INTRODUCTION: THE END OF RATIONING

In May 1949 clothing rationing ceased in Britain, almost exactly four years after the Second World War officially ended in Europe. Rationing was intended to offer equal shopping opportunity, ensuring that everyone, rich and poor alike, having the same clothing rations, could purchase up to forty-eight (reduced from sixty) coupons’ worth of garments per year. In practice, ration books were widely abused, stolen and forged, meaning that the scheme failed to live up to the ideals that inspired its conception. For her January 1949 wedding, a young bride-to-be, Rachel Ginsburg, bought a chic red wool suit from a Liverpool department store using coupons donated (illegally) by her classmates. The jacket’s nipped waist and flared peplum made it one of the first ‘New Look’ garments Rachel had seen, a term coined by the American fashion journalist Carmel Snow. On seeing Christian Dior’s 1947 debut collection, featuring rounded shoulders, tiny waists and long skirts, either lavishly full or reed-slim, she proclaimed it showed ‘such a new look’. Although other Paris couturiers had introduced fuller skirts and wasp waists between 1944 and 1946, Dior became the designer linked with the curvaceous silhouette that swept away the boxy shoulders and skimpy skirts of the war years. Instantly desirable to devoted followers of fashion worldwide, a whole decade later, tiny waists and full skirts were still recognisably part of the late 1950s fashion vocabulary.

By 1950 the New Look influence was firmly established in longer, mid-calf-length skirts and rounded shoulder-lines. The beautifully matched gloves, small hat, handbag and shoes epitomise early 1950s elegance. This advertisement from a 1950 trade journal promotes a new crease-resistant fabric finish.

The British response was mixed. While politicians rushed to decry the New Look as unpatriotic due to its abundant use of scarce fabrics, and King George VI forbade his daughters to wear it, many British women responded with longing. Barely a year later, even Utility dresses showed its influence, with softly rounded shoulders and skirts cleverly cut to suggest fullness. The Government-led Utility schemes, manufacturing furniture and housewares as well as clothing, were designed to offer economically made but excellent quality merchandise. Despite this, ready-to-wear clothing was seen as an extravagance, with many people wearing what they could make or afford. As a result of austerity and shortages during the 1940s, second-hand clothing became increasingly acceptable. With alterations and cleaning, garments snapped up at jumble sales and charity shops gained a new lease of life for the thrifty dresser, but were unattractive to those demanding absolute newness and freshness in the post-austerity years.

The media encouraged consumer demand for the most modern and technologically innovative textiles, fashions and housewares. Manufacturers vied with each other to offer the newest, most exciting synthetic fabrics. By the end of the 1950s, synthetic and synthetic-blend materials were widely available in every form, from gossamer chiffon to heavy tweed, sold under countless brand names. Cardigans might be made from acrylic-based synthetics such as Orlon, while a late 1950s evening gown might be made from acetate satin brocaded with metallic Lurex, interlined with non-woven polyester ‘Pellon’ and nylon net petticoats, and accessorised with a nylon faux-fur stole.

Paisley-print cotton dress by Nettie Vogues Ltd, Britain, 1948. The ‘Double Elevens’ label, introduced in 1946, indicated non-Utility garments from a manufacturer’s most expensive range. Despite this, the fabric is used carefully, with clever pleats and horizontal bands of ribbon suggesting New Look fullness. The fichu collar gives a softly rounded shoulder line.

In addition to this, fabric designers produced a vast range of original patterns for women’s and children’s clothes and even for men’s holiday shirts. While the 1950s is epitomised by overblown floral designs such as those produced by Horrockses, even that brand offered dresses printed with lobsters or eggcups, and was far from unique in offering fabrics designed by leading artists such as Eduardo Paolozzi. Many of the most famous modern artists of the day, including Picasso, Dalì, and Marc Chagall, produced distinctive painterly designs for fabrics. Even science became involved, offering up newly discovered cell-structures as inspiration for a wave of ‘atomic’ designs that not only spread across cloth, but onto furniture, wallpaper and even ceramics. There seemed no limit to the imagery to be found in textiles.

