Intelligent transport systems (ITS) is an information and communication technology that provides solutions mainly on reducing traffic accidents and congestion. It has been under continuous development since the early 1980s.

Despite there being some early ITS solutions that only adopt autonomous on-board equipment (e.g. ranging sensor and machine vision) to gather information from the surrounding environment, most of the ITS solutions use cooperative approaches, where the traffic-related information is communicated between vehicles and/or roadside infrastructure [PIO 08]. Although an autonomous approach has an advantage in that it does not rely on other participants, it has the obvious limitations in terms of vision and detection ranges as shown in Figure 2.1. A cooperative approach based on single or multiple hops, intervehicle communication (IVC), can better overcome the range limitations and provide a more flexible ITS solution.

Figure 2.1. Autonomous approach versus cooperative approaches

However, the development of an IVC technique is not like developing other civil wireless communication techniques. The IVC has different features as follows:

To develop a real-world IVC technique, these features have to be fully considered. Fortunately, compared with other civil wireless communication techniques, an IVC technique can utilize two extra network supports as follows.

Due to limited length, this chapter focuses on the geographic routing techniques in a pure VANET, but it does not rule out the possibility of adopting the roadside infrastructure as a localization service. Although this chapter focuses on the routing aspect, it does not leave out the introduction of the techniques in wireless sublayers because they are the foundation of designing any routing technique.

The remainder of the chapter is organized as follows. In section 2.2, the ITS projects related to IVC are summarized. Then, we introduce the available wireless sublayer techniques that have been developed or experimented by these ITS projects. After that, we present the main sections of the chapter that explains the geographic routing techniques for VANET. In section 2.5, we present the open issues in developing an IVC technique and conclude the chapter.

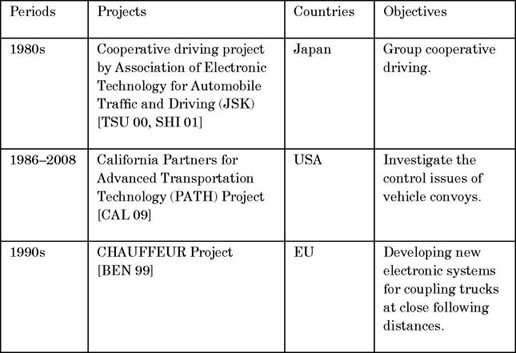

The requirements of IVC networks are different in ITS projects. The earlier ITS projects started from enabling the coordinated driving that couples vehicles at close following distances. Normally, the leading vehicle with a human driver works as a base station to perform localized controls. Vehicles use pattern recognition, radar and wireless communication to form a vehicle convoy. Some projects in this period require a localized auto-organized and high-quality real-time IVC system and the typical projects are listed in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1. Typical ITS projects in 1980s–1990s

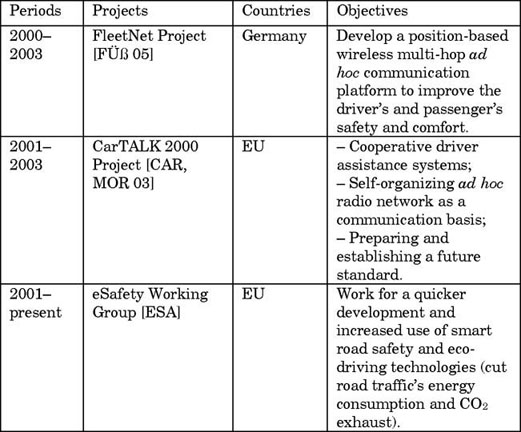

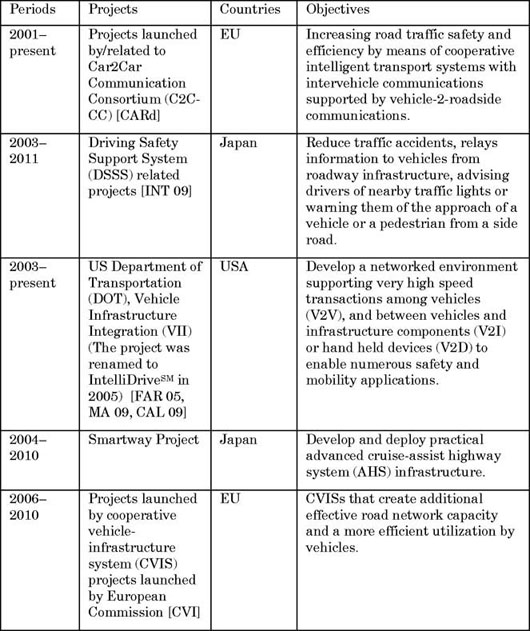

Most ITS projects in the early 2000s in Table 2.2 tried to provide the IVC-based driver assistance system because it is easier to be implemented and more flexible in complex traffic conditions. The priority of these projects is still safety and traffic efficiency, but the additional goals such as energy efficiency and driving comfort were also considered. Moreover, because the localization technology such as global positioning system/differential global positioning system (GPS/DGPS) has been relatively mature in this stage, the position-based (or called geographic) routing techniques started to be widely used in IVCs.

Table 2.2. Typical ITS projects in the early 2000s

Following the successes in the previous ITS projects, large ITS projects were starting to be launched in the mid-2000s as shown in Table 2.3. Governments, international commissions and consortiums considerably increases the investment in ITS projects, especially those relating to roadside infrastructure deployment, which is the significant difference compared with the previous period. The existing cellular towers and wireless access points were also considered being utilized as the ITS infrastructure in these projects.

Table 2.3. Typical ITS projects after mid-2000s

Although the ITS is a very active research area, most of the existing ITS projects are still in the planning and design stage. A few experiment platforms have been constructed but there will not be a large implementation until the tested systems are reliable.

The major goals of the current IVC-related ITS projects are to improve safety, traffic management, energy efficiency and driving comfort. A large part of existing IVC techniques are designed based on the assumption that a vehicle can obtain geographic information. The importance of introducing roadside infrastructure in an IVC system has been recognized by recent projects.

An IVC network connection needs to be made and authenticated very quickly in ITS applications, especially for hazard alarming and cooperative driving. Many of the current wireless techniques at the physical (PHY) layer and the media access control (MAC) layer do not fulfill the high-speed requirement. Therefore, the large ITS projects, particularly those supported by governments and international commissions, have been investigating the related technical issues. Potential solutions, especially for ITS domains, have been proposed and some of them have become standards or obtained patents. The typical PHY and MAC layers techniques that have been tested in real-world experiments are presented in this section.

The wireless local area network (WLAN) here only refers to the general Wi-Fi techniques, mainly for personal usage, because technically the dedicated short-range communication (DSRC) discussed in section 2.3.2 is also a type of WLAN technique. On the other hand, the wireless personal area network (WPAN) refers to a more specific personal network for interconnecting devices (e.g. laptops, telephones and Personal Digital Assistants (PDA)) centered on an individual person’s workspace. Although many researchers have used the WLAN and WPAN communication models in the IVC protocol designs and simulations, the major techniques that have been tested in real-world environments are only Wi-Fi (IEEE 802.11b [IEE 99]) and ZigBee (IEEE 802.15.4 [SOC 03, SOC 06]):

Both Wi-Fi and ZigBee standards work at unlicensed 2.4 GHz band, thus they eaisly get network interference or management overhead. In addition, their radio ranges are relatively shorter than DSRC discussed in section 2.3.2. However, because these techniques have been widely used in the real world and proved to be generally reliable, the ITS applications built upon them can have a lower implementation cost with a relatively high performance.

