6

BLUE CANOES MAKE DEBUT

Southeast Alaskans dreamt for years of a highway that could connect their island-bound towns with the outside world. Statehood became the catalyst to make it happen. Gov. William A. Egan appointed Richard A. Downing as the state’s first commissioner of Public Works, and Downing made creating a passenger-car ferry system a priority.

In January 1963, Southeasterners saw their dream become a reality with the maiden voyage of the M/V Malaspina. When the first of three planned ferries sailed into Ketchikan, now the home base for the Alaska Marine Highway System, the 3,000 townspeople rejoiced as they watched the sleek blue and white vessel with eight-stars-of gold painted on its smokestack ease into the terminal for her first tie-up at the dock, according to the Ketchikan Daily News. They now could travel along the 450-mile length of Southeastern Alaska’s panhandle from Ketchikan to Haines, at the head of Lynn Canal.

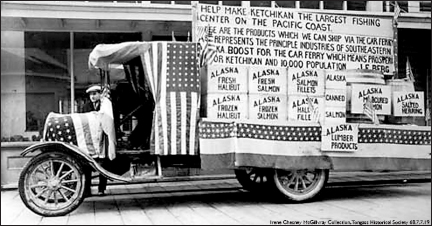

Carl Cordell’s decorated truck in the Fourth of July parade shows the serious side of Ketchikan’s wish for a ferry system in 1917.

The M/V Chilkoot cruised by Columbia Glacier in the 1950s.

The genesis of the modern ferry system began in 1949 when Haines residents Steve Homer and Ray Gelotte founded the Chilkoot Motorship Lines. The men purchased and converted a surplus World War II LCT-Mark VI landing craft from the U.S. Navy and christened it the M/V Chilkoot. The vessel had a day lounge, bathrooms, a galley and crew quarters.

The 100-foot-long ship with a crew of seven could carry 20 passengers, 13 cars and travel at about 9 knots – a little more than 10 mph. It made weekly trips between its home base at Tee Harbor, 18 miles north of Juneau, to Haines-Port Chilkoot and Skagway, according to Stan Cohen, author of a book featuring the history of the Alaska Marine Highway System titled Highway on the Sea. This service connected Alaska’s capital with the Alaska-Canada Highway, built in 1942, at Haines Junction, 150 miles north of Haines.

The territorial government bought the company in 1951 and placed it under the Territorial Board of Road Commissioners. Six years later, the board replaced it with the M/V Chilkat, which stayed in service until 1988.

The Chilkat was a tad bit smaller, at 99 feet long, but could carry 59 passengers and 15 vehicles. Built by J.M. Martinac Shipbuilding Co. of Tacoma, Wash., it had a distinct bow ramp that allowed it to load from a beach as well as a dock. The new ship was painted with the blue and gold that now is synonymous with the ferries in the fleet and soon was dubbed the “Blue Canoe.”

Alaskans could not add any more ships to help move passengers, however, as they were not allowed to float bonds for a ferry system or any other economic project under territorial government. And the federal government was hard pressed to spend unnecessary funds on “Seward’s Icebox.”

The M/V Chilkat, which began serving Southeast Alaska with ferry service in 1957, is seen in this photo getting work done at Seward Marine Ways dry dock in Ketchikan.

The Alaska Steamship Co. had filled the void for more than 50 years as it carried freight and passengers between Seattle and Southeast. But it then dropped its passenger schedule in 1952. The new Alaska-Canada Highway and the proliferation of airliners cut into the steamship company’s business so much that regularly scheduled sailings no longer proved profitable. The last steamer sailed away from Southeast Alaska in 1954.

Five years later, statehood brought renewed vigor for a ferry system. The first state Legislature set the stage for creating a department of public works. The second session in 1960 brought a proposal to provide funding to build a marine highway. Voters approved Bond Proposition No. 2 for $23 million – $182.5 million in 2015 dollars – to create a ferry system throughout Southeast and Southcentral Alaska.

Public Works Commissioner Downing consulted with experts in both Canada and the United States, which resulted in the “Study and Report on the Alaska Ferry System of February 1961,” according to a newspaper article in the Juneau Empire. Downing acquired as much information as possible to make sure the ferry system would be practical, economical and of the most benefit to the people it would serve.

Controversy surrounded the idea of the ferry system from the beginning. Perhaps because much of Alaska’s population did not live in Southeast and they didn’t understand the importance of connecting the communities on the Panhandle. Some may have thought the price too high to pay.