Many women made their own clothes, a necessary skill during the war and immediate post-war years. Knitting, crochet and sewing patterns were widely available. While it was possible to buy knitted garments directly, such as the haute knitwear created by Maria Luck-Szanto’s team of knitters, and ready-to-wear clothing was increasingly available, many women preferred to run up simple frocks and knitwear at home. This helped save money for necessary ready-made purchases such as shoes, coats and most men’s clothes. The skilled dressmaker on a limited budget could produce quite sophisticated garments for herself and her friends, although for those with less time (or aptitude) for dressmaking, ready-to-wear was available at many price levels and could be bought from department stores or local speciality shops. While mail-order shopping was not new, the 1950s saw a sharp increase in the number of catalogues on offer, many laden with pictures of enticingly presented garments at prices aimed towards the retailer’s target audience. Many high-end dresses, or at least, their accessories, were likely to be purchased from boutiques – a relatively new innovation in fashion retail.

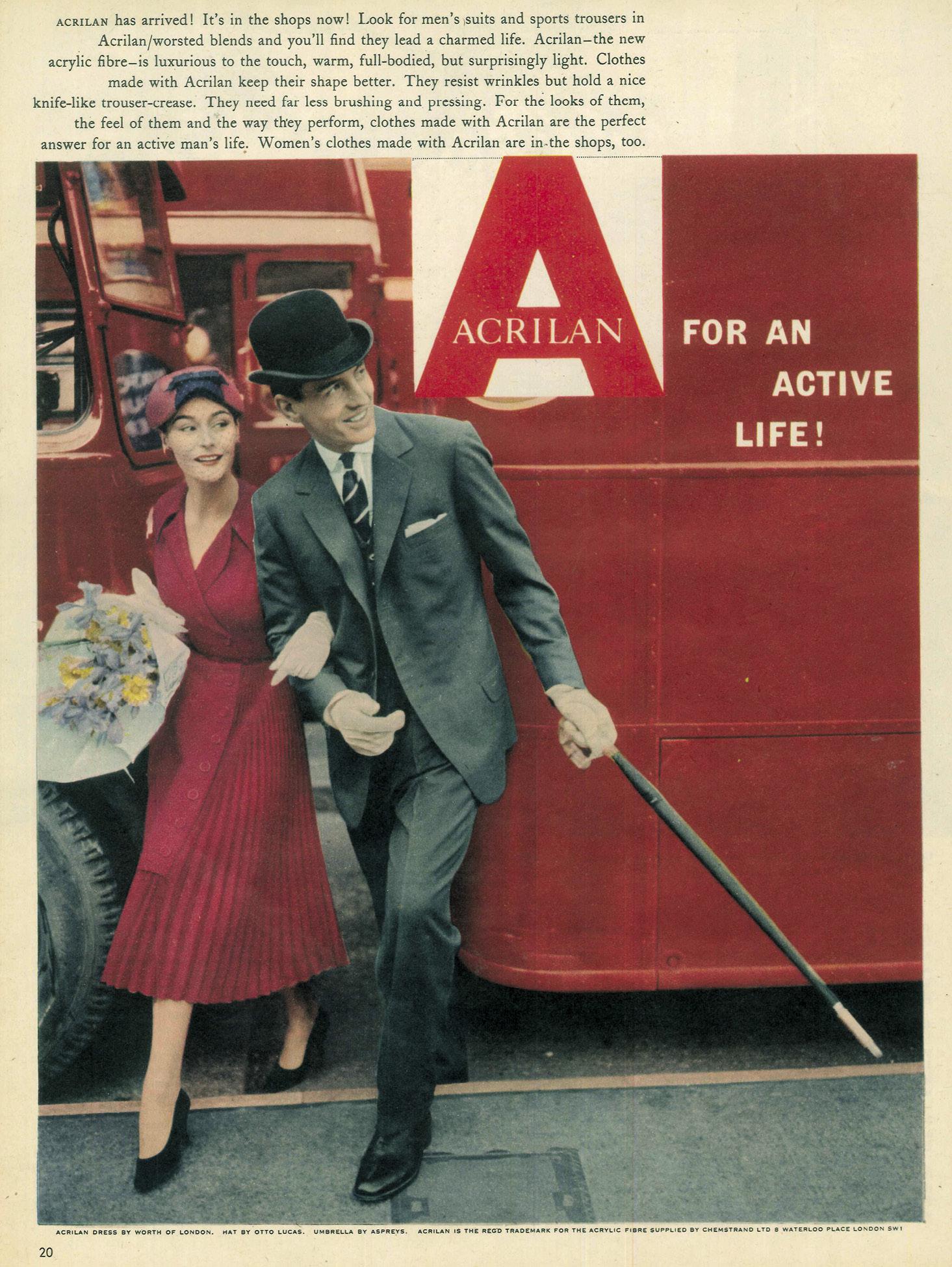

Both the woman’s dress (by Worth of London) and the man’s suit in this 1952 advertisement are made using Acrilan – a trade name for acrylic. Synthetic fabrics were widely advertised, and association with couture names such as Worth helped make them acceptable.

The boutique concept originated between the wars, with couturiers such as Elsa Schiaparelli creating striking retail spaces linked to their salons for the direct sale of perfumes and luxurious hats, gloves, shoes, costume jewellery, lingerie, dress ornaments and simple ready-to-wear. Even after Schiaparelli’s couture house closed in 1954, licensing agreements meant that Schiaparelli fragrances and merchandise including furs, hats, accessories, lingerie and some garments remained widely available through independent boutiques and department stores. Even the slightly less well-off customer might be tempted to purchase an exquisite silk rose with diamanté dewdrops from Hardy Amies, or a pair of Dior stockings.

This 1953 cocktail dress by Horrockses uses an exclusive yellow, black and white printed cotton designed by the Scottish-Italian artist Eduardo Paolozzi.

