EVERYDAY FASHION: WORK AND PLEASURE

Increasing numbers of self-sufficient young women studied, held down jobs and actively pursued careers. Whatever their role, women were more visible than ever before, facing a barrage of varied opinions from the media and their peers on their role in society. One hint, not universally taken, was that a woman’s career should terminate upon marriage in favour of housekeeping and maintaining marital bliss. More universally accepted was the idea that appropriate appearance was the key to happiness, both before and after marriage. One American designer, Anne Fogarty, even wrote a 1959 book titled The Art of Being a Well Dressed Wife. Even if not explicitly ordered to dress a certain way, women were shown examples of ideal housewives or young, soon-to-be-wed secretaries declaring their desire for fitted kitchens, ultra-modern washing machines and happy home lives. These personifications of ideal womanhood dressed in a fresh, neat, feminine and modest manner that reflected their dutiful, wifely qualities.

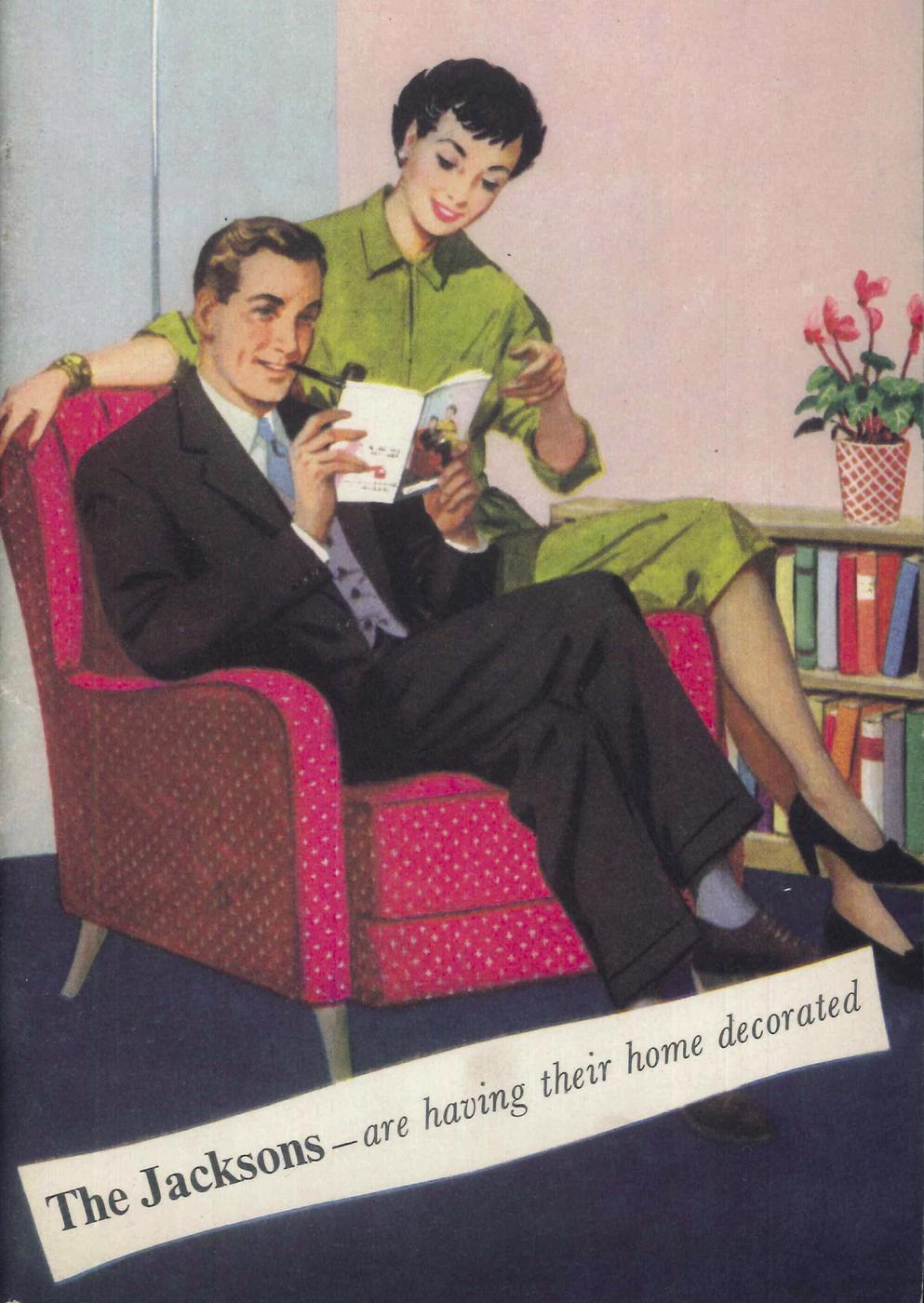

A neatly dressed couple are shown in an appropriately modern interior. Cover of a mid-1950s paint catalogue.

