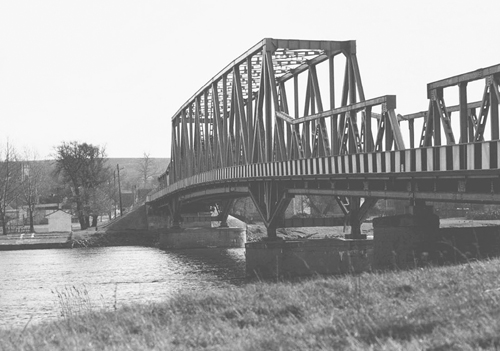

March 9, 1990. Where I am now, every place has two names. “Oder,” I say to the water in front of me, which looks so blue today; “Odra,” says the soldier on the other side of the bridge. Neisse-Nysa, Lerida-Lleida, Mons-Bergen: the contradiction of two words for one place, the mingled whispering of languages that both want something different. Claims and bloody histories are concealed within them, nostalgia and memories. Double naming, double meaning, and always with some sense of longing or loathing. I drove out of the city through the gloomy blocks of East Berlin, a light mist veiling the worst of it. The Autobahn to Szczecin, exit at Finow, into the countryside: cobbled roads, nature, Kerkow, Felchow, Schwedt, the border, the iron bridge. I follow a path down to the river, and look at the village on the other side: Hohenkränig, Krajnik Górny. Though I am a frequent traveler to the other side, it is not possible this time; I am not permitted to travel on into the East. There is no sign of movement in the Polish village, but on this side a man is screaming out his fury at two others who look a little embarrassed at the scene he is making. There are two kinds of writers: voyeurs and auditeurs. Armando, with whom I am making this short journey, is an auditeur, and has the slightly stern, legalistic aspect that the word suggests: I can see him making an internal record of the conversation, of the fury at forty years of wasted time, the cursing, the gesticulating at the other side of the river. Odra-Nysa; a spoonful of tar can spoil a vat of honey. Jaruzelski said so this week. Viewed from the side, the bridge is a tall iron skeleton. Once there must have been ferries to transport all of those armies to the other side: French, Russian, German. Border rivers, bridges—in some places, the fate of countries takes visible form.

The weather changes, the leaden darkness above merging with the decay below. In Stralsund, the rain whips the paper faces of Modrow, Gysi, Kohl, the promises of a new Unity. The city seems deserted, but the hotels are full; we cannot even find anywhere to eat. Through the storm, we see churches, merchants’ houses, an antiquated Lübeck, a city that was frozen in time just after the war. The power of belief: how was it possible to live surrounded by such obvious failure? At the Baltic Hotel, a helpful receptionist calls a seaside resort on the Baltic, on the island of Rügen. They have a room for us, but it is an hour’s drive, it will cost almost 300 guilders, and we will have to pay in West Marks. When I say it’s expensive, she replies, “You just wait. You’ll see. All the important people have stayed there. Honecker, Mielke . . . They practically had the place to themselves.” She is right. The hotel is surrounded by a ring of Mercedes and B.M.W.s, and all of the doors display a threatening notice: Nur für Hotelgäste. An ordinary person cannot even get a drink here, but an entire conference of people would be able to dance in the dining room, where the prices are in East German money, which means the Mercedes are once again eating for free. The storm is now a hurricane, and I know the invisible sea must be out there somewhere. I see Kohl on television looking like some immense marsupial that could easily accommodate the entire D.D.R. in its pouch, although lugging the country around might prove more difficult than he imagines.

