FORMAL WEAR: GOING TO THE BALL

Occasion wear was a big part of 1950s fashion. Whatever one’s budget, it was important to look as well turned out as possible when invited as a guest to a wedding, dance or party. One increasingly popular social event was the cocktail party, usually held in the early evening. The cocktail dress bridged the gap between afternoon and evening wear. Typically made in lengths and styles appropriate for dressy afternoon or late daywear, it tended to use materials and decoration associated with evening wear. A flowered afternoon dress with a low neckline and short sleeves might have a solid coloured coat lined with the dress material, while a satin cocktail dress could have a matching cocktail coat. Such coats were appropriate for formal afternoon occasions, later being removed for the cocktail party. Guests might also appear in full evening dress en route to a more formal event, just as other attendees might drop in after attending an afternoon event. Although far from a brand-new innovation, the idea of clothes that transitioned with ease from day to evening increasingly took hold in this decade. For example, under her suit jacket, the working woman might wear a dressy blouse or short-sleeved top suitable for an after-work date. Gauzy nylon or translucent chiffon were popular fabrics for such tops, which, like the equivalent dresses, were sometimes called ‘sheers’, and were always worn over an under-slip or camisole.

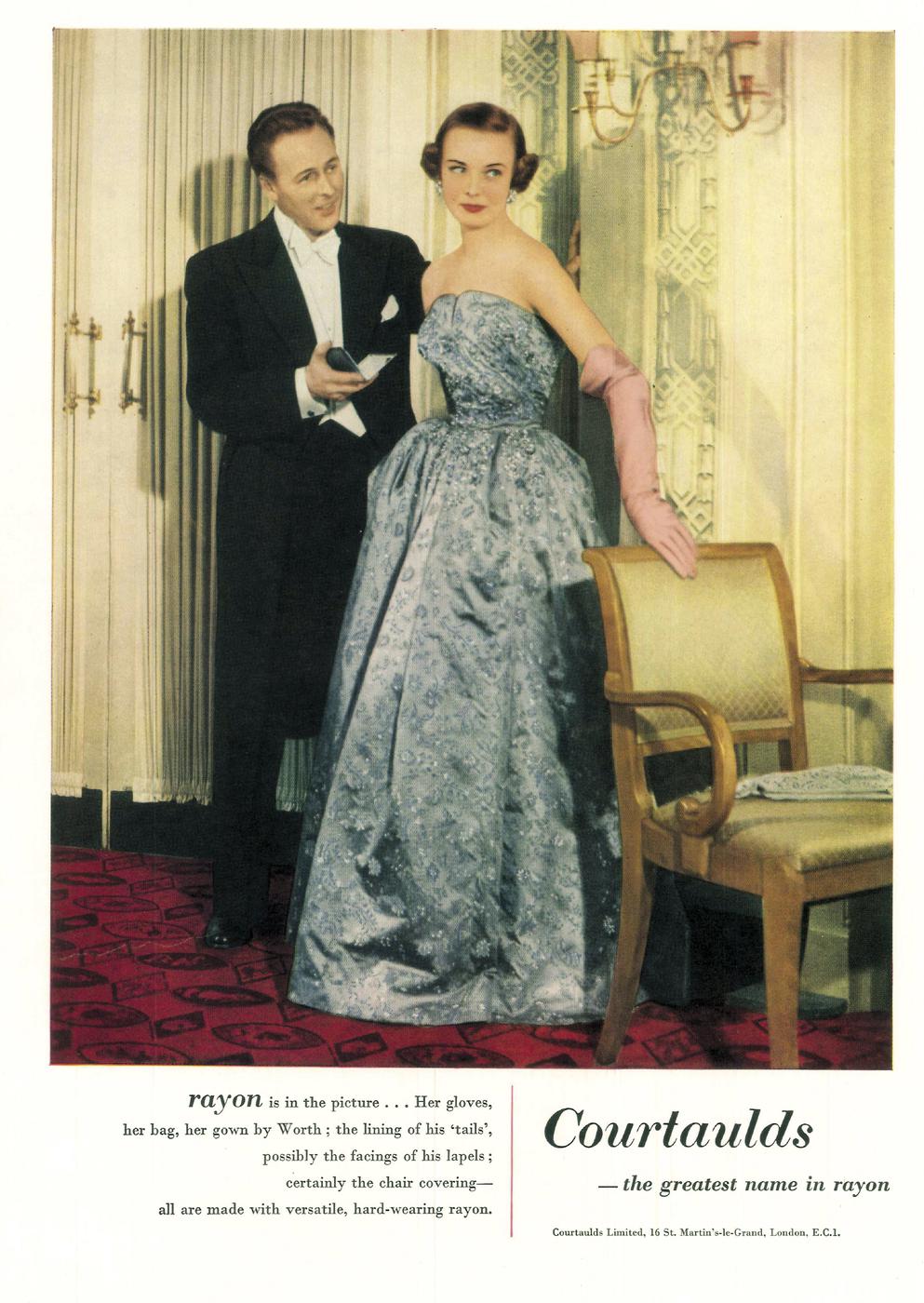

The strapless ballgown in sumptuous fabric with long gloves was a classic 1950s evening look. This 1952 design by Worth was made to promote rayon as a new fabric for evening wear, both for her gown and gloves and for the details on his evening suit. Even the chair features rayon upholstery.

