UNDERWEAR: THINGS SEEN AND UNSEEN

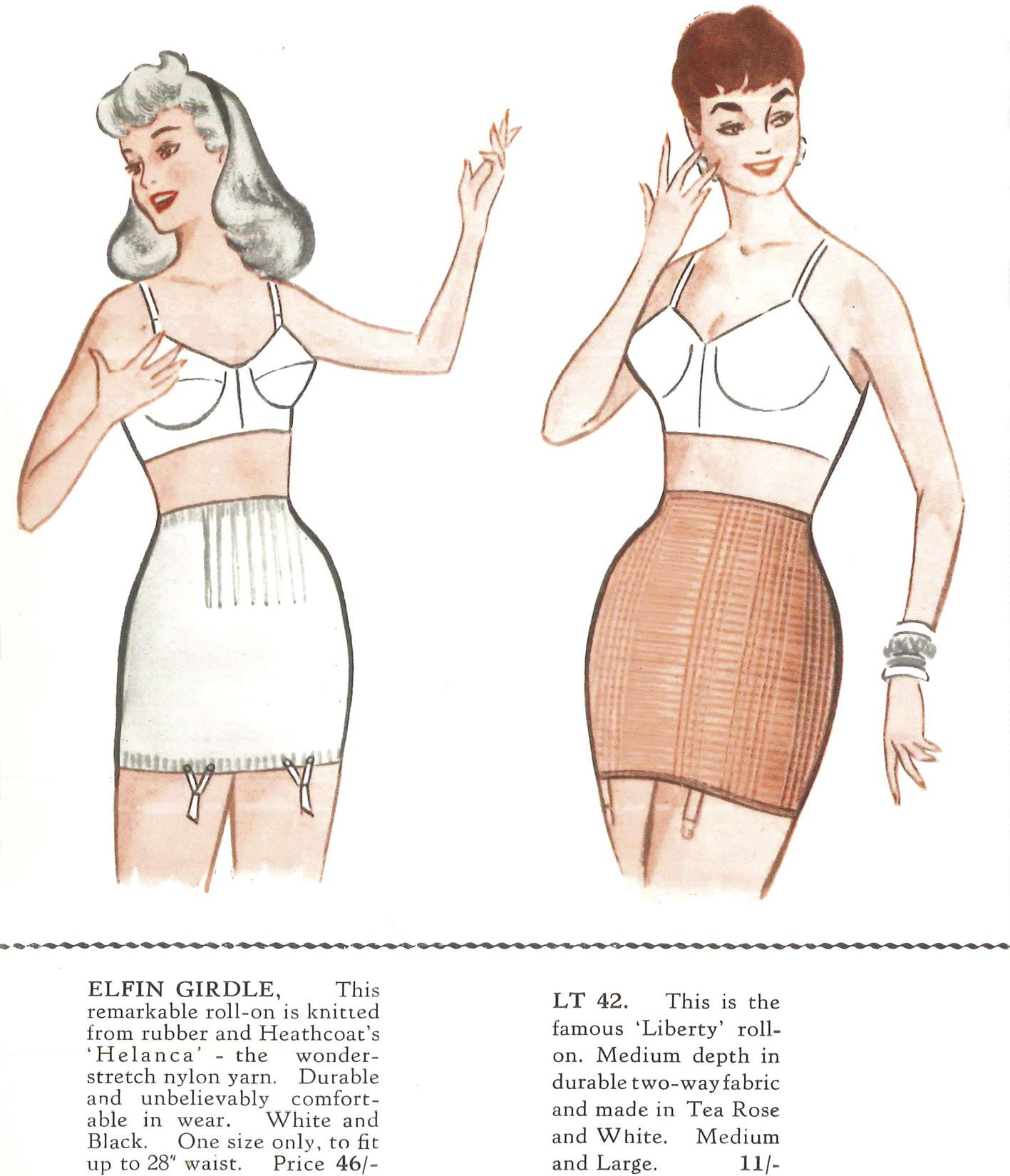

While girdles and corsets were no longer absolutely compulsory, structured underpinnings were essential. In the early 1950s, the ‘waspie’, a tight, abbreviated corset-belt, might be worn to emphasise the New Look’s trim waist. It was most effective on slim figures with little body fat to bulge above and below. For less lissom figures, full body corsets proved more effective. One popular style of sturdy elastic jersey girdle was called the ‘roll on’. There remained a strong market for the traditional ‘ironclad’ corset-girdle in heavily elasticated and boned ‘tea-rose’ coutil, little changed since the late Edwardian era. However, pretty lingerie-styled corselettes, garnished with lace, embroidery, diamanté and ribbon, were widely publicised. One of London’s highest profile corsetières was a Russian émigré, Illa Knina, based in Mayfair from 1939 to 1970, who produced gorgeously coloured and trimmed corsets and bras, often in vibrant prints that camouflaged their essential functionality. In 1953, Charmis even offered a glow-in-the-dark corset appliquéd with tulips, probably more of a publicity stunt than a serious proposal. Knickers could be just as frivolous. The tennis player Gussie Moran’s lace-trimmed panties, glimpsed as she bounded across the Wimbledon court in 1949, caused a media sensation.