For the smart woman who wished to dress for the occasion, even if it was simply going shopping in town once a month, the tailored skirt suit, or tailleur, was the epitome of elegance. There was a clear distinction between town and country. The country suit came in hardy woollens or nubby tweed, usually with a practical pleated skirt for tramping around in, while the town suit declared urban sophistication with its neatly fitted jacket and slender skirt. With the smartest tailoring, emphasis was on beautiful cut and fit, with minimal detailing and trimming. An alternative was the tailored dress, similarly accessorised with gloves, hat and handbag. The lean lines of the town suit were elegantly complemented by long-handled, tightly rolled umbrellas. From about 1954, suits began taking on a straighter, less-fitted silhouette, although defined waists and peplums briefly reappeared in 1957. By the end of the decade, the fashionable suit had a straight-cut jacket and slim skirt, sometimes part of a coordinating dress. After Coco Chanel’s comeback in 1954, her deceptively simple cardigan suits swiftly became classics. Manufacturers such as Wallis offered authorised reproduction ‘Chanel suits’ to their customers. Some extremely chic tailor-mades had coordinating stoles and scarves, although many women favoured coats.

This elegant town suit was presented in a fashion show in Leipzig in 1954. The fitted jacket and slender pencil skirt, worn with gloves, peep-toe slingback sandals, small hat and plaid-lined overcoat, show this classic early 1950s look at its most accessible.

