After college graduation, I wasn’t sure what to do next. It felt too late in the game to try medicine, but still too early to retire. A career in education seemed appealing, but I couldn’t shake the little voice that kept reminding me how kids could be twerps. Comedy was still a possibility, though a remote one. I didn’t know many professional comedians personally, and the ones I did know were older friends from college who held day jobs as well; the odds of being able to make comedy a full-time profession, to me, seemed low. And so, I decided to put off making any enormous, adult decisions by continuing to go to school. Education is a journey, I told myself. Plus, your parents can probably be persuaded to spring for your tuition and then you won’t need to make any big moves for a year.

And so I spent nine months in England, where I studied British literature at Oxford. My focus was nineteenth-century British fiction, but most of my energy went into the Oxford University Dramatic Society (OUDS) and McVitie’s Digestives. These scrumptious biscuits made me feel healthy because of the word digestive, but really, they are just cookies—and the very best ones have chocolate and caramel on top. Anyway, having all of these new English cookies at my disposal was invigorating—and I enjoyed being involved with OUDS, even starring in the chorus of My Fair Lady at Magdalen College that spring—but I felt impatient to get back home. I knew that I didn’t want to pursue academics at a professional level, and I wasn’t quite sure what I was doing there, besides eating all the McVitie’s.

Then, the following summer, I performed in a children’s play at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival. The play was called The White Slipper, and mostly what I remember is a lot of ribbon work. However, spending three weeks in Edinburgh and seeing a ton of comedy reminded me how much I missed doing improv. I saw Baby Wants Candy, a Chicago improv-musical group, more than a dozen times. I saw Jo Brand’s stand-up act twice. I saw the Flight of the Conchords do their show High on Folk, I caught Demetri Martin in his one-man show If I, and I watched Waen Shepherd perform his character Gary Le Strange. These live performances electrified me: is it too bold to say that I suddenly felt that I, too, might be able to do something like that? Because I did. I guess that sometimes it just takes a year of having no real direction or consistent sunlight for the fiery heart to let its passions be known. As it turned out, my own fiery heart was dying to go for the laughs.

My Quipfire friend Scott had just graduated from college the previous spring, and he also wanted to pursue comedy. Another Quipfire friend, Tommy Dewey, had moved to New York after graduating a couple of years earlier, and proceeded to book commercial work within a year. He then moved to Los Angeles, but his success in New York was encouraging to Scott and me. We didn’t consider going to LA—there were too many other aspiring actors there!—and though we knew Chicago was the capital of improv, it seemed like New York might afford us more opportunities for television and commercial work. Honestly, though, why did we think we knew anything? Scott was twenty-two, I was twenty-three, and neither of us had been on any kind of audition outside of school theatre. But as Quipfire alums and good friends, we shared the vague notion that we would enroll in improv classes in New York and try to put on shows together.

We found an apartment on Eightieth Street across from Zabar’s on the Upper West Side. The next piece of business was to sign up for a Level One improv class at the Upright Citizens Brigade (UCB). This theatre was founded by UCB troupe members Matt Besser, Amy Poehler, Ian Roberts, and Matt Walsh; they had been trained at ImprovOlympic in Chicago, written and starred in their own sketch show on Comedy Central, and opened their first theatre in Manhattan in 2000. To any aspiring New York improviser, this place was a dream. In order to perform on a house team there, a student had to complete all five levels of the curriculum. Feeling like I had no time to waste, I decided to take classes back to back with no break in between. It would still take me a full year to finish. (The only reason I could even consider doing it that way was that I was in the rare position of being able to reach out to my parents for money if I needed it.)

And yet not even Daddy could save me from vermin. A recent perusal of some emails exchanged between Scott, Brian Kerr (our third roommate), and me reveals some harsh truths:

On Wednesday, January 21, 2004 10:21AM, Scott Eckert wrote:

I killed a roach today when it fell out of the dishes cabinet. (Sorry I bent up your old Newsweek, Ellie.) . . .

