Chapter 2

Hieroglyphs, Language, and Pharaonic Chronology

2.1 Language of the Ancient Egyptians

The ancient Egyptians spoke a language which is now called Egyptian. No one knows the correct pronunciation of this language, which in any event changed greatly over the course of several thousand years (as did the written language), and there were probably regional dialects and variations in pronunciation as well. The language is known only through its various written forms, the most formal of which is the pictorial script called hieroglyphic. The Greek word “hieroglyph” literally means “sacred writing,” an appropriate term for a writing system that was used on the walls of temples and tombs, and which the Egyptians themselves called the “god’s words.”

Linguists classify languages by placing them in families of related languages, such as the Indo-European family, which includes English and many European and Asian languages. Ancient Egyptian is a branch of the language family called Afro-Asiatic (also known as “Hamito-Semitic”). Ancient languages of the Afro-Asiatic family, such as Egyptian, are known only from preserved written texts, whereas many Afro-Asiatic languages spoken in northern and eastern Africa and recorded in recent times have no earlier written form.

The Semitic languages form the most widely spoken branch of the Afro-Asiatic languages, and include ancient languages such as Akkadian (an “East Semitic” language spoken and written in ancient Mesopotamia, in a script called cuneiform, which means “wedge-shaped writing”), and Hebrew (one of the “Northwest Semitic” languages of Syria and Palestine, of the first millennium BC). Semitic languages spoken today include Arabic and Hebrew, as well as several languages of central and northern Ethiopia and Eritrea.

Other branches of the Afro-Asiatic language family include Cushitic, Berber, Chadic, and Omotic. These names relate to peoples and regions in Africa where these languages are spoken. Berber and Cushitic are geographically closest to Egypt. One of the Cushitic languages is Beja, which is spoken by nomadic peoples in the Eastern Desert, and has some close analogies to Egyptian.

2.2 Origins and Development of Egyptian Writing

Although Egyptian was certainly one of the languages spoken in the lower Nile Valley in prehistoric times, the first writing of the language did not appear until about 3200 BC. The earliest known hieroglyphs appear at the same time that a large state was consolidated and controlled by the first Egyptian kings. From the beginning the writing system had a royal context, and this is probably the setting in which writing was invented in Egypt. It used to be proposed that writing was first invented in Mesopotamia and then the idea of writing diffused to Egypt. The structure, scripts, media, and uses of the two writing systems, however, are very different, and it seems more likely that writing was invented independently in both Egypt and Mesopotamia.

In use for over 3,000 years during pharaonic and Greco-Roman times, spoken Egyptian changed through time (Figure 2.1). These changes are reflected to some extent in the written language (Figures 2.2 and 2.3). Early Egyptian is the earliest, formative stage of writing and dates to Dynasty 0 and the first three dynasties. The earliest hieroglyphs are found on artifacts from tombs: royal labels that were probably attached to grave goods, royal seals, and labels of high state officials. Hieroglyphs are also found on early royal ceremonial art, the most famous of which is the Narmer Palette (Figure 5.6). The use of these signs was not standardized. Writing at this time was used to record words as items of information rather than consecutive speech, with verbal sentences, syntax, etc., and the earliest writing remains incompletely understood because there simply is not enough material.

Figure 2.1 Stages of the Egyptian language.

Source: Antonio Loprieno, Ancient Egyptian: A Linguistic Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995, p. 8. Reprinted by permission of Cambridge University Press.

Figure 2.2 Fragmentary papyrus in hieratic about the Battle of Qadesh, fought by Rameses II in the 19th Dynasty (E. 4892).

Source: The Art Archive/Musée du Louvre Paris/Dagli Orti.

Many more texts are known from the Old Kingdom (4th–6th Dynasties), in a form of the written language known as Old Egyptian. In combination with scenes, hieroglyphic texts appear on the walls of tombs of private individuals, and in the later Old Kingdom, the earliest royal mortuary texts, known as the Pyramid Texts, are found in the inner chambers of pyramids. Full syntax was being written down at this time.

Middle Egyptian (also known as Classical Egyptian) is the written language of the Middle Kingdom (later 11th and 12th–13th Dynasties) and Second Intermediate Period. This is the classical period of ancient Egyptian literature, when literary texts such as the Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor and the Story of Sinuhe were composed. Instructional texts in mathematics, medicine, and veterinary practice are known, as well as letters, legal documents, and government records. Religious texts were written in Middle Egyptian, not only in the Middle Kingdom, but also in later periods. Developing as part of the same large corpus as the late Old Kingdom Pyramid Texts, mortuary texts for private individuals were painted or incised on the sides of Middle Kingdom coffins, hence the term Coffin Texts. New Kingdom mortuary texts are also mainly in Middle Egyptian, including the so-called Book of the Dead (more correctly known as the Going Forth by Day) and the underworld books found on the walls of royal tombs. Approximately 700 different hieroglyphic signs were used to write Middle Egyptian (but no single text would ever be written with so many different signs).