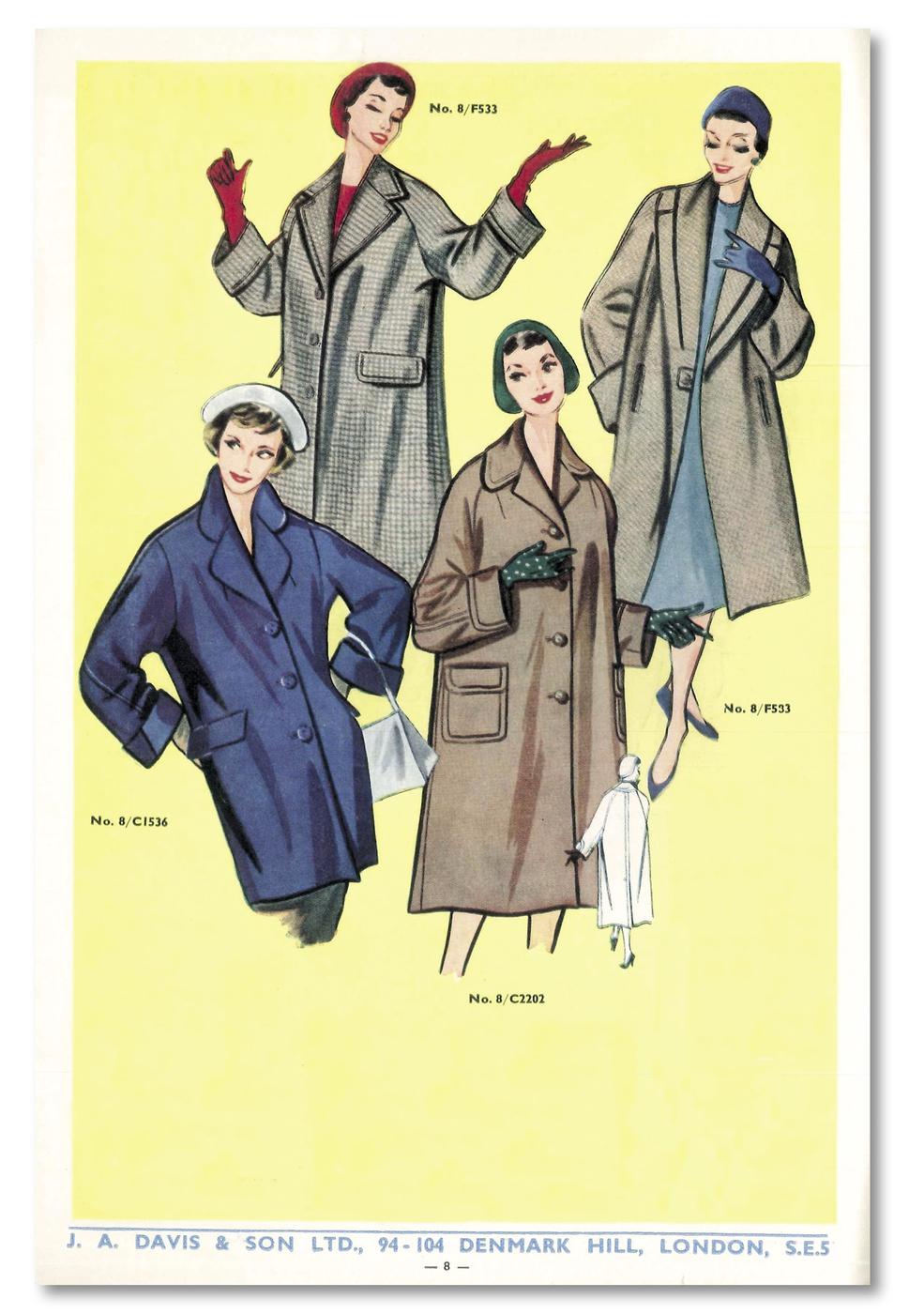

The coat was a universal wardrobe staple, and a key investment for the woman on a tight clothing budget. The sensible shopper bought the smartest, most practical ‘good’ coat she could afford. Although rarely the most fashionable of garments, the advantage of the three-quarter-length coat buttoned securely down the front in sturdy wool or wool-blend fabric was that, with smart shoes, handbag, scarf and hat, its wearer looked neatly respectable even if the dress concealed underneath was a little shabby.

This vibrant ‘Chanel’ suit was made by the ready-to-wear firm of Wallis in c.1960. Although made in synthetic blend fabrics, it is immediately recognisable as a version of Coco Chanel’s classic design first introduced in 1954. Wallis’s agreement with the Paris house allowed them to make and market such obvious copies.

Conservatively styled coats for the 1958 mail-order market. The models are shown with smart hats, handbags and gloves (including a green and white polka dot pair), suggesting styling options to the customer.

More fashionable coats came in a wide variety of styles, lengths and materials, frequently following the silhouette of the dress beneath. In the early 1950s, many coats had trim bodices, flaring out into full skirts, often counterbalanced by large shawl or portrait collars. As dresses became slimmer, so did the coats. A particularly popular style was the swing coat, hanging from the shoulders and flaring out to accommodate both slim and fuller skirts. The clutch coat, a variation on this style, lacked fastenings, though Queen Elizabeth herself quickly spotted its impracticability, asking how she was supposed to shake hands and accept bouquets while casually holding her coat closed. Loose coats with abbreviated sleeves were particularly flattering to older women. The Spanish couturier Cristóbal Balenciaga, highly acclaimed for his austere, flawlessly proportioned designs for mature women, famously admired the seven-eighths length or ‘bracelet’ sleeve, seen on suit jackets and dresses as well as coats. By focusing attention on the wrist and hand, bracelet sleeves elongated short arms and drew attention from a less-than-perfect figure. Gloves covered the hand and exposed forearm, which, when seen gracefully emerging from an elegantly outsized cocoon coat, gave a sense of overall slimness, as did a glimpse of well-shod feet and nicely stockinged lower legs beneath the hem.

Two wild mink clutch coats from 1955. Although made from luxurious fur, the mid-calf length, loose flaring cut and bracelet length sleeves also appeared in cloth coats.

Many younger women, especially those who drove or travelled regularly, found short jackets and ‘car coats’ much more suited to their active lifestyles. Leather jackets, typically cut in simple, boxy silhouettes, were thoroughly young, modern, informal options.

This cherry-red leather jacket was purchased in 1951 for £12 – at the time an extravagant purchase. Its short length and simple styling made it a versatile garment with a long wardrobe life.

Ever since it first emerged as an everyday staple in the late nineteenth century, the concept of the blouse-and-skirt ensemble had never gone out of style. With a tailored skirt, it was practically a uniform for many working women. During the 1950s, skirts fell between knee and mid-calf, and could be either lean or full. The use of separates was strong, many women appreciating the chameleon qualities of basic wardrobe staples. While the garments themselves were quite straightforward in cut, the way they were worn and their fabrics set the mood. The conservative older lady and the lively young woman might both wear similar skirts, but where the former wore a modest blouse and demure cardigan, the other might wear a tight sweater.