The practical advantage of the cocktail or afternoon coat was that it offered warmth and coverage for cooler days and evenings. Particularly towards the end of the decade, the shoulder stole in coordinated fabric was a stylish option, and not just for evening dresses. Real fur wraps, sometimes lined to match the dress, were luxurious and highly desirable. Due to fur-farming, formerly uncommon furs such as mink and silver fox were increasingly accessible and, if not widely affordable, were at least less expensive – particularly in the form of small accessories, such as neck scarves or removable collars designed to be tacked to a coat, sweater or suit jacket. By the end of 1958, a significant drop in the purchase tax on small furs enabled one Knightsbridge furrier to offer six-guinea mink scarves. Even tinier scraps of fur were incorporated into brooches, earrings and shoe-clips. One particularly amusing novelty was the mink garter, as worn by Wallis, Duchess of Windsor. However, wealthy women demanded rarity and luxurious exclusivity, represented by wild mink, or big cat furs such as leopard, which could not be farmed. The demand for spotted cat led to a wide market for imitations, both in stencilled mouton and calfskin, and in faux fur. Partly due to the expense of the real thing, and partly due to growing consciousness of animal cruelty, imitation fur became increasingly popular. By 1959, with brand names such as ‘Furleen’, Astraka was one of the leading manufacturers of nylon fake fur. An extremely widely worn style of fur coat at the time was the straight-cut three-quarter-length jacket in real (or mock) Persian lamb with a contrasting mink collar.