-Scott

Am I reproducing this email to brag that I used to read Newsweek? A little. But mostly I am showing you that our apartment was gross.

On Friday, 18 June 2004 11:15:58 -0700 (PDT), Ellie Kemper wrote:

i just emptied out the trash from the sink and after i removed the trashbag from the can there were a dozen writhing maggots or mealworms on the bottom. it has repulsed me to the core and i feel ill.

On Friday, June 18, 2004 2:26 PM, Brian Kerr wrote:

what type of food? who leaves meat out? me? eeeeeeeeew

Is this the regular trash bag?

eeeeeeeeeeew

Why does Brian bother to ask what type of food was left out? All types of food! Don’t leave any of it out!

One afternoon I walked into our apartment to find Scott eating a lunch that was completely orange: three slices of cheddar cheese, a handful of carrots, and a large helping of Doritos. Scott looked up at me helplessly from the couch. “What are we doing?”

He was asking the wrong person. My only standing appointment was going to watch Asssscat at UCB every Sunday night. The later show, at 9:30, was free, but sometimes I had trouble staying up that late. So I usually paid the $5 to go see the 7:30 show. Amy Poehler performed most Sundays, and Horatio Sanz did, too. This was certainly the highlight of my week, though I once opened my At-A-Glance weekly calendar and, seeing “Asssscat–7:30” under Sunday as the only event written, began to sob. What is your life, Ellie? I said out loud while also watching myself in the mirror to see how I looked when I cried. What is the plan here?

In retrospect, I see that I did, in fact, have a plan. My younger, weeping self just loved a little melodrama, is all. My plan was to enroll in improv classes at the Peoples Improv Theater (PIT) and UCB. I would perform improv shows with Scott wherever I could. After I had completed my classes, I would audition to be on a house team at both theatres. While I was doing all of that, I would work on my writing. I would submit to free publications and try to figure out how to contribute to The Onion. My sister had interned at Late Night with Conan O’Brien the previous summer, and maybe I would try to get an internship there as well. As a twenty-three-year-old, I loved nothing more than a big fat cry in the pillows, but as someone who is wiser and older now, I see that I did have several concrete goals.

Therefore, despite the maggots and roaches and orange lunches staring me down at every turn, I was able to carry on. Scott and I completed our Level One class at UCB, and we had also started taking an Intro class at the PIT. We were taught to listen to our scene partners and to build scenes as a team. Showboats were discouraged and class clowns frowned upon, which a UCB classmate of mine found out when he decided to squeeze his testicles through his open fly as he entered a scene one afternoon. “Tim,” our teacher said, turning away from his student’s balls. “Don’t do that.”

The reason I fell in love with improv in the first place was the simple concept of listening and responding, so I felt relieved that both theatres embraced this tenet. Moreover, the improv structure at both places was long form. As opposed to the short-form games we had played in college, long-form scenes took what I loved most about improv—truthful reaction in the moment, building on what your scene partner has set forth, creating the scene as an ensemble—and fleshed it out even more. One of my very favorite scenes in college had been during a rare long-form piece; Tommy Dewey played a typewriter-pounding Angela Lansbury witnessing a murder that Scott committed in a cigar lounge. It is precisely this sort of delightfully unexpected turn of events, discovered by performers and audience alike in real time, that makes me adore improv.

After Scott and I completed our Intro level at the PIT, we started performing in a weekly Wednesday night show called “The Mosh,” where any improviser could show up and play. We met a bunch of other improvisers through “The Mosh,” and in the spring of 2004, Scott, Chris Caniglia, Tom Ridgely, Megan Martin, Justin Akin, Dave Lombard, Kristen Schaal, and I formed a team. Against my really strong protests, we named ourselves Big Black Car. I hated this name and I still do. It is the name of a song by Gregory Alan Isakov, which makes it even worse. But though I hated the name of this team, I loved the team itself. We started booking shows in comedy venues around the city—Juvie Hall, Parkside Lounge, Rififi, Under St. Mark’s—and we rehearsed as often as we could. (Many people don’t understand how you can rehearse improvisation, but there are countless forms that improv groups experiment with—my favorite form with Big Black Car was called the Big Black Ballet, which incorporated dance edits into the show—and even though you are making up the show as you go along, the ability to do that requires practice. Also, listening carefully is a skill set just like any other. Hear that, MEN? I’m kidding.1)

