MONTY HAUL AND

HIS FRIENDS AT PLAY

David M. Ewalt

I was 10 years old when I tried my first roleplaying game – too young, perhaps, to understand the nuances of a game as complex as Advanced Dungeons & Dragons. But what I lacked in maturity, I made up for with intellectual arrogance. I threw myself into the pastime, and within months of discovering it, considered myself an expert. I knew all the rulebooks by heart and could twist them to my will; any time a game master dared to tell me what my character could or could not do, I’d slap him down with a perfectly quoted rule or some obscure bit of arcana. I thought I was the master, and I had a pile of badass, high-level characters to prove it.

I still have all of my character sheets from those days, carefully preserved and carried from home to home over three decades, as a jock might hang onto his favorite cleats or lucky baseball bat. But when I look at them now, I don’t see evidence of game mastery. Consider “Sir Howland, The Wolf Knight,” a 15th-level ranger: Nearly all his ability scores are maxed, he wears +4 plate armor, carries a +4 shield, and is armed with a +6 vorpal sword, a +4 dagger, and a +5 lance. His special abilities are listed on one corner of the sheet in my messy adolescent handwriting: Incredible senses, great speed, immune to disease, detect evil, summon ethereal sword, black belt in karate and ninjitsu, use technology, time/dimension travel.

My name is David, and I am a recovering munchkin.

I refer, of course, not to the short-of-stature citizens of Oz in L. Frank Baum’s 1900 novel, nor (yet) to the Steve Jackson card game of a century later. I was a munchkin of the mid-1980s variety: a kid who turned a friendly, cooperative roleplaying game into a scramble to exploit the rules, get the most loot, and become the most powerful player at the table – whether or not anyone else had any fun.

The first use of munchkin in this pejorative context probably didn’t occur during a session of D&D, but in one of the historical wargames that gave birth to fantasy roleplaying. Wargames evolved out of board-games like chess, over time becoming increasingly complex simulations of battle. Instead of a king, a queen, and a couple of knights, each player might have hundreds of pieces on the table, ranging from halberdiers to cavalry to cannons. These games were played both as competitive entertainment and as a violence-free simulator of real blood-and-guts war. In the 1860s, the German statesman Otto von Bismarck made a wargame called Kriegsspiel part of the standard training regimen for military officers, and historians still cite the game as a contributing factor in decades of Prussian Army victories.

Wargames made their way to the United States in the early 20th century, often carried in the packs of veterans of the two world wars. For decades, the fan base for Kriegsspiel and its kin was dominated by men who called themselves “grognards” – a French term for old soldiers. They were a proudly erudite and often crusty lot, obsessed with the minutiae of their favorite game’s rules and with military history. When a group of grognards sat down at the game table, the goal was to accurately simulate real-world battles; creativity was often frowned upon, and fun was welcome but not required.

It’s no surprise, then, that some members of the community bristled when their pastime began to go mainstream. In 1952, an Army veteran named Charles S. Roberts created a game called Tactics that simplified complex historical wargames such as Kriegsspiel into a mass-market boardgame. He followed it up in 1958 with an equally accessible Civil War simulation called Gettysburg, and by 1962 Roberts’ Avalon Hill Game Company was one of the biggest boardgame publishers in the United States.

Tactics and Gettysburg introduced a new type of game to children around the country, and that meant the traditionally gray-haired ranks of local wargaming clubs began to fill up with new, younger members. The crustier grognards began to refer to these upstart players as “munchkins” – a mild slight meant to indicate a young, inexperienced player.

The tension between new and old gamers intensified in the early 1970s, when the munchkins started moving wargaming away from its traditional historical roots. Young, mostly college-aged players introduced elements of fantasy to their simulations, like druid priests using magic to fight Roman armies, instead of swords and spears. Soon they began to play as individual warriors, instead of controlling entire armies – and fantasy roleplaying was born.

The first and most famous of these fantasy roleplaying games (RPGs) was TSR Hobbies’ Dungeons & Dragons, but there were many others. All of them appealed to gamers because they encouraged creativity and allowed the participants to build vivid imaginary characters and fantasy worlds. But they were still based on rules, and that opened the door for a certain kind of person to subvert the games’ intent.

Sometimes the problem was the players – usually young munchkins like me, who focused on exploiting the rules and making their characters more powerful. At other times, it was the fault of the person running the game – inexperienced game masters who made things too easy for their players, buying their affection with constant rewards of gold, magic items, and experience. These incompetent authorities soon earned their own derogatory nickname; they were “Monty Haul” referees, a reference to Monty Hall, the famously generous host of the TV game show Let’s Make a Deal.

At first, RPG designers tried to combat the munchkins by adding more rules to their games, in the hopes that no one would be able to keep track of and exploit them all. In the foreword of Eldritch Wizardry, a D&D supplement published in 1976, editor Tim Kask wrote that the book “should go a long way towards putting back in some of the mystery, uncertainty and danger . . . no more will some foolhardy adventurer run down into a dungeon, find something and immediately know how it works.”