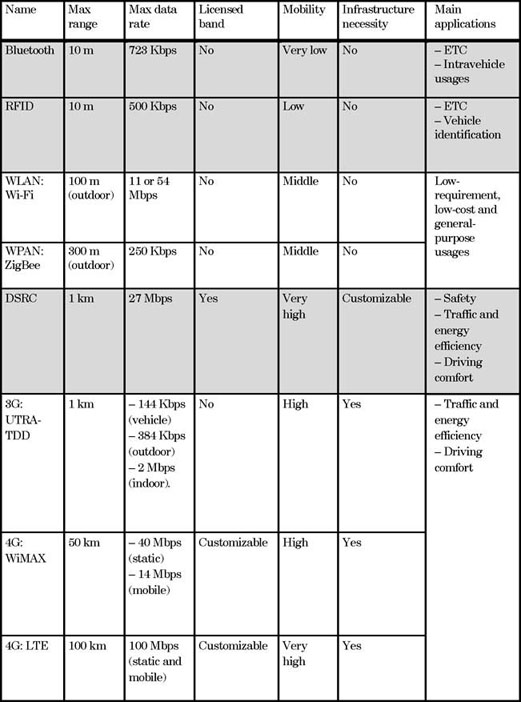

Other WPAN and WLAN techniques have been considered for adoption into ITS applications but they all have obvious drawbacks. For example, Bluetooth (IEEE 802.15.1) is also a low-cost standard in 2.4 GHz. It has a 723 Kbps data rate and up to 10 m radio range, but it only supports eight active devices and its network join time is too long (3 s). Similarly, radio-frequency identification (RFID) techniques have problems in terms of radio range and low data rate. They can be used in vehicle identification and electronic toll collection (ETC), but not for general IVC usages.

DSRC is a set of PHY and MAC techniques specifically designed for low-latency ITS solutions. The DSRC-related IEEE standard enables one-way or two-way wireless communication channels in a range up to 1,000 m with a raw data rate of up to 27 Mbps. It works on the licensed frequency band, but the frequency bands allocated for DSRC are not compatible in different countries.

Based on the works of FCC ASTM E2213-02 standard, the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) started to create working groups in 2004 to develop the standards to cover the PHY and MAC layers for ITS. The standards and the related techniques are still in the developing stage. The newest results are the IEEE 802.11p [IEE 10] specifications and IEEE 1609 family of standards [WG], which together are called wireless access in vehicular environments (WAVE).

The IEEE 802.11p standard at the MAC layer is an approved amendment to the IEEE 802.11a standard but with lower overhead operations. The MAC layer, frequency band and modulation of these two are very similar. For example, the MAC layer of WAVE also adopts CSMA/CA with an RTS/CTS mechanism. The IEEE 1609 standard family is built on top of IEEE 802.11p to add definitions and more details regarding the architecture, communications model, management structure, security mechanisms and physical access that enable low-latency mobile ad hoc and infrastructure vehicular networks.

A big research effort has been expended on adopting current cellular network techniques to support ITS applications. The main reasons are that the cellular network can provide a much longer radio range and cellular infrastructures have been used in most major cities in the world. However, cellular network techniques would normally have relatively lower data rates, longer network latencies and less reliability. Three typical cellular network techniques are given as follows:

The Universal Mobile Telecommunications System (UMTS) terrestrial radio access time division duplex (UTRA-TDD) is a 3G cellular network technique. It operates in the unlicensed frequency band from 2.010 to 2.020 GHz. It has about a 1 km radio range. The data rates are according to the speeds, such as 144 Kbps (on a moving vehicle), 384 Kbps (outdoor) and 2 Mbps (indoor). The IVC based on the development of UMTS technology can minimize the cost of the access medium, and guarantee full compatibility with the 3G mobile phone. The IVC in the FleetNet [FÜß 05] and CarTALK2000 [CAR, MOR 03] projects was developed based on the UTRA-TDD.

Regarding the forthcoming 4G techniques, worldwide interoperability for microwave access (WiMAX) and 3GPP long-term evolution (LTE) are the only two commercially used candidates:

Table 2.4 presents a comparison of the wireless sublayer techniques that are available for current or near future IVC/ITS. There are techniques that have not been presented because they either have obvious drawbacks for IVC (e.g. Bluetooth and RFID), or they are perhaps too advanced for the current technique conditions (e.g. satellite networks), or they have not been properly tested in real-world ITS test environments (lots of them).

All of the above-mentioned wireless sublayer techniques have advantages and disadvantages depending on the type of ITS application and the size of the budget. DSRC is especially designed for all ranges of ITS applications, thus normally it will have a better performance. But it is a network technique still in the development stage. However, if it is for an IVC/ITS project with small budget and tight time limit, it is more reasonable to utilize the available techniques such as Wi-Fi, ZigBee and 3G, and sometimes it may be the only choice.

Table 2.4. Comparison of considerable wireless sublayer techniques

This section presents the geographic routing techniques dedicated to the VANET in IVC/ITS applications. First, we discuss the features of VANET by comparing it with the regular MANETs in section 2.4.1. Then, we address one of the main issues in geographic routing, the localization service, in section 2.4.2. Many related chapters just assume this service is already there, but that is not practical in real-world IVC/ITS applications. After that, we present three groups of major geographic routing techniques in VANET including the classical unicast greedy routing in section 2.4.3, the geocast (multicast) routing in section 2.4.4, the delay tolerant network (DTN) based routing in section 2.4.5 and the map-based routing in section 2.4.6.

The VANET is a specific MANET. Compared with the general-purpose MANET, they have three major differences as follows:

Because of the low-mobility random pattern and small-scale features, a MANET routing would more often identify nodes by traditional IP methods, and require an end-to-end route to be found before a data delivery. The route discovery normally uses link status as a metric to obtain the best route in a weighted graph. Then, it maintains the weighted graph to adapt to topology changes. But as for a VANET routing, it is a different case. An end-to-end route could often be unavailable in a VANET. The maintenance of traditional IP and route could be very difficult. Simulations [WAN 07, MUS 10] and real-world experiments [WAN 05] also prove the incompatibility of using MANET techniques in a VANET. Therefore, a specialized routing technique needs to be developed.

By considering the VANET and IVC features, and the extra supports from localization service and roadside infrastructure, a geographic routing can be well adapted to ITS applications. The geographic routing techniques consider the physical position of nodes (or regions) as a principle routing parameter. But just to be clear, the geographic routing is not a completely new species in routing techniques. The major difference is just that it utilizes the geographic parameter in the IP and routing processes. Some principles and strategies originally proposed by MANET routing techniques can be transformed into a geographic routing, such as the loop-free mechanism in destination-sequenced distance-vector (DSDV) Routing [PER 94], the reactive and redundancy-free mechanism in ad hoc on-demand distance vector (AODV) Routing [PER 97, PER 03], the source routing in dynamic source routing (DSR) [JOH 01], the link-reversal algorithm in temporally-ordered routing algorithm (TORA) [PAR 97] and the zone-based (or cluster-based) mechanism in zone routing protocol (ZRP) [HAA 01]. But in this chapter, these non-geographic routing techniques will not be specifically discussed.

Although the geographic routing techniques have their advantages, they have not yet been become broadly practical in the IVC/ITS projects. Some problems have to be overcome first and these problems are discussed in the following sections.

The first step of a geographic routing is localization, which is one of the main challenges in using geographic routing. Although the satellite-based navigation systems such as GPS (United States), Galileo (European Union) and Beidou (China) are becoming widely available, not all vehicles can have one. Besides, because of the inadequate satellite number (e.g. blocked by buildings), the position may not be always accurate. The localization problems may be improved if a node can gain the supports from the roadside localization service, but some of them could be too expensive to be implemented. Besides, a practical localization service could meet a “the chicken or the egg” dilemma: to improve quality, a practical localization service may require a geographic routing technique to transmit some reference data in the first place. But to transmit the data, a geographic routing may need to acquire the correct geographic information from a localization service in the first place. However, many civil localization services and related techniques have been developed to solve the problems. While some of the localization techniques are relatively mature, it is reasonable to develop the VANET routing techniques based on geographic information.

Geographic routing techniques normally require a networking node to have three types of positions: its own position, the neighbor position and the destination position. Each of them has the related techniques to obtain.

Boukerche et al. [BOU 08] summarize the civil localization services that can help a node to obtain its own position.

A bigger portion of them relies on the infrastructure supports. The DGPS, video/cam localization and indoor infrastructure assist can provide a more accurate position than others, but they rely on centralized approaches to be realized. The dead reckoning can be independently completed by a node, but it is not accurate for a longer distance.

