INTRODUCTION

THE SPACE BETWEEN THE CARDS

James Lowder

It was Dave Arneson who got me to play Munchkin for the first time. As the gaming history aficionados among you may already know, Dave co-created Dungeons & Dragons. He was also a nice guy who loved games – not just designing them, but playing them and sharing his enthusiasm for them. So in 2006, when I was putting together a roster of industry notables I hoped would contribute to an essay anthology about the best hobby games, Dave’s name appeared near the top of the list. In fact, the book as I’d envisioned it would have a lot in common with the conversations about games I’d had with Dave the few times our paths crossed at conventions, though probably with fewer jokes about our mutual former employer, TSR.

Dave responded to my invitation by rattling off a few games he’d gladly champion. His selections were characteristically diverse and demonstrated how current he’d been keeping on the hobby. For every classic he mentioned, like M. A. R. Barker’s Empire of the Petal Throne, he listed several newer designs, such as Carcassonne and HeroClix. He finally settled on a title less than a year old at the time of our conversation: Dirk Henn’s excellent resource management game, Shogun.

Sadly, that essay never saw completion. First Dave’s teaching schedule, then his failing health precluded him from ever finishing his contribution to Hobby Games: The 100 Best, but the book’s subject clearly inspired him. Even after he’d settled on his topic, I received several short emails in which he suggested more titles he thought belonged on that list of the 100 best, games he hoped some other essayist would cover. I shared Dave’s zeal for most of the designs he mentioned. When the subject of Munchkin came up, though, I politely demurred.

“I’ll bet you haven’t played it much,” Dave noted – quite accurately, as it turned out.

Oh, I was aware of Munchkin from the moment designer Steve Jackson and artist John Kovalic unleashed it upon the world in 2001. It would have been impossible for me to miss its debut. I was working extensively in the hobby game market at the time, and Munchkin’s launch was a noteworthy event in that little corner of the publishing industry. The core set recorded very strong initial sales and, more importantly, inspired a vocal fan base, the beginnings of what would become a veritable crusading army of players eager to spread the word of Munchkin’s glories. The core set subsequently went on to capture the Origins Award that year for Best Traditional Card Game, a critical affirmation to go along with all the popular success. So it was pretty clear to everyone paying the least bit of attention that Steve Jackson Games had hit upon something big.

Given the creators involved, I should have been one of Munchkin’s early adopters. Steve Jackson’s designs hold a prominent place in my gaming history. I got into the hobby in the late 1970s through roleplaying games such as Dungeons & Dragons and Villains and Vigilantes, and relatively obscure board games such as Eon’s Cosmic Encounter, but early in my gaming life I also faced annihilation beneath the treads of a gigantic robot tank in Steve’s wargame Ogre, vied for secret control of the world through his card game Illuminati, and blasted my way across the post-apocalyptic future in the classic vehicular combat game Car Wars, which Steve designed with Chad Irby. Later, I became a fan of SJ Games’ roleplaying system, GURPS, and its wonderfully researched supplements, which covered topics as wildly diverse as Imperial Rome and the paranoid cult TV series The Prisoner, Miskatonic University and the Scarlet Pimpernel. Shortly before Munchkin’s release, Steve even hired me to serve as editorial ringmaster for a book of RPG villains dreamed up by GURPS fans.

My admiration for artist John Kovalic’s work runs just as deep. I’ve been an avid follower of his comic strip Dork Tower, which chronicles the lives and loves of a cadre of gamers in the fictional town of Mud Bay, Wisconsin, since shortly after its debut. In the late 1990s, it started popping up in a few of the hobby-themed magazines for which I occasionally wrote; before I knew it, Dork Tower was my first destination when opening up a new issue of Dragon or Shadis. I’ve faithfully followed the strip since then, as John transitioned it first to comic book form, then to a webcomic. And there are his stealth projects, like providing the charming apple illustrations for the best-selling game Apples to Apples. You can also stumble across John’s work outside of gaming in such little-read markets as The New York Times and Rolling Stone.