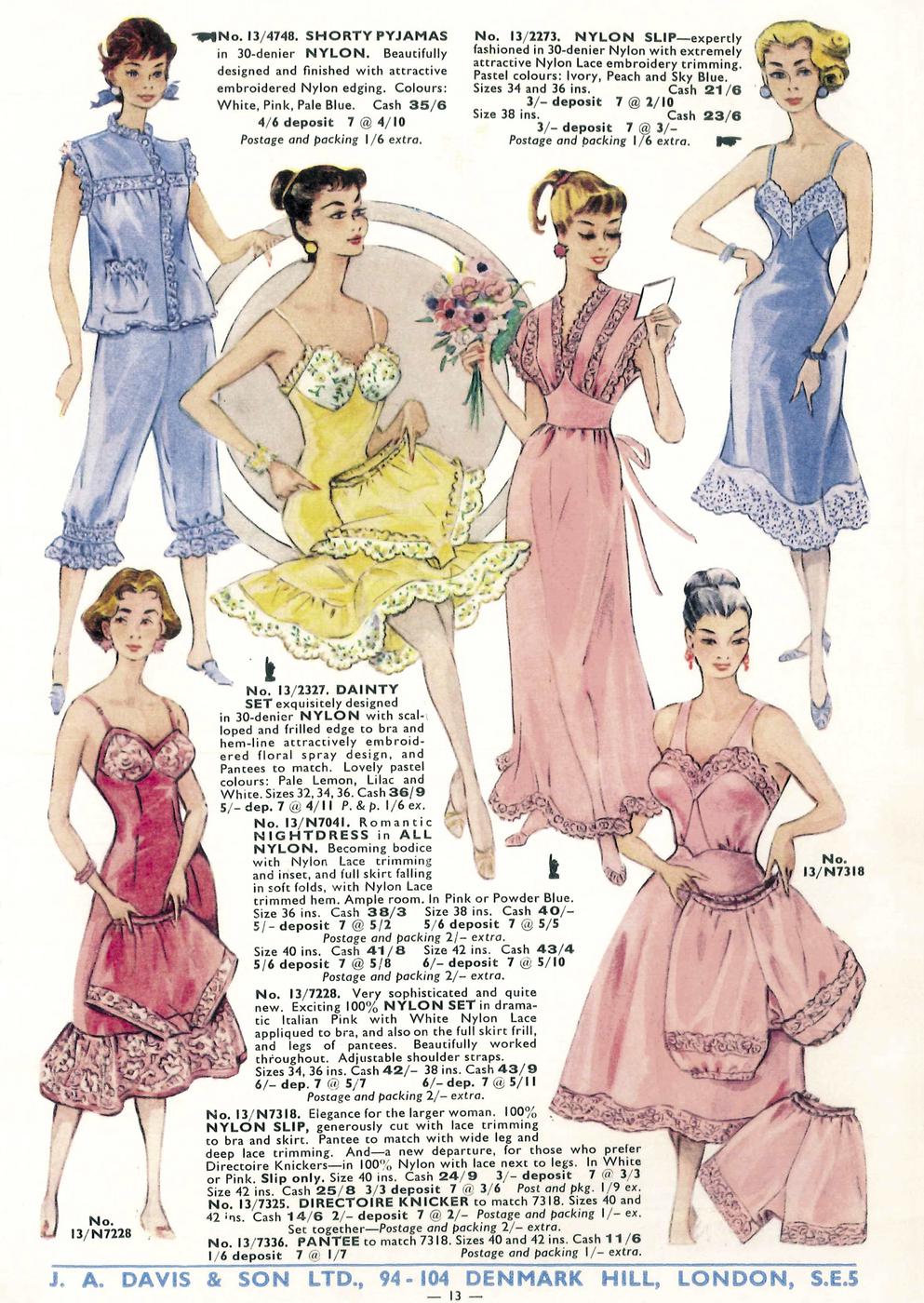

This 1958 catalogue offers a selection of lacy, ruffled nylon petticoats, knickers and sleepwear available in various colours.

