequently bartered for human flesh. The Portuguese, concerned about proliferation of a dangerous technology, banned the importation of powder and muskets into Africa, but traders knew how valuable the commodities could be and smuggling was rife. The English and Dutch slavers had no compunctions about shipping gunpowder to Africa by the ton.

On yet another continent, gunpowder’s magical connotations increased its impact. Firearms extended and reinforced a native ruler’s supernatural powers. The intimidation of noise and smoke were as important as accurate fire. The growing dependence of tribal leaders on imported gunpowder further accelerated the practice of searching out captives and trading them to the foreign purveyors of death. The traders kept herding victims onto ships—their bones kept returning as barrels of the coveted explosive.

When the Portuguese arrived in China by ship in the early 1500s, they found that the Chinese had “some small iron guns, but none of bronze.” “Their powder is bad,” an observer noted. If the guns fired by the rude Portuguese offended the Chinese, such firepower could not fail to attract them as well. In 1522, government officials recruited two Chinese who had worked on Portuguese ships to explain the mystery. Later they turned to the Jesuits who had ventured east in search of souls. In the 1640s a German cleric built and operated a cannon foundry near the Imperial Palace. A generation later, Chinese officials imposed on Father Ferdinand Verbiest, a native of the southern Low Countries, to take over the operation. Verbiest protested that he was “little instructed in those affairs,” but the emperor insisted. Taking information from books and passing it on to the workmen, Verbiest restored 300 old bombards and produced 132 smaller pieces. He solemnly blessed each gun and inscribed the names of saints and Christian symbols on the bronze barrels.

By the middle of the seventeenth century, the Chinese knew all the “secrets” of effective artillery. Yet neither their long history with gunpowder and metallurgy nor their proven ingenuity allowed them to match Western firepower. The reason is as elusive as it is historically intriguing.

If at times history is ruled by the authoritative voice of utility, it is at other times nudged forward by the whisper of taste, of fashion, of irrational whim. Chinese officials lacked the enthusiasm for guns that marked the leaders of European countries, from Edward III down to Napoleon Bonaparte. The denizens of the Chinese court looked on gunpowder technology as a low, noisy, dirty business. The fact that guns were useful did not matter, usefulness lacked the overriding value that it held for occidentals. What was more, the new cannon were foreign. To accept the ways of barbarians as superior and emulate them were deeply distasteful notions to Chinese mandarins.

The real reasons for the gap in gunpowder technology between Europe and the rest of the world remain both complex and obscure. When they fought the Europeans in the Opium War of 1841, the Chinese were still using Portuguese-made guns dating from 1627. In the end, a Chinese scholar was left asking, “Why are they small and yet strong? Why are we large and yet weak?”

ONCE THE STAND-OFF gunpowder fight became the standard way of delivering violence at sea, maritime battles changed little from one generation to the next. During the two hundred and fifty years that followed the Armada campaign, naval commanders directed artillery duels fought on wooden ships armed with smoothbore muzzle-loading cannon. Fighting in the era of the Napoleonic Wars differed only in detail from that in the days of Armada.

The mastery of gunpowder at sea required a man of extraordinary temperament and diverse skills. “A Gunner ought to be sober, wakeful, lusty, hardy, patient, and a quick-spirited man,” a sixteenth-century writer advised. Three centuries later, Herman Melville, serving on a man-of-war, described the gunner firing his enormous artillery and, “with that booming thunder in his ears, and the smell of gunpowder in his hair, he retired to his hammock for the night. What dreams he must have had!”

Some of the nightmares that troubled the gunner’s sleep involved the control of the violent recoil of his pieces. Simple mechanics dictated that the force pushing the gun backward was equivalent to the impulse that drove the cannonball ahead. On land, artillery captains allowed the piece to dissipate its force by lurching rearward. A ship offered little room for such a system. Gunners first let the ship itself absorb the gun’s recoil. With a fight impending, they situated the gun jutting from its port and lashed it firmly to the ship’s side. A man had to squeeze through the gun port and sit astride the barrel to reload. Jon Olafsson, an Icelandic gunner with a Danish fleet, performed this duty near Gibraltar in 1622. “The ship rolled all the starboard guns under, and me on my gun with them,” he reported. “I swallowed much water and was nearly carried away.”

