CHAPTER IV

The electric washer was a big help. Lula Bell went around to Mama Hattie’s old customers and several of them began to bring their washings in. Mama Hattie was happy because she had work to do and it brought in a little income. She did three, often four washings in a week. She saved the money to make the monthly payments.

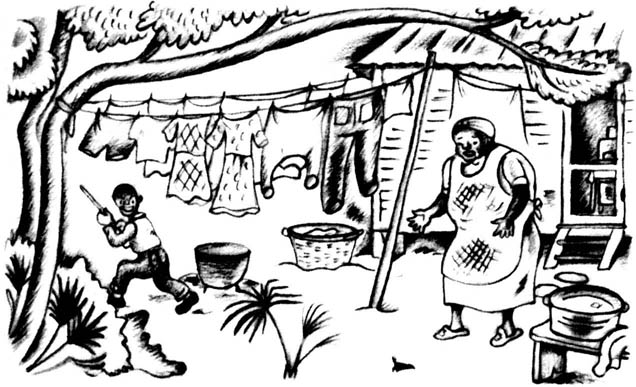

Then one day, she heard a noise back of the house. Out in the yard under the clothes line, she found a dead mocking bird. She saw James Henry Thorpe scooting away with his BB gun. She held the bird in her hand and looked at it. Then she buried it tenderly. It had sung for her in the mulberry tree day after day. She knew that killing a mocking bird meant bad luck and it worried her. She hoped something terrible would not happen, but she had never known the sign to fail. She said nothing to Imogene. Imogene would only laugh at her for believing in signs.

Lula Bell went down to the bayou fishing with the other children that evening and came back late. The fish were not biting, so she had none to bring home. She set the fishing-pole against the house and went in. She felt a little ashamed, for she had hoped to bring a mess for supper and some extra to sell.

“Where you at, Mama Hattie?” she called.

Her grandmother was not sitting on the porch. The radio was quiet and the house seemed empty. In the kitchen, a big washing was half done. Washed clothes lay in the basket, ready to hang out. It was almost supper time. Where had Mama Hattie gone?

Suddenly the girl heard a moaning sound coming from her grandmother’s bedroom. She went in and was surprised to find Mama Hattie in bed.

“You sick?” she asked.

“No, girl—I had a accident,” said the old woman. “The ’lectric wringer … well, my hand went clean through it. Guess I was pushin’ the clothes through too hard—my hand and arm went through too. But I remembered what the man said. I threw up the handle with the other hand, to disconnect it …”

“What then?” asked Lula Bell, open-mouthed.

“Oh Lordy, how it hurt when I got it out—clean up to my shoulder and neck,” Mama Hattie went on. “I thought my whole arm was comin’ off. Nobody was here, so I hobbled over to the preacher’s and Sister Eula rubbed it with alcohol. I stayed there on her bed till the pain eased a little. Then she come home with me and put me to bed here. Oh Lordy, how it hurts!”

Lula Bell stared. “What can I do? Can I rub it?”

“No, honey, I got to grin and bear it,” said Mama Hattie. “The Lord will give me strength. There’s Miz Arnold’s clothes—she depends on me. Can you hang ’em out on the line—them clothes in the basket?”

“Yas’m,” said Lula Bell. “I sure can.”

“But don’t you go near that blessed wringer!”

“I won’t, Mama Hattie.”

Imogene was shocked and grieved when she came home and heard what had happened. Then her grief turned to anger.

“I told you not to buy that washer,” she cried. “‘Good Luck!’—huh! I knew it would bring bad luck on us.”

“It wasn’t the washer,” said Mama Hattie in a low voice. “It was that little dead mockin’ bird.”

Mama Hattie stayed in bed. She had taken cold and it settled in her bronchial tubes. The next day she could not talk above a whisper. She did not want to get up. Imogene had the doctor come for a visit. He said there was danger of pneumonia. Imogene asked her sister Irene to come over and stay awhile.

“I’ll come,” said Irene, “but I got to bring the kids.”

Irene Trimble and her husband, Vernon, lived across town and had four small children. She had to bring them along, as they were too little to stay alone. They were Dora, six, Dean, five, Diane, four, and Debby, three. Vern Trimble picked oranges during the winter and did hauling and trucking in off seasons. He made a comfortable living for his family.

