Since their inception in 1868 outside the British Houses of Parliament in London, traffic signaling systems have been one of the major components in traffic management strategies. In general, their purpose is to regulate the vehicular flow at the intersection by managing the movements of different vehicles approaching the intersection with reference to time. Precisely, the platoon of vehicles is allowed to cross the intersection in turn, or in phases, thus making it easier and safer for drivers as well as pedestrians. The basic concepts involved in any traffic signal systems are the following:

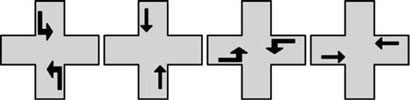

Figure 7.1. Phases of signal cycle

Most of the existing traffic signal systems work with a set of pre-timed cycles that generated off-line using the historical data of traffic demand. These systems try to match the best possible timing plan, from the existing database, for the current hour of the day. However, in recent years due to exponential increase of vehicular traffic, the traditional traffic signal control system fails to fulfill the requirements in urban areas for traffic management. Improper traffic signal control systems at the intersections are one of the major contributors for the increase in recurring traffic congestion [ABD 03]. Millions of people deal with such traffic congestion on a daily basis. Along with the effects on drivers, environment and health, such traffic congestion has shown its effect on economy as well. Within the US alone, the annual cost of congestion is estimated to be “US$ 63.1 billion”, caused by “3.7 billion hours of delays” and “8.7 billion liters of ‘wasted’ fuel” [SCH 05], whereas in European Union the congestion costs nearly 1% of the EU’s gross domestic product (GDP), annually [PRU 05]. Hence it is imperative to improve the efficiency of existing transportation facilities.

To ameliorate the traffic conditions in urban scenarios, it is important to develop dynamic traffic signal control that will adapt itself to varying vehicular traffic demand and optimize its timings accordingly. Such optimizations will result into smoother traffic flows at the intersections which will reduce the travel time for the users. This, in turn, reduces the number of vehicles that stop at the intersection and hence cuts the vehicular emissions.

To achieve this, many works have been proposed in the literature. In the following sections, a classification and description of the existing signal control methods are discussed.

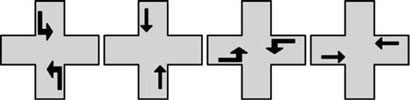

As discussed earlier, improper traffic signal controllers at the intersections are one of the factors that contribute to the degradation of the traffic flow. This drawback demonstrates the need for improvement in the functioning of traffic signal systems. Within this context, the technology of traffic signal system has evolved significantly over the years from the basic pre-timed systems to complex adaptive systems. The framework of the available solutions in traffic signal systems can broadly be classified into static systems and dynamic systems (Figure 7.2).

Figure 7.2. Classification of traffic signal systems

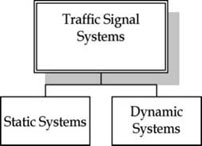

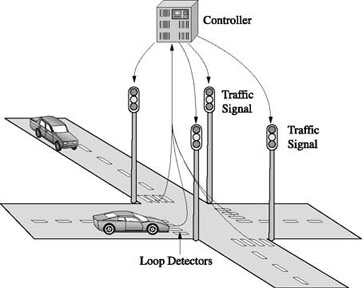

Static systems represent the most basic form of traffic signal control (Figure 7.3) and operate on a predetermined regularly repeated sequence of signal indications [SKA 04]. The signal rotates through a defined cycle in a constant fashion, as determined by the controller’s settings. For example, in one complete phase of the cycle, each street may be assigned some seconds of green time, several seconds of yellow interval and the remaining time to the red interval. This timing of static signals is typically determined from visual observations and traffic counts. Once the timing programs are set, they remain fixed until they are changed manually.

Figure 7.3. Static signal system

Static controllers are best suited for intersections where traffic volumes are predictable, stable and fairly constant. In general, static controllers are cheaper to purchase, install and maintain [GOR 96]. Their repetitive nature facilitates coordination with adjacent signals, and they are useful in areas where progression is desired. However, there is no guarantee that the system will have a plan for the existing traffic conditions. Thus, such systems fail to respond to the varying traffic demand and accommodate highly congested flow or non-recurring traffic conditions caused by accidents, weather conditions or special events [SKA 04].

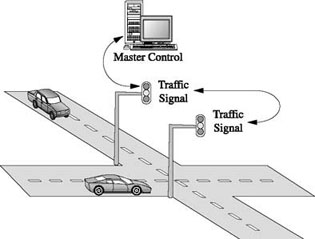

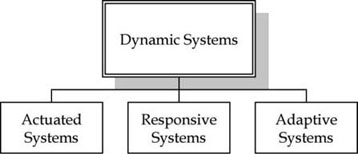

The inflexibility of fixed systems prompts for the implementation of dynamic signal systems. These systems can accommodate not only recurring traffic congestion but also adequately adjust signal timing for non-recurring traffic congestion caused by random fluctuations in traffic patterns. Such systems are termed as dynamic system (Figure 7.4).

Figure 7.4. Dynamic traffic signal systems

These systems optimize the timing plans according to the vehicular demand and help ease the congestion and its negative externalities without the cost and environmental impact of road expansion. In the literature, there are several ways, such as inductive loops or sensor, through which the existing circumstances of the vehicular traffic can be procured [GOR 96]. On the basis of the working methodology, the dynamic systems can be further classified into three classes: actuated, responsive and adaptive (Figure 7.5). Of these, adaptive systems are the most advanced and complex traffic signal systems.