When I wake up, I hear a woman’s voice on the radio frantically asking, “But what’s going to happen about abortion if we join up with the B.R.D. via Article 23?” “Well, that means abortion as we know it will become illegal here, in accordance with the West German constitution,” says the man she is talking to. He goes on to list all of the other babies that will be thrown out with the bathwater: crèches, security, women’s rights. Real, harsh, capitalist society is on its way, and she is just going to have to learn to live with it. There is almost a threat in his voice, and she finds that hard to take. “Yes, but . . .” she begins, and the dilemma and the ever-increasing speed of the changes are encapsulated in those two simple words. The metaphor of a train ploughing ahead, unstoppable, has frequently been used in recent weeks, but in fact there are two trains: there is also a slow train heading from East to West. The atmosphere of love and togetherness that reigned on the ninth of November has already evaporated. People from the East are saying that people from the West want to buy up their country at bargain-basement prices, while people from the West are saying that the East is a bottomless pit into which their hard Marks will disappear, after they have sweated so much to earn them. What is actually happening is of course extraordinary. Wilhelmine Germany races into the First World War, is bloodily defeated and mercilessly and short-sightedly punished. Then comes a brief opportunity for the oppressed working classes: Weimar, with its good intentions, chaos, inflation, scheming politicians and arrogant rejection of politics by so many intellectuals, the rise of fascism, Hitler, another war. And even though that first unity only came about under Bismarck, they had been one nation all that time, one people; it was only afterwards that they split apart. And then one became rich while the other became poor, one was helped and the other exploited, one was forced to carry the mental burden of the past, and the other the material burden, with all the mutual resentment that created. To what kind of music should these two peoples, who are almost one, but not quite, dance their duet? Beneath the loud, impulsive waltz of the new Unity, that other music still plays, so much more slowly, the music of forty years of separate lives, which no one can forget, not for money and not by decree, music that suggests different, incompatible dance steps, so that the moves of the superior dance instructor no longer look quite so masterful. History is a substance that is made of itself. If you turn away from the staccato of newspaper headlines and listen very carefully, you can hear the sound of large wheels grinding exceeding slow without letting a single grain of history escape.

Bridge over the River Oder. German–Polish border

Ostseebad Sellin, Ostseebad Binz. I look at Armando eagerly watching the death throes of the big villas, the Kurhaus amidst them like an old lady with no money left for make-up. “Dear Pensioners, Don’t give the fearmongers a chance! Say yes! For freedom and prosperity!” shouts the C.D.U. in black, red and yellow. “Into the future with optimism: 44% for the S.P.D. on Sunday,” the S.P.D. shouts back. We, the outsiders, drive through the storm in search of a mythical place in German art, the Königstuhl on the Stubbenkammer promontory on the island of Rügen, where, in 1818, Caspar David Friedrich painted his Kreidefelsen auf Rügen (Chalk cliffs on Rügen): three figures, two men and a woman, one sitting, one leaning, one on all fours, their backs to the viewer, with high chalk walls on the left and the right, looking out over the infinity of the sea. Goethe did something fiendish with that painting; he turned it upside down to create a gruesome ice cave with the three figures clinging like bats to the jagged vault. It makes me feel dizzy and I do not want to picture this scene upside down, because with Simone here, we are that group of three, and we can position ourselves in exactly the same way. I, of course, take the part of the curious fool leaning over the abyss; disapproving German voices call me back: you mustn’t do that, it’s not allowed. How should I explain? Should I say that the rail that is there now did not exist back then? Can’t they see my tall hat beside me in the grass? No, they cannot, just as they cannot see the piercing eyes of my friend the painter, or my wife’s red dress and those two white sails that, once upon a time, on that day in 1818, in that other Germany, made the sea so much larger.

And so we continue on our Winterreise: Danish and Swedish voices on the radio, lighthouses, black-tarred fishing boats upside down on the beach. Then, having wandered away from the others, I find myself standing at the end of a small road beside an iron gate with a red star. I cannot read the sign, but I do not need to. I already know what this is: it is a sentry box with a Russian soldier inside. The window of his shelter has blown away and now he has only a sheet of flapping plastic to protect him from the ice-cold wind. He is wearing a winter hat with another star on it, and he is looking at me. I can sense that we both want to say something, but then decide not to, watchman and wanderer, two foreign species in the territory of a third.