Late Egyptian is the written language of the later New Kingdom (19th–20th Dynasties) and Third Intermediate Period. Although it had been spoken for a long time, Late Egyptian did not appear as a fully written language until later in the 18th Dynasty, during the reign of Akhenaten. The huge body of monumental texts on the walls of New Kingdom temples continued to be written in a form of Middle Egyptian. Numerous surviving government records include the account of a workers’ strike, and many types of texts known earlier, such as literary works, letters, and medical and magical texts, are written in Late Egyptian.

Demotic is the written language (as well as a script) associated with the Late Period, beginning with the 26th Dynasty (664–525 BC), and it continued to be in use through Greco-Roman times. A large body of Demotic literature is known, especially narrative and instruction texts. The latest known use of Demotic is from a graffito at the temple of Philae, dating to AD 452.

The latest (and last) form of the ancient Egyptian language is Coptic, which began to be written in the 2nd century ad ( Figure 2.3). Since hieroglyphs were associated with pagan temples and practices in Egypt, Egyptian-speaking Christians wrote in Coptic, using the Coptic alphabet, which was derived from the Greek alphabet, with the addition of a few letters derived from demotic script. The last hieroglyphs are from the late 4th century AD, after which knowledge of this ancient writing system was lost. Gradually after the Muslim conquest of Egypt in the 7th century, Arabic began to replace Coptic as the spoken and written language. Coptic continues to be used as the liturgical language of the Egyptian Coptic Church.

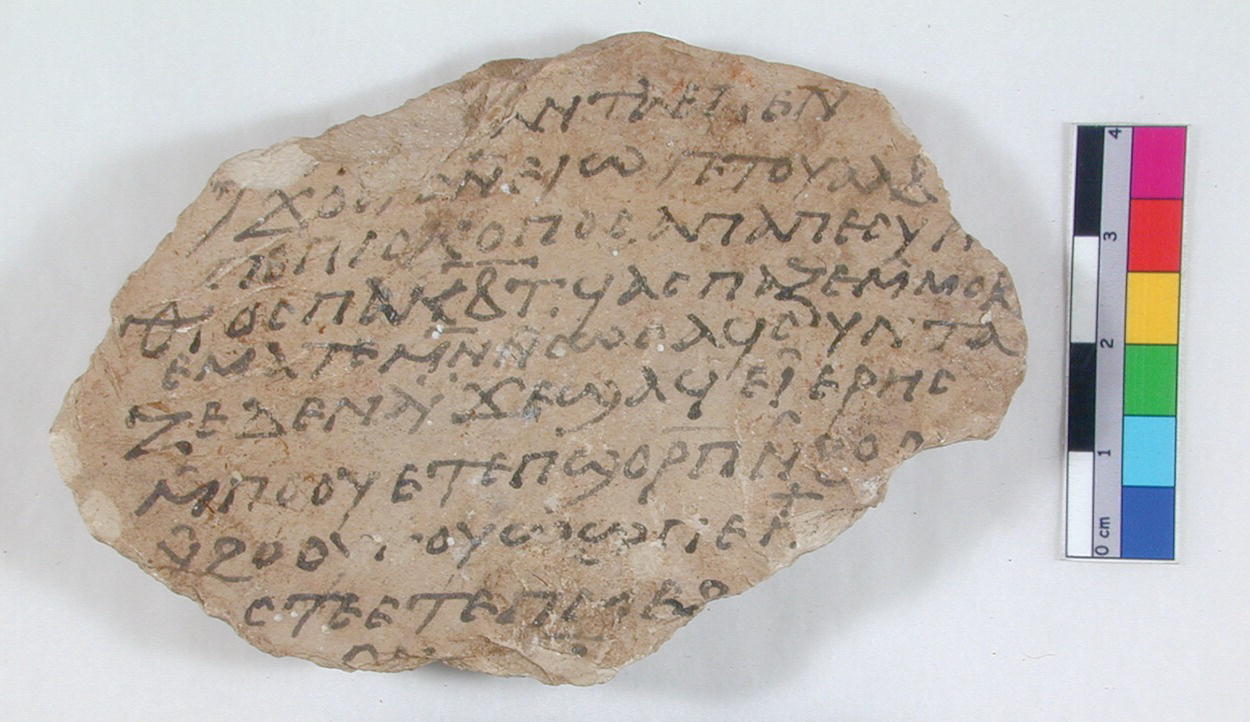

Figure 2.3 Limestone ostracon, with Coptic inscriptions on both sides, addressed to Psan, probably the disciple of Epiphanius, and naming Pesentius of Coptos/Qift.

Source: © Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, University College London UC62848.