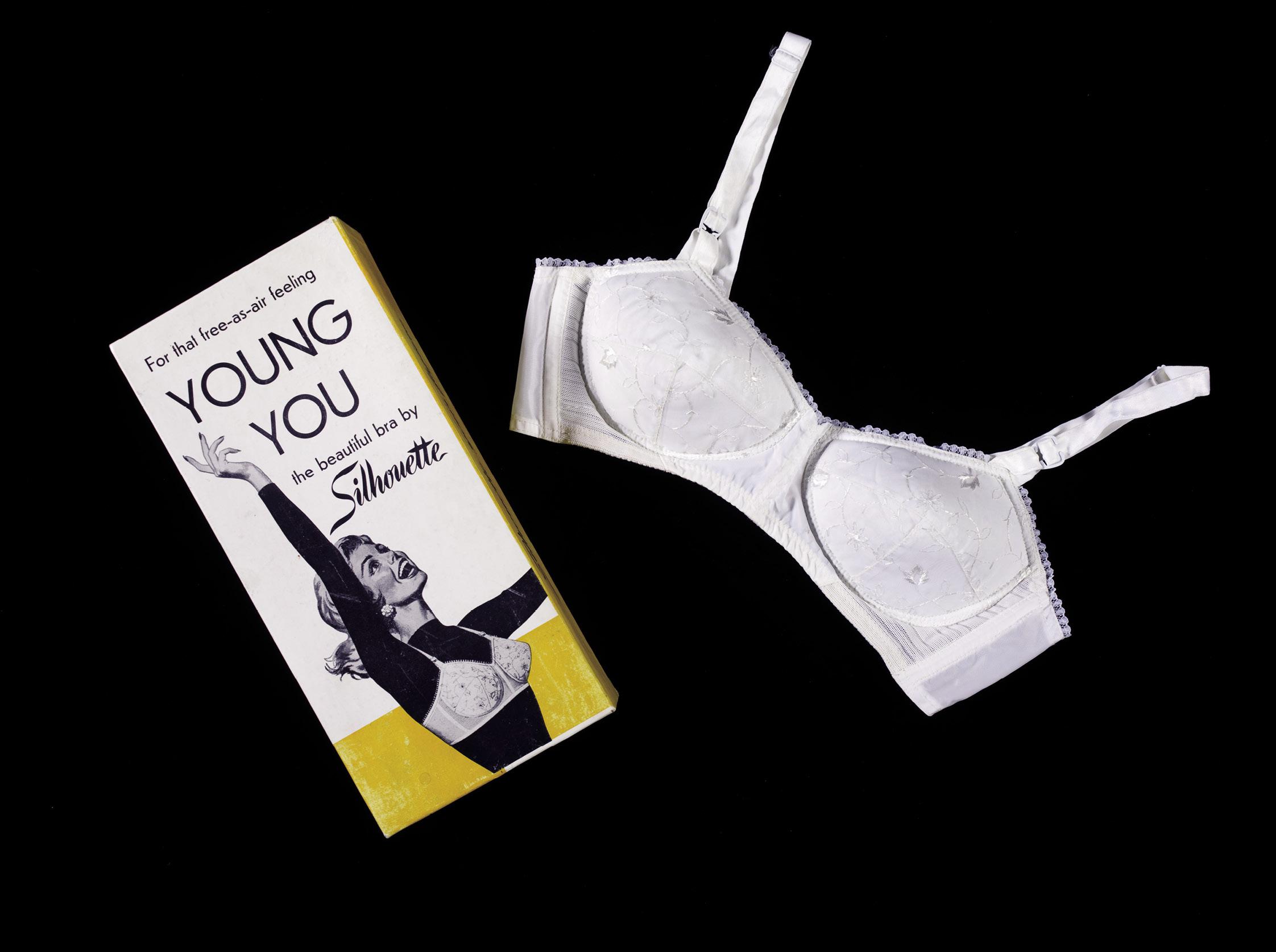

Though technically a functional (and often essential) support garment, the brassiere took on a certain potency among younger and brasher wearers who favoured spiral stitched cups for an exaggeratedly conical profile – particularly under tight sweaters. Padded bras were an option for small-busted women. Bras and girdles were often combined into bustiers suitable for strapless or low-cut dresses. By 1955, the fashionable bustiers and longline bras of the moment were summed up by Alison Adburgham as a ‘caress of nylon, lastex and lace’, some so lightweight that they rolled up as small as the nylon stockings held up by suspenders either attached to the girdle, or to a separate suspender belt.

Roll-on girdles, as shown in this 1956 advertisement, were made from knitted rubber and nylon and were designed particularly for younger women.

Full skirts required the support of layers of starched, stiffened petticoats, made of net, nylon and lightweight canvas. Many women used sugar water to stiffen their crinolines, which could be part of the dress, but were often separate slips. Anne Fogarty, famous for her tiny-waisted ‘paper doll’ silhouette with multi-layered skirts, insisted that bouffant petticoats were valid everyday garments, even for travelling, as they compressed into small spaces and sprang back afterwards. In 1953, in addition to flying out to Ireland wearing four petticoats, she squeezed another eighteen, including three long hooped evening slips, into one suitcase – which unsurprisingly burst open and showered its