It didn’t achieve that goal, of course. So the next D&D supplement, Gods, Demi-Gods & Heroes, added mythological deities such as Zeus and Osiris to the game, in an attempt to cap the progression of high-level munchkin characters: “Perhaps now some of the ‘giveaway’ campaigns will look as foolish as they truly are,” Kask wrote in the foreword. “When Odin, the All-Father has only 300 hit points, who can take a 44th level Lord seriously?”

The munchkins could, that’s who, and their numbers were only increasing.

In July 1977, TSR published the Dungeons & Dragons Basic Set, a simplified edition designed for people unfamiliar with wargames. Priced inexpensively and sold in toy stores, the Basic Set brought fantasy roleplaying to the masses. That meant more kids in the hobby. When Advanced Dungeons & Dragons was introduced later that year, it made the problem worse: Basic focused on low-level characters, but AD&D was designed for higher-level play. It was comprehensive and complex – like crack for munchkins and Monty Haulers.

In the May 1978 issue of the roleplaying magazine The Dragon, game designer James Ward lampooned these problem players in an article titled “Monty Haul and His Friends at Play.” It’s a short story that imagines a group of gamers who keep one-upping each other with ever-more powerful and ridiculous characters: iron golems, knights who ride platinum dragons, and even Martians armed with radiation rifles.

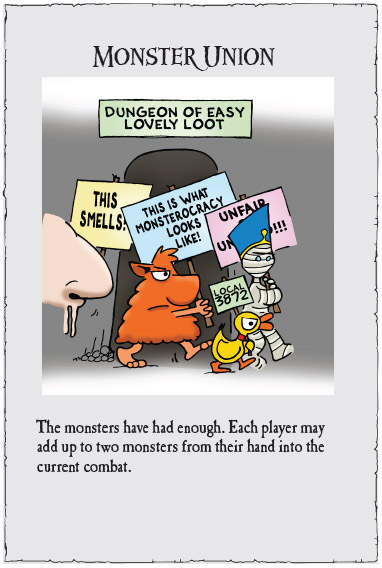

This behavior – both from players and game designers trying to counter it – is ridiculous, of course, and that’s the point of Steve Jackson Games’ Munchkin. At its heart, the beloved card game is an extended riff on those roleplaying fans who engage in the folly of power gaming, the immature competitors who play only to win. We’re in on the joke because these “shrieking geeks” are found across the roleplaying landscape, from D&D to Pathfinder to GURPS. We all know them – and all too frequently we are them.

Munchkin skewers the behavior of its eponymous subjects with pinpoint accuracy and razor wit. The “Invoke Obscure Rules” card mocks the favorite battle tactic of every desperate nerd that memorized the source books: “No, he didn’t hit me, because the Wilderness Survival Guide says characters suffer a minus one penalty to attack at night when the only illumination is moonlight.” If that doesn’t work, they might resort to a “Convenient Addition Error” on an armor class of 12 with a +1 to dodge: “No, he didn’t hit me. He needed a fourteen.” When all that fails, these players fall back on the ultimate munchkin tactic: “Whine at the GM.”

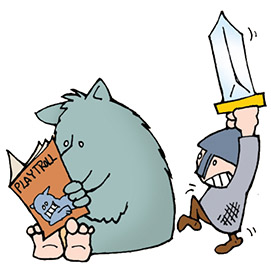

The monster cards reference classic fantasy roleplaying game creatures, too. The “Floating Nose” mocks the beholder, a giant levitating eye. The “Gelatinous Octahedron” riffs on the gelatinous cube, which lurks in dungeons and dissolves unwary adventurers in its acidic jelly. And the “Platycore” lampoons part-thispart-that monsters like the hippogriff, manticore, and owlbear. (Of course, in the age of Harry Potter, you don’t have to be an RPG geek to get a hippogriff gag; like so many other fantasy icons, the hybrid horse/eagle has gone mainstream.)

A Munchkin deck can actually double nicely as a storehouse of roleplaying game history. The “Really Impressive Title” +3 bonus treasure card hearkens back to the short-lived phenomenon of experience-based honorifics: in first-edition AD&D, a third-level druid was an “Initiate of the 1st Circle” and a sixth-level thief was a “Filcher.” One of my favorite cards, the level 8 “Gazebo” monster, references a classic story told by game designer Richard Aronson about a player he knew who considered every angle and option before acting, but still missed the point entirely. Aronson’s version of the story goes something like this:

Eric the paladin was traveling across the estate of a rich lord when the game master told him, “You see a well-groomed garden. In the middle, on a small hill, you see a gazebo.”

The word was unfamiliar to Eric, so he decided to proceed with caution. He drew his sword and cast the spell Detect Good upon the gazebo.

“It’s not good, Eric,” said the game master. “It’s a gazebo.”

“I call out to it,” Eric said.

“It doesn’t say anything. It’s a gazebo.”

Eric put away his sword, readied his bow, and nocked an arrow. “Does the gazebo respond?” he asked. It didn’t.

“I shoot it with my bow. What happens?”

