18

VILLAGES NEAR KODIAK IN RUINS

The ancient Alutiiq village of Afognak, located on an island about three miles north of Kodiak Island, suffered greatly from the devastating Good Friday earthquake and tidal waves that followed. Once it had been a large village, with more than 1,000 inhabitants. But by March 27, 1964, only 190 remained, according to a U.S. Census Bureau report.

The villagers made their living from the sea, just as their ancestors before them, and lived in small frame homes that stretched four miles along the lowlands facing the sea. The village also boasted a community hall, store, schoolhouse and lumber mill.

Enola Mullen, owner of the village store, and her husband were in the store when they felt a “long, steady shaking.” It knocked merchandise from shelves and made cars parked outside rock back and forth at 5:36 p.m.

Alfred Nelson, sitting in a rocking chair in his home, thought at first that his children were rocking his chair. Then he saw the ceiling light swaying and a bucket half-full of water sloshing.

“That’s when I knew it was an earthquake,” he later told interviewer Genie Chance. “I was wondering when it was going to quit.”

He then heard a report on his shortwave radio that Seward had been wiped out. Nelson looked out in the bay and saw the water higher than normal, and told his wife to put the children in the car and head up the mountain. He then followed in his truck, picking up several other people along the way.

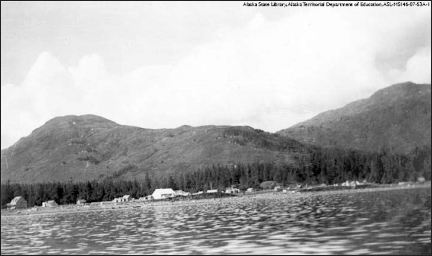

Following the Great Earthquake of 1964, a series of high waves inundated Afognak Village, seen here in 1934. The damage was so extensive that the village had to relocate.

Peggy Needham, one of three schoolteachers, heard a radio report around 6:30 p.m. from the Kodiak Naval Station warning of an approaching tidal wave 15 feet high and advising people to go to higher ground.

She and other villagers tossed blankets, food and warm clothes into their cars and trucks and raced up the mountains behind the village. The first wave caught several people in the lower part of the village as they were trying to run toward higher ground. They managed to wade through the waist-high water to safety.

Needham and her neighbors watched as monstrous waves surged over their homes, smashing them like kindling wood. They saw several homes and the community hall sucked back into the sea when the water withdrew in a mad whirlpool of debris. Soon other buildings were swept off their foundations and moved inland; automobiles and trucks washed into small lakes behind the village; and ice in the lakes carried out to sea.

“They weren’t standing waves – not a wall of water – as you’d expect,” said Needham as she described the waves to Chance. “But rather the water rushed in like a high tide, only 10 times faster and a good 15 to 20 feet higher than normal.”

All night long the ocean surged and receded. The villagers huddled in the snow and cold while tremors sporadically shook the earth beneath them. When they finally came down the mountain, they found 23 of their 38 homes were destroyed.

The Mullens discovered the waves had deposited their store one-third mile inland. Two of its exterior walls had been demolished and the remaining portion of the building was lodged among some trees. They salvaged what merchandise they could and gave it to the villagers who had lost everything.

One woman told Chance that the waves had lifted her house and its foundation right out of the ground and washed it about one-quarter mile inland. Although the floors were damaged by water and mud, none of the windows had broken and the knickknacks still stood on the windowsills where she had placed them before the quake.

The villagers of Afognak rebuilt their community and named it Port Lions, seen here in 1968.

Two days after the tsunamis, a radio report warned that another 90-foot wave was to be expected at any moment. The villagers again fled to the safety of the mountain. They returned to the village during daylight hours, Needham said, but continued to sleep on high ground for several nights.

No one at Afognak died in the earthquake and tsunamis that followed. But skipper John “Sut” Larsen, returning from Kodiak on board his fishing boat Spruce Cape, must have run into trouble on the sea. His body later was found, ironically, at Spruce Cape, the landmark after which his boat was named. Harry Nielson, another Afognak villager, also died on that boat along with Theodore “Ted” Panamarioff of Ouzinkie.

It was decided that rebuilding the village at that same location was not feasible. Not only had the majority of the homes been destroyed, but the tectonic subsidence at Afognak had brought saltwater into the wells.

