CHAPTER XI

“Lula Bell! Lula Bell!”

The girl turned over in bed, then she heard it again.

“Lula Bell! Lula Bell! Git up and light the fire in the kitchen stove.” It was Mama Hattie’s voice. “Put the teakettle of water on to heat. I can’t git up—I’s got a misery in my back this mornin’.”

Lula Bell rose sleepily and stumbled to her feet.

“Don’t leave the burner turned up too high,” said Mama Hattie.

Lula Bell paddled out to the kitchen, and the linoleum was cold on her bare feet. She found a match, turned on the kerosene and lighted the stove. She filled the kettle with water at the sink, and set it on the burner. She stumbled back to her bed. She and Mama Hattie were soon sound asleep again.

“Miss Hattie! Miss Hattie! Where you at? Come quick!” A man’s voice resounded through the small house.

“Who that? Who callin’?” The old woman raised herself on her elbow. “There’s a man in the house! What do I smell? Somethin’s happened … Go quick, Lu-Bell, see what’s the matter. What you close the door for? Oh Lordy, I can’t even git outa bed. I’m stiff in every blessed joint.”

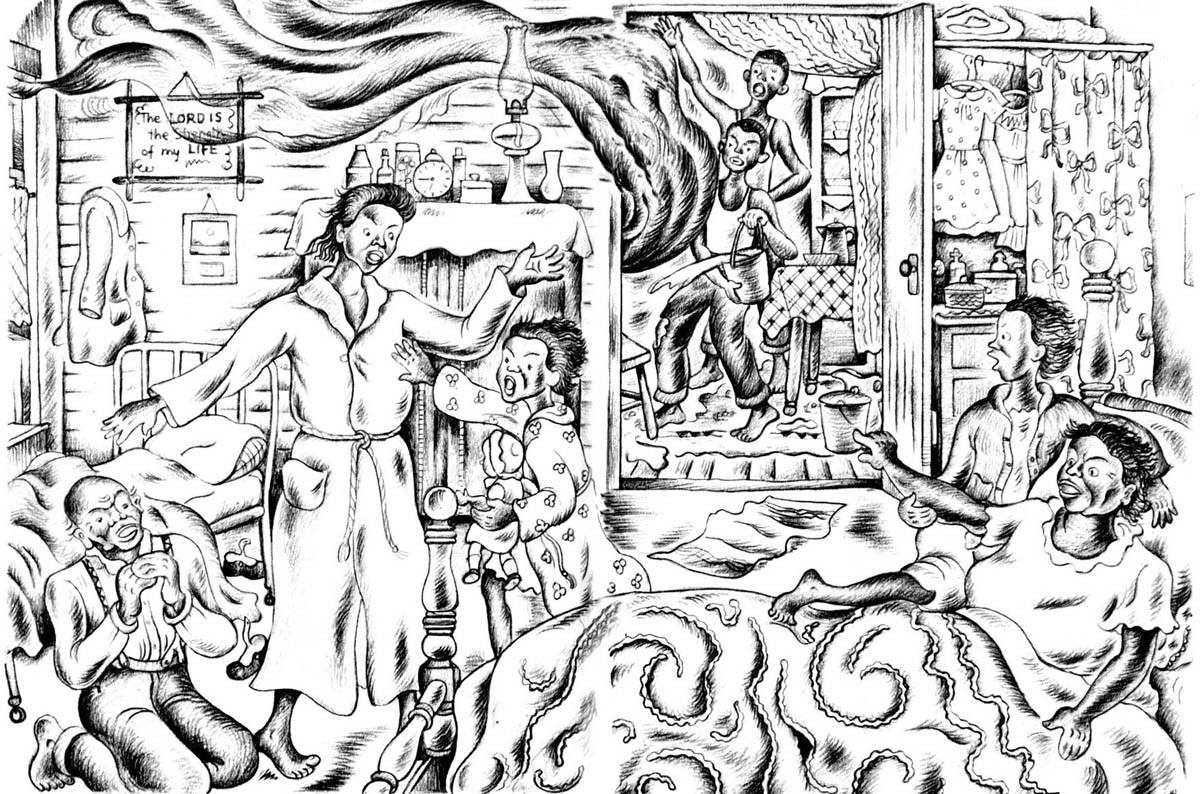

Loud thumps and shouts came from the kitchen. More voices could be heard, Miss Vennie’s, Uncle Jim’s and the boys’. Lula Bell pulled on a sweater and threw open the door. The kitchen was filled with black smoke.

“The house is on fire!” screamed Lula Bell. “The house is burnin’ up!”