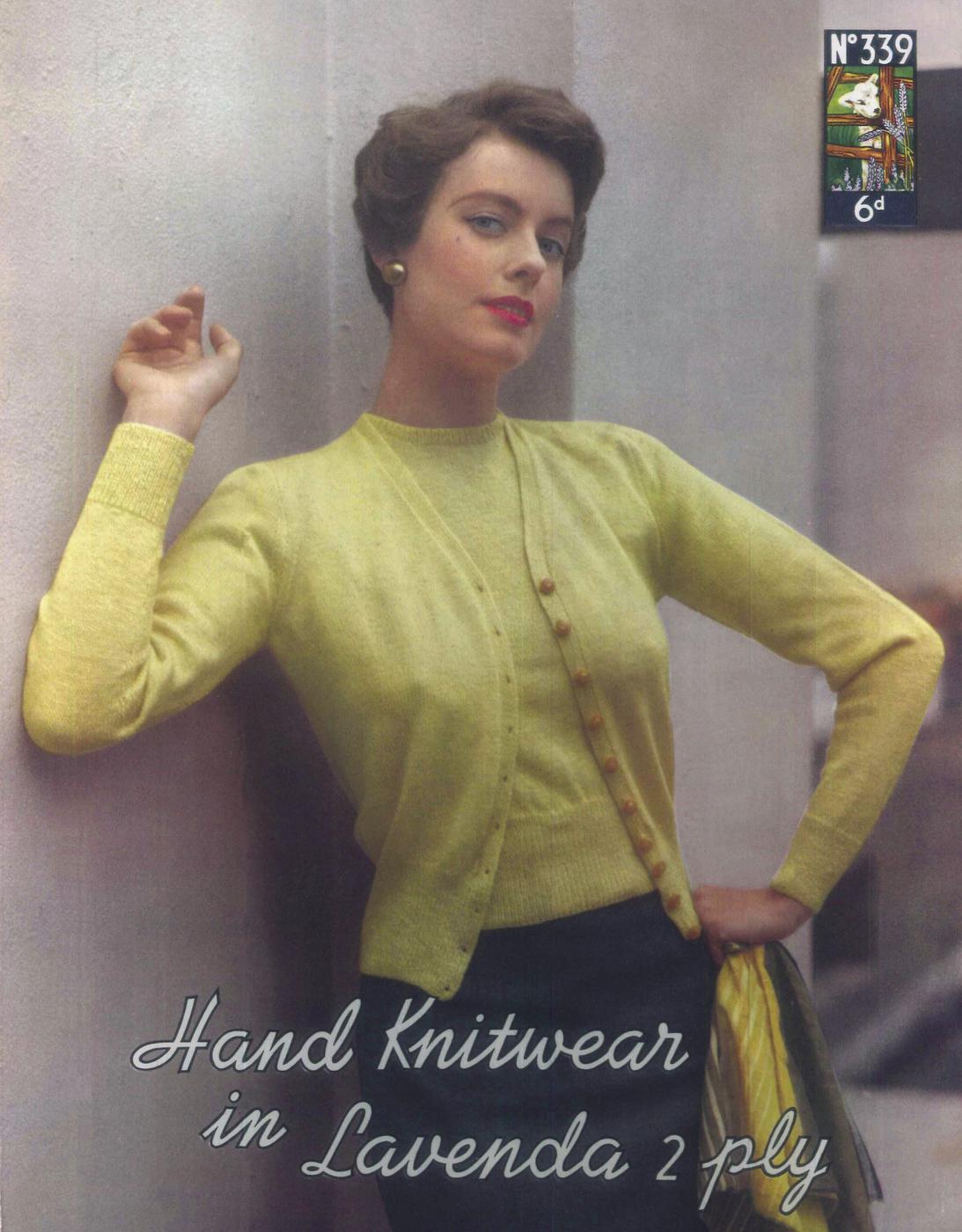

The twinset was widely worn by women and young girls. While Queen Elizabeth had her cashmere twinsets from the Scottish company Pringle, many women knitted their own, making it a truly accessible fashion.