A better solution was to allow the gun some recoil, but to restrict its range. Gunners designed a heavy oak framework that held the gun barrel by its trunnions. The weight of the timbers added to the inertia of the piece, absorbing some of the kick. Small wooden wheels on this carriage made the gun movable. A heavy breeching rope attached to the ribs of the ship on both sides and looped through a ring at the rear of the cannon brought the recoiling gun up short. With the gun thrust inboard, the crew could reload more handily. Once the piece was again ready to fire, the sailors heaved on tackle running through two sets of blocks that linked the gun to the side of the ship, hauling the muzzle out of the gun port for firing.

In spite of all precautions, there was an ever-present danger that a gun might break away from its breeching. The term “loose cannon” has become a commonplace. The reality of a three-ton mass of iron wheeling up and down the deck of a ship in heavy seas was truly terrifying. A runaway gun, “is a machine transformed into a monster,” Victor Hugo wrote. “That short mass on wheels moves like a billiard-ball,. . . shoots like an arrow from one end of the vessel to the other, whirls around, slips away, dodges, rears, bangs, crashes, kills, exterminates.”

If runaway cannon troubled the gunner’s sleep, the danger of the volatile explosive in his charge engendered even starker visions of catastrophe. Warships carried several tons of gunpowder in their holds. A spark from two bits of metal clicking together could obliterate the vessel in an instant. The gunner required all fire on board to be extinguished before he supervised the loading of this massive quantity of explosive. He stored it in a magazine in the lowest part of the ship, where it would be most secure from enemy fire. He regularly turned the barrels over to counteract the tendency of the ingredients to form clumps. Because damp was a serious problem at sea, the gunner had to air his magazine regularly. If the ship was to lay over in a warm climate, he might even remove the entire store of powder to let it dry on land.

The magazine was the gunner’s sanctum sanctorum. He secured it with a massive padlock—no one was to enter without permission from the captain himself. A marine sentry with a loaded musket stood guard over the precious cargo. This was not only a safety precaution. Mutiny was a very real danger on a vessel far from land and manned by impressed seamen subject to severe living conditions. Gunpowder represented the root of all power on the ship—a group of rebels who took over the magazine effectively gained control of the vessel.

The gunner coordinated his activities with a master-at-arms, who was in charge of training the men in shooting muskets, blunderbusses, and pistols. These small arms were distinguished from the “great guns” or artillery pieces. Marines—onboard soldiers—used the former to fire on enemy troops from perches on the masts, for repelling boarders, and occasionally for boarding an enemy vessel.

Guns on both land and sea gradually gave up their evocative names and were thereafter classified by the weight of the shot they fired. A 32-pounder, a gun used as the main battery of a ship, threw a cannonball of that weight, an iron sphere just over 6 inches in diameter. The gun itself weighed close to three tons. This mass of metal was needed to contain the blast of 10 pounds of gunpowder. The ball from this gun became a truly lethal instrument when directed against a wooden ship.

THE APPALLING intensity of sea battles can perhaps best be envisioned through the freshest eyes on board: those of the ship’s boys. A large warship carried forty or fifty boys, about ten percent of the crew. A few were children of the wellborn, midshipmen learning to be naval officers. Most were delinquents or charity cases, poor urchins put to work at a young age. They were supposed to be at least thirteen years old, but many were ten or eleven, some as young as six. They performed menial tasks like cleaning the ship’s pig pen, playing drums and fifes, acting as servants to officers.

During a fight, though, the boys were given a crucial assignment. They served as “powder monkeys,” their job to hurry up and down from the magazine carrying the packages of explosive to the guns, most of which were arrayed on one or two enclosed decks below the open main deck. The danger of stray sparks meant they kept the cartridges either under their coats or in wooden or leather containers.

