13

SEWARD BURNS

“An isolated ghost town populated by the living” was the Seattle Times’ view of Seward following the Good Friday earthquake of 1964. Just a day before it had shared the news that the town on Resurrection Bay had been named an All-America City by the National Civic League.

Standard Oil Co. seaman Ted Pederson was on the Seward dock checking and adjusting valves between his ship and the bulk storage tanks when he felt the second-largest earthquake in recorded human history hit at 5:36 p.m. on March 27.

“Earthquake!” he shouted as he ran toward his ship, Alaska Standard. Within 30 seconds of the first violent shake, he saw the oil tanker buck and then slam into the dock, he later told interviewer Genie Chance.

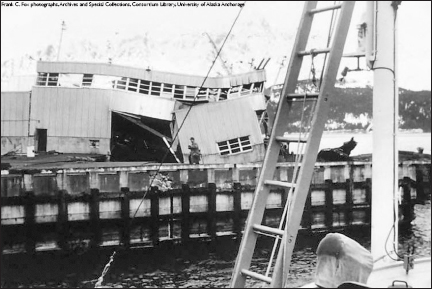

He continued up the dock toward the beach – then saw all the oil pipelines leading from the beach to the dock break in one place. Geysers of gasoline shot skyward. Pilings then flew upward, a 200-foot warehouse sank and the Alaska Standard pitched and dropped 30 feet to hit land.

Pedersen said he flew into the water when the dock collapsed. As he struggled to stay afloat in the turbulence, he saw a giant wave filled with debris heading toward him. He then fell unconscious when something hit him on the back of his head.

The Good Friday earthquake of 1964 and the tidal waves that followed destroyed most of the buildings and docks in Seward.

The massive wave tossed him onto the catwalk of his ship, eight feet above the deck. When he came to, he found his fellow crewmates fighting flames aboard the tanker and he had a broken leg.

Dean Smith was working in the cabin of a gantry crane about 50 feet above the Alaska Railroad dock when the quake struck. He later reported the top of the crane flipped back and forth “like a long whip,” and when the wheels came off the tracks, his crane began “walking around like some stiff-legged spider.” Smith quickly scrambled down and began leaping over cracks appearing in the pavement on the dock that were a foot wide and “getting bigger all the time.”

As he and a fellow worker made their way to higher ground, they saw East Point Cannery float on top of a huge wave and then sink into Resurrection Bay. Smith told Chance they also saw the wave pick up many vehicles parked at the dock, and then a burst of flames shot 200 feet in the air from the Standard Oil storage tanks.

Moments before the explosion, Val Anderson had just walked into his house on Sixth Avenue after working a full day as a longshoreman on the Standard Oil dock. His wife, Jean, was in the bathroom and his three children – Susie, 9, Sharon, 6, and Eric, 4 – were sitting on the living room floor watching “Puppet Spaceship XL,” their favorite television show.

“I’m so thankful for that,” Anderson said in an interview for Aunt Phil’s Trunk in 2013. On most days, his children would have been outdoors playing somewhere in the neighborhood. “Other parents didn’t find their kids until the next day.”

Within seconds he heard an overwhelming rumble. Then he felt the house shake so hard that the hanging light in the living room almost hit him in his head. The kitchen refrigerator lurched sideways.

About 20 seconds after the first jolt, Anderson heard a giant “whoosh!” and felt heat as a Standard Oil tank exploded and flames shot more than 100 feet straight up – higher than the tree tops out his living room window.

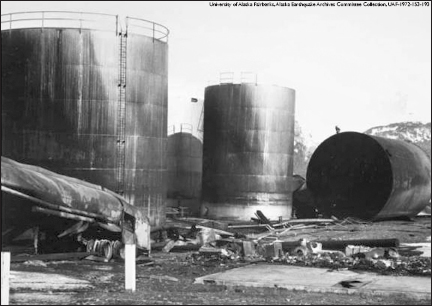

Oil tanks near the docks in Seward exploded and burned during the 1964 Good Friday earthquake.

He had one thought: Get the children and his wife out of the house immediately as it was only a few blocks from what he felt would become a massive fire. He knew there were more tanks and hundreds of 10-gallon cases of aviation gas in that warehouse on the dock.

“Get in the car!” he shouted to the children and then rushed to the bathroom to get his wife. He found her hanging onto the sink and grabbed her. The two managed to get back down the hall to the front door. But then Jean fell down the steps.

Anderson stumbled down to her and lifted her back onto her feet. She took a few steps, then fell again and slid under the car.

The longshoreman pulled her up once more, pushed her into their sedan and took off, leaving the front door of their home wide open.

“We just had to get away from the fire,” he said.

