Chapter 1

Belshazzar’s Decision

“Bel, come here!” The Harvester sat in the hollow worn in the hewed log stoop by the feet of his father and mother and his own sturdier tread, and rested his head against the casing of the cabin door when he gave the command. The tip of the dog’s nose touched the gravel between his paws as he crouched flat on earth, with beautiful eyes steadily watching the master, but he did not move a muscle.

“Bel, come here!”

Twinkles flashed in the eyes of the man when he repeated the order, while his voice grew more imperative as he stretched a lean, wiry hand toward the dog. The animal’s eyes gleamed and his sensitive nose quivered, yet he lay quietly.

“Belshazzar, kommen Sie hier!”

The body of the dog arose on straightened legs and his muzzle dropped in the outstretched palm. A wind slightly perfumed with the odour of melting snow and unsheathing buds swept the lake beside them, and lifted a waving tangle of light hair on the brow of the man, while a level ray of the setting sun flashed across the water and illumined the graven, sensitive face, now alive with keen interest in the game being played.

“Bel, dost remember the day?” inquired the Harvester.

The eager attitude and anxious eyes of the dog betrayed that he did not, but was waiting with every sense alert for a familiar word that would tell him what was expected.

“Surely you heard the killdeers crying in the night,” prompted the man. “I called your attention when the ecstasy of the first bluebird waked the dawn. All day you have seen the gold-yellow and blood-red osiers, the sap-wet maples and spring tracing announcements of her arrival on the sunny side of the levee.”

The dog found no clew, but he recognized tones he loved in the suave, easy voice, and his tail beat his sides in vigorous approval. The man nodded gravely.

“Ah, so! Then you realize this day to be the most important of all the coming year to me; this hour a solemn one that influences my whole after life. It is time for your annual decision on my fate for a twelve-month. Are you sure you are fully alive to the gravity of the situation, Bel?”

The dog felt himself safe in answering a rising inflection ending in his name uttered in that tone, and wagged eager assent.

“Well then,” said the man, “which shall it be? Do I leave home for the noise and grime of the city, open an office and enter the money-making scramble?”

Every word was strange to the dog, almost breathlessly waiting for a familiar syllable. The man gazed steadily into the animal’s eyes. After a long pause he continued:

“Or do I remain at home to harvest the golden seal, mullein, and ginseng, not to mention an occasional hour with the black bass or tramps for partridge and cotton-tails?”

The dog recognized each word of that. Before the voice ceased, his sleek sides were quivering, his nostrils twitching, his tail lashing, and at the pause he leaped up and thrust his nose against the face of the man. The Harvester leaned back laughing in deep, full-chested tones; then he patted the dog’s head with one hand and renewed his grip with the other.

“Good old Bel!” he cried exultantly. “Six years you have decided for me, and right—every time! We are of the woods, Bel, born and reared here as our fathers before us. What would we of the camp fire, the long trail, the earthy search, we harvesters of herbs the famous chemists require, what would we do in a city? And when the sap is rising, the bass splashing, and the wild geese honking in the night! We never could endure it, Bel.

“When we delivered that hemlock at the hospital to-day, did you hear that young doctor talking about his ‘lid’? Well up there is ours, old fellow! Just sky and clouds overhead for us, forest wind in our faces, wild perfume in our nostrils, muck on our feet, that’s the life for us. Our blood was tainted to begin with, and we’ve lived here so long it is now a passion in our hearts. If ever you sentence us to life in the city, you’ll finish both of us, that’s what you’ll do! But you won’t, will you? You realize what God made us for and what He made for us, don’t you, Bel?”

As he lovingly patted the dog’s head the man talked and the animal trembled with delight. Then the voice of the Harvester changed and dropped to tones of gravest import.

“Now how about that other matter, Bel? You always decide that too. The time has come again. Steady now! This is far more important than the other. Just to be wiped out, Bel, pouf! That isn’t anything and it concerns no one save ourselves. But to bring misery into our lives and live with it daily, that would be a condition to rend the soul. So careful, Bel! Cautious now!”

The voice of the man dropped to a whisper as he asked the question.

“What about the girl business?”

Trembling with eagerness to do the thing that would bring more caressing, bewildered by unfamiliar words and tones, the dog hesitated.

“Do I go on as I have ever since mother left me, rustling for grub, living in untrammelled freedom? Do I go on as before, Bel?”

The Harvester paused and waited the answer, with anxiety in his eyes as he searched the beast face. He had talked to that dog, as most men commune with their souls, for so long and played the game in such intense earnest that he felt the results final with him. The animal was immovable now, lost again, his anxious eyes watching the face of the master, his eager ears waiting for words he recognized. After a long time the man continued slowly and hesitantly, as if fearing the outcome. He did not realize that there was sufficient anxiety in his voice to change its tones.

