(Preceding image) An anxious crowd gathers outside the London offices of the White Star Line, seeking news of the Titanic.

“The final docking in New York at Pier No. 54 North River, when all our friends and relations learned the truth about the extent of the loss, was the last nerve-shattering blow for many people . . . it marked the end of all hope.”

— Jack Thayer

On Tuesday morning, April 16, the headline on the front page of the New York Times broke the first news of the tragedy: “Titanic Sinks Four Hours After Hitting Iceberg.”

The Times had gotten hold of wireless telegraph reports of the Titanic’s distress signals on Monday night. A new age of immediate media coverage was ushered in; the reputation of the New York Times as a major national newspaper grew, thanks to its early breaking of the story and coverage of the event.

By the time the Carpathia docked in New York on Thursday evening, April 18, intense interest in the disaster had spread worldwide. Newspapers issued special editions. White Star offices were crowded with people eager for news. The flags of all ships in New York Harbor were flown at half mast.

As the Carpathia glided toward Pier 54, she was surrounded by tugs. Reporters shouted out questions. More than 30,000 people waited in the rain, huddled under black umbrellas. Police had strung ropes to allow the survivors to pass. The usual customs inspections didn’t take place.

Souvenir hunters were already out in full force. On Thursday night, people stole oars and equipment from the Titanic’s lifeboats, which had been unloaded from the Carpathia. But interest in Titanic memorabilia had begun even earlier. James and Mabel Fenwick, a honeymoon couple on board the Carpathia, discovered a hardtack biscuit in a Titanic lifeboat and kept it, passing it down as a family keepsake.

Colonel Archibald Gracie regretted not keeping his life belt. After moving from Collapsible B into Lifeboat 12, he huddled under a steamer rug with other passengers before reaching the rescue ship.

“My life-belt was wet and uncomfortable and I threw it overboard . . . I regret I did not preserve it as a relic,” said Gracie.

Perhaps he should have. Genuine souvenirs of the Titanic have only increased in value over time. Christie’s auction house has sold a brass name plate from one of the Titanic’s lifeboats for $60,000, while just a fragment from a life belt has fetched more than $11,000.

(Preceding image) The April 16, 1912, headline of the New York Times announces the sinking of the Titanic.

Survivor Lawrence Beesley was very glad to see land again. It seemed to him that eight weeks rather than eight days had passed since he’d left England. He could barely remember those first peaceful, uneventful hours of the voyage.

And, even then, he understood that his life would never be the same. “I think we all realized that time may be measured more by events than by seconds and minutes: what the astronomer would call 2:20 a.m. April 15, 1912, the survivors called ‘the sinking of the Titanic,’” he said.

What Lawrence couldn’t know was that a century later, even after all survivors had passed away, people around the world would still remember this date and time, and continue to commemorate the sinking of the Titanic.

(Preceding image) Crowds gather in New York City to read the bulletin board of the New York American to learn about the disaster of the Titanic.

(Preceding image) A huge crowd forms outside the New York City offices of the White Star Line, awaiting news of the Titanic.

(Preceding image) A newsboy sells the Evening News announcing the sinking of the Titanic.

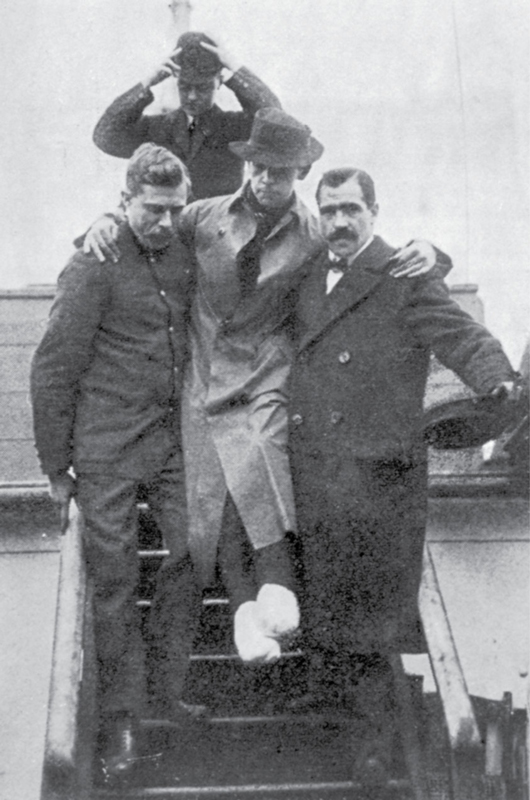

Harold Bride had played a key role in the Titanic’s efforts to get assistance from other ships. When the Carpathia arrived in New York, he found himself at the center of the media’s interest. He sold his story to the New York Times and was happy to receive the money.