In the magazine, the gunner and his mates worked by illumination that seeped in from an adjoining light room, a closet containing lanterns whose light shined through thick bull’s-eyes of glass. The gunner loaded his gunpowder into cartridges, sacks made of paper, silk, or flannel. The question of how much powder to use was the subject of intricate calculation and endless dispute among gunners. Manuals proposed all kinds of formulas. “Multiply the Weight of Ball by the Number of Diameters of the Chase in the Circumference of the Breech,” one advised. “The Product multiply by 6, the last product divide by 96, the Quotient gives the Pounds required to charge the piece in action.”

When a lookout spotted an enemy ship, taut expectation replaced the ordinary tedium of sailing. The crew rushed to prepare for battle. In minutes they cleared the decks, dismantling the partitions that normally formed officers’ cabins to make room for working the cannon. Gun crews opened their ports and ran out the big guns, which were kept loaded at all times. They positioned buckets of water nearby, one for drinking, one for swabbing the barrel. They wetted the decks and sprinkled them with sand for better footing. They lit long lengths of match, readied flasks of priming powder. Rushing down to the magazine, the boys brought up their first cartridges. They stood by their assigned guns, giddy with excitement.

On the gundecks, which had barely enough headroom for a man to stand upright, the crewmen stripped to the waist to prepare for the ordeal. They tied handkerchiefs around their heads, partly to keep the sweat from their eyes, partly to muffle the roar of the guns. They unloosed the breech ropes, checked the tackle and other rigging of the monstrous engines in their charge. Then they waited, “all grim in lip and glistening in eye.”

From the dimly lit deck, the crew caught only glimpses through the ports—now green water, now a far horizon, now blue sky, as the ship rolled with the swells. It was unlikely that anyone below deck would sight the enemy until a moment before the battle began. As smoke curled gently from the match tub, men turned pale, their throats clamped, their stomachs churned, their thoughts darted in a thousand directions at once. They yearned for action; they dreaded action. Then the action came.

The ship hove around. Towering white sails appeared against the blue. Below them, the menacing gape of rows of artillery pieces. Not always far off. British captains in particular were anxious to fight what were known as “yardarm actions,” exchanges of fire from such close range that the yards of the two ships almost knocked together. Gunners sometimes could thrust their rammers out the port and touch the muzzles of the guns facing them.

Taking his direction from the captain, the lieutenant gave the order: “Fire!” The whole ship recoiled. “Every mast, rib and beam in her quakes in the thundering weight of the blow she has given.” Cannon on land were loud—a row of guns firing simultaneously in the confined space of a ship produced a truly astounding roar. “My ears hummed,” Melville wrote, “and all my bones danced in me with the reverberating din.”

The boys were stunned by the sound. Their excitement transformed into wild feelings beyond words, they stepped forward, handed over their packages of gunpowder, and sprinted down to the magazine for more. Enormous clouds of sulfurous smoke surged from the mouths of the cannon. A large ship might burn half a ton of gunpowder a minute during a hot fight, clogging the decks with smoke.

The gun crew had little time to ponder the effects of their work. Their lives depended on speed. First a crewmember removed smoldering powder or debris from the last shot using a spiral of steel on a pole. Another seaman slid a wet sponge down the bore to extinguish any remaining embers. A third rammed home a cartridge of powder, followed by a cannonball and a wad of shredded hemp. A wire thrust through the vent pierced the bag of powder. The gun captain poured in fine priming powder from a flask.

Now came the heavy work of running the cannon out the gun port. A crew of eight men served the largest cannon. A 42-pounder with its carriage weighed 7,500 pounds, meaning that each man laying on the tackle had to repeatedly haul out almost half a ton of metal, an arduous chore, especially if the ship was heeled so that the slant was uphill. The work taxed the most muscular of mariners. During the wars of the Napoleonic era, the British government issued 40,000 trusses to sailors laid low by hernias.