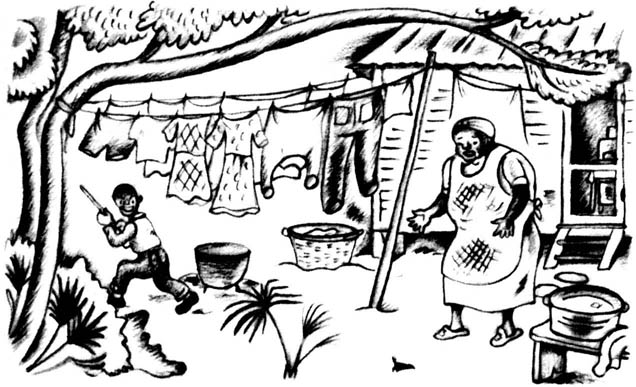

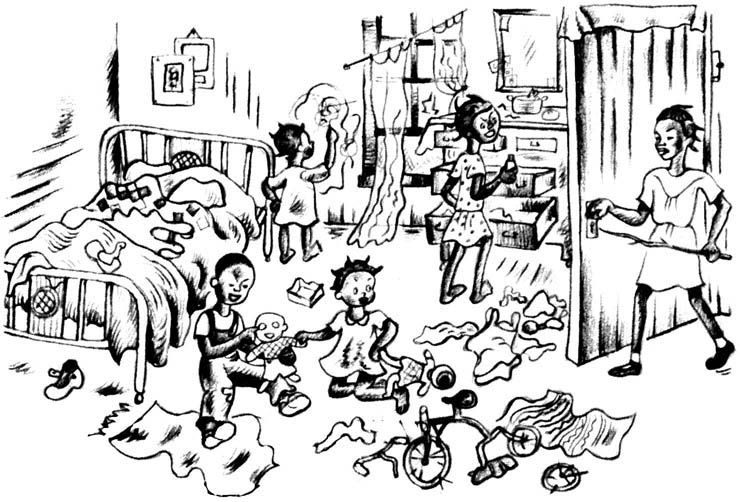

Irene was plump, motherly and good-natured. She looked more like Old Hattie than any other of her daughters. She tried to nurse her sick mother, while her unruly children overran the house. They kept the place in an uproar, and made everything untidy. They were never quiet except when asleep.

“Watch them kids, Lula Bell!” Aunty Irene kept saying.

Lula Bell got tired of watching them. At first she thought they were cute, then they made her life miserable. They tore up her tricycle. It was true she had outgrown it, but it made her cross to see the wheels and handlebars off. The little children punched in the eyes of her dolls. Even though she had left off playing with dolls, it made her mad. They found Imogene’s lipstick and marked red streaks over the walls and furniture. They emptied Imogene’s bureau drawers and scattered the contents over the floor. Lula Bell got blamed for it. She found a switch and used it daily. The children screamed when they saw her coming.

One day Mama Hattie seemed better and asked to get up. She walked slowly into the front room. She wore her dark blue robe and her purple bedroom slippers. She sat down in the platform rocker by the window. Dean had thrown a block of wood through the window pane, so Irene tacked a newspaper over the hole, to prevent a draft. Old Hattie’s face was ashy, and her eyes had a look of sickness in them. Her short uncombed hair stood out stiffly.

“You want I should plat your hair, Mama Hattie?” asked Lula Bell.

“Sure, honey,” said her grandmother. “Aunty Irene, she too busy.”

Irene had brought the ironing board into the front room and had attached the cord of the electric iron to the fixture that hung from the center of the ceiling. On the settee along the wall was a mountain of unironed clothes, some dry, some sprinkled. Irene came in from the kitchen.

“Run over to Miss Lena’s girl, and git a can of chicken soup for your grandma,” she said.

Lula Bell put down her comb and ran out.

“Diane and Debby’s both sick,” Irene went on, starting to iron. “I put ’em both back to bed. They been vomitin’ ever since they got up.”

“That’s too bad,” said Mama Hattie listlessly. She began to cough, and the coughing led to wheezing.

“That cough don’t sound good to me,” said Irene. “Your heart don’t beat strong enough—that’s why you can’t git your breath, Mama.”

“That doctor give me somethin’ to make it beat stronger,” said her mother. “I had to sit up in bed all night. Couldn’t breathe layin’ down. Seems like I’m gittin’ my asthma back again.”

