CHAPTER X

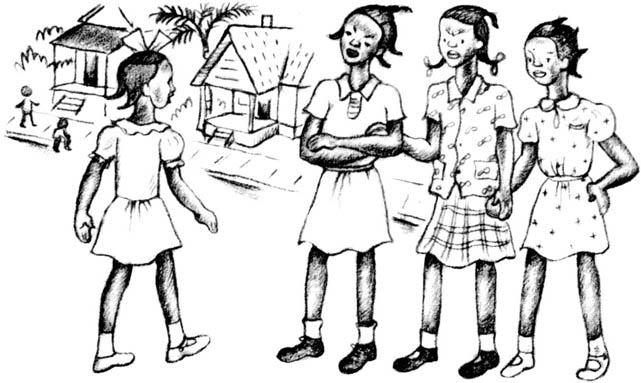

Josephine, Geneva and Lula Bell stopped on the corner by the Chicken Shack on their way home from school.

“Lula Bell!” called Mama Hattie from her porch. “Come here and git Myrtle. She wants to play with you-all.”

Lula Bell turned to the girls and said, “It’s that kid from Chicago. We don’t want her, do we? She plays with dolls all the time. What’s more, she’s sleepin’ in my bed and her mother’s driving us out of our own home. They’re boarders—but they act like they own it.”

“We don’t even know her,” said Josephine. “She ain’t ever come to school.”

“I’ll send her right over,” called Mama Hattie.

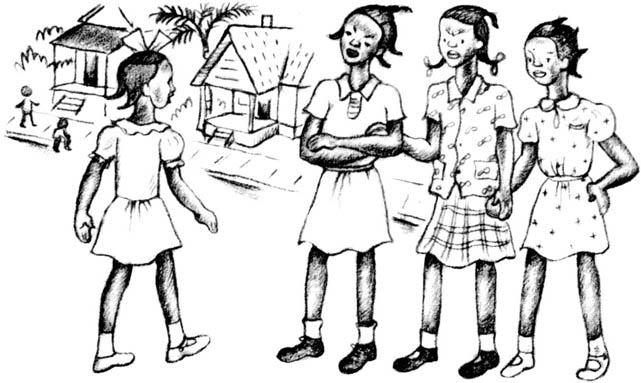

As Myrtle came slowly across the street, the three girls looked her up and down. Their unfriendly glances made Myrtle stop halfway.

“We don’t want you!” said Lula Bell coldly.

As she said the words, she saw a shadow of worry pass over Myrtle’s face. Her own words had a familiar ring to Lula Bell. They took her back to a crowded street in a northern city. A group of children there had said: We don’t want you. Lula Bell’s heart began to pound, and she felt very guilty. Why, Myrtle must feel the same way right now to hear that she was not wanted. Lula Bell felt ashamed of herself inside, but decided not to show it.

After all, why should she care how Myrtle felt? Myrtle could find her own friends. The three girls watched Myrtle turn around, go back home and sit on the porch again. She picked up her baby-doll and hugged it tight. Mama Hattie was indoors now.

“Maybe Myrtle’s O. K.,” said Geneva. “That’s a nice doll she’s got. It cost a lot o’ money.”

“I tell you she stoled my own bed that I slep’ in all my life,” repeated Lula Bell, “and her mother’s cranky and mean. She won’t feed that old man. She’s lettin’ him starve, while she and Myrtle eat all they want.”

Josephine looked at Lula Bell. “You don’t sound like Lula Bell at all,” she said. “I thought you hadn’t changed, but now I see …”

“How have I changed?” demanded Lula Bell, frowning.

“Oh, in little things … jest in little things,” said Josephine. “For instance, you won’t climb up in the old chineyberry tree any more.”

“It’s blown down,” said Lula Bell. “It’s no fun to climb up in a broke-down old tree. And besides, I got my school dress on.”

“Go put on your jeans,” said Geneva Jackson. “Then you won’t have to be careful.”