For the haute couture client compelled to undergo multiple time-consuming fittings before taking away her expensive new dresses, boutique purchases offered instant gratification. As it became clear that fewer women had the time or finances for haute couture, boutiques began stocking a wider selection of ready-to-wear, including suits and evening dresses. These helped accommodate the consumer with a smaller budget and different lifestyle to that of the haute couture client. Some of the most select department stores, such as Harrods in London, Saks Fifth Avenue in New York and Holt Renfrew in Canada, bought the rights to couture designs, which they then reproduced to order. Ready-to-wear houses also paid close attention to the latest couture designs. The London house of Frank Usher was particularly well known for high-quality line-by-line copies of couture suits and gowns, including a Dior A-line suit for 27 guineas in 1955. Although expensive, this was still a fraction of the cost of the Dior original, or even a licensed Dior London version.

Christian Dior launched his first luxury ready-to-wear line, ‘Christian Dior New York’, in 1948, following it in 1953 with ‘Christian Dior Models London’. The clothes produced under these labels, while true to the spirit of Dior, were simplified and adapted to allow for an element of mechanised production and the requirements of the American or British lifestyle. Other designers came to similar arrangements, such as R.L. Salmon Ltd’s 1957 contract that granted them exclusive rights to reproduce Jacques Heim designs for the British ready-to-wear market, using the same fabrics and trimmings as the Paris workrooms. Once made up, the garments were sold through carefully selected department stores and ‘madam shops’ – independent dress salons found in towns and cities.

The madam shops were so called because they typically catered to local ladies of means who craved high fashion but might lack the buying power for haute couture. Being able to offer an appropriate ‘Paris frock’ to the bank manager’s wife was both a coup for the proprietor and for ‘madam’, her customer, although couturiers were very strict about who was permitted to sell even their ready-to-wear garments. Madam shops often stocked home-grown labels, such as Horrockses, Susan Small and Frank Usher, or bought stock from the likes of the flamboyant designer Val St Cyr at Baroque Ltd, which from the 1920s to the early 1960s specialised in high-style fashions for madam shops. Some madam shops were actually chains, such as Chanelle (no connection to Chanel), which had branches in many cities including London, Bournemouth and Brighton.

