CHAPTER 1

Just a Little Storm

Hurricane Katrina began on August 19 as a tropical disturbance. That means it was just a little storm with winds blowing in every direction.

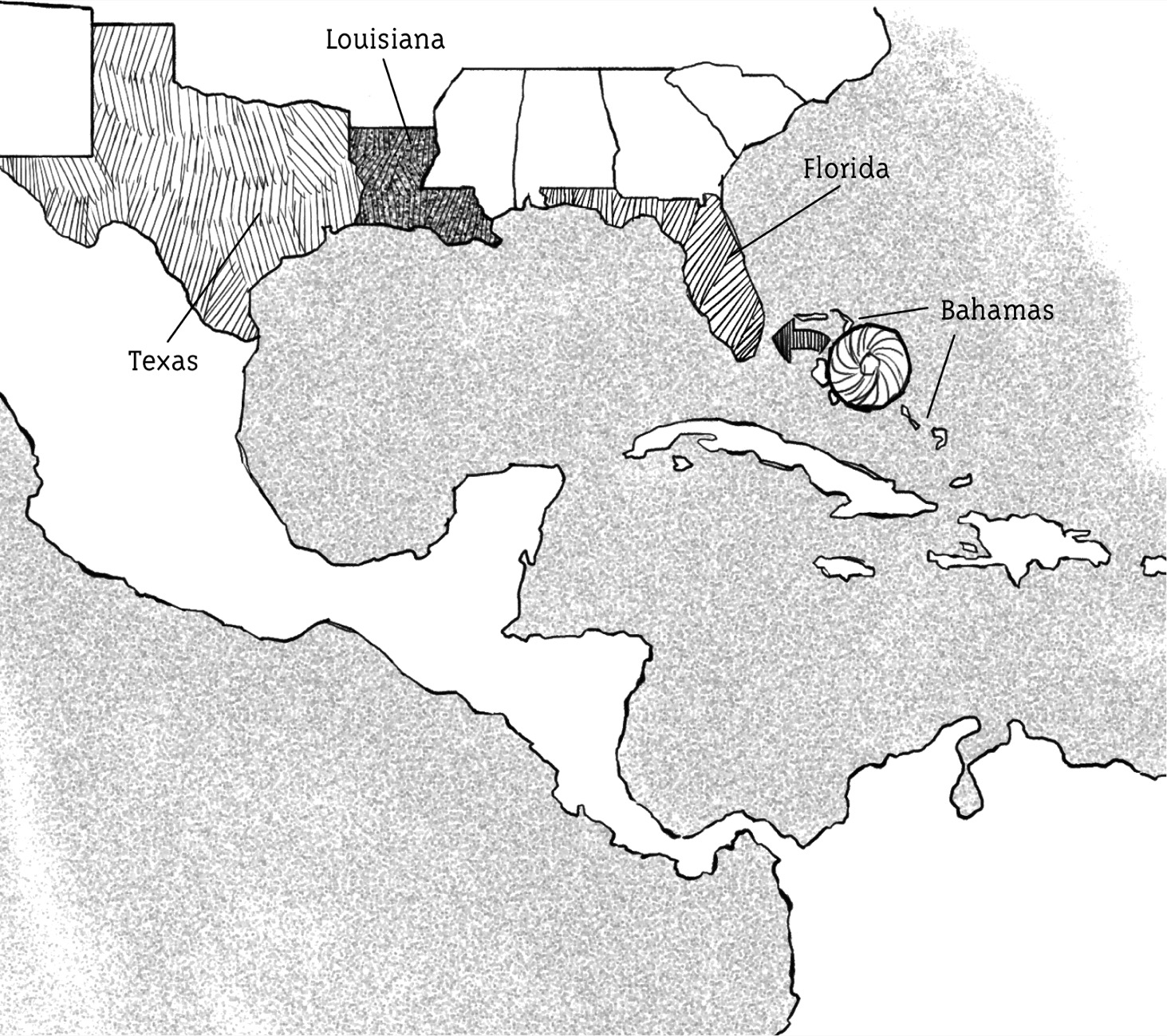

Meteorologists watched the little storm move across the Atlantic Ocean from the west coast of Africa, north of the equator. They knew that hurricanes form in warm, moist air. Ocean water north of the equator during late summer is perfect for hurricanes.

