Just what did you do in the war, Daddy? And where? And with whom? And why didn’t you ever tell us?

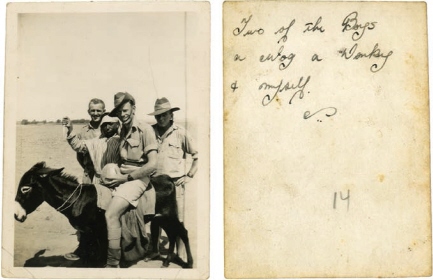

In 1941, Stanley spent his first Christmas overseas in Palestine. Here he is airing his blankets. In a few months time Pte Livingston would learn that a blanket could be an infantryman’s best friend.

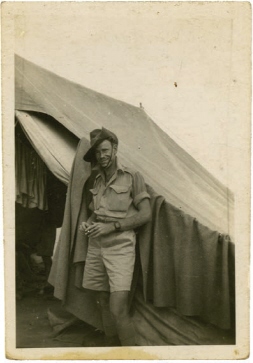

With no Christmas cards handy, Stanley cut and pasted this postcard, replacing the sights he’d seen with the one he’d most like to see. Never one for effusive prose, Stanley didn’t give much away on the reverse side, but I think Evelyn got the message.

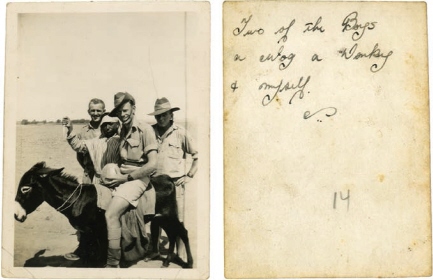

From left: E. Currie, S. Livingston, B. McGreal, L.G. McPhillips, F.W. Peters and A.H. Currie. There is no date on this photo, but from the look in Stanley’s eye and the protective touch of his hands I get the feeling these boys might have just lived through an experience they would not be too willing to share with the rest us in future. (Incidentally, Pte Alfred Herbert Currie, on the far right, was later to find out that chronic diarrhoea was no excuse for going AWL.)

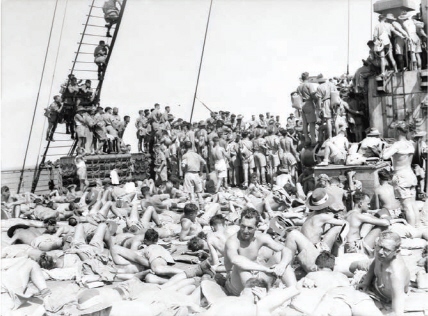

Stanley was shipped back to Australia in 1943, on board the Aquitania. The view from this ship was of a convoy of other ships, including this one, the Nieuw Amsterdam. In the background the ORs are watching a boxing match. This was a popular pastime shared by the troops, and Stanley was quick to step up to the challenge. Unfortunately, he was just as quickly put down. (Image from the Australian War Memorial.)

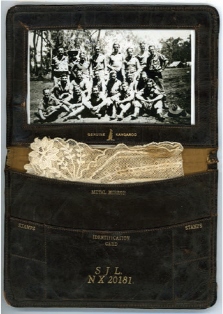

This was Stanley Livingston’s military wallet, with his initials and enlistment number stamped into the leather. Tucked below a photo of unidentified mates is a fine lace handkerchief, a keepsake from Evelyn Lonsdale on his departure to the Middle East. It never left his side while he was away.

The Livingston clan in 1924. Front row: Margaret, Molly, Stanley and Dorothy. Back row: Ernie, Lilly and Bridget. (Far back row: an advertisement for Ernie and Bridget’s favourite pastime.)

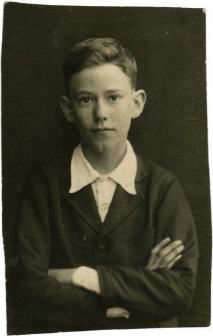

Stanley James Livingston, Catholic schoolboy and beer-bucket conveyer.

Evelyn Lonsdale, a teenager enjoying a lull between a great depression and another great war.

Billy Rudkin and Stanley Livingston, third slip and right-hand off-spinner respectively. Evelyn’s sister Dot warned her about men like these, but Evelyn was easy game for a man in pristine cricketing creams with the ability to make his late ball pitch square into the corridor of uncertainty.

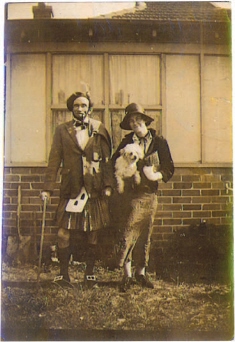

Ernie and Bridget Livingston dressed up to the kilt in Tramway Street.

Ernie the Gurner, alone and at ease.

The barber shop in Mascot in the 1940s. Taken from the vantage point of the saloon bar of the Tennyson Hotel.

