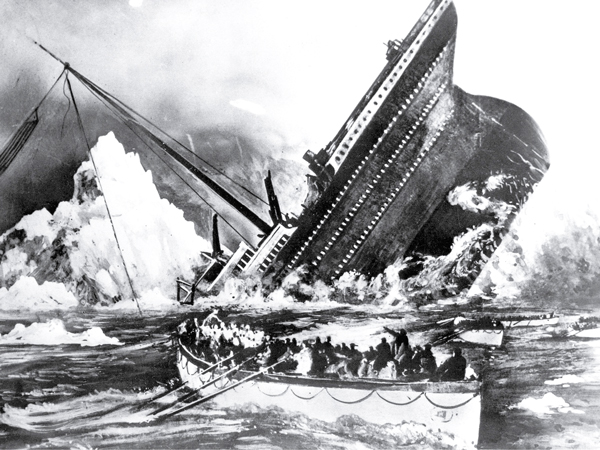

(Preceding image) Artists at the time of the disaster imagined the sinking in dramatic illustrations, not always accurate. Here, the Titanic’s stern rises into the air as the ship goes down; lifeboat passengers can only look on.

“I almost thought, as I saw her sink beneath the water, that I could see Jacques, standing where I had left him and waving at me.”

— May Futrelle

“We could see her very plainly, badly down by the head,” said Frankie Goldsmith. “All the lights seemed to be on when suddenly they all went out, and a loud explosion was heard.”

Frankie and his mother had escaped in Collapsible C, one of the last lifeboats. Once on the water, Frankie’s mother tried to keep him from looking back at the ship, forcing his head down so that he couldn’t see. Then some of the ladies in the lifeboat cried out, “‘Oh, it’s going to float!’

“Mother then released me, and now beginning to be fearful about my father, I lifted myself to look past her shoulder and saw the tail end of our ship aimed straight up toward the stars in the sky,” said Frankie.

“It seemed to stay that way for several minutes. Then another slight noise was heard, and it very slowly began to go lower . . .”

Lawrence Beesley, safe in a lifeboat, struggled to describe the sounds of the dying ship. “It was partly a roar, partly a groan, partly a rattle, and partly a smash . . . it was a noise no one had ever heard before, and no one wishes to hear again: it was stupefying, stupendous, as it came to us along the water,” he wrote.

“When the noise was over the Titanic was still upright like a column: we could see her now only as the stern and some 150 feet of her stood outlined against the star-specked sky, looming black in the darkness, and in this position she continued for some minutes . . .” he went on. “Then, first sinking back a little at the stern, I thought, she slid slowly forwards through the water . . .”

Charles Lightoller watched the final moments of the Titanic from his precarious perch on Collapsible B.

When the lights went out, “. . . the huge bulk was left in black darkness, but clearly silhouetted against the bright sky. Then, the next moment, the massive boilers left their beds and went thundering down with a hollow rumbling roar, through the bulkheads, carrying everything with them that stood in their way.”

He knew the end was near. “The huge ship slowly but surely reared herself on end and brought rudder and propellers clear of the water till, at last she assumed an absolute perpendicular position. In this amazing attitude she remained for the space of half a minute. Then . . . she silently took her last tragic dive to seek a final resting place in the unfathomable depth of the cold gray Atlantic,” he said.

Around him everyone breathed two words, “‘She’s gone.’”

It was 2:20 a.m.

When Colonel Archibald Gracie turned around to look for the ship, he realized that the Titanic was nowhere to be found. The strange sound he had heard must have been the water closing over the stern in those last seconds.

Near him, three men floated facedown. A little farther away, he could hear the last, desperate cries of others who had tumbled into the sea.

Colonel Gracie knew he would soon lose his own battle. He threw his leg over the wooden crate to try to get his body out of the frigid water. It didn’t work. He ended up doing a somersault under the surface.

A shape in the distance caught his eye. It was one of the collapsible boats, upside down, with what seemed to be a dozen or so men on top of her. It was far, but he didn’t stop to think if he could make it or not. He set out.

When Gracie reached the boat, he grabbed the arm of a crew member and pulled himself up. He lay on the upturned bottom, gasping and shivering.

A tremendous sense of relief washed over him. “I now felt for the first time . . . that I had some chance of escape from the horrible fate of drowning in the icy waters of the middle Atlantic.”

High-school student Jack Thayer had barely escaped being hit when the second funnel crashed into the sea. When he surfaced, Jack found himself near Collapsible B, and somehow managed to pull himself up and hold on for dear life.

Jack felt as though hours had passed since he’d left the ship, though he knew it was probably only about four minutes. From his perch on the bottom of the lifeboat he witnessed the ship’s last moments, as the stern rose — and then sank down into the sea.

At first it was quiet. Then, there came a cry for help, and then another. It soon became “one long continuous wailing chant, from the fifteen hundred in the water all around us . . . This terrible continuing cry lasted for twenty or thirty minutes, gradually dying away, as one after another could no longer withstand the cold and exposure. . . .”

Jack was struck with horror when he realized that no one was answering these cries. The lifeboats were not returning.

“The most heartrending part of the whole tragedy was the failure, right after the Titanic sank, of those boats which were only partially loaded, to pick up the poor souls in the water,” said Jack. “There they were, only four or five hundred yards away, listening to the cries, and still they did not come back.”

Lawrence Beesley and his fellow survivors in Lifeboat 13 were shocked when they realized that so many people had been left behind to perish in the water.