It would take Bride until the end of April to begin to feel better. By then he could say, “I am glad to say I can now walk around, the sprain in my left foot being much better, though my right foot remains numbed from the exposure and cold but causes me no pain [or] inconvenience whatever.”

Harold Bride returned to England. He never forgot the dedication of Jack Phillips, who had continued at his post sending distress signals until the very end. Bride married and moved to Scotland. He and his wife had three children.

They named one of them Jack.

(Preceding image) Wireless operator Harold Bride suffered badly injured feet in the Titanic disaster.

Although she knew in her heart it was unlikely, stewardess Violet Jessop couldn’t help holding out hope for a miracle: that another ship had somehow picked up survivors.

“In the dusk of evening, we crept up the Hudson into New York, where a crowd waited, hoping against hope that messages received had been false and that relatives might be among those on board,” wrote Violet.

“Long before we got near the dock, despairing inquires were shouted across the intervening waters. It was only then that we learned that no other ship had found a soul. The horror was renewed all over again.”

The next day, recalled Violet, some people brought used clothing they’d collected to the dock and spread the items out on tables for survivors. It reminded her of a rummage sale. Her thoughts were on getting back home, though it was hard to face another voyage at sea.

Violet Jessop went back to Great Britain on the Lapland, on a more southerly route than the Titanic had taken. Two weeks after the British inquiry into the Titanic disaster, Violet Jessop was on another ship — back on the job.

The Titanic was not the only maritime disaster Violet survived. During World War I, she served as a volunteer nurse for the British. Exhausted and sick after a tour of hospital duty, she was assigned to sea duty on board the Britannic, sister ship of the Titanic.

Violet was on board on November 21, 1916, when the hospital ship struck a mine off the Greek island of Kea and sank in fifty-five minutes, with the loss of thirty lives. Violet was nearly killed by the ship’s propellers when she jumped into the sea from her lifeboat. She had never been underwater before and could not swim. Her life jacket came loose and couldn’t support her. She managed to grab another life belt floating nearby. Before her eyes the ship took its final plunge.

Violet Jessop was pulled from the water by another lifeboat. She returned to work for the White Star Line in 1920, serving on the Olympic, where she had once been a stewardess before joining the Titanic. She continued at sea until she retired in 1950.

Brooklyn, New York

Sun April 21

My dear Mother and all,

I don’t know how to write to you or what to say, I feel I shall go mad sometimes but dear as much as my heart aches it aches for you too for he is your son and the best that ever lived. I had not given up hope till today that he might be found but I’m told all boats are accounted for. Oh mother how can I live without him. I wish I’d gone with him if they had not wrenched Madge from me I should have stayed and gone with him. But they threw her into the boat and pulled me in too but he was so calm and I know he would rather I lived for her little sake otherwise she would have been an orphan. The agony of that night can never be told . . . I haven’t a thing in the world that was his only his rings. Everything we had went down . . .

Charlotte Collyer

Frankie Goldsmith and his mother, Emily, arrived in New York destitute. Although they only received fifteen dollars from the White Star Line and two railroad tickets to Detroit, other groups, including the Titanic Women’s Relief Committee and the Red Cross, provided financial assistance to them and other families in need.

Emily and her son kept in touch with several friends they’d met on the voyage, such as fireman Sam Collins and Rhoda Abbott, who had lost her two sons and was the only woman rescued from the water.

In a letter to Emily Goldsmith in early 1914, Rhoda Abbott wrote: “I read by the papers the terrible weather you are having. I suppose Frank enjoys it. I know my little fellow used to when he was alive. I have his sled now that he used to enjoy so much, bless his little heart. I know he is safe in God’s keeping, but I miss him So Much.”

As an adult, Frank Goldsmith continued to keep in touch with and search for other survivors of the disaster. He gave radio and television interviews on Titanic anniversaries, and was active in the Titanic Historical Society. When Frank passed away in 1982, his ashes were scattered in the North Atlantic, near the spot where his father had perished seventy years before.

The United States Senate lost no time in calling for an investigation of the Titanic disaster. After all, some of the wealthiest men of business and most prominent members of society had perished.

In the days from the first inkling of the tragedy until the Carpathia’s arrival in New York City, newspapers, families, and politicians had many questions. But above all there was disbelief: How could the world’s largest and safest vessel have sunk so quickly, with so much loss of life?