Others saw it as a crazy idea that never would pay for itself. The author of this Alaska history series, Laurel Downing Bill, remembers some people calling the proposed ferry system “Downing’s Folly” at the time – commissioner Downing was her father.

But after Downing analyzed all the information needed to proceed, he and his team drew up plans for four new vessels – each to carry 500 passengers, 105 vehicles, 44 staterooms and many reclining chairs in the fore and aft lounges for napping – along with new docks throughout the proposed system.

Alaska state ferry M/V Malaspina first arrived in Ketchikan on Jan. 23, 1963.

Building began immediately on terminal facilities at the mainline ports of Haines, Skagway, Juneau, Sitka, Petersburg, Wrangell, Ketchikan and Prince Rupert, British Columbia, which became known as “the little Canadian town that the Alaska ferries turned into a city,” according to newspaper reports. Canadian officials improved and straightened the road from Prince Rupert to Canada Highway 16 to accommodate increased traffic expected as a result of the new ferry system.

Gov. Egan’s wife, Neva, christened the 352-foot-long M/V Malaspina on June 8, 1962. Designed by Philip Spaulding, it was built for $4 million at Puget Sound Bridge and Dry Dock in Seattle. When the ship slid down rails into the water, Gov. Egan said it was “perhaps the most important and permanent achievement for Alaska since statehood.”

The vessel, which cruised at 18 knots, arrived in Ketchikan on Jan. 23, 1963. Three days later, it docked in Wrangell for the first time. The Wrangell Sentinel covered the fanfare with a flourish.

“Three long blasts from the Wrangell Lumber Co.’s whistle at 6:45 yesterday morning welcomed the M/V Malaspina to this lumber capital of Alaska,” the Sentinel reported.

Admiral B.E. Lewellen, head of the Marine Transportation Division, was aboard for the maiden voyage.

“She’s running nicely,” Lewellen told a reporter. “We’re taking it easy, ironing out the kinks, and everything seems to be highly successful.”

Gov. Egan also was aboard and greeted the official boarding delegation, as did Downing and his wife, Hazel, who were enjoying the inaugural run.

“The Commissioner was duly proud of the new vessel,” a reporter noted.

Downing’s wife, Hazel, christened the second ship – M/V Taku – that went into service in April that year. Admiral Lewellen’s wife christened the third ship, M/V Matanuska, which followed in June. The ships, all named after glaciers, became known as the Alaska Marine Highway System.

“These vessels follow the same sea route traveled by thousands of sourdough gold seekers through the heavily forested islands of Alaska’s mountainous Panhandle,” a travel brochure proclaimed. “Visitors pass scores of dazzling glaciers flanked by magnificent fjords. Busy fishing ships of every size and description share this tireless view.”

During its first year of service, the marine highway extended its reach from Ketchikan to Petersburg, Sitka, Skagway, Wrangell and Prince Rupert, B.C. The fleet moved more than 15,000 vehicles and 80,000 passengers.

The ocean-certified M/V Tustumena followed in 1964. The 240-foot-long ship, which became known as the “Trusty Tusty,” brought the marine highway to Kodiak. The ship could carry 200 passengers and 40 vehicles along its route, which included stops at Anchorage, Seward and Homer, with occasional “flag stops” at Seldovia.

Tusty’s design included a loading elevator on the stern so vehicles and cargo could be offloaded at any dock without a loading ramp, according to a SitNews article by Dave Kiffer titled “The Grand Ships of the Alaska Marine Highway System,” dated July 8, 2006. Unfortunately, the ship suffered significant rolling when traveling the Gulf of Alaska, so it had to be modified five years later. It was lengthened by 56 feet, which alleviated the rolling problem.

The Chilkat moved to Prince William Sound, where it began service between Valdez and Cordova – then Valdez to Whittier. In 1969, M/V E.L. Bartlett joined the Chilkat in Southcentral Alaska and soon established a marine highway between the Kenai Peninsula and the Kodiak area. The 193-foot ferry, which traveled at 12 knots, could carry 190 passengers and 41 vehicles. Named for much-loved politician Edward Lewis “Bob” Bartlett, who died in December 1968, this was the first Alaska ferry specifically built for the marine highway that was not named for a glacier.

“… families with their cars can travel the fabled Inside Passage all the way from Vancouver Island through the scenic Alaska Panhandle to Haines, where a 158-mile highway will take them to the Alaska Highway and into the great heartland of the 49th state,” reported the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner on March 17, 1966, as it announced the link up of Canada’s M/V Queen of Prince Rupert in British Columbia with the Alaska ferries.