While many home-knitters focused on simple jumpers and cardigans, the advanced knitter could produce garments such as this 1955 lilac dress with fashionably full, lace-patterned skirt and trim bodice.

Fashion was a key part of the popular press. Alongside dedicated fashion magazines such as Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar, many newspapers and general magazines dedicated sections to the latest modes, typically targeted towards their specific readership. The Lady presented accessibly written, richly illustrated articles covering the latest Paris and London couture, but also featuring good quality mid-price ready-to-wear by labels such as Susan Small and Selincourt. Their target audience was the upper-middle-class reader (and those with social aspirations) who might dream of Dior, but would be more likely to wear a Susan Small frock, particularly if presented as an acceptable alternative to Paris couture. Other, more widely distributed magazines such as Woman’s Own offered dress patterns (sometimes by famous designers such as Hardy Amies) and knitting instructions, rather than exclusively promoting garments that, more often than not, might be beyond their average reader’s budget. In 1958, the clothing retail chain Marks and Spencer inserted its first nationwide advertising feature in Woman, a widely circulated magazine with over eight million readers.

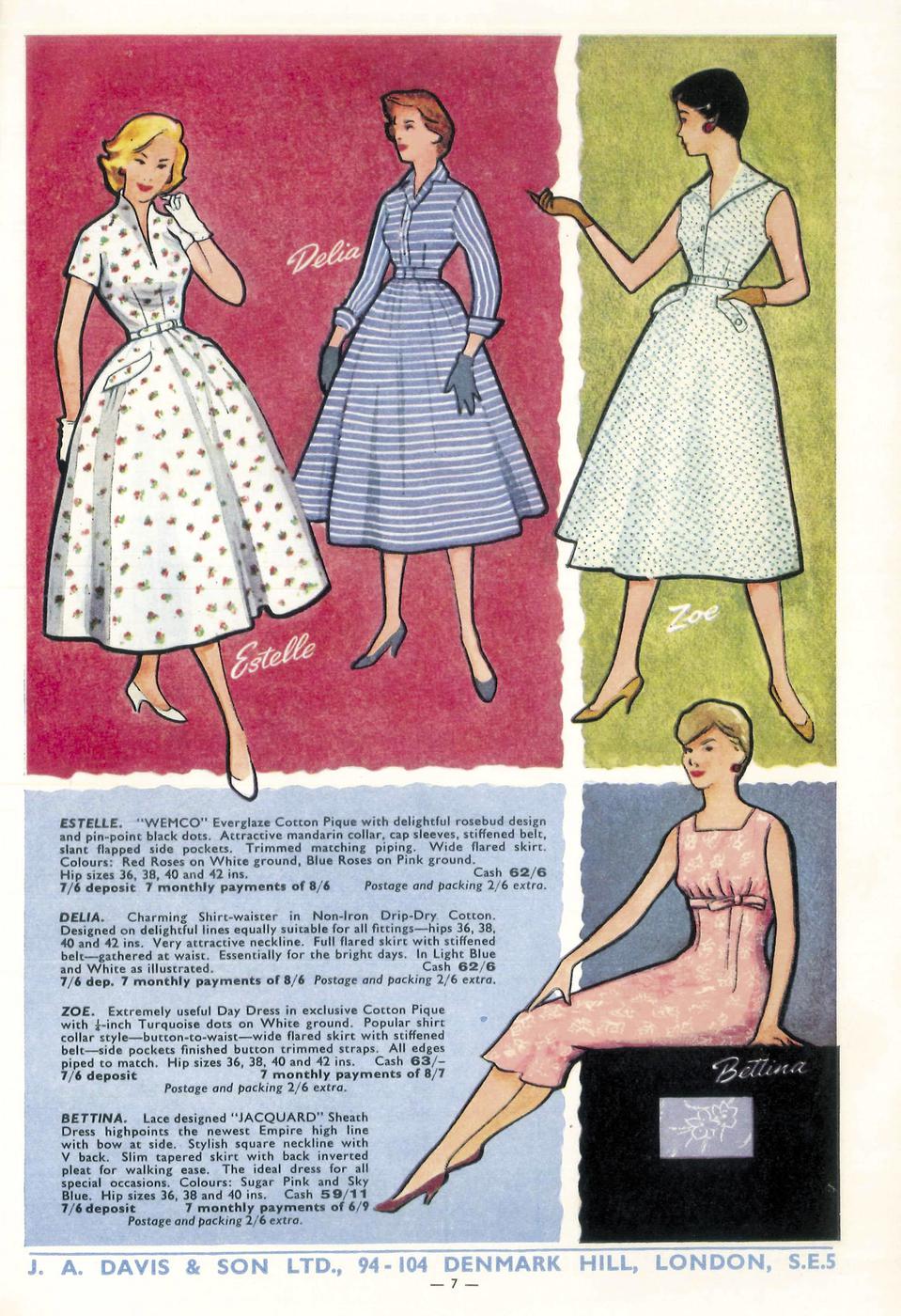

By 1958, mail-order and catalogue shopping was widespread. The London store J. A. Davis & Son Ltd offered ready-to-wear clothes in a variety of styles and designs such as these dresses in smart but reasonably conservative styles. Already quite inexpensive, they could be paid off in monthly instalments.