The positions of neighbor nodes are normally learned through the periodical one-hop broadcast or the reactive neighbor knowledge querying, thus this step is relatively simple. Moreover, if using a contention-based forwarding strategy, there is no need to obtain the neighbor positions in advance.

The main issue here is how to discover the destination position. Normally, the position of the destination node (or region) is specified in the forwarding packets from a source node (original sender). In the best case (e.g. the destination position is a fixed roadside infrastructure), the source node can just obtain the position directly from the roadside infrastructure. In the worst cases, the source node uses the reactive simple flooding to query the destination position from all networking nodes that it can reach. Between these two cases, two localization techniques can be adopted, namely flooding-based localization and update and query localization. Sections 2.4.2.1 and 2.4.2.2 give more details about the two localization techniques, and we summarize them in section 2.4.2.3.

Distance routing effect algorithm for mobility (DREAM) [BAS 98] represents a typical example of using the proactive flooding-based techniques: a node maintains a position table for the nodes that it can hear, and it tries to send its position-related information to the nodes that it can reach.

To control the localization overhead in flooding, the DREAM protocol considers two effects between nodes: mobility and distance. The mobility effect is implemented as the flooding frequency. The node with a higher speed floods more frequently. The distance effect refers to the phenomena that if the distance between two nodes is greater, the relative movement to each other appears to be slower (e.g. for the node A, in effect, the node B seems moving slower than node C in the southerly direction). The packet to deliver the position-related information contains node ID, position, direction and age (i.e. hop number). The age represents the result of the distance effect. The receivers of such packet can then calculate their distance effect, and decide whether to discard the packet based on the age in the packet.

Figure 2.2. An example to show the distance effect in DREAM

Another variation of flooding-based localization technique is used in location-aided routing (LAR) [KO 00a]. When nodes do not have any knowledge about the network, LAR works similarly to DSR and AODV: reactive request process, avoiding redundant requests in a flooding and the information about route and location is contained in the packets.

Note that both DREAM and LAR only use flooding in the destination discovery, not for the data delivery. More details about their data delivery techniques are given in section 2.4.4.1.

There are two major processes in update and query localization techniques: location update and destination query. The former sends out the position-related information to a subset of nodes called the location server; the latter searches the location servers to get a destination location.

The update and query localization techniques can be divided into three groups based on the differences in their localization strategies, namely hierarchical [LI 00], quorum-based [LIU 07] and home region [STO 99, RAT 02] localizations. Here, we only introduce the first two techniques, because normally the home region localization is only used in regular MANETs and wireless sensor networks (WSNs).

The hierarchical localization (or hierarchical hashing-based quorum-based localization) normally explicitly divides nodes into a hierarchical layer structure based on the node positions, and at least a node in each layer acts as a location server that responds to updates and queries for the nodes. The hierarchical localization services can help to reduce the localization overhead and achieve the network scalability, but whether it is robust enough for nodes’ mobility like VANETs will need more evaluations to be able to prove. Here, we only introduce a typical protocol called the grid localization service (GLS) [LI 00], which has the characters that are suitable for VANETs.

The GLS protocol provides a decentralized hierarchical algorithm, which can handle low-mobility nodes with a lower localization overhead. If all nodes know their GPS positions and they agree on a global origin of the hierarchy as shown in Figure 2.3, the algorithm of GLS can be done by the nodes themselves. Besides, it is possible to further introduce the fuzzy localization into the hashing function, thus not all nodes need to know their accurate GPS positions.

The layer in GLS is referred to as an order-n square. A number of order-n squares make up an order-n+1 square as the next layer, and so on. The nodes in the same square must be in each other’s one-hop communication distance, and the maximum communication distance is assumed to be two hops. Note that the location update and destination query service does not completely rely on the rules for geographic division.

For the location update (e.g. the node 8), each node periodically delivers its ID to all one-hop neighbors in its first-order square (e.g. to node 20). Then, the location is delivered to the assigned location servers in the next layer (e.g. node 1, 11, 16; maybe delivers from 59 to 16 but it is not important for the algorithm), and the process continues until the ID is delivered to the assigned location servers in all layers (e.g. node 12, 18, 36, then node 9, 10, 53). For each square in the next layers, only one location server will be assigned. The assigned location server is the node with the least ID greater (or greatest ID less) than the ID of the source node; in other words, the node with the closest ID is chosen. For the destination query, it uses a similar process, which tries to find the location server with the closest ID to the destination ID from its layer to the next ones (e.g. node 62 to 12, then 10), and a location server that has stored the ID of the destination will be found eventually.

The GLS protocol optimises the localization overhead by decentralizing the assigning of location servers. Moreover, because the GLS protocol delivers the location update and destination query based on layers, the localization overhead can be greatly reduced and it is predictable: if the height of the hierarchy is O(log(N)), effectively the location update and destination query is delivered to O(log(N)) location servers, where N is the number of nodes.

The quorum-based approach means that all nodes in the network agree upon a mapping that maps their unique identifier to one or more quorums. The quorums respond to the specified functions of other nodes.

Figure 2.3. An example of GLS localization

For quorum-based localization, it normally means that nodes send location updates to a subset of nodes (i.e. location servers), and send destination query to another subset of nodes. These two subsets of nodes must have the intersection nodes to assure a virtual connection backbone. In other cases, if two subsets of nodes are identical, they can also be called rendezvous based [FRI 06].

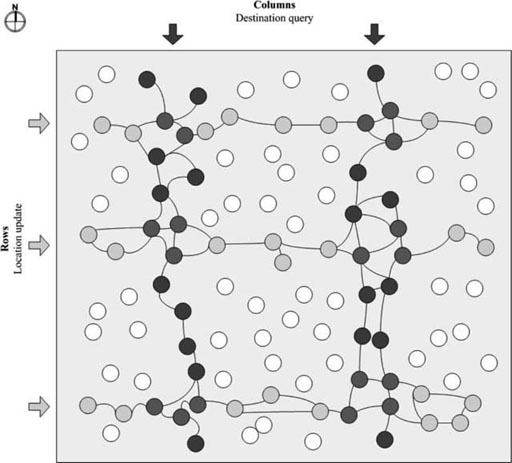

Here, we only introduce the classical quorum-based localization called column–row localization such as in dominating set quorum (DS-quorum) [LIU 07] or Column-Row Location Service (XYLS) [DAS 05]. The DS-quorum protocol proposes an algorithm that divides a network into connected dominating sets as shown in Figure 2.4. The dominating set of a graph G = (V,E) is the subset D of V, where the set of vertices in G is either in D or adjacent to a vertex in D. The nodes representing the location servers are arranged in a form of columns and rows, for example the location servers in rows may respond to the location update and the location servers in columns may respond destination query. Then, the location update is delivered from the current location of sender to north and south, until reaching the location servers in rows. The destination query is delivered from the current location of sender to east and west, until crossing the location servers in columns, and then passes to the intersection nodes with the queried location updates. Because the DS-quorum network delivers in column–row form, effectively the location update and destination query are delivered to  location servers.

location servers.

As for being used in VANETs, there are three advantages of the column–row quorum-based localizations. First, they adapt well to synchronous vehicle movements on roads; second, they can be used to form a network backbone for mixing ad hoc and infrastructure communications; third, they are able to better utilize the GPS information about longitudes (columns) and latitudes (rows).

Figure 2.4. An example of DS-quorum localization

In summary, the flooding-based localization could generate a high localization overhead and does not scale well, but they can have a low implementation complexity, and they are relatively robust in a small network section of a VANET (e.g. the short ad hoc sections between cities). On the other hand, the update and query localization can achieve the network scalability which is suitable for a large-scale VANET, but these algorithms themselves may have too much impact on localization overhead, and they are more easily affected by node failures.

The early unicast strategies started in the late 1980s are all based on a greedy forwarding strategy. The basic greedy strategies in section 2.4.3.1 select a next forwarder from neighbor nodes by measuring the maximum forwarding progress toward the destination position.

However, only using greedy forwarding will meet a void area situation, where there is no other node that is closer to the destination position than the forwarding node itself. The basic greedy forwarding will fail in this situation even if there is an existing end-to-end route to the void area.