With the gun run out, some of the crew had to hold it in position while the others adjusted the elevation, levering the breech end to the gun captain’s instructions and inserting wedges to hold it. The fact that the gun’s bore was not parallel to its tapered outer profile, combined with the ship’s rolling motion, made fine aiming difficult. English gunners usually tried to skim balls across the water into an enemy’s hull. Frenchmen often shot for their opponents’ rigging, using special projectiles, split iron balls joined by chain or bar that went spinning through the shrouds and sails.

All these strenuous and dangerous tasks had to be repeated as quickly as possible—a crack squad might get off a shot every two minutes, even one a minute. The rate of fire was important, and the speed of gun crews was honed through endless drills. During battle, screaming officers urged them on.

The boys were an essential element of this assembly line of violence. Their legs ached with the constant running up and down, their ears rang painfully, their eyes burned with the acrid smoke.

Greater horrors awaited them. Like sharp echoes, the roaring of their own guns was repeated from the opposing ship. Balls flew past with a sound like ripping canvas. Or they slammed into the hull, great sledgehammers breaking open a wall. Now the boys saw why the decks and scuppers had been painted red: to obscure the splatter and flow of men’s blood.

Chaos. A 14-year-old remembering an action called it “indescribably confused and horrible.” In one sailor’s words, “The very heavens were obscured by smoke, the air rent with the thundering noise, the sea all in a breach with the shot that fell, the ship even trembling, and we hearing everywhere the messengers of death flying.”

Fist-sized balls and lacerating splinters whizzed past at invisible speed. “I was busily supplying powder,” one combatant recalled, “when I saw blood suddenly fly from the arm of a man stationed at our gun. I saw nothing strike him; the effect alone was visible.”

One man repeated the Lord’s prayer over and over. Another reeled around in a kind of ecstasy, drunk on the intensity of the moment. Action left no room for sentimentality. “A man named Aldrich had one of his hands cut off by a shot,” a sailor observed. “And almost at the same moment he received another shot which tore open his bowels in a terrible manner. As he fell two or three men caught him in their arms, and as he could not live, threw him overboard.”

The boys enjoyed a moment’s respite from this carnage when they ducked below for more powder. The area of the ship below the waterline was the only place secure from sudden death. Commanders knew how attractive the refuge could be to fainthearted crewmen; they posted guards with orders to fire on any man who tried to descend. The boys had to show their powder containers to gain admittance. If they took advantage of the privilege and tried to hide in the hold, sentries stood by to shoot them dead.

Picking up fresh cartridges, which resembled 10-pound sacks of flour, the boys returned to the awful scene they had just left. Sometimes they were too zealous. In 1761, on board the Thunderer, the powder boys in their enthusiasm brought up powder too quickly during a night fight. The pile of explosive went unnoticed in the dark. A spark touched it off. Thirty men died in the blast.

The boys ran along the deck, dodging the guns heaving backward in their recoil, careful to avoid the jet of fire that shot from the touch-hole of each gun and scorched the beams overhead. They knew that they were hugging death. One boy had a spark reach his inflammable load: “His powder caught fire and burnt the flesh almost off his face,” an observer noted. “In this pitiable situation, the agonized boy lifted up both hands, as if imploring relief, when a passing shot instantly cut him in two.”

Sea battles are almost invariably wrapped in a cloak of glory. Horatio Nelson, who helped hone fighting tactics to a peak of brutality, now stands in state on his oversized pillar in Trafalgar Square. Yet few events, even in war, match the naval fight of the gunpowder era for sheer madness. That two bands of poor, illiterate, scurvy-ridden men, kidnapped and driven by the whip, should be induced to fire at each other from point-blank range with massive guns—it was a ritual of almost incomprehensible savagery and barbarism. That it should have continued and reached its apogee in the Age of Enlightenment is a deep paradox that any theory of political conflict is feeble to explain.