By the time the little storm got close to the Bahamas late on August 22, 2005, it was stronger. Winds whipped at about twenty-five miles per hour, making small trees sway.

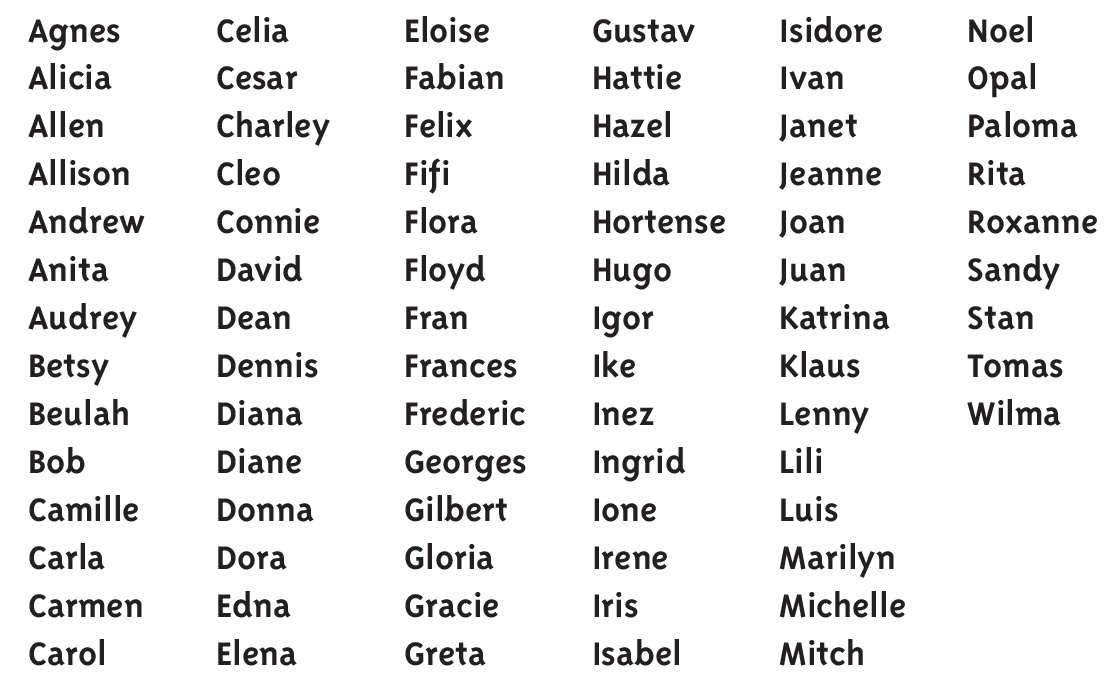

About two days later, the storm moved northwest through the Bahamas with winds of about forty miles per hour. A wind that strong is hard to walk in. Trees can lose small branches. The storm also rotated in a circle. It was at this point that the tropical storm was named Katrina. And it was heading toward South Florida.