By the 1950s, it was increasingly acceptable for skirts to be replaced with slacks for active young women. They would throw a short jacket over their trousers, maybe tie a headscarf, and run off to see about their day-to-day business. However, for anything other than the most informal occasions, skirts and dresses were considered essential. Full skirts in lightweight cotton were particularly popular summer-wear, coming in a vast range of colourful novelty prints and lively patterns. Heavier cotton and wool skirts served for winter. Among younger women there was a craze for appliquéd and embellished circular felt or corduroy skirts. The American designer Juli Lynne Charlot is credited with inventing these so-called ‘poodle skirts’, named for a particularly popular motif. However, as with novelty prints, anything could appear on these skirts, from slogans to music notes to telephones, or even racial stereotypes which now appear shockingly insensitive to modern eyes.

Short coats and slacks were undeniably practical. This 1958 advertisement shows a woman dressed to ride her Vespa scooter in a fuchsia felt car coat, black trousers and a headscarf. Crash helmets only became compulsory in the UK in 1976.

During the second half of the 1950s, the fashionable silhouette underwent a number of rapid changes, as if reacting strongly against the cinched waist of the late 1940s and early 1950s. First came the straight-cut cardigan suits of 1954, associated with Chanel’s comeback collection, but introduced simultaneously by Dior and Balenciaga, emphasising a natural silhouette where the sides of the jacket or bodice hung almost flush with the natural widest point of the hips. Dior called his version of this the ‘H-line’, following it up the next year with the ‘A-line’, featuring high busts, from which jacket bodies and skirts flared out like the letter A. This was then followed by the slender skirted ‘Y-line,’ with wide collars, stoles and shoulder lines, echoing the letter Y. The A-line proved influential, its name becoming a standard term for skirts and dresses that echoed the letter. In 1958, the A-line was exaggerated even further to create nearly conical trapeze-line dresses which hung from the shoulder. Between 1955 and 1958, form-fitting sheaths and high-waisted chemise dresses also came into fashion. The latter were popular, but had to be cut with closely tapered hems to avoid being mistaken for nightgowns. The narrow hem was also necessary for the loose sack dress, as promoted by Balenciaga and the Italian designers. On Balenciaga’s ideal woman, in all her arrogant hauteur and confidence, the consciously unfitted sack was elegant, skimming over and camouflaging figure defects, showcasing superbly stockinged legs and neat ankles, and elegantly gloved arms. However, many men hated the sack dress, preferring to see clearly indicated busts and waists rather than use their imagination. The style was often criticised and called ugly and unflattering. Propaganda against such garments included implying that rather than hinting at concealed shapeliness, they suggested the wearer had gained weight – or that she was pregnant. Such a paradox was exploited by the young Lady Antonia Fraser at Ascot in 1958, when her very simple white trapeze dress by Kiki Byrne successfully hid her pregnancy from the assembled photographers.

Although these appliquéd wool felt skirts were popularly called ‘poodle skirts’, many alternative motifs were used. This example, by Juli Lynne Charlot, the designer credited with inventing the original poodle skirt, features a skiing theme.

The poodle skirt swiftly spread around the world. This 1957 Japanese teenager models a design appliquéd with caricatures of black people. Although now appearing (at best) highly insensitive to modern eyes, racially themed designs (including Vladimir Tretchikoff’s popular ‘Chinese Girl’ print) were a widespread decorative theme of the 1950s.