“Or do I go courting this year? Do I rig up in uncomfortable store-clothes, and parade before the country and city girls and try to persuade the one I can get, probably—not the one I would want—to marry me, and come here and spoil all our good times? Do we want a woman around scolding if we are away from home, whining because she is lonesome, fretting for luxuries we cannot afford to give her? Are you going to let us in for a scrape like that, Bel?”

The bewildered dog could bear the unusual scene no longer. Taking the rising inflection, that sounded more familiar, for a cue, and his name for a certainty, he sprang forward, his tail waving as his nose touched the face of the Harvester. Then he shot across the driveway and lay in the spice thicket, half the ribs of one side aching, as he howled from the lowest depths of dog misery.

“You ungrateful cur!” cried the Harvester. “What has come over you? Six years I have trusted you, and the answer has been right, every time! Confound your picture! Sentence me to tackle the girl proposition! I see myself! Do you know what it would mean? For the first thing you’d be chained, while I pranced over the country like a half-broken colt, trying to attract some girl. I’d have to waste time I need for my work and spend money that draws good interest while we sleep, to tempt her with presents. I’d have to rebuild the cabin and there’s not a chance in ten she would not fret the life out of me whining to go to the city to live, arrange for her here the best I could. Of all the fool, unreliable dogs that ever trod a man’s tracks, you are the limit! And you never before failed me! You blame, degenerate pup, you!”

The Harvester paused for breath and the dog subsided to a pitiful whimper. He was eager to return to the man who had struck him the first blow his pampered body ever had received; but he could not understand a kick and harsh words for him, so he lay quivering with anxiety and fear.

“You howling, whimpering idiot!” exclaimed the Harvester. “Choose a day like this to spoil! Air to intoxicate a mummy! Roots swelling! Buds bursting! Harvest close and you’d call me off and put me at work like that, would you? If I ever had supposed lost all your senses, I never would have asked you. Six years you have decided my fate, when the first bluebird came, and you’ve been true blue every time. If I ever trust you again! But the mischief is done now.

“Have you forgotten that your name means ‘to protect’? Don’t you remember it is because of that, it is your name? Protect! I’d have trusted you with my life, Bell! You gave it to me the time you pointed that rattler within six inches of my fingers in the blood-root bed. You saw the falling limb in time to warn me. You always know where the quicksands lie. But you are protecting me now, like sin, ain’t you? Bring a girl here to spoil both our lives! Not if I know myself! Protect!”

The man arose and going inside the cabin closed the door. After that the dog lay in abject misery so deep that two big tears squeezed from his eyes and rolled down his face. To be shut out was worse than the blow. He did not take the trouble to arise from the wet leaves covering the cold earth, but closing his eyes went to sleep.

The man leaned against the door and ran his fingers through his hair as he anathematized the dog. Slowly his eyes travelled around the room. He saw his tumbled bed by the open window facing the lake, the small table with his writing material, the crude rack on the wall loaded with medical works, botanies, drug encyclopaedias, the books of the few authors who interested him, and the bare, muck-tracked floor. He went to the kitchen, where he built a fire in the cook stove, and to the smoke-house, from which he returned with a slice of ham and some eggs. He set some potatoes boiling and took bread, butter and milk from the pantry. Then he laid a small note-book on the table before him and studied the transactions of the day.

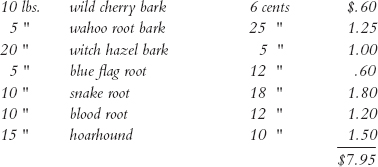

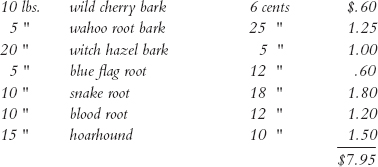

“Not so bad,” he muttered, bending over the figures. “I wonder if any of my neighbours who harvest the fields average as well at this season. I’ll wager they don’t. That’s pretty fair! Some days I don’t make it, and then when a consignment of seeds go or ginseng is wanted the cash comes in right properly. I could waste half of it on a girl and yet save money. But where is the woman who would be content with half? She’d want all and fret because there wasn’t more. Blame that dog!”

He put the book in his pocket, prepared and ate his supper, heaped a plate generously, placed it on the floor beneath the table, and set away the food that remained.

“Not that you deserve it,” he said to space. “You get this in honour of your distinguished name and the faithfulness with which you formerly have lived up to its import. If you hadn’t been a dog with more sense than some men, I wouldn’t take your going back on me now so hard. One would think an animal of your intelligence might realize that you would get as much of a dose as I. Would she permit you to eat from a plate on the kitchen floor? Not on your life, Belshazzar! Frozen scraps around the door for you! Would she allow you to sleep across the foot of the bed? Ho, ho, ho! Would she have you tracking on her floor? It would be the barn, and growling you didn’t do at that. If I’d serve you right, I’d give you a dose and allow you to see how you like it. But it’s cutting off my nose to spite my face, as the old adage goes, for whatever she did to a dog, she’d probably do worse to a man. I think not!”