A new site was selected on Kizhuyak Bay on Kodiak Island. The site choice wasn’t popular with some villagers, so they instead chose to move to Kodiak, other towns in Alaska or the Lower 48.

The philanthropic Kodiak Island Lions Club helped those who wanted to establish their new village on Kodiak Island. And soon a new identity began to develop, according to the village website – that of the people of Port Lions. There the villagers continue to pass on to new generations their ancestors’ traditions and culture.

Old Harbor

Another community, Old Harbor, sits on the southeast coast of Kodiak Island about 70 miles southwest of the city of Kodiak. It has been inhabited for around 2,000 years by Alutiiq people. Most residents, like the Shugaks, were living a subsistence lifestyle when the Good Friday earthquake hit.

Young Tobias Shugak was lying on a bed in his family’s home at 5:36 p.m. His sister stood nearby holding a baby sister. At first he thought his sister was shaking the bed.

“But it got harder, and my sister said ‘earthquake!’ and we ran outside,” he told interviewer Genie Chance.

The children said the “huge snake” made all the buildings in the village weave back and forth as the ground moved in waves. They added that the dock pilings began “twirling in the air” and then the water “went way out – farther than light tide.”

Villagers fled to the mountain, even though rocks, dirt and snow were sliding down toward the village.

Janet Tunohun remembered her father saying a tidal wave was headed their way. The family immediately joined other villagers in climbing to higher ground.

“And a wind came up,” Tunohun said, adding she saw the “big, ugly wave come in and hit the houses.”

Residents of the village of Old Harbor gathered for evacuation at the school, one of two buildings left standing following the earthquake and tidal waves of March 27, 1964.

The schoolhouse and church, seen in this photo of Old Harbor taken in the 1950s, were the only buildings left intact following tidal waves on March 27, 1964.

Some of the houses broke apart, and others just floated away. She remembered a lamp burned brightly inside one house as it floated out to sea like a boat.

“Some houses went around in a circle and landed on the land again,” Shugak recalled.

His father and another man were aboard the fishing boat Alexander in Old Harbor bay when the quake struck. Shugak told Chance that an incoming wave swept the boat into the village, “almost to the schoolhouse,” and then receding water carried it seaward again until it became stranded on the dry bottom of the bay. The men jumped overboard and ran to the mountainside and joined the other villagers.

In the bright moonlight, the villagers watched as the water came and went all night and destroyed all the homes in their village. Only the school and church were left standing. One witness, who entered the church the next day, reported that the high water mark inside the missionary’s house was six inches from the ceiling. The waves had destroyed the chapel, along with all records, books and the organ.

The villagers rebuilt their community in the same location, and incorporated their city in 1966.

Ouzinkie

Tidal waves also inundated Ouzinkie, located on the west coast of Spruce Island about 12 miles north of the city of Kodiak, following the Good Friday earthquake. Originally established in the mid-1800s as a retirement community for the Russian American Co., the Russians referred to the settlement in 1849 as “Uzenkiy,” which means “village of Russians and Creoles.” Other sources say, however, it means “rather narrow.”

By the time of the 1964 earthquake, the village existed for the fishing industry and its more than 150 residents were a mixture of Russian and Alutiiq people.

Some who went through the quake described seeing ground waves as long as 30 feet cross the village when it hit at 5:36 p.m. on March 27.

Earl and Merrle Carpenter had arrived in the village the year before to serve as cannery storekeeper and postmaster for the Ouzinkie Packing Co. cannery. They later said in an article for the Alaska Historical Society that the earthquake did not cause much structural damage.

Merrle Carpenter quickly started snapping photographs to show her boss what had happened. She did not know at the time that she was capturing photos of the bay going dry.

The villagers told her and her husband to get to high ground because all the water that had left the bay was going to all come back.

“And it’s going to come back fast,” the villagers said.

The Carpenters joined the rest of the village climbing up Mount Herman above the cannery store. They remembered everyone was concerned for those still out on fishing boats who had not yet returned to Kodiak Island. They could hear them on the radio, calling for help – then the radio went dead when a huge wave covered the store.

Records later showed that five men aboard the F/V Spruce Cape, heading toward Ouzinkie, lost their lives to the tsunamis that followed the quake.

After a series of tsunamis washed through the cannery, the Carpenters made their way down to the severely damaged store and salvaged some supplies to help feed the villagers. Although the labels had been washed off the tin cans, the food inside was fine.