So I should have been an easy sell for a fantasy gaming-themed card game by Jackson and Kovalic, right? I wasn’t, though.

Looking back, it’s difficult for me to pin down exactly what stopped me from picking up Munchkin at my local hobby shop. I sometimes find screw-your-neighbor designs frustrating. I also recall feeling a bit overwhelmed by the number of supplements and new base sets that followed hard on the heels of the core game’s release; it’s always a challenge to sort out which add-ons are necessary to fully enjoy a game once a series really begins to take off. There was Munchkin’s theme, too. I spent the first few years of my publishing career working on, among other things, the Forgotten Realms, a setting often criticized by narrative-focused hobbyists as a haven for power-gaming munchkins. I couldn’t imagine a way to make the generally painful “right way to play an RPG” debate entertaining, even as a spoof.

The art was the first thing that struck me when, prompted by Dave Arneson’s insightful observation, I finally bought and unboxed Munchkin. John’s drawings were charming, as expected, and packed with knowing nods to gaming culture. (Essays in this collection reference the story behind the “Gazebo” monster card, for example.) The illustrations were also narratively evocative, to borrow a phrase from academia. That means there’s a story implied in such cards as “Pretty Balloons,” “Sleep Potion,” and “Out to Lunch,” events that led to the moments of conflict they capture – or the inevitably bad consequences of those frozen actions. The curse cards are especially rich in suggested story. I don’t know about you, but I’d like to hear the tale that resulted in that chicken perching on the head of the justifiably annoyed Thief, or the sequel, where he freed himself from the poultry pompadour.

As I looked a little deeper, Steve’s text did its part to keep the mood light, even while fleshing out the game’s setting. Professional courtesy, we learn, prevents Lawyers from attacking a Thief, though they’re more than happy to slap anyone else with an injunction that allows all the other munchkins at the table to rob them of a card. Many times the text cuts right to the point, but in a way that begged for a more detailed explanation. “You should know better than to pick up a duck in a dungeon,” munchkins and their minders are admonished when the “Duck of Doom” curse card comes into play. As with the head-sitting chicken, players surely wonder about the ducks that apparently roam the Munchkin dungeons in great numbers, punishing anyone who foolishly handles them.

As for the game itself, conflict is central to Munchkin, to be certain, but the text and the art both frame that conflict in such a funny, friendly way that players must laugh their way through it. As I noted earlier, I’m not a huge fan of screw-your-neighbor designs. My wife is downright opposed to them. (Kind person that she is, she would have more fun with the tile-laying game Carcassonne if it were an exercise in cooperative map-building, not a contest where players occasionally direct a river into the courtyard of a rival’s unfinished keep.) Yet she and I and our teenaged son can all agree on Munchkin when family night rolls around, and we play it with only good-natured clashes.

That’s an impressive feat Munchkin pulls off there.

The secret is in the design. Each new base set takes a genre and captures its essence. Steve and John and Munchkin czar Andrew Hackard toss all of the genre’s notable examples into the hopper and distill them down to a set of tropes and trappings that can be rendered in miniature, on 33⁄8" by 21⁄4" cards. On their own, the cards can be delightful and amusing, but their real power becomes apparent during play. They shape the story being told around the gaming table by providing touchstones that cheerfully remind the players of the genre’s greatest hits. The cards identify the central and smile-worthy elements of a zombie yarn or fantasy dungeon crawl or martial arts epic, depending upon what flavor of Munchkin you’ve selected.

It’s the players who connect those fragments. Their laughter and their frantic negotiations and, yes, even their conflict fill the spaces between the cards. Their play sweeps up all the disparate tropes and characters and bits of setting and gives them life as part of a new unified tale. The exact composition of that tale – the nature of the heroes involved and the way the combat goes down, whether the Tuba of Charm works its magic as intended or a curse strips the munchkin of that fabled instrument at just the wrong time – depends upon the assembled players. Everyone brings a different perspective to the table, after all. Given that and the endless combinations of available cards, no two Munchkin sessions are ever going to be exactly the same.

