17

TIDAL WAVES OVERTAKE KODIAK

Sixteen minutes before the Good Friday earthquake, the Rev. Donald Bullock watched as carpenter Louis Horn selected two small eye bolts to hang a new cross from the ceiling above the altar in the sanctuary of Kodiak’s St. James the Fisherman Episcopal Church. The men shared their conversation in the church, which sat atop the hill above the harbor, for an Anchorage Daily Times story two weeks after the massive shaker.

“Do you think these will hold it, Louis?” the minister asked.

“Sure, Father,” Horn replied.

“What if we have an earthquake?” Bullock asked, and then chuckled.

“Even in an earthquake,” the carpenter assured him.

Eyewitnesses said they heard a rumbling sound five seconds before feeling the first tremor. At 5:36 p.m. on March 27, 1964, the ground slowly began to shake. Within a minute of the initial tremor, the shaking grew more intense.

Chuck Powell, chairman of the Kodiak Island Borough Assembly, raced out of an office on the second floor of the bank building. He hurried downstairs and out into the street. The shaking became so severe that most people had to hang on to something to stay standing, he remembered.

“Power lines snapped, poles whipped back and forth, and buildings swayed with cracking noises,” he later told interviewer Genie Chance.

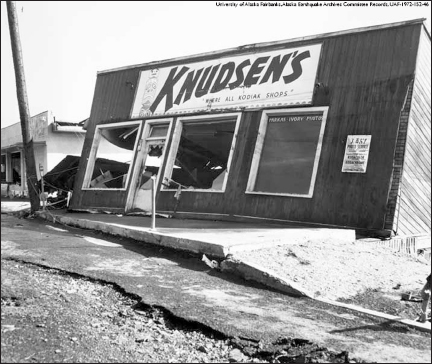

The 1964 earthquake and tidal waves knocked Knudsen’s store in downtown Kodiak right off its foundation.

“The shaking was violent for about one minute and trailed off for about two to three minutes,” according to Kodiak city engineer Jim Barr. The city’s electrical power went out at 5:40 p.m.

Kodiak Island Borough tax assessor Howard Fremlin said the hard jolt and shaking sent everyone in the waterfront Elk’s Club toward the front door. The floor moving up and down in waves made walking difficult.

“When you took a step, your foot was still on the floor instead of up in the air,” Fremlin told Chance. “We fell and stumbled, waded through the broken glass and falling bottles, and finally made it outside.”

Once out in the street, he saw ground waves, utility poles “fanning in the breeze,” telephone and power lines snapping and glass store fronts “popping out.”

Fremlin said he noticed wooden frame buildings “rolling and swaying.” But none collapsed.

He jumped in his car and quickly drove to his house on a bluff overlooking the small boat harbor, about half a mile from the Elk’s Club. From this vantage point, he and his wife watched as water rose to the top of the pilings. It came up so fast that most boats were not able to cut loose in time to escape as part of the breakwater broke away and swept the dock and boats into town.

The water then receded rapidly, leaving the small boat harbor almost dry.

“It was just sucking right out of the harbor,” Fremlin later recalled.

Pharmacist Kelly Boyd, who ran out of the downtown drug store as merchandise crashed to the floor around him, said sirens began to wail about 30 minutes after the quake to warn of tidal wave danger.

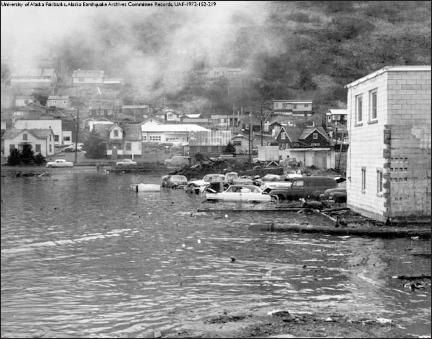

Witnesses on Pillar Mountain watched as a tidal wave swept into Kodiak following the 9.2 temblor that struck Southcentral Alaska on March 27, 1964.

The Fremlins packed their car and drove through the business district en route to Pillar Mountain. They noticed several people milling about as though nothing had happened.

But most of Kodiak’s residents instinctively knew that they had to head to higher ground. They believed a tidal wave would strike at any minute. And they were right.

Rev. Bullock’s family joined a stream of vehicles heading up Pillar Mountain.

They stopped about a mile up and settled in to wait. That’s when they heard an announcement come over a shortwave radio that Kodiak was sinking into the sea.

At 6:30 p.m. a wave surged in like a fast-rising tide and struck with such force it tossed buildings and boats around – making a complete mess of the waterfront.

Mrs. Fremlin described it as a “big, foaming wave” before it struck the outlying islands. It then swamped Mission Road and surged around the shoreline into the small boat harbor where it “foamed and boiled and bubbled.”