The void area situation could happen frequently in VANETs, because the vehicles will not be distributed evenly following the shapes of roads. The situation could be more serious if considering the non-typical VANET sublayers such as Wi-Fi and ZigBee that only have radio range within 100 and 300 m, respectively. Therefore, a series of recovery solutions have been purposed and we present them in section 2.4.3.2.

Here, we can assume that the positions of a node itself and destination are known from one of the localization services. A geographic greedy routing will then forward a packet to one or more next-hop nodes with the maximum forwarding progress.

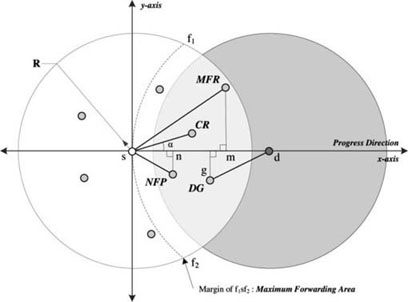

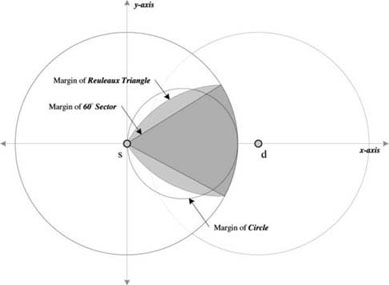

A geographic next-hop selection algorithm is normally defined in a Cartesian coordinate plane in two dimensions as in Figure 2.5. The network model is assumed to be the unit disk graph where nodes can communicate within radio range R. The node at s is the last sender and the node at d is the destination. From point s to d, it is called progress direction.

The area within the radio range and from the y-axis toward the progress direction is called progress area. An algorithm can also select the next hop in a smaller progress area, that is the maximum forwarding area with a margin in the form of an arc having the center at d. The algorithms are given as follows:

Figure 2.5. Next-hop candidates in unicast greedy forwarding

The original NFP and CR have the problem of routing loop, but MFR and DG are loop free [STO 01]. A routing-loop problem causes a packet to circulate among certain nodes.

A beacon-based forwarding requires knowing the positions of one-hop neighbor nodes, which can be achieved by neighbor knowledge exchanges (i.e. beacon exchanges). When the neighbor positions have been achieved, the selection process for the next-hop node is done by the sender itself. The beacon-based forwarding has less implementation complexity, but it relies on a wireless sublayer to provide a one-hop unicast mechanism, which is available for Wi-Fi, ZigBee and DSRC in section 2.3. The neighbor knowledge exchange could cause additional routing overhead, but it can be reduced if the frequency is well controlled.

A contention-based forwarding does not rely on neighbor knowledge exchanges. A sender may blindly broadcast a packet, then the nodes that receive the packet self-configure if they can be the next-hop forwarders. To minimize the packet collision, the number of forwarders needs to be limited by three restrictions as follows:

, where a is the parameter to adjust the advance progress and MaxDelay is the maximum delay to keep a packet before dropping it.

, where a is the parameter to adjust the advance progress and MaxDelay is the maximum delay to keep a packet before dropping it.If an RTS/CTS mechanism is available such as the Wi-Fi and DSRC based on IEEE 802.11, the second restriction is optional. A greater involved forwarding area in the progress area can exploit more candidate options such as in [ZOR 03, CHE 07].

For an implementation without an RTS/CTS mechanism such as ZigBee, there are three restriction areas, shown in Figure 2.6, proposed in beacon-less routing (BLR) [HEI 04]: a circle with the diameter equal to the radio range R, a Reuleaux triangle with the maximum apex angle of 60º or a sector with the same angle. Comparing their proportion with the area of radio range circle one, they can limit the forwarding area to the ratio of about 0.25, 0.22 and 0.17, respectively. A lesser involved forwarding area can reduce the possibility of packet collision. For example, the Implicit Geographic Forwarding (IGF) [BLU 03] based on BLR implements the sector area as the additional RTS/CTS mechanism in IEEE 802.11.

Figure 2.6. Optional areas in contention-based forwarding

If the progress area of a sender is a void, the forwarding packet will be blocked. The recovery solutions in this case work with the greedy forwarding to deliver the packet. We give more details on the major one, perimeter routing, in section 2.4.3.2.1, and then brief the others in section 2.4.3.3.

The perimeter routing can provide the best recovery solution. Although its performance relies on an ideal network condition, it can guarantee the packet delivery by only requiring the one-hop neighbor information (if an end-to-end route does exist). Besides, it can work on both beacon-based and contention-based networks.

Perimeter routing is a recovery solution based on a planar graph, which is a type of graph with edges that intersect only at their end points. A graph representing a wireless network does not naturally form as a planar graph, thus the graph needs to be simplified by a planarization process. A non-planar graph reduces the performance of a perimeter routing, and it may cause the routing-loop problem [KIM 05, LEE 10a]. The challenge for the planarization in real-world wireless networks is that the nodes can only know the one-hop neighbor information, thus a full planarization for the whole graph is not practical.

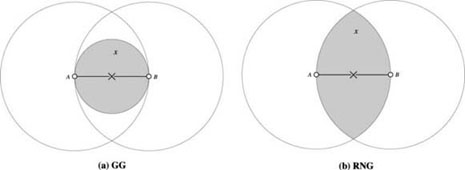

Two notable planarization algorithms that require only the one-hop neighbor information are the Gabriel graph (GG) [GAB 69] and relative neighborhood graph (RNG) [TOU 80]. For both algorithms, if any node x exists within the neighborhood ranges of both A and B (the areas with gray color as shown in Figure 2.7), the edge of (A, B) is removed to avoid the possible crossing edge, and so the remaining edges are (A, x) and (x, B).

Figure 2.7. Planarization areas of GG and RNG (in gray color)

GG defines the neighborhood range as a circle with a diameter as the line segment (A, B). RNG defines the neighborhood range as the intersection of two circles with radius R and the circles are centered at A and B. GG and RNG offer different densities of remaining edges (wireless links). RNG produces the planar subgraph with fewer edges, thus it reduces the routing overhead; on the other hand, GG produces the planar subgraph with a better connectivity, thus it may reduce the hop number to a destination.

After the localized planarization process, the nodes obtain a local view of a planar subgraph without edges crossing each other. The next strategy of perimeter routing is to adopt the right-hand rule on traversing on the borders of the faces in the planar subgraph. The packets are forwarded face by face and progressively get closer to the destination position.

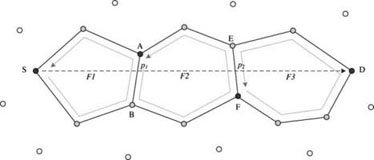

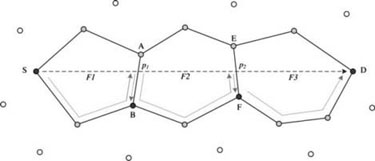

The first version of the recovery solution using perimeter routing is proposed in [BOS 99], which includes two routing algorithms called FACE-1 and FACE-2. Both FACE-1 and FACE-2 algorithms are not very efficient on their own, but they can guarantee the packet delivery. Thus, they work as the recovery solutions to incorporate with the basic greedy forwarding. Figures 2.8 and 2.9 demonstrate them as the stand-alone routing process without returning to greedy forwarding. The packet in both figures is assumed to be sent from the source node S to the destination node D by a sequence of faces (e.g. from F1 to F3).

Figure 2.8. An example of the routing path by FACE 1

Figure 2.9. An example of the routing path by FACE-2

The key rule for FACE-1 is to find the edges that intersect with the line segment from the source to the destination (e.g.  ), and the edges found (e.g. (A, B) and (E, F)) should be closer to the destination gradually (e.g. from F1 to F3, the distances dist (S, D) > dist (p1, D) > dist (p2, D)). Before a packet is passed to the next face, the packet must do a complete traversal through the border of a face and then return to the initial point (e.g. S, A or F).

), and the edges found (e.g. (A, B) and (E, F)) should be closer to the destination gradually (e.g. from F1 to F3, the distances dist (S, D) > dist (p1, D) > dist (p2, D)). Before a packet is passed to the next face, the packet must do a complete traversal through the border of a face and then return to the initial point (e.g. S, A or F).