The kerosene stove was enveloped in flames, reaching to the ceiling. Andy Jenkins was there with a bucket, throwing water, trying to put the fire out. Lonnie and Eddie filled cooking pots with water at the sink. They threw the water on the walls to keep them from catching fire.

“Oh Lordy!” groaned Mama Hattie. “The house on fire and me so lame in bed I can’t even raise myself up. Help me, Lula Bell. Help me to git up …” Lula Bell tried to raise her, but her grandmother’s body was a dead weight. “No, I’ll jest stay here,” said Mama Hattie. “I mustn’t git excited or my heart will act up. Oh Lord, help Mr. Andy and the boys to put the fire out, so I won’t burn up in my bed.” She began to moan and cry and pray. “‘Oh Lord, hear us when we cry to Thee …’”

Lula Bell looked into the kitchen, and her cries were mingled with her grandmother’s.

“Miss Hattie! Miss Hattie!” Vennie Bradley rushed into the bedroom, with little frightened Myrtle clinging to her bathrobe. “The house is afire! The house is burnin’ up. What we gonna do? Where we gonna go?”

Miss Hattie began to give orders. “Go save your clothes and the furniture. Go, set everything out in the yard. Go, phone the fire department, somebody. Tell ’em to come quick. Lula Bell, carry all our clothes outside. Save the radio, save the settee, save my electric washer …”

“What’ll I take first?” asked Miss Vennie, bewildered.

“Lord, save us! Lord, save us!” prayed Uncle Jim.

“Go on back to your room and git dressed,” called Lonnie. “The fire’s out. Mr. Andy and us boys put it out. ’Twas only the kerosene stove flarin’ up.”

“Lucky you come runnin’ in, Mr. Andy,” said Eddie. “You come jest in the nick of time.”

“‘The Lord is good and His mercy is everlasting …’” prayed Uncle Jim in a loud voice.

“When I come out on my doorstep ’fore day,” said Andy Jenkins, “I seen Miss Hattie’s house in flames. Right through the glass in the front door I seen flames a-rarin’ right up to the ceiling, and nobody knew it ’cause you-all was fast asleep. I busted the lock right open and in I come …”

“We shore do thank ye, Mr. Andy,” called Miss Hattie from her bed.

Andy opened the door and windows to let the smoke out, then went back to his tavern across the street. Out in the kitchen, Lula Bell stared at the damage. Walls and ceiling were charred black, and so was the white enamel on the end of the stove. The teakettle was coal black too. The sight made her feel sick. She sat down at the foot of Mama Hattie’s bed.

“I always was afraid my old oil stove might explode,” said Mama Hattie, “and set the house afire. I never thought this purty new one would do it.”

“It’s ruined now,” said Lula Bell. “It’ll never be white and purty again.”

“The enamel’s spoiled?” asked Mama Hattie.

“It’s burnt plumb black across the end,” said Lula Bell.

“The man I bought it from said that enamel would last a lifetime,” said the old woman. “Ruined already and not half paid for. $7 a month to pay, and I still owes $70 on it.”

“I left it turned too high,” said Lula Bell, crying again. “I was so sleepy, I forgot to turn it down.”

“I ain’t a-blamin’ you, honey,” said Mama Hattie. “It coulda happened to anybody.”

Lula Bell went to school without any breakfast that morning, and she had only a dime for a sandwich at noon. After school, she went on some errands with Geneva Jackson, so it was nearly dark when she came in. Before she entered the door she smelled fried fish. The smell made her hungrier than ever.

“Yummy! Fish for supper!” she cried happily. “Somebody musta fixed the stove. Do it burn all right?”

Miss Vennie was at the stove instead of Mama Hattie. She was frying fish in deep fat. She had a great platter already piled high.

“Huh! Your fish, I suppose!” said Lula Bell.

“There’s plenty for everybody,” said Miss Vennie, unexpectedly gracious. “Lonnie and Eddie went fishin’ after school and caught us a big mess.”

“I thought the stove was ruined,” said Lula Bell.

“No,” said Miss Vennie. “Mr. Andy cleaned the burner out and put in a new metal chimney and wicks. It burns O. K. again.”

The boys came in and Miss Vennie put the fish on the table. She had fixed creamed potatoes and English peas too. Lula Bell sat down and ate.

“Gee! This is good,” she said. She looked at Miss Vennie. “Why, you’re a good cook!”

Miss Vennie tossed her head. “Of course. Why not? I been cookin’ all my life.”

All of a sudden Lula Bell thought of her grandmother. The bedroom door was closed tight. “Where’s Mama Hattie? Why didn’t she cook supper?”

“She’s sick,” said Miss Vennie. “She ain’t been up all day. That fire seemed to take all the life and spirit right out of her. She’s coughin’ again and she don’t want to eat.”