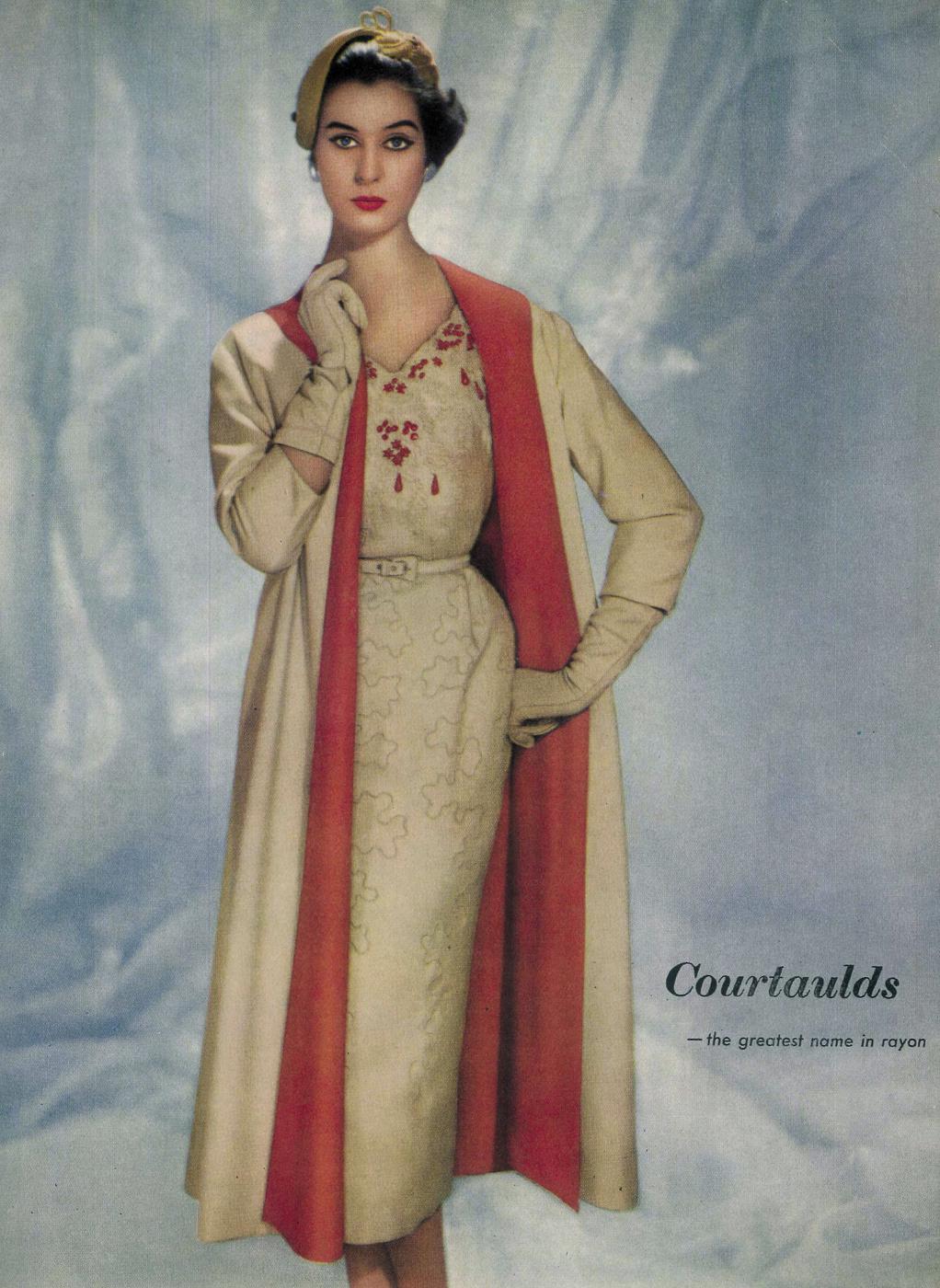

This elegant coat and dress ensemble by Roecliff & Chapman is designed to work both as a cocktail dress and as a very dressy afternoon outfit. The ruby lining of the coat picks up the beaded accents on the dress.

For formal 1950s evening wear, the strapless gown, held up by a combination of tightness and boning, was a staple look. A relatively new invention, one of its first high-profile wearers was the American singer-actress Libby Holman, who wore strapless gowns as early as 1932. The American couturier Mainbocher, then Paris-based, is sometimes credited with inventing them two years later in 1934. Through the 1930s and 1940s, couturiers such as Charles James explored the potential of this new style. Dresses without visible means of suspension attracted attention, and not a little anticipation. However, the film Gilda (1946), with Rita Hayworth’s sinuous gyrations in a sliver of black satin, showed a wider audience that well-fitted strapless gowns need not threaten involuntary exposure. Post-war designers, including Dior, swiftly understood the power of the strapless bodice. From a design perspective its briefness was the ideal counterbalance to extravagantly sweeping skirts, combining modernity, Hollywood glamour, Parisian elegance and sex appeal. By begging the question as to how the dress stayed put, it drew attention to the technical skill involved in its design and construction. However, the look attracted criticism from a vocal moral minority outraged at its perceived immodesty. In 1952, for one of her first official portraits as Queen, Elizabeth wore a strapless dress in black pleated taffeta. Although a relatively atypical style for her, it effectively conferred the royal stamp of approval. Many purchasers insisted on shoulder straps being added to their new gowns, although such details were more psychological than functional. Some dresses had removable straps, or matching jackets, stoles and boleros for extra coverage.

This 1950s costume jewellery brooch incorporates a small piece of fur to offer that special ‘touch of mink’.

While coats and stoles of rare fur were very much an expensive luxury, small fur accessories such as this ocelot neck scarf were more accessible. This is real spotted‑cat fur, but stencilled mouton and faux‑fur versions were widely available.

Although rarely absolutely convincing, faux fur was widely available by the end of the decade. This c.1960 stole is made from cream nylon.

