CHAPTER THREE:

THE MISSIONARIES

These people who came west to “civilize” the heathen—what made them decide to do that? To me it’s completely irrational to go into somebody else’s country and try to tell them how to think, how to pray, how to live, how to raise their children.

—Roberta Conner, director, Tamástslikt Cultural Institute

Marcus and Narcissa Whitman and most of their fellow missionaries came from an area of western New York widely known as the Burned-over District because of the waves of evangelistic fervor that swept over it in the nineteenth century. The phrase was attributed to Charles G. Finney, a Connecticut-born preacher who pioneered the kind of religious revivals that became commonplace in the region during the 1820s and 1830s. The revivals were characterized by fiery sermons, public confessions of sin, weeping, praying, and collective conversions. Some lasted for weeks—to the point, it was said, that there was little “fuel” (unsaved souls) left to “burn” (convert to Christianity). These events particularly enthralled Narcissa, but both she and Marcus had what is known as a conversion experience during a revival, as did Henry and Eliza Spalding. All four of them embraced the “Great Commission”—a biblical mandate to “go ye into all the world, and preach the gospel to every creature”—a standard exhortation from the revivalist pulpit.

The upsurge in evangelism coincided with an accelerated movement of Euro-Americans westward. In 1830 the United States was still a small country, consisting of only twenty-four states (all but two of them east of the Mississippi River), and the borders with British Canada and Mexico were in dispute. But there were those who believed it was the nation’s “manifest destiny” to colonize all the land from coast to coast, as far north as the fifty-fourth parallel and deep into Mexican territory to the south. That the land was already occupied, and had been for thousands of years, was not a deterrent. Estimates of the indigenous population then living within what is now the continental United States vary wildly and amount to little more than guesses. Lewis Cass, secretary of war under President Andrew Jackson from 1831 to 1836, used the number 313,130 (including 105,060 Indians east of the Mississippi and another 208,070 to the west). Other calculations ranged from 472,000 to nearly 600,000 total. Not in dispute was the fact that the population had been decimated since the arrival of non-Indians. “That the Indians have diminished, and are diminishing, is known to all who have directed their attention to the subject,” wrote Cass, a central figure in the implementation of the Indian Removal Act. The law, signed by Jackson in 1830, authorized the president to negotiate treaties with eastern tribes to relocate them west of the Mississippi, outside the existing borders of the United States. “And these are the remnants of the primitive people, who only two centuries ago, possessed this vast country; who found in the sea, the lakes, the rivers, and forests, means of subsistence sufficient for their wants,” Cass added.1

Cass was among those who defended the Indian Removal Act as a benevolent measure. By forcing Indians to move away from areas of white settlement, he argued, the government could ensure that at least some “remnants” of the population would survive. Otherwise, they would be doomed to extinction. George Catlin, a Pennsylvania-born artist who spent years painting Indians of the Great Plains, went a step further. He called for the creation of a sort of theme park—a vast western preserve where Indians could live in unmolested harmony with nature, and tourists could stop by to view the quaint ways of the “specimens.” Catlin seized upon this idea during a trip to the Dakotas in 1832 and continued to refine it as he traveled around the Plains throughout the decade, painting Indians and collecting artifacts. He presented a fully articulated vision in his 1841 masterwork, Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs and Condition of the North American Indians. He imagined “a magnificent park, where the world could see for ages to come, the native Indian in his classic attire, galloping his wild horse, with sinewy bow, and shield and lance, amid the fleeting herds of elks and buffaloes.” It would be “a nation’s Park, containing man and beast, in all the wild and freshness of their nature’s beauty!”2

Catlin was a sentimentalist, full of romanticized regrets about the dismal prospects facing the “children of the forest.”3 Evangelicals like the Whitmans and their associates were determined to save Indian souls and believed the best way to do that was to strip them of every vestige of their traditional way of life. They were convinced that if Indians were to survive in a country increasingly dominated by whites, and eventually enjoy a satisfactory afterlife, they had to live like white people: learn English, cut their hair, wear European clothing, become farmers, and convert to Christianity. “We point them with one hand to the Lamb of God,” Henry Spalding wrote, “and with the other to the hoe.”4

Three prevailing principles guided the missionaries: that Christianity equaled civilization and vice versa; that “the dear heathen” were living in a savage and degraded state because they did not know God; and before the Indians could fully know God, they needed to embrace white culture. Eliza Spalding wrote about her eagerness to bring “the blessings of civilization and religion” to Indians.5 Henry Spalding insisted: “The only thing that can save them from annihilation is the introduction of civilization.”6 Few Euro-Americans at the time would have questioned the assumption that Christianity was the basis for “civilization.” As historian Elliott West has observed, “religious conversion and cultural transformation were parts of one process, fully entangled.”7 The two objectives fed each other. The initial impulse that motivated these missionaries was evangelistic. They were idealists who deeply believed that the unsaved would spend eternity in the fires of hell if they were not converted to Christianity. But over time, they became unapologetic agents of what some scholars today call “settler colonialism.” Marcus Whitman put it bluntly in an 1844 letter to relatives in New York: “I have no doubt our greatest work is to be to aid the white settlement of this country and help to found its religious institutions.”8

People who knew Marcus Whitman said he looked something like his brothers and nephews. In photos, the faces of these men are characterized by sharp cheekbones, overhanging eyebrows, thin lips, downturned mouths, and large, angular noses. None of them bear any resemblance to the hunky figure memorialized in bronze and representing Washington State in the US Capitol’s National Statuary Hall. Some acquaintances said that Whitman was tall; others that he was of medium height. Some remembered his eyes as blue; others, gray. There was general agreement that he was lean (“raw boned,” by one account), with slightly stooped posture.9 He suffered frequent bouts of ill health; his initial application to become a missionary in 1834 was rejected because he was considered too frail. He occasionally wore leather “pantaloons” when riding horseback in Oregon Country, but he would have been appalled to be portrayed in buckskins—a material he associated with “heathen” culture. He preferred to dress in the woolen coats and trousers favored by the professional men of his era. An inventory of his clothing after his death included a “superfine” coat valued at $45 ($1,250 in 2020 dollars) and a “silk velvet vest” valued at $8 ($222). His total wardrobe was worth more than $325 (nearly $10,000)—making him considerably better dressed than the frontiersman on the pedestal in Statuary Hall.10

Paul Kane created these small pencil sketches sometime during his two-year odyssey to document indigenous life in the Northwest in the 1840s. He never identified the subjects, but in 1968, an amateur historian and Whitman enthusiast in New York argued that they could have been Marcus and Narcissa Whitman. Used with permission of the Royal Ontario Museum © ROM; 946.15.293 and 946.15.299.