Lula Bell ran in with the can of soup. She started to plat her grandmother’s hair again. Irene turned her iron off and took the can to the kitchen. “You’ll feel better if you eat a little somethin’, Mama.” In a minute she called out: “Lu-Bell, this here’s vegetable-beef. I done tole you to git chicken noodle. Run and take this back.”

“I ain’t hungry,” said Mama Hattie.

“But you got to eat somethin’,” insisted Irene.

When Lula Bell brought the second can, she said to Aunty Irene, “Don’t send me over to Miss Lena’s any more. She’s madder’n an ole settin’ hen.”

Irene opened the can and warmed the contents. She brought in a big dishful, mostly noodles.

“I want crackers,” whined Mama Hattie. “I done tole Imogene to bring me crackers from town, but she didn’t.”

Irene said to Lula Bell: “Go git her a box o’ crackers.”

“Don’t send me over there,” said Lula Bell. “Miss Lena’s mad as hops.”

“Go git a box o’ crackers,” insisted Irene.

Lula Bell flew out the door and across the street. It was ten full minutes before she returned with the crackers. “I got ’em,” she said. “I done made her give ’em to me!”

Mama Hattie tried to eat, but couldn’t. “It needs water,” she said. “It’s too salty. Them crackers got salt on ’em too. If I eat salt, I’ll die—the doctor said so.”

Irene turned on Lula Bell angrily. “Ain’t you got no sense, girl? Why you git Mama Hattie saltines, when you know she can’t eat salt? You can jest go and take this box back.” Irene folded up the torn-open end.

Lula Bell swung her arms angrily. “I jest won’t,” she said, “and I’ll tell you why. Miss Lena don’t take back no boxes that been opened at one end. Besides, Miss Lena has done cut us off!”

“Cut us off!” cried Aunty Irene. “What do she mean—cuttin’ Mama Hattie off?”

“Cut me off?” echoed Mama Hattie, her spoon halfway to her mouth. “Miss Lena can’t do that to me.”

“She didn’t want to give me no can o’ soup,” Lula Bell explained, “’cause Imogene ain’t paid the grocery bill for the last two weeks. She didn’t want to give me no crackers neither, so I snatched ’em off the counter. She said, ‘All right, take ’em, but that’s the last thing you’ll ever git outa my store. Tell Miss Hattie and Miss Imogene I’ve cut ’em off for good!’”

“I never thought Miss Lena would do it,” said Old Hattie, putting her spoon down. “I never thought she was mean enough. I done tole you that dead mockin’ bird meant bad luck. Take this away. I can’t eat a bite.”

Irene took the dish into the bedroom and tried to feed noodles to Diane and Debby. She came out discouraged. “They won’t eat neither. Can’t keep ’em covered up. They’re always sliding off the bed. They got intestinal flu, I think.” She plugged in her iron and began ironing again.

Lula Bell finished platting Mama Hattie’s hair. She crossed the braids over the top of her head and fastened them with hairpins. “Now you look purty, Mama Hattie,” she said. “You look like a queen.”

Mama Hattie did not even smile. “Put me back to bed,” she said.

The next day she did not get up at all, nor the day after that. She slept little at night, her cough grew worse, and she had difficulty getting her breath. The doctor came to see her and wanted to take her to the hospital. Imogene and Irene talked it over.

“Miss Lena cut us off, did she?” snorted Imogene. “Just when I got all these doctor bills to pay. We’ll buy at the Super Market and she can wait for what I owe her. I don’t care if I never pay her now.”

“I think we ought to phone to Ruth,” said Irene.

“It costs too much to telephone all that long distance,” said Imogene. “I can’t pay Miss Lena’s bill and a phone call too. We can’t ask Ruth to pay it. She pays for all the calls she puts through from that end.”

“I’ll pay it,” said Irene, “jest to ease my mind. Vern’s makin’ good money now. I’ll do it for Mama.”

They waited until Irene’s children were in bed and Mama Hattie seemed to be asleep. Then Imogene put the call through. She and Irene and Lula Bell huddled close to the phone, waiting. When the call came, the connection was poor. Irene had to shout to make Ruth hear.