“Aw, come on,” called Josephine. “Let’s see how high up in it we can go. That cross limb would make a good seat to sit on. Floradell will be here in a minute.”

Lula Bell was bored, but she followed the others, stepping from one limb to another. Near the top of the fallen tree, the three girls sat down on a cross limb. Geneva began to shake it.

“What’s fun about this?” grumbled Lula Bell.

“We’re on top o’ the world!” cried Josephine. “If we had wings like angels, we could fly up in the clouds!”

“If we had wings like seagulls,” said Geneva, “we could fly out over the sea.”

“Oh phooey!” cried Lula Bell. “Don’t be silly.”

Suddenly a loud commotion was heard inside the Chicken Shack. Men’s angry voices rang out, dishes clattered, and heavy thumps were heard. The door flew open with a jerk and a man was kicked out bodily onto the sidewalk.

“You git outa here and don’t you never come back!” shouted Andy Jenkins. The door closed with a loud bang, and a key turned in the lock.

“Yes ma’m, we can see everything!” cried Lula Bell. “Too much, I say. Let’s get down outa here.”

The girls slipped hurriedly down from the tree. Lula Bell looked with the others at the man lying on the sidewalk. A crowd of younger children gathered. Lula Bell recognized the Pearson boys. Suddenly little Popsicle began to cry out. His cry turned into an open-mouthed bawling.

“It’s my daddy!” he wailed. Little Shadow cried too.

“Let’s go away from here,” said Lula Bell. “I can’t stand this awful Hibiscus Street. Why they got to have taverns right on our corner, I can’t see! That awful Mr. Andy and his Chicken restaurant …” She took Geneva by the arm and pulled her along. Josephine followed. “Oh, those terrible people!” cried Lula Bell.

“What terrible people?” asked Geneva.

“Who you talkin’ about, anyhow?” asked Josephine.

“That Pearson family,” said Lula Bell. “Luke Pearson lying there dead drunk. And Big Ethel his wife—so loud-voiced you can hear her a mile off. Those little brats, Popsicle and Shadow, always in the way … taggin’ after us. They never stay at home where they belong.”

“It’s not very pleasant at their home,” said Josephine slowly. “They like to come out on the street just to have a little fun.”

“Poor little kids!” said Geneva. “I’m gonna buy them some popsicles.” She darted into Miss Lena’s store.

“I wouldn’t spend a penny on kids like that,” Lula Bell called out. “I wouldn’t associate with people like that. My mother wouldn’t let me.”

Josephine looked at her in astonishment.

“Is Miss Imogene gittin’ snooty now that she’s livin’ up north?” she asked. “It’s only Popsicle and Shadow …” but somehow she knew Lula Bell would not understand. “Popsicle jest loves popsicles …”

Geneva came out with two big double sticks of bright green frozen flavored ice. She ran over and gave one each to the Pearson boys. Other children had broken limbs off the big tree and were poking at the drunkard. The man raised himself and leaned against the shoe-black stand. He opened his eyes and tried to snatch at the sticks. Lula Bell watched with disgust.

Down the street came a young girl of about fourteen, wearing a red hibiscus in her hair, and a red sweater over a purple dress. Her long thin brown legs came dancing down the street, as she sang lustily:

“‘If I’d a knowed you was a-comin’

I’d a baked a cake …’”*

Now and then she stopped and struck a posture, as if pleased with herself. At first, Lula Bell wondered who it was. Then she saw that it was Floradell. She looked different, she had grown so tall in the last six months. Then she remembered that Floradell was the older sister of Popsicle and Shadow.

After Floradell called “Hello!” she looked over and saw the man. At once all her spirits faded. Her whole figure seemed to droop. She walked over and helped the man to his feet.

“Come on home, Pop,” she said in a matter-of-fact voice. “See you later, girls.”