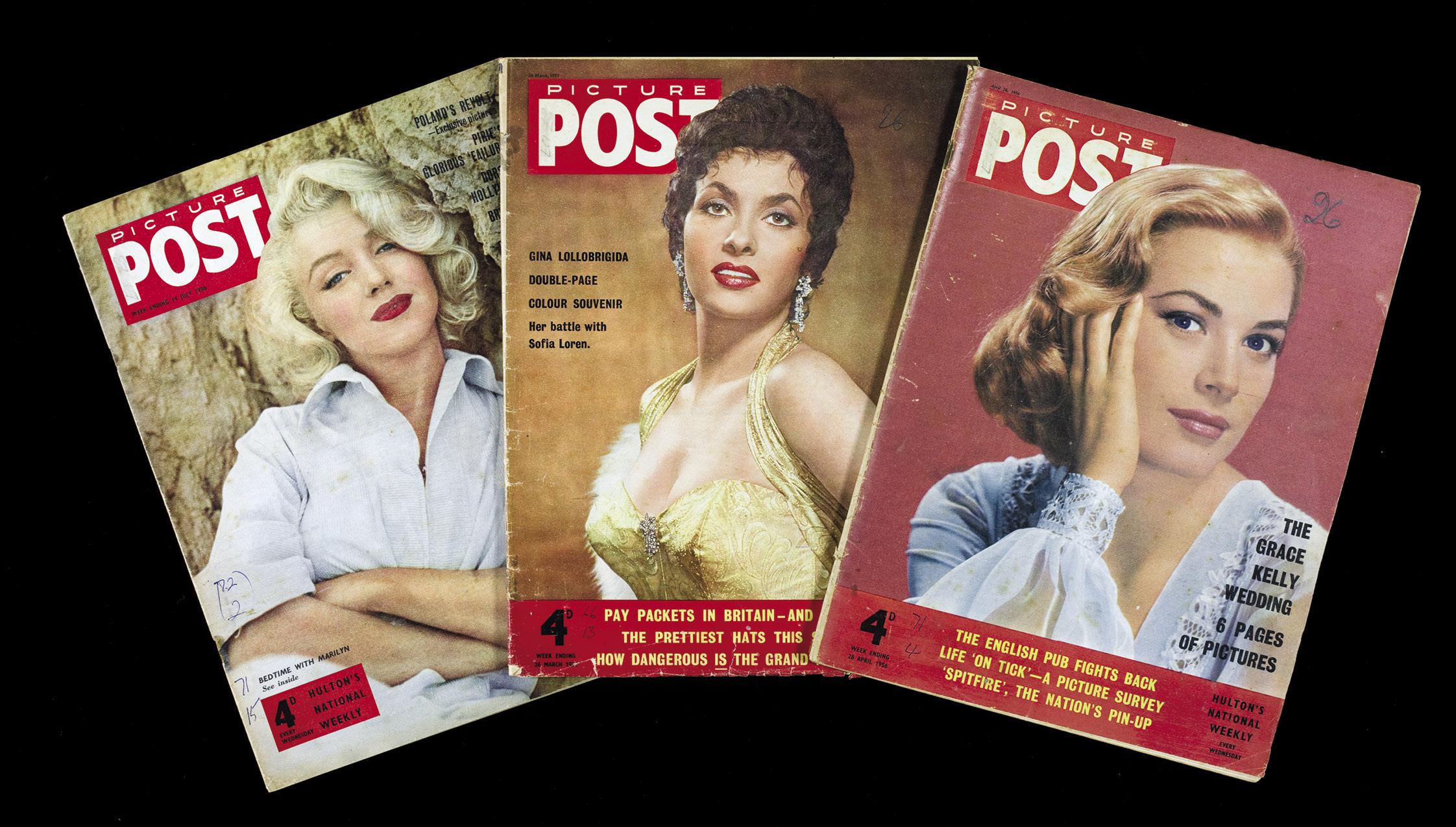

The cult of celebrity had an inestimable power upon fashion. Popular film stars demonstrated a wide range of ideals of beauty, from the gamine Audrey Hepburn to Gina Lollobrigida’s sultry voluptuousness; from Grace Kelly’s cool glamour to Marilyn Monroe’s vulnerable sexiness. The impeccably tailored elegance of Cary Grant and the rebellious leather-jacketed youth of James Dean offered two very contrasting masculine models. Despite the disdain of certain snobbish publications, which would have preferred that arbiters of style be elegant members of British high society, only the royal family’s influence on popular fashion came close to mirroring that of Hollywood.

This 1952 advertisement offers a custom-fitted, authorised copy of a Christian Dior little black dress made by the London department store Liberty’s. Liberty’s would have come to an agreement with Dior beforehand to allow them to openly reproduce this particular model.

At the time of her ascension in 1952, Queen Elizabeth II was a young, attractive 25-year-old. Her style was highly influential, not least the fact that her understated day-to-day wardrobe included neatly tailored Hardy Amies coats and suits, cardigan-and-sweater twin-sets manufactured by Pringle and off-the-peg flowered cotton frocks by Horrockses. Even when wearing an extravagant Norman Hartnell crinoline gown and magnificent jewels, the Queen managed to appear unpretentious and accessible. In October 1952, she was photographed in a black full-length Hartnell evening dress with contrasting white satin halter-neck and wide full-length lapels. Within