MADNESS IN 168

EASY STEPS

Andrew Hackard

The most frequent question I am asked by Munchkin fans is, “How do you come up with all those cards?” (The second-most frequent question is, “Some of the jokes in your game are just awful. Aren’t you ever ashamed?” I love you too, Mom.) In the interest of total transparency, therefore, and on behalf of the entire Munchkin team, let me offer a window into the design process of a new Munchkin game. Our new and wholly fictitious Munchkin game is to be called Munchkin Baroque, a whimsical contest centered around backstabbing, double-dealing, and monster slaying in the blood-drenched world of 17th-century chamber music.

In other words . . . we’ll be Bach!

A PREEMPTIVE DIGRESSION

But, of course, I’ve gotten ahead of myself, so let me back up a moment. Coming up with the theme of a new Munchkin set is rarely as easy as waltzing into a meeting, throwing down the Brandenburg Concerti, and waltzing back out. (For one thing, very few of Bach’s works are in 3/4 time.) Deciding on the next Munchkin game is a discussion often encompassing several conversations over the span of weeks. We ask ourselves such vital questions as:

- Does this have wide appeal, or are we just writing this to amuse ourselves?

- Do we, personally, know enough about the subject to write 168 cards without making unnecessary asses of ourselves?

- Is it inherently funny? If not, can we make it funny?

- Seriously, guys, is anyone going to buy this game?

In this case, let’s assume we’ve asked those questions and are proceeding with Munchkin Baroque anyway. Otherwise, I have to come up with a new example, and I’m already behind deadline.1

FIRST STEPS

Once we’ve decided on a theme, we have to establish the basic features of the set. Most Munchkin games have two possible character traits, such as classes and races or mojos and powers. Deciding what to call the traits is sometimes as simple as, “Let’s just go with classes and races and break for lunch.” Some sets, however, have suffered a more difficult birth, leading to statements like, “If they look like powers and they work like powers, why aren’t we calling them powers? And if we do, we don’t have to write a bunch of new rules and we can break for lunch.”2

We generally have a good idea of how many monsters (of various levels), types of treasures (headgear, armor, and so on), and screwyour-buddy cards (everything else) go into a set. Steve has a skeleton document that he or I can use when we’re just starting to write the cards for a game, so the easy part is done. (Writing 168 jokes? That’s the challenge.) We’ll vary the formula where the needs of a set seem to demand it – or when we feel like it – but most Munchkin sets are pretty much fleshed out from the same skeleton. This is good, because it means that when people buy a new set, it is comforting and familiar and they feel good about giving us their rent money. Also, it saves us a lot of work, and we’re all about that. Too much work, and this will start to feel like a real job.3

COMING UP WITH ALL

THOSE AWFUL JOKES

The mainstay of many elementary school classrooms is the process of brainstorming. This is where everyone gets around a big table, huffs dry-erase markers for a few minutes, and then starts spitting out the dumbest, least practical solutions to whatever intractable problem has stalled work that day.4 No idea is too stupid, implausible, or offensive, and no one is allowed to be critical of anyone else’s harebrained offerings during the brainstorming session. That comes later.

Like many other megacorporations, we at Munchkin Central have implemented brainstorming as a vital part of our development cycle. However, we’ve made a few modifications. First, we’ve done away with that “every idea has value” crap. You cannot expect several people who have been picked for their skill with words, honed on the whetstone of snark, to stay quiet when someone5 suggests Love Handels as a treasure in Munchkin Baroque. We’ve tried, we really have, but keeping your opinion to yourself after someone coughs up a hairball of an idea like that one is tantamount to holding back a sneeze whose time has come – your eyes bug out, your cheeks inflate, and you may as well let it loose, because by that point everyone else knows what you’re thinking and you may hurt yourself if you don’t just share it.

I’ve only been writing Munchkin cards professionally for seven years. Steve’s been doing this since the game launched in 2001. What amazes me, looking at over a decade of Steve’s work, is how consistently he has hit the mark. It makes me very happy when one of my cards makes Steve say, “That joke is awful. I never would have thought of that.” It’s an unusual bit of praise, but our job is far from usual.

One of the most challenging parts of this process is avoiding repetition of a joke we’ve already used (unless we’re doing it on purpose). With over 6,000 Munchkin cards so far, the bottoms of some pretty gnarly barrels have been scraped right through. Each new theme brings a whole new set of pun barrels to tap (Munchkin Baroque, for instance, has a monster called Chopin Tiger, Haydn Dragon6), but we’ve written so many cards now that many of the obvious jokes have already been used, genre tropes be damned. It’s a good thing that the English language is endlessly abusable, for abuse it we do. I thought that I was an expert punster, but working under Steve has made me thoroughly incorrigible. Luckily, Steve is happy to incorrige me. Under his tutelage, I have shed all inhibitions and taste, and it has freed me to write cards that really should be banned under international law.7

With three creative, snarky people (Steve, me, and John Kovalic – more about him later) all involved in the card design process, we’re pretty ruthless about rejecting ideas that are too obscure, trite, or just uninspired. Eventually, we end up with 168 cards that are ready to go to the next circle of Game Design Hell: playtesting.