Marcus Whitman was born in a log cabin in Federal Hollow (later renamed Rushville), in the Finger Lakes region of upstate New York, on September 4, 1802, the third of Beza and Alice Green Whitman’s six children. Federal Hollow, located on land that had once been farmed by Seneca Indians, had been chartered as a town just a few years earlier. Beza, a shoemaker and tanner, and Alice, both natives of western Massachusetts, moved to the settlement in the fall of 1800. Beza built the town’s first tannery, producing the leather that he used in his shoemaking business. He was prosperous enough to move his growing family from the log cabin into a large frame house five years later. The family lived in only part of the house; the rest of the building was used as an inn and tavern. Alice managed the tavern and also helped out in the little shop, opposite the house, where Beza made shoes.

Growing up in rustic conditions in a newly settled village, Marcus acquired skills in self-sufficiency that would serve him well on the western frontier. He chopped wood, tended animals, learned basic carpentry, and helped his parents with other chores. “I was accustomed to tend a carding machine when I was a boy,” he recalled in a letter written in 1846, referring to a device used to prepare wool for spinning.11 As historian Clifford Drury has pointed out, Whitman rarely reflected on his past. Of his 175 surviving letters, this was the only one to mention an experience in early boyhood. That reticence might be partly explained by the emotionally challenging circumstances of his later childhood.

Beza Whitman died on April 7, 1810, at age thirty-seven, leaving Alice with five children under age twelve. A few months later she sent Marcus, then eight, to live with his grandfather, Samuel Whitman, and uncle, Freedom Whitman, in the village of Cummington, in western Massachusetts. Alice, according to one of her grandchildren, “never spent any time in sentiment.”12 The boy’s new guardians were devout Baptists. Marcus described them as “pious” men who “gave me constant religious instruction and care.”13 He lived with these relatives for five years. He was thirteen when he returned to Federal Hollow for the first time since leaving home, arriving at the family house unexpectedly around twilight and knocking on the door. No one recognized Marcus, including his mother. He was a total stranger to his seven-year-old sister, also named Alice, who had been only two years old when he left. As his sister told the story to her own daughter many years later, when Marcus saw his mother, he said, “How do you do, Mother?” She replied, “I’m no mother to you,” and he burst into tears.14

During her son’s absence, Marcus’s mother had remarried and given birth to two more children. Her new husband, Calvin Loomis, had taken over Beza’s businesses: the tannery, the shoe shop, and the tavern. Marcus stayed only about three weeks before returning to Massachusetts. His grandfather arranged for him to live with a family in Plainfield, near Cummington, where Marcus attended a school taught by the pastor of the local Congregational church. Among his fellow students was the abolitionist John Brown. During this period Marcus embraced the Calvinistic theology that would govern the rest of his life.

At age seventeen Marcus had a conversion experience. “I was awakened to a sense of my sin and danger and brought by Divine grace to rely on the Lord Jesus for pardon and salvation,” he wrote, in words typical of other “converts” in the Burned-over District.15 He wanted to become a minister. However, both the Congregational and the related Presbyterian denominations required that their ministers be well-educated, with four years of college and at least two years in a theological seminary before they could be ordained. Six years of schooling would be expensive, and Whitman’s family could give him little, if any, financial help. In addition, his mother, who was not particularly devout and never joined a church, was not sympathetic to his ministerial ambitions. He would later chastise her for insufficient piety.16

When he was eighteen, Whitman moved back to his hometown (which by then had been renamed Rushville). He lived in his mother’s house and worked in his stepfather’s tannery and shoe shop until he “attained his majority” (in the terminology of the day) on his twenty-first birthday. At that point, Whitman apprenticed himself to a local doctor—the first step toward becoming a physician. In contrast to the lengthy training needed to become an ordained minister, a license to practice medicine could be obtained after only two years of “riding” with a doctor and a sixteen-week session at a medical school.

Whitman completed his apprenticeship and enrolled for the fall term at the College of Physicians and Surgeons in Fairfield, New York, in 1825. His education there consisted mostly of reading textbooks and listening to lectures. There were virtually no laboratory facilities and no hospital or clinic nearby where students could gain hands-on experience. Cultural taboos restricted the use of human bodies for dissection. Under a law passed by the New York State Legislature in 1820, unclaimed bodies of convicts who had died in the Auburn State Prison could be given to Fairfield College for dissection, but it was still rare for students to have legal access to a cadaver. Anatomy, like other subjects in the medical school, was taught mostly by lectures. Whitman finished his term on January 23, 1826, and received a medical license the following May. He had not yet earned the right to put MD behind his name: the doctor of medicine degree required a second sixteen-week course at a medical school. He would return to Fairfield for a second term in 1831. Meanwhile, he temporarily took over a medical practice in Pennsylvania for a former classmate, then opened a practice of his own in a village west of Niagara Falls in Canada.

Whitman did not, however, give up his dream of becoming a minister. After less than two years in Canada, he returned to Rushville and began studying theology under Rev. Joseph Brackett, pastor of the Rushville Congregational Church. “I had not continued long when for want of active exercise I found my health become impaired by a pain in the left side which I attributed to an inflammation of the spleen,” he wrote. He “resorted to remidies [sic] with apparently full relief” and resumed his studies, but the pain persisted. Eventually, “I found I was not able to study & returned to the practice of my profession.”17 Whitman’s biographer, Clifford Drury, speculates that Whitman probably realized he was too old, at twenty-eight, to spend years studying for the ministry. He could go back to medical school for another four months, earn his MD degree, and make a reasonable living as a doctor.