Leipzig, 13 March. A short piece in the Leipziger Volkszeitung: “HUNGARY: Soviet soldiers return home. The withdrawal of Soviet troops from Hungary started on Monday with the repatriation of a Motor Rifle Brigade.” Some things keep coming back again and again until they encounter their own echo. I have talked about this before, but it is a notion that does not seem to want to leave my system. In 1956, I went to Budapest. It was more a coincidence, a desire for adventure, than any sort of well-defined conviction: a photographer called to ask if I would go with him, as he had heard that there was an uprising. I left Budapest a few days later, just ahead of the Russian troops. I had smelled the scent of war and realized that I was still familiar with the stench of burning. Candles in windows at night: a wake for the dead. Hanged busts of Rákosi, of Stalin. I came across this image again over thirty years later in György Konrád’s The Loser, encountering confirm-ation of reality in a novel—and it proved that my memory was correct. Corpses lay in the streets and people spat on them. Banknotes in their mouths, they were agents of the secret police. Later I saw a photograph of their execution, faces you do not want to describe, that split second as hands try to ward off bullets. The world behind this world returned in Péter Nádas’s enigmatic novel The End of a Family Story, the Stalinist universe seen through the eyes of a child; betrayal and death woven into an imagination that distorts the world of adults, mercilessly exposing its unbearable truth.

Election campaign, Rügen, March 1990

They had to stay there, while I could go home. People had asked when we would come, when we would help, and there was no answer to that question, because you could not utter the only answer that there was. We would never come. I wrote my first piece, probably a bad one, for a newspaper. It ended with the sentence, “Russians, go home.” I had been given a lesson in violence and shame. Other than East Berlin, I have never visited an Eastern Bloc country since then; it was impossible for me. When I returned to the Netherlands, the mood was one of hysteria. The very fabric of The Truth was under attack, that kind of thing. The PEN Club, which I had just joined, debated the idea of expelling Communist members. That seemed to be the same thing I had just experienced, but on a small scale, and I was against it. When it happened anyway, I left the PEN Club. The Mitteleuropa I had just returned from began to turn to stone, and that stone did not shatter until recently. In the coming decades, that era will be documented—the indignities, the nonsense, the betrayal, the pettiness, the fear, the pride. But nowhere will it be captured so tragically, so cynically, so ironically, so solemnly, so hilariously as in the novels of Konrád, Hein, Moníková, Kundera, Nádas, and their ilk. Scores will be settled, as happens after every war, and profiteers and hangers-on exposed. The shining founder of the new party is the Stasi informant of yesterday; those who stay will attack those who left, and vice versa. The television pictures of the congress of the East German Writers’ Union offered a foretaste: disoriented former people of privilege watching their houses and subsidies and boltholes by the water disappear, without any idea of what was going to happen next, and gazing with envy at those whose talent or political courage had already won them a place in the West. Each of those East European communities is small enough for everyone to know everything about everyone else, but once the dust has settled, alongside the world of files, photographs, minutes, reports, another world will exist, the so much more apocryphal but also more accessible world of letters, diaries, memoirs, poems, the truth of fiction, that last refuge of the subversive imagination, of resistance.

In Leipzig, the sun is shining. I walk around the Marktplatz in front of the old town hall, read the golden letters listing the grand titles of Goethe’s duke, breathe the hazy, all-pervasive smell of brown coal and try to think about the past, but find that there is too much present. Are my memories correct? I am no longer sure. I can still see the face of a girl in Budapest, very intense, asking me when we will come. She is not the only one. What does that mean, “we”? Pincer movement: I remember that expression. The Russian tank divisions performed a pincer movement, closing their pincers on the main road to Vienna. Was it the tank divisions? What I should have seen was invisible to me at the time; I am reading it only now, courtesy of Konrád. Pre-war Hungarian Communism, collaboration, Hungarians on the Eastern front, defections to the partisans, the horror of Communist mutual surveillance—even back then, during the war, still ongoing in Russia—torture, executions, the return of the survivors, the power, Stalinism, more torture, more executions. All of that was already going on before those few days when I found myself walking among the burned-out cars, the shoot-outs, the people hunting down traitors. What makes Konrád’s book so unusual is not the litany of human cruelty and stupidity, but the studied nonchalance, the tone, which suggests that it is possible to survive anything. Torture and cynicism, the apparently unfathomable depths of evil, are described so vividly that I often have to stop reading, and sit there helplessly, a little foolishly, with my hand over my mouth, because it is unbearable. And yet, by some kind of Manichaean magic, something like hope shines through that panorama of horror, as though someone were smiling throughout, and there is healing in that smile. So now I understand what kind of world I was blindly wandering through back in 1956, where it came from, what was yet to come. The end of that era brings a sense of joy to which an outsider like me has no right, but I feel it just the same.