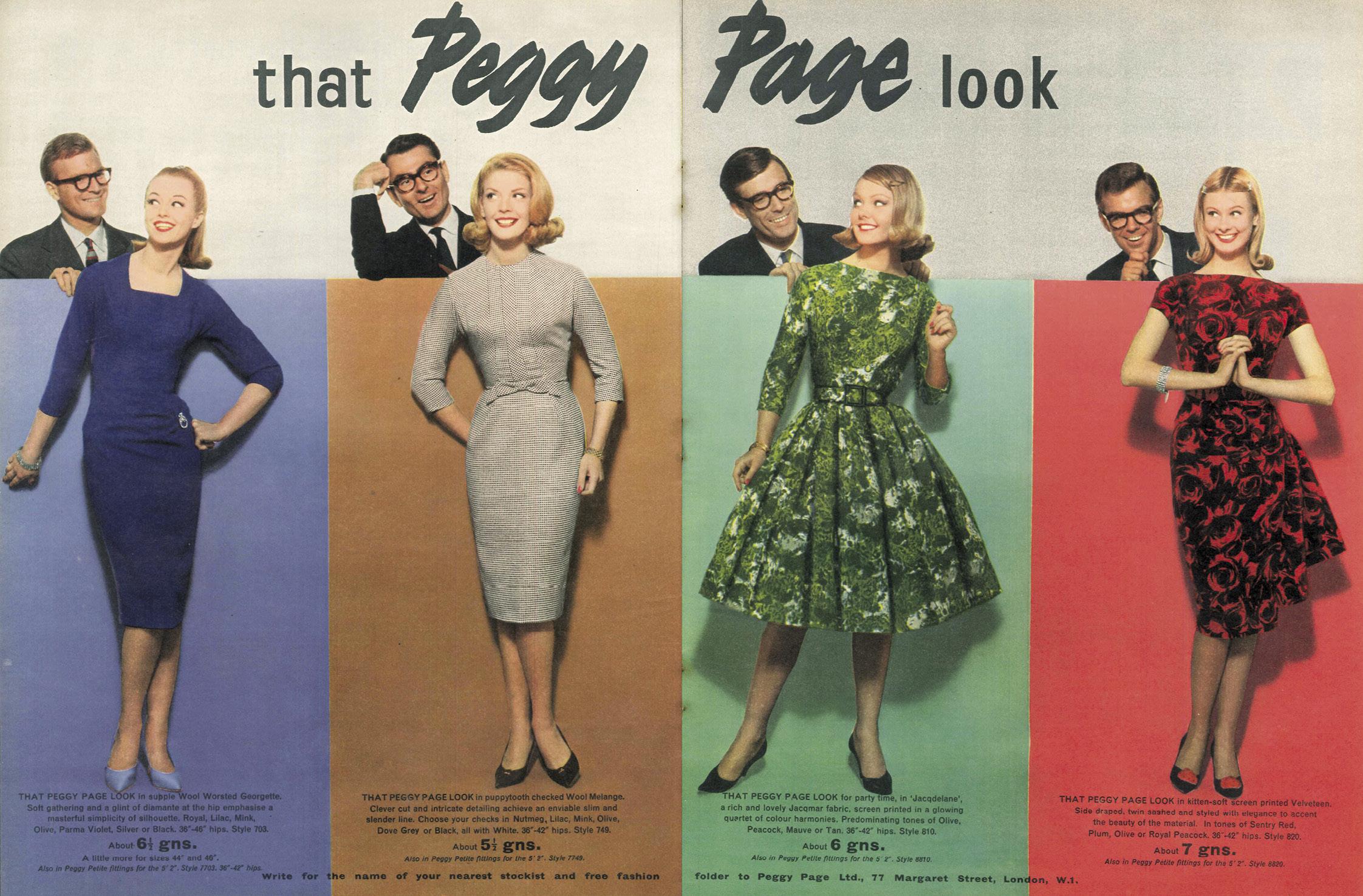

By the late 1950s, women’s fashions no longer followed a single silhouette. Full skirts and slender form-fitting silhouettes were both equally chic, according to this 1960 advertisement for Peggy Page ready-to-wear fashions.

By 1959, the fashionable silhouette was natural, with bust, waist and hips free of exaggeration or suppression. Alison Adburgham suggested this was only a normal reaction to there having been too many quick-fire changes in too few years. Certainly, between 1954 and 1959, fashionable silhouettes had bounced from loose sacks to fitted sheaths to kicky trapezes, while hems and waists constantly rose and fell. One thing that had remained consistent throughout was that all these diverse styles had been immaculately accessorised.

The dress on the cover of this 1958 French fashion magazine was designed by Yves Saint Laurent for Ligne Trapèze, his first solo collection for the House of Dior. As so often happened following a new Dior collection, other designers and manufacturers then produced their own versions of the latest look.

Despite the general admiration for a superb-quality, understated leather handbag, neat gloves and a modest, perfectly proportioned hat, a broad sense of humour often emerged in 1950s accessories. As with the novelty print and the poodle skirt, subtlety did not preclude outright whimsy. Many milliners offered ‘fun hats’ with unexpected, even comical trims, combining chic with crazy. Handbags, too, showed this quirky taste, mainly in summer wear. The day-to-day holdall might be a capacious straw affair with amusing appliquéd decoration on the side, or a slightly more formal bag might have an unexpected form, suggesting a baguette or a beehive. One American idea was that of the hard box bag, either in painted or collaged wood, or ultra-modern, often clear, Lucite plastic. In 1959, Anne Fogarty warned against bags ‘heavily encrusted with flowers, jewels, buttons, bows, poodles and perhaps a replica of Sherwood Forest’; and also criticised transparent purses.