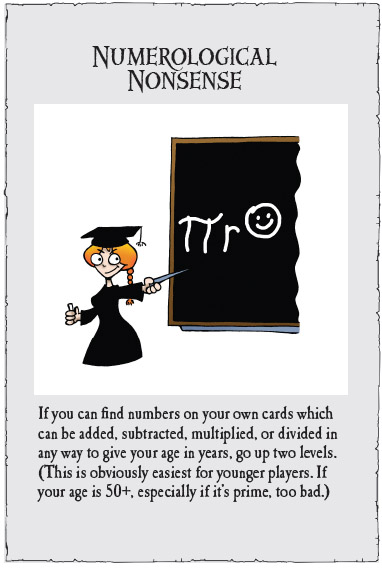

We tried for the same sort of diversity with the essays in this collection. They’ve been penned by people who know Munchkin from the inside, as designers and artists and editors, and by others who adore it as players and enthusiasts. The essays offer glimpses into the process by which Munchkin games and associated cool stuff are created, the comedy theory behind its success, even what Munchkin can teach us about that old “right way to play an RPG” debate (in ways we hope are both entertaining and enlightening). Some of the material is serious, much of it whimsical. Even if you’re a diehard fan, you should gain some new insights into Munchkin here, in addition to adding some nifty new rules to your gameplay arsenal.

Hey, it wouldn’t really be a Munchkin product if it didn’t come with playable rules.

That’s been a given pretty much from the moment I first discussed this project with the teams at BenBella and Steve Jackson Games. New rules were something everyone wanted to see, and the boffins over at SJ Games did a bang-up job creating them, drawing their inspiration directly from each essay’s content. John Kovalic somehow found room in his insanely busy schedule to create original art for the game rules, too. All told, this makes The Munchkin Book a part of the game as well as a commentary about the game.

If we got any more meta, the book might vanish into a self-referential paradox and take us all with it.

Instead, we’ll invite you to put down that Hammer of Kneecapping and Cheese Grater of Peace, settle back on that whopping great treasure Hoard with a flute of Yuppie Water, and let us share some interesting and amusing things about Munchkin. If you were bright enough to get to the party early, we salute your obviously superior judgment. If you’re a relative newcomer, great to see you, too. We’re happy it didn’t take Squidzilla’s tentackly grasp (or the understated goading of a game design legend) to get you here.

And if you’re paging through this book in the hope it might provide some clue as to why Munchkin seems to be popping up everywhere you go, from hobby stores and comic book shops to mega-chain retailers, we’re betting that the collective enthusiasm contained within these pages will make you want to give it a try. Don’t worry about coming in late. There are always more monsters to kill, more treasure to be stolen, and more buddies to be stabbed – and a whole lot of fun to be had while doing it.

James Lowder has directed lines or series for both large and small publishing houses and has helmed more than a dozen critically acclaimed anthologies, including Madness on the Orient Express, Curse of the Full Moon, and the Smart Pop collections Triumph of The Walking Dead and Beyond the Wall. As a writer, his credits include the best-selling, widely translated dark fantasy novels Prince of Lies and Knight of the Black Rose, short fiction for such anthologies as Shadows over Baker Street and Genius Loci, and comic book scripts for Image, DC, and Desperado. He’s written hundreds of reviews and essays for publications ranging from Amazing Stories and The New England Journal of History to BenBella’s King Kong is Back! and The Unauthorized X-Men. His work has received five Origins Awards and an ENnie Award, and been a finalist for the International Horror Guild Award and the Stoker Award. He’s just the sort of person who would pick up a duck found wandering a dungeon, consequences be damned.