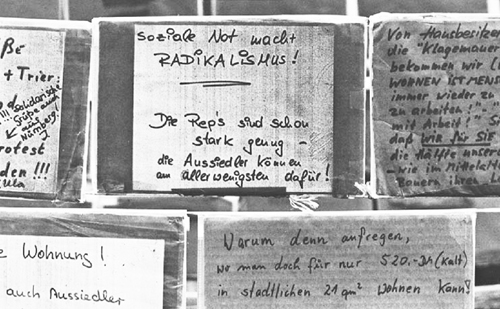

In the Marktplatz around me are other people who have more reason than I to be thinking about their past. After my return home, I still had choice, freedom. There were conflicts of opinions, the Cold War, people who continued to condone the system, friends who, for whatever reason, expected everything to turn out well, disappointed expectations in Cambodia and Vietnam. We were free thinkers, and literally so, because whatever we thought, we were still free. It all seems so far away now, those embittered ballets of right and left on the Dutch stage, but here, in this marketplace, they still continue and, for the first time, the performance is at full volume. Large circles gather around small groups who are debating about Sunday’s elections, about Gysi and the S.E.D.’s gold, about Böhme, Schnur, Modrow, about traitors and bloodsuckers, about intellectuals who think they know it all, about Stasis and Bundis, about the Bundesrepublik and how it is waltzing all over them, about money and rents and unemployment. They hold forth among the posters of Kohl and Brandt and Schmidt, the kiosks of Western newspapers; they get excited and shout as though making up for all those years of silence. The circle round them mutters approval, and disapproval.

Who were they yesterday? What novels, libretti, diaries stand beside me? The streets of Leipzig are busy, even cheerful. Paint is peeling off the houses, antiquated trams squeal along the rails, large groups of travelers stride through the enormous station on their way to a trade fair. Who are the judges, the informers, the people of last year? The question applies both to this country and to the other one. Where is the judge to whom Václav Havel made his concluding statement, ending with the words, “That is also why I trust I shall not be convicted groundlessly yet again,” whereupon she once again sentenced him to however many months? What does she think when she sees him on television with Bush or Gorbachev? Where are the officials who often decided not to hand over the letters his wife wrote to him (“. . . because, as I have been informed, you went beyond the scope of family matters and sent me various greetings”) when he was in prison from 1979 to 1983? Where are “the young men in the car in front of the house” in the latest, as yet unpublished, story by Christa Wolf? Did they see her reading that story on television? This is a reversal of fortunes of the kind that belongs in fairy tales or seventeenth-century comedies: frogs as princes, prisoners as kings, stokers as ministers, hangmen scared, judges accused. And fairy stories are grim tales: it can be fatal to end up on the wrong side. But the time for the great unmasking has not yet arrived, and maybe people do not want it to; they have other things to do.

Few novels succeed in fictionalizing reality in such a way that you are certain you have met the protagonists before, or that you might just bump into them tomorrow. One such character is Orten, from Libuše Moníková’s novel The Facade. Orten, a painter, undertakes an insane journey with his friends through the Soviet Union, heading for Japan, which seems to retreat as they move closer. Laughing at misfortune would appear to be a Czech character trait, as their journey becomes one huge, enforced delay and everything that can go wrong does go wrong, but the picture that Moníková paints of Czech–Russian relations, of absurd enclaves of Russian scientists in Siberia, the extraordinary nonsense of the system, is something I cannot get out of my head, so much so that I wish Orten were here to tell me what is really going on in Prague these days, as only a fictional character from an exemplary book can—such as Cervantes’ Novelas ejemplares—so constructing a truth out of the semblance of reality that is the world.