A duty had to be done, and Floradell did it. She guided her father down the street to the two-story house, half-hidden behind the trees. Popsicle and Shadow followed, sucking on their ices. It was a sad little procession. When they turned in at the gate, the loud voice of Big Ethel could be heard.

Suddenly Geneva and Josephine said, “We got to be goin’ home.”

“If you-all go, I ain’t got anybody to play with,” said Lula Bell.

“There’s always little Myrtle!” the girls answered, laughing. “Little Myrtle and her doll-baby!”

They ran off up the street and Lula Bell came slowly over to Mama Hattie’s house. Here, the smaller children were making sand-pies on the sidewalk. They had collected jar-lids and filled them with dampened sand. Dozens of pies were spread out over the walk. Lula Bell jumped in the middle and kicked them in all directions.

“You spoiled our pies! You spoiled our pies!” cried Clarence Hobbs and the others. “You’re mean—we don’t like you.”

The little girls began to cry. Lula Bell chased them around to the back of the house and told them to stay there and keep quiet.

Mama Hattie and Myrtle were sitting in two chairs side by, side on the porch. As Lula Bell came up, Myrtle quickly put her baby-doll down on the floor back of her chair.

“Set down, Lu-Bell,” said her grandmother. Lula Bell started to open the screen door to go in. “Come back here and set down, I said!” repeated Mama Hattie sharply. Lula Bell sat down.

All of a sudden she heard the little children crawling under the house, making loud noises. “I tole those crazy kids to be quiet,” she said. “What they doin’ now?”

“They’re playin’ hogses,” said Mama Hattie, smiling. “They can root jest like big ole razorback hogses. You used to do that when you was little, you and Floradell and Josephine.”

Lula Bell turned up her nose. “We don’t play hog-games up north,” she said.

“What do you play?”

The question came from little Myrtle, who seldom said a word. As Lula Bell remembered the Trick Shop tricks, pain hit her in a flash. That was one thing she would never tell anybody. She stared coldly at Myrtle and said, “None of your business.”

“Lula Bell!” scolded Mama Hattie. “Myrtle asked you a civil question. Give her a civil answer.”

“Oh, we have lots of games of our own up north,” she said. “Quite different from here. They never heard of the backwoodsy games the kids play down south.”

She had forgotten that Myrtle was not a southern child. It surprised her when Myrtle said: “In Chicago we played Miss Sally Walker and My Bread Is Burning. Do you play those?”

Mama Hattie went indoors, hoping the two girls might become friends more quickly alone.

“No, girl,” said Lula Bell, “they’re too babyish.” Deciding to put on a few airs before Myrtle, she began to brag: “I’m gonna git a two-wheeler bicycle for my birthday. My father and mother are rich. They live up north. Not in Chicago, but near New York. They sent me down here for a short vacation. My mother told me she’d git me anything I want, and I chose a two-wheeler bike. I bet your mother ain’t got money enough to buy you one …”

Myrtle said nothing.

“That’s a fine story,” said Mama Hattie coming out. “I hope Myrtle’s got sense enough not to believe you.”

Myrtle’s mother called and the little girl went in. Their bedroom faced on the porch and the window was open. Lula Bell knew they were sitting in there listening. She and Mama Hattie did not say anything. They sat glumly side by side.

One day Lula Bell came home with a store package under her arm. She opened it up and showed a pretty wall looking glass. “I bought it at the Variety Store,” she said. “It cost $1.98.”

“A lookin’ glass!” Lonnie and Eddie laughed.

“Wants to look at herself,” said Lonnie.

“She’ll be puttin’ on lipstick next,” said Eddie.

“Where’d you git the money?” asked Mama Hattie quickly.

“I … er … well …” Lula Bell began to stammer.

“I missed some money from my pocketbook,” said Mama Hattie. “I been keepin’ it under my pillow. But I found it layin’ out on my dresser and some of my change was gone. If you want money, why don’t you ask for it?”

“Cause you never got none to give me,” snapped Lula Bell, “I know that before I ask you.”