PLAYTESTING IN PROGRESS:

CHECK YOUR SELF-WORTH AT THE DOOR

The best (worst) jokes in the world can’t save a Munchkin set if it doesn’t work as a game. Playtesting is where, with the assistance of brave volunteers, we discover all the places where we screwed up. It’s a bit like crowdsourced freelance editing, except that people get paid in pizza, not money.8 In the case of Munchkin Baroque, it’s as though Mozart let the orchestra dissect and revise his newest symphony while they’re playing it. Playtesting is nerve-racking, frustrating, disheartening, often maddening, and utterly necessary.

Among the things we ask our playtesters to check are:

- The balance of the various classes (powers, etc.). Do they work together well? If there’s one class that everyone – or no one – wants to play, that tells us we need to adjust them all so they’re more or less equally desirable.

- Same question with our treasures. Some of them are qualitatively better than others, but we usually find ways to balance this out, either by increasing the temptation to sell those cards for levels or by limiting their use so that players have to decide when to pull the trigger on an especially nifty card. Unlike with the classes, however, we want a bit of imbalance. That creates envy, which drives the interpersonal conflict that makes Munchkin so charming.

- High and low points. Are there any cards that stand out as especially good, especially nasty, or especially blah? If playtesters say, “I have no idea why I would ever play this card” (or the opposite: “I would play this card every game if I had it”), that tells us we may need to go back and adjust things. Of course, sometimes we decide the effect is rare enough, or funny enough, that we can leave it alone.

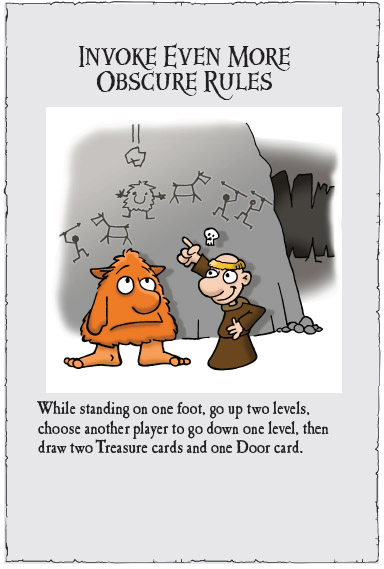

- Clarity. What is confusing or just seems kind of wonky? This open-ended question has led to some of our most insightful playtest comments.9 It turns out that when you give people a chance to tell you what they don’t like, they’re often willing to take it. At great length. For example, in Munchkin Baroque, I had the brilliant idea to create a curse card called “Deaf Composer,” which required the victim to put his fingers in his ears and hum Beethoven until the start of his next turn. This card was, to put it mildly, unpopular. I eventually replaced it with a monster derived from the Ring Cycle: “Siegfried et Roi.” This was also panned, on the specious grounds that Siegfried was German, not French. It’s a hard life, being a game designer.

- Humor. Which jokes were especially funny? Which jokes weren’t? This is one of our checks for obscurity, which we ignore at our own peril. If you see Steve at a convention, ask him about the “Filthy Geats” card. It required a working knowledge of both Beowulf and George Michael, and the insight10 to make the connection. Or, to pick on myself, the card named “Bridle Shower” – obviously, that’s a shady character who shows bridles. The art helps that card, but even so, it’s quite a stretch and makes people read the title twice, which is at least once too often.

Our first group of playtesters is the Munchkin Brain Trust. These loyal fans have proven their dedication to the Munchkin game by offering up thousands of words of opinions (solicited and not) about every published set, and have repeatedly demonstrated their deep insight into the underpinnings of Munchkin and how it is put together. This makes them invaluable to the design process.11 Their work has saved Steve and me from publishing unintentionally stupid rules more times than I want to think about. (“What do you mean, Munchkin Baroque shouldn’t include keytars?”)

The real test of a new Munchkin game, however, comes when we take it out into the public and let them get their cheesy fingerprints all over it.12 When we introduce a game-in-progress to the undifferentiated masses of distracted parents, arrogant teenagers, novice players, and (shudder) rules lawyers, we get suggestions from every type of gamer, all designed to help us make the game better. We also, rarely, get the kind of raw feedback that’s usually reserved for the abyss that is a YouTube comment thread. The first lesson Steve taught me is, “It’s not personal,” and that is a maxim I hold on to when I feel my lip quivering after reading a brutal takedown of some cherished idea.

We credit our playtesters who make useful, helpful comments – or comments that make us laugh so hard that bystanders summon medical attention – so many of them take the time to do a good job. Thanks, playtesters; your assistance is more crucial than you know. Just ignore our tears of blood as you tell us what we did wrong.

IT’S HARD TO MAKE ART

LOOK THIS EASY

Once a new Munchkin game has run the playtesting gauntlet and our wounds have been salved, it’s time to transmute our low-rent playtest cards into the real thing. At this point, we turn matters over to John Kovalic and his talented (if overworked) drawing arm.