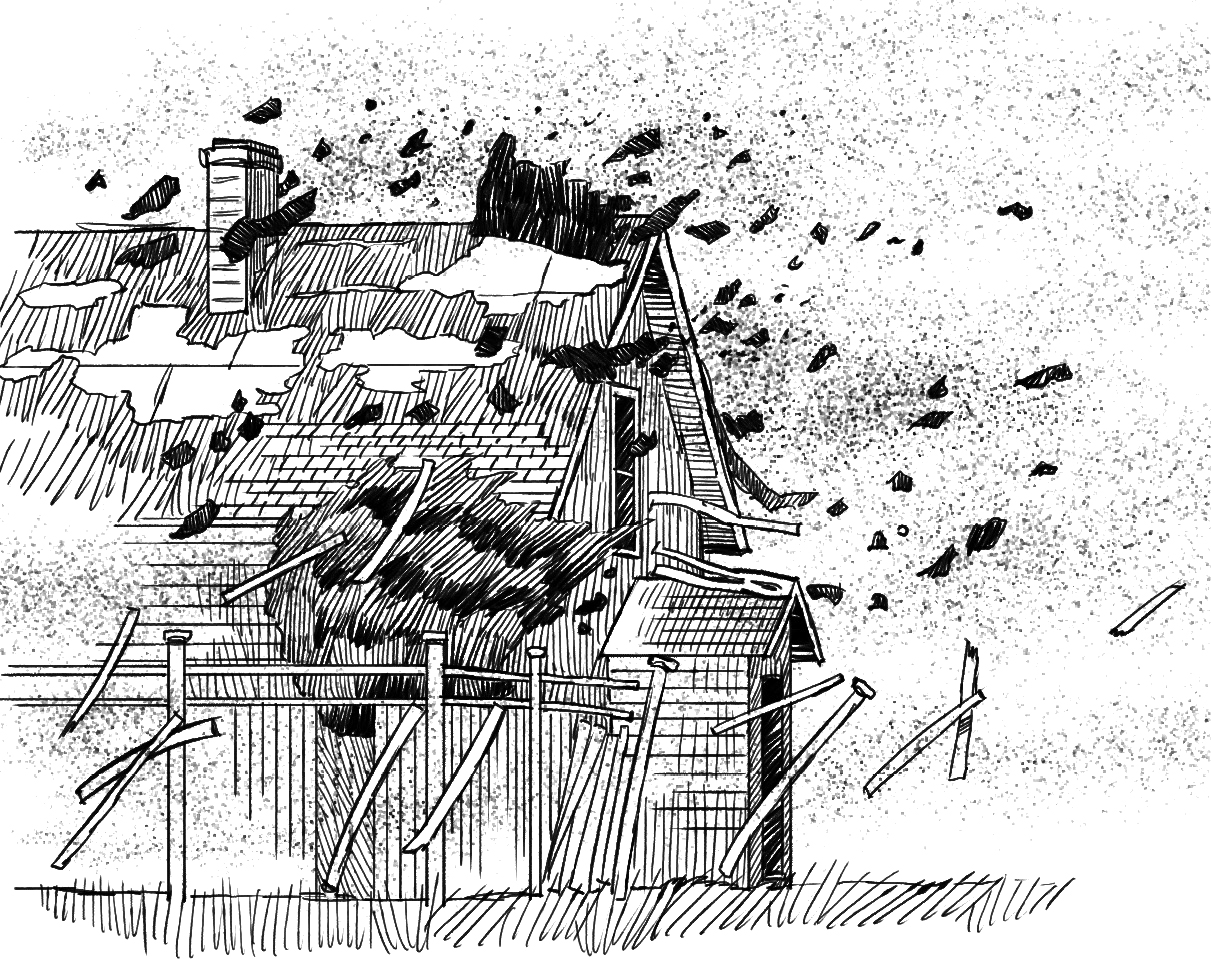

By August 25, Katrina was close to becoming a hurricane. Hurricanes have powerful winds of at least seventy-four miles per hour. (They are called cyclones in some areas of the world and typhoons in others.) Their fierce winds rotate around a center core called the eye. Winds that strong can uproot trees, toss cars around, and blow the roofs off houses!

Hurricanes form in the North Atlantic Ocean in late spring, summer, and early fall. They occur most often between mid-August and October. These unwelcome visitors can blow into land areas in the Caribbean Sea, the Gulf of Mexico, and the North Atlantic.

Most storms weaken when they reach land. That’s because they no longer are getting power from warm ocean air. Katrina, however, got stronger as it blew its way to southern Florida on August 25. The powerful storm turned into a hurricane about two hours before it landed, causing flooding and several deaths. Even so, at that point, Katrina was still not considered an unusual storm.