The game master sighed. “There is now a gazebo with an arrow sticking out of it.”

“Did I wound it?” Eric asked.

“No, Eric! It’s a gazebo!”

“But that was a plus-three arrow!”

Unable to damage, intimidate, or in any way harm the strange “beast,” Eric eventually decided to run away. But by that time, the frustrated GM had experienced all he could take of the paladin’s obtuse behavior.

“It’s too late,” the GM snarled. “You’ve awakened the gazebo. It catches you and eats you.”

Munchkin succeeds as a game because it is well designed and funny, but it has become a classic because it is so richly steeped in these stories and references. It’s the ultimate in-joke, told by two game designers who know and love roleplaying geek culture, because they are roleplaying geeks, too.

Steve Jackson has been writing and publishing roleplaying games since the early days of the hobby, including one of the very first “funny” RPGs, 1984’s Toon, which was designed by Greg Costikyan and developed by Warren Spector. Players take the roles of cartoon characters and are encouraged to break the rules and subvert the conventions of roleplaying games as much as possible; the players’ goal is to make one another laugh.

“Back when I was roleplaying regularly, most, though not all, of my groups enjoyed being silly and poking fun at the conventions of the game,” Jackson says. “In my very first continuing roleplaying campaign, one of the characters was a dwarf who mounted a chicken on the end of a long pole and carried it in front of him to lure the slimes down from the ceiling. He had to change the chicken regularly, of course, so he carried a supply with him.”

Another Steve Jackson publication, 1986’s Generic Universal Role-Playing System, or GURPS, is a classic system that encourages players to experiment with different settings. There’s GURPS Horror and GURPS Espionage and GURPS Old West. This desire to leap genres is characteristic of Jackson’s work; we see it again in Munchkin expansions such as Munchkin Cthulhu, Munchkin Impossible, and The Good, the Bad, and the Munchkin.

Combine a deep familiarity with gamer culture with a willingness to have fun with its conventions, and it’s no mystery why Jackson went on to create a card game like Munchkin. “My own taste in humor has always leaned toward parody and absurdity, so the whole Munchkin thing just clicked,” he says. “It’s easier to mock what I know.”

Munchkin illustrator John Kovalic has a background in roleplaying games, too. He grew up in England in the 1970s, and during a family trip to London, made a fateful stop at the Games Workshop store on Bolingbroke Road. “They had all these little four-page, photocopied pamphlets about what roleplaying is and how you roleplay,” he told me. “I had never seen anything like it before, and it just absolutely set my imagination on fire. So I bought these little books and went back to my school in Somerset and formed a roleplaying group, just as thousands if not millions of kids have done since.”

The young gamer went on to become a professional cartoonist, and when Steve Jackson asked him to illustrate Munchkin, he jumped at the opportunity. “I was just thrilled, absolutely beside myself, because I had been playing Steve’s games since the late 1970s,” he says. The subject matter resonated with Kovalic, too: “I was very familiar with the kind of game Munchkin was describing,” he says. “I have had most of those things happen to me in my own gaming sessions.”

Kovalic notes that some of his favorite Munchkin cards aren’t the ones with the most obscure roleplaying game references, but the ones where he’s still proud of the illustration – like the “Duck of Doom” and “Spiky Knees.” And as much as I revel in RPG arcana, I tend to agree with him. My top cards are the ones that boast great drawings, like “Chicken on Your Head” and “Net Troll,” and the corniest jokes, like “Broad Sword,” “Pukachu,” and “Wight Brothers.”

Still, I do love it when a card describes something so familiar it seems ripped straight out of my most recent tabletop roleplaying session. And I love that those references aren’t as hard to understand as they used to be. Like Harry Potter and his hippogriff, the RPG nerd is flying high: video games are a $70 billion global business, The Lord of the Rings is the highest-grossing film trilogy in history, and they play D&D on prime-time network TV. When Community and The Big Bang Theory can build entire episodes around fantasy RPGs, you know they’ve gone mainstream.

That’s good news for those of us who love roleplaying games. As the pastime enters its fifth decade, the future looks bright; with more people sharing our interests than ever, we may well be entering a golden age for fantasy gaming. Who knows what great games we’ll play?

We’ll dream of new adventures, of brave heroes that overcome great odds to save the day . . . of treasure and magic items, of piles of gold and silver . . . of great fame and greater power . . . of destroying our enemies and conquering their land . . . of ruling with an iron fist, becoming stronger and stronger – stronger than anyone who has ever lived, until we conquer death itself and travel all the planes of existence . . . of dethroning the gods themselves, and standing triumphant at the center of all of creation, of becoming the ultimate power, the beginning and the end. . . .

Or maybe that’s just me. Once a munchkin, always a munchkin.

David M. Ewalt is an award-winning journalist and an authority on the intersection of games and technology. He is the author of the book Of Dice and Men: The Story of Dungeons & Dragons and The People Who Play It, which chronicles the history of D&D’s origins and the game’s impact on business and culture. Find out more at davidmewalt.com.