Whitman reenrolled in the college at Fairfield in the fall of 1831. He completed another course of lectures; submitted a thesis on the topic of “caloric” (referring to the causes of heat in the body); and, on January 24, 1832, was awarded his degree. By the standards of his day, Whitman was a well-trained physician. Licensed in both New York state and in Canada, he had spent several years practicing medicine in frontier communities and was now fully credentialed. He established a practice in Wheeler, New York—a hamlet of about twenty-five families, forty miles south of Rushville. Initially, he lived in the home of an elder of the Wheeler Presbyterian Church. At some point Whitman bought a 150-acre farm, about midway between Wheeler and the nearby town of Prattsburg, and built a log cabin there.

As an itinerant country doctor, Whitman traveled widely around the region, on horseback, with his medical supplies in saddlebags. One of his staple “medications” was calomel, a compound of mercury and chlorine, which was widely used as a purgative in the nineteenth century. Medical theory of the era held that disease was often caused by an excess of blood or other bodily fluids. Whitman frequently bled his patients (as well as himself) and administered purgatives in an effort to restore balance to the body’s “humors.” Like other small-town doctors, he served as his own pharmacist. He bought drugs in crude form in bulk, pulverized them with a mortar, and produced his own pills. He owned a set of amputating knives and surgical saws. He also had a dental kit that included peg-type false teeth.

At thirty, Whitman was socially reserved, with what many thought a stern demeanor. His surviving letters, both personal and professional, reflect a man with a strong sense of purpose. He also could be thin-skinned, defensive, and, especially in his later years, self-aggrandizing. He wrote well but spelled badly. His social life revolved around the church. He was a trustee of the Wheeler Presbyterian Church, taught Sunday school, was active in the American Bible Society, and regularly attended sunrise prayer meetings with other young men. Rev. Joel Wakeman, a Presbyterian minister and friend of Whitman’s, remembered him as “a strong temperance man” who campaigned tirelessly against the use of alcohol.18 Whitman probably did not approve of his mother’s tavern business.

Not long after moving to Wheeler, Whitman began to consider the possibility of becoming a medical missionary. He was heavily influenced by Elisha Loomis, a native of Rushville who had served as a missionary in Hawaii for the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions. The first organized missionary society in the United States, founded in 1810 and based in Boston, the board sponsored Presbyterian and Congregational missions around the world. After Loomis returned to Rushville in 1832, he often spoke in area churches, proselytizing about mission life. He found a receptive listener in Marcus Whitman.

Whitman first applied for a position as a missionary with the American Board in the spring of 1834. The board asked whether he would accept an appointment to the Marquesas Islands in the South Pacific. He declined, saying he had “some fears of a hot climate.”19 After several exchanges of letters, the board rejected his application, partly because of concerns about Whitman’s health and partly because he was single (the board preferred to send only married men to its missions, hoping to shield them from temptations involving native women). He reapplied six months later, at the urging of Rev. Samuel Parker, a preacher from Ithaca, New York, who was on a one-man campaign to send missionaries to “save” Indians in the West.

Parker had been galvanized by the story of the four Indians who had shown up in Saint Louis in a supposed search for the “white man’s Book of Heaven.” He was fifty-five years old, with a sick wife, three children, and no wilderness experience. Nonetheless, he asked the American Board to send him to Oregon Country in the spring of 1834. The board, citing Parker’s age and family responsibilities, declined. Described by a colleague as someone who was “exceedingly set in his opinions” and “inclined to self-applause,” Parker tried to make it on his own.20 He got as far as Saint Louis but had to turn back.

The board was not eager to establish a mission in Oregon. For one thing, its financial resources for new enterprises were limited. It was already supporting eighty individual outposts in Africa, China, India, and elsewhere around the world. Board members seemed ready to cede Oregon to one of their evangelical rivals, the Methodist Mission Board, sponsored by the Missionary Society of the Methodist Episcopal Church. A party of Methodists led by Rev. Jason Lee was already on its way to Oregon, with an expedition organized by Nathaniel Wyeth, a Boston ice merchant who hoped to make a fortune in the fur trade. Lee and his associates would establish a mission in the Willamette Valley, near present-day Salem, in September 1834.

Meanwhile, Parker continued badgering the board until it finally agreed to sponsor an exploratory journey to Oregon, but only if he could recruit volunteers and raise most of the money himself. Parker was nearing the end of a mostly fruitless tour of churches in western New York in late November 1834 when he stopped in Wheeler. Whitman was among those who heard him speak. The two men later met privately. “I have had an interview with the Rev. Samuel Parker upon the subject of Missions and have determined to offer myself to the Am. Board to accompany him on his Mission beyond the Rocky Mountains,” Whitman wrote in a December 2, 1834, letter to the board. “My health is so much restored that I think it will offer no impediment,” he added.21

After leaving Wheeler, Parker traveled about forty-five miles west to Amity, a rustic village on the Genesee River. Speaking in a log building that served as both schoolhouse and church, he repeated his plea for missionaries to go to Oregon. His audience included Narcissa Prentiss, a twenty-six-year-old unmarried Sunday school teacher who had recently moved to Amity with her parents and siblings. She too volunteered. Parker thought it unlikely that the American Board would accept an application from a single woman. Nonetheless, he sent a query to David Greene, secretary of the board. “Are females wanted?” he asked. “A Miss Narcissa Prentiss of Amity is very anxious to go to the heathen. Her education is good—piety conspicuous,” Greene demurred, writing, “I don’t think we have missions among the Indians where unmarried females are valuable just now.”22

Narcissa Prentiss was a model of piety. She had her first conversion experience when she was eleven and another at sixteen. Her mother, a devout pillar of Presbyterianism, did not allow her to read novels or other “light and vain trash,” but Narcissa found stimulation and escape in romanticized biographies of such women as Harriet Newell, a missionary who went to India with her husband in 1812 and died an early, celebrated death.23 She avidly read letters from missionaries published in the monthly Missionary Herald. She began to think about becoming a missionary herself when she was still in her early teens. “I frequently desired to go to the heathen,” she wrote in a letter to the American Board, although initially “only half-heartedly.” Narcissa vividly remembered the date when she decided to “consecrate” herself “without reserve” to missionary work: “the first Monday of Jan. 1824,” after a revival.24 When Samuel Parker showed up in her local church a decade later, she was ready to answer the call.

