CHAPTER VIII

Lula Bell liked it better at Aunt Lucy’s. It was like being at Aunty Irene’s cross-town house because of all the children. Aunt Lucy lived in a real house with a yard around it where the children could play. It was a double house, and she had the upstairs apartment, so there was only one flight of stairs. The downstairs people worked out, so the children ran up and down all day long, unmolested. Lula Bell liked playing with her cousins.

The school on Long Island was better too. To get there, Lula Bell followed a street of houses with yards which reminded her of Hibiscus Street. The houses were set closer together, the yards were smaller, and there were no trees or hedges. But the street was friendly. A flock of children lived there and they all walked to school together. They accepted Lula Bell without question and she felt happy with them.

Cold winter weather set in, which Lula Bell had never experienced before. One day a girl came up and took her by the hand.

“Why, your hands are cold,” she said. “Put my mittens on, won’t you?”

The mittens were bright red and had flowers embroidered on them in bright colors. Lula Bell thought they were beautiful, but she shook her head. “If I take ’em,” she said, “then your hands will git cold.”

“Oh no, I’m warm-blooded,” said the girl. “Your blood’s thin, you’ve always lived in the south.”

The mittens warmed not only Lula Bell’s hands but her heart. From that moment she loved the little girl, whose name was Rose Marie. She decided that Rose Marie was just like her name—as pretty as a rose. On the winter days her cheeks were always a deep pink. Rose Marie asked to have her seat changed to the empty one beside Lula Bell. Rose Marie helped Lula Bell catch up on her work. The northern school was harder than the one down south.

The two girls walked home together arm-in-arm as far as the corner, where Rose Marie turned off. That very first day of their friendship, on their way home, Rose Marie insisted that Lula Bell keep the mittens “for good.”

“I’ve got so many others,” said Rose Marie. “I’ll never even miss them.”

“Won’t your mama care?” asked Lula Bell.

“She’ll never miss them either,” said Rose Marie. “You’re my girl-friend. I want you to have them.”

One day it snowed. A light rain turned into a fluffy snow and covered the ground and yards and roofs.

“Snow!” exclaimed Lula Bell, standing at the school window. “Snow at last. Oh, how pretty it is!”

“You’ve never seen it before?” asked the other children.

“No,” said Lula Bell. “It never snows where I live down south.”

The teacher, Miss Jacobson, heard Lula Bell’s remark, and asked her to tell the children about other things in her home town. Lula Bell’s knees shook as she stood up to talk, and at first she could not remember a thing. Then her courage returned and she told them about all the strange trees and plants she knew so well. She told them about the palm trees and banana trees and pine trees tapped for turpéntine; about hibiscus and gardenia bushes and bougainvillea vines; about the strange fish that swam in the clear blue waters of the bayous, and about the beautiful shells to be gathered on the beaches of the Gulf of Mexico.

Miss Jacobson praised Lula Bell for her talk, and was proud of her. The teacher’s words made the girl happy and inspired her to try harder.

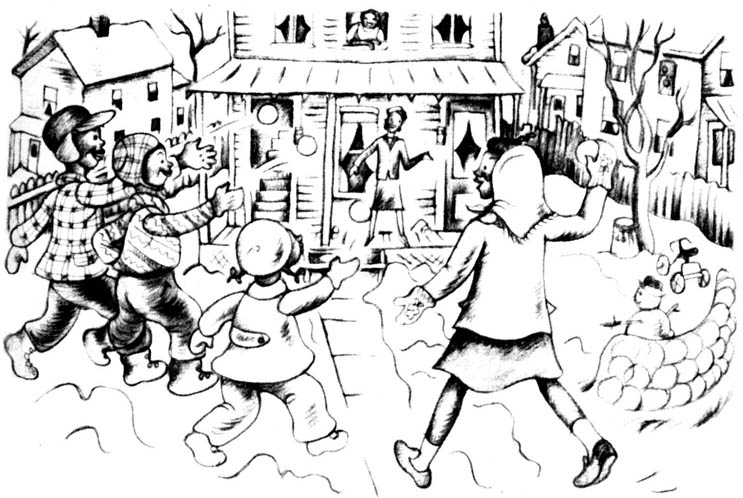

That day she ran all the way home. She did not even wait for Rose Marie. “The snow! Look at the snow!” she cried. Everybody at Aunt Lucy’s was as excited as she was. The children all ran out in the snow. Lula Bell cupped it up in her hands and tasted it. She ate snow and it did not make her sick.

“The snow tastes good!” she cried.

“What do it taste like?” cried little Lenora.

“It taste like snowballs,” said Lula Bell.

The children made snowballs and threw them. Imogene came out on the porch and watched. “Bet you can’t hit me!” she cried. They threw snowballs at her, but she dodged. They missed her every time and she laughed. The snowballs burst open and she laughed. A horse pulling a delivery cart went by. The children threw snowballs to make the horse go fast. They threw snowballs at each other. They did not want to come in for supper.