Unfortunately, Katrina was just getting started. As the storm traveled farther west over the Gulf of Mexico, it wound through an area called the Loop Current, gaining more strength from deep warm water. It grew wider, covering a larger and larger area. And the winds rotated faster and faster.

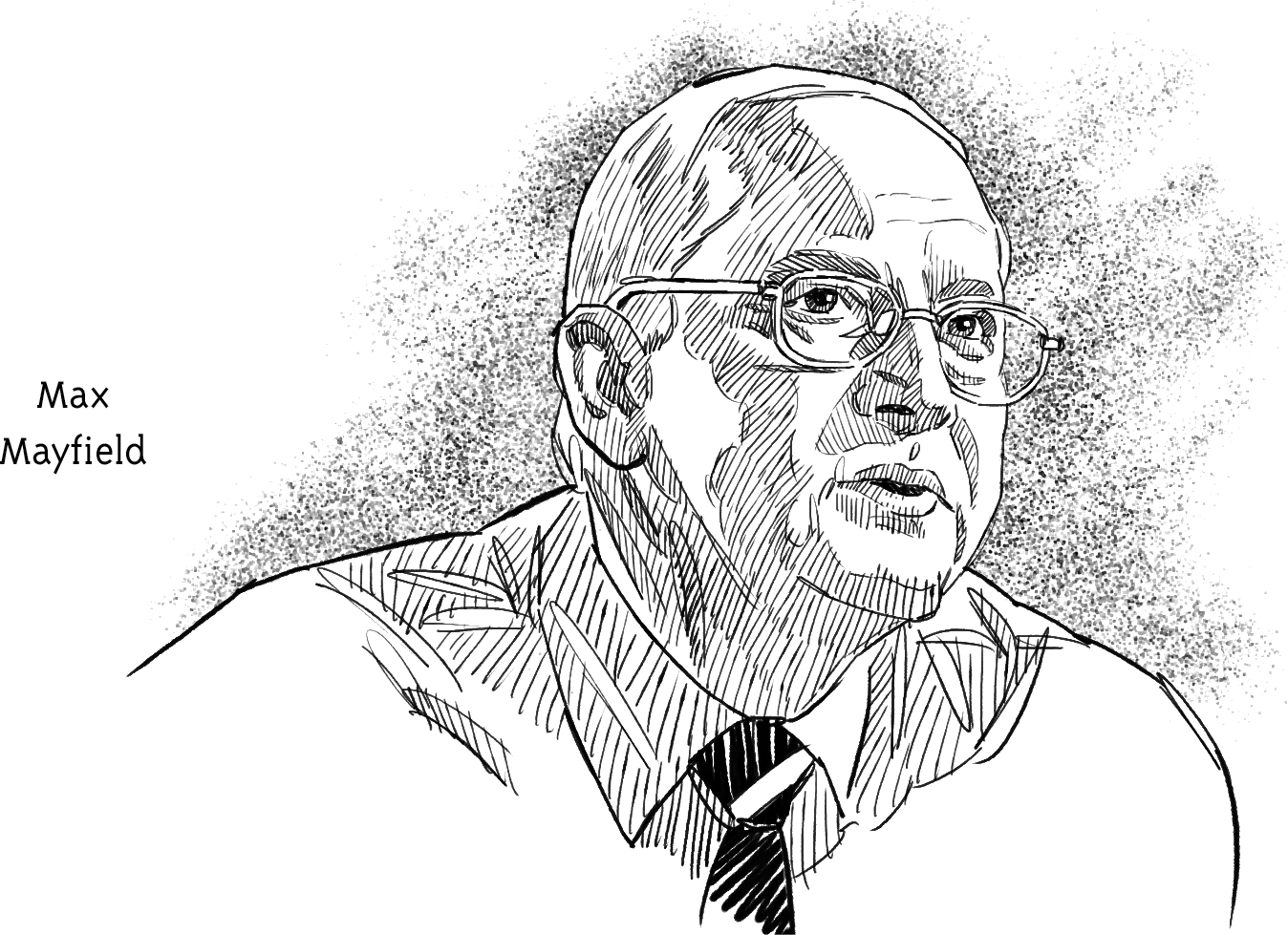

Max Mayfield was the National Hurricane Center director. He was very worried. It wasn’t just the damage from high winds and rain that concerned him. When a hurricane reaches land, it will push a wall of ocean water along with it. This wall of water is called a storm surge.