Based on FACE-1, adaptive face routing (AFR) [KUH 02] purposed a variant algorithm. The source node in AFR initially estimates a boundary of FACE-1 as an ellipse with foci on source and destination. When a packet reaches the border of the ellipse, the packet is delivered back to the last initial point. The packet is then sent to the initial point of next face. If the routing path is blocked because the ellipse is too small, the packet is sent back to the source node, and the size of the ellipse is increased. If c is the cost of the best path in FACE-1, AFR can achieve a worst-case cost of O(c2). Besides, GOAFR+ [KUH 03] purposed an integration of the greedy forwarding and AFR.

FACE-2 is a modified version of FACE-1. When a packet is passed to the node with an edge intersecting with the line segment,  , the packet is delivered directly to the adjacent face instead of returning to the initial point (e.g. from B to F, instead of back to S). Greedy-Forward-Greedy (GFG) is a geographic routing algorithm proposed in [BOS 99], which adopts GG for planarization.

, the packet is delivered directly to the adjacent face instead of returning to the initial point (e.g. from B to F, instead of back to S). Greedy-Forward-Greedy (GFG) is a geographic routing algorithm proposed in [BOS 99], which adopts GG for planarization.

Another well-known beacon-based geographic routing protocol, called greedy perimeter stateless routing (GPSR) [KAR 00], implements a recovery solution similar to FACE-2. GPSR proposes the protocol-level details for face routing and an alternative planarization algorithm RNG. When switching faces by GPSR, the packet is always delivered through the first edge of the next face by adopting the right-hand rule. Then, the next edge is searched for in a counterclockwise direction from the last edge. The first edge must be recorded in the transmitting packet until it reaches the next face in order to avoid the routing-loop problem.

Greedy perimeter coordinator routing (GPCR) [LOC 05] is an improved version of GPSR. It utilizes the roads and streets as a communication backbone because they naturally form a planar graph. The greedy and perimeter routing in GPCR is only performed when a packet reaches the junctions. Other than that, the packet is forwarded along the road until it reaches the next junction. Therefore, GPCR is more efficient than the GPSR in an urban area.

The open issue of the recovery solutions is that they rely too much on an ideal wireless network condition, more precisely, the radio range of these solutions is assumed to be uniform as R in a unit disk graph. However, the realistic radio range is often irregular because of the differences in wireless medium densities, link errors and inaccurate positions. Some solutions were proposed for the non-ideal network conditions, for example Cross Link Detection Protocol (CLDP) [KIM 05] uses an additional proactive message for planarization and Greedy Distributed Spanning Tree Routing (GDSTR) [LEO 06] uses the traversal of a hull spanning tree (an alternative technique of planarization). However, while the former increases the routing overhead significantly, the latter loses the localizable advantage in geographic routing.

The techniques in this section can be used if a void area recovery is unavailable. There are three groups of solutions including dropping a blocked packet, sending it back or exploiting more hops in advance.

Dropping the blocked packets can be an option only if (1) the nodes are generally moving and a resend mechanism is available or (2) a multipath routing is already used so the packet is supposed to reach a destination on the other path. SPEED [HE 03] is a beacon-based solution, which considers dropping the blacked packet to reduce the traffic congestion. Each node in SPEED records the average delays to destinations in its neighboring table. When meeting a void area, the delay is marked as ∞. The neighbors then receive the notice for the void area by the so-called backpressure beacon.

Another suggestion is to send a blocked packet back to the last forwarder. The failed routing path will be marked, thus the new greedy forwarding can look for another path and avoid a routing loop. If the mobility of nodes is considered, any node in a similar position to that of the last forwarder can be used as a backtracking node. Furthermore, GDSTR [LEO 06] maintains a spanning tree where each node has an associated convex hull that contains within it the locations of all its descendant nodes in the tree. When a void area is found, the block packets are routed upwards in the tree until a node whose convex hull contains the destination is found.

In a beacon-based forwarding, a solution is to exploit more hops neighbor information in advance. The result in [STO 01] shows that if two-hop geographic information such as GEDIR, DIR and MFR is available for each node, the void area problem can be reduced. The trade-off for the two-hop geographic information is an additional routing overhead.

The geocast forwarding steps are similar to the contention-based forwarding, but the destination in geocast is more often a geographic cluster. If the destination is only a single node, when packets reach the border of the cluster that contains the destination node, the transmitting mode can be switched back to the unicast mode.

Moreover, the geocast forwarding steps can be assisted by two other techniques: hierarchy and flooding. The hierarchical geocast (e.g. GeoTora [KO 00b] and GeoNode [IMI 99]) forward packets cluster by cluster, thus it can reduce routing overhead and increase network scalability. However, the trade-off of these advantages is an overhead in cluster division. For a small area IVC built on IEEE 802.11-based Wi-Fi or DSRC, the cluster division could be too short-lived to be worth creating. The hierarchical geocast may only be suitable for a large area IVC based on 3G or 4G.

The following sections only describe the non-hierarchy flooding-based geocast techniques for VANETs. In this context, the geocast applications are only for distributing emergency messages, for example to deliver a collision warning to all approaching vehicles and nearby junctions. In the following, we will introduce two typical flooding-based geocast techniques in section 2.4.4.1 and then the related geocast techniques for VANETs in section 2.4.4.2.

DREAM [BAS 98] and LAR [KO 00a] are two broadly adopted geocast protocols. They both adopt the restricted directional flooding in their data transmission, but their restricted areas are different.

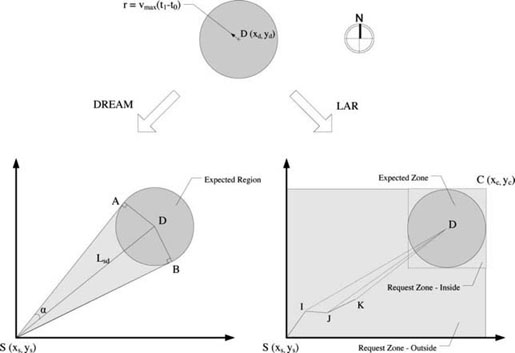

After the localization steps of DREAM and LAR discussed in section 2.4.2.1, assuming a source node S in DREAM or LAR know that the destination node D is in the position (xd, yd) at time t0, and that the current time is t1, the node can then restrict the direction and area of the next flooding as shown in Figure 2.10. The key scheme for both protocols is to ensure that a packet is sent to an expected region and that the destination node will be there when the packet reaches the expected region.

Figure 2.10. Flooding areas in DREAM and LAR

Both DREAM and LAR expect the node D to be in the circle area centered at (xd, yd) with the radius of r = vmax(t1 − t0) (e.g. the expected region (zone) are the same circle areas in the northeast from node S), but the next steps are different.

Two earlier examples of flooding-based VANET geocast protocols are the geocast scheme in [BRI 00] and the IVG in [BAC 03]. The basic strategies of them are similar.

In addition, there are other geocast algorithms and protocols for VANETs similar to these two earlier examples but with unique features.

DTN is an extreme case of MANET. VANET can be treated as a form of DTN. The distinguished feature of DTN is that the end-to-end connectivity between the source and destination in DTN is assumed to be frequently broken due to network partitioning.

The earliest research on DTN routing mostly uses the flooding-based techniques, but a more recent research direction tries to utilize the movement feature of nodes instead of adapting to it. That is why the recent DTN techniques are very suitable for VANETs.

This section provides two interesting DTN-based routing options that utilize the movement feature in VANETs: last encounter routing (LER) [GRO 03, GRO 06] and carry-and-forward routing [DAV 01].

An example of LER is a routing algorithm called exponential age search (EASE) [GRO 03, GRO 06]. The recent application of LER is in the FleetNet project, which tries to build a virtual flea market over VANET. The customers express their demands/offers by smart phones, PDAs and laptops within a VANET.