Figure 7.5. Classification of dynamic systems

Vehicle-actuated controllers are the basic dynamic systems that operate in real-time by applying a control in accordance to the current traffic state. An actuated controller operates based on traffic demands as registered by the actuation of vehicle and/or pedestrian detectors. The most common method of detecting vehicles is to install inductive loop wires [GOR 96]. The main feature of actuated controllers is the ability to adjust the length of the currently active phase in response to traffic flow. In such controllers, the green time for a phase which is a function of the traffic flow can be varied between pre-timed minimum and maximum lengths depending on flows. If there are no vehicles detected on an approach, the controller skips that phase. Actuated control can be further classified into semi-actuated control and full-actuated control.

A semi-actuated controller is usually installed in places where small streets join the main road. In this, the actuator can modify all phases except the phase associated with the main road. A continuous green time is maintained on the major street, that is the main road except when a demand is registered by the minor street or the joining street detector. Later the green time returns to the major street when no vehicles are present on the minor street or when the timing limit for the green period has been reached. A semi-actuated operation is best suited for locations with low volume of minor street traffic. It may also be used to permit pedestrian crossings mid street [BRU 94].

In full-actuated control, the function of the controller is to measure traffic flow on all approaches to an intersection and make assignments of green splits in accordance with traffic demand. Full-actuated control requires placement of detectors on all approaches to the intersection. The controller’s ability to respond to traffic flow provides maximum efficiency at individual locations. This type of control is appropriate for intersections where the demand proportions from each leg of the intersection are less predictable.

Although vehicle-actuated controllers operate in realtime, they attempt no systematic optimization. Vehicle-actuated traffic light controllers are simply an enhanced version of fixed-time controller where the green light time is extended whenever there is a demand. These times are fixed prior to the maximum time limit and thus do not adapt well to varying traffic conditions. Hence there is a need for better solutions in dynamic traffic signal control.

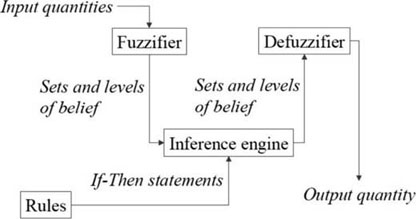

Adhering to the principles of the dynamic systems, in responsive mode the traffic signal control receives information that reflects the current traffic conditions. On the basis of this input, the system selects an appropriate timing plan from the library of different plans, which is already present in the system. In responsive systems, usually decisions about cycle timings and the splits are based on some fuzzy logic rules [VAN 06]. Typically, in a fuzzy logic controller the extension time is not a fixed value. The number of cars sensed at the input of the fuzzy controllers is converted into fuzzy values, such as low, medium and high. These fuzzy values are then compared with a defined set of rules and then the splits are allotted to different phases. Figure 7.6 depicts a basic idea of fuzzy logic system. Here, the inputs which can be various factors like the volume of traffic are processed by the fuzzifier and are then matched to corresponding rules and are given to the defuzzifier. The defuzzification unit processes the data and produces a quantifiable result, in this case the signal timings.

Figure 7.6. Fuzzy logic system

The authors [ANT 05] present a fuzzy logic based traffic signal systems where loop detectors are employed for estimating the number of vehicles on each lane. At the end of each phase these numbers are used as inputs to fuzzy controller that calculates the next signal cycle duration. At the fuzzy controller each input is represented with three membership functions corresponding to low, medium and high traffic density. Inputs processed through fuzzy controller rule to arrive at the green light duration for the forthcoming phase.

The analysis shows that real-time fuzzy logic controller for traffic lights signal durations in combination with optimized phase is an alternative to a classical fixed phase duration. However, this approach is tested only for an isolated intersection; hence it may not result into an effective green wave.

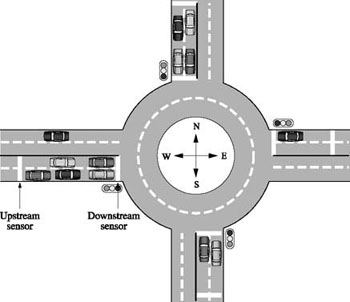

An enhancement to this approach is described in [FAH 06] where the author describes a fuzzy logic controller for a roundabout with four intersected roads. In this approach, there are two sensors placed on each incoming lane (Figure 7.7). The first sensor (downstream sensor) is at the traffic lights and counts the cars passing the traffic lights. The second sensor (upstream sensor), which is located before the first sensor, counts the cars coming to the roundabout at a given distance from the lights. The amount of cars for a roundabout lane is determined by the difference of the readings between the two sensors.

Figure 7.7. Structure of fuzzy traffic control system

Once the traffic volume is estimated the fuzzy logic controller determines which approach has the highest priority in order to give it the green light. This priority is decided by the fuzzy controller based on the following two factors: the quantity of the traffic waiting on the arrival side and the traffic waiting time.

The results show that the performance of this approach is better than the fixed-time controller, or even vehicle-actuated controllers. The reason is that it counts the number of vehicles sensed at the incoming approaches, and their waiting time then finds the winning approach for green light. Though this approach is better than the traditional systems, it has the drawback of starvation. There might be cases where only one lane gets the priority for all the cycles thus resulting in a degraded performance.