As the family drove toward the first bridge out of town, Anderson glanced toward the boat harbor. He saw a large power barge heaved in the air on a 15- or 20-foot wave above the breakwater. His wife saw water splashing over the railroad tracks.

When they reached the first of the three bridges leading out of Seward, they found a crack had split the road about two feet before the deck of the bridge. Anderson then knew they would not be escaping out of town, as the other bridges probably had suffered similar damage.

So he doubled back and made his way to higher ground at Forest Acres, along with many other Seward residents, about two miles from his house.

Others fleeing the fire drove down Third Avenue only to find that a wave had deposited railroad cars, parts of houses and other debris on the road. Some came across Al Wisdom using a bulldozer to try and clear the road. About 20 minutes later another tidal wave swept over Seward and no one ever saw Wisdom again.

“It was quite a night,” Anderson said. “We listened to the roar of Standard Oil tanks exploding, and at times tidal waves moving in, and watching the great, red glare of the fire lighting the sky and mountainsides.”

Tidal waves carried fires from ruptured fuel tanks across Seward.

Fire and tidal waves devastated the little town of Seward on Resurrection Bay.

The refuges also felt strong aftershocks about every hour, which kept nerves on edge.

“Around midnight, someone came along for a head count,” Anderson said, adding that the final death count was 12 in Seward.

“Whenever someone saw a kid, they’d pick him up and take him to safety,” he said. “So many parents didn’t know for a long time if their kids were gone or safe.”

Anderson never thought his house would survive the blazing inferno that appeared to be engulfing the town. The next morning, however, he found his home in tact when he drove into Seward. But he also found much of the town destroyed.

Waves from various sources had created havoc on the small town, including an underwater landslide beneath the waterfront; the sloshing effect in Resurrection Bay; and displacement water from the earthquake fracturing the floor beneath Prince William Sound.

Burning oil covered most of the water surface. Flames from that oil spread to many parts of Seward as the waves swept further inland to the Texaco Petroleum tank farm, starting another fire. Water and burning fuel surged across the railroad tracks and into the city’s north end, crushing dozens of homes, house trailers, waterfront stores and the radio station. Flames set debris ablaze and swept up against the foot of the mountains behind the city. As it crossed the highway leading to higher ground, a giant wave overtook several people who were fleeing in their vehicles and moved a 60-ton locomotive six blocks.

But it could have been worse, according to Richard Lemke, who visited Seward shortly after the earthquake and wrote a report for the U.S. Geological Survey.

“Had not a gentle wind been blowing eastward across the bay, the entire town probably would have burned,” he surmised.

The earthquake, tidal waves and fires left Seward helpless. The disaster wiped out the town’s harbor, utilities, road and rail lines, and communications. The airport remained the only useable facility, and it would play a critical role linking the battered town to civilization for many days.

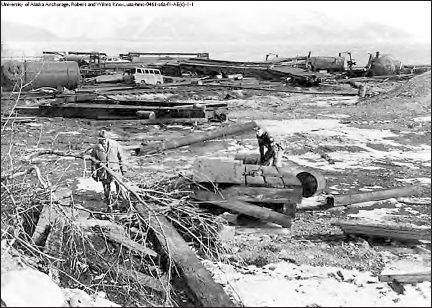

U.S. military troops helped Sewardites look for the missing and clear debris.

Twenty-one U.S. Army soldiers were in Seward the day the earthquake struck. They were preparing to open the Army Recreation Center during the All-America City celebration slated for the following weekend.

Most, in the dining hall at the time of the shaker, escaped to higher ground, grabbing children from nearby houses as they ran. Once they recovered from the shock of the event, several soldiers made their way to the Seward hospital to help out with casualties.

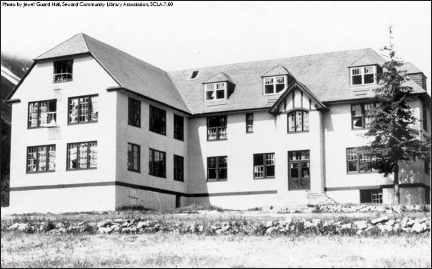

The three cooks in the group went to the Jesse Lee Home orphanage and got the kitchen working on Army field ranges. They manned the kitchen all night and into Saturday afternoon, feeding the residents of the home and any other hungry Seward residents, according to a military document titled “Operation Helping Hand.”

The soldiers worked with the police and townspeople as they searched through the wreckage of the devastated city looking for the injured and bodies.

By 10 a.m. Saturday, the military was flying more than 150 military troops to Seward – including 36 Alaska Army National Guardsmen who had been in Anchorage for a two-week tour of active duty at Fort Richardson. They brought a radio-teletype with them, which finally gave Seward communications with the outside world. It remained the only link until late on March 31, when two telephone lines went into operation.