Grossglauser and Vetterli [GRO 03] first proposed a movement-based localization service, and it shows that it is possible to only use the node mobility to disseminate destination location information without using any flooding-based method. In other words, only “free” information about the local connectivity to neighboring nodes is adopted. Then, a simple routing algorithm called EASE was proposed to evaluate such localization service. The interesting conclusion about EASE is that the collections of last encounter histories at network nodes contain enough information for a geographic routing protocol to route packets.

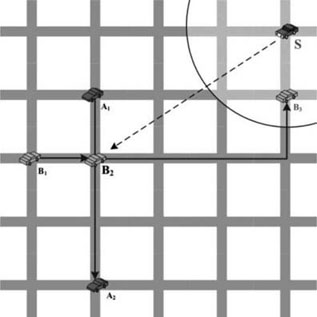

For the part of localization service, each node in EASE maintains a last encounter table (LET), which contains three fields including node ID, location and time. If a node i meets a node j at position Pij, node i records an entry as node ID equaling j and location equaling Pij. Time for the entry is the time elapsed since the encounter at Pij.

As for the routing part, the principal steps are as follows: when a source node tries to send a packet, the source node search its neighbors until finding a neighbor who meets the destination in the latest time based on the information of LET. Then, the packet is routed toward the latest encounter location. The process continues until the packet reaches the destination node. For example, vehicle S tries to send a packet to vehicle A as shown in Figure 2.11. In its current radio range, vehicle B meets vehicle A at the location of B2. If the location B2 available on B is newer than any other location information that the vehicle S can obtain, the packet is sent to the location B2. The EASE made no assumptions about how to route the packet toward a latest encounter location, and any geographic routing protocol can be used here. The disadvantage of EASE is the delivery fails easily in a practical network when the network just starts up, or where there is limited radio range, thus the number of neighbors is too small.

Figure 2.11. An example of the routing path by EASE

Carry-and-forward is a new concept proposed in [DAV 01]. The idea is as the name suggests: when a routing path does not exist for a packet, the last receiver can carry the packet and forward the packet to the new receiver until some conditions meet.

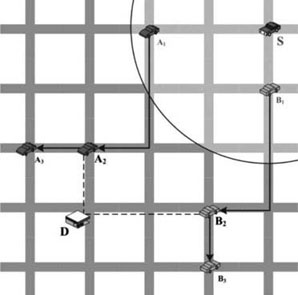

An example protocol adopting the carry-and-forward concept is vehicle-assisted data delivery (VADD) [ZHA 06]. A moving vehicle in VADD carries a packet and forwards it to the next vehicle in the intersection of roads. In other words, the routing paths in VADD are the exact shape of the roads. Moreover, VADD predicts the mobility of other vehicles, which follows the traffic pattern and road layout. A routing decision is based on the result of such a prediction. The experimented routing decisions are based on location (L-VADD), direction (D-VADD), multipath direction (MD-VADD) and hybrid (H-VADD). The H-VADD protocol has much better performance and it can avoid the routing-loop problem.

Figure 2.12. An example of the routing path by GeOpps

Geographical opportunistic routing (GeOpps) [LEO 07] is another carry-and-forward protocol, which requires navigation information of other vehicles to predict the mobility of other vehicles. By knowing the navigation information, the node in GeOpps knows the paths of other vehicles when it tries to forward a packet, then a decision can be made by comparing the nearest point of these path to the destination point. For example, vehicle S in Figure 2.12 tries to find a routing path to the gas station at D. Two vehicles, A and B, are in the radio range of S, and they will be driven from A1 to A3 and from B1 to B3, respectively. The nearest point of these two routing path is A2, thus A becomes the new relay in the routing path. The GeOpps in theory can get a better result than VADD, but the navigation information utilized in GeOpps is mostly private in VANETs.

Maybe we can call the map-based routing a semi-geographic VANET technique. This technique does not directly use the hop-to-hop querying and forwarding as in previous sections; instead, it uses a global road map provided by roadside infrastructure for calculating the shortest path. Because the map-based routing relies heavily on the supports from roadside infrastructure, it is not really a pure VANET routing technique. Here, we provide a brief because this technique can be very practical in a metropolis area. Moreover, the simulation results [LEE 10b, MUS 10] show that the map-based technique can significantly outperform the techniques without using road map.

Geographic source routing (GSR) [LOC 03] is a typical example. It uses a reactive location service (RLS), which has some similarity with the localization service in DREAM but in a reactive approach, to obtain the destination position. Then, it calculates the junctions in the road map that will be used in traversal by using the Dijkstra’s shortest path algorithm in a weighted graph, where the vertices are junctions and the edges are streets. The forwarding process between junctions is position-based.

Because the GSR only uses a static road map for its calculation, the obtained route may be a road without enough passing vehicles to be forwarding nodes. Anchor-based street and traffic aware routing (A-STAR) [LIU 04] improves the GSR by adding a traffic awareness process, which utilizes the city bus paths as an overlay map in order to identify the truck roads with higher connectivity.

It is still ongoing work for many research projects to develop a reliable IVC for ITS applications to fulfill the requirements of safety, traffic management, energy efficiency and driving comfort. It is really a difficult task because of three unique features of vehicular network: high mobility, large scale and variable density. Great research efforts have been put in this area by the schools, governments and consortiums. Although there are many potential solutions, the practical solution has not yet been found.

This chapter is mainly about the routing techniques in IVC/ITS applications, and we focus more on introducing the practical VANET routing techniques that can be used currently or in the near future. The wireless sublayer techniques on PHY and MAC are also presented in this chapter, because they are the foundations for building any practical routing technique.

The main body of the chapter gives a comprehensive survey on variant geographic routing techniques, because by considering the development of localization services, the geographic routing is quite clearly the best suitable solution for IVC/ITS applications. The survey presents the main research direction in geographic routing techniques, the unicast greedy routing, with three additional or substitutable techniques including geocast, DTN-based and map-based techniques.

The chapter has introduced the main open issues and new techniques in these geographic routing techniques along with the technique in localization service, but there are still many of them that have not been fully addressed, such as the security problem in IVC/ITS, the conversion between Internet Protocol version 4 (IPv4)/Internet Protocol version 6 (IPv6) and geographic position, the location-aware transport layer techniques and the QoS problems in low-cost sublayer techniques. The research outcomes of these areas will surely improve the reliability and efficiency in IVC/ITS applications.

This work was sponsored by three organizations: the French government through the research program “Investissements d’avenir” at the IMobS3 Laboratory of Excellence (ANR-10-LABX-16-01), the European Union through the program “Regional Competitiveness and Employment” 2007–2013 (ERDF–Auvergne region), and the Auvergne region.

[AZI 03] AZIZ F.M., Implementation and Analysis of Wireless Local Area Networks for High-Mobility Telematics, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, 2003.

[BAC 03] BACHIR A., BENSLIMANE A., “A multicast protocol in ad hoc networks inter-vehicle geocast”, Proceedings of the 57th IEEE Semiannual Vehicular Technology Conference, Jeju, South Korea, 2003.

[BAS 98] BASAGNI S., et al., “A distance routing effect algorithm for mobility (DREAM)”, Proceedings of the 4th Annual ACM/IEEE International Conference on Mobile Computing and Networking, ACM, New York, NY, 1998.

[BEN 99] BENZ T., et al., CHAUFFEUR – TR 1009 – User, Safety and Operational Requirements, Community Research and Development Information Service (CORDIS), 1999.

[BLU 03] BLUM B.M., et al., IGF: A State-Free Robust Communication Protocol for Wireless Sensor Networks, Computer Science Department, University of Virginia, 2003.

[BOS 99] BOSE P., et al., “Routing with guaranteed delivery in ad hoc wireless networks”, Proceedings of the 3rd International Workshop on Discrete Algorithms and Methods for Mobile Computing and Communications, ACM, New York, NY, 1999.

[BOU 08] BOUKERCHE A., et al., “Vehicular ad hoc networks: a new challenge for localization-based systems”, Computer Communications, vol. 31, no. 12, pp. 2838–2849, 2008.

[BRI 00] BRIESEMEISTER L., et al., “Disseminating messages among highly mobile hosts based on inter-vehicle communication”, IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium, Dearborn, Michigan, USA, 2000.