2.3 Scripts and Media of Writing

Ancient Egyptian was written in different scripts, depending on the media and the time period. Hieroglyphs are the pictographic signs that appeared from the earliest times when writing was invented in Egypt. Hieroglyphic signs never became abstract and were the most formal script, of symbolic importance for all monumental texts, both religious and mortuary. Hieroglyphic texts were carved on the walls, ceilings, and columns of stone temples, and on many types of artifacts. They were also painted or carved on the walls of tombs, and were used to record many religious texts on papyrus.

At the same time that early hieroglyphs were used, a more cursive and informal script now called hieratic developed. Written in ink and not carved, hieratic was easier to write than the pictographic hieroglyphs, and is a more abstracted form of these signs (Figure 2.2). Both hieratic and cursive hieroglyphs were used to write texts on papyrus. Records were also written in hieratic on ostraca, broken pieces of pottery or fragments of limestone. Plastered wooden boards were another writing medium, and administrative letters with hieroglyphs written vertically on clay tablets, using a bone stylus, have been excavated in the late Old Kingdom governor’s palace at Balat, in Dakhla Oasis (see 6.12).

The demotic script, which developed in the first millennium BC, was a more cursive form of writing than hieratic. It contains many abbreviations, and has to be read in word groups more than individual signs. The middle text on the famous Rosetta Stone is in demotic, with a hieroglyphic text at the top and Greek at the bottom (Figure 1.1).

2.4 Signs, Structure, and Grammar

With hundreds of signs in use, Egyptian script is much more complex than alphabets, which were not invented in the Near East until the second millennium BC. Egyptian was first written vertically, and horizontal writing did not become the norm until the Middle Kingdom. Signs faced the direction from which they were read, usually from right to left. The script was written with no punctuation between clauses and sentences, and no spacing between words. The system does not write vowels, making it very difficult to reconstruct pronunciation, which is done primarily by working back from Coptic, in which vowels are written.

The use of different classes of hieroglyphic or hieratic signs in the same word made the decipherment of Egyptian much more difficult than it would have been for an alphabetic system. The simplest type of hieroglyphic sign is a logogram, with one sign representing a word, such as the sign  representing the word for “sun.” Some signs (phonograms), many derived from logograms, were used phonetically to represent sounds in the spoken language, with one hieroglyph representing one, two, or three consonants (uniconsonantal, biconsonantal, or triconsonantal signs). Several uniconsonantal signs,

representing the word for “sun.” Some signs (phonograms), many derived from logograms, were used phonetically to represent sounds in the spoken language, with one hieroglyph representing one, two, or three consonants (uniconsonantal, biconsonantal, or triconsonantal signs). Several uniconsonantal signs,  , represent the so-called weak consonants, which were often omitted in writing. Although both biconsonantal and triconsonantal signs appear alone, they are often accompanied by one or two uniconsonantal signs, used as phonetic complements, so that the signs are not to be confused with logographic ones.

, represent the so-called weak consonants, which were often omitted in writing. Although both biconsonantal and triconsonantal signs appear alone, they are often accompanied by one or two uniconsonantal signs, used as phonetic complements, so that the signs are not to be confused with logographic ones.

Determinative signs have no phonetic value and are placed at the end of a word, to graphically convey the general meaning of that word. For example, the determinative sign  depicts a woman giving birth. It is placed at the end of the verb ms

depicts a woman giving birth. It is placed at the end of the verb ms

, “to give birth.”

, “to give birth.”

There are also numerical signs in Egyptian hieroglyphs, which number from one ( ) to 1,000,000 (

) to 1,000,000 ( ).

).

The basic word order of a sentence in Egyptian is: (1) verb, (2) subject (noun or pronoun), (3) direct object. In gender nouns are masculine or feminine, and in number they are singular, dual (for pairs, such as “two hands”), or plural. Adjectives follow the noun and agree in gender and number.

Egyptian verbal sentences can be compound and/or complex, with subordinate clauses, and there are numerous verb forms. There are also non-verbal sentences, in which the sentence structure itself links subject and predicate, and the verb “to be” was understood. Written continuously with no spaces between words or punctuation, individual sentences in texts can only be parsed by applying the rules of grammar. The ancient Egyptian language cannot be described in detail here, and more specific information about its structure can be found in the list of suggested readings.

In the process of translating Egyptian texts, Egyptologists often first transliterate the hieroglyphs or hieratic signs into letters of the Latin/Roman alphabet with spaces left between words. Diacritical marks are used for several consonants with a greater range of phonetic values than exist in European languages and a couple of special signs for consonants that those languages do not possess. The text is then translated into English or another language, which is accomplished with knowledge of the grammar of the form of the language in which the text was written. Even with such knowledge, ancient Egypt is a culture far removed in space and time from the modern world, and concepts expressed in Egyptian texts can remain obscure in meaning, especially in religious and mortuary texts.