The snows came and went, and their first glory faded. Lula Bell became accustomed to dirty, black snow, to sleet, slush and ice, to snowballs and icicles. Aunt Lucy’s house was never warm enough, so Lula Bell ran to school each day to keep from getting chilled. Aunt Lucy made over an old wool dress of her own for Lulu Bell to wear in cold weather. She wore the mittens and treasured them carefully. She liked school more and more, because only there was she thoroughly warm.

One period every day had to be spent out on the playground, except when it was raining or snowing, the girls on one side of the building and the boys on the other. Lula Bell hated to go outside on the cold days. The playground teacher, Miss Jarvis, made the girls play baseball and Lula Bell hated that. They were all better players than she was. She was no good at batting and she could never get to the base on time. But Miss Jarvis was patient with her and encouraged her.

Then all at once, Miss Jarvis was no longer just a teacher—she became a friend. Lula Bell and Rose Marie and the other girls admired Miss Jarvis’ clothes and her new car. Whenever they got into fights, Miss Jarvis had an easy way of stopping them and making them feel ashamed of themselves. All the girls wanted to ride in Miss Jarvis’ car and to go home with her for a week-end. They begged and begged, but Miss Jarvis shook her head. “I can’t play favorites,” she said. “If I took one, it would not be fair to all the others.”

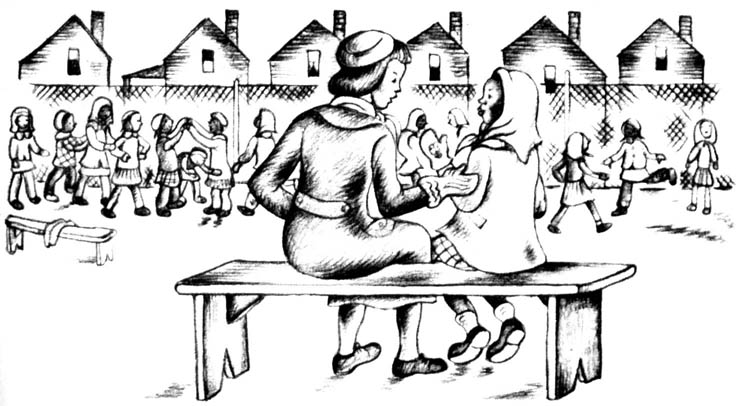

Sometimes Lula Bell sat on the bench beside Miss Jarvis, when she was watching a game. She began to talk to her about the south and she told her how homesick she was. Miss Jarvis sympathized and understood. The other teachers were all so busy in their classrooms there was no chance to visit with them. But on the playground, Miss Jarvis was always ready to listen. Lula Bell was comforted to have someone to talk to.

“You’re my ‘white folks,’ I reckon,” said Lula Bell one day.

Miss Jarvis looked surprised. “What do you mean?”

“Mama Hattie always called Miz Arnold and the ladies she worked for her ‘white folks,’” said Lula Bell. “Even when she couldn’t work for ’em no more, she kept a-sayin’, ‘My white folks’ll take care o’ me. They’ll help me when I needs help.’”

Miss Jarvis smiled. “I do want to help you all I can, Lula Bell.”

“When I first came up north, do you know what I told my mother?”

“No, Lula Bell. What?” asked Miss Jarvis.

“I said: ‘Us ain’t got no white folks that loves us here, have we?’ and my mother say: ‘No.’ She say: ‘We don’t need ’em. We standin’ on our own feet now.’ But I needs ’em!” Lula Bell leaned against Miss Jarvis and put her arms around her.

“Of course you need friends to love you,” said Miss Jarvis, “but you can’t always lean on friends. You must learn to stand on your own feet, too.”

“Yas’m,” said Lula Bell. “Kin I go home with you tonight, Miss Jarvis?”

“No, Lula Bell,” said Miss Jarvis. “It wouldn’t be fair to the others, if I took just one girl.”

“The others don’t love you like I do,” said Lula Bell. “They don’t need you half as much. They been up north a long time. They ain’t homesick no more.”

But Miss Jarvis shook her head, and drove away without any passengers in her car. On their way home from school, Lula Bell and Rose Marie discussed the matter.

“Miss Jarvis took me home with her once,” said Rose Marie. “She’s got a beautiful home, with grass …”

“How much grass?” asked Lula Bell.

“Oh, a big lot of grass, just like a park,” went on Rose Marie, “and a big mansion …”

“What’s that?”

“A big house with a steeple,” said Rose Marie.

“Oh!” cried Lula Bell. “Like in a park?”

“Yes, with trees and flower beds outside,” said Rose Marie. “And two tile bathrooms inside.”