The authors [ZHA 05] propose a fuzzy logic controller to determine whether to extend or terminate the current green phase based on a set of fuzzy rules. The fuzzy rules compare traffic conditions with the current green phase and traffic conditions with the next candidate green phase.

The fuzzy logic controller determines whether to extend or terminate the current green phase after a minimum green time has expired. Once the green time is extended, after a specific time interval the fuzzy logic controller determines whether the current green time should be extended or not. This time interval may vary from 0.1 to 10 s depending on the controller’s processor speed. If the fuzzy logic controller determines to terminate the current phase, then the signal will go to the next phase. If not, the current phase will be extended and the fuzzy logic controller will make the next decision after the next time interval and so forth until the maximum green time is reached. The decision-making process is based on a set of fuzzy rules that takes into account the traffic conditions with the current and next phases. Though the performance in terms of waiting time is improved as compared to the solution proposed by [FAH 06], the system is not totally dynamic as the green time cannot be extended beyond a certain maximum time and this extension limit is also fixed. Although this helps in avoiding starvation, such hard bound limits should be avoided to make the system more efficient.

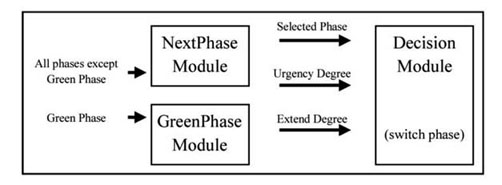

This problem is tackled in [KHA 05] where the system considers two main features: first, to reduce the total delay time of waiting vehicles as well as to avoid heavy traffic congestion, and second to synchronize the local traffic controller with its neighbors, such as controlling the outgoing vehicles into neighboring traffic controllers. In this approach, three modules are proposed in the design of the fuzzy traffic lights controller: next phase module, a green phase module and a decision module (Figure 7.8).

Figure 7.8. Modules of the proposed fuzzy logic controller

The next phase module and green phase module consider and evaluate the number of vehicles from the local detectors (detectors within the lane itself) and remote detectors (detectors from neighbor lanes). The next phase module selects the most urgent phase among all the other phases except the green phase. The green phase module observes the condition of traffic flow of the green phase only. The decision module decides the urgency degree between the next phase and the green phase modules. Thereby it can decide if the current green phase signal has to be extended or whether the passage should be given to other phases. For example, if the green phase module is more urgent than the next phase module, then the green signal will be extended. In addition, if the next phase module is more urgent than the green phase module, the decision module will change the green phase signal to another phase. As it is evident most of the systems are based on loop detectors and sensors. However, the cost of deploying loop detectors is very high [DOA 09] thus making them an expensive approach.

An improvement to these systems is provided in [WEN 08] where an RFID-based detection technique for fuzzy logic approach is described. In this an RFID reader installed at the roadside detects an RF-ACTIVE code that is present on the vehicle. This allows us to detect the inter arrival rate of the vehicles on a given road. On the basis of these reading, a fuzzy controller selects the most appropriate rule that reflects the current condition and sets the green time for that particular phase. However in this work, the tests carried out are primitive and do not allow either two-way roads or car turning. The accuracy with which the RFIDs detect the flow of vehicles is also not tested thus making it vulnerable to degradation in efficiency.

To summarize the responsive systems it is seen that they use variables which allows for flexible implementation of the systems. The responsive systems allow for fuzzy thresholds which make them suitable in highly dynamic environment, because the rule based on which they work can be easily modified. However, the gradient of variation in the volume of vehicles can be very high, hence making it difficult to estimate membership function. In addition, there can be many ways of interpreting fuzzy rules, combining the outputs of several fuzzy rules and defuzzifying the output can be time consuming which can decrease the efficiency of the system.

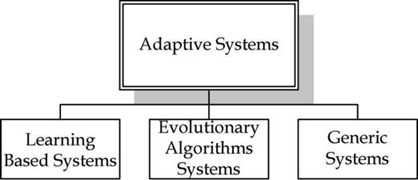

Adaptive traffic signal control systems have evolved into a potential technique for improving the traffic conditions in urban areas. They are currently the most advanced and complex dynamic control systems. They are similar to traffic responsive signals where they receive real-time data through some detectors. However, instead of matching current conditions to an existing timing plan, the system uses an optimization algorithm to create optimal signal timings in real-time. Hence, no libraries of timing plans are needed. This is advantageous for areas with high rates of growth, where libraries of timing plans have to be updated frequently. Many techniques have been developed to achieve adaptive traffic signal systems [LIU 07]. These existing adaptive systems can be divided into various approaches based on the mode they use to determine the timing plan (Figure 7.9).

Figure 7.9. Adaptive traffic signal systems

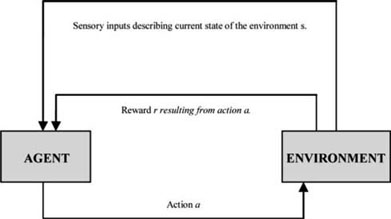

In general, learning-based algorithms are concerned with how the system should take actions to maximize some notion of long-term reward. In this case of traffic signal systems, the long-term reward is in terms of reduction in waiting time for the road users. Figure 7.10 shows the basic concept of the learning system. In this representation, the agent is the entity responsible for interpreting sensory inputs from the environment, choosing actions and learning on the basis of the effects of its actions on the environment. On the basis of its perception of the state, the agent selects an action from the set of possible actions. This decision depends on the relative value of the various possible actions. As a result of taking action in state, the agent receives a reward that depends on the effect of this action on the agent’s environment. The combination of state, action and reward is then used to update the previous estimate.