On Wednesday, April 17, 1912, Senator William Alden Smith proposed that an investigation be held under the Senate Commerce Committee. His Senate resolution called for a panel to be formed to “investigate the causes leading to the wreck of the White Star liner Titanic, with its attendant loss of life so shocking to the civilized world.”

Senator Smith boarded the Carpathia as it was docking on Thursday evening, April 18. He spoke to J. Bruce Ismay personally, to ensure that he and employees of the White Star Line would cooperate with the hearings that, incredibly, were begun the very next morning, on Friday, April 19, at the Waldorf-Astoria hotel in New York City. The first witness called was J. Bruce Ismay himself.

The United States inquiry was followed by one in Great Britain, which lasted until July. In the end, the British investigation, sometimes called the Mersey Commission since it was led by Lord Mersey (Charles Bigham), did not find either Captain E. J. Smith or J. Bruce Ismay guilty of negligence.

But in its final report, the commission made a number of recommendations for the future, including twenty-four-hour-a-day wireless operators on duty, frequent lifeboat drills, and, most important, that there should be enough lifeboats and seats in them for every person on board.

(Preceding image) The U.S. Senate Investigating Committee questions individuals about the Titanic disaster at the Waldorf-Astoria in New York City.

Colonel Archibald Gracie was an amateur historian. So it’s not surprising that he began talking with other survivors right away, even while they were still on board the Carpathia, to document the events of the disaster.

He noted in his book, originally published in 1913 as The Truth About the Titanic, that he felt an obligation to write about what happened.

“As the sole survivor of all the men passengers of the Titanic stationed during the loading of six or more lifeboats with women and children on the port side of the ship, forward on the glass-sheltered Deck A, and later on the Boat Deck above, it is my duty to bear testimony to the heroism on the part of all concerned. First, to my men companions who calmly stood by until the lifeboats had departed loaded with women and the available complement of crew . . .

“Second, to Second Officer Lightoller and his ship’s crew, who did their duty as if similar occurrences were matters of daily routine; and thirdly, to the women who showed no signs of fear or panic whatsoever under conditions more appalling than were ever recorded before in the history of disasters at sea.”

Sadly, the Colonel did not live to see his book come out. He suffered from diabetes, and the exposure he endured during the night the Titanic sank and the time he spent in the freezing seas led to a decline in his health. He died on December 4, 1912. Many Titanic survivors attended his funeral.

In reporting Colonel Gracie’s death the following day, the New York Times noted that, “The events of the night of the wreck were constantly on his mind. The manuscript of his work on the subject had finally been completed and sent to the printers when his last illness came. In his last hours the memories of the disaster did not leave him. Rather they crowded thicker, and he was heard to say:

“‘We must get them into the boats. We must get them all into the boats.’”

The Court, having carefully inquired into the circumstances of the above mentioned shipping casualty, finds, for the reasons appearing in the annex hereto, that the loss of the said ship was due to collision with an iceberg, brought about by the excessive speed at which the ship was being navigated.

Dated this 30th day of July, 1912.

MERSEY.

Wreck Commissioner.

(Preceding image) Surviving crew members of the Titanic wait to be called in for questioning by the board of inquiry.

The Titanic disaster shocked people all over the globe. Jack Thayer put it this way: “To my mind the world of today awoke April 15, 1912.” From that day on, the Titanic has continued to be part of popular culture, through fiction and nonfiction books, films, songs, undersea explorations, museum exhibitions, and the Internet.

The events of the Titanic disaster can be seen as a symbol of what happens through overconfidence in technology, complacence, and a mindset of profits over people’s safety. The tragedy also reveals much about the society and class structure of the time. While the formal findings did not conclude that third class passengers were the victims of intentional discrimination, the statistics of the disaster, where more people in third class died than in any other, tell a more sobering story. In some cases, entire families — mothers, fathers, and children — in third class, perished.

Most of all, the Titanic and the questions it raises reminds us that history isn’t about learning names, events, and dates. Knowing that the Titanic sank at 2:20 a.m. on April 15, 1912, doesn’t begin to convey what happened that night and why, more than a century later, we’re still drawn to this event.

We can never really know what it was like to be there when 1,496 men, women, and children perished in the icy black waters of the Atlantic.

But through the voices of survivors, we can begin to imagine how desperately Marconi operator Jack Phillips worked in those final hours, feel Charlotte Collyer’s pain as she said good-bye to her beloved husband, and picture the despair on Thomas Andrews’s face the moment he saw water pouring in and realized that this incredible ship — and so many on board her — was doomed.