[CAL 09] California PATH Annual Report, 2009. Available at http://www.path.berkeley.edu/.

[CARa] CAR 2 CAR Communication Consortium (Car2Car CC), 2013. Available at http://www.car-to-car.org/.

[CARb] CarTALK2000 Website, 2001. Available at http://www.cartalk2000.net/.

[CHE 07] CHEN D., DENG J., VARSHNEY P.K., “Selection of a forwarding area for contention-based geographic forwarding in wireless multi-hop networks”, IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology, vol. 56, no. 5, pp. 3111–3122, 2007.

[CVI] CVIS Project Website, 2009. Available at http://www.cvisproject.org/.

[DAS 05] DAS S.M., PUCHA H., HU Y.C., “Performance comparison of scalable location services for geographic ad hoc routing”, INFOCOM 2005, 24th Annual Joint Conference of the IEEE Computer and Communications Societies, Proceedings IEEE, Miami, USA, vol. 2, pp. 1228–1239, 2005.

[DAV 01] DAVIS J.A., FAGG A.H., LEVINE B.N., “Wearable computers as packet transport mechanisms in highly-partitioned ad-hoc networks”, Proceedings of the 5th IEEE International Symposium on Wearable Computers, IEEE Computer Society, Washington, DC, 2001.

[DIA 09a] DIAO X.X., et al., “Cooperative inter-vehicle communication protocol with low cost differential GPS”, Journal of Networks, vol. 4, no. 6, pp. 445–457, 2009.

[DIA 09b] DIAO X., et al., “Experiments on PAVIN platform for cooperative inter-vehicle communication protocol (CIVIC)”, IEEE Conference in Africa (AFRICON), Kenya, 2009.

[DIA 10] DIAO X.X., et al., “An embedded system dedicated to intervehicle communication applications”, Hindawi Publishing Corporation EURASIP Journal on Embedded Systems, p. 15, 2010.

[ESA] eSafety Website, 2012. Available at http://ec.europa.eu/information_society/activities/esafety/.

[FAR 05] FARRADYNE P., Vehicle Infrastructure Integration (VII) Architecture and Functional Requirements, ITS Joint Program Office, 2005.

[FCC 02] FCC, ASTM E2213-02 Standard Specification for Telecommunications and Information Exchange Between Roadside and Vehicle Systems — 5 GHz Band Dedicated Short Range Communications (DSRC) Medium Access Control (MAC) and Physical Layer (PHY) Specifications, Federal Communications Commission (FCC), 2002.

[FIN 87] FINN G.G., Routing and Addressing Problems in Large Metropolitan-Scale Internetworks, University of Southern California, Information Sciences Institute, 1987.

[FRI 06] FRIEDMAN R., KLIOT G., Location Services in Wireless Ad Hoc and Hybrid Networks: A Survey, Department of Computer Science Technion, Israel, 2006.

[FÜß 05] FÜ LER H., et al., “Position-based routing in ad-hoc wireless networks”, in FRANZ W., HARTENSTEIN H., MAUVE M. (eds), Inter-Vehicle-Communications Based on Ad Hoc Networking Principles – The FleetNet Project, Göttingen University Press, Karlsruhe, Germany. pp. 117–143, 2005.

[GAB 69] GABRIEL R.K., SOKAL R.R., “A new statistical approach to geographic variation analysis”, Systematic Zoology, vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 259–278, 1969.

[GRO 03] GROSSGLAUSER M., VETTERLI M., “Locating nodes with EASE: last encounter routing in ad hoc networks through mobility diffusion”, INFOCOM 2003, Twenty-Second Annual Joint Conference of the IEEE Computer and Communications, IEEE Societies, San Francisco vol. 3, pp. 1954–1964, 2003.

[GRO 06] GROSSGLAUSER M., VETTERLI M., “Locating mobile nodes with EASE: learning efficient routes from encounter histories alone”, IEEE/ACM Transactions on Networking, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 457–469, 2006.

[HAA 01] HAAS Z.J., PEARLMAN M.R., “The performance of query control schemes for the zone routing protocol”, IEEE/ACM Transactions on Networking, vol. 9, no. 4, pp. 427–438, 2001.

[HE 03] HE T., et al., “SPEED: a stateless protocol for real-time communication in sensor networks”, Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Distributed Computing Systems, Providence, RI, USA, 2003.

[HEI 04] HEISSENBÜTTEL M., BRAUN T., BERNOULLI T., et al., “BLR: beacon-less routing algorithm for mobile ad hoc networks”, Computer Communications, vol. 27, no. 11, pp. 1076–1086, 2004.

[HOU 86] HOU T.-C., LI V., “Transmission range control in multihop packet radio networks”, IEEE Transactions on Communications, vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 38–44, 1986.

[IEE 99] IEEE, Part 11: Wireless LAN Medium Access Control (MAC) and Physical Layer (PHY) specifications: Higher-Speed Physical Layer Extension in the 2.4 GHz Band, IEEE Computer Society, 1999 (Retrieved 2007).

[IEE 10] IEEE Standard for information technology – Telecommunications and information exchange between systems – Local and metropolitan area networks – Specific requirements Part 11: Wireless LAN Medium Access Control (MAC) and Physical Layer (PHY) Specifications – Amendment 6: Wireless Access in Vehicular Environments, 2010. Available at http://standards.ieee.org/getieee802/download/802.11p-2010.pdf.

[IMI 99] IMIELIŃSKI T., NAVAS J.C., “GPS-based geographic addressing, routing, and resource discovery”, Communications of the ACM, vol. 42, pp. 86–92, 1999.

[INT] Introductions of Driving Safety Support System (DSSS) Project, 2009. Available at http://www2.toyota.co.jp/en/news/11/06/0629.html; http://global-sei.com/sn/2009/384/3.html.

[JOH 01] JOHNSON D.B., MALTZ D.A., BROCH J., “DSR: the dynamic source routing protocol for multi-hop wireless ad hoc networks”, in PERKINS C.E. (ed.), Ad Hoc Networking, Chapter 5, Addison-Wesley, pp. 139–172, 2001.

[KAN 09] KANDARPA R., et al., Final Report: Vehicle Infrastructure Integration Proof-of-Concept Technical Description – Infrastructure, Research and Innovative Technology Administration (RITA) U.S. Department of Transportation, 2009.

[KAR 00] KARP B., KUNG H.T., “GPSR: greedy perimeter stateless routing for wireless networks”, Proceedings of the 6th Annual International Conference on Mobile Computing and Networking (MobiCom ’00), ACM, New York, NY, 2000.

[KIM 05] KIM Y.-J., et al., “Geographic routing made practical”, Proceedings of the 2nd Conference on Symposium on Networked Systems Design & Implementation, USENIX Association, Berkeley, CA, vol. 2, 2005.

[KO 00a] KO Y.-B., VAIDYA N.H., “Location-aided routing (LAR) in mobile ad hoc networks”, Wireless Networks, vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 307–321, 2000.

[KO 00b] KO Y.-B., VAIDYA N.H., “GeoTORA: a protocol for geocasting in mobile ad hoc networks”, Proceedings of the 2000 International Conference on Network Protocols, IEEE Computer Society, Washington, DC, 2000.

[KOR 04] KORKMAZ G., ÖZGÜNER F., EKICI E., et al., “Urban multi-hop broadcast protocol for inter-vehicle communication systems”, Proceedings of the 1st ACM International Workshop on Vehicular Ad Hoc Networks (VANET ’04), ACM, New York, NY, 2004.

[KRA 99] KRANAKIS E., SINGH H., URRUTIA J., “Compass routing on geometric networks”, 11th Canadian Conference on Computational Geometry, Vancouver, Canada 1999.

[KUH 02] KUHN F., WATTENHOFER R., ZOLLINGER A., “Asymptotically optimal geometric mobile ad-hoc routing”, Proceedigs of the 6th International Workshop on Discrete Algorithms and Methods for Mobile Computing and Communications, ACM, New York, NY, 2002.