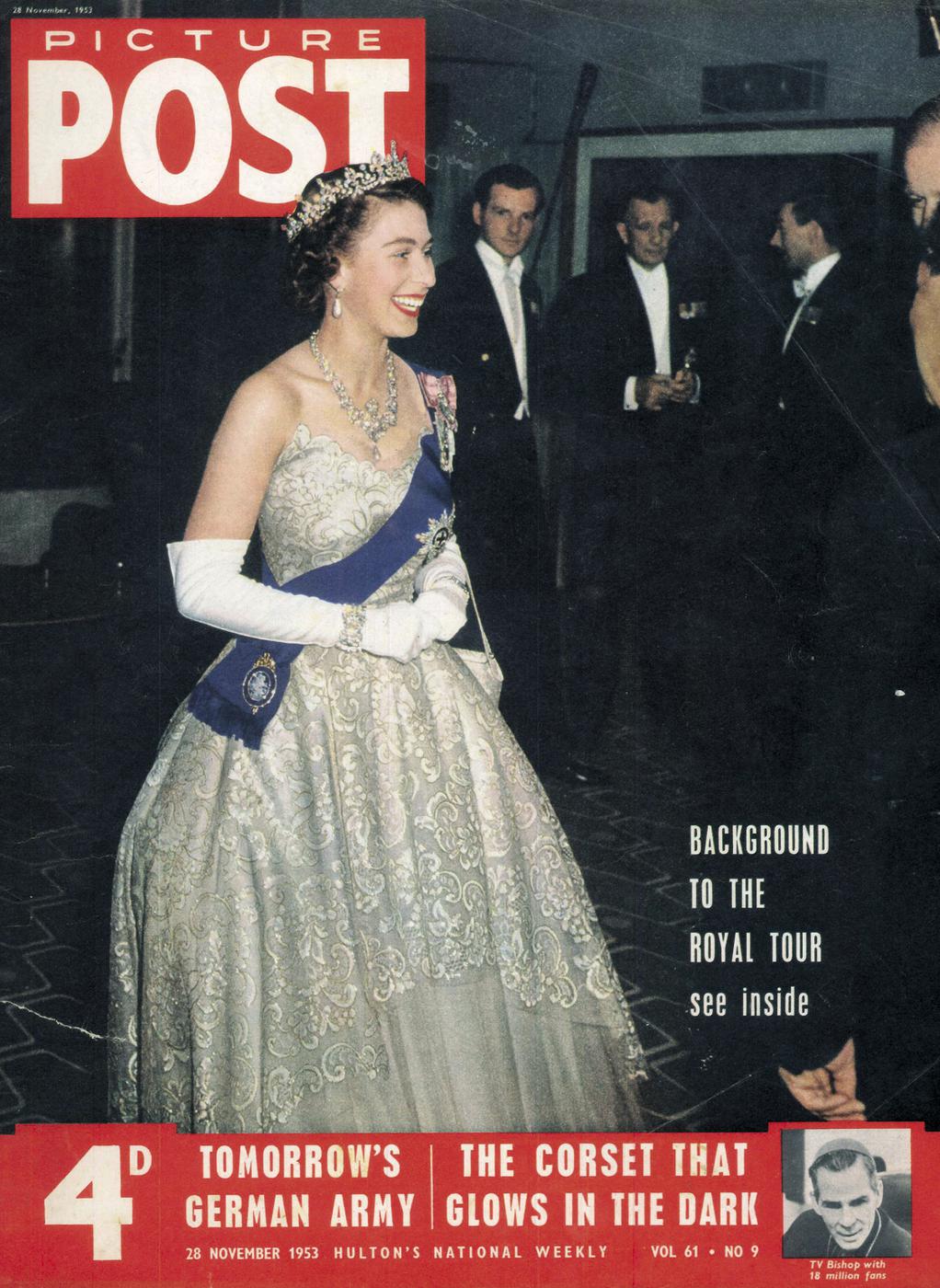

While the form-fitting sheath dress enjoyed enduring popularity in its own right, the crinoline held sway in a wide variety of forms and materials. Full skirts dominated evening gowns for much of the decade. On a number of levels, this was not altogether surprising. Evening wear often represented a dramatic departure from everyday wear, both in its fabrics and cut. After the skimpy skirts enforced by 1940s fabric shortages, flamboyantly sweeping skirts were an ultra-romantic, feminine alternative. In addition, the Queen, her mother and her sister were often seen attending grand occasions in splendid Norman Hartnell crinoline gowns. While travelling to an event, ballgowns – whether full-skirted or not – might require the protection of voluminous opera coats and cloaks in sumptuous fabrics. With new waterproofing techniques being applied to satins and velvet, a luxurious coat need not suffer unduly from an unexpected shower. Although towards the end of the decade some journalists reported seeing evening raincoats with mink linings or jewelled buttons, others noted that these ‘novelties’ were actually shiny satin or taffeta evening coats cut in a slim, tailored manner, again echoing the lines of the gowns beneath.