contents over a hapless customs inspector. Some skirts were made with channels for threading flexible steel, nylon or plastic strips through. While flouncy nylon crinolines, intended to be seen in movement, remained popular for dance dresses and young fashions such as the circle skirt, by 1957, the new slimline fashions required straight-cut, unadorned underskirts. An exception was the ‘Espresso slip’, whose frothy, frilly hem was designed for ‘accidental’ glimpses while its wearer perched on a high bar stool.

Alongside the roll-ons, Symington’s also offered conservative corsets and girdles in ubiquitous pink (‘tea rose’) broché. Some of the sturdier models had interior hip-bands or ‘underbelts’ for extra control.

While this c.1960 brassiere has thickly padded and sculpted cups to emphasise the bust, it was still marketed as being designed to enable freedom of movement and activity.

Pyjamas were increasingly accepted as part of feminine sleepwear. By 1957, the concept of the ‘babydoll set’ with puffy knickers barely covered by a skimpy nightie was well established. Nightgowns could be a variety of lengths, from full length to ‘babydoll’. They came in a variety of fabrics, from sheer nylon to flowered cotton flannel, and often had coordinating dressing gowns – either practical quilted housecoats or extravagantly flowing, diaphanous negligees. Men’s pyjamas followed the traditional form of buttoned jacket and loose trousers, but instead of plain or striped cotton, were increasingly likely to come in livelier prints in ‘easy-care’ nylon and polyester blends.