[KUH 03] KUHN F., WATTENHOFER R., ZOLLINGER A., “Worst-case optimal and average-case efficient geometric ad-hoc routing”, Proceedings of the 4th ACM International Symposium on Mobile Ad Hoc Networking & Computing, ACM, New York, NY, 2003.

[LEE 10a] LEE K.C., CHENG P.-C., GERLA M., “GeoCross: a geographic routing protocol in the presence of loops in urban scenarios”, Ad Hoc Networks, vol. 8, pp. 474–488, 2010.

[LEE 10b] LEE K.C., LEE U., GERLA M., “Survey of Routing Protocols in Vehicular Ad Hoc Networks”, in Advances in Vehicular Ad-Hoc Networks: Developments and Challenges, IGI Global, 2010.

[LEO 06] LEONG B., LISKOV B., MORRIS R., “Geographic routing without planarization”, Proceedings of the 3rd Conference on 3rd Symposium on Networked Systems Design & Implementation (NSDI ’06), USENIX Association, Berkeley, CA, 2006.

[LEO 07] LEONTIADIS I., MASCOLO C., “GeOpps: geographical opportunistic routing for vehicular networks”, World of Wireless, Mobile and Multimedia Networks, 2007 (WoWMoM 2007), IEEE International Symposium on a World of Wireless, Mobile and Multimedia Networks, Helsinki, Finland, 2007.

[LI 00] LI J., et al., “A scalable location service for geographic ad hoc routing”, Proceedings of the 6th Annual International Conference on Mobile Computing and Networking (MobiCom ’00), ACM, New York, NY, 2000.

[LIU 04] LIU G., et al., “A routing strategy for metropolis vehicular communications information networking. Networking technologies for broadband and mobile networks”, in KAHNG H.-K., GOTO S., (eds), Networking Technologies for Broadband and Mobile Networks, Berlin/Heidelberg, Springer, pp. 134–143, 2004.

[LIU 07] LIU D., JIA X., STOJMENOVIC I., “Quorum and connected dominating sets based location service in wireless ad hoc, sensor and actuator networks”, Computer Communications, vol. 30, pp. 3627–3643, 2007.

[LOC 05] LOCHERT C., et al., “Geographic routing in city scenarios”, SIGMOBILE Mobile Computing and Communications Review, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 69–72, 2005.

[LOC 03] LOCHERT C., et al., “A routing strategy for vehicular ad hoc networks in city environments”, CORD Conference Proceedings, Columbus, OH, USA, pp. 156–161, 2003.

[MA 09] MA Y., et al., “Real-time highway traffic condition assessment framework using vehicle-infrastructure integration (VII) with artificial intelligence (AI)”, Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, vol. 10, pp. 615–627, 2009.

[MAI 04] MEIHÖFER C., EBERHARDT R., “Geocast in vehicular environments: caching and transmission range control for improved efficiency”, IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Parma, Italy, 2004.

[MAI 05] MAIHÖ F., CHRISTIAN L. LEINMÜ, TIM, SCHOCH E., “Abiding geocast: time–stable geocast for ad hoc networks”, Proceedings of the 2nd ACM International Workshop on Vehicular Ad Hoc Networks (VANET ’05), ACM, New York, NY, 2005.

[MOR 03] MORSINK P., et al., “CarTALK2000: development of a co-operative ADAS based on vehicle-to-vehicle communication”, 10th World Congress and Exhibition on Intelligent Transport Systems and Services, Madrid, Spain, 2003.

[MUS 10] MUSTAFA B., RAJA U.W., “Issues of routing in VANET”, School of Computing, Blekinge Institute of Technology, 2010.

[OYA 00] OYAMA S., TACHIKAWA K., SATO M. “DSRC standards and etc systems development in Japan”, Proceedings of the 7th World Congress on Intelligent Systems, Turin, Italy, 2000.

[PAR 97] PERKINS, CHARLES E. and BHAGWAT, PRAVIN, “Highly dynamic Destination-Sequenced Distance–Vector routing (DSDV) for mobile computers”, Proceedings of the Conference on Communications Architectures, Protocols and Applications, ACM, London, United Kingdom, pp. 234–244, 1994.

[PER 94] PERKINS C.E., BHAGWAT P., “Highly dynamic destination-sequenced distance-vector routing (DSDV) for mobile computers”, Proceedings of the conference on Communications architectures, protocols and applications, ACM, London, United Kingdom, pp. 234–244, 1994.

[PER 97] PERKINS C.E., Ad Hoc On-Demand Distance Vector Routing Protocol, IETF MANET Working Group, 1997.

[PER 03] PERKINS C., ROYER E., DAS S., Ad hoc On-Demand Distance Vector (AODV) Routing (Retrieved 18 May 2010), The Internet Society, 2003.

[PIO 08] PIAO J., MCDONALD M., “Advanced driver sssistance systems from autonomous to cooperative approach”, Transport Reviews, vol. 28, no. 5, pp. 659–684, 2008.

[RAT 02] RATNASAMY S., et al., “GHT: a geographic hash table for data-centric storage”, Proceedings of the 1st ACM International Workshop on Wireless Sensor Networks and Applications, ACM, New York, NY, 2002.

[SHI 01] SHIRAKI Y., et al., “Development of an inter-vehicle communications system”, Special Edition on ITS, vol. 68, pp. 11–13, 2001.

[SMA] Smartway WIKI, 2010. Available at http://wiki.fot-net.eu/index.php?title=Smartway; http://www.nilim.go.jp/.

[SOC 03] SOCIETY I.C., IEEE Std 802.15.4-2003, Part 15.4: Wireless Medium Access Control (MAC) and Physical Layer (PHY) Specifications for Low-Rate Wireless Personal Area Networks (LR-WPANs), IEEE Computer Society, New York, NY, 2003.

[SOC 06] SOCIETY I.C., IEEE Std 802.15.4-2006, Part 15.4: Wireless Medium Access Control (MAC) and Physical Layer (PHY) Specifications for Low-Rate Wireless Personal Area Networks (WPANs), IEEE Computer Society, New York, NY, 2006.

[STO 99] STOJMENOVIC I., Home Agent Based Location Update and Destination Search Schemes in Ad Hoc Wireless Networks, SITE, University of Ottawa, 1999.

[STO 01] STOJMENOVIC I., LIN X., “Loop-free hybrid single-path/flooding routing algorithms with guaranteed delivery for wireless networks”, IEEE Transactions on Parallel and Distributed Systems, vol. 12, no. 10, pp. 1023–1032, 2001.

[SUI 84] SUI H., ZEIDLER J.R., “Optimal transmission ranges for randomly distributed packet radio terminals”, IEEE Transactions on Communications, vol. 32, no. 3, pp. 246–257, 1984.

[TOU 80] TOUSSAINT G.T., “The relative neighbourhood graph of a finite planar set”, Pattern Recognition, vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 261–268, 1980.

[TSU 00] TSUGAWA S., “An introduction to demo 2000: the cooperative driving scenario”, IEEE Intelligent Systems, vol. 15, pp. 78–79, 2000.

[TSU 05] TSUGAWA S., Issues and Recent Trends in Vehicle Safety Communication Systems, LATSS Research, 2005.

[WAN 05] WANG S.Y., et al., “A practical routing protocol for vehicle-formed mobile ad hoc networks on the roads”, IEEE International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems, Vienna, Austria, 2005.

[WAN 07] WANG W., XIE F., CHATTERJEE M., “An integrated study on mobility models and scalable routing protocols in VANETs”, Proceedings in 2007 Mobile Networking for Vehicular Environments, Anchorage, Alaska, pp. 97–102, 2007.

[ZHA 06] ZHAO J., CAO G., “VADD: vehicle-assisted data delivery in vehicular ad hoc networks”, Proceedings IEEE INFOCOM 2006. 25TH IEEE International Conference on Computer Communications, IEEE, 2006.

[ZOR 03] ZORZI M., RAO R.R., “Geographic random forwarding (GeRaF) for ad hoc and sensor networks: multihop performance”, IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing, vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 337–348, 2003.

[WG] 1609 WG – Dedicated Short Range Communication Working Group, 2013. Available at http://standards.ieee.org/develop/wg/1609_WG.html.