“Her blood’s high, I bet,” said Lula Bell. Looking at Miss Vennie, she asked, “What we gonna do if Mama Hattie gits sick on us?”

Miss Vennie turned her back, took little Myrtle by the hand and left the kitchen. “I’m sure I don’t know,” Miss Vennie called back. “She’s not my grandmother. She’s no kin o’ mine.”

“You’re not helpin’ with the dishes, Miss Vennie?” called Lula Bell in a pleading voice. “After we let you eat our fish?”

The front bedroom door went shut with a sharp thud. That was the answer she got. “Well, of all things!” cried Lula Bell.

Lonnie and Eddie ran outdoors to escape being called. There was no one to do the dishes but Lula Bell. Peeping in the back bedroom, she saw that Mama Hattie was asleep, so she could not ask her help. Besides she was sick.

It took a long time to get the dishes done. Miss Vennie had fried the fish, but she had not scoured the soot off the teakettle, nor tried to clean the end of the stove. It took still longer to do that. After she was all done, Lula Bell went in the front room to turn the radio on for a while before going to bed. She went to the corner where she had hung her new looking glass on the wall. She wanted to take a look at herself. The looking glass was not hanging on its nail. There at her feet she saw it, broken into pieces on the floor.

“Look at that! Who done it? Who busted my lookin’ glass?”

Lula Bell ranted and raged, accusing every one. She knocked briskly on the closed door of the Bradleys’ room. Myrtle and Miss Vennie came out in their bathrobes.

“Who been messin’ around here?” demanded Lula Bell. “Who tried to steal my lookin’ glass and dropped and broke it?”

Myrtle clung to her baby-doll and did not answer.

“Did you break it?” Lula Bell grabbed the girl by the arm and began to shake her. “You may as well admit it, girl. I know you done it.”

“You know a lot, don’t you?” replied Miss Vennie.

Suddenly there stood Mama Hattie on tottery feet at the door. “How do you know she broke it? Did you see her do it?” she asked.

“No ma’m,” admitted Lula Bell, “but there’s been nobody else around. It musta been her. Miss Vennie can jest buy me a new one.”

“Myrtle never touched your little ole lookin’ glass,” said Miss Vennie, “and I didn’t neither.” Pulling Myrtle back into her room, she closed the door sharply.

“See what you done?” cried the old woman. “You’ve made her mad. Remember what I told you about makin’ trouble with my boarders. If Miss Vennie leaves, it will be your fault. Don’t ever accuse innocent people of breakin’ your lookin’ glass. It don’t matter who done it. It’s bad enough it got broke. It means seven years bad luck—that’s what it means.”

“You’ll make Miss Vennie buy me a new one, won’t you?” begged Lula Bell.

“No, girl, I sure won’t,” said Mama Hattie.

Mama Hattie’s cold grew worse. For the next three days she stayed in bed. Miss Vennie kept to her room, did her own cooking and did not offer to help. Lula Bell cooked for herself and the boys, and fixed what little her grandmother wanted. Lonnie opened cans for her, and if she begged hard enough, the boys washed the dishes.

On the second day, Lula Bell stopped at Aunty Irene’s house cross-town, on her way home from school. Aunty Irene would not let her come in. She talked to her out of an open window.

“Measles!” she said. “Three little ones down sick, and Dora will be next. I have to watch ’em like a hawk or they’ll pull the shade up and git the light in their eyes. I wish I might could come and help you, but I can’t right now.”

“What’ll I do?” asked Lula Bell.

“Do what you can,” said Aunty Irene. “Make the boys help. Mama Hattie will shake off her cold soon. She won’t stay in bed long.”

“I think I’ll phone to Aunty Ruth,” said Lula Bell.

“Oh no, that costs too much,” said Irene. “We don’t want to worry her and Imogene unless Mama gits real bad.”

Lula Bell came back home discouraged. There was no help to be had from Aunty Irene. She’d have to depend on herself. She’d have to stay home from school, there was so much to do.

It was hard for her to watch Myrtle go marching off to school each morning, dressed in a pretty gingham dress. It was harder still to see Geneva Jackson and Floradell Pearson run past the house without calling for Lula Bell, and join up with Myrtle halfway down the block. Lula Bell could not believe her eyes. She could not believe that her best friends could be so disloyal. It made her dislike little Myrtle more than ever. Myrtle did not have to stay home from school and take care of a sick grandmother and do a family washing. All Myrtle did at home was play with her little old baby-doll.

Lula Bell looked at the dirty clothes piled up in the clothes-basket. Somebody ought to wash them.