The sack dress was taken up by designers around the world. This extremely elegant 1958 design was made by the American couturier Norman Norell.

One popular American novelty was the Lucite plastic handbag. These bags were made in a wide range of shapes, colours and sizes. Despite unease at revealing your bag’s contents, clear ones were popular.

Plastic was an exciting, modern material for accessories, from hats to shoes. Although more typically associated with the 1960s, high-quality plastic garments were known too. In 1956, a Mayfair salon launched the leather-effect vinyl ‘Scooter Coat,’ available in pure white or pastel colours, with welded seams. Made by the old Lancashire firm Mandleberg’s (renowned for having perfected odour-free waterproof fabrics in the nineteenth century), the Scooter Coat was an early instance of a fashionable plastic garment. By 1958, retailers were offering plastic aprons, raincoats and even underwear, though these were generally functional rather than modish. Plastic was also widely used for eyewear. Alison Adburgham wrote in The Guardian in 1955:

The sunglasses: all those unbelievable lunacies in the opticians’ windows are now on the faces of the passers-by. The upswept frame, elfin or satanic, the narrow window-frame oblongs, the eccentric polygonals, frames star spangled or gilt fandangled, petalled like sunflowers or shaped as swans; people are actually wearing these things in all seriousness in the streets.

These late 1950s American ‘Springolator’ mules use plastic imaginatively. The vamps feature dried flowers and Lurex threads laminated between two layers of vinyl, while the heels are Lucite beads. The ‘Springolator’ patent construction used sprung elastic to fit the inner sole securely to the foot. The pale pink plastic sunglasses still have their original price tag.

The idea that eyewear could be fun as well as functional was relatively new. If spectacles were necessary, then the wearer was encouraged to treat them as an accessory to be casually taken on and off at whim and toyed with, rather than as a permanent facial fixture. Many of the more eccentric sunglasses designs were probably reserved for vacationing, along with the wicker bags shaped like poodles or umbrellas and the more bizarrely patterned novelty print sundresses and circle skirts. Many young women wore trousers on the beach, usually slim ‘clam-diggers’ terminating just below the knee and worn with sleeveless tie-fronted blouses and short, loose lightweight jackets. Frank Usher offered a ready-to-wear resort ensemble of clam-diggers, tight fitting sun-top and separate full skirt, all in the same coordinating fabric print. Skirts could also be worn over swimsuits, though many women carried bathing costumes separately.

This printed cotton sundress was probably home-made in the late 1950s. The lively novelty print, featuring cat’s eye sunglasses, beach hats and magazines, instantly evokes a holiday mood. It has a matching bolero jacket (not shown).

A mid-1950s advertisement for beachwear by the American designer Greta Plattry. All garments – sundress, swimsuit, and beach-jacket – are made from the same printed cotton to enable mix-and-match dressing.

These late 1950s ‘pin-up’ postcards show fashionable swimwear that would also have been quite normal beachwear. The bikinis are made from novelty print cottons depicting fish and comic illustrations.

The 1930s invention of the two-piece bra-and-knickers bathing costume became universally known as the bikini in this decade. In May 1946, the Parisian couturier Jacques Heim launched a costume called ‘Atome’, advertised as the ‘smallest costume in the world’, though its high-waisted bottoms still concealed the navel. Two months later in Paris, Louis Réard launched with great fanfare his own ‘smaller than the smallest costume’ design. So scandalous were its four skimpy triangles of newsprint fabric, held together with strings, that only a nude dancer from the Casino de Paris was prepared to model it for the launch. Named after the Bikini atoll where atomic bomb tests had happened a few days earlier, the name stuck. With slightly more substantial tops and bottoms, so too did the navel-baring style. The ‘itsy bitsy teeny weeny’ versions of the bikini were only really worn by the young and confident, and by pin-ups and glamour girls.

Alternative, more widely worn swimwear styles included classic one-piece costumes such as the rather more universally flattering ‘bloomer suit,’ with puffy pants, and, occasionally, skirt ruffles. Whether one- or two-piece, swimsuit fabrics remained consistent: printed and/or polished cottons, often with elastic shirring; crisp waterproofed taffetas with boned seams; or stretchy jerseys and lastex-blend satins.