Narcissa was born on March 14, 1808, in Prattsburg, the third of nine children (and the eldest daughter) of Stephen and Clarissa Prentiss. Her parents were among the town’s first settlers. Stephen had cleared land for a small farm there in 1805; he later took over the operation of a sawmill and gristmill. A carpenter, he used lumber from the sawmill to build houses for the community. Sometime before Narcissa’s birth, he built a modest frame house, a story and a half high, for his growing family. The house still stands, although in a different location, and is maintained as a historic site in Prattsburg (now spelled Prattsburgh).

Rev. Joel Wakeman, who knew both the Whitman and the Prentiss families, described Stephen Prentiss as tall, “a little inclined to corpulency,” and “remarkably reticent for a man of his intelligence and standing.” Stephen served one term as a county judge and thereafter claimed the title Judge Prentiss. His business activities included, for a while, a distillery, much to his wife’s disapproval. Clarissa was “fleshy and queenly in her deportment,” someone who “possessed great weight of Christian character.” Both were reserved and solemn in public. “It was a rare thing,” Wakeman wrote, for either to “indulge in laughter.”25

Clarissa took the lead in her family’s religious life. She became a charter member of the Prattsburg Presbyterian Church when it was built in 1807 and later helped organize the Female Home Missionary Society of Prattsburg. She enrolled all her children in the local Youth Missionary Society. Stephen helped build the church but did not join it until 1817. He left after just a few years, in a tussle that may have involved the issue of temperance, and did not return to the fold until 1831. He had given up his interests in the distillery by then, apparently fearing the effect of drinking on his sons.26

Prattsburg in the 1820s was a fairly isolated community, with a population of about fourteen hundred. Roads were primitive, manufactured goods hard to come by. Families had to be self-sufficient. Narcissa learned how to weave and spin, sew, cook over an open fire, and make soap and candles. She was comparatively well-educated for a woman of her generation. She was a member of the first class of women to be enrolled in the Franklin Academy, a church-affiliated secondary school in Prattsburg. She completed one twenty-one-week term in April 1828, when she was twenty, and returned for a second term two years later. Among her fellow students at that time was an aspiring missionary named Henry Harmon Spalding.

Narcissa’s surviving letters and journal show that she was a graceful, accomplished writer. In different circumstances and in a different era, she might have found success in the literary world. But her options were limited. She briefly taught kindergarten in two nearby schools, but by 1832 she was living at home and helping her mother with household chores. She spent most of her twenties “waiting the leadings of Providence concerning me,” as she put it.27 The average American woman in the 1830s was married by twenty-one; Narcissa was approaching spinsterhood as she waited for directions from Providence.

Narcissa’s friends and acquaintances described her as a woman of medium height, about five feet five and, like her mother, somewhat “fleshy.” She had fair skin, gray-blue eyes, and thick, tawny hair, which she parted in the middle and wore in a tight bun at the back of her neck. Her eyes often troubled her; she needed glasses for reading and sewing. She had erect posture and usually dressed severely, in plain, high-necked, long-sleeved, full-skirted dresses. She was widely admired for the quality of her singing voice—a clear, strong soprano, which she used to good effect in church services. “She was not a beauty,” wrote Rev. Wakeman, “and yet when engaged in singing or conversation there was something in her appearance very attractive.”28

As the eldest daughter in a large family, Narcissa had many household responsibilities and few idle hours. Her social life, like Marcus’s, revolved around the church. She taught Sunday school. She hosted women’s prayer meetings in her home. She continued to dream of becoming a missionary in an exotic place. Still, she could do little to shape her own future beyond hope for a marriage proposal from a man who shared her values. As she discovered, single women did not receive appointments from the American Board. If Narcissa were to “go to the heathen,” she would have to do so as the wife of a missionary.

In mid-January 1835, Marcus Whitman learned that the board had appointed him as an “assistant missionary” to accompany Parker on a scouting expedition to the West in the spring. He made arrangements to sell his farm and close his medical practice. He then briefly visited Parker, who had returned to his home in Ithaca; Parker told him about the would-be female missionary in Amity and suggested he call on her. Whitman had already indicated that he was willing to “take a wife, if the service of the board would admit.”29 When he found out that Narcissa was willing to go to Oregon, he may have seen it as a sign that Providence intended them to go together as husband and wife.

Marcus Whitman and Narcissa Prentiss were born within twenty-five miles of each other and had spent most of their lives in the same general area of New York. Marcus had once attended a prayer meeting in the Prentiss home, but Narcissa was living and teaching kindergarten in a nearby community at the time.30 They apparently did not meet each other until February 21, 1835, when Marcus arrived in Amity. They spent only a few hours together, spread out over the next two days, but by the time he left, they were engaged. The two would not see each other again for nearly a year.