Because of the complexities of the language and scripts – as well as the damaged condition of many texts – several years’ training are required to attain full proficiency in ancient Egyptian. Many Egyptologists are full-time specialists in philology, and archaeologists of pharaonic period sites who do not have extensive training in philology need to work with such specialists. It is useful for all specialists of pharaonic Egypt to have some competence in the language – for a better understanding of the textual evidence and what the texts reveal about the culture.

2.5 Literacy in Ancient Egypt

Most people in ancient Egypt did not know how to read and write. Since the majority of Egyptians were peasant farmers, they would not have needed to learn to read, and the complexities of the written language would have made it more difficult to learn than most alphabetic writing systems. Although some members of the royal family and high-status individuals, as well as officials, priests, and army officers, were literate, scribes were needed for operations of the state at all levels.

Egyptian scribes were professionals trained in special schools in royal administrative departments and temples. Some scribes probably learned through apprenticeship, such as is known from the New Kingdom workmen’s village of Deir el-Medina. Model letters recorded by schoolboys, on limestone ostraca and plaster-covered wooden boards, have been found which give us information about what was taught in these schools or to apprentices in jobs. A well-known Middle Egyptian text attributed to the scribe Khety extols the virtues of being a scribe, who will always have employment. He boasts that scribes do not have to wear rough garments like common laborers, and they can take baths. Scribes give orders and others have to obey them.

Scribes were needed for the bureaucratic functions of all branches of the government and administration, including issuing the rations for government personnel and workers who depended on state resources for their livelihood. Tax collection and operations of the treasury needed to be recorded, as did organizing and supplying the personnel for expeditions outside of Egypt – for mining and quarrying, trade, and warfare. Scribes were also used for large-scale state work projects such as pyramid building.

Probably the most visible evidence of writing in ancient Egypt is the hieroglyphic texts found on the walls of temples and tombs, both royal and private. These were the work of artisans who worked with scribes and/or literate artisans. Religious and mortuary texts were written and read by scribally trained priests, and scribes were needed for the construction and operation of temples. Legal proceedings, both local and national, were recorded by scribes. Wealthy private individuals needed scribes to administer their estates and to record documents such as wills and business transactions.

2.6 Textual Studies

The decipherment of Egyptian opened the way to recovering an understanding of the Egyptian language in all of its stages and scripts. An enormous undertaking (which continues in the present) was to record texts of all types for study. After the early 19th-century expeditions, Egyptologists such as Auguste Mariette, Heinrich Brugsch, Émile Chassinat, and Johannes Dümichen continued to record and publish Egyptian inscriptions from major temples, such as Edfu and Dendera. Chassinat published the Edfu temple inscriptions in eight volumes, while publication of the Dendera temple inscriptions continues in the present, by Sylvie Cauville. A monumental project to record Egyptian tombs for the Egypt Exploration Fund (EEF) was undertaken at several sites in Middle Egypt by Norman de Garis Davies (1865–1941) and Percy Newberry (1869–1949). Their work is especially valuable today because many of these tombs are in such a poor state of preservation. James Henry Breasted’s compilation of ancient Egyptian historical records later led to the Oriental Institute’s Epigraphic Survey, which continues in the present (see 1.4).

At the same time progress on understanding the structure and grammar of ancient Egyptian was also being made, mainly in European universities. Adolf Erman (1854–1937) was the first Egyptologist to divide the language into Old, Middle, and Late Egyptian. His translations, as well as those of Heinrich Brugsch (1827–1894), are recognized as the first generally reliable ones. Important contributions in hieratic and demotic were made by Francis Llewellyn Griffith, and in demotic and Coptic by Wilhelm Spiegelberg (1870–1930). Erman was also responsible, along with Hermann Grapow (1885–1967), for the publication of an eleven-volume Egyptian dictionary (1926–1963). Another German scholar, Kurt Sethe (1869–1934), published vast numbers of texts and made impressive contributions in his studies of the Egyptian verbal system, the most complex aspect of the written language.

Alan H. Gardiner’s Egyptian Grammar (1927) continues to be a major work for the study of the classical period of the Egyptian language (Middle Egyptian), but more recently two Middle Egyptian grammars have been published by James Allen (2001) and James Hoch (1997). Hans Polotsky’s 1944 study of Coptic syntax has also had major implications for the study of Egyptian. Work on understanding the Egyptian language and the meanings of ancient texts and words continues to be a very lively area of Egyptology.

2.7 Use of Texts in Egyptian Archaeology

Texts greatly expand our knowledge of ancient Egypt, but they do not give a full view of the culture. Except for the king, high officials, and other persons of high status, socio-economic information about the majority of Egyptians is generally absent from texts. Egyptians believed in the importance of burial, and the participation of many people in yearly religious festivals is well attested. But the personal beliefs of the peasant farmers and their families are not well known.

