1. BRAM STOKER AND VALDIMAR ÁSMUNDSSON

FOR MORE THAN A CENTURY, THE LANGUAGE BARRIER between Iceland and the rest of the world has prevented readers from enjoying the unique work presented here—an early and significant variation on Bram Stoker’s world famous Dracula, rather more than just a translation into Icelandic by one of the country’s foremost literary talents, Valdimar Ásmundsson. Partly due to the rarity of the book, it has remained hidden to even the most versed scholars. Valdimar’s1 life and work are virtually unknown outside of Iceland. And even in his home country, no one ever studied how Stoker’s vampire story, only a few years after its first publication, made its way to the Far North.

Jóhann Valdimar Ásmundsson was born in 1852 and grew up with his parents in Þistilfjörður2—a remote bay in the very northeast of Iceland. He was largely self-educated and taught himself English, German and French, aside from Norwegian, Swedish, Danish, and some Latin and Greek. Bram Stoker, by contrast, had the privilege of studying at Trinity College in Dublin from 1864-1870, but after receiving a B.A. with honors in mathematics, he had to enter work life as a civil servant at Dublin Castle, where his father worked as well: three of Bram’s brothers studied at the Royal College of Surgeons, and Bram’s income was needed to support the family. Despite these different backgrounds, both Valdimar and Bram started out as journalists in the 1870s. Valdimar wrote his first articles for Norðanfara, a newspaper in Akureyri in the north of Iceland, published by Björn Jónsson, who would become publisher/editor of Ísafold,3 while Bram volunteered to write theatre reviews for the Dublin Evening Mail, co-owned by Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu, the author of Carmilla. After writing a rapturous review of Henry Irving’s performance as Hamlet at the Theatre Royal in Dublin in 1876, Bram met with the actor—a meeting that would change his life and career. In 1878 Irving invited him to come to London and become the manager of the Lyceum Theatre, which the actor intended to lease. Some years later, Valdimar also moved south: in winter 1882 he became a teacher at Flensborg School in Hafnarfjörður—one of the oldest schools in Iceland still in existence today.4 During these early years he created a very popular and widely used grammar book, Ritreglur, just like Stoker, during his years at Dublin Castle, had written The Duties of Clerks of Petty Sessions in Ireland (1879), a detailed professional handbook that also would become a standard in its field. And just like Bram, Valdimar finally moved to the “big city,” to Reykjavík—although London had quite different dimensions than the Icelandic capital.

In the 1880s, London, the political and cultural center of the global British Empire, already had a population of 4 million, with another million inhabiting its outskirts. Reykjavík, by contrast, had only 3,000 to 4,000 residents; its center was tiny, with only one main street, so that the paths of the local officials, teachers and other intellectuals must have crossed every other day. But just like Bram Stoker started meeting people of the highest London circles, who came to admire the Shakespeare plays revived by Irving, the most celebrated actor of his time, so Valdimar set up shop in the local center of power. In February 1884, he founded the newspaper Fjallkonan (“Lady of the Mountains”), referring to a mythical figure symbolizing the Icelandic nation.5 Fjallkonan focused on political and cultural news, summarized the foreign press, reviewed books and published obituaries, boat schedules, and advertisements. It became one of Iceland’s leading newspapers, with around 2,000 subscribers. It positioned itself as the champion of farmers and traders, supporting Iceland’s independence, free trade, better education, and technical progress.6

Center of Reykjavík in 1915 (detail)—map by Ólafur Thorsteinsson. Black star: Old office of Fjallkonan at Veltusund 3. White star: Thingholtsstræti 18. Nr. 1: Government House. Nr. 2: Dómkirkja. Nr. 3: Latin School. Nr. 4: Alþingishús + National Library 1881-1908. Nr. 5: Reykjavík Pharmacy. Nr. 6: Good Templar House (promoting abstinence from alcohol and cursing). Nr. 7: Police Office. Nr. 8: Iðnó Theatre, built in 1897. Nr. 9: Children’s School, after 1898 (formerly in Posthússtræti). Nr. 10: K.F.U.M. = Kristilegt félag ungra manna = Y.M.C.A. Nr. 11: Gutenbergprentsmiðja. Nr. 12: Félagsprentsmiðja (where Fjallkonan was printed in the 1890’s). Nr. 13: Nathan & Ólsen (store). Nr. 14: Post Office. Nr. 15: Ísafoldarprentsmiðja. Nr. 16: Albert Thorvaldsen Statue. Nr. 17: Hotel Reykjavík (burnt down in April 1915). Nr. 18: Sáfnahús (National Library and Museum, after 1908). Nr. 19: National Bank, rebuilt after the fire of 1915. Nr. 20: Gamla Bíó (cinema, 1906-1925, before moving to Ingólfsstræti 2a). Nr. 21: Bárubúð or Báruhús: Meeting House.

In 1888, Valdimar married Bríet Bjarnhéðinsdóttir, one of Iceland’s first women’s rights activists and founder of Kvennablaðið, the first Icelandic women’s magazine. Internationally, voting rights and public education for women were among the most controversial political issues of the day; in Dublin, Bram’s mother Charlotte had been fighting for the same goals.

In November 1890, Valdimar and Bríet bought a two-story stone house at Thingholtsstræti no. 18, somewhat farther away from the new House of Parliament (built 1881-82) but nearer to several printing companies. While Bram had his workplace in the London Strand and lived in the fashionable Chelsea area, Valdimar and Bríet were now settled in the “Fleet Street of Reykjavík.”7 Business was not the only reason for the relocation, though: in 1890, their daughter Laufey was born, followed by her little brother Héðinn in 1892. Bram Stoker and Florence Balcombe, who had married already in 1878 before moving to London, only had one child, Noel, born on the last day of 1879. Noel would be boarded at Summer Fields School and later at Winchester College in Oxford, while Laufey and Héðinn remained with their parents and attended the Children’s School, later the Latin School, just a few footsteps from their home.