In Saint Louis, Whitman and Parker met with officials of the American Fur Company and received grudging permission to travel with the company’s caravan to the Rocky Mountain rendezvous, an annual gathering of trappers, traders, and Indians. The two men hoped to find Indian guides there who could help them explore the region and locate potential mission sites. From Saint Louis they took a steamboat to Liberty, Missouri, about four hundred miles upriver, where the caravan was being assembled. Writing to Narcissa on April 30, 1835, shortly before the caravan left Liberty, Whitman said he thought the trip across the Great Plains and over the Rockies would be easier than he and Parker had expected. “Many obstacles to our journey as conceived by us do not exist,” he wrote. “We are assured of abundant protection until we shall have passed the mountains, and beyond the mountains we are told we shall not have much to fear from the Indians.”31

The caravan that year included about sixty rough-edged, hard-drinking, unchurched fur traders, hunters, and voyageurs, hauling tons of supplies to exchange for pelts at the rendezvous. The missionaries disapproved of their intemperate habits, and the men, in turn, resented the presence of the missionaries. “Very evident tokens gave us to understand that our company was not agreeable, such as the throwing of rotten eggs at me,” Whitman wrote to Greene, the board’s secretary, with what might have been a touch of dry humor.32 Parker was even more disliked. A Hudson’s Bay Company trader memorably described him as “a missionary from the United States of the presbiterian [sic] persuasion who sends us all to Hell—honest man—with as little ceremony as I would (at this moment for I am very hungry) drive a rump steak into my bread basket.”33

Whitman gained a measure of respect after an outbreak of cholera forced the caravan to halt for about three weeks near present-day Council Bluffs, Iowa. More than a dozen men, including the caravan’s commander, were sickened, and three eventually died.34 Whitman had had no direct experience treating the disease—a severe infection of the intestines, spread by contaminated food or water—but he knew enough to associate it with lack of cleanliness. He recommended that the men be moved from a camp in a low-lying area bordering the Missouri River to “a clean and healthy situation” on higher ground. In a letter to Narcissa, he attributed the outbreak to the traders’ consumption of alcohol and dirty water. “It is not strange that they should have the cholera,” he wrote, “because of their intemperance, their sunken and filthy situation.”35

The caravan reached the rendezvous site, on the Green River in western Wyoming, on August 12, 1835, several weeks later than expected, due in part to the cholera outbreak. Thousands of Indians and several hundred trappers were waiting, impatiently. It would have been an impressive sight: Indians, trappers, and too many horses to count, in a shifting mosaic of color and motion, spread out over a long, broad meadow. If Whitman was awed, he didn’t confide it in his travel diary. “Arrived at rendezvous on Green river,” he reported, laconically. “Most of the traders and trappers of the mountains are here, and about two thousand Shoshoni or Snake Indians, and forty lodges of Flathead & Napiersas [Nez Perce], and a few Utaws [Utes].”36

News that a doctor had arrived spread quickly. The next day, Whitman removed a three-inch iron arrowhead from the back of Jim Bridger, one of the most celebrated “mountain men” of the frontier era. The operation—performed without anesthesia—was not an easy one for either patient or physician. The arrowhead had been lodged in Bridger’s body for three years, a reminder of a skirmish with Blackfeet Indians. It had hooked into a bone and “a cartilaginous substance” had grown around it. Its removal impressed the trappers and Indians who gathered around to watch. Whitman also dug an arrowhead from the shoulder of one of the caravan’s hunters. After that, Parker wrote, “calls for medical and surgical aid were almost incessant.”37 Both Jim Bridger and another mountain man, Joe Meek, would later send their young, mixed-race daughters to school at the Whitman Mission.

Neither Whitman nor Parker had direct, firsthand knowledge about the Indians that they hoped to evangelize. Their primary source of information turned out to be Sir William Drummond Stewart, a Scottish nobleman who had been adventuring in the American West for three years. Stewart had worked, traveled, and formed friendships with a number of luminaries in the fur trade, including Bridger and Meek. He had attended two previous rendezvous and had a trader’s understanding of the social geography of the region. Stewart told the missionaries that the Flathead and Nez Perce were “very friendly to the whites and not addicted to steal,” that they lived in “fertile vallies [sic] capable of good cultivation,” and that any missionaries who settled among them “would be free from hostile attacks from other tribes.”38

Apparently on Stewart’s advice, Whitman and Parker met with a group of Nez Perce and Flathead headmen on August 16. Through an interpreter—a trapper named Charles Compo, a French Canadian married to a Nez Perce woman—they received the impression that the Indians were eager to have missionaries come and live on their lands. The headmen “expressed great pleasure in seeing us and strong desires to be taught,” Whitman wrote in his travel diary, later sent to the American Board.39 He and Parker decided to split up. Whitman would return east with the fur company and arrange to bring a party of missionaries to Oregon the next year; Parker would continue traveling west, scouting locations.

Parker, escorted by Compo, Compo’s wife, and a group of Nez Perces, left a few days later. Whitman stayed on for another week. During that time he met a Nez Perce boy named Tackitonitis (also written “Tack-i-too-tis”) who spoke a little English. Whitman wanted to take him east so he could learn more English and serve as an interpreter for the missionaries. After some discussion, the boy’s father agreed. Whitman immediately began trying to acculturate the youth, renaming him “Richard.” A few days later, another Nez Perce father asked whether his son, Ais, could go too. Whitman agreed; he called this boy John.

Whitman and the two young Nez Perces left the rendezvous with the caravan on August 27, 1835. About four and a half months later they arrived in Amity, where Whitman learned that the Prentiss family had moved six miles north to the small village of Angelica. He and the boys reached Angelica around December 10. After a brief visit with Narcissa, Whitman sent the boys to one of Parker’s relatives in Ithaca and hurried sixty miles north to his mother’s home in Rushville. He spent the rest of the winter there, working on arrangements for what was now officially the American Board’s Oregon Mission.

Whitman’s most pressing concern was to find at least one other couple who could go to Oregon. Board secretary David Greene provided him with a few names, including Rev. and Mrs. Oliver S. Powell of Amity, friends of Narcissa. They were ruled out because Mrs. Powell had recently given birth. Another missionary couple who had expressed an interest decided instead to go to Astoria, on the Northwest coast. In a letter dated December 30, 1835, Greene offered Whitman some advice about the qualifications of suitable companions but didn’t give him any more names. Whitman would have to do his own recruiting.