“It all happened so fast that very few of the boats were able to get out of the harbor,” said assemblyman Powell, who was watching the devastation from a safe distance on a hill. “I’ve shot the Snake River in a sea skiff, and I wouldn’t have wanted to be out there (in the channel).”

He saw the water carry away boats, a plane, buildings and the channel’s buoy marker.

“And you know what the anchor is on those (buoy markers),” Powell said. “And they made about four or five passes up and down the channel.”

This wave, which crested at 23.5 feet 15 minutes later, knocked the King Crab Cannery into the water. While floating intact, it crashed into the bulkhead. The Donnelly Atchison store also broke loose and picked up a hangar with a Grumman Goose in it – both were swept away as the water withdrew.

Another eyewitness reported a massive wave rushed in at 8:30 p.m., crested at 24.5 feet, and took out the pile driver. The sound of the waves was “half roaring and half hissing,” he recalled.

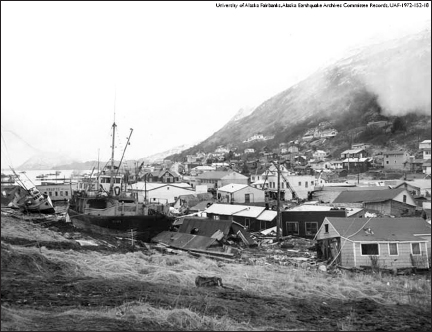

This aerial photograph shows the devastation caused by several tidal waves that swamped Kodiak following the record-strength earthquake on Good Friday 1964.

The water again withdrew from the shore.

Powell said the first two waves “loosened things,” but caused little damage to downtown Kodiak. It was the third wave at 11 p.m., reaching an elevation of 25.5 feet, and the fourth wave, topping off at 26.5 feet that arrived at 12:30 a.m., which dealt the most destruction.

Mrs. Fremlin said the water withdrew between Kodiak and Near Island after each wave and stayed out for a long time. Then it returned – each time traveling faster and farther inland.

The tidal waves killed 14 and caused around $24 million in damage. They destroyed more than 100 homes, as well as the telephone utility, movie theater, grocery store, dry goods store, bars, fish canneries, boats and docks.

The Armed Forces Radio at the Kodiak Naval Station fell off the air after the first wave struck as water inundated that building and the power house, leaving the station without heat or power for five days. The waves finally subsided enough by 7 a.m. on Saturday that workmen could begin clearing the road to the nearby U.S. Navy base, which also sustained heavy damages and dropped 5.5 feet.

This view of the wreckage suffered by Kodiak’s residents includes smashed buildings and boats all across the downtown area.

Tidal waves carried many boats in Kodiak’s fishing fleet into various sections of the mainland.

As residents made their way back into town, they found everything topsy-turvy. A home filled with mud sat in the middle of the main street. Cars had been dragged out to sea, while boats had landed all over town. One boat, the Selief, made the news after State Trooper Don Church, attempting to locate all the missing fishing boats, called out on his radio.

“Selief, Selief, where are you?”

“It looks as though I’m in the back of the Kodiak schoolhouse, five blocks from the shoreline,” came skipper Bill Cuthbert’s reply.

The U.S. Army and Air Force arrived to help the Naval base and residents of Kodiak get back on their feet. They provided equipment and technicians to furnish the town with a temporary telephone system and installed telephones in businesses and strategic spots like the fire department and civil defense headquarters. Since poles had been toppled, heavy field wire stretched across the ground connecting the system.

A 150-man Seabee disaster team, equipped with tools, rations and cold-weather clothing, arrived the day after the quake and tsunamis, according to military reports. They immediately started repairing the power plant, roads and river crossings. Welders and pipefitters repaired the city’s main crab freezing plant. Crane operators cleared demolished and damaged buildings.

One building would not need to be razed, however. The Episcopal Church up on the hill made it through the earthquake and tsunamis just fine.

Rev. Bullock’s wife, Evelyn, wrote about the family’s experience through the whole ordeal in an article published in the Spokane Daily Chronicle a few weeks after the disaster. She said the quake had “shaken, cut, dropped, heaved and twisted the earth in many places, but in the little church overlooking Kodiak harbor, it had failed to shake loose Father Bullock’s new cross.”

Other structures did need replacing, though. But rebuilding in the same location was not feasible since the center of town, along the northeast end of Kodiak Island, had sunk nearly six feet and flooded with seawater every day at high tide.

Townspeople, business owners and the city of Kodiak obtained low-interest loans through the federal Urban Renewal program to replace houses, fishing boats, commercial buildings and the boat harbor.

They cleared the debris out of Old Kodiak, then flattened hills and excavated gravel from the base of Pillar Mountain to fill the low-lying center of town. Their original town – a mix of small houses and stores, cottonwood trees and winding gravel roads – turned into a modern city filled with commercial buildings and wide paved streets.

Hundreds of fishing boats and numerous fish processing plants now make Kodiak one of the most productive commercial fishing ports in the nation.