Although both Valdimar and Bram successfully climbed the social ladder, the men also had a certain modesty in common. In a letter to the American poet Walt Whitman, Bram wrote: “I am equal in temper and cool in disposition and have a large amount of self-control and am naturally secretive to the world.”8 Irving’s stage partner Ellen Terry noted that in the voluminous Reminiscences of Henry Irving, Bram Stoker “described every one connected with the Lyceum except himself.”9 And some of Stoker’s biographers remarked that the author of Dracula seemed to be overshadowed by his own creation.10 Similarly, Valdimar is often only remembered as the husband of Bríet, or as the editor of Fjallkonan at the most; his private life remained in the background. In his obituary, Valdimar’s intimate friend Jón Ólafsson wrote:

He was a very reticent and reserved man, and sometimes almost seemed shy. And many who only knew him superficially thought that he was no emotional person, because he showed only little of his feelings. But those who were closer to him knew that this shy and distanced man was most entertaining in the small circle of his friends, cheery, playful and funny, and that his cool appearance as a closed individual was just a mask concealing a warm and sensitive heart—sensitive to all kinds of suffering, sensitive in his friendships, but above all things sensitive against all injustice and oppression and baseness.11

Valdimar Ásmundsson, Briét Bjarnhéðinsdóttir and their children Laufey (l) and Héðinn (r), around 1900

Ólafsson also stressed that Valdimar had acquired all his knowledge on his own, from a true desire to learn and understand. According to Ásgeir Jónsson, to a certain extent he always remained “the farmer boy from the North,” a “self-made man,”12 and did not seamlessly fit in with the Icelandic scholars of his time. Still, Valdimar became a recognized specialist for old Icelandic manuscripts, and in their obituaries of him, Jón Ólafsson and Bríet agree that he was believed to have no peers among his contemporaries. For the publisher Sigurður Kristjánsson he prepared an illustrated edition of Icelandic sagas in 38 volumes;13 these low-priced books secured a still wider spread of these old tales and eliminated the need to copy them by hand, as had been the tradition for centuries. Moreover, Valdimar became an expert for property border issues for lands that had been settled hundreds of years earlier. Because many of these official rulings had sunk into oblivion, Valdimar’s knowledge of old manuscripts was crucial in reconstructing the earlier decisions from ancient documents.14 From 1887 on, he also received a modest grant from the Icelandic Parliament to reorganize the government archives. Finally, he was a Trustee of the Icelandic Archeological Society (Hið íslenzka fornleifafélag, founded 1879) and edited its yearbook in the 1890s, and co-founded the Icelandic Association of Journalists (Blaðamannafélag) in November 1897, together with Bríet, Björn Jónsson, Jón Ólafsson and others.

Although his tasks in the Society and the Association probably were unpaid, the other activities brought him some extra income, just as trading with old books did later.15 In 1895, he explained to his readers that producing a weekly newspaper with costs of 60-70 Crowns16 per issue—fees for writing and editing, not included—plus around 600 Crowns yearly for postage, was certainly not making him and his family rich, especially as the income from advertisements was lower than it was for comparable newspapers in the UK.17 The price for the house had been 7,000 Crowns and, starting on 14 May 1901, ten yearly mortgage payments of 320 Crowns were due to the previous owner, Arnbjörn Ólafsson. After that, there still were the old debts on the house that Valdimar had taken over.18

On the other side of the Atlantic, Bram Stoker’s financial situation was not very rosy either. Although he had an extremely busy job as Irving’s manager, in 1890 he entered a partnership in The International Library, an imprint of Heinemann & Balestier Ltd. The enterprise failed; Stoker lost his invested capital. His investment in 20 shares of Paige Compositor Manufacturing Co., a technology to which his friend Mark Twain had bought all rights,19 also turned out to be a financial disaster. In June 1896, Bram was forced to borrow £600 from his best friend, Hall Caine, and was only able to pay him back by signing over a life insurance policy.20 Some time later, the golden times of the Lyceum Theatre seemed to come to an end. In December 1896 Irving badly hurt his knee and could not perform for ten weeks; this killed the winter season. In February 1898, the Lyceum storage at Bear Lane in Southwark burned out; the fire destroyed countless stage sets and props that were needed for the theatre’s regular productions. “But the tide must turn some time—otherwise the force would be not a tide but a current,” Stoker noted in his Reminiscences of Henry Irving some years later.21 In 1899, Irving fell ill with pleurisy, and the same year, he transferred the lease of the theatre to a consortium headed by Joseph Comyns Carr—without consulting Stoker. By this time, Irving’s manager hoped that a literary career might offer a financial safety net.

Earning money with novels seemed not at all unrealistic at that time. Stoker’s American friend Twain had made a fortune with writing, before he lost everything with the Paige bankruptcy in 1894 and had to start all over again.22Through an international lecture tour about his work, Twain was able to generate fresh income and pay off all his debts by 1898. Hall Caine was also successful, especially with The Bondman, a novel set in Iceland, which Stoker had managed to bring to Heinemann as its first publishing project in 1890.

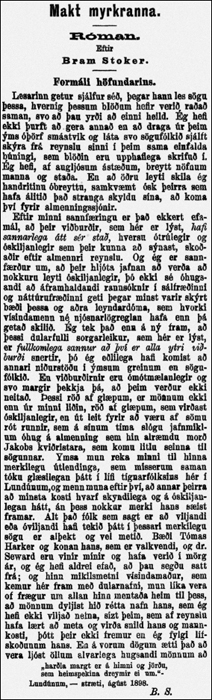

Preface to Makt Myrkranna in the first installment in Fjallkonan, 13 January 1900

2. DRACULA AND MAKT MYRKRANNA

From 1890 on, Bram Stoker worked on Dracula and when the book was finally published on 26 May 1897, it was well received by the international press.23 While Stoker prepared an American edition (1899), then an abridged edition (1901) of his novel, in Reykjavík Valdimar Ásmundsson worked on the Icelandic version, to be serialized in his newspaper Fjallkonan as “Makt Myrkranna, by Bram Stoker.” It was only with the book edition published in August 1901 that the credit “translated by Valdimar Ásmundsson” was added.