Texts do not inform us about how effective the ideology of state religion (and its divine king) was in the lives of the average Egyptian, and this can only be gauged through their complicity and participation in the erection of monuments to the king and state gods. The very largest state projects which still impress us, such as the Great Pyramid at Giza, required the conscription, organization, supplying, feeding, housing, and clothing of thousands of workers. But the political and economic organization of the state was probably a much more significant factor for the marshalling of such a labor force than any ideological zeal of the workers for their god-king, about which we know almost nothing.

Textual information is also dependent on what has been preserved over the millennia. Even in such a dry climate as the deserts to either side of the Nile Valley, organic materials used for writing (papyrus, wooden boards, and linen) were much more fragile than inorganic ones. Texts and monuments were often intentionally erased or destroyed, and it was a frequent practice of later kings to usurp or add to the inscriptions of earlier ones. In post-pharaonic times when many sites were abandoned, materials from these sites, including artifacts with textual evidence, were sometimes reused or destroyed – such as the systematic destruction of sacred sites by Christians and early Muslims.

Tomb robbing has been common from ancient to modern times. Most of the Old Kingdom pyramids were probably robbed after the collapse of the state in the First Intermediate Period, and royal tombs of the New Kingdom were robbed during the 20th Dynasty. Unfortunately, tomb robbing has continued into modern times, especially with the rising value of Egyptian artifacts on the international antiquities market. Thus the surviving textual evidence from Egypt, including that of a mortuary nature, is only a very small percentage of what existed at any one period in antiquity.

What textual information has survived is also highly specialized in the information that it conveys. The farther back we go in Egyptian history, the sparser the textual information. Moreover, the early writing, from the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Dynasties, is poorly understood. Although the Giza pyramids are examples of the great accomplishments of Egyptian engineers and architects, there are no texts explaining how these buildings were designed or constructed, and most texts from this period have a mortuary context. But clay sealings and pot marks of kings from the earliest dynasties and later periods are often preserved. If carefully excavated, these sealings and pot marks can be used to date the associated archaeological evidence to the reigns of specific kings, and also provide information about administration and ritual.

Beginning with the Middle Kingdom much more textual information is available than from earlier periods, including letters, government records, and literary texts (some of which are only known in surviving copies from later periods). From the New Kingdom, when there is better preservation of stone cult temples and royal mortuary temples, there are many historical inscriptions. These, of course, present a biased and self-serving perspective. For example, the amount of booty and tribute from Egypt’s conquests abroad was often exaggerated. Ideology dictated that the divine king had to be portrayed as victorious in battle, even when that had hardly been the case. Thus historical fact was revised to idealize the role of the king.

Given that so much textual information from ancient Egypt is lost, and archaeological evidence is always fragmentary, it is important that all available evidence be analyzed within the context in which it was found. Textual evidence is not to be understood simply as factual and needs to be interpreted within its historical and archaeological contexts. Texts add information to archaeological investigations that can be obtained in no other way, such as more specific ranges of dates than are possible with radiocarbon dating (see Box 4-B). Inscriptions are found on many types of artifacts, such as scarabs and servant figures (shawabti), and the names of kings and high officials are stamped on mud-bricks from some New Kingdom sites. Cartouches of kings can sometimes be identified even on fragmentary reliefs and stelae, or impressed on pottery and seals. Thus texts provide much cultural information (often relevant for dating, as well as more specific information about the site) that would not be available otherwise.

Although they were written for elites, the mortuary texts on the walls of tombs and the religious texts on the walls of temples provide much information about beliefs and cult practices that we would not have solely from archaeological evidence. Along with their accompanying scenes, such texts are high in information content and provide a window into ancient Egyptian ideology.

2.8 Historical Outline of Pharaonic Egypt

Dating is one of the most basic concerns in archaeology, and texts of ancient Egyptian king lists are an invaluable source of information for dating pharaonic evidence. King lists must have been available to Manetho, a 3rd-century BC Egyptian priest who first devised a system of 31 dynasties for the almost 3,000 years of pharaonic history. Although modern scholars have demonstrated problems with Manetho’s sequence, which is only preserved in later excerpts, its basic divisions are still followed. Manetho’s dynasties span the time from the beginning of pharaonic history in the 1st Dynasty (ca. 3000 BC) to the end of the domination of Egypt by the Persian Empire, when Egypt was conquered by Alexander the Great (332 BC). Although some dynasties in Manetho’s list correspond to a new ruling family, this is not true for every dynasty.

In the later 19th century, when Egyptian textual and monumental evidence became available to scholars, pharaonic chronology was divided into several major periods (“kingdoms”), when the large territorial state was unified and centrally controlled by a king. These periods are called the Old, Middle, and New Kingdoms. The earliest period of pharaonic civilization consists of the 1st and 2nd Dynasties, now called the Early Dynastic Period (ca. 3000–2686 BC), known as the Archaic Period in earlier histories. Preceding the 1st Dynasty is Dynasty 0, which was first proposed by Werner Kaiser in the 1960s. Kaiser’s hypothesis was later confirmed by excavations of the German Archaeological Institute at Abydos, where tombs of kings who preceded the 1st Dynasty have been identified.