“I sure wish I could go home with Miss Jarvis and see it,” said Lula Bell, “but maybe I’m not good enough.”

“Why, of course you’ve good enough,” said Rose Marie. “You’re just as good as anybody.”

“Then why won’t she take me?” persisted Lula Bell.

“Maybe … maybe …” said Rose Marie, “maybe it’s because you’re colored.”

“Oh!” said Lula Bell, surprised.

“Of course I think you look almost white,” said Rose Marie. “What I mean is—sort of Spanish.”

Lula Bell stopped still and said nothing. Almost white, she thought to herself. That’s why Rose Marie likes me.

“Then if I was awful black, you wouldn’t like me?” she asked.

“Of course I would.” Rose Marie’s affection was real. She put her arm around Lula Bell’s waist. “Maybe it’s not that at all. Maybe Miss Jarvis means just what she says: She can’t play favorites. If she took one girl, it wouldn’t be fair to the others. She treats us all alike. She loves us all the same, no matter what color we are.”

“But you said she took you home with her,” said Lula Bell. “Do she take only white girls with pink cheeks and curly hair?”

Rose Marie laughed. “Oh, did you believe that?” she exclaimed lightly. “I was making all that up. You don’t think Miss Jarvis lives in a big mansion in a park like I said, do you?”

“Why yes, I believed you,” said Lula Bell. “I thought you spoke the truth.”

Rose Marie laughed again, uneasily this time. “My mother says I’ve got too much imagination, and I expect I have. Miss Jarvis lives in an old tumble-down shack …”

“Don’t say that!” Lula Bell began to be angry now. “I know that’s not true. You can just stop tellin’ me lies!”

“Well, to tell you the truth, I don’t really know what kind of a house she lives in.” Rose Marie tossed her curly head. “And what’s more, I don’t care!” She put her arm around Lula Bell’s waist. “Don’t be mad at me, Lula Bell. You’re my girl-friend and I like you.” She began to make up to Lula Bell again.

“I would ask you to came home with me and play in my yard down on Shelburne Street,” she went on, “only my mother wouldn’t let you stay.”

“Why not?” asked Lula Bell.

Rose Marie was too cowardly to give the real reason.

“Oh, because …”

“Then you can come home with me,” said Lula Bell. “I live at my Aunt Lucy’s. I’ve got three cousins—they’re younger than me, but they never play rough. Their names are Roger, Luther and Lenora. Please come.”

They stood at the corner where Rose Marie always turned north to go to Shelburne Street.

“Oh, I couldn’t!” said Rose Marie quickly.

“Why not?” demanded Lula Bell.

“My mother wouldn’t let me go in the colored section where you live,” said Rose Marie frankly. “Colored people are bad and tough and always making trouble. They fight with knives … and my mother says it’s dangerous for little girls.”

“But I go there,” said Lula Bell. “I live there.”

“You’re not a little white girl,” said Rose Marie.

Lula Bell looked at her hard. “At least,” she said, “for once you’re tellin’ the truth.”

The truth rankled even though Lula Bell tried to forget it. She made up her mind not to tell Miss Jarvis. But one day, after Miss Jarvis had started a game at one side of the playground, she came back and sat down on the bench beside Lula Bell.

“Don’t you want to play in the next game?” she asked.

“No ma’m,” said Lula Bell. Then all at once she blurted out the things that had been troubling her.

“Miss Jarvis,” she said, “Now I know why you wouldn’t take me home with you to spend the night. Rose Marie told me. It’s because I’m colored.”

Shocked, Miss Jarvis looked down at the girl.

“Oh, Lula Bell, that’s not true!” she cried. “Rose Marie is wrong. If I took any child, I’d take the colored ones too. I want you to believe me when I say that I am equally fond of every girl on this playground, no matter what color they are.” She smiled. “I’m even fond of the bad ones, who make trouble, because I hope to help them. We have children of many races and from many countries here—Japanese, Chinese, Mexican, European, Hawaiian and a great many Negro. You are not the only one.”

“Down south,” said Lula Bell, “we don’t have white children in the colored schools.”

“I know that,” said Miss Jarvis. “That makes it easier for you in school, perhaps. But does it help you to learn to live out in the world with all kinds of people? Aren’t you glad to get to know Rose Marie and the other white children?”

Lula Bell nodded. “Rose Marie’s nice, but she’s got too much imagination. She makes up things that are not true.”

“You see, Lula Bell, we are all trying to be friends,” said Miss Jarvis, “even though we come from different races and backgrounds. We don’t always succeed, but we are trying. That’s a democracy. You’ll help by being kind and friendly to the other children, won’t you?”

“Yas’m,” said Lula Bell.