Figure 7.10. Concept of learning-based systems

One such adaptive control system based on learning algorithms is proposed by [KOO 04]. In this system, the authors develop a learning method with road-user based function to determine optimal cycles for each traffic light. This decision is based on a cumulative vote of all vehicles waiting at the intersection. For this, a value function is defined that estimates for each car the total waiting time until it has reached its destination. At the intersection the system computes the overall gain for each car if the lights were made green by traffic controller and their individual advantages are summed up.

In a similar way, the authors [GRE 07] describe an adaptive traffic light controller using intelligent agents at isolated intersections. In this system, the number of vehicle waiting near the intersection is detected through the sensors. On the basis of the number of vehicles, the idea here is to allow the agents (decision-maker at the traffic signal control) learn a traffic control policy using machine learning algorithms. This is aimed at reducing the waiting time for the vehicles at the intersection. To enable this, intelligent agents need a formal framework for decision-making. In this work, this is achieved through the use of the Markov decision processes (MDP) in the field of reinforcement learning [SUT 98]. To find the optimal solution of an MDP, the Markov property must be satisfied. This property indicates that the transition probability of reaching the next state of the traffic signal control only depends on the current state. With this property, the current state of the system encapsulates all the knowledge required in making a decision.

However, this algorithm induces high computational cost. To implement good timing patterns the agents will need to include many subtle details of the system and hence takes time to converge at the optimum timing pattern.

The authors [ELT 10] propose reinforcement-based adaptive traffic signal control with a variable phasing sequence. The authors define three evaluation functions: arrival of vehicles to the current green direction, queue length at red directions and cumulative delay. A variable phasing sequence is used to select the next action of the phase which will maximize the reward (defined as the decrease in the total cumulative delay). A greedy method [SUT 98] is used for action selection in which a greedy learner selects the action which will maximize the reward. The use of the greedy method enables the learning agent to search the overall state-action space and gradually converges to the optimal policy. The performance analysis showed that proposed approach consistently outperforms the pre-timed signal plan with a wide margin regardless of the demand level. However, since the greedy method is used to maximize the rewards, it might actually lead to starvation for a few phases approaching the intersection resulting in an inefficient system.

The authors [DUA 10] propose a new multi-objective control algorithm based on reinforcement learning for urban traffic signal control, named multi-RL. A multi-agent structure is used to describe the traffic system where vehicles are regarded as agents. A reinforcement learning algorithm is adopted to predict the overall value of the optimization objective for the given vehicles’ states. The optimization objectives include the number of vehicle stops, the average waiting time and the maximum queue length at the intersection. To make the method suitable for various traffic conditions a multi-objective control scheme is introduced. Using the optimization objectives the system allows us avoiding large-scale traffic jams and hence a better traffic flow.

Learning algorithms are truly adaptive, in the sense that they are capable of responding not only to dynamic sensory inputs from the environment, but also to a dynamically changing environment, through ongoing learning and adaptation. In general, reinforcement learning does not require a pre-specified model of the environment on which action selection is based. Instead, relationships between states, actions and rewards are learned through dynamic interaction with the environment. Another benefit of reinforcement learning, in general, is that supervision of the learning process is not required. The outcome associated with taking a particular action in any state encountered is learned through dynamic exploration of alternative actions and observation of the relative outcomes.

However, exploration of the actions and the corresponding results are necessary in the initial stages of deployment of the system, and the learning process will be incremental in nature. This procedure of gaining useful experience while exploring actions may result in non-optimal solutions, which lead to high convergence time and computation cost for an optimal solution. Moreover, a sensory subsystem is required to provide the required inputs to the agents. This may involve adaptation of the existing induction loop technology, etc. Hence any loss of communication will result in a variation of the optimal policy. Therefore, a contingency plan would also be required to deal with a potential loss of communication.

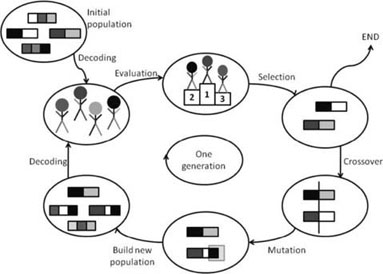

Evolutionary algorithms (EAs) are randomized optimization heuristics that mimic biological evolution to tackle optimization problems. Their general scheme is simple (Figure 7.11) which starts with a set (called population) of randomly generated initial solutions. An EA selects solutions with a relatively high quality from its population of parents, which are then combined and locally modified by crossover and mutation operators to form new offspring solutions. On the basis of their quality, some of the parents and offspring are selected to form the next generation of solutions that replaces the old population. This process is repeated until a stopping criterion is reached. Selection, crossover and mutation are randomized operations, where good solutions have a higher chance of surviving and generating offspring.