In most periodizations the Old Kingdom consists of the 3rd through 6th Dynasties (ca. 2686–2181 BC). The Middle Kingdom begins with the reunification of Egypt under King Nebhepetra Mentuhotep II of the later 11th Dynasty, and spans the 12th and 13th Dynasties (ca. 2055–1650 BC). The New Kingdom, the age of Egypt’s empire abroad, spans the 18th through 20th Dynasties (ca. 1550–1069 BC). The 19th and 20th Dynasties are sometimes called the Ramessid Period because many of the kings of these dynasties were named Rameses. The dates used in this book are those found in The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, ed. Ian Shaw (2000) (see Box 2-C).

Conventionally the periods of political division between the Old, Middle, and New Kingdoms are called “intermediate” periods. The First Intermediate Period, between the Old and Middle Kingdoms, consists of the 7th through 10th Dynasties, and the earlier 11th Dynasty (ca. 2181–2055 BC). The 7th and 8th Dynasties (ca. 2181–2060 BC) were a short period of about 20–25 years in which a number of kings reigned in the north for a couple of years each. The 9th and 10th Dynasties represent kings whose power base was at Herakleopolis in the Faiyum region, hence this period is sometimes called the Herakleopolitan Period (ca. 2160–2025 BC). The largely concurrent 11th Dynasty (ca. 2160–2025 BC) arose at Thebes and eventually controlled all of Egypt.

The Second Intermediate Period, between the Middle and New Kingdoms, consists of the 15th through 17th Dynasties (ca. 1650–1550 BC). The minor kings of the 14th Dynasty located in the Delta may have been contemporary with either the 13th or the 15th Dynasty. This was a time of divided rule in Egypt, with the Hyksos, ethnically foreign kings of the 15th Dynasty whose origins were in Palestine, controlling northern Egypt, and Egyptian kings of the 16th/17th Dynasties in the south. Later kings of the 17th Dynasty, whose power base was at Thebes, eventually fought northward and ended Hyksos rule there.

The Third Intermediate Period, after the end of the New Kingdom, consists of the 21st through 25th Dynasties (ca. 1069–664 BC). The 21st Dynasty established a new capital at Tanis in the northeastern Delta, while a theocracy ruled by a general, who was also high priest of Amen, controlled the south from Thebes. A later king of the 21st Dynasty (Osorkon the Elder), was the son of a Libyan chief in the Delta, and the kings of the 22nd Dynasty were acculturated Egyptian-Libyans, who attempted to reassert control over all of Egypt. But local rulers of the 23rd and 24th Dynasties also asserted their authority in various centers in the Delta. These dynasties partially overlap in time with the 22nd and 25th Dynasties. The 25th Dynasty (ca. 747–656 BC) is sometimes called the Kushite Dynasty because Egypt and Nubia were controlled by kings of Kush, a kingdom which developed to the far south of Egypt, centered between the Third and Sixth Cataracts of the Nile.

The Late Period consists of the 26th through 31st Dynasties (664–332 BC). In the 26th Dynasty (664–525 BC) Egypt was reunified under kings whose capital was at Sais in the Delta, hence the term Saite Dynasty. In the 27th Dynasty (525–359 BC) Egypt was conquered by Persians of the Achaemenid kingdom whose capital was at Persepolis, in what is now southwestern Iran. The 28th, 29th, and 30th Dynasties (404–343 BC) were a period of successful rebellion against Persian control, and the 31st Dynasty (343–332 BC) is when Persian control was briefly re-established in Egypt.

Destroying the Persian Empire, Alexander the Great of Macedon conquered Egypt in 332 BC. After Alexander’s death in Babylon in 323 BC his empire fell apart. The Ptolemaic Dynasty (305–30 BC) followed when Ptolemy, one of Alexander’s generals, assumed control in Egypt in 323 BC, becoming its first king in 305 BC. The last Ptolemaic ruler was Cleopatra VII (51–30 BC). After her suicide Egypt became a Roman province during what is called the Roman Period (from 30 BC onward). The nominal end of the Roman Period was in AD 395, when the Roman Empire was divided into the East (Byzantine, including Egypt) and West. The combined periods of Ptolemaic and Roman rule are often called the Greco-Roman Period.

The Roman emperors, who seldom visited the country, supported Egyptian religion. Temples for the cults of Egyptian gods (and the emperor as pharaoh) were built during these times and covered with reliefs of the gods and hieroglyphic texts. Egyptian mortuary practices continued as well.