“We were utterly surprised to hear this cry go up as the waves closed over the Titanic: we had heard no sound of any kind from her since we left her side . . . and we did not know how many boats she had or how many rafts,” said Lawrence. “. . . we longed to return and rescue at least some of the drowning, but we knew it was impossible.

“The boat was filled to standing-room, and to return would mean the swamping of us all, and so the captain-stoker told his crew to row away from the cries,” Lawrence later wrote. “We tried to sing to keep all from thinking of them; but there was no heart for singing in the boat at that time.”

In Lifeboat 6, a group of women led by Margaret Brown (later known to history as the “Unsinkable Molly Brown”) urged Quartermaster Robert Hichens to return to pick up people in the water. He refused, although later he denied it.

First class passenger Major Arthur Peuchen had been allowed into this lifeboat to help row, since he was an experienced yachtsman. He was disgusted with the quartermaster’s behavior. “. . . we all thought we ought to go back to the boat. . . . But the quartermaster said, ‘No, we are not going back to the boat. . . . It is our lives now, not theirs,’ and he insisted upon our rowing farther away.

“He said it was no use going back there, there was only a lot of stiffs there . . . which was very unkind, and the women resented it very much.”

In contrast to Hichens, Fifth Officer Harold Lowe had been busy organizing a rescue plan from the moment his lifeboat had touched the surface of the ocean. He began by transferring passengers from Lifeboat 14 into other lifeboats before going back with a near-empty boat to pick up survivors.

Joseph Scarrott recalled how Fifth Officer Lowe took charge of four other lifeboats, moving passengers to make room to rescue survivors from the water.

“Mr. Lowe decided to transfer the passengers that we had . . . and go in the direction of those cries and see if we could save anybody else. The boats were made fast and the passengers were transferred, and we went away and went among the wreckage,” Scarrott later testified. “When we got to where the cries were we were amongst hundreds, I should say, of dead bodies floating in lifebelts.”

Lowe had made an awful mistake: He had waited too long. It was probably after 3 a.m. when he began searching.

As the lifeboat moved through the water, Lowe and Scarrott could find only four people still alive. They pulled them all into the boat, but one, first class businessman William Hoyt, later died. The lifeboat remained mostly empty.

Another boat also picked up survivors that night. Lifeboat 4, with quartermaster Walter Perkis in charge, returned to the area where the ship had gone down and rescued eight people, although two of them died. This lifeboat carried Marian Thayer, Jack Thayer’s mother; Madeleine Astor, wife of the millionaire John Jacob Astor IV; and Emily Ryerson and her three children, including her 13-year-old son, Jack, who had almost been turned away.

A bit earlier, as the ship was sinking, Lifeboat 4 had plucked someone else from the water: Sam Hemming, the seaman who’d been cheerfully helping Second Officer Lightoller to launch lifeboats almost to the last.

As the water was coming over the bridge, Sam had looked to see if he could spot any lifeboats. Off the starboard side, everything was black. But two hundred yards away on the port side he saw a boat. He slid down the side of the ship and struck out for it — without a life preserver.

When he reached it, Sam called out to Jack Foley, a fellow crew member he recognized. “‘Give us a hand in, Jack.’

“He said, ‘Is that you, Sam?’ I said, ‘Yes,’ and him and the women and children pulled me in the boat.”

Later, Sam Hemming was questioned by Senator William Smith, who seemed to have a hard time believing that the seaman had accomplished such an incredible feat. “Do you mean to tell me that you swam from the Titanic two or three hundred yards? . . . Two hundred yards without a life preserver on?” he inquired.

Sam Hemming assured him that he had. He had a life preserver in his room, but had never had time to go back for it.

Sam also told the senator that the water was cold. Very cold. “It made my feet and hands sore, sir.”

Meanwhile, less than twenty miles away, the Californian slumbered on.

Later, crew members on the Californian reported that when they no longer saw the Titanic’s lights, they simply assumed that the unknown ship in the distance had sailed away.

Nothing could have been further from the truth.

Over the next minutes and hours, as a result of cold, exposure, and drowning, 1,496 men, women, and children would perish.

Mr. Lowe: . . . I chased all of my passengers out of my boat and emptied her into four other boats that I had. I herded five boats all together.

Senator Smith: Yes; what were they?

Mr. Lowe: I was in No. 14. Then I had 10, I had 12, and I had another collapsible, and one other boat the number of which I do not know. I herded them together and roped them — made them all tie up — and of course I had to wait until the yells and shrieks had subsided — for the people to thin out — and then I deemed it safe for me to go amongst the wreckage.

So I transferred all my passengers — somewhere about 53 passengers — from my boat, and I equally distributed them between my other four boats. Then I asked for volunteers to go with me to the wreck. . . .

Then I went off and I rowed off to the wreckage and around the wreckage and I picked up four people.

Senator Smith: Dead or alive?

Mr. Lowe: Four alive.

Senator Smith: Who were they?

Mr. Lowe: I do not know.

Senator Smith: Have you ever found out?

Mr. Lowe: I do not know who those three live persons were; they never came near me afterwards, either to say this, that, or the other. But one died, and that was a Mr. Hoyt of New York, and it took all the boat’s crew to pull this gentleman into the boat, because he was an enormous man, and I suppose he had been soaked fairly well with water, and when we picked him up he was bleeding from the mouth and from the nose.

So we did get him on board and I propped him up at the stern of the boat, and we let go his collar, took his collar off, and loosened his shirt so as to give him every chance to breathe; but, unfortunately, he died. I suppose he was too far gone when we picked him up. But the other three survived. I then left the wreck. I went right around and, strange to say, I did not see a single female body, not one, around the wreckage.