“There ain’t one of my six children I can’t trust,” said Mama Hattie. “They know I only got a little and got too many places for it. Sometimes if there’s some left over after I pays for the groceries, Lonnie or Eddie goes and takes a quarter. They says: ‘I taken a quarter, Mama,’ and that’s O. K. They never been sneaky.”

“So you think I been sneaky!” Lula Bell flared up. “If you’d give me 50¢ a week for spending money, like Daddy Joe did up north, I wouldn’t have to help myself.”

“I can’t, honey, I ain’t got it to give,” said Mama Hattie. “Joe can throw his money away if he wants to. I got to hang onto mine.”

“I need a two-wheeler,” said Lula Bell, “so I can ride to school. You gonna buy me one?”

“No, girl,” said Mama Hattie. “Your legs gittin’ weak?”

“You bought bikes for both the boys,” said Lula Bell.

“They had to have ’em to git out to the Golf Links to git their Saturday change,” said Mama Hattie. “They earned the money and bought ’em second-hand. You don’t need a bike.”

“I got to have some spendin’ money,” insisted Lula Bell. “If you won’t give me none, I purely got to help myself. You know what you’re doin? You’re makin’ a thief outa me, that’s what you are.”

Swiftly Mama Hattie’s hand flew out. It gave the girl a resounding slap on the side of her face. “Don’t you git fresh with me, girl!” she said.

Lula Bell was too astonished to cry. Her grandmother had never slapped or whipped her when she was little. She had left all that to Imogene. Now, the blow left a sharp sting, a sting of pain and of injustice.

“I’m gonna git me a job and have my own money!” she threatened.

“I hopes you will, in a few years from now,” said Mama Hattie. “Ten’s a little young.”

“Right now, I mean!” cried Lula Bell. “I’m gonna run away from here and git me a job … I’ll go back up north and live with my mother and Daddy Joe. The Greyhound bus will take me six blocks from Aunty Ruth’s apartment house. I know the way and I’m goin’.”

“All right, Lula Bell. Good-by.” Mama Hattie offered her hand.

At first it was only bragging. Then Lula Bell was surprised to find she was putting her words into action. She dashed into her grandmother’s room and began to pack her clothes. She soon had her suitcase filled. On top of her clothes she put the new looking glass. She had bought it with Daddy Joe’s money she had saved up. She had not taken a penny from Mama Hattie and she never would. She’d starve first. It just showed how little Mama Hattie understood her.

She put on her hat and coat, the ones she wore on the bus coming down south. She picked up the pocketbook Aunty Ruth had given her. Suitcase and pocketbook in hand, she marched out of the bedroom, through the front room and out on the porch. Mama Hattie and Uncle Jim and Miss Vennie and little Myrtle were all sitting out there now. They did not say a word. They just watched her go. All the way up Hibiscus Street they watched. Then she turned a corner and was hidden from their view.

Nobody called her back. Nobody said, “We want you to stay here,” or “We’ll miss you if you go.” If Lonnie and Eddie had been at home, they’d have said something. They’d have laughed and joked to make her stay home. But not Mama Hattie or the Bradleys and not even old Uncle Jim who’d eaten that good dinner of hers and let her go hungry. They didn’t care. They just wanted to get rid of her. They preferred that miserable little Myrtle. Well, she’d get out of their way, and let them have Myrtle. This knowledge added to her bitterness.

Lula Bell headed for the Greyhound Bus Station and went in and sat down. She rested until her anger subsided a little. The man at the ticket window called out: “You takin’ this next bus? Hurry up if you want a ticket. Bus’s goin’ out in a minute.”

Lula Bell did not answer.

She opened her pocketbook, but she knew it was empty. She had spent $1.98 for the looking glass, and 11¢ for the show the Saturday before. There was only 3¢ left. She could not travel very far on 3¢.

“Did you come to meet somebody?” called the ticket man. “That bus went out—it’s goin’ up north. There’s no more buses either way today. Were you trying to meet them people who come from Miami?”