He entered the front room and stood before a long shelf on which were arranged an array of partially completed candlesticks carved from wood. There were black and white walnut, red, white, and golden oak, cherry and curly maple, all in original designs. Some of them were oddities, others were failures, but most of them were unusually successful. He selected one of black walnut, carved until the outline of his pattern was barely distinguishable. He was imitating the trunk of a tree with the bark on, the spreading, fern-covered roots widening for the base, from which a vine sprang. Near the top was the crude outline of a big night moth climbing toward the light. He stood turning this stick with loving hands and holding it from him for inspection.

“I am going to master you!” he exulted. “Your lines are right. The design balances and it’s graceful. If I have any trouble it will be with the moth, and I think I can manage. I’ve got to decide whether to use cecropia or polyphemus before long. Really, on a walnut, and in the woods, it should be a luna, according to the eternal fitness of things—but I’m afraid of the trailers. They turn over and half curl and I believe I had better not tackle them for a start. I’ll use the easiest to begin on, and if I succeed I’ll duplicate the pattern and try a luna then. The beauties!”

The Harvester selected a knife from the box and began carving the stick slowly and carefully. His brain was busy, for presently he glanced at the floor.

“She’d object to that!” he said emphatically. “A man could no more sit and work where he pleased than he could fly. At least I know mother never would have it, and she was no nagger, either. What a mother she was! If one only could stop the lonely feeling that will creep in, and the aching hunger born with the body, for a mate; if a fellow only could stop it with a woman like mother! How she revelled in sunshine and beauty! How she loved earth and air! How she went straight to the marrow of the finest line in the best book I could bring from the library! How clean and true she was and how unyielding! I can hear her now, holding me with her last breath to my promise. If I could marry a girl like mother—great Caesar! You’d see me buying an automobile to make the run to the county clerk. Wouldn’t that be great! Think of coming in from a long, difficult day, to find a hot supper, and a girl such as she must have been, waiting for me! Bel, if I thought there was a woman similar to her in all the world, and I had even the ghost of a chance to win her, I’d call you in and forgive you. But I know the girls of to-day. I pass them on the roads, on the streets, see them in the cafe’s, stores, and at the library. Why even the nurses at the hospital, for all the gravity of their positions, are a giggling, silly lot; and they never know that the only time they look and act presentably to me is when they stop their chatter, put on their uniforms, and go to work. Some of them are pretty, then. There’s a little blue-eyed one, but all she needs is feathers to make her a ‘ha! ha! bird.’ Drat that dog!”

The Harvester took the candlestick and the box of knives, opened the door, and returned to the stoop. Belshazzar arose, pleading in his eyes, and cautiously advanced a few steps. The man bent over his work and paid not the slightest heed, so the discouraged dog sank to earth and fixedly watched the unresponsive master. The carving of the candlestick went on steadily. Occasionally the Harvester lifted his head and repeatedly sucked his lungs full of air. Sometimes for an instant he scanned the surface of the lake for signs of breaking fish or splash of migrant water bird. Again his gaze wandered up the steep hill, crowned with giant trees, whose swelling buds he could see and smell. Straight before him lay a low marsh, through which the little creek that gurgled and tumbled down hill curved, crossed the drive some distance below, and entered the lake of Lost Loons.

While the trees were bare, and when the air was clear as now, he could see the spires of Onabasha, five miles away, intervening cultivated fields, stretches of wood, the long black line of the railway, and the swampy bottom lands gradually rising to the culmination of the tree-crowned summit above him. His cocks were crowing warlike challenges to rivals on neighbouring farms. His hens were carolling their spring egg-song. In the barn yard ganders were screaming stridently. Over the lake and the cabin, with clapping snowy wings, his white doves circled in a last joy-flight before seeking their cotes in the stable loft. As the light grew fainter, the Harvester worked slower. Often he leaned against the casing, and closed his eyes to rest them. Sometimes he whistled snatches of old songs to which his mother had cradled him, and again bits of opera and popular music he had heard on the streets of Onabasha. As he worked, the sun went down and a half moon appeared above the wood across the lake. Once it seemed as if it were a silver bowl set on the branch of a giant oak; higher, it rested a tilted crescent on the rim of a cloud.