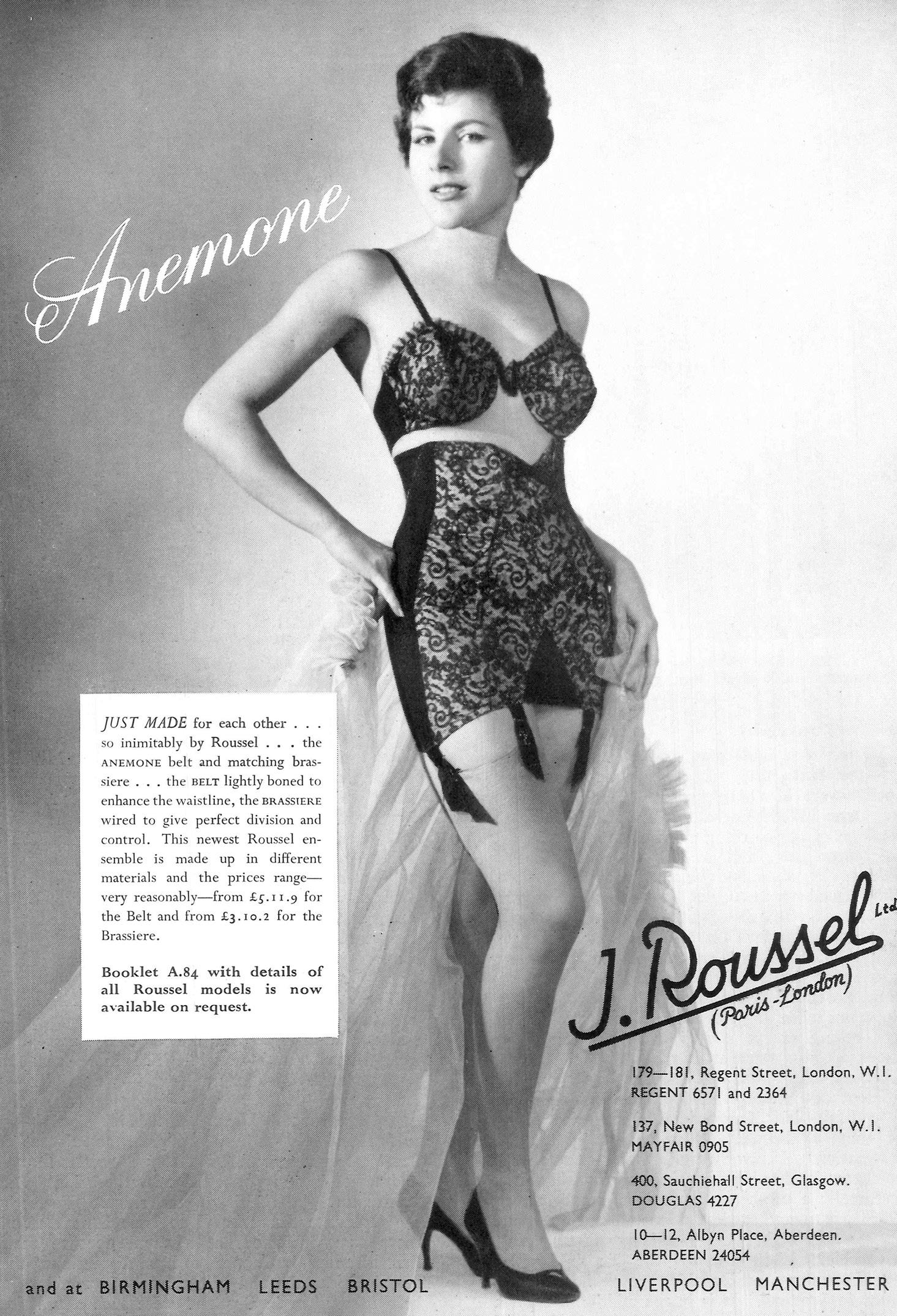

Girdles and bras did not necessarily have to look functional. The corsetière J. Roussel offered their ‘Anemone Belt’ and matching wired uplift bra in seductive black lace.