Separately, Scott and I started performing two-person improv shows at the PIT that summer. We called our show “At the End of the Day,” and it was a long-form show with no games or rigid structure. We basically did several five-minute scenes, then circled back to revisit the characters established in those scenes; sometimes characters from different scenes met each other, and we always tried to wrap up the stories of these characters as best we could in the final scene. We were also working on a written sketch show so that we would have something to submit to comedy festivals; its working title was “Hope Be Gone.”

Meanwhile, I had completed all five levels of classes at UCB, which meant that I was now eligible to audition for a Harold team. “Harold” was the form of improv that these teams performed at shows; a Harold consists of three chapters of three scenes, punctuated by two group games in between chapters. Auditions were held on a Saturday afternoon in November, and I received an email the next day informing me I had gotten a callback! I was excited but cautious. I called my mom and dad and delivered the good news; they were predictably happy for me, but my mom warned me not to be disappointed if they gave the spot to someone who had been there longer and thus had paid more of her dues. That Monday evening at callbacks, I performed in three two-person scenes and a group game, and I left feeling like I had done my best.

On Tuesday, November 23, I received this email. I was so happy that I didn’t even care about Owen leaving the second “e” off my name!!!

From Owen Burke

11/23/04 at 12:25 PM

Congratulations!

you did it up!

Eric Appel

Elli Kemper

Kristy Kershaw

Rachel Korowitz

Matt Moses

Shannon O’Neill

Gavin Speiller

Dave Thunder

. . . now get together, find a coach and start rehearsing. Your first show is in December.

Contact me for anything.

Total Respect,

Owen

Our team finally decided on the name Mailer Daemon (other contenders were Easy Lover, Brokaw, The Dream Police, and Gigantor), and we began rehearsing right away. By the winter of 2005, I was performing on Tuesdays with Mailer Daemon at UCB and Wednesdays with Big Black Car at the PIT. Scott and I had been given the 9:30 p.m. Saturday slot at the PIT for “At the End of the Day.” I was getting so good at improv it almost wasn’t funny. Is this how Elaine May feels? I asked myself on more than one occasion, referring to one of the greatest improvisers of all time. No, a voice called back to me. She is a genius, a living legend. You do not feel how Elaine May feels.

Being a member of these teams and performing in these shows felt like measurable progress. Now when my parents’ friends asked me what projects I was working on, I could say that I was an improviser at two theatres with weekly shows in Manhattan. Ha! Furthermore, my friend Ptolemy Slocum had told his commercial agent Maura Maloney to come see one of Big Black Car’s shows that winter. She enjoyed the show and invited me to come to her agency, CESD, to meet with some of the other agents there. I signed with their commercial agency the following week and booked two commercials the week after that: one for DSW (Designer Shoe Warehouse) and one for Aquafina. Suddenly I was a working actor!