It turned out that few prospective missionaries were willing to accept an assignment in Oregon. Exotic locations overseas—in Africa, China, India, the “Sandwich Islands” (Hawaii), and elsewhere—had more appeal. Most assignments were in densely populated areas, offering more evangelical bang for the buck, as it were: potential converts could number in the thousands instead of the hundreds. The fact that Whitman wanted to take women on an overland trip across the Rockies proved another barrier to his recruitment efforts. Greene, for one, wasn’t sure it was a good idea. “Have you carefully ascertained & weighed the difficulties in the way of conducting females to those remote & desolate regions and comfortably sustaining families there?” he asked.40

In a two-thousand-word appendix to his travel journal, mailed to the board from Rushville on December 17, Whitman expressed confidence that a wagon could be taken over the mountains, that women could ride in it whenever they wanted, that the missionaries could take cows and cattle with them on the journey so they could have milk and meat when they reached their destination, and that they could quickly become self-sufficient with a little bit of help from the Hudson’s Bay Company. It would not be the last time that Whitman demonstrated unfounded optimism in his approach to the Oregon Mission.

Whitman had promised to bring the Nez Perce boys back to their families by summer, which meant he would need to be on his way to the Missouri frontier by mid-February 1836. With just a few weeks left to find at least one other married couple to go with him and Narcissa to Oregon, he turned to Henry Spalding, who had just been appointed as a missionary to the Osage Indians in what is now eastern Kansas. Of all the missionaries who went to Oregon under the auspices of the American Board, Spalding had the roughest start in life. He was born to an unmarried mother in a log cabin near Wheeler on November 26, 1803. His father never acknowledged him. His mother gave him up when he was little more than a year old, binding him over to foster parents. When he was seventeen, his foster father became enraged over something, whipped him, and threw him out of the house. Years later, Spalding bitterly recalled trudging down the road to a neighbor’s house, “sad, destitute, 17, crying, a cast off bastard wishing myself dead.”41

A schoolmaster named Ezra Rice took him in. Spalding stayed with him for four years, working for his room and board and attending the “common school” where Rice taught. Spalding’s education was limited; at twenty-one he read with difficulty and had only a rudimentary command of grammar and arithmetic. He was also tenacious, hardworking, and determined to make a better life for himself. In the fall of 1825 he enrolled in the Franklin Academy, a newly established college preparatory school in Prattsburg. He was older than most of his classmates, socially inept, almost cripplingly shy, terrified of public speaking, and undoubtedly poorly dressed. Pressed for money, he dropped out after just one twenty-one-week term. He worked as a farm laborer, picked up occasional stints as a primary school teacher, saved money, and eventually returned to the academy. With help from a tuition waiver and a small scholarship from the American Education Society, he was able to complete a full two years at Franklin, graduating in 1831.