With Rome’s adoption of Christianity in the 4th century AD and its spread though Roman provinces, ancient Egyptian religion and the elaborate beliefs surrounding burial gradually ceased to be tolerated. The Coptic Period (also known as the Byzantine Period), from the early 4th century until the Muslim conquest of Egypt in AD 641, represents the true end of ancient Egyptian civilization. Ancient Egyptian beliefs came to be characterized as pagan, as did the most visible manifestations of ancient culture – the elaborate tombs and temples, and the cult of the god-king.

2.9 The Egyptian Civil Calendar, King Lists, and Calculation of Pharaonic Chronology

Calculation of pharaonic chronology is dependent on knowledge of the methods the ancient Egyptians used to reckon time and record years. Their year had 360 days. Five days “above the year” were added on to make a 365-day year, representing approximately the annual solar cycle. This is called the Egyptian civil calendar because it was used for purposes of the state, such as tax collection and recording the years of a king’s reign. In this calendar, however, there was no calculation of a “leap year” day added on every four years. As a result, the civil calendar moved slowly forward through the real cycle of the year.

An older calendar based on the cycles of the moon had three seasons of four months each (of 29–30 days). The lunar calendar was connected to an important sidereal event, the observation in the east just before dawn of the dog-star Sirius (personified by the Egyptian goddess Sopdet/Sothis), after it was hidden for a period of 70 days. This was New Year’s Day in the lunar calendar, at the same time of year as the annual Nile inundation. Although the civil calendar was used by the state, the lunar calendar was used for determining the dates of some religious festivals and rituals.

In the Egyptian civil calendar years were not fixed from one set point in history as in our own calendar, but were numbered by the regnal year of the reigning king. When they have survived, dates on documents are given by the regnal year of a king, the number of the month of the season, and the number of the day; for example, “Year 6, month 3 of the season of inundation, day 5 (of King X).” The king’s name is often omitted because it was obvious to the writer and user of the document.

Several king lists that have survived into modern times, as well as Manetho’s History of Egypt, are the basis for converting regnal years of Egyptian kings into years BC. The earliest relevant document is the Palermo Stone, so called because the largest of several fragments of this inscribed stone is now in a museum in Palermo, Sicily. The Palermo Stone was probably carved in the mid-5th Dynasty. It records the semi-mythical and/or unknown Predynastic kings, who cannot be verified from archaeological evidence, as well as kings from the 1st to 5th Dynasties. Beginning in the 4th Dynasty, the years recorded on the Palermo Stone are numbered in relation to a biennial (and sometimes annual) cattle census conducted for purposes of taxation during the reign of each king, not the number of years of a king’s reign, which were not used until late in the Old Kingdom.

Although not very legible, another Old Kingdom king list has been identified on a basalt slab that was recycled to make the lid of the sarcophagus of Queen Ankhenespepy III, a wife of Pepy II. The lid was found at South Saqqara during Gustave Jéquier’s excavations in 1931–1932, but the king list was not recognized until 1993, during a visit to the Cairo Museum by French Egyptologists Michel Baud and Vassil Dobrev. Inscribed on this stone is a king list from the reign of the 6th-Dynasty king Merenra, who preceded his brother Pepy II on the throne.