Figure 7.11. General scheme of evolutionary algorithm

EAs are widely used in many real-world optimization problems. Since the beginning of the 1990s they have also been applied to the optimization of traffic signal controls.

The research project TRAVOLUTION investigates the use of EAs for network-wide online optimizations [BRA 08]. The authors use an EA for the optimization of a signal plan that specifies the offsets, phase sequences and time frames bounding for possible phase endings. Optimization is aimed at minimizing a single-objective problem, that is the aggregate delay at the intersection. The proposed approach was evaluated in a field test at Ingolstadt, Germany. Using the EA, delays could be reduced by 21% compared to the static systems. This project is in its initial stages at the AUDI research and its being evolved into a more practical solution.

In [PRO 10], an EA is combined with a learning classifier system (LCS), a rule-based online learning mechanism, to form an adaptive learning intersection control system. While the LCS is responsible for the online selection of signal plans (based on detected traffic flows at the intersection), an EA is used to evolve necessary signal plans that are included in the LCS rule set. The study showed that delays could be reduced by 6–12%.

The simple working principle of EAs can be applied to any problem where a quality can be assigned to a solution. Therefore, the overall quality of solutions is likely to improve over time while the random influence of mutation helps to prevent premature convergence on some local optimum. Though this is an advantage, it may lead to high convergence time to an optimal solution that can hamper the efficiency in fast varying conditions.

Learning-based algorithm and EA form a broader category of methods for adaptive traffic signals control. However, there are other approaches as well which provide adaptive solutions, but they do not classify into either of the two. These solutions range from queuing theory-based to wireless system-based applications.

In [KUT 06], an adaptive algorithm is defined based on queuing theory for traffic signal control. Here an extended queue is modeled as a vector denoting the vehicles that have been waiting at the intersection. Including the mean waiting times in the model allows for a fair traffic control. The goal of the control is to find an optimal schedule for the traffic lights in the intersection, such that the difference in average waiting times between the two queues is minimized. For this, the authors apply a nonlinear model predictive controller (NMPC) [HEN 98]. NMPC allows for modifying the controller by taking into account the future incoming flow. This allows for the controller to prepare for a much better control. In addition, the use of queuing model and the use of waiting time in the state reduce the computation costs, however, it still takes time to evolve to an optimal solution.

Another mechanism of adaptive traffic signal based on constraint satisfaction (CSP) is mentioned in [MIZ 08]. Here the signal parameters, the cycle length, the split and the offset are defined as the CSP, and the optimal cycle length is determined by solving CSP with reduction in waiting time as the constraint. Precisely, the constraints are defined as:

where V is a set of variables, in which elements: cycleik, gstartik and gtimeik, correspond to time length of one cycle, start time period of the green sign in the cycle and time length of the green sign, respectively, in the kth signal belonging to the ith intersection agent; D is a set of values to be assigned to variables, where Dcycle = {40, …, 140} and Dgstart = Dgtime = {0, …, 140}. Therefore, a signal has cycle time length from 40 s to 140 s and green time length from 0 s to 140 s. C is a set of constraints composed of subsets, Cin, Cadj and Croad.

Though the simulation results show that the traffic jam is considerably reduced, but solving the CSP incurs time to arrive at an optimal solution. In addition, the length of the cycle time is bounded by preset values, hence in case of severe variation the system may fail to adapt.

To reduce the convergence time of obtaining an optimal solution, the authors [ALI 06] define a greedy control with scarcity measurement approach (GSCM). In GSCM, the control method is similar to many feedback algorithms. This feedback is quantized to a value of resource scarcity. The resource here is the streets which are to be assigned to the road users. The decision taken to set the lights green is based on the following formula:

[7.1]

Here the authors explain the price of a resource as the state of scarcity of resource and is given by:

[7.2]

where ls is the load on the street and nss is the normalized mean speed of the street and ε is set between 0 and 1.

GCSM control algorithm prohibits the control agents making worsening changes which allow us handling the traffic at the intersection in a much simpler way. However, the function has imposed two restrictions: (1) the street light changes to green in a predefined order and (2) the street green light length must be in interval of “minimum green time, maximum green time”. Such restrictions nullify the effectiveness of the system. In addition, it adapts greedy approach to select the changes that may lead to too many fluctuations if vehicular traffic undulates severely.

The rigidity and aforementioned drawback of the traditional adaptive systems prompts the exploration of a new domain to realize adaptive traffic signal controls. With recent advances in communication, computation and sensor technologies a new era of intelligent transportation using wireless communication can be envisioned. A protocol based on wireless technology is introduced in [HUA 04]. In this, the authors propose a concept of smart intersection using wireless communication. Each car sends its information, such as speed and distance to the intersection, to the traffic signal. Using this information, traffic signal control sends the decision if a car can pass the intersection or not. On the basis of this response, the car adjusts its speed so that it can reduce the waiting time at the intersection. This method aids arrival at optimal decisions in a decentralized manner, because each vehicle decides on its approaching speed to the intersection. It is thus facilitated for a faster convergence but it is prone to failure of data communication which may cause the whole system to collapse.