The dog waited until he could endure it no longer, and straightening from his crouching position, he took a few velvet steps forward, making faint, whining sounds in his throat. When the man neither turned his head nor gave him a glance, Belshazzar sank to earth again, satisfied for the moment with being a little closer. Across Loon Lake came the wavering voice of a night love song. The Harvester remembered that as a boy he had shrunk from those notes until his mother explained that they were made by a little brown owl asking for a mate to come and live in his hollow tree. Now he rather liked the sound. It was eloquent of earnest pleading. With the lonely bird on one side, and the reproachful dog eyes on the other, the man grinned rather foolishly.

Between two fires, he thought. If that dog ever catches my eye he will come tearing as a cyclone, and I would not kick him again for a hundred dollars. First time I ever struck him, and didn’t intend to then. So blame mad and disappointed my foot just shot out before I knew it. There he lies half dead to make up, but I’m blest if I forgive him in a hurry. And there is that insane little owl screeching for a mate. If I’d start out making sounds like that, all the girls would line up and compete for possession of my happy home.

The Harvester laughed and at the sound Belshazzar took courage and advanced five steps before he sank belly to earth again. The owl continued its song. The Harvester imitated the cry and at once it responded. He called again and leaned back waiting. The notes came closer. The Harvester cried once more and peered across the lake, watching for the shadow of silent wings. The moon was high above the trees now, the knife dropped in the box, the long fingers closed around the stick, the head rested against the casing, and the man intoned the cry with all his skill, and then watched and waited. He had been straining his eyes over the carving until they were tired, and when he watched for the bird the moonlight tried them; for it touched the lightly rippling waves of the lake in a line of yellow light that stretched straight across the water from the opposite bank, directly to the gravel bed below, where lay the bathing pool. It made a path of gold that wavered and shimmered as the water moved gently, but it appeared sufficiently material to resemble a bridge spanning the lake.

“Seems as if I could walk it,” muttered the Harvester.

The owl cried again and the man intently watched the opposite bank. He could not see the bird, but in the deep wood where he thought it might be he began to discern a misty, moving shimmer of white. Marvelling, he watched closer. So slowly he could not detect motion it advanced, rising in height and taking shape.

“Do I end this day by seeing a ghost?” he queried.

He gazed intently and saw that a white figure really moved in the woods of the opposite bank.

“Must be some boys playing fool pranks!” exclaimed the Harvester.

He watched fixedly with interested face, and then amazement wiped out all other expression and he sat motionless, breathless, looking, intently looking. For the white object came straight toward the water and at the very edge unhesitatingly stepped upon the bridge of gold and lightly, easily advanced in his direction. The man waited. On came the figure and as it drew closer he could see that it was a very tall, extremely slender woman, wrapped in soft robes of white. She stepped along the slender line of the gold bridge with grace unequalled.

From the water arose a shining mist, and behind the advancing figure a wall of light outlined and rimmed her in a setting of gold. As she neared the shore the Harvester’s blood began to race in his veins and his lips parted in wonder. First she was like a slender birch trunk, then she resembled a wild lily, and soon she was close enough to prove that she was young and very lovely. Heavy braids of dark hair rested on her head as a coronet. Her forehead was low and white. Her eyes were wide-open wells of darkness, her rounded cheeks faintly pink, and her red lips smiling invitation. Her throat was long, very white, and the hands that caught up the fleecy robe around her were rose-coloured and slender. In a panic the Harvester saw that the trailing robe swept the undulant gold water, but was not wet; the feet that alternately showed as she advanced were not purple with cold, but warm with a pink glow.

She was coming straight toward him, wonderful, alluring, lovely beyond any woman the Harvester ever had seen. Straightway the fountains of twenty-six years’ repression overflowed in the breast of the man and all his being ran toward her in a wave of desire. On she came, and now her tender feet were on the white gravel. When he could see clearly she was even more beautiful than she had appeared at a distance. He opened his lips, but no sound came. He struggled to rise, but his legs would not bear his weight. Helpless, he sank against the casing. The girl walked to his feet, bent, placed a hand on each of his shoulders, and smiled into his eyes. He could scent the flower-like odour of her body and wrapping, even her hair. He struggled frantically to speak to her as she leaned closer, yet closer, and softly but firmly laid lips of pulsing sweetness on his in a deliberate kiss.

The Harvester was on his feet now. Belshazzar shrank into the shadows.

“Come back!” cried the man. “Come back! For the love of mercy, where are you?”

He ran stumblingly toward the lake. The bridge of gold was there, the little owl cried lonesomely; and did he see or did he only dream he saw a mist of white vanishing in the opposite wood?

His breath came between dry lips, and he circled the cabin searching eagerly, but he could find nothing, hear nothing, save the dog at his heels. He hurried to the stoop and stood gazing at the molten path of moonlight. One minute he was half frozen, the next a rosy glow enfolded him. Slowly he lifted a hand and touched his lips. Then he raised his eyes from the water and swept the sky in a penetrant gaze.

“My gracious Heavenly Father,” said the Harvester reverently. “Would it be like that?”