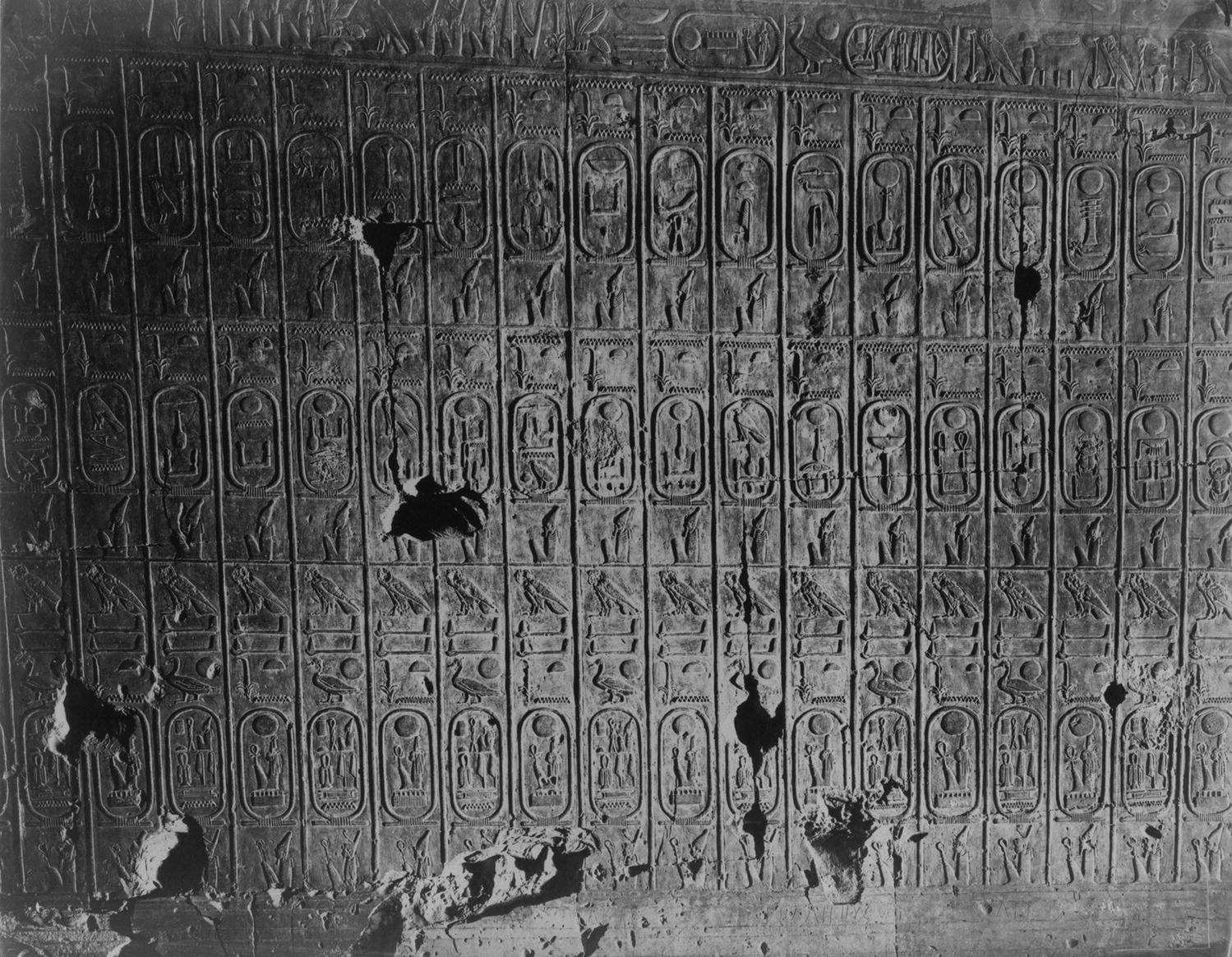

Probably the most important later king list is the Turin Canon, a fragmentary 19th-Dynasty papyrus now in the Egyptian Museum in Turin, Italy. One side of the papyrus records tax receipts, and the king list is on the back, listing kings from the beginning of the Dynastic period (as well as reigns of the gods and “spirits” in a mythical past) through the Second Intermediate Period. Also from the 19th Dynasty is Sety I’s king list carved on his temple at Abydos (Figure 2.5). Many kings of the First and Second Intermediate Periods are absent from Sety I’s list, as are rulers who were considered illegitimate (Queen Hatshepsut, and the late 18th-Dynasty kings of the Amarna Period). Carved on the walls of temples, such king lists should not be considered as a historical record, but as a form of ancestor veneration by the living king, who traced his legitimacy back through a very long line of predecessors.

Figure 2.5 Sety I’s king list from his Abydos temple.

Source: © Griffith Institute, University of Oxford.

Shorter king lists are known in other royal inscriptions, ritual papyri from temples, and some private tomb chapels. Analyses of the king lists along with dated monuments and documents have helped Egyptologists devise chronologies in years BC, but no exact dates before the 26th Dynasty are agreed on by all scholars, hence the variations in published chronologies of pharaonic Egypt. During the Middle and New Kingdoms there were some co-regencies during which a young king ruled for several years with his father, and this practice creates problems for assessing the number of years a king ruled alone. There are also many inherent problems in lists of kings for the intermediate periods as well as discrepancies between the different king lists, compounded by a few kings known from archaeological evidence not being listed at all. In the Late Period and Greco-Roman times Egyptian chronology becomes more accurate, since historical information and/or king lists from kingdoms and empires in Assyria, Babylonia, Achaemenid Persia, Greece, and Rome can be synchronized with Egyptian ones.

Some Egyptian texts also contain information that can be synchronized with astronomical events of known dates, such as the heliacal rising of Sirius, which were mentioned in the Middle and New Kingdoms on documents dated to the year, season, month, and day of a king’s reign. Because the Egyptian civil calendar of 365 days moved one day through the solar year every four years (the so-called “wandering year”), the heliacal rising of Sirius coincided precisely with the beginning of the solar new year once every 1,456 years. This event was recorded as happening in AD 139 during the reign of the Roman emperor Antoninus Pius, and it is possible to work back from that date. In this way, specific datings of astronomical events can be used to calculate exact years BC of the reigns of kings known from king lists. It is uncertain, however, where these astronomical observations were made in Egypt, and year dates vary depending on whether the observation was made in southern or northern Egypt.

Further general corroboration of dates BC is also provided by calibrated radiocarbon dates obtained from organic samples (preferably charcoal) from archaeological sites in Egypt (see Box 4-B). But more exact dating to specific years of a king’s reign can only be obtained through textual evidence when that is available.