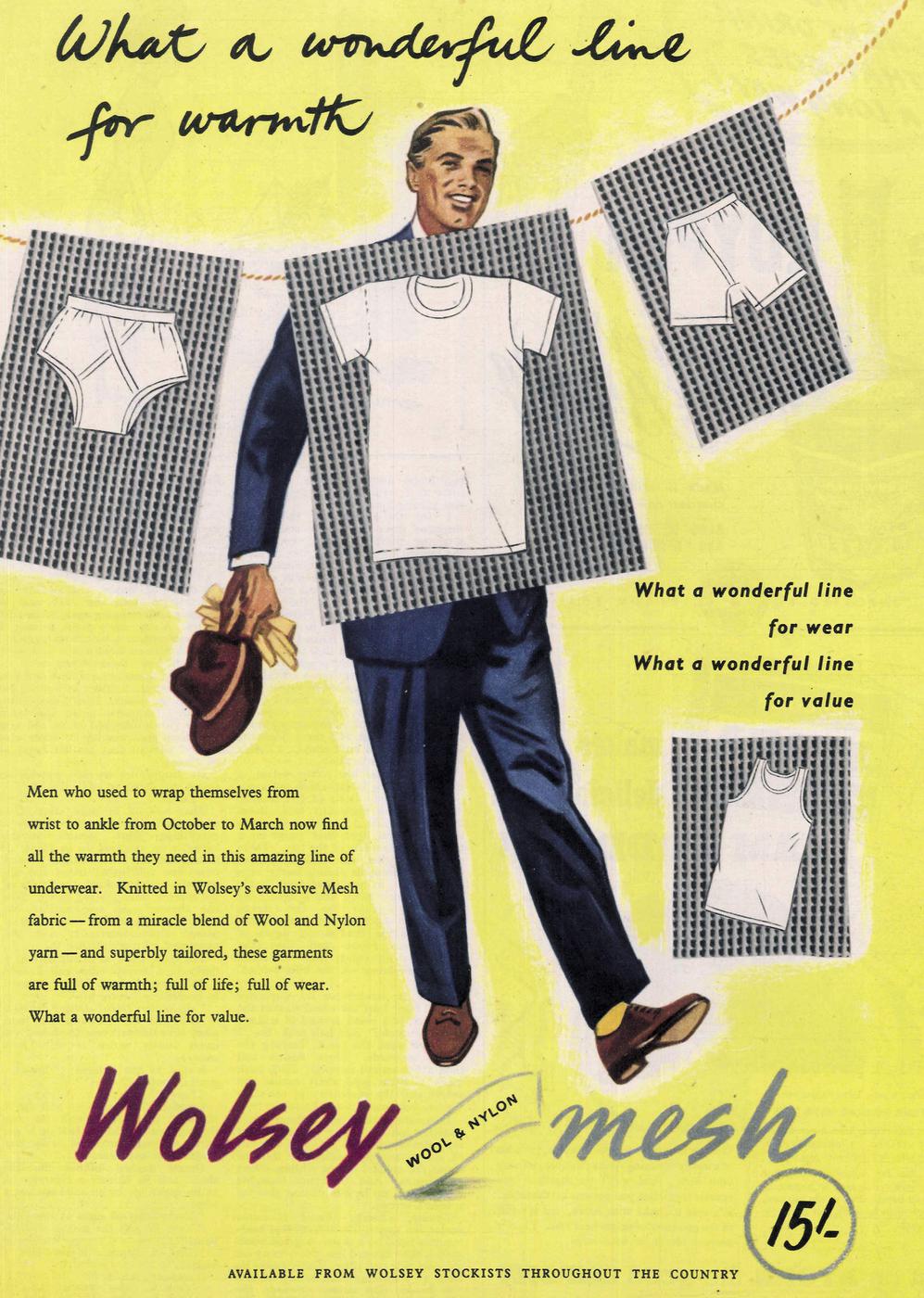

Cotton jersey knit pants and undershirts remained part of masculine underwear, just as they had been for the last fifty years, although boxer shorts (a 1920s introduction) were also worn, despite their lack of support. While underpants were becoming shorter and increasingly brief, the short-sleeved, high-necked cotton jersey undershirt – or T-shirt – was on the verge of a breakthrough. Some twenty years earlier, undershirt sales dropped after the actor Clark Gable revealed a bare chest beneath his shirt in the 1934 film It Happened One Night. While manual workers since the late nineteenth century had frequently stripped to undershirts for convenience, and to keep outer shirts clean, undershirts were firmly considered underwear until the 1950s, when Hollywood once again exerted its influence. Marlon Brando famously wore a T-shirt in his smouldering, anti-heroic role in A Streetcar Named Desire (1951), and again, under his leather jacket in The Wild Ones (1954). By the end of the 1950s, countless publicity shots, both American and European, of youthful singers and brooding muscular actors in T-shirts helped re-establish such garments as a highly visible, essential part of the young man’s everyday informal wardrobe. They were worn for summer wear, with jeans, or for active pursuits.