Clichés involve things that everyone notices, but which still need to be said. “It feels like the war just ended,” Armando said on Saturday, and it feels like that here too. It is not just the peeling paint, the antiquated cars, the bad roads; it must be something else, as if, even though the grass is green and the roof tiles are red, everything has been photographed in black and white, as though this world does not entirely want to become now, the present. And there is that slight sense of nostalgia that some people seem to feel, those who would rather things stayed as they were. It is perhaps what Günter Grass means when he says that people here live more slowly, and that is exactly what Monika Maron resists, just as she resists the dreams that Stefan Heym still wishes to salvage from the nightmare of the past. I have caught myself thinking the same way too, but it is impossible. On Sunday, the people will make their own decision about what is possible next Sunday. “Die Stunde der Wahrheit naht,” says Der Sachsenspiegel. They are right: the hour of truth is approaching. It is too early, but still I head to the Nachttanzcafé at the Hotel Astoria for a coffee. It is only ten in the morning, but those ancient times are here again: men in white dinner jackets playing ballroom music, swishing percussion, sweet violins. I become my own dead father and sit down on the plush seats. Huge chairs arranged in regiments, nooks, clusters, velvet-covered bar stools, ’50s-style, the Volksrepublik version, a backdrop of swirling, bulbous plastic, wall lights in colored frosted glass, rectangular, yellow, blood red. A sanctuary, a trolley of Kuchen, a willowy blonde, a life of privilege. I read Die Geschichte ist offen: Volker Braun, Günter de Bruyn, Sarah Kirsch, Monika Maron, Günter Kunert. Voices, dissenting opinions. I am hooked by Maron’s beautiful autobiographical piece, which, more successfully than anything else I have recently read, presents a picture, with such clarity and compassion, of what has happened to people in this century in Germany: Jewish grandfather, Catholic grandmother, Communists, deportation, neighbors who are Nazi sympathizers, but still help them, a mother who, in spite of everything, clings to the old Communist beliefs, the rift, some who go to the West and others who stay in the East, the grandfather who never comes back, reconciliation, seeing lost relatives again, fate, history that is its own explanation.

Outside, the sun denies the past. I walk through the city to the Thomaskirche. Bach is buried there, Mozart played there, and so did Schumann. Mendelssohn performed the Matthäus Passion there for the first time since Bach’s death. A photograph of Wilhelm Pieck, Walter Ulbricht and Dmitri Shostakovich at Bach’s grave. And that too prompts a memory: Ulbricht in 1963, with Khrushchev, at the S.E.D. party congress. Snow at the border, men with dogs, a blizzard on the squares where I saw the uprising last year. In front of the congress building, old women working away at red carpets as though they want to lick them clean. That high, thin, Saxon voice, the hundreds of people, their applause. That church has been dissolved; this one is still standing. Anyone who promises to accommodate not only the living, but also the dead, will himself have a longer life. The space is high and cool. I look at the stern clerical faces of the eighteenth-century Superintendenten, men in pious black, their heads served up on white ruffs. Someone is playing the organ, a form of eternity. Then someone else speaks, and eternity crumbles. I walk past political posters of Women and Greens to the book fair, where publishers from the West are busy staking their claims. On the stairs, photographs of Christa Wolf, Christoph Hein, Helga Königsdorf, Stefan Heym, Walter Janka, and I think about Janka’s trial, the betrayal of Johannes Becher and Anna Seghers, his seven years in prison and his book about it, Schwierigkeiten mit der Wahrheit (Difficulties with the truth), and then about Hein’s plea to fill the gaps in the past with the truth about those years. Autoren als Vordenker und Wegbereiter des revolutionären Aufbruchs, declare the large letters beside the photographs: “Authors as prophets and pioneers of the revolutionary awakening.” Is that really true? Or was it in fact what they had written at home, alone, without the crowd, that later, someday, would explain why those equally lonely members of that crowd, why the abstraction that is called “the people,” had gone out onto the streets of this city to do some writing of their own?