“The doctor said it’s water on the lungs … dropsy … Her heart’s bad and her blood pressure’s too high … What? Yes, two weeks in the hospital. Imogene wants to know how we’ll pay for it … O. K. Next Tuesday … Yes, sure. She wants to talk to you, honey.” Irene turned to Lula Bell.

Lula Bell took the receiver and stood close. “Yes ma’m,” she said. “Jest fine. I helps take care Mama Hattie … Is my daddy up north? You ain’t seen ’im? Yes … oh, goody! You will? Good-by.” She put the receiver back on the hook. “She’s comin’! Aunty Ruth’s comin’ to see us.”

“I bet that call cost you three dollars, Irene,” said Imogene.

“It’s worth it—to git Ruth here,” said Irene. “She’ll tell us what to do. Ruth was always good at bossing us.”

“She’s bringin’ me a present!” cried Lula Bell, dancing on tiptoe and waving her arms. “I wonder what it’ll be.”

In the days that followed, Old Hattie did not improve. A steady stream of visitors kept coming. To each Irene talked patiently.

“She’s jest the same. She can’t eat—we don’t give her salt, so nothin’ tastes good. She drinks a little fruit juice. After midnight last night she got a little sleep …”

Lena Patton came in, with her hair done in two rows of curls around her head and wearing a white figured dress. She stood a while and asked a few questions. But Irene did not offer her a chair or ask her into the bedroom. She did not stay long.

Aunty Velma Henshaw came. “The doctor said she might go at any time.” Aunty Velma looked down at her lifelong friend lying in bed and sobbed.

Miss Eva Burnette, Lula Bell’s godmother, an attractive young woman, came one evening after Imogene got back from work. “You’re givin’ up your job, I suppose,” she said.

“Why no,” replied Imogene. “We never needed money more’n we do right now.”

“I don’t see how you can go to work when your mother is dying,” said Miss Eva.

“Mama’ll get better, the doctor said so,” insisted Imogene.

“You can get a new job,” said Miss Eva solemnly, “but you can’t get a new mother. You can get a new husband or new children, but you can’t never get a new mother. I took care of mine until she passed away and now I have no regrets.”

“A job like mine’s not easy to find,” said Imogene. “My employer has confidence in me, and I’m trying to be worthy of it. I haven’t missed a single half-day since I took this job.”

“When my mother was sick, I missed so many half-days and whole days, I finally stopped going altogether,” said Miss Eva.

“Mrs. Netherton puts her dependence on me,” said Imogene. “I can’t let her down. Too many colored people stay away from their jobs for the slightest excuse. I won’t be like that.”

“Well,” laughed Miss Eva, “if you think more of Mrs. Netherton than you do of your own mother, that’s your affair.” She marched out.

It was an exciting day when Aunty Ruth came. Lula Bell washed and dressed all of Aunty Irene’s children, while Irene cleaned up the house. Lonnie and Eddie tidied up the yard. Brother Williams came in his car and took them all to the station—all but Lula Bell. Mama Hattie was still very sick, but she insisted on getting up and being dressed. She and Lula Bell, both wearing their Sunday best, waited in the front room.

“I wish my daddy would come with Aunty Ruth,” said Lula Bell. “Do you think he will?”

“No, baby, not this time.”

The diesel whistle sounded, then the train rumbled along the tracks two blocks away. It was right on time. Soon the preacher’s car rolled down Hibiscus Street and stopped at the curb. Eddie marched in with two suitcases. Behind him came Aunty Ruth, dressed in pretty clothes, high heels and a tiny hat. She looked like her sisters, but was taller and more aggressive. She ran straight to Mama Hattie and kissed her lightly on the forehead. “You don’t look so good, Mama,” she said.

Then she took Lula Bell in her arms and hugged her tight. She opened her suitcase and handed her a package. Lula Bell tore off the wrappings. It was a red leather pocketbook with a snap and a strap. It had three compartments and a coin purse with a half dollar inside.

Aunty Irene and the children swarmed in, followed by Brother Williams. Imogene came home and they all talked at once.

“I know you are rejoicing to welcome your daughter home, Sister Clarke.” Brother Williams shook his finger at Miss Hattie, “But don’t overdo it. Sister Copeland, we must let you rest after your long trip.”