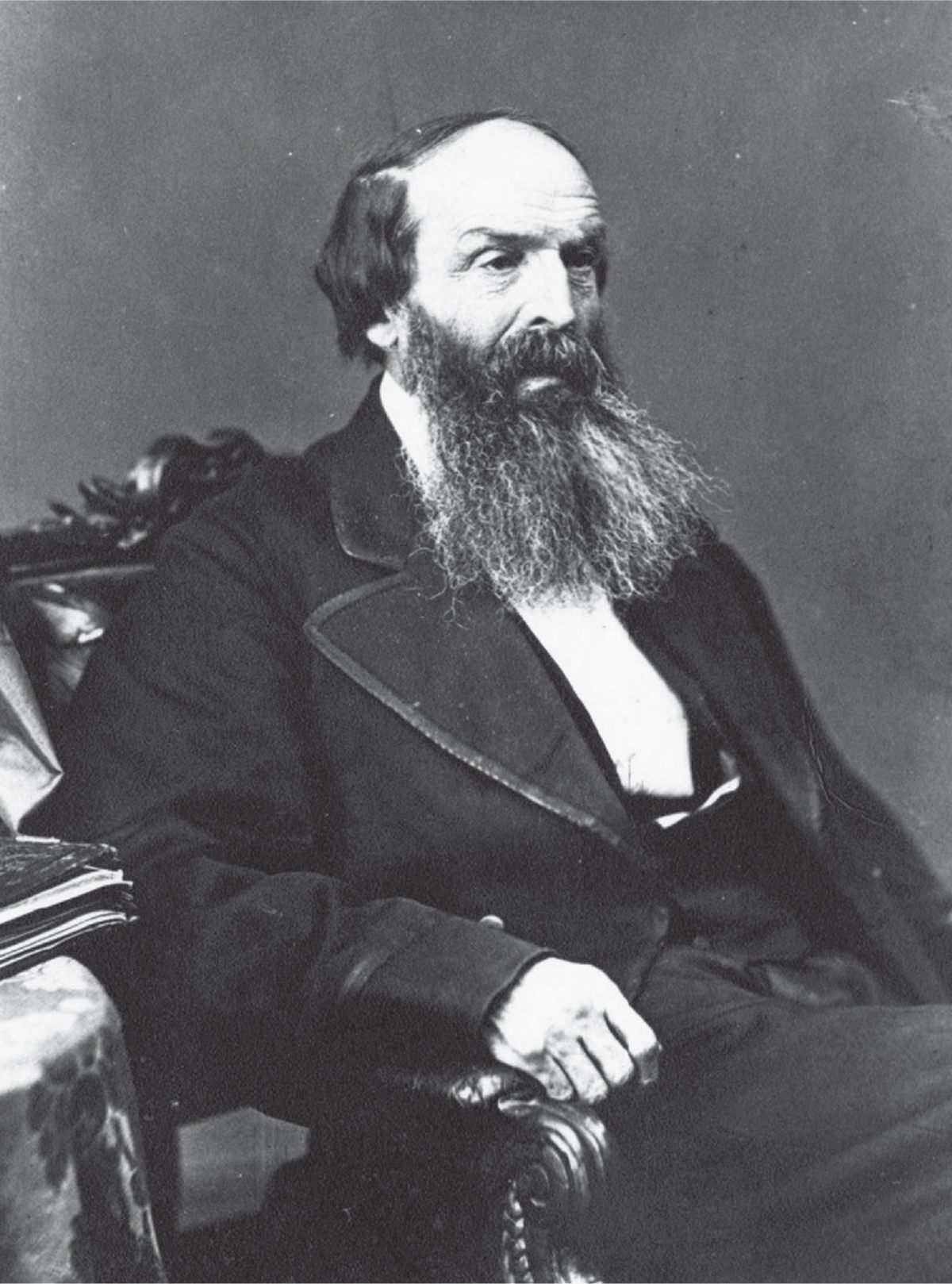

Missionary Henry Harmon Spalding, photographed in New York in 1871 by famed Civil War photographer Mathew Brady. After the deaths of the Whitmans in 1847, Spalding became a tireless champion of the idea that Marcus Whitman had “saved” Oregon. Presbyterian Historical Society, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Spalding had his first spiritual awakening during a revival at the Prattsburg Presbyterian Church in 1825. He had a second three years later, when he read a religious tract titled “The Conversion of the World or the Claims of Six Hundred Millions, and the Ability and Duty of the Churches Respecting Them.” The message, in eighty-five hundred words, was that Christians had an obligation to see that the gospel was preached to the entire world, in preparation for Armageddon (“end times”), the Second Coming of Christ, and the creation of a world without sin or disease for the righteous. Spalding read and reread the tract and vowed to become a missionary. Neither he nor his fellow missionaries were aware that Indian prophets on the Columbia Plateau had similar views about a time when “the world will fall to pieces,” after which a powerful nonmortal being would appear and show the way to a restored and better world.

In 1830, when Spalding was beginning his final year at the Franklin Academy, he asked an acquaintance if she knew of any pious young women who might be interested in missionary work. She put him in touch with Eliza Hart, the daughter of a prosperous farmer in Holland Patent, about 140 miles east of Prattsburg. Eliza, four years younger than Spalding, had all the advantages he lacked: a stable home, loving parents, brothers (three), sisters (two), and a wide circle of friends. What they had in common was a deep religiosity. Eliza had been “born again” at age eighteen. She was a member of the Presbyterian Church in Holland Patent, “of a serious turn of mind,” known for pressing religious tracts on her associates.42 She was attending a seminary for young women around the time that she began writing to Spalding. They corresponded for a full year before they met in person, when Spalding called on Eliza at her parents’ home, in October 1831, shortly after he graduated from the academy.

Spalding was a sharp-featured man, muscular from the farm-work he did to earn money during the summers, with deep-set eyes, thick brows, a high forehead, and a hairline that was in full retreat by the time he was thirty. Photos taken in later life show him with a full, bushy beard, streaked with gray, and a scowl that would do justice to an Old Testament prophet. A word often used to describe Henry Spalding was “severe.” He had a reputation for being rigid, abrasive, quick to take offense, and slow to let go of a grudge. Eliza was a gentler soul, intelligent but self-effacing. Whatever she thought of his personality, she agreed to continue writing to him.

Like Whitman, Spalding wanted to enter the ministry. His degree from the Franklin Academy allowed him to enroll as a junior in Western Reserve College, a small, Presbyterian-affiliated school in Hudson, Ohio. All but one of the six faculty members were clergymen. Most were fervent abolitionists. Spalding disapproved of their activism. In a letter to Eliza’s father, he complained that the “raging” about abolition “has about ruined this college.”43 But he appreciated the school’s mix of vocational and classical instruction. All students were required to work at least two hours a day in the college shops. He learned how to make barrels, build furniture, and run a printing press—practical skills that would serve him well in Oregon.

Spalding visited Eliza again in Holland Patent at the end of his first year at Western Reserve. He apparently proposed; she accepted and returned with him to Ohio. There is little record of this interlude in their lives. Eliza may have attended a school for young women. She told her family that Spalding was tutoring her in algebra and astronomy. He graduated in August 1833 with a thesis titled “Claims of the Heathen on the American Churches” and began making plans to attend Lane Theological Seminary, near Cincinnati.44 He was giving some thought to becoming a missionary in China. Meanwhile, Spalding wrote to Eliza’s father, formally asking permission to marry her. He made his case in very dry terms. “My anticipations in relation to Sister Eliza have been more than realized,” he wrote, adding that marriage “will not at all retard our studies.” Eliza was somewhat more effusive. “I trust, dear parents, that you will not hesitate to grant the request Mr. Spalding has now made,” she wrote in a note at the bottom of Spalding’s letter. “I have found in him a kind and affectionate friend, one in whose society I should consider it a high privilege to spend the days of my earthly pilgrimage.”45 They were married on October 13, 1833, in Hudson. Spalding refused to spend the $40 it would have cost them to travel to her parents’ home for the wedding.

They rented a house near the seminary and took in boarders to make ends meet. Eliza served them “good, plain fare”—no tea, coffee, or sweets, which were considered “stimulants” and thus threats to temperance. The school, headed by Rev. Lyman Beecher (father of Uncle Tom’s Cabin author Harriet Beecher Stowe), permitted women to attend classes. Eliza studied Greek and Hebrew, among other subjects. She also attended Beecher’s weekly lectures on theology. She probably had the broadest education of all the women in the Oregon Mission and would prove to be the most adept linguist.