When a rockslide took out a section of the Alaska Highway in 1967, and the Queen of Prince Rupert ran aground, the transfer ability of passengers using the ferry service between Alaska, Canada and Washington became restricted.

Then-Gov. Walter J. Hickel ordered the Alaska Marine Highway System to send a ship south to Seattle as he worked with the federal government to reclassify the route from “outside waters” to “inside waters,” as none of the state ferries had the necessary ocean-going certifications to travel on outside waters. The feds agreed to do so, which left the system with a significantly longer route and no new ships to serve it.

In an effort to get a new ship into service quickly, marine highway officials purchased a 1-year-old vessel named the Stena Britannica and rechristened it the M/V Wickersham, after a much-respected early judge, political leader and advocate for Alaska statehood. The 363-foot ocean-going ship, which carried 1,300 passengers, was never reflagged as an American ship, however.

The sturdy little auto and passenger ship M/V Chilkat was sent to the historic ports of Valdez and Cordova after larger ferries went into service in Southeast Alaska during 1963.

Author Laurel Downing Bill remembers her mother, Hazel Downing, telling her stories of how she and Gov. William Egan’s wife, Neva, spent several days painting the inside of the ship as it made is way from Southeast to its new home in Prince William Sound. The women wanted to spruce it up and make it shine for the people of Southcentral Alaska.

The Chilkat provided water-and-mountain-locked Cordova with the city’s only surface link to Valdez and the Richardson Highway. It began with three weekly trips during the summer months and two trips monthly during the winter. The 87-mile ferry trip between the two ports took 7-1/2 hours.

After the Good Friday 1964 earthquake, the ferry was shifted to the Valdez-Whittier run. And then, in 1969, it returned to Southeast for the Juneau to Hoonah run. In 1977, it was put on the Ketchikan-Hollis-Metlakatla route.

In 1988, Alaska’s oldest ferry was sold and - up into the early 2000s – it was still part of the regional fishing industry.

From 1968 to 1972, the M/V Wickersham could only operate between U.S. ports if it stopped in Prince Rupert, B.C. Its bow loading system limited its Alaska service to Ketchikan, Juneau, Sitka and Haines, too.

The deep draft of the Wickersham also made it impossible to traverse narrow, shallow areas like Peril Strait near Sitka, which led to some adventurous stormy trips in the open ocean on the outside of Baranof Island and elsewhere during the winters.

While the Wickersham was not a luxurious ship, it was definitely fancier than the other, more utilitarian members of the fleet.

The Wickersham’s commercial operation between two American ports of call was in violation of the Jones Act. Enacted in the 1920s to protect U.S. shipbuilders, the act prohibits foreign vessels from traveling between American ports unless there is an intermediate stop in a foreign country. The state attempted to get a waiver, but federal officials would not agree.

So while the Wickersham could pick up passengers in Seattle, and deliver them to Alaska by stopping in Canada on the way, it could not move passengers within Alaska. The ship also had not been built with Alaska ports in mind, so she could not physically dock at several places.

The 1,000-passenger M/V Columbia, specifically built for the marine highway system, replaced the Wickersham in 1974. The 418-foot ship cost $22 million and became the largest ferry in the fleet.

Alaska’s marine highway proved so successful, that both the Matanuska and Malaspina had to be stretched by 56 feet at their midsections to accommodate more passengers and vehicles, which left the Taku as the only ship in Southeast that could serve the smaller communities.

The fleet also added the M/V LeConte in 1974, and her sister ship, M/V Aurora, in 1978. These 235-foot Wisconsin-built vessels each carried 250 passengers and 34 vehicles and were the last new ships of the feet for the next 20 years. They completed the initial construction phase of the marine highway.

A few more ferries were added in later years, and the Alaska Marine Highway System now extends 3,500 miles. It has a network of ferries that stop at 35 ports from Bellingham, Wash., to Southeast to Prince William Sound to Kodiak to the Aleutians.

The system also proved economical for the state, according to a report written by Dr. George W. Rogers for the University of Alaska in 1970.

“The annual net public cost of operating the Alaska Marine Highway System for the five-year period (1965 to 1969) was $2.9 million, as compared with $58.3 million for all roads in the state,” Rogers reported. “… This resulted in per capita annual cost of providing highway systems to the public (directly served) of $31.76 for the Marine Highway against $260.94 for the Land Highway.”