Still Lula Bell did not answer. She was faced with a problem. She had run away from home, but she knew she had to go back. How could she do it? The man wanted her to leave, so he could lock up. She picked up her suitcase and hurried out.

Where now? She started off in the direction of Aunty Irene’s house cross-town. But she would meet people she knew over there. If Irene saw her with a hat and coat on, carrying her pocketbook, she would have a hard time explaining. She turned toward Main Street. With only 3¢, she couldn’t even go to a show.

She walked along slowly, and nobody paid any attention to her. She went in all the stores—the grocery, hardware, variety, department, dime store, in all of them. She looked at things for sale and thought what she would like to buy if she had a little money. The worst thing about living with Mama Hattie was never having any money to spend.

Why couldn’t she get a job at a store, selling things? That would be fun. She asked a clerk at the dime store about it. This clerk had sold her many things in the past and she looked upon her as a friend. But now the clerk frowned and said: “You’re too little. You have to be sixteen. And besides, they don’t hire colored people for clerks here. They’ve got a colored boy who scrubs the floor at night after we close up.”

Lula Bell’s heart sank. She had never thought of it before. None of the stores on Main Street had colored clerks. They were all white. The stores were closing now. The man in the dime store hustled her out. It was getting dark. A chilly north wind was blowing. She buttoned her coat.

Suddenly she thought of Miss Lena Patton and her store on Hibiscus Street. She had never thought of Miss Lena as a prospective employer before. She had hated Miss Lena and teased her and thrown chinaberries at her and called her names, but she had never before wanted Miss Lena to do her a personal favor. She made up her mind to go quickly and ask her for a job.

Miss Lena did not close up at six like the Main Street stores did. She even left her store open while she went in her house next door to eat her supper. She often stayed open until nine or ten o’clock—as long as her customers wanted anything. From 7 A. M. until 10 P. M. was too long a day for any woman. Lula Bell would tell her that. Miss Lena was getting old now. She must be forty already. She needed an assistant. Lula Bell walked back down Hibiscus Street and came to Miss Lena’s store.

Miss Lena stared at Lula Bell’s suitcase and pocketbook.

“Goin’ somewheres, girl?” she asked.

“No ma’m,” said Lula Bell.

“What you want?” Miss Lena asked. “Bread?” She laughed and added: “Without salt?”

But Lula Bell was in no mood for jokes. She was never more serious in all her life.

“I’d like … I’d like to work in your store, Miss Lena,” she blurted out. “I could come in after school and clerk while you’re out to supper.”

“You could, could you?” Miss Lena looked down her long nose at the girl. “You got big ideas since you been up north, ain’t you, girl? I reckon you think you could eat all the candy you want, and hand out a lot more to all the fifty kids on the street. No, girl, I still got a little sense.”

“I could sweep the floor and wait on customers and make change,” said Lula Bell meekly.

“How old are you, girl?” asked Miss Lena.

“I’m ten goin’ on eleven,” said Lula Bell. “My birthday’s next month.”

“Come back in five years and I’ll think about it,” said Miss Lena.

Lula Bell stepped quickly out on the sidewalk. It was dark now, and darkness enveloped her, body and soul. She was more unhappy than she had ever been in her life. She stood in the middle of the street uncertainly.

She’d have to go back, she knew that. She couldn’t run away, she couldn’t get a job. She’d have to go back and be Mama Hattie’s girl again. She’d have to be bossed around and told what to do and what not to do. She’d have to go and live with her grandmother. Her parents were off up north—they had deserted her. They did not care what happened to her. Home—Mama Hattie’s rickety old house was the only home she had. She’d have to go back.

Well, she wouldn’t tell anybody where she had been or what she had done. It was her affair, not theirs. She would keep her mouth shut. She would not talk to anybody.