The next day, the preacher and his wife and Aunty Ruth took Mama Hattie to the hospital. Lula Bell ran up the street to meet Imogene.

“She had a relapse,” said Lula Bell. “She did too much yesterday. The doctor said he couldn’t take care of her with so many people around.”

Irene explained more fully. “The doctor said she ought to be dead by rights, with blood pressure as high as that. He said she might go in one of them coughin’ spells. The hospital’s the only place.”

“What’ll it cost?” asked Imogene.

“Her lodge will pay room and board for two weeks,” said Irene. “The heart specialist will cost fifty dollars.”

“Where’s fifty dollars comin’ from?” cried Imogene in despair.

“We’ll all chip in—you and me and Ruth,” said Irene. “She’s the only Mama we got. Sister Lucy might could help a little too.”

Imogene said nothing. Anxious days followed. The three sisters went often to see their mother. Once Mama Hattie asked to see Lula Bell and Imogene took her. Children were not allowed in the hospital, but they let Lula Bell in. Her grandmother stared at her as if she did not know her. She did not say a word. When they came out, Lula Bell cried and cried.

“Is Mama Hattie fixin’ to die?” she asked.

“She’ll be better soon,” said Aunty Ruth.

Then Irene brought word from the hospital that Mama Hattie had asked all her friends to pray for her. Brother Williams offered a prayer at each service at Rose of Sharon Church on Sunday. The neighbors all said they would pray.

At the end of two weeks, the doctor said they could bring her home.

“He can’t do nothin’ to help her,” said Miss Annie Sue, weeping. “He’s sendin’ her home to die.”

“No ma’m, she’s better,” insisted Imogene. But her voice was low and sorrowful, and she looked utterly sad and spent.

Every one had given her up, but Mama Hattie surprised them all. When she was brought back home, she began to improve. In a week, even the doctor felt hopeful. “If she takes care and leads a quiet life, and if she follows the diet I’ve laid out,” he said, “she will live a year and maybe longer.”

“Only a year?” cried Irene, grief-stricken.

“Maybe she’ll get along all right, but I’m kinda doubtful,” said Imogene. “She’s so hard-headed, she won’t do what we tell her.”

“She’ll mind you now, I think,” said the doctor.

“She’s been near Death’s door,” said Brother Williams.

All the neighbors came to see her, Sister Eula, Miss Annie Sue, Aunty Velma and others.

“I thought the Lord had called me and it was my time to go,” Miss Hattie told them.

“The Lord’s got work for you to do,” said Sister Eula.

“I wish He’d tell me what it is,” said Miss Hattie. “My girls are all lookin’ out for themselves, and my two boys don’t need me any more.”

“How about your granddaughter?” asked Sister Eula. “Seems like she needs you—to help her get growed up.”

“You mean Lula Bell?” asked Miss Hattie. “She’s jest a baby. And she’s got her mama and daddy to look out for her.”

“Have you counted your blessings, Sister Hattie?” asked Miss Annie Sue.

“I got good children,” said Miss Hattie. “I been good to my children. I’ve give ’em the clothes off my back. I’ve let ’em eat while I went hungry. Whatever I had was theirs. I been good to my children.”

“The Lord will bless you for that,” said Aunty Velma.

“If you’re good to your children, they’ll be good to you,” Miss Hattie went on. “Some people’s children don’t care what happens to ’em, but mine do. Ruth put in my telephone and pays the bill each month, so she can talk to me from Jersey. She’s got to go back up north soon, back to her job, so she can make money and pay my doctor bills.”

“Thank the Lord for dutiful children,” said Sister Eula.

“If I could sell this house for $5000, I’d go up north tomorra,” said Miss Hattie, “jest to be with my daughter Ruth.”

“What? Go up north—you, Sister Hattie?” exclaimed Miss Annie Sue.

“Yes, ma’m,” said Miss Hattie. “Ruth put me in the notion we’d be better off up there. I spent the summer with her three years ago. I like it up there. If I could git a flat up there today, I’d move tomorra.”

The women looked at her in astonishment.

“Miss Ruth has sure been workin’ on you hard and fast,” said Sister Eula.

“Ain’t you a-scared of the cold weather?” asked Aunty Velma.

“It was cold in South Carolina where I come from,” said Miss Hattie. “Up north I went out every night with women my age. Here I set on the porch and look. I goes to prayer meetin’ on Tuesday night and to the show on Friday night—if I can git the change. There’s nowheres else to go.”