Dracula only turned into a real hit after the 1931 movie with Bela Lugosi was released by Universal Pictures. Until then, it generated only a modest income for Bram and his family. After Bram’s death, Florence was confronted with Nosferatu, Werner Murnau’s unauthorized movie version, and bitterly pursued lawsuits against its production company Prana Film until it went bankrupt.

Despite his legal background, Stoker failed to send a copy of his work to the United States Copyright Office in time to have his rights duly registered;24 when Universal started to negotiate with Florence Stoker about a second Dracula movie, Dracula’s Daughter, the material turned out to be unprotected. Dracula fell into the public domain in the U.S. and every script writer, film producer or theatre manager was free to make money with Stoker’s characters—an ironic twist of history, given how little money Stoker himself saw.

But perhaps Stoker’s very mistake helped Dracula reach global fame; the many unauthorized screen adaptations made Stoker’s vampire character known to an ever-growing international public. More than 200 movies featuring the undead Count have by now been produced. Today, the secondary literature about Stoker’s creation is extensive enough to fill a small library. The Icelandic version, by contrast, was reviewed only once in the Icelandic press, in 1906, by Benedikt Björnsson (1879-1941). Björnsson was of a younger generation than Valdimar and feared that the translation of “cheap” sensational fiction from abroad might replace Iceland’s own literary production, including his own:

“Without doubt, for the largest part it is worthless rubbish and sometimes even worse than worthless, completely devoid of poetry and beauty and far removed from any psychological truth.”

“Fjallkonan” presented various kinds of garbage, including a long story, “Powers of Darkness.” That story would have been better left unwritten, and I cannot see that such nonsense has enriched our literature.25

Valdimar, on the other hand, promoting the liberalization of trade relations with England,26 hoped to connect his readers with the newest literary trends from the U.K. and attract more subscribers to his newspaper. Publishing Makt Myrkranna was part of Valdimar’s strategy to offer more quality content to his readers, at the same time raising the subscription price from 3 to 4 Crowns.27

After Valdimar’s early death at age 50, in April 1902, Bríet took over the management of Fjallkonan. The first edition of Makt Myrkranna, originally planned as a bonus present for new subscribers, was sold off; copies of this book are extremely hard to get today, as most of them are in the hands of universities or public libraries.28

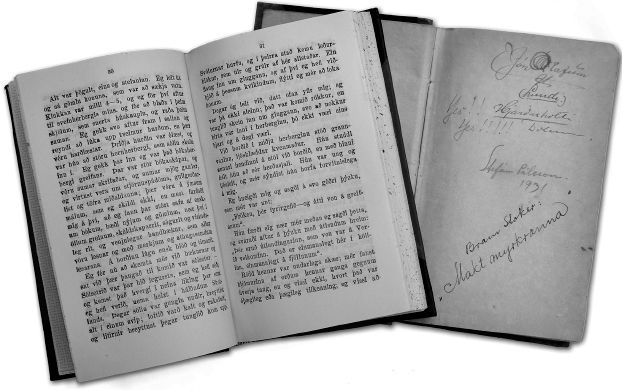

Two copies of the first book edition, 1901 (collection of the author)

Despite the lack of positive reviews, Makt Myrkranna seems to have penetrated the Icelandic cultural consciousness. When Tod Browning’s Dracula was shown in Reykjavík in 1932, a newspaper announced the movie as “based on the fiction story of ‘Makt Myrkranna’ which has been published in an Icelandic translation that will be familiar to many people.” Similarly, Vísir of 18 December wrote under the title Dracula: “Nýja Bió has recently shown a movie with this name, which is based on the story ‘Makt Myrkranna,’” a comment suggesting that the story of the bloodthirsty Transylvanian count was originally invented in Iceland and that the Americans had copied it. Over the decades, “Makt Myrkranna” has become in Iceland the standard nomenclature for all sorts of Dracula films, showing that Valdimar’s book was much better known than can be judged from Benedikt’s single review. Maybe due to the general recognition of the title, Hogni Publishers launched a second edition in 1950.

In 1975, Halldór Laxness, the Icelandic Nobel Prize winner for Literature who was fascinated by the Dracula myth, urged:

And do not forget Makt Myrkranna (Bram Stoker) with the famous un-dead Count Dracula in the Carpathians, which was not less popular than today, and one of the best pens of the country was engaged to translate the novel: Valdimar Ásmundsson (ed. 1901).29

But: was Valdimar Ásmundsson really only the translator of the story? Until Ásgeir Jónsson, the editor of the third Icelandic edition, in 2011 addressed the deviations from the text of Dracula, only two scattered lines in the Icelandic press indicated that anyone had noted a difference between English and the Icelandic plot lines at all.30

For those who know Dracula, Makt Myrkranna awaits with some major surprises. The most obvious one is that the account of Harker’s trip to Transylvania has been expanded from approx. 22,700 words in Dracula to approx. 37,200 words in Makt Myrkranna—a 63% increase in length. The rest of the story, on the other hand, has been cut down from 137,860 words to only 9,100—a 93% reduction. This massive shift of proportions alone forbids calling Makt Myrkranna an “abridged translation” of Dracula. The Transylvanian part has not been shortened at all, while the rest of the story has shrunk to a mere coda. We can only speculate about the “why.” Maybe Valdimar was working from a proto-version of Dracula that Stoker never worked out to the end. Maybe he lost his patience with Stoker’s lengthy story, which had been filling his magazine for over a year, and thus decided to speed up the final part. We know that in the 1980s, the 1897 typescript for Dracula was found in a barn in Pennsylvania, with the first 100 pages missing;31 it has been speculated that these contained a more elaborate start of the novel, eventually worked out as the short story Dracula’s Guest, published by Bram’s widow in 1914. There may have existed other, still earlier, drafts for Dracula, based on the notes Stoker made from March 1890 on.