Berlin, Alexanderplatz, 16 March. Gysi is speaking. I saw him working his way through the crowd surrounded by a swirl of photographers. He is much smaller than I imagined, and his cap does not help. What is it that makes him so appealing? It must be his courage; what intelligent person would wish to inherit the burden of such bankruptcy? They are all waiting to see him and the crowd is growing by the minute. They are young, carrying flags, and they fill the large square all the way into the distance. The little man is lifted up onto a truck and I see those morello eyes flashing behind his small glasses. Und doch wird dieser schlaue Judenjunge es nicht schaffen, I heard someone say in West Berlin: And still the clever Jewish boy isn’t going to make it. That was at the beginning, but even then I already liked him. Too bad about the party he belongs to, though. On the other hand, a politician who puts you in a good mood when you see him—how often does that happen nowadays? “So do you agree with him?” someone asks me. “Hardly, but he’s got a good sense of humor,” I say, and that does not go down too well. So I add, “You know he’s received all sorts of fantastic offers from big law firms in the West.” That improves the atmosphere a little. A person who refuses money on principle is always somewhat sacrosanct. It means that he is serious.

The crowd is patient, still growing. So it looks as though he is going to win more votes than the 5 percent of the unions. One speaker after another, last but one is Janka, who did not lose his faith when he was in prison. Then comes Gysi. It is dark, the tall buildings have shed their irrepressible ugliness and are casting a circle of light around us. He speaks about the mistakes that have been made, the renewal of the party, which is far from complete, about what, in spite of everything, has been achieved over the past forty years, about the reparations that the East has been obliged to pay, but the West has not, about property and rent control, about the certainties that will disappear. I look at the faces around me. They are listening, all seriousness. He does not shout, barely argues, employs no demagogic tactics, neither does he suggest how the problems might be solved. Here is someone who is talking against the flow of history, but that does not mean that he represents nothing.

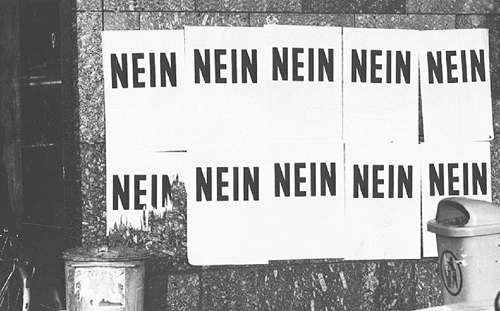

Two days later, I see him again. The cards have been reshuffled. The C.D.U. has waltzed all over the country. The socialists, led by Ibrahim Böhme, only achieved half of that 44 percent; his eyes are sad. Around midnight, I head east again. It is quiet at Checkpoint Charlie. I do not know exactly what I was expecting, but it is not here. There is a sort of party going on at the former headquarters of the Central Committee. People are walking in small groups around the large squares, while at the Palast der Republik the television companies from the West are starting to pack up their things. I walk past a wall that says nein nein nein nein, and then past a bronze plaque with a very large head of Marx and lots of little men whirling past beneath him. Walking back along Friedrichstraße, I hear some noise coming from a building. I open the door and find myself among the heroic pioneers, the small parties of the big demonstrations, the forerunners who were abandoned by the voters. A large group is standing around someone I cannot see. When I climb up onto a chair, I realize that it is Gysi. “Where were you last year?” someone yells at him, drunk and aggressive. Before he can reply, someone else has climbed onto the podium and says that Gysi defended him four years ago. He is followed by a student who wants to stand up for Gysi because he heard him years ago saying things that no one else dared to say. I wonder why he is still here, why he has not gone to bed. What does he still have to say to this handful of people after an election night like this? But then, through the greyness of exhaustion, I catch that flash of laughter in those cherry eyes again, and I know that this man, together with Modrow and his rasping seriousness, can still provide a decent opposition, and not only in this Germany. The debate continues, machines that you cannot switch off. At Checkpoint Charlie I am the only one going through. I have those neon lights, guards, corridors, doors, the whole labyrinthine route all to myself. Neue Zeit, it still says in those old-fashioned letters on the wall high above me, but that too will have gone within a year.

March 24, 1990

Elections, S-Bahnhof Alexanderplatz, East Berlin, March 1990

Marx, wall relief, East Berlin