By choosing strapless gowns, the young Queen effectively marked the style with the stamp of royal approval. This gold-embroidered tulle gown was worn for a 1953 royal tour.

Towards the end of the decade, evening gowns became cleaner in silhouette. Although still admired, the full skirt was increasingly seen as a young style, and narrower designs were thought more appropriate for mature women. The Queen Mother was a glorious exception in her trademark Hartnell crinolines that she had worn since the 1930s. Even the Queen increasingly wore slimmer, more streamlined gowns into her early thirties. Bouffant skirts remained popular for shorter dresses and dance dresses, along with striking silhouettes such as the ‘bubble skirt’, where skirt fullness was caught into a narrow hem band. Elegant full-length formal gowns tended towards a slenderer line with slight fullness at the waist, or fanning out from a trim bodice and slim hips into a flaring hem. Décolleté necklines remained popular, but the sleeveless or short-sleeved, scoop-necked ‘shell’ bodice became more typical. Gowns made in two contrasting parts were popular, such as bodices with dense embroidery or heavy lace paired with solid-coloured, unadorned skirts in textured wild silk or glossy satin. Alternatively, a plain velvet or satin bodice might be teamed with a patterned skirt. When made as separates, they could be mixed and matched for a variety of looks. Shell tops could even accompany slim-fitting velvet or satin trousers for informal at-home entertaining. Along similar lines was the idea, often attributed to Mainbocher, of the embellished evening sweater that combined glamour with practicality and relaxed informality.

Mermaid gowns – a form-fitting sheath blossoming out into fullness at around knee height – offered the best of both worlds. The style, however, was probably too dramatic to be widely worn.

A key manufacturing spot for beaded and embroidered knitwear and other garments made for worldwide export was the British Crown Colony of Hong Kong, renowned for its tailoring and dressmaking. Excellent quality Chinese silk and wool fabrics were easily accessible, and cheap labour enabled bulk production of beaded evening bags and accessories and sequinned evening tops and dresses in silk-lined wool knit or lace, which moulded to the figure for a perfectly fitting effect. Several higher-end ready-to-wear labels took advantage of Hong Kong manufacturing to offer superior finishes and decoration on their garments for a fraction of couture prices. One technique, where instead of a lining the internal seams in a garment were individually bound with silk, became known as ‘Hong Kong finish’. Many expatriates and international travellers, male and female alike, patronised Hong Kong tailors and dressmakers for top-quality custom-fitted suits and outfits at bargain prices.

By 1960, when the California brand advertised these Bri-nylon chiffon and organza evening dresses, short evening dresses were just as acceptable an option as obviously synthetic materials. The little black dress has a pencil-slim underskirt under its bouffant overskirt.

By the end of the decade, trousers had become a valid option for informal entertaining and casual evening wear. This advertisement for Londonus slacks shows printed velvet trousers worn with luscious silk blouses.

Along with the idea of evening knitwear, fabrics associated with daywear were an increasingly viable option. Throughout the 1950s, the Cotton Board regularly held fashion shows showing London and Paris couture gowns made up in British-made cotton fabrics. Alongside day frocks, designers including Jean Dessès, Worth and Victor Steibel produced cotton gowns for the most formal occasions. Horrockses also used their signature floral cottons to make beautiful summer evening dresses with lavishly full skirts, which, as with their day dresses, were washable and wore well, combining extravagance with practicality. Like their fellow ready-to-wear companies, Horrockses also produced evening wear in more traditional fabrics. After the war, the highest-quality artificial fabrics were increasingly seen as a serious rival to natural fibres. The massive surge in popularity of synthetic fabrics even reached the world of haute couture. While a few avant-garde couturiers such as Elsa Schiaparelli had openly embraced synthetics since the 1930s, couture was still associated largely with the finest silks and woollens, with man-made fibres used, if at all, for interlinings and garment structures. In 1954, Dior made up one of his most magnificent gowns in cellulose acetate satin manufactured by the British textile company Sekers as a special commission for Lady Sekers, and by 1957, his ‘Free Line’ collection included a spotted nylon net ballgown called ‘Belgique’.

The pink cocktail dress and coat were manufactured by Elka Couture, a British ready-to-wear company. Garments could be partially made up in Britain and then sent to Hong Kong for hand-finishing and beading, to keep prices low and quality high. The richly beaded knitted evening shell was made in Hong Kong for export to the Western market.