The second major difference between Dracula and Makt Myrkranna is that in Part II, the epistolary format—which often has been considered Dracula’s outstanding characteristic—has been abandoned. In Dracula, the story unfolds through a series of diaries, newspaper reports, and letters, usually penned by the novel’s main characters. But in the Icelandic version, we are guided through the story by an all-knowing narrator. This is a major deviation from Stoker’s initial concept, and also from the Icelandic preface, which states “otherwise I leave the manuscript unchanged”—which can only mean that the author merely wishes to introduce a manuscrit trouvé, written by the people playing a role in the story, without giving up the epistolary structure. Although for the understanding of the plot, this change of format does not matter much, it forces the reader to wonder whether Stoker stepped away from the diary format himself, or if Valdimar was responsible for this.

The plot of Makt Myrkranna also contains new elements, while large parts of the Whitby and London episodes have been omitted and the chase of the whole party across Europe, through Moldavia and Transylvania, has been cut out completely.

In Dracula, Harker’s only company during his visit to Castle Dracula is the Count himself, except for a short interlude with three provocative female vampires. In Makt Myrkranna, the young lawyer (here named Thomas) is welcomed to the castle by a mysterious old woman acting as the Count’s housekeeper. Soon after, a seductive blonde vampire girl starts to play a major role in Harker’s desperate existence; their repeated secret meetings become ever more intimate and the prudish Englishman proves to be more than just a passive victim. Moreover, the Count shows Harker a gallery with family portraits, granting insight to the Transylvanian’s social-Darwinist philosophy and providing a rich sub-plot of intrigue, passion, adultery, and revenge—seemingly inspired by the life of Joséphine de Beauharnais, Napoleon’s wife. During his explorations of the castle in Makt Myrkranna, Harker discovers a murdered peasant girl and a secret passageway leading to a hidden temple, where he witnesses an archaic sacrificial ceremony headed by the Count himself. Instead of being a mere solitary relic of medieval war times, as was Stoker’s Count, Thomas Harker’s host not only commands a large crowd of ape-like devotees but also finances and masterminds an international diplomatic conspiracy, aiming to overthrow Western democratic institutions. In the London part of the story, the Count, acting under various pseudonyms, also entertains a large number of high-ranking guests in his lavishly furnished Carfax residence, where he is always surrounded by the most stunning and elegant young women.

Intriguingly, the end of the Icelandic story almost runs parallel to the later stage and movie versions. This also applies to the more elegant public appearance of the Count—vampire cape included. More research would be needed to understand how Makt Myrkranna could anticipate changes made by playwright Hamilton Deane and screenwriter John Balderston a quarter of a century later. Despite the shortened ending, the second part of Makt Myrkranna also introduces a series of new characters, including Lucy’s uncle Morton, Hawkins’s agent Tellet, and the police detective Barrington. Various foreign aristocrats, such as Prince Koromezzo, Countess Ida Varkony and Madame Saint Amand, also make an appearance, while Dracula’s Renfield character and Mina’s “blood-wedding” with the Count are eliminated.

But even more than the changed format, the added events, and the extra characters, the altered style of the novel seems the most significant innovation to me. In the Icelandic text we find no legal discourses nor lengthy sentimental dialogues; instead, it features a number of virtually denuded young girls, absent in Stoker’s Dracula and other texts.32 Moreover, there are several elements added from the Icelandic sagas, with which Valdimar was far more familiar than Stoker; I suspect that Valdimar included these references himself and some of them are so subtle that only someone familiar with Norse literature would recognize them. The overall change of style is so obvious, however, that we may safely assume that Valdimar must have shaped the Icelandic narrative to a high extent, instead of merely translating.

An extra bonus in this translation is the chapter that was published in Fjallkonan of 13 October 1900 but left out of the 1901 book printing and its second and third editions. This episode focuses on Harker’s emotional dependency on the nameless blonde vampire girl who occupies the castle’s top floor. We do not know why it was omitted later—or why it was even written in the first place: it has no equivalent in Dracula and more or less interrupts Harker’s account of the legal studies he has taken up in the Count’s library. More than any other chapter, however, it shows Harker’s feelings and his strong attachment to his fiancée, named Wilma here, while he is being drawn toward the indescribably gorgeous girl against his will. In this sense, Makt Myrkranna is a stronger love story than Dracula, where vows and prayers replace real intimacy. Although in Stoker’s original, Jonathan Harker is initially thrilled by the vampire ladies, after his first encounter with them he is only disgusted, and he sees the Count as his savior for interrupting their seductive advances. His counterpart Thomas in the Icelandic version, however, constantly longs to be reunited with the fair-skinned temptress and allows her to embrace and kiss him time and time again, and even sit on his lap; in these and in other scenes, the women in the story seem to be attractive to the point of being irresistible—there are no traces of the physical revulsion expressed in Dracula and in Stoker’s later novel, The Lair of the White Worm (1911). A strange complicity unites Thomas and the slender sylph in their joint resistance against the Icelandic Count, who appears as a punishing father figure separating the romantic couple. Physically, the King of Vampires seems to be no direct threat to Thomas—at least not a willing one.33 The acts of biting and drinking blood are undertaken by the ape-like minions, whose violence lacks the sophistication and discretion of their aristocratic overlord. We never surprise the Count with his teeth in someone else’s neck and after Lucia (Makt Myrkranna’s version of Lucy) dies (no bite marks having been noticed), he does not come after Wilma. The Count and his conspiracy seem not to aim at a bloody killing or two, but at overthrowing the democratic governments of Europe. The terror, in the Icelandic version, is less personal.