“How about you doin’ it?” suggested Mama Hattie from her bed. “It’s not hard work with the electric washer. You can wring ’em by hand. I won’t let you touch that wringer.”

Lula Bell did the washing alone for the first time in her life, and felt very sorry for herself. When she started on the ironing in the front room, Miss Vennie came out and surprised her. “Can I help?” she asked.

Lula Bell tossed her head. “No ma’m!” she cried. “I’m gittin’ along first-rate by myself.”

“O. K.,” replied Miss Vennie. “Don’t say I didn’t offer.”

Mama Hattie’s cold improved as the weather turned warmer. Instead of lying in bed, she asked to sit on the porch. Still weak and tottery, she walked outside with her hand on Lula Bell’s shoulder. Whenever she exerted herself, her heart began to act up. So she had to sit very still. Her friends went past and called and waved to her, but Miss Hattie did not look up. She was too tired.

Each day she stayed out all day. The house faced the south, so she was partly in the sun and seemed to enjoy it. Lula Bell combed her hair as she sat there. She platted it in two braids and pinned it across the top.

“Now you look like a queen, Mama Hattie,” said Lula Bell.

“A sorry queen.” Mama Hattie smiled a little.

“I knew a girl up north whose name was Queen Esther,” said Lula Bell.

“That’s a good name,” said Mama Hattie. “It’s from the Bible.”

“She wasn’t a very good girl,” said Lula Bell. “She was mean.”

Lula Bell brought all the old woman’s meals out to her on the porch. She took a basin of warm water out, and washed her feet there. Sometimes Mama Hattie let her feet soak in the water. “It rests ’em,” she said. “My feetses is so tired. They’ve walked so many miles …”

“But what if somebody saw you!” cried Lula Bell. “Wouldn’t you be ashamed?”

“You sound like Imogene,” said Mama Hattie. “Why should I be ashamed of my feetses? The good Lord gave ’em to me. He gave me this ole heart too, but it’s ’most wore out.”

“But I’d be ashamed,” said Lula Bell. “I wouldn’t want the girls to see me washin’ your feet.”

“In church on Love Feast Day, we washes each other’s feetses,” said Mama Hattie, “jest like it say in the Bible. Do you know who tole us to do that, and who done it first? Jesus. We tries to follow His example. We tries to do what He told us to.”

Just then Lula Bell saw the school children coming down Hibiscus Street, on their way home from school.

“Gimme that basin, quick,” she said. “I don’t want nobody to see it out here. Put on your slippers, Mama Hattie.”

But Lula Bell need not have worried. The children never even looked in her direction. The little ones began a game of hide-and-seek. The older girls came walking along slowly, arm-in-arm. Lula Bell emptied the basin, then stood leaning against the porch post, hoping they would call to her. But they didn’t. She looked and saw the reason why. Geneva, Floradell and Josephine were huddled in a circle, with Myrtle Bradley in the middle.

“Well, I’ll be …!” Lula Bell was so furious she didn’t know what to say.

“What’s the matter?” asked Mama Hattie listlessly.

“Plenty’s the matter,” said Lula Bell under her breath. “Jest look out there and see.”

“Who is it? The mail man? Is he bringin’ me a letter from Imogene?” asked the old woman. “I don’t like that job she’s got. A bookkeeper or a sec’tary or somethin’. On my radio program, all the sec’taries is crooks. I want you to write a letter to Imogene and tell her to git a new kind of job.”

Lula Bell did not hear what her grandmother was saying. She stood and watched as Myrtle began to teach the girls how to play My Bread Is Burning. The little children joined in, and soon Hibiscus Street echoed with their shouts and laughter.

“Go on over and play with ’em a while,” said Mama Hattie. “You been workin’ hard all day. It’ll do you good.”

“O. K.,” said Lula Bell. “I’ll go but I’ll not play.” Under her breath she added: “I’ll give those girls a piece of my mind. What do they think they’re doin’, anyhow—makin’ up to that miserable little Myrtle?”

Lula Bell rushed across the street, with her firsts doubled up and her blood boiling. She came closer and closer, and was about to say what she thought of her former friends. Then she saw that the circle of friendship was closed to her. Myrtle was inside and she was out. Floradell saw Lula Bell coming. She leaned over and whispered to the others: “Don’t let her in. We don’t want her. Don’t let her in.”

The children held hands so tightly that, try where she would, she could not break the circle.

Then Floradell shouted some mystic word—a new word that Lula Bell had never heard before and of which she did not know the meaning. At the sound of it, all the children dropped hands and ran. In a moment they were gone, hidden from sight behind hedges and houses.

Only one was left—Lula Bell—standing alone in the middle of the street. A sob broke from her lips. Hurt to the quick, she ran swiftly home.