Although the domain of wireless communications is in its primitive stages, the work mentioned by [HUA 04] provides the impetus to investigate the domain of wireless technologies for adaptive traffic control systems. Accordingly, the authors [ZHO 10] investigate the problem of adaptive traffic light control using real-time traffic information collected by a wireless sensor network (WSN). The authors propose an adaptive traffic light control algorithm that adjusts both the sequence and length of traffic lights in accordance with the real-time traffic detected. The algorithm considers a number of traffic factors, such as traffic volume, waiting time, to determine green light sequence and the optimal green light length. The green light length is based on the different weights assigned to traffic volume, average waiting time, hunger level, blank circumstance, special circumstance and influence from neighboring intersections. The use of blank circumstances allows for fine tuning the green time so that when a blank situation approaches the intersection it is dealt with a red timing. However, the green time distribution is also based on hunger level, which indicates how much traffic is on an approaching lane. This factor can influence starvation because the less dense roads may be totally deprived of green time.

Along with sensor networks, vehicular networks also form a capable solution. The authors [GRA 07] defined one proposed solution where one-hop car-to-car communications are used for implementing the traffic controls. The authors use the solution implemented in TrafficView [NAD 04], wherein the vehicles exchange the information about the position and the speed among themselves. This enables each individual vehicle to view and assess the traffic and road condition in front of it. To achieve data dissemination the diffusion mechanism is utilized where each vehicle broadcasts information about itself and the other vehicles it knows about. Whenever a vehicle receives broadcast information, it updates its stored information and defers forwarding the information to the next broadcast period, at which time it broadcasts its updated information. During this exchange, the traffic signals listen to the communication between cars and estimate the density of vehicles around it and adjust the signal timings accordingly. The results show that the system significantly improves traffic fluency, compared to the existing pre-timed traffic lights.

As discussed in previous sections, to efficiently implement adaptive traffic control systems, we must take into account a wide range of variables, such as traffic volume, time of the day, the effects on other roads and the involvement of pedestrian traffic. In this context, vehicular ad hoc networks (VANETs) can be quite effective in estimating the volume of the traffic approaching the intersection. One of the methods called the car–car based adaptive traffic control system (CATS) is discussed in [MAS 12]. To accomplish this through VANETs, it is essential to have an effective data dissemination strategy. In the proposed approach, a cluster-based data dissemination protocol called clustering based on direction in vehicular environment (C-DRIVE) [MAS 11]. Performance evaluation of the system shows that the average waiting time is considerably reduced compared to the fuzzy logic and pre-timed systems. In terms of efficiency, as shown in Figure 7.11, it is found that CATS reduces the number of vehicles that stop at the intersection by almost 20%. The encouraging results show that adaptive traffic lights based on car-to-car communication has a good potential for improving the traffic conditions in urban areas.

Traffic signal systems are an important element to improve the traffic flow in urban scenarios. Their basic aim is to regulate the traffic at intersections. Along with facilitating a smooth traffic flow that will save a lot of time and fuel for road users, traffic lights also help in reducing the number of accidents. Traditional traffic signal systems work in a pre-timed manner in which the cycle timings are preset. Such rigidity does not work well in the fast-growing urban scenarios. The need of the hour, in fast varying traffic conditions, is to provide systems that can change their cycle timings dynamically.

With this objective much work has been done in this area where signal timings dynamically adjust to the traffic demand. The various dynamic systems can be classified into three major categories: actuated, responsive and adaptive systems. Adaptive are the most complex and advanced systems. They can be further classified into learning based, EAs and generic methods. Most of the works mentioned in generic methods are based on the use of wireless communications. As compared to the traditional pre-timed systems the dynamic systems help in improving the traffic conditions at the intersections. Precisely, dynamic systems improve the responsiveness of signal timing in rapidly changing traffic conditions. Various works have demonstrated network performance enhancement from 5% to over 30% in the user waiting time at the intersection.

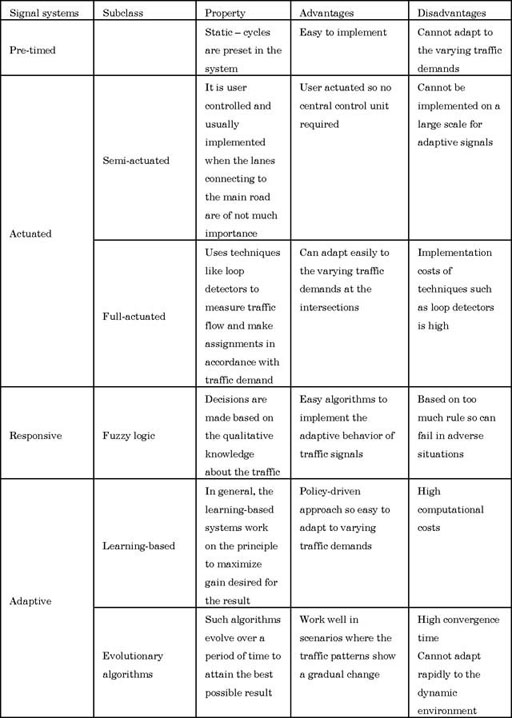

Though various methods defined under dynamic systems show improvement in the traffic efficiency, they still leave a lot of scope for development. Table 7.1 gives a brief summary of the classification along their advantages and disadvantages.

Apart from the implementation issues two factors, namely average waiting time and reduction in queue length form the basis on which the performance of the dynamic system is evaluated. Here, queue length represents the number of vehicles that stops at the intersection when they encounter a red light. The average waiting time factor presents the delay experienced by the vehicles that stops at the intersection. Table 7.2 provides a comparative analysis for various dynamic systems in terms of these two factors.