The couple later managed to save the cannery safe, as well, and dried out $4,000 in waterlogged bills on top of their stove.

They found the back half of the store had washed out to sea along with most of the cannery building. The livelihood of most of those in Ouzinkie washed away, too.

Massive tsunamis destroyed the Ouzinkie Packing Co. on March 27, 1964,

The U.S. Postal Service commended the Carpenters, who left the village in May 1964, for “the unselfish devotion to the public service that was so amply demonstrated by postal people during the disastrous earthquake.”

They also received a personal note of thanks from Alaska’s U.S. Sen. E.L. “Bob” Bartlett.

Following the disaster, Columbia Ward bought the remains of the store and rebuilt it and the dock, but not the cannery. Then in the late 1960s, the Ouzinkie Seafoods cannery was built. That operation sold out to Glacier Bay, but it burned down in 1976, shortly after the sale. No canneries have operated there since.

Kaguyak

Another community, Kaguyak, located at the head of Kaguyak Bay on the southeast coast of Kodiak Island, was a happy Alutiiq-Russian village with about 20 residents on the afternoon of March 27, 1964. The Good Friday earthquake and resulting tsunamis changed it forever.

Renee Alexanderoff, 22 and pregnant at the time of the earthquake, told Genie Chance that her husband, Chief Simeon “Simmie” Alexanderoff, helped her and their three children escape up the mountain following the initial earthquake. He and three other fishermen – Zaedar Anakenty, Victor Melovedoff and Max Shelikoff – then returned to the village to help rescue Donald Wyatt, a geologist from Los Angeles, and his wife, Joyce, who were camping outside the village.

The men loaded them and clothing into a dory and then pushed it over a small hill between the village and the lake. The group almost made it across the lake to safety when a huge wave burst across the shore, through the village, over the hill and across the lake.

The water swamped the dory and three of the men lost their lives. Alexandroff was last seen clinging to the dory. His body was never found. They later found Anakenty’s body on the beach and Wyatt floating in the lake.

Kaguyak sat on a strip of land by a lake, as seen in this photograph taken prior to the earthquake and tsunamis of March 1964.

Walter Meloeoveoff, Renee’s 61-year-old father, told Chance they were getting dinner when they heard a “kind of whistle.” He said he’d had a premonition earlier that day that something might happen.

“Then come the earthquake,” he said.

The family ran outdoors as the shaking got worse. They looked at the bay and noticed the tide had receded an unusually long distance.

They knew a wave would be coming and fled with several villagers toward the mountain. Meloeoveoff stopped to assist an elderly woman, recuperating from illness, so he trailed the others. He looked back and saw a huge wave heading toward them.

“Oh, boy, that big swell was coming about 20 feet behind us, just rolling in, and all the woods and ice in it,” he recalled. “We just made it.”

The water receded and the “big bay” went totally dry.

Another wave, bigger than the first, swept in and washed away the buildings and killed the men attempting to cross the lake in the dory.

The villagers stayed on the mountaintop where the temperature registered 18 degrees that clear, still night. The next morning, they were evacuated.

Dories carried them through choppy, debris-filled waters to the large crabber Fern anchored offshore in low tide.

Once aboard the ship, the villagers learned that skippers Fred Ogden and Wayne Mathewson had been just off the southern coast of Kodiak Island when the quake struck. The men said that the boat jerked and bounced as if striking bottom, but they just thought they were in rough waters.

It wasn’t until they heard a radio report about the earthquake and tsunamis that they realized what had happened. They then dumped their boatload of crab overboard so they could maneuver the boat better and settled in for a long night.

At daybreak, they motored toward nearby Kaguyak and Old Harbor to see if anyone needed assistance. When they arrived at Kaguyak, they found no houses left. So they anchored and rescued the villagers.

The people of Kaguyak relocated to other villages, including Old Harbor and Akhiok, seen here, following the 1964 earthquake.

They loaded about 100 people on board the vessel and then headed for Kodiak, making a few stops en route to help villagers salvage art treasures and icons from their church that were floating in the ocean.

The Fern finally made it to Kodiak. But while unloading the passengers and gear, a high tide came in. Soon people were wading in waist-high water on the dock as they retrieved bundles of clothing and the paintings from the Russian Orthodox Church that had been rescued on the way.

Kaguyak never was rebuilt. Some of the villagers settled in Akhiok, some relocated to Old Harbor.