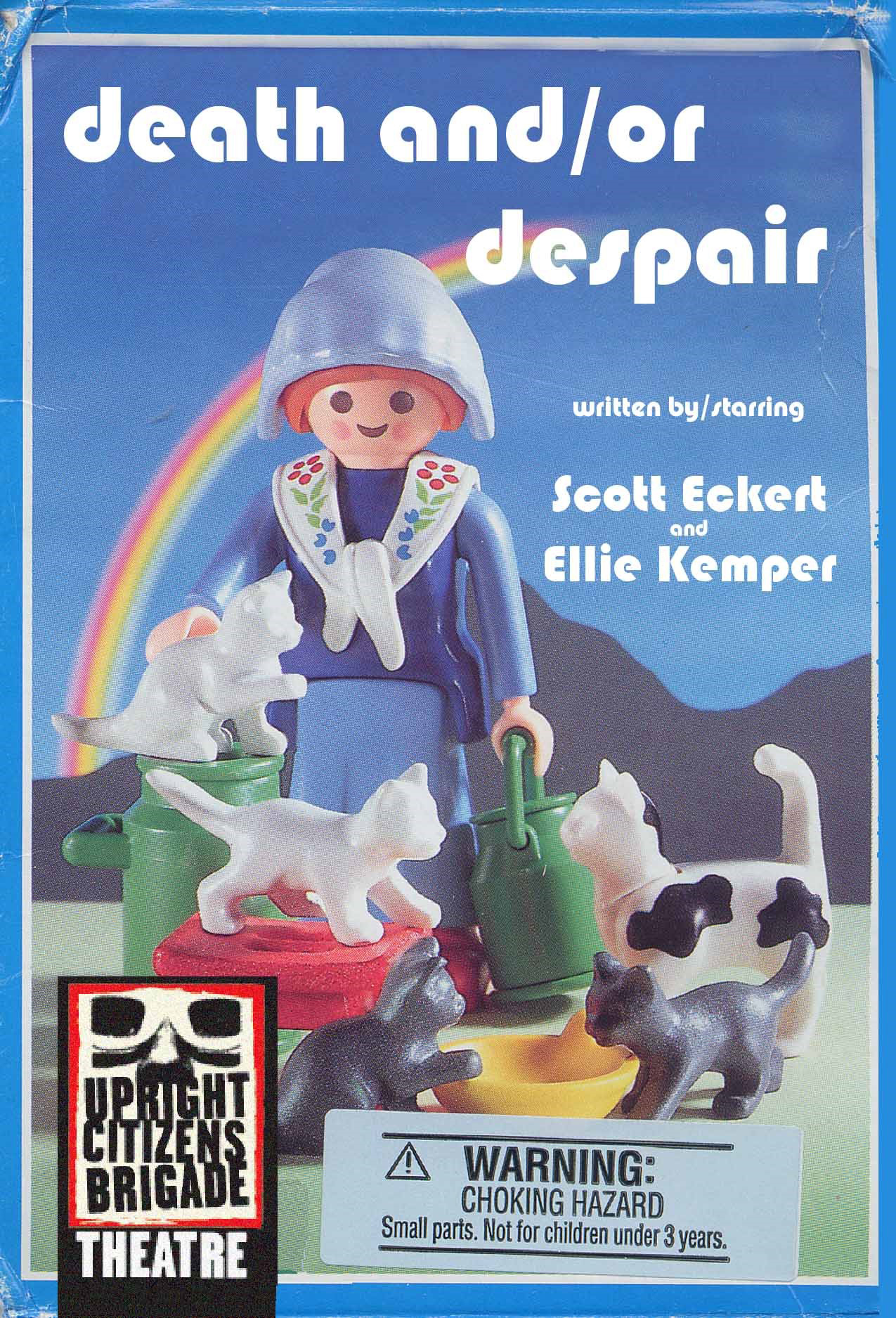

Scott and I finished writing “Hope Be Gone” in the summer of 2005, and we submitted it to UCB. We wanted to get a run at the theatre to bring in theatrical agents, producers, and other executives in showbiz. Anthony King, who was the artistic director at UCB at that time, liked our show but had some ideas for where it could be improved. He also suggested changing the title of our show, and we all agreed that “Death and/or Despair” would be the winner. After implementing Anthony’s notes and working with our friend Jen Nails as well, we received a run at the UCB in October of 2005. Here was our postcard:

The show was all about sadness. It consisted of six segments, including a 1930s-style newsroom romance and a wordless portrait of a heartbroken woman set to Natalie Merchant’s “My Skin.” But what really captured the essence of our show was its opening dance, set to the Disney World soundtrack “Epcot Illusions”:

Lights up on Ellie, alone reading a magazine. Sound of footsteps approaching, faster and faster. Scott appears from backstage. Intense chase sequence ensues. Audience follows as Scott chases Ellie down a fireman’s pole, riding stallions, digging holes, snorkeling under water, dueling with swords, grocery cart shopping, and an ultimate, decisive game of chess. Ellie wins. Scott slashes Ellie’s throat. Ellie falls to ground, dead. Scott licks bloody knife in victory.