One of the first messages sent out let the state Civil Defense Headquarters in Anchorage know that Seward badly needed utility experts to help reestablish water, sewer and electricity.

A demolitions expert had been sent along to Seward, also. City leaders had hoped he would be able to blow the fire out of the burning oil tanks, but that proved impossible. However, he was able to knock down some dangerously damaged buildings, blast pits for latrines and did a few other jobs that needed explosives.

The military brought a water purification unit, too, which was set up at a small lake near the city. Six water trailers then were placed around town for public use. The unit produced 10,000 gallons of water that Saturday and continued at peak capacity until not needed on April 9.

Seward’s water supply became polluted with garbage and sewage following the earthquake and tidal waves. The U.S. military brought a water purification unit into town and set up water trailers.

Alaska National Guard cooks made meals for the residents of Seward at the Jesse Lee Home orphanage, which sat on high ground and was safe from the tsunamis.

Cooks from the Alaska National Guard took over cooking at the Jesse Lee Home, and the Army cooks then opened a mess hall at the high school to feed those left in Seward. Food was gathered from damaged stores and homes. This community kitchen prepared, on average, 800 meals a day for citizens and volunteers. Another military field kitchen fed the soldiers who were helping out.

The Alaskan Air Command delivered nearly 200,000 pounds of relief cargo to Seward in the first few days following the earthquake. Members of the Civil Air Patrol also airlifted food, medical supplies, fuel, equipment and many passengers to Seward and other towns along the Kenai Peninsula. Those pilots helped evacuate people from Seward, Hope and Portage, too.

In an effort to keep information flowing following the destruction to Seward’s Radio Station KIHB, Army personnel and city officials mimeographed a daily bulletin. That newssheet helped keep Seward’s citizens abreast of what was happening in their town.

When a Seattle newspaper heard about the Seward radio station’s problem, it published a story that led to another radio station donating a transmitter. The transmitter was shipped free via Northwest Orient Airlines to Anchorage, where it transferred to an Air National Guard C-123 that flew it to Seward.

Armed Forces Radio Service loaned a few more bits of equipment, and soon military technicians had KIHB back on the air three days after it went silent. It then served as a Civil Defense communications link.

Even though Seward, the All-America City with a promising future, was blackened by those raging fires, battered by the earthquake, inundated by tidal waves and lost about 95 percent of its industry, the rush of aid from the military and others helped its residents soldier on in the face of adversity.

When Seward city leaders met with Alaska’s U.S. Sen. E.L. “Bob” Bartlett on Saturday, they told him that the city needed federal money to help rebuild the city.

“We need a grant … with no red tape,” they told him, because if the federal government went the route of giving Seward a loan, the townspeople would have to vote a bond issue to pay it back.

“We couldn’t float a bond issue on peanut butter in this town right now,” Seward City Manager James W. Harrison said.

After the meeting, Bartlett flew to Washington, D.C., for a Monday meeting to give a disaster report to government officials.

“Well, we’ve no place else to go but up,” was the opinion of most of the people of Seward. In a delayed presentation of the first All-America City award three months after the earthquake, Stanley Gordon, editor of Look magazine, who presented the award, said he had been deeply depressed by the earthquake reports at first, for it seemed that Seward was completely destroyed.

“‘What will we do about the All-America City award?’ I asked myself,” Gordon told Seward’s citizens. “But, before I could dwell upon the disaster, my mind was relieved by a telegram from the valiant city: ‘Doing OK – everything considered!’”

Like the mythical Phoenix, Seward rose again. From the ashes of fire and devastation of flood, in 1965 the city again won an All-America City award, as did Anchorage and Valdez – this time given for a resurrected Seward.

The townspeople built new and completely modern docks, improved the small boat harbor and constructed a marine way and canneries. They’d built new homes and businesses and put in new sewer and water lines. And they promoted Seward’s Silver Salmon Derby to perhaps the biggest single sporting event in Alaska – one that attracts thousands of visitors to the city on Resurrection Bay to this day.

As the years march forward, Seward will never forget those who were lost and the courage of those who remained. The Seward City Council established the first Sunday after Easter as “Seward Memorial Thanksgiving Day.”

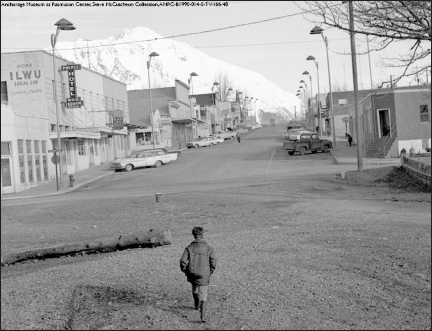

The townspeople of Seward rebuilt their city better than before the Good Friday earthquake of March 27, 1964, as seen in this photo taken in 1968.