Table 7.1. Summary of traffic signal control systems

Table 7.2. Comparison of dynamic systems

| Dynamic systems | Effect on average waiting time and queue length |

| Actuated | Since they are extension of pre-timed systems, waiting time can be reduced to an extent only for recurring traffic congestion. This is achieved by extending green time to a certain limit. The queue length can be controlled for recurring traffic congestions, but it tends to increase exponentially for non-recurring and volatile traffic conditions. |

| Responsive | In this mode, the system selects an appropriate timing plan from the library of different plans which are already present in the system. Hence, the waiting time and the queue length will be reduced only if exact criteria reflecting the traffic conditions are found. |

| Learning-based | In learning-based systems, the waiting time can be reduced only after the systems stabilize to an optimum output. However, to arrive at stability point it takes time and hence the average gain in terms of waiting time and reduction in queue length is limited during the initial phase. Even after the stable state, if the traffic conditions change the system reinitiates the learning process thus incurring more computational costs. |

| Evolutionary | The performance of evolutionary algorithm is similar to learning-based systems. They achieve better results only if the changes are gradual and not abrupt. |

| Wireless systems | These are new generation systems in which the data about the vehicular traffic are aggregated through wireless communications and then the signal timings are calculated according to the received data. This approach helps to adapt to recurring as well as non-recurring traffic and thus helps in improving the waiting time and the queue length |

It is pretty much evident that dynamic traffic signal controls are capable of addressing the demands of varying traffic conditions. However, there is still a lot of scope for improvement. This can be achieved by exploring various possible avenues. Among all, wireless VANETs are emerging as an effective solution for intelligent transportation systems of which traffic signal control is a part. VANETs can provide real-time information of the volatile traffic and are thus perceived to enable signal control systems to operate with greater efficiency. In addition, sharing traffic signal and operations data with other systems will improve overall transportation system performance. Few proposed works discussed in this literature [MAS 12], which was discussed in section 7.3, show how the use of vehicular networks can improve the traffic flow at the intersection. However, as with any other technique to implement adaptive traffic lights using VANETs, the issues pertaining to it have to be addressed.

[AAS 01] AASHTO, Standard Specification for Structural Supports for Highway Sign, Luminaries and Traffic Signals, American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials, 2001.

[ABD 03] ABDULHAI B., PRINGLE R., KARAKOULAS G.J., “Reinforcement learning for true adaptive traffic signal control”, Journal of Transportation Engineering, vol. 129, pp. 278, 2003.

[ALI 06] ALIPOUR M.A., JALILI S., “Urban signal control using intelligent agents”, Applied Artificial Intelligence 7th International FLINS Conference, World Scientific Publishing Company, pp. 811–816, 2006.

[ANT 05] ANTUNOVIĆ M., GLAVAŠ H., “Fuzzy logic approach for traffic signals control of an isolated intersection”, Skup o prometnim sustavima s međunarodnim sudjelovanjem AUTOMATIZACIJA U PROMETU 2005.

[BRA 08] BRAUN R., KEMPER C., WEICHENMEIER F., “TRAVOLUTION: Adaptive urban traffic signal control with an evolutionary algorithm”, Proceedings of the 4th International Symposium “Networks for Mobility”, Stuttgart, September 25th and 26, 2008.

[BRU 94] BRUNO G., IMPROTA G., BIELLI M., et al., “Urban traffic control: current methodologies”, Artificial Intelligence Applications to Traffic Engineering, pp. 69–93, 1994.

[DOA 09] DOAN Q.C., BERRADIA T., MOUZNA J., “Vehicle speed and volume measurement using vehicle-to-infrastructure communication”, WSEAS Transactions on Information Science and Applications, vol. 6, no. 9, pp. 1468–1477, 2009.

[DUA 10] DUAN H., LI Z., ZHANG Y., “Multiobjective reinforcement learning for traffic signal control using vehicular Ad Hoc network”, EURASIP Journal on Advances in Signal Processing, vol. 2010, pp 7–17, 2010.

[ELT 10] El-TANTAWY S., ABDULHAI B., “An agent-based learning towards decentralized and coordinated traffic signal control”, Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), 2010 13th International IEEE Conference on, IEEE, pp. 665–670, 2010.

[FAH 06] FAHMY M.M.M., “An adaptive traffic signaling for roundabout with four approach intersections based on fuzzy logic”, Journal of Computing and Information Technology, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 33–45, 2006.

[GOR 96] GORDON R.L., TIGHE W., UNITED STATES FEDERAL HIGHWAY ADMINISTRATION. OFFICE OF OPERATIONS, UNITED STATES FEDERAL HIGHWAY ADMINISTRATION, OFFICE OF TRANSPORTATION MANAGEMENT, DUNN ENGINEERING ASSOCIATES, AND ITS SIEMENS, Traffic control systems handbook, Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration, Office of Technology Applications, 1996.

[GRA 07] GRADINESCU V., GORGORIN C., DIACONESCU R., et al., “Adaptive traffic lights using car-to-car communication”, IEEE 65th Vehicular Technology Conference 2007 (VTC2007-Spring), IEEE, pp. 21–25, 2007.