days, cheap ready-to-wear copies of the ‘Magpie’ gown were widely available in all sorts of extraordinary colour and fabric combinations. An embarrassed Hartnell took pains to ensure that subsequent designs for royalty were much harder to duplicate. He achieved this through lavish embroidery and abundant use of fabric, ensuring that any future ready-to-wear copies of his work could only be pale imitations. The Queen’s beautiful sister, Princess Margaret, also came under scrutiny, not least because, feeling little diplomatic obligation to wear British, she proudly wore the latest Paris creations by Dior and Jean Dessès alongside home-grown Hartnell and Horrockses.

Label from a Christian Dior London suit, mid-1950s. The suit was sold through the Chanelle chain of boutiques, who added in their label.

The 1950s, with its zest for newness and freshness, laid the foundations for fashion in the second half of the twentieth century. One particularly striking aspect of the decade was the emergence of stylish options. Two ladies could walk down the street in different outfits, yet appear equally modish, be their skirts full and narrow, or one in a form-fitting sheath and the other in a loose sack dress. The idea of choice, and dressing to suit your shape and personal taste, as opposed to following one basic style regardless of whether or not it suited you, was relatively new.

Film stars demonstrated a wide range of ideals of beauty. These Picture Post covers show a tousled, friendly and approachable Marilyn Monroe, the sultrily glamorous Gina Lollobrigida, and Grace Kelly, the epitome of perfectly styled, cool elegance.