After that, things were easier. Lula Bell worked hard and took her books home to study. Miss Jacobson had the Fourth Grade write stories and essays every week. That week she asked them to write on: Why I Like This School. Lula Bell had not had much experience in writing, but she remember some of the things Miss Jarvis had said. She put them down in her own words, and said that her school was a little democracy and the United States a big one. She copied her essay twice, because of all the mistakes. The second time it looked better, and she handed it in.

The next day Miss Jacobson told the class that Lula Bell had won First Prize. She pinned a blue ribbon on her essay, and Lula Bell had to read it aloud to the class. All the children clapped, then they sang “America” and Lula Bell realized for the first time what the song meant.

It was easier to be friendly with Rose Marie now that she understood her better. The two girls walked home arm-in-arm again. Rose Marie was proud that her girl-friend had won First Prize. When Lula Bell got back to Aunt Lucy’s house, she showed her blue ribbon and read her essay aloud.

“Gosh! This young lady’s gittin’ educated!” cried Uncle Nat.

“Mama Hattie always wanted us to get some education, but not too much,” laughed Aunt Lucy. “She used to say: ‘I ain’t got no education, but I got mother-wit to bring up my children.’”

“Times have changed since Mama’s day,” said Imogene. “I could use a little more education than I got in High School.”

“Education for Negroes is O. K.,” said Daddy Joe, “but where does it git you? Does it give you a good job?”

“Some get the swelled head,” said Uncle Nat, “and think they’re big shots. Some educated whites get that way too.”

Lula Bell looked from one face to the other, uncertainly.

“Don’t you like my essay?” she cried out. “What’s the matter? Why you-all makin’ fun of it? Why don’t you say it’s nice?”

“Why, honey, we’re plumb proud of you.” Imogene put her arm around her daughter. “To think you got First Prize in a class with white children! You can write down your thoughts better than your mother can. I got to write a letter to Mama Hattie, I’ll tell her you got First Prize.”

Things continued to go well at school and Lula Bell kept on improving. It was a great shock to her, therefore, when she learned that she could not stay to finish the Fourth Grade.

“We’re moving back to Jersey,” said Imogene one evening. “Daddy Joe and I have talked it over and we think we can do better there. I don’t like this job I’ve had at the laundry here—checking in dry cleaning, and getting paid for the pieces I check in. It keeps me in a rush all day long and makes me so tired I can’t sleep at night. Your daddy says the foundry work’s too heavy for him. So we’re going back to Jersey.”

“Don’t Aunt Lucy want us any more?” asked Lula Bell.

“Sure she does,” said Imogene, “but it spoils her home life to have another family on top of her like this. She can’t do right by her own husband and children. She begs us to stay, but I know we can’t go on like this. So we’re going back to Jersey.”

“Back to Aunty Ruth’s where the landlord put us out?” asked Lula Bell.

“Well, no … we can’t go there,” said Imogene.

“Back to that terrible school and those terrible kids on Mechanic Street?” demanded Lula Bell.

“Well, no … you wouldn’t like that, I guess,” said Imogene. She paused. “But you can’t always be thinking only of yourself. There are other things more important than you.”

“There are? What?” asked Lula Bell.

“All kinds of things,” said Imogene. “A place to live in at a price we can afford, a job for Daddy Joe—work he can do without killing himself and get good pay; a job for me—work I can do without killing myself and get good pay. Then we’d like to be somewhere near Aunty Ruth and Uncle Theodore. We’ve got to have some friends, a little social life …”

“I won’t go back to Mechanic Street,” said Lula Bell stormily, “and you can’t make me.”

Imogene did not press the matter. She was too unsure of everything in her own mind. Sometimes she saw clearly the advantages of living down south and was ready to take the next bus and leave the north behind. At other times she remembered the south’s disadvantages and lack of opportunity, and was determined to win out up north. The south was in her blood, and through every meager letter written by her sister Irene, it was calling her back insistently. But the north filled her mind and strengthened her determination. The south was a lazy dream. The north was a challenge. She must stay. She must work until she got ahead and saved some money. At least she would postpone going until then.

But what to do with Lula Bell?

She knew that Mechanic Street and the overcrowded city school were not right for the girl. She had watched Lula Bell change rapidly for the worse under their short period of influence. She felt a genuine responsibility for her daughter for the first time, because the girl was now removed from her grandmother, who had previously and so capably assumed it.

“I used to say it down south: ‘What’s the use of trying to bring up your child to be good, when all the other kinds are bad?’ But now I say it up north. I used to think there were enough bad kids on Hibiscus Street, but when I think what those Mechanic Street kids done to poor Lula Bell …”

“We can’t take her back to that,” said Daddy Joe.

“Where’ll I go then?” cried Lula Bell, bewildered.

The uncertainty began to tell on her. Her school work grew worse and worse. She could not write, she could not think. She could not even read—the words swam before her eyes. She stayed out of school now and then. Finally she stayed out altogether.