3. THE HINT AT THE RIPPER MURDERS

The preface to Makt Myrkranna, signed with Stoker’s initials “B.S.,” seems to confirm that the author of Dracula generally approved of this alternative edition and was familiar with at least some of the major new plot elements. The comment about remarkable foreigners playing a dazzling role in London’s aristocratic circles, for example, does not match the plot of Dracula, but exactly fits the—modified—Icelandic version: it points to the foreign guests involved in the Count’s political conspiracy, driving around town in eye-catching carriages, showing off their jewelry and enjoying amorous liaisons in the highest circles of power.

The part of the Makt Myrkranna preface that received the most attention from Dracula scholars is the remark about the Ripper murders. In Dalby’s translation:

But the events are incontrovertible, and so many people know of them that they cannot be denied. This series of crimes has not yet passed from the memory—a series of crimes which appear to have originated from the same source, and which at the same time created as much repugnance in people everywhere as the murders of Jack the Ripper, which came into the story a little later. Various people’s minds will go back to the remarkable group of foreigners who for many seasons together played a dazzling part in the life of the aristocracy here in London; and some will remember that one of them disappeared suddenly without apparent reason, leaving no trace.

These words have puzzled Dracula experts for decades, as Dracula never mentions the Ripper. In fact, it describes no coherent series of crimes that—as this preface suggests—might have caused widespread concern, as the Ripper Murders did. In Whitechapel of the late 1880s, women were warned not leave their homes alone after dark; vigilante troops patrolled the street, inspecting the narrow alleys, which were not gaslit, as today’s movies might have you believe, but simply dark and deserted. Newspapers competed to present the grisliest details, the latest drops of blood splattered on the walls of London’s East End, and launched ever-new speculations about the “butcher” terrorizing “women of the unfortunate class.”

In Dracula, we are confronted with the demise of the Demeter crew and with the deaths of Mr. Swales, Renfield, Lucy and her mother. But in the eyes of the police and the general public, these events all seem completely unrelated.34 Why, then, would Stoker have added this puzzling reference to the Makt Myrkranna preface?

Dalby’s translation suggests that the Ripper Murders appear in the novel “a little later,” that is, somewhere after the preface. As a result, many Dracula scholars have started to search for obscured references to the Ripper Murders in the text of Dracula. But Dalby’s translation is incorrect, and moreover, to understand what the Icelandic preface hints at, we should read the text of Makt Myrkranna, not that of Dracula.

Instead of “the murders of Jack the Ripper, which came into the story a little later,” the preface speaks of “the murders of Jack the Ripper, which happened a little later.” This means that “this series of crimes [that] has not yet passed from the memory” is a series of slayings that started before the Ripper Murders, and in their time (not “at the same time”—another error in the Dalby translation) also caused terror with the public, and in the imagination of the London population seemed to be connected with the Whitechapel homicides. Which crime series can be meant here?

In Makt Myrkranna, Harker’s Journal of 8 May describes how the Count discusses a London crime spree and refers in particular to “these crimes, these horrible murders, those slaughtered women, found in the Thames, drifting in sacks; this blood that runs—runs and flows—with no murderer to be found.” Beyond a reasonable doubt, this highly specific reference can only point to the unsolved “Thames Torso Murders” (1887-89), also known as the “Thames Mysteries” or “Embankment Murders”:

Evidence that a killer was at work first showed up in May of 1887, in the Thames River Valley village of Rainham, when workers pulled from the river a bundle containing the torso of a female. Throughout May and June, numerous parts from the same body showed up in various parts of London – until a complete body, minus head and upper chest, was reconstructed. (….)

The second victim of the Thames series was discovered in September of 1888, in the middle of the hunt for the Whitechapel Murderer. On September 11, an arm belonging to a female was discovered in the Thames off Pimlico. On September 28, another arm was found along the Lambeth-road and on October 2, the torso of a female, minus the head, was discovered.35

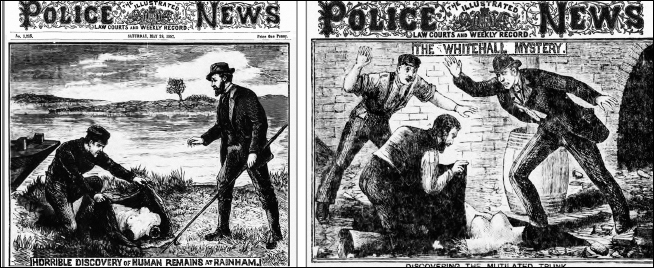

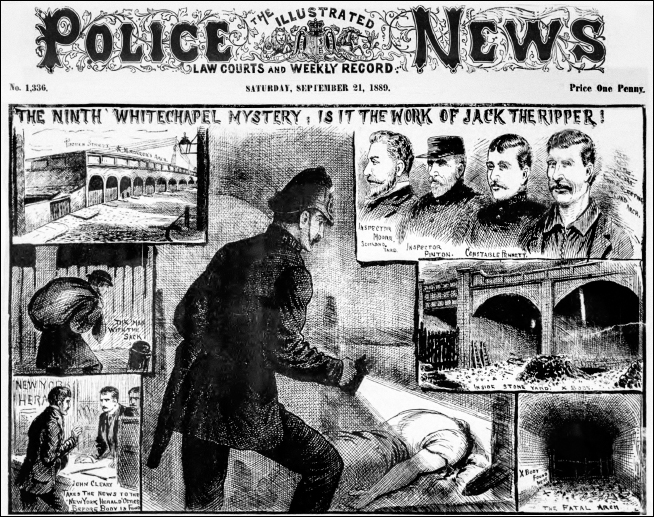

Bottom left: The first trunk of a young woman found in the Thames near Rainham, on 28 May 1887. Further body parts were found in the course of 1887. Right: On 2 October 1888, during construction of the Metropolitan Police’s new headquarters on the Victoria Embankment near Whitehall (Westminster), a worker found a parcel containing human remains. Newspapers suggested a connection to the Whitechapel Murders, but the police linked the crime with the Rainham Mystery.