Commissioner Downing, who died in 1988, would be pleased to know that the Blue Canoes sailing Alaska’s saltwater highways not only fulfilled his desire for economy and efficiency, but also have led to economic and travel opportunities that continue to expand the horizons of once-isolated Alaska communities.

Alaska Marine Highway System 1963

When the Alaska Marine Highway System debuted in 1963, its three ferries – M/V Matanuska, M/V Taku and M/V Malaspina – opened a new world of exploration to the American driving public. Prior to ferry service Alaska’s panhandle region, which features countless islands, massive glaciers and deep-forested fjords, only could be viewed by air or steamship.

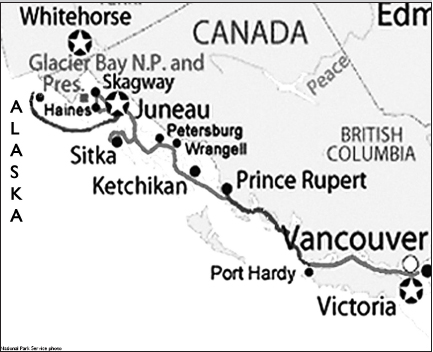

The south terminal of the 450-mile route was Prince Rupert, British Columbia. From there, it connected to the seven Alaska towns of Ketchikan, Wrangell, Petersburg, Sitka, Juneau, Haines and Skagway. Passengers could connect to Alaska’s road system once they reached Haines.

The Marine Highway not only brought tourists to this once-isolated section of Alaska, but it brought many opportunities, as well.

Ketchikan

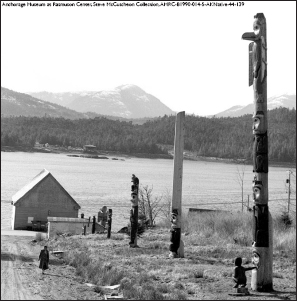

The Alaska Marine Highway System’s first northbound stop was Ketchikan, known as “Salmon Capital of the World.” It also was home for the world’s largest collection of totem poles and the site of Alaska’s first pulp mill.

Wrangell

Wrangell, the third-oldest town in Alaska, boasted salmon, crab and shrimp canneries during the 1960s. It featured the busiest sawmills in the state, too.

Petersburg

One of the most picturesque places in Southeast Alaska, Petersburg was known for its white halibut fishing fleet, manned by the descendants of Scandinavian fishermen who first settled the city. It showcased the world-record 126-pound king salmon in the 1960s.

Sitka

The influence of old Czarist Russia permeates Sitka, Alaska’s first capital after it became part of the United States in 1867. Old St. Michael’s Russian Orthodox Cathedral, built in the 1840s, housed religious treasures. It burned down in 1966 and later was rebuilt.

Juneau

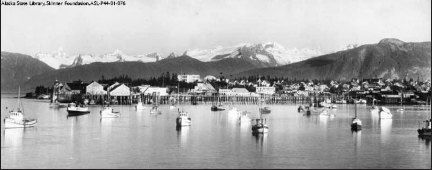

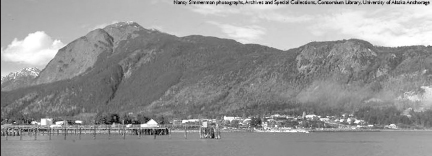

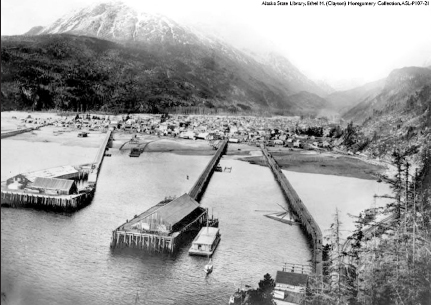

Proclaimed by many as “The Nation’s Most Scenic Capital,” Juneau, shown above, sits near Mendenhall Glacier – the most photographed glacier in the world. It is home to the first major gold rush north after rich deposits were found in Silver Bow Basin in 1880.

Haines

Haines and Port Chilkoot, twin cities of the ferry route, sit on the coastal end of the Haines Highway that connects to the Alaska Highway near Whitehorse, B.C. Visitors during the 1960s enjoyed “Totem Village,” where they watched authentic Chilkat Indian dancers, observed totem pole carvers and wandered through a recreated tribal house.

Skagway

The farthest north stop on the Alaska Marine Highway System was Skagway, gateway to the Klondike gold fields of 1898. A narrow-gauge railway connects to Whitehorse, B.C., and the Yukon Territory. Skagway embraces the gold-rush era with its amazing museum and “Days of ‘98” shows.