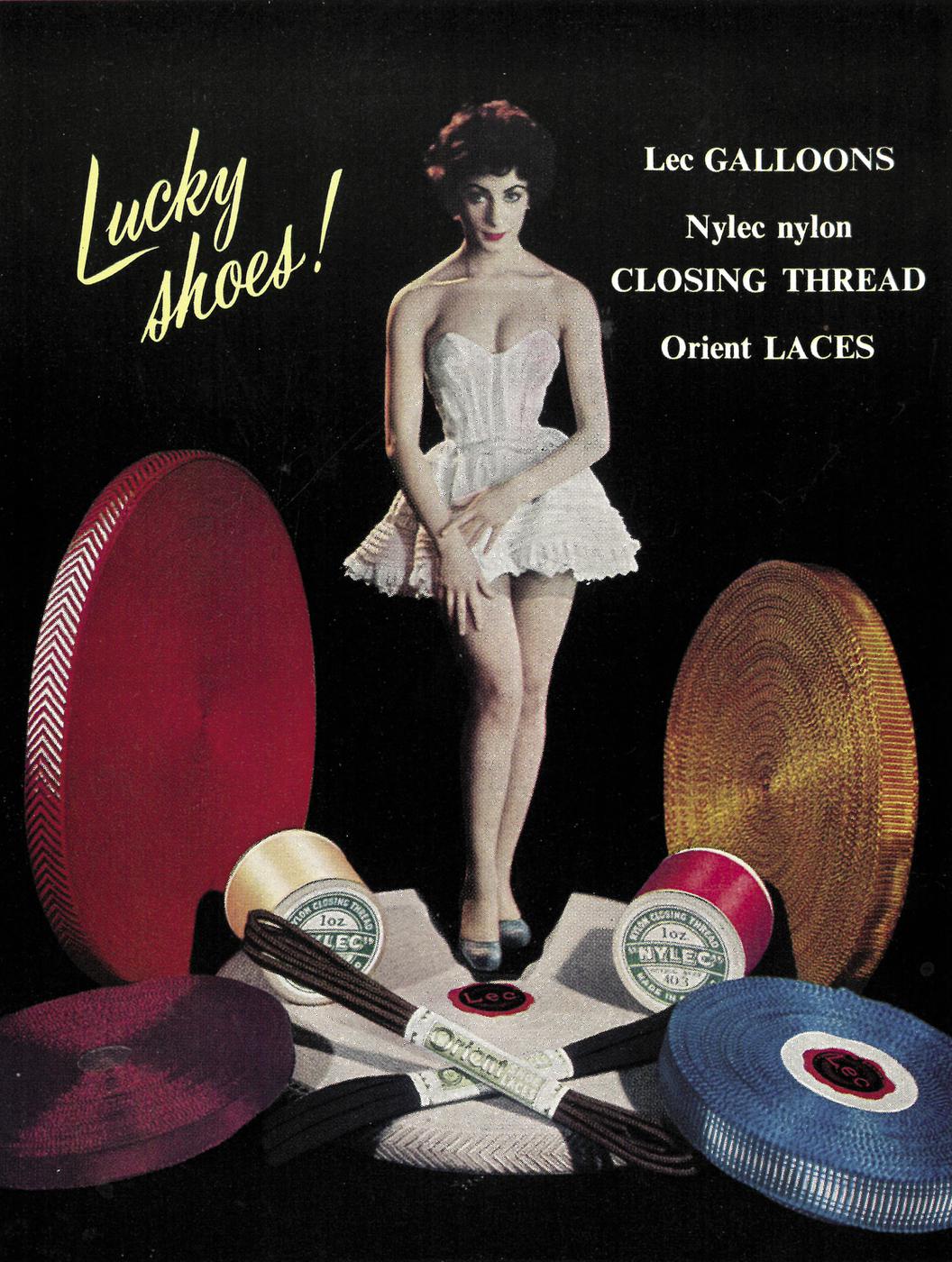

This woman from a 1955 advertising image is modelling a longline bra and short crinoline petticoat. This would have supported the fullness of a longer skirt, enhancing the swish and movement of the fabric as the wearer walked. Crinolines were also available in longer lengths.