These “Thames Mysteries” indeed triggered as much public unrest as the Ripper Murders were to cause one year later. And when female torsos were found at the construction site of Scotland Yard(!) in October 1888 and under a railway arch in Whitechapel in September 1889, some newspapers suggested that one and the same perpetrator could be responsible for both series of crimes. Although no more details of the Thames Torso Murders are given in the London part of Makt Myrkranna, it is not hard to imagine that the Count’s London vampire coven, abducting fresh victims for their satanic rituals, disposed of the dead bodies by dumping them into the river—especially if the Count’s Carfax house was located in London-Plaistow (as in Stoker’s original concept), not far away from Rainham, where the first Torso Murder victim was found. If nothing else, the fact that the murderer could not be found seems to comfort Valdimar’s Count, who apparently relishes the idea that in the darkness and fog of London’s streets, his own crimes may go unsolved.

The “canonical” Ripper Murders took place from May–November 1888, but when on 10 September 1889 a female torso, wrapped in some sacking, the belly cut up, was found under a railway arch in Pinchin Street, Whitechapel, about 1,000 meters from the Thames, it was speculated that the Ripper had returned, although the police categorized the crime as one of the Thames Mysteries. Some newspapers speculated that the Whitechapel Murders and the Thames Mysteries might have been committed by the same murderer, using different ways to dispose of his victims. This is the basis for the remark in the Icelandic preface about the discussed murders seemingly stemming from the same root as the Ripper Murders.

Last but not least, the preface’s mention of the secret police only makes sense in the context of the international political scandal that must have followed the uncovering of the Count’s machinations—a plot point unique to Makt Myrkranna and another indication that Stoker was aware of the planned innovations.36

4. THE NAMES OF THE NEW CHARACTERS

A further clue that seems to confirm that Bram Stoker actively participated in reshaping his vampire novel lies in the names of the newly added characters. Some names could easily have been created by Valdimar, inspired by wordplay or geography.37 The names of the police detective, Barrington, and Hawkins’s assistant, Tellet, however, seem a bit too particular to have been randomly invented by an Icelandic author. My guess would be that, like other names appearing in Dracula, these designations may have been borrowed from people Stoker knew.

Sir Charles Burton Barrington captained Trinity College’s rugby football team from 1867 till 1870; Stoker studied there 1864-1870 and played on the rugby team. Benjamin Barrington was one of the Trinity students linked to a nighttime shooting that killed a professor in his own house at the Trinity Campus, in March 1734. This Barrington became notorious for influencing witnesses during the trial and his name still belongs to Trinity’s campus lore.

For “Tellet,” an extremely rare name occurring only five times in the 1891 census for England, Wales, and Scotland, I also found a plausible link. On 23 April 1837, the comedy actress Clarissa Anne Chaplin married Daniel John Tellet at St. John’s Church in Liverpool and became known as “Mrs. C. A. Tellet” or—for the stage—as “Miss Clara Tellet.” In Fifty Years of an Actor’s Life (1904), her colleague John Coleman described her as “Miss Clara Tellet, who was a perfect pocket Venus, and one of the brightest and most vivacious of soubrettes. This fairy-like creature ultimately became Mrs. Sam Emery and mother of the charming Winifred of that ilk (Mrs. Cyril Maude), who has inherited no small share of her mother’s charm.”38 Samuel (“Sam”) Emery performed in Not Guilty at the Queen’s Theatre (1869) together with Henry Irving, Stoker’s later employer. Sam and Clara’s daughter Winifred Emery played female lead roles at the Lyceum Theatre next to Ellen Terry from 1881 to 1887 and toured America twice with Irving and Stoker.

Charles Burton Barrington (center, with the ball) and his rugby team

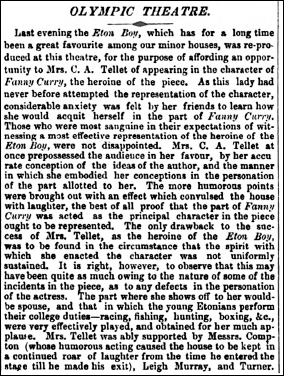

The Morning Advertiser of 14 Nov. 1848

The name of Varkony, which appears only in the Icelandic version, may also have sounded familiar to Stoker, from stories his mother told of her home county, Sligo. On 11 April 1811, the aristocrat Francis Taaffe married Antonia Amadé Varkony of Hungary, while Taaffe’s sister Clementina on the very same day married Count Thaddaeus Amadé Varkony, Antonia’s cousin.39 Taaffe bore the title of “Baron of Ballymore” in County Sligo. Perhaps, Bram’s mother reported on the curious double wedding.

