20

Majd Ibrahim

Syria

ONE OF THE more baffling features of the Syrian Civil War has been the fantastic tangle of tacit cease-fires or temporary alliances that are often forged between various militias and the regime, or even with just a local army commander. These can take any permutation imaginable—radical Islamists teaming up with an Alawite shabiha gang, for example—and they pose a horrifying puzzle to anyone trying to navigate the battlefield, for it means that no one is necessarily who they seem, that death can come from anywhere. But in a curious way, this pattern of secret deal-making also served to long inoculate the Waer district from the scorched-earth tactics the Assad regime was employing elsewhere in Homs since, at any given time, at least some of the myriad rebel militias roaming the neighborhood were apt to be in secret concord with the state.

That dynamic ended in early May 2013. In a colossal misstep, the Free Syrian Army had recently moved back into the devastated Baba Amr neighborhood, and there had been surrounded and slaughtered. Those who managed to escape the regime’s cordon made for Waer and took near total control of the enclave. Sure enough, Syrian army artillery shells soon began raining down on Majd’s neighborhood. While the scale of shelling was nothing like what had previously befallen Baba Amr or Khalidiya, it was enough to keep the Ibrahim family in their fourth-floor apartment, forever trying to guess where safety lay.

“You just never knew what to do,” Majd explained. “Is it better here or in the shelter home? And if it’s safer there, how dangerous is it to try to get there?”

As bizarre as it might seem, one reason the Ibrahims stayed on in Homs despite the ever-worsening situation was that Majd’s finals were coming up at the university. Their insistence on his finishing was not some homage to the value of higher education, however; under Syrian law, male college students were exempt from conscription, so as long as Majd stayed in school, he was safe from being drafted and sent into the military meat grinder. Once he took his exams at the end of July, his parents decided, they would reassess the situation and decide what came next.

That gamble nearly led to disaster. On the afternoon of July 5, Majd was talking with friends on a Waer street when a white station wagon pulled up and three young FSA fighters with Kalashnikovs jumped out. Grabbing Majd, they dragged him into the car where, blindfolded, he was driven to their nearby base.

“I thought it was a joke at the beginning,” Majd said. “But they knew my name, my age, what I was studying in the university. They wanted me, not anyone else.”

For the next few hours, Majd’s captors insisted that he admit to being a regime spy, meeting protestations of innocence with kicks and punches. Finally, he was forced to his knees, and an FSA man put a large knife to his throat. Another aimed a Kalashnikov at his head.