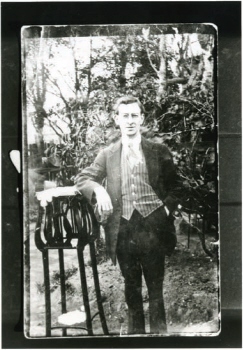

Ernest Arthur Lonsdale, apprentice barber, circa 1915.

Ernie Snr, Annie and Shiny Lonsdale on leave of their own in 1940.

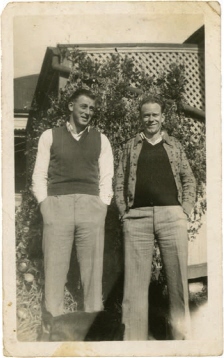

Evelyn’s brother, Pte Roy Lonsdale, and Pte Stanley Livingston in the backyard at Mascot, on official leave in early 1943. All smiles after having made it home in one piece after their ordeal in the Middle East.

Stanley found a reason to turn his leave into a stay.

Pte Gordon ‘Storky’ Oxman had his own reason: Stanley’s sister Lilly Livingston.

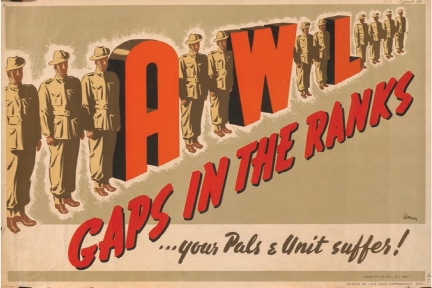

Guilt-inducing posters like these were unlikely to have prompted Stanley to return to his unit, but an increasing unease with the trifles of civilian life after enduring the realities of battle may have provoked him to rejoin the ranks of men who understood those realities. (Image from the Australian War Memorial.)

It’s hard to know when Stanley was snapped pedalling the pianola at the barber shop in Mascot. There are no known photographs of Stanley during his months AWL. In fact, the visual history of Stanley Livingston almost vanishes until the end of the war. Was it that the excitement of the first wave of the war, with the boys marching off to glory, had passed? Or had it simply been that severe wartime restrictions meant they couldn’t afford film?

While Stanley had been fighting the Desert Fox, Evelyn was taming a tree-dweller.

Evelyn and Dot Lonsdale feeding hard-earned rations to the locals on the home front. A pair of uniformed predators, no doubt armed with silk stockings, hover in the background.

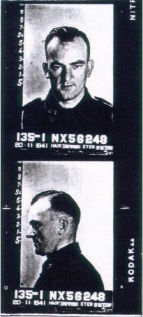

Jack Arthur Lonsdale, semi-eternal bachelor, gunner and runner. Even here in his enlistment photo there’s some hint that this would not be the last time Jack Lonsdale would have his mug shot taken.

Evelyn and Pauline, cohorts and co-workers at William R. Warner and Co. pharmaceutical company, around 1942.

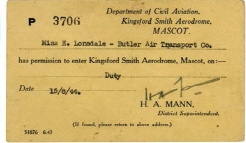

‘Is this how men earn their money?’ Evelyn’s pass into the world of male employment, riveting bombers at Kingsford Smith Aerodrome in 1944.

Evelyn gladly changed her job, and took his pay. (Image from the National Library of Australia.)

Gordon and Lilly Oxman tie the knot at St Bernard’s Church in Mascot on 15 April 1944. Pte Roy Lonsdale, Pte Stanley Livingston and his sister Dorothy were present and accounted for.

Stanley Livingston front and centre during his Pacific campaign. The story goes that this photo was taken in Borneo in 1945, and that may be so, but to my eyes that jungle looks suspiciously like the Atherton Tablelands in Northern Queensland, where the troops played a waiting game while ‘Dugout Doug’ MacArthur called the shots.

Gordon and Stanley after the war. Formerly brothers-in-arms, and now brothers-in-law.

Evelyn and Stanley in January 1946, post-war but pre-parenthood. I was at this time, as they say, just an itch in my father’s pocket.

Dot Lonsdale on bridesmaid duties at her sister Evelyn’s wedding in May 1946.

Post-nuptials, Stanley and Evelyn Livingston, with Ernie Snr keeping watch. Something in the bride’s and groom’s eyes attests that all had not quite gone to plan that day.

After his 1786 days of active service, Stanley soon found himself back on the factory floor, picking up where he had left off and where he would stay for almost forty more years. Here he is on a smoko at the factory in the 1950s, flanked by fellow toolsetters.

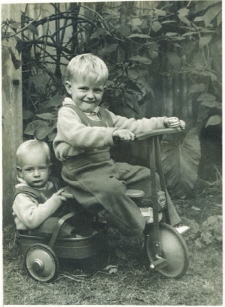

Christmas 1956. Eventually Mr and Mrs Livingston managed to go forth and multiply by two. In the driver’s seat their firstborn, Brian Ernest, went on to graduate from university and become a card-carrying member of Mensa. Holding up the rear is their last born, Paul James, who managed to fail every subject in the HSC and has never yet held down a ‘real’ job, or gained a driver’s licence. He did, somehow, manage to write this book.