The most intriguing connection, though, concerns the character—again new to Makt Myrkranna—of Holmwood’s sister Mary. Possibly, Stoker took it from the writer Mary Singleton (whose name already appeared in Stoker’s early notes for “a psychical research agent, Alfred Singleton”), famous in London literary circles for her beauty and witty conversation. She played a prominent role as the unhappily married Mrs. Sinclair in W.H. Mallock’s roman à clef, named The New Republic (1877). Mary Singleton was unhappily married indeed: after being rejected by her lover, she married the elderly Henry Sydenham Singleton, but in the early 1880s exchanged secret vows with Philip Lord Currie of the Foreign Office, and also had an affair with Philip’s cousin. In well-informed circles, to which also Stoker belonged,40 her liaison with Sir Philip became a public secret—especially as she hinted at her luckless situation in The Edwin and Angelina Papers41 and in her novel The Adventures of a Savage (1881). The latter dealt with a young woman bored with her elderly husband and betraying him with a younger lover; the story had a happy ending when the “old squire” died and the heroine was reunited with her “young squire.” Appropriately, Henry S. Singleton died in March 1893 and within ten months Mary had married Sir Philip Currie, the newly appointed Ambassador to Constantinople. The couple moved to Constantinople only a few days after their wedding.42The similarities between Mary Singleton’s story and the plight of Makt Myrkranna’s Mary Holmwood are striking and unique.43

Count Thaddaeus Amadé Varkony

Mary Singleton, née Montgomerie Lamb (Violet Fane)

5. BRAM STOKER’S PREPARATORY NOTES FOR DRACULA

Still another point suggests Stoker’s active contribution to the Icelandic version. In what will come as a surprise to every Dracula scholar, plot elements that were described in Stoker’s early preparatory notes for the novel, but did not appear in the book, are found in Makt Myrkranna:

If we are not prepared to accept these seven similarities between Stoker’s notes and the new plot elements in Makt Myrkranna as a mere coincidence, Bram Stoker must have passed his early plot ideas to Valdimar.

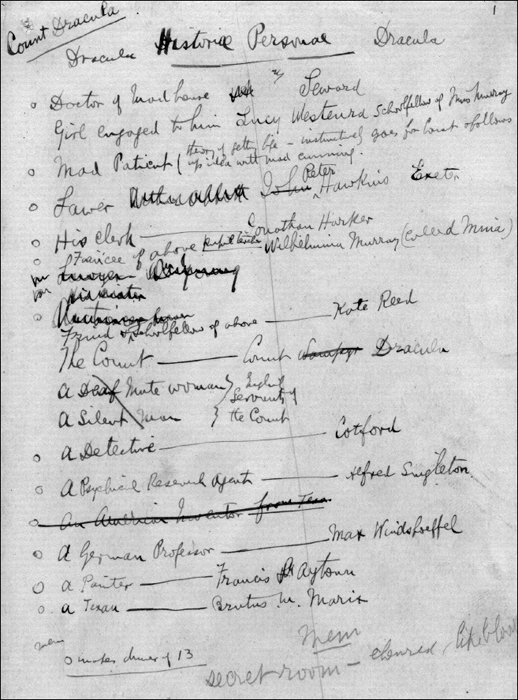

Handwritten list Historiae Personae, from Bram Stoker’s notes for Dracula

6. THE MYSTERIES OF THE PREFACE

How can we be sure that Bram Stoker wrote the preface himself and thus was aware of at least some of the changes to his story?

One important authorship clue is that the preface highlights Van Helsing as a “real” person, appearing under a pseudonym. If Valdimar wrote the preface on his own account, he must have read an interview with Bram Stoker in The British Weekly of 1 July 1897—the only known document describing Van Helsing as “based on a real character.” The chances that Valdimar ever came across this interview are small, however: in the Icelandic press, the magazine was only mentioned in 1912 for the first time and the National Library of Iceland in Reykjavík never had a subscription to it. Moreover, the author of the preface must have known about the rumors in the London newspapers that the Thames Torso Murders and the Ripper Murders might stem from the same root. Bram Stoker, living in London and forced to cancel the performances of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde at his Lyceum Theatre due to the general Ripper panic, was likely to be familiar with such theories. By contrast, neither Fjallkonan nor the rest of the Icelandic press ever mentioned the Embankment Murders. And even if Valdimar had studied the Torso Murders, why should he confuse his Icelandic readers with an obscure hint that they would never have been able to understand? The Hamlet quote also reeks of Stoker: Irving performed the role of the Danish prince hundreds of times and Dracula contains several allusions to the play. All in all, it seems apparent that Stoker gave the Icelandic project his blessings and was informed about the new direction the story would take, but did not know all the details.44

Another important indication is that the preface is dated and signed: “Lundúnu, ––––– stræti, Ágúst 1898, B.S.”45 It would have been a severe—possibly criminal—act of fraud for anyone else but Stoker to sign that way. Up till 1947 Icelandic publishers were not bound by the Berne Convention.46 Stoker thus had no legal means to enforce his copyright in Iceland and prevent an unlicensed translation or even a modification of Dracula there. But fabricating a phony preface and signing it off with Stoker’s name—but without his endorsement—would add a whole new dimension of literary piracy: Valdimar would not only damage Stoker, but also hoodwink his own readers and impersonate another writer—no trivial offense in Iceland, where literature plays a central role and straightforwardness is a highly valued virtue.

A last clue is the assessment by Ásgeir Jónsson, the editor of the 2011 Icelandic edition, with whom I exchanged ideas about Stoker’s and Valdimar’s role in Makt Myrkranna in early 2014.47 In Ásgeir’s opinion, the Icelandic of the preface deviates from the style of the novel; it is less fluent, as if Valdimar had translated a text from a foreign language:

Valdimar Ásmundsson had a way with words and an extremely good command of his mother tongue. Our Nobel laureate, Halldór Laxness, has called him the “best pen in the whole of Iceland in the beginning of the twentieth century.” The translation of Dracula itself, although not loyal to the original text, is written in an extremely vivid and skillful way—that is why I decided to republish it. However, the preface is very clumsy, the sentences are very un-Icelandic and unlike Valdimar—they have much more of an English character.48

This assessment by a native Icelandic speaker and author supports the idea that the preface was written by Stoker and then translated, instead of being concocted by Valdimar.49

7. WHO CONNECTED VALDIMAR AND BRAM STOKER?

In the foreword to this book, Dacre Stoker mentions the possibility that Bram Stoker’s friend Hall Caine had been instrumental in connecting Stoker and Valdimar. Caine wrote two novels set in Iceland and visited the country twice—in 1889 and again in 1903; the second time he was invited to an official dinner organized by the Icelandic government.50 He admired William Morris’s renderings of the Icelandic sagas and may have been in touch with Valdimar, a specialist on this topic.