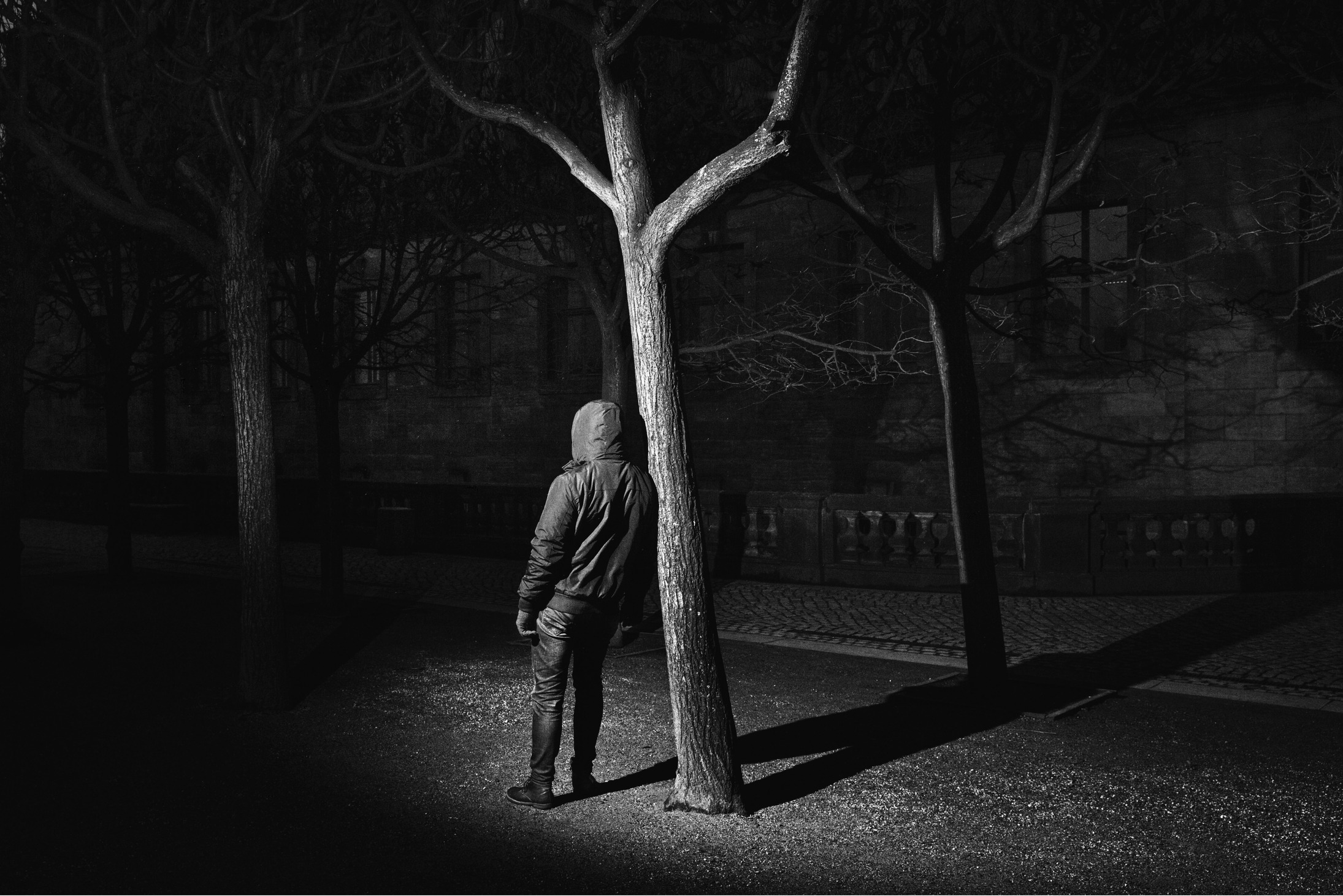

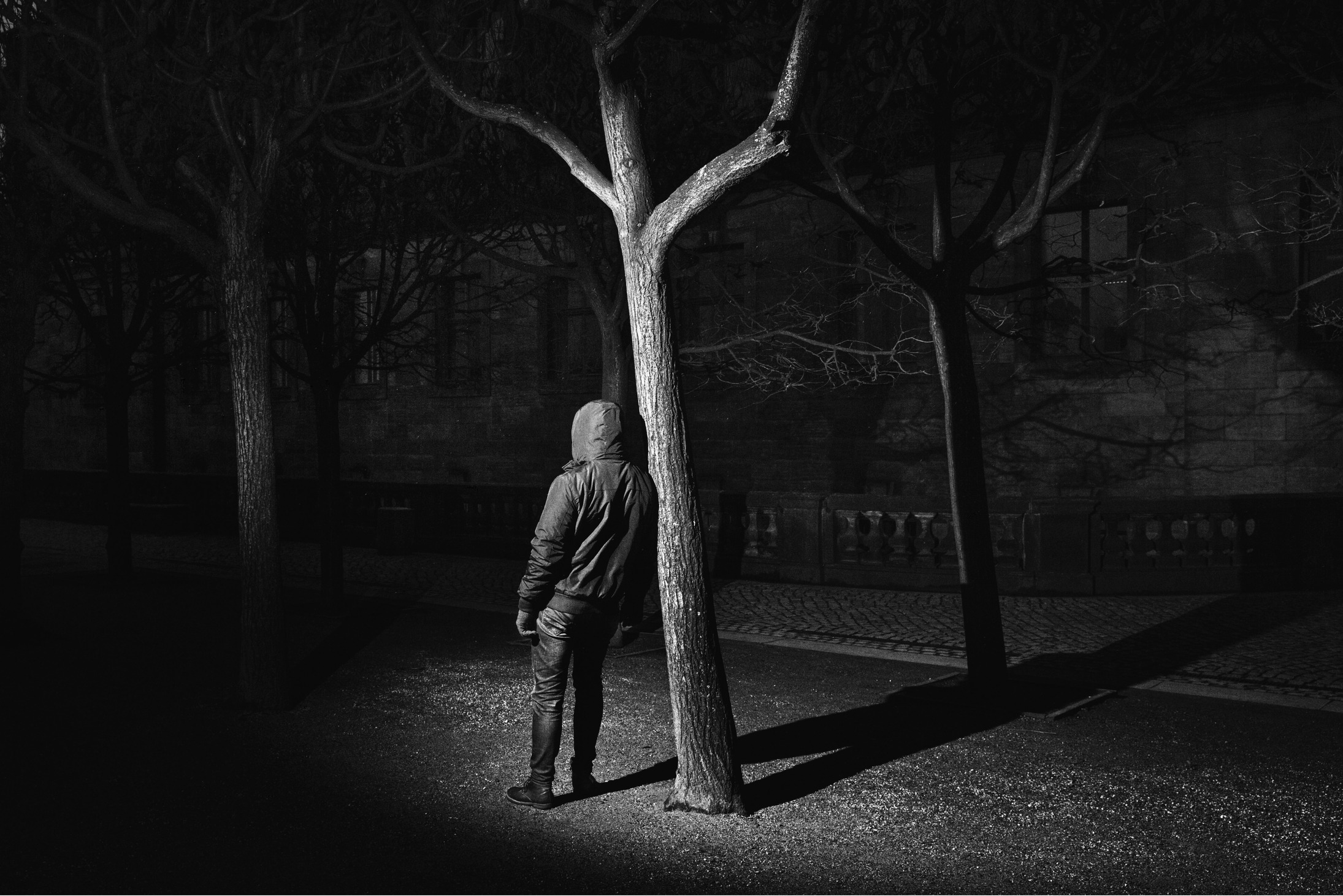

Majd Ibrahim, twenty-four

“Well, this is the standard way they execute,” Majd said softly, “so I knew this was about to happen to me. They wanted to kill me very badly.”

In prelude to his execution, however, the chief interrogator thought to look through Majd’s cell phone. With each phone number and photograph he flipped to, he demanded that Majd finally give up the identity of his “controller.” The twenty-year-old’s continued professions of innocence brought more kicks, more punches. The interrogator came to the stored photograph of one young man in particular and stopped.

“Why do you have this guy’s photo?” he asked.

“Because he’s my best friend,” Majd replied.

The FSA commander slowly turned to his captive. “We will call him.” The militiaman left the room, and for a long time Majd remained on his knees, the knife to his throat and the gun to his head. Quite unbeknown to Majd, his best friend was also an acquaintance of the FSA commander, and he came to the base to assure the militiaman that Majd Ibrahim was no regime spy. Majd learned this only when the commander returned to the interrogation room and told him he would be set free.

“So that is what saved my life,” Majd said, “that photograph.”

During the drive back to Waer, the FSA commander delivered a long sales pitch on why Majd should quit the university and take up arms against the regime. The college student said he would think about it.

When Majd arrived at the spot where he had been picked up earlier that day, his parents and friends were waiting for him. The next morning, July 6, the Ibrahim family left for their shelter home, never to return to the Waer neighborhood where Majd had lived his entire life. It was his twenty-first birthday.

Two weeks later, Majd took his exams at the university. With the city increasingly an all-out battlefield, and with his nearly fatal encounter with the FSA fresh in their memory, Majd’s parents decided that all three Ibrahim children should go to Damascus, along with their mother; Majd’s father was determined to remain in Homs.

“At that point, we had lost almost everything,” Majd recalled. “We had sold our car and most of our furniture, but I think for my father it was psychologically important to stay, to try to protect what little we had left.”

In Damascus, the veneer of normality continued, even if it had begun to fray a bit as the civil war entered its third year. While couples continued to stroll in downtown and the central bazaar remained a busy place, there frequently came the sound of distant rumbling, much like thunder, as battles raged in the suburbs.