Mayfield saw that Katrina was moving straight toward New Orleans, the largest city in Louisiana.

A huge storm surge there would spell disaster.

Why?

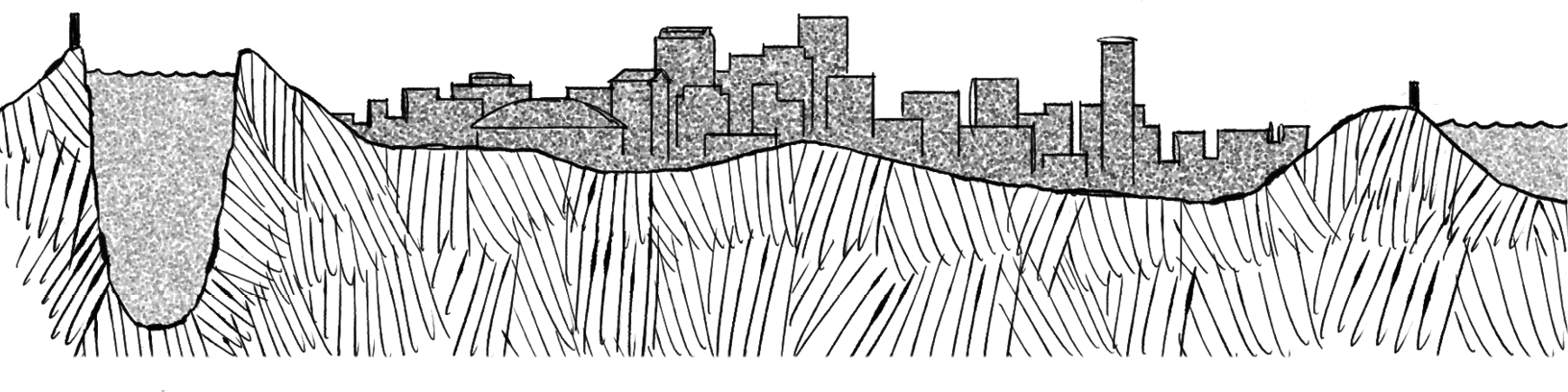

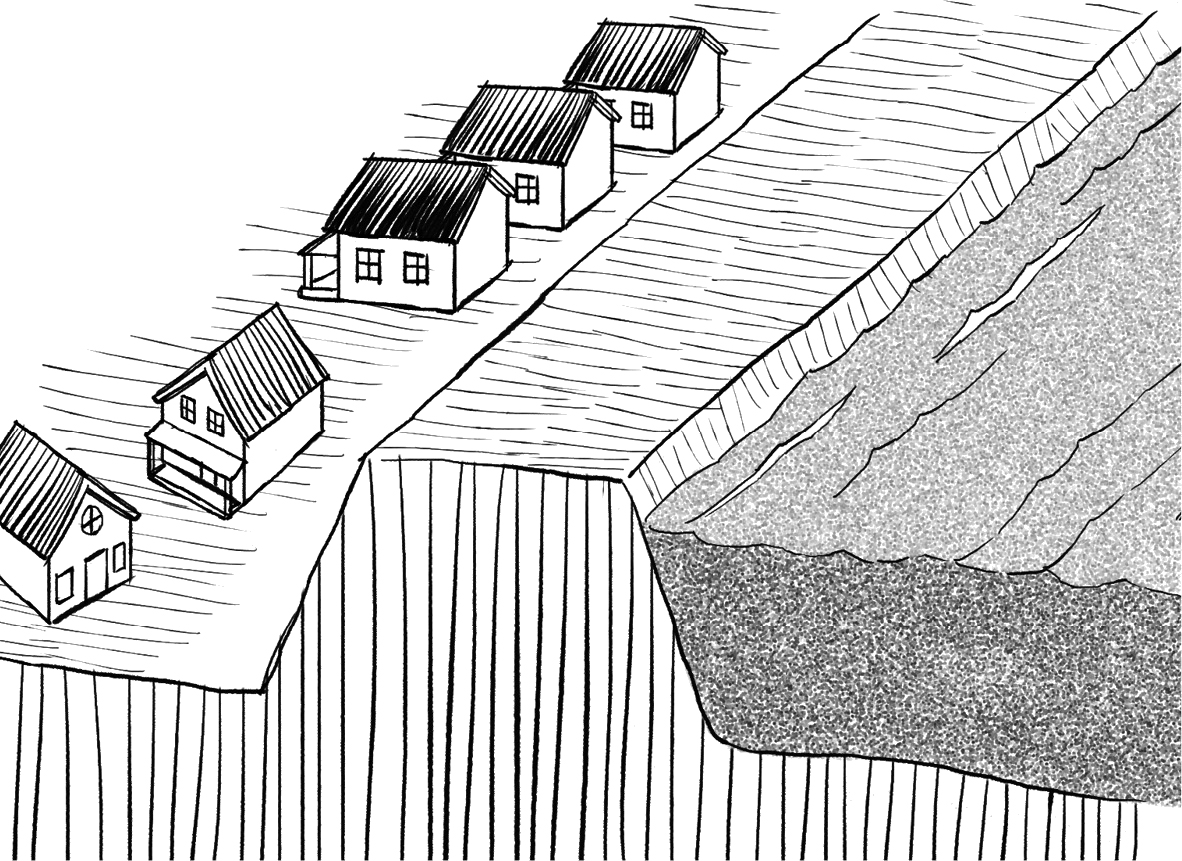

New Orleans is shaped like a huge soup bowl and is nearly surrounded by water. Much of the city lies at or below sea level. If water gets in, terrible flooding can occur.

To keep water out, the city was protected by barriers called levees. But even before Hurricane Katrina hit, there was doubt about whether the levees would stand up to a superstorm. Parts of the levee system had been recently rebuilt. The new structures had not yet been tested by a hurricane as powerful as Katrina. Water could be pumped out if the storm surge went over the levees. But what if the levees broke or collapsed? That would mean terrible trouble.

On Saturday evening, August 27, Max Mayfield called Ray Nagin, the mayor of New Orleans, Kathleen Blanco, the governor of Louisiana, and the governor of Mississippi, Haley Barbour. He urged them to tell people to get out of the area: A monster storm was coming! But Mayor Nagin did not want to order people to leave. He worried about what would happen if hotels and businesses were left empty. He worried about crime. So instead, he urged people to leave, but did not order them to do so. The choice was up to them.

At 10:11 a.m. on Sunday, August 28, the National Weather Service issued the most serious warning yet to people who were in Southeastern Louisiana and the Mississippi Gulf Coast: “URGENT WEATHER MESSAGE

. . . HURRICANE KATRINA . . .

A MOST POWERFUL HURRICANE WITH UNPRECEDENTED STRENGTH . . .” (Unprecedented means “never before seen.”)

The message warned what would happen. Wood-frame buildings would be completely destroyed, and concrete structures would be severely damaged. Windows would blow out, and houses could explode. The air would be filled with flying debris, including trees, refrigerators, and even cars! Anyone outside faced almost certain death.

Katrina had become a Category 5 hurricane. Now the hurricane had winds of 175 miles per hour! That’s as fast as a high-speed train. At this point, Mayor Nagin ordered the first mandatory evacuation in New Orleans’s history. Mandatory means that leaving the city was no longer a choice. Evacuation means getting out. The mayor told the city residents, “We’re facing the storm most of us have feared.”