Spalding completed his studies, was ordained, and applied to the American Board for an appointment as a missionary in August 1835. He submitted two letters of recommendation. One, signed by two of his former pastors, said he had “a strong and vigorous constitution,” had been “inured to hardship from infancy,” and was “a person of undoubted piety.” The other, from Artemas Bullard, head of the Foreign Mission Society of the Presbyterian Church, was something less than a full-throated endorsement. Bullard described Spalding as “not remarkable for judgment & commonsense…too much inclined to denounce or censure those who are not as zealous & ardent as himself…a little too much inclined to be jealous.” He went on to say that he thought Spalding might mellow over time. As for Eliza, Bullard wrote: “His wife is very highly respected & loved by a large circle of friends…. She is one of the best women for a missionaries [sic] wife with whom I am acquainted.”46

The American Board’s requirements for missionaries were minimal. Applicants needed only to be pious, married, and in reasonably good health. There was no expectation that candidates demonstrate cultural sensitivity, adaptability, humility, or language skills. Spalding met the standards. He was assigned to a station among the Osage Indians, who had been forced to leave their homelands in the Mississippi River Valley and move west of the Missouri. Eliza’s father was not happy about the news but gave them a horse and a light wagon as a going-away gift.47 They were in Prattsburg in October 1835, preparing to leave for the Osage station, when Eliza gave birth to a stillborn daughter. She was still recovering two months later when Marcus Whitman asked them to change their plans and go to Oregon instead.

Many years after the deaths of all the principals, a story emerged that Henry Spalding had once been in love with Narcissa Prentiss, had proposed to her, and had been spurned. It was hinted at in a 1911 history of Oregon; elaborated on in Waiilatpu: Its Rise and Fall, a work of historical fiction published in 1915; and widely accepted as fact by the 1950s, as in this passage from a book published by the University of Nebraska Press in 1956 and reissued in 1979: “An illegitimate child, obsessed with shame and a feverish desire to right himself by righting the world, Spalding some years before had proposed to Narcissa and had been rejected. Later the tall, dour youth had married Eliza Hart, as dark and scrawny as Narcissa was golden and buxom.”48

It is true that Narcissa and Henry knew each other. They had been members of the same church in Prattsburg. Narcissa had attended one twenty-one week term at the Franklin Academy when Spalding was finishing his education there. But the evidence of a thwarted romance is ambiguous at best. Clifford M. Drury, dean of the historians of the missionary era, flatly dismissed the idea in his biography of Spalding, published in 1936, but found it credible when he published a biography of Whitman, one year later. Drury said he changed his mind largely on the basis of “new evidence”—a letter written by Harriet Prentiss Jackson, Narcissa’s youngest sister, to Eva Emery Dye, a writer of historical fiction. According to Drury, the letter included the following claim about Spalding: “He was a student when a young man in Franklin Academy, Prattsburg the place of our nativity, and he wished to make Narcissa his wife, and her refusal of him caused the wicked feeling he cherished toward them [Marcus and Narcissa] both.”49 The letter was reportedly written in 1893, more than sixty years after the purported proposal, by a sister who would have been too young to know much about events at the time. It’s not clear whether Drury ever actually saw such a letter or simply heard something about it secondhand. In any case, no such document is on file today in the archives of the Oregon Historical Society, where Drury said it was located.50

Drury also reinterpreted a remark that Spalding made when he first heard that Narcissa was engaged to Marcus Whitman and planning to become a missionary in Oregon. By his own account, Spalding told friends at the time that he would not go on any mission with Narcissa because he questioned her judgment. Drury decided the remark meant that Spalding was still jealous and bitter because she had refused his proposal. But it could have meant simply that he thought Narcissa was not suited for life as a missionary—and indeed, it would turn out that she was not.

The Spaldings were making final arrangements before leaving for their assignment with the Osages when they received a letter from Whitman, begging them to go to Oregon instead. Whitman did not hide his desperation. The American Board would not send a mission to Oregon unless at least one member of the party was an ordained minister. Further, it was imperative that the party leave within a few weeks in order to connect with the fur company’s caravan in Saint Louis. The caravan would not adjust its schedule to accommodate any missionaries, and the missionaries would not be able to make the journey without the guidance and protection of the caravan. Spalding continued to plan for his original post but notified the board that he would join the Whitman party if necessary. “If the Board and Dr. Whitman wish me to go to the Rocky Mountains with him, I am ready,” he wrote to Greene on December 28, 1835. “Act your pleasure.”51

Greene expressed some reservations about Spalding’s suitability for a mission in Oregon. “I have some doubt whether his temperament well fits him for intercourse with the traders and travellers in that region,” he wrote to Whitman. However, “as to laboriousness, self-denial, energy and perseverance, I presume that few men are better qualified than he.”52 By the time Whitman received that letter, in mid-February 1836, the Spaldings had already left Prattsburg for what they still assumed would be a mission in Kansas. Whitman raced after them and begged them to change their plans. Henry left the decision to Eliza. She decided that “duty seemed to require” a new “place of destination.”53 The Spaldings agreed to wait for the Whitmans in Cincinnati and travel together across the continent. Marcus then returned to Angelica to marry Narcissa.

The wedding took place on the evening of February 18, 1836, in the Angelica Presbyterian Church. She was almost twenty-eight; he was thirty-three. Narcissa wore a dress of black bombazine (a fabric made of tightly woven silk and wool), which she took with her to Oregon. Tackitonitis, the Nez Perce youth that Whitman had renamed “Richard,” was among the wedding guests. The couple had been engaged for a year but had spent only a few hours in each other’s company. They had agreed to marry “somewhat abruptly,” Narcissa reportedly told an acquaintance later, “and must do our courtship now we are married.”54

The ceremony ended with a hymn titled “Yes, My Native Land! I Love Thee!” As the song built, through stanzas that included the refrain “Can I leave thee, can I leave thee / Far in heathen lands to dwell?,” the congregation was overcome with emotion. In the morning the couple would set off for a distant land that was not yet part of the United States. No white woman had yet crossed the continent. It seemed unlikely that either Marcus or Narcissa would ever return to their “native land” again. One by one, according to a story that was told later, the voices faltered, until only Narcissa could be heard, in a clear soprano, singing the last verse: “Let me hasten, let me hasten / Far in heathen lands to dwell.”55

The next day, the Whitmans left on the first leg of their long journey to Oregon.