[GRE 07] GREGOIRE P.L., DESJARDINS C., LAUMÔNIER J., et al., “Urban traffic control based on learning agents”, IEEE Intelligent Transportation Systems Conference, 2007 (ITSC 07), IEEE, pp. 916–921, 2007.

[HEN 98] HENSON M.A., “Nonlinear model predictive control: current status and future directions”, Computers and Chemical Engineering, vol. 23, no. 2, pp. 187–202, 1998.

[HOS 10] HOSSEIN P.N., SHAHROKH V., MAZIAR N., “Vehicular ad hoc networks”, EURASIP Journal on Advances in Signal Processing, vol. 2010, pp. 1–2, 2010.

[HOU 01] HOU T.C., TSAI T.J., “A access-based clustering protocol for multihop wireless ad hoc networks”, IEEE Journal on Selected Areas in Communications, vol. 19, no. 7, pp. 1201–1210, 2001.

[HUA 04] HUANG Q., MILLER R., “Reliable wireless traffic signal protocols for smart intersections”, ITS America Annual Meeting, San Antonio, Texas, 2–4 May, 2004.

[JER 07] JERBI M., SENOUCI S.M., RASHEED T., et al., “An infrastructure-free traffic information system for vehicular networks”, IEEE 66th Vehicular Technology Conference 2007 (VTC-07), IEEE, pp. 2086–2090, 2007.

[KHA 05] KHALID M., LIANG S.C., YUSOF R., “Control of a complex traffic junction using fuzzy inference”, Control Conference 2004 5th Asian, vol. 3, IEEE, pp. 1544–1551, 2005.

[KOO 04] KOOPMAN A., VREEKEN J., VEENEN J., et al., Intelligent traffic light control, Technical report UU-CS-2004-029, Utrecht University, 2004.

[KUT 06] KUTIL M., HANZÁLEK Z., CERVIN A., “Balancing the waiting times in a simple traffic intersection model”, Proceedings of 11th IFAC Symposium on Control in Transportation Systems 2006, Citeseer, Netherlands, 29–31 August 2006.

[LEV 98] LEVINSON D.M., “Speed and delay on signalized arterials”, Journal of Transportation Engineering, vol. 124, no. 3, pp. 258–263, 1998.

[LIU 07] LIU Z., “A survey of intelligence methods in urban traffic signal control”, IJCSNS, vol. 7, no. 7, pp. 105–112, 2007.

[MAS 11] MASLEKAR N., BOUSSEDJRA M., MOUZNA J., et al., “C-DRIVE: clustering based on direction in vehicular environment”, Proceedings of IEEE International Conference of New Technologies, Mobility and Security (NTMS), Paris, 7–10 February 2011.

[MAS 12] MASLEKAR N., BOUSSEDJRA M., MOUZNA J., et al., “CATS: an adaptive traffic signal system based on car-to-car communication”, Journal of Network and Computer Applications, 2012.

[MIZ 08] MIZUNO K., FUKUI Y., NISHIHARA S., “Urban traffic signal control based on distributed constraint satisfaction”, Proceedings of the 41st Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, IEEE, pp. 65–70, 2008.

[NAD 04] NADEEM T., DASHTINEZHAD S., LIAO C., et al., “TrafficView: traffic data dissemination using car-to-car communication”, ACM SIGMOBILE Mobile Computing and Communications Review, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 6–19, 2004.

[PRO 10] PROTHMANN H., ROCHNER F., TOMFORDE S., et al., “Organic control of traffic lights”, Autonomic and Trusted Computing, Springer, vol. 1, pp. 219–233, 2010.

[PRU 05] PRUD’HOMME R., “The current EU transport policy in perspective”, Conference on European Transport Policy in the European Parliament, European Commission, Brussels, p. 3, 2005.

[SCH 05] SCHRANK D.L., LOMAX T.J., TEXAS TRANSPORTATION INSTITUTE, The 2005 Urban Mobility Report, Texas Transportation Institute, Texas A & M University, 2005.

[SKA 04] SKABARDONIS A., “Traffic signal control systems”, Assessing the Benefits and Costs of ITS, Springer, vol. 1, pp. 131–144, 2004.

[SUT 98] SUTTON R.S., BARTO A.G., Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction, The MIT press, 1998.

[VAN 06] VAN KATWIJK R.T., DE SCHUTTER B., HELLENDOORN J., “Traffic adaptive control of a single intersection: a taxonomy of approaches”, Proceedings of the 11th IFAC Symposium on Control in Transportation Systems, Elsevier, IFAC Papers Online, pp. 227–232, 2006.

[WEN 08] WEN W., “A dynamic and automatic traffic light control expert system for solving the road congestion problem”, Expert Systems with Applications, vol. 34, no. 4, pp. 2370–2381, 2008.

[ZHA 05] ZHANG L., LI H., PREVEDOUROS P.D., “Signal control for oversaturated intersections using fuzzy logic”, TRB 2005 Annual Meeting CD-ROM, Washington DC, 9–13 January, 2005.

[ZHO 10] ZHOU B., CAO J., ZENG X., et al., “Adaptive traffic light control in wireless sensor network-based intelligent transportation system”, Vehicular Technology Conference Fall (VTC 2010-Fall), 2010 IEEE 72nd, IEEE, pp. 1–5, 2010.