Majd was still in Damascus in late August 2013 when he heard rumors of an enormous battle in the rebel-held neighborhood of Ghouta, with many hundreds dead. As details slowly emerged over the following days, Majd learned the August 21 death toll in Ghouta was not the result of battle but rather of a chemical weapons attack, reportedly carried out by the Syrian army.

Precisely one year before, President Obama had warned the Assad regime of the grave repercussions it would face if it ever employed chemical weapons in the war. Obama had underscored that warning as recently as March 2013, reiterating the “red line” that would be crossed by such an attack, and how it would be a “game changer” as far as the United States’ nonintervention policy in Syria. Within days of the Ghouta attack, a United Nations inspection team determined that the estimated 1,400 dead had been killed with shells of sarin gas, taken from known Syrian government stockpiles and “most likely” fired from government lines.

“When we heard that,” Majd said, “we all expected a big reaction, that the Americans would now come in.” Curiously, that expectation wasn’t shared by the Syrian military units deployed around Damascus, all of whom appeared unusually relaxed. “It was very strange, but it was like they knew nothing was going to happen.”

They were right. Although President Obama had the executive prerogative to order retaliatory air strikes, he balked in the face of fierce opposition by both Democrats and Republicans in Congress, then sidestepped the matter by requesting congressional authorization before taking any action. In a particularly humiliating gesture, Secretary of State John Kerry was dispatched to Capitol Hill to promise that any punitive military action against the Assad regime would be extremely limited, which rather begged the question of why it was being contemplated at all.

In the end, Russia, an Assad ally, saved the Obama administration further embarrassment by offering to oversee the removal of Syria’s chemical weapons stockpiles. If some in the American administration saw this as a face-saving compromise, this was not at all the way it was viewed in the Middle East. There, it served to confirm that American “red lines” were meaningless, a point that emboldened America’s enemies and infuriated and frightened its friends. In light of what was to come, it may well have been the most grievous American policy misstep in the region since the Iraqi invasion.