It is also possible that Mark Twain established the link. Although Twain never was in Iceland himself, in 1884, 1885 and 1886 respectively, three of his short stories were translated and published in Iðunn, a literary magazine run by the poet and teacher Steingrímur Thorsteinsson, the journalist Jón Ólafsson and by Björn Jónsson, the editor of Ísafold;51 all three were friends of Valdimar. In 1893, Fjallkonan published a fragment from Twain’s The Innocents Abroad (1869)52 and in 1894, it serialized The Million Pound Banknote.53 During his trips to America with the Lyceum Theatre, Stoker and Twain had become good friends. From early October 1896 till June 1897, Twain and his family lived just a stone’s throw away from Stoker’s house at St. Leonard’s Terrace.54 In spring 1898 Stoker offered to act as Twain’s dramatic agent in the U.K. and look through his play Is He Dead?55 From June 1899 until October 1900, Twain and his family lived in London again. It therefore would not be unlikely that Twain passed his Reykjavík contacts to Stoker.56

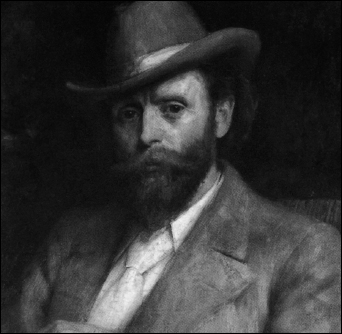

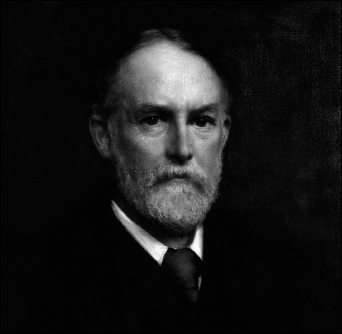

Thomas Hall Caine

(Painted by Robert Edward Morrison)

Mark Twain

(Photo: Associated Press)

It may also be that Frederic Myers, the secretary of the Society for Psychical Research, had given Stoker a hint. The S.P.R. had been founded by scholars gathering around Henry Sidgwick, a Cambridge philosophy professor since 1874. Their goal was to perform scientific research on paranormal phenomena. Spiritism was en vogue in Victorian London and many honorable citizens spent their evening around a table while a—usually female—medium apparently received messages from beyond through the Ouija board or table-lifting. As the society’s researchers found out, many professional mediums had developed ingenious tricks to move tables with sophisticated mechanisms or sheer body control. In 1895, for example, Frederic Myers, Oliver Lodge and Richard Hodgson exposed the celebrated medium Eusapia Palladino, proving that she had been manipulating furniture with her feet during her séances.57The Society counted as many as 1,400 members and reported on their experiments and meetings in their famous Proceedings. Stoker was friends with such prominent S.P.R. members as Alfred Tennyson, John Knowles, William Ewart Gladstone, and Arthur Conan Doyle. On 9 September 1890, Valdimar dedicated the complete front page of Fjallkonan to the S.P.R. and extensively discussed Myers’s book Phantasms of the Living.58 In June 1898, Stoker and Irving lodged at Myers’s house, along with Lord Dufferin,59 the author of the international bestseller Letters from High Latitudes, recounting Dufferin’s visit to Iceland.60 Is it possible that Myers, entertained by Dufferin’s adventures, mentioned the leading Icelandic newspaper that had shown so much interest in his paranormal research—a most suitable platform for Stoker’s supernatural novel?61

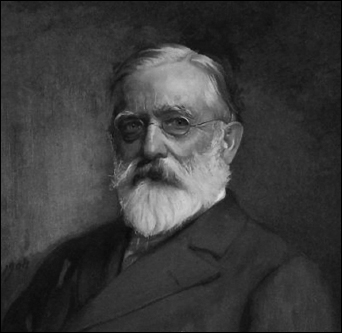

Frederic William Henry Myers

(Painted by William Clarke Wontner)

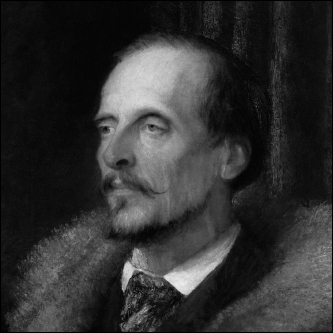

Daniel Willard Fiske

(Painted by Cei Cipriano)

As long as no letters between Bram Stoker and Valdimar Ásmundsson (or manuscript versions or notes etc.) are found, the debate about the Irishman’s personal contribution to Makt Myrkranna will continue and maybe even split the field of Dracula scholars—like the mysterious identity of Count Dracula once did.

For the outstanding quality of the novel, however, this makes no difference; in the pages that follow, the reader can enjoy the story, including such vivid scenes as the tribal ceremonies in the Count’s hidden temple.62

Lord Dufferin

(Painted by George Frederic Watts)

It is the combination of Stoker’s original ideas—as documented in his notes—with original contributions by Valdimar Ásmundsson and daring innovations anticipating later movies and screenplays, that makes Makt Myrkranna such an intriguing literary work. Regardless of the mysteries attached to its creation, the novel can now be read by readers all over the world, who may make their own discoveries in the text.

Hans C. de Roos

Munich, March 2016