“But you been sick so much,” said Sister Eula.

“You got good friends here, Sister Hattie,” said Miss Annie Sue. “That’s better’n livin’ among strangers.”

“I got two daughters up there, Ruth and Lucy,” said Miss Hattie. “They got good jobs. They’re doin’ well and makin’ good money. They want me to come.”

The women got up to go.

“You’re not leavin’ soon, be you, Sister Hattie?” asked Aunty Velma.

“Not jest yet,” said Miss Hattie.

On the day that Aunty Ruth left, to go back up north, Lula Bell stayed home with Mama Hattie. They waited a long time for the train whistle, but the train was very late.

“Go fry me a slice o’ white bacon, honey,” said Mama Hattie. “I’m starved for a taste o’ pork.”

“The doctor said no,” replied Lula Bell. “It’ll make you sick.”

“Jest one little slice won’t hurt me,” whined the old woman. “I like bacon and sausage both for my breakfast.”

But Lula Bell was firm and refused. She sat by her grandmother’s bed until she fell fast asleep. Then she ran out into the street to watch for the train to go by. The Hobbs children were playing ball, so Lula Bell took up the bat. Then she heard the long-drawn-out mournful blast of the train. She dropped the bat and waved good-by to Aunty Ruth, as the streamlined coaches passed the end of the street.

“I can’t play no more,” she called to the children, and hurried back into the house. What if Mama Hattie had had a heart attack while she was out? What if she woke up and wanted something?

She rushed in and listened. The radio was still going. She heard a loud thump in the kitchen before she got there. Somebody was walking around. Was Mama Hattie up? She tore into the kitchen like a tornado.

“Why, Mama Hattie!” she cried. “What you doin’ up?”

Mama Hattie jumped—and dropped the frying pan she held in her hand. The piece of white bacon slid off on the floor.

“I’m hungry,” whined Mama Hattie. “They won’t give me nothin’ but orange juice to drink. I’m starvin’.”

“Mama Hattie, you git right back in your bed,” scolded Lula Bell.

Old Hattie opened the icebox door. “I want to see if there’s any steak or hamburger … I gotta eat to git my strength back.”

“You can’t eat red meat,” said Lula Bell. “It’ll send your blood pressure up to the sky. The doctor said so.”

“Fry me an egg then,” begged Mama Hattie. “Two eggs.”

Lula Bell shook her head. “There ain’t any eggs.”

“Yes, there is,” said Mama Hattie, with a sly smile. “My chickens ain’t forgot me.”

“Where your eggs at? You keepin’ ’em hid?” asked Lula Bell.

“In my sewin’ basket,” said the old woman, “there by my bed. I keeps ’em there so I’ll know where they’re at. Eddie brings ’em in to me. Git two. Turn ’em over. I don’t want ’em half done—not with the white a-runnin’. Sprinkle plenty salt on.”

The salt box and a big salt shaker sat on the kitchen table.

“I’ll fix your eggs if you’ll git back in bed,” said Lula Bell. “The train’s done whistled and gone through. Aunty Irene will be back in a minute. If she ketches you outa bed, she’ll take a switch to you.”

Lula Bell helped her grandmother into bed. She leaned back, gratefully, on the pillows, and panted a little. Soon Lula Bell brought in two eggs on a plate.

“This ain’t got a drop o’ salt on it,” said Mama Hattie, taking the first bite. “My tongue feels like it ain’t had a drop o’ salt on it for two years. My mouth’s jest as fresh as a fresh-water lake.”

Lula Bell went to the kitchen. Quickly she emptied the contents of the salt shaker back into the salt box. She came in and pretended to sprinkle salt on the two eggs with the empty salt shaker.

“Oh, this tastes so good!” cried Mama Hattie. “These are the best eggs I ever ate in my life.” She listened, but Irene had not yet come. “Lula Bell, that fryin’ pan out there …”

“I’ll clean it and put it away,” said Lula Bell, smiling.

Out in the kitchen, the girl picked up the salt box and stared at it. Where could she put it where Mama Hattie would never find it? She went in the front room and looked around.

“That’s jest the place!” Lula Bell smiled to herself.

She hid it inside the radio.