Scott and I received a run of our show at the UCB for November and December 2005. Anthony had also submitted our show to the HBO Aspen Comedy Festival. We were ecstatic because this festival was the place for aspiring comedians to make their mark. We did not receive a callback, so our ecstasy quickly gave way to agony. But then our agony gave way to excitement because we still had a two-month run at UCB, and we were packing the house!

On the job side of things, I was lucky to be enjoying a steady string of commercial work. Though my DSW and Aquafina ads only aired locally, I booked a bunch of jobs—Kmart, Wendy’s, M&Ms, Cingular, Citibank—that went national. This was great, because an actor is paid based on the number of times the spot airs, and making money through commercials allowed me greater independence and more time to work on writing and putting up shows. While I continued to perform with Big Black Car and my Harold team (which had undergone a reshuffle in the meantime, losing some members and adding others—we were now called “fwand”), I also started writing more. I began contributing to McSweeney’s regularly (my first piece, “Listen, Kid, The Biggest Thing You’ve Got Going for You Is Your Rack,” had been accepted in December 2005), and I finally was invited to contribute headlines to The Onion around the same time. I had persistently badgered Joe Garden, the features editor, for a solid year—me sending him headline after headline, him suggesting improvement after improvement—until finally he added me to the group of contributing writers. I did not know Joe Garden previously or have any connection to him; I saw his name on the masthead and mailed a hard copy letter to The Onion office addressed to him. I had picked him because he was listed first alphabetically. Luckily, I happened to pick one of the friendliest and most generous people I have ever had the pleasure of knowing.

I also started working on a one-person show. I called this show Dumb Girls, and it was a character showcase of ladies who weren’t too bright. I put it up at UCB in the fall of 2006, and it got some good attention, but nothing Earth-shattering.

I went back to work on a different one-person show that I would eventually call Feeling Sad/Mad with Ellie Kemper. This was a show about ladies whose lives were falling apart. Writing this show felt like torture, because I wasn’t sure what I was trying to do. Everything that I came up with felt clichéd, and I found that I, too, was beginning to feel pretty sad and mad myself! Thankfully, I enlisted the help of Jason Mantzoukas, a friend from UCB, and he whipped the show into shape. We created a manic airline attendant “host,” who would serve as the through line. We gradually developed five other crazy ladies, and the premise of the show was that these ladies were all waiting at various spots in the airport for their Alaska Airlines Flight #404 to board. And then the airplane crashes before it even gets to the airport. It took a lot of performances to get this show right. One night, I performed to a mostly full house and—no exaggeration—there was one laugh. I wanted to die. In fact, walking to the subway after that show, I vowed to quit comedy. By the time I emerged from the subway, however, I had decided to rejoin comedy. I went into my apartment, put on a DVD of The Tracey Ullman Show, realized that I would never be as talented as Tracey Ullman, but that I would still like to be a performer.

That brief surge of adrenaline that I’d felt when improvising in Christmas Magic so many years ago had managed to carry me through the next decade and a half. The truth is, I enjoyed the exhilaration and the thrill of not knowing what was coming next. I am also a fairly obedient person in real life, so it’s therapeutic to play women who are slightly unhinged on stage.

I received a run of Sad/Mad at UCB in the summer of 2008, and in August, I was invited to perform in a showcase for Saturday Night Live (more on this juicy nugget later). The SNL audition brought me to the attention of other showrunners and agents. And that is why I was able to get a meeting with Greg Daniels and Mike Schur from The Office in the fall of 2008. But none of that would have taken place if I had not written a show for myself, created characters to perform, and made a product to share with the industry.

Also: luck. So much of show business comes down to good luck. And if you have it, be sure to sprinkle it on others. That’s what she said? Keep reading . . .

1 Not kidding at all. Men, try to listen better!