It is impossible to overvalue John’s contributions to Munchkin. It’s his art that people see when they pick up a Munchkin box, his art that appears on many of the cards,13 and often his art that takes a middle-of-the-road joke and elevates it to the sublime. (Any failures of sublimation remain the responsibility of the designers; John can’t save every card. He’s a genius, not a superhero.14)

With the benefit of decades of experience, John often knows what works, artistically, far better than we mere wordsmiths. We have learned to listen intently when John explains why our idea for a card illustration is difficult, or even just inferior, because he’s almost always right. The best times, though, are when John takes a pedestrian art spec (short for “specification,” the brief description of what should fill the box marked ART GOES HERE) and gives us a drawing far better than what we had envisioned. My officemates have learned the precise laugh that says, more clearly than words, “John has done it again.”

Even John’s rare mistakes are gifted. We wrote a card a couple of years ago for which we specified a zombie head flying through the air. For some reason, John got fixated on the idea that it was a zombie horse’s head15 and drew it that way. This gave us a really funny piece of art that was not at all what we’d imagined for the card. We didn’t reject the art; we realized that we just had art for which the appropriate text had not yet been written. In this case, the obvious answer was to write a card called “Mister Ded.” As a bonus, that one art suggestion generated two cards. Efficiency!

Writing good specs is an art unto itself, one I am still working to perfect. A regular feature of my workday is a call or email from John in which he identifies a piece of art he’s not sure about or explains why my idea is unworkable. (“Andrew, I know it would be funny to draw the entire cast of Amadeus for Munchkin Baroque, but I only have about three square inches to work with. Can we maybe just do Salieri this time?”) John is patient, kind, erudite, and one of the funniest people I know. He’s pulled our butts out of the fire more times than I care to think about.16

For Munchkin Baroque, we have created a new running art gag: all the characters are wearing white wigs. This may or may not be historically accurate,17 but it does act as a unifying element, a peg for John to hang all his art on. This saves us a bit of time, which is at a premium by this point in the design process. We usually give John about two months to complete a full Munchkin set. This reserves all of us lots of time for collaboration, revisions, and the inevitable “Wait, John, we had a better idea” last-minute emails that are the delight of his existence. To be blunt about it, it’s a miracle he hasn’t stabbed us all with his beloved fine-tip pens by now.

Once the art starts coming in, it goes over to our talented production team for coloring and layout. Fitting too-long text18 onto a small card and leaving enough room to show off the art is a challenge, one they meet brilliantly. They also get to lay out the rules, the box (designing the box is a subject worth its own essay), and any ancillary materials we decide to include. There are close to 200 individual pieces in a Munchkin set, and the production team builds every one of them.

WE’LL FIX IT IN POSTPRODUCTION

Once the layout work is completed, the game goes to prepress for a final set of checks before it goes to print. This is our last opportunity to fix things without spending a whole lot of money, so it’s a critical stage – and one for which we never allot as much time as we really want. As deadlines slide earlier in the process – not an inevitability, but it does tend to happen – you create a comical “must get all the work done now” pileup at the final stages.19 A somewhat startling number of mistakes, both typographical and conceptual, get caught at these final stages (“Did you really mean to include a keytar in a Renaissance orchestra?”), so we dare not stint on it. This can lead to frantic phone calls to our printer that include these words: “I know you said this was a drop-dead date, but what’s the real drop-dead . . . ? Oh.”

Once our prepress checker is satisfied that the set is as good as it’s going to get, everything goes off to the manufacturer. From a design standpoint the game is complete and we just have to wait for it to start appearing on store shelves. Yay, the work is done!

Except, not.

“We’ll fix it in postproduction” is a Hollywood cliché, but sometimes it’s literally true. Computers are complex, and something that looks fine on the screens in our office can turn to gibberish when it’s set for physical production. This final proof stage is our chance to recognize those glitches (usually to a chorus of howls and cursing) and stomp them before they reach print. We don’t always catch everything – every publisher has at least one good story about The Horrid Mistake That Got Printed. I have a few myself, and I’m not about to reveal them here.20

Okay, just one. In Munchkin Baroque, I wrote a monster card called “Dirty Oboes,” which has the poor maligned instruments transformed into vagabonds, never quite sure where they’ll be playing next. I’m not happy with the card, and I’ve talked about some replacement ideas with Steve, but I think maybe I’ll just send it to John and see what he can do with it.

Again.

It’s the Munchkin way: If it ain’t Baroque, don’t fix it.21

Andrew Hackard is the Munchkin czar at Steve Jackson Games. He was also the SJ Games managing editor in a previous lifetime. Andrew has also worked as a math and Latin teacher (not simultaneously), an editor and project manager in educational publishing, and is currently dabbling in professional lassitude and ennui. When not working on Munchkin, Andrew can be found curled up on the couch, trying to silence the punsters in his head. It doesn’t work. Andrew lives in Round Rock, Texas.