Strengthened by a resolution to get it over with quickly, she marched in the front door. They were all sitting in the front room talking—Uncle Jim and the Bradleys, Mama Hattie and the boys. She went through without saying a word, her chin sunk low on her breast. Before she closed the bedroom door behind her, she heard Lonnie say with a laugh: “Well—the cat came back!”

It was cruel. It was a mean thing to say. She hated Lonnie, and she hated the whole world. She sank down on the bed and had a hard, silent cry. In the darkened room, she stifled her sobs in the pillows, so they would not hear her. In a short time the passionate storm was over and she got up. She turned on the light, unpacked her suitcase and hung up her clothes under the curtain in the corner. She found a nail and hung up the new looking glass. She was standing in front of it, staring at her reflection, when Mama Hattie came in.

“I thought you was takin’ the bus and goin’ back up north,” said Mama Hattie gently.

Lula Bell did not answer. All her anger was spent now. She felt only sadness. A big lump was in her throat.

They both began to undress. The room was very quiet. Lula Bell sat on the edge of the cot and kicked off her shoes. Her back was toward her grandmother and she faced the wall.

“You didn’t even care when I went away,” she said at last.

“Of course I cared,” said the old woman. “My heart ached for you. But I thought you should have a chance to see how hard life is, when you are all alone out in the world. You learned a lot in four short hours. I knew you would come back.”

“Comin’ back was harder than goin’ away,” said Lula Bell. “I was so mad then.”

“You ran away once when you was about four,” said Mama Hattie. “You ran around the house, and under every open window you stopped and called out: ‘I’m runnin’ away now.’ You wanted me to say, ‘Oh please come back,’ but I didn’t. I wanted you to be ready to come back—before you came.”

Lula Bell jumped up from the cot. She ran to her grandmother’s arms. Mama Hattie kissed her and held her close. They sat down on Mama Hattie’s bed.

“I won’t run off and leave you again,. Mama Hattie,” said Lula Bell. “I’ll stay here and take care of you.” She cried a little and Mama Hattie wiped the tears off her cheeks with her nightgown.

Lula Bell got up and went over to the new looking glass. She looked in and studied her own face. “Rose Marie said I’m almost as light as a white girl,” she announced.

“Who’s Rose Marie?” asked Mama Hattie.

“My girl-friend … in school up north,” said Lula Bell. “A white girl. She said I look sort of Spanish.”

Mama Hattie did not say anything.

“I wish I wasn’t colored,” Lula Bell went on. “I liked those white girls in my school.”

“So that’s what’s botherin’ you,” said Mama Hattie. “Come, stop lookin’ at yourself and crawl in bed here with me. Turn out that light. I’m glad you are here with me now—and not off somewheres alone.”

Lula Bell got in the big bed. She felt warm and contented, secure in her grandmother’s love, as she listened to her soothing voice.

“You may as well be proud to be a Negro,” said Mama Hattie. “You can’t pretend to be something else when you’re not. You have to be what you are, what the good Lord made you, and you might as well be satisfied.”

“Rose Marie said colored people are bad and tough and are always makin’ trouble,” said Lula Bell.

“There’s good and bad people, both colored and white,” said Mama Hattie, “but most people are good. Even the bad ones have good in them, though sometimes it’s hard to find. There’s a few bad ones in both races that cause most of the trouble. There’s nothin’ better in this world than a good colored woman, and that’s what I want you to be. You’re growin’ up fast now, and there’s lots of things you got to try to understand. I’ll help you all I can.” She paused, then went on. “Maybe that’s why the Lord didn’t take me when I was so sick, all ready to go. He still had work for me to do—to help you to git growed up and make a fine woman out of you.”

Her voice died away into the silence of the room.

“Mama Hattie, that was Daddy Joe’s money I used to buy my lookin’ glass,” confessed Lula Bell. “I didn’t take a penny outa your pocketbook.”

“That’s good, honey,” said Mama Hattie sleepily. “